Abstract

Background

Catechins are the main polyphenol compounds in tea (Camellia sinensis). To understand the relationship between gene expression and product accumulation, the levels of catechins and relative expressions of key genes in tea leaves of different developmental stages were analyzed.

Results

The amounts of catechins differed significantly in leaves of different stages, except for gallocatechin gallate. Close correlations between the expression of synthesis genes and the accumulation of catechins were identified. Correlation analysis showed that the expressions of chalcone synthase 1, chalcone synthase 3, anthocyanidin reductase 1, anthocyanidin reductase 2 and leucoanthocyanidin reductase genes were significantly and positively correlated with total catechin contents, suggesting their expression may largely affect total catechin accumulation. Anthocyanidin synthase was significantly correlated with catechin. While both ANRs and LAR were significantly and positively correlated with the contents of (−)-epigallocatechin gallate and (−)-epicatechin gallate.

Conclusion

Our results suggest synergistic changes between the expression of synthetic genes and the accumulation of catechins. Based on our findings, anthocyanidin synthase may regulate earlier steps in the conversion of catechin, while the anthocyanidin reductase and leucoanthocyanidin reductase genes may both play important roles in the biosynthesis of galloylated catechins.

Keywords: Camellia sinensis, Catechins, Chalcone synthase, Anthocyanidin synthase, Anthocyanidin reductase, Leucoanthocyanidin reductase

Background

Polyphenolic compounds, which are widely distributed in plants, contribute to color (Tsuda et al. 2004) and flavor (Lea 1992) and are involved in pigment biosynthesis (Kurauchi et al. 2011), plant disease defense (Matern and Kneusel 1988) and damage caused by abiotic stress (Solovchenko and Schmitz-Eiberger 2003). Notably, polyphenols are responsible for the protective effects of plants against a variety of human diseases including cancer (Thomasset et al. 2007). Tea, which contains abundant polyphenols (Mukhtar and Ahmad 2000; Higdon and Frei 2003), is one of the most popular beverages in the world. Among the polyphenols, catechins are the major components, occupying more than 10 % of dry tea leaves (Wei et al. 2011). Catechins in tea can be separated into epicatechins (GTE) and GTE epimers. GTE include (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), (−)-epicatechin gallate (ECG), (−)-epigallocatechin (EGC) and (−)-epicatechin (EC); while major GTE epimers include (−)-gallocatechin gallate (GCG), (−)-gallocatechin (GC) and (−)-catechin (C). The content and function vary with the individual catechin (Henning et al. 2003; Bigelow and Cardelli 2006).

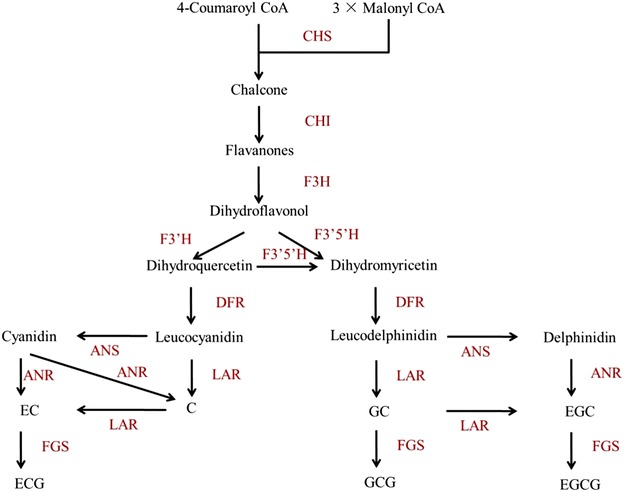

Catechins are biosynthesized by different branches of the phenylpropanoid biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 1) (Wang et al. 2012). Chalcone synthesis is the first step in the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway, and the chalcone synthase gene (CHS) encodes the key enzyme for this step. A strong correlation exists between CHS gene expression and flavonoid content in many plants (Kamiishi et al. 2012; Morita et al. 2012; Dare et al. 2013). Sequencing of CHS in several plants shows that normally more than one copy is present (Jiang et al. 2006; She et al. 2013). Three highly similar copies of CHS in Camellia sinensis (CHS1, CHS2 and CHS3) have been cloned, and their expression pattern mirrors the pattern of catechin accumulation in the leaves and stems (Takeuchi et al. 1994). Using reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and HPLC, Eungwanichayapant and Popluechai (2009) demonstrated that the accumulation of CHS3 mRNA is higher in the shoots, where most catechins are more prominent. Expressed sequence tag analysis yielded similar results in regards to CHS1 and CHS2 (Park et al. 2004). Mamati et al. (2006) suggested that the expression profile of CHS genes in tea differs across the development stages of tea leaves. However, it is still not clear which CHS gene plays a more important role in affecting catechin biosynthesis. In addition to CHS, anthocyanidin synthase (ANS), anthocyanidin reductase (ANR) and leucoanthocyanidin reductase (LAR) are downstream genes in the polyphenol biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 1). ANS catalyzes the conversion of leucoanthocyanidins to anthocyanidins (Wilmouth et al. 2002). ANR is involved in the production of the flavan-3-ol monomers (such as epicatechin from anthocyanidin) (Bogs et al. 2005). While LAR catalyzes the conversion of leucocyanidin, leucodelphinidin or leucopelargonidin to the corresponding 2,3-trans-flavan-3-ol (Tanner et al. 2003). These genes might play important roles in determining the compositions of catechins (Saito et al. 1999; Punyasin et al. 2004; Xie et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2012) (Fig. 1). However, to what extent of these genes affect catechin compositions still remains elusive.

Fig. 1.

The proposed catechin biosynthetic pathway in Camellia sinensis. CHS chalcone synthase (EC 2.3.1.74); CHI chalcone isomerase (EC 5.5.1.6); F3H flavanone 3-hydroxylase (EC 1.14.11.9); F3′5′H flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase (EC 1.14.13.88); F3′H flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase (EC 1.14.13.21); FLS flavonol synthase (EC 1.14.11.23); DFR dihydroflavanol 4-reductase (EC 1.1.1.219); ANS anthocyanidin synthase (EC 1.14.11.19); ANR anthocyanidin reductase (EC 1.3.1.77); LAR leucocyanidin reductase (EC 1.17.1.3); FGS flavan-3-ol gallate synthase (EC number not assigned)

In this study, quantitative real time PCR (qPCR) was performed to determine the relative expression of genes involved in catechin biosynthesis, including CHS1, CHS2, CHS3, ANS, ANR1, ANR2 and LAR in C. sinensis leaves at different developmental stages. Furthermore, the concentration of individual catechins was analyzed using HPLC. The aim of this study was to provide increased understanding of the regulation of catechin synthesis in the tea leaves by investigating the relationship among the accumulation of tea catechins, gene expression levels and leaf developmental stages.

Methods

Plant materials

Clonal tea (C. sinensis var. sinensis cultivar Longjing 43) was grown at the tea garden of the National Tea Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Hangzhou, China. Leaf samples were collected in March 2013, when the forth leaves reached near final size. The buds, first leaves, second leaves, third leaves and completely mature leaves were collected from tea cultivar Longjing43 for subsequently analysis. Buds, the first, second and third leaves were defined as new shoots. Part of tea samples were microwaved at high power for 1 min and then dried in an oven at 60 °C for 24 h for catechin analysis (Gulati et al. 2003). The rest collected samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70 °C for RNA isolation.

Catechin extraction and HPLC analysis

Catechins were extracted as described by Wang et al. (2014). Tea sample (0.2 g, dry weight) was extracted with 5 ml 70 % methanol in a water bath at 70 °C for 10 min with intermittent shaking. The supernatant was placed in a 10 ml volumetric flask, and the extraction step was repeated to reach the final volume of 10 ml. The extracts were filtered through a 0.45-μm Millipore filter before the injection was made. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

The extracts were analyzed using an Agilent 1100 HPLC system. Separations were carried out using a Phenomenex RP-MAX 4 μm 250 mm × 4.6 mm i.d. C12 reverse phase column maintained at 40 °C, eluted at 1 ml min−1 with a 60 min gradient of 4–25 % gradient of acetonitrile in water containing 1 % formic acid and monitored at 280 nm (Del Rio et al. 2004).

The standard chemicals, including catechin (C), epicatchin (EC), gallocatechin (GC), epigallocatechin (EGC), Epicatechin gallate (ECG), gallocatechin gallate (GCG), epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Quantitative real time PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA from the samples was extracted using the SV Total RNA Isolation System (Promega Corporation, USA) as described in the technical manual. The integrity and quality were checked by determining absorbance using the NanoDrop spectrophotometer ND-1000 (NanoDrop Technologies Inc., USA). First strand cDNA was synthesized from 320 ng of total RNA and oligo (dT) primer using the PrimeScript II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (TAKARA, Japan) as described in the product manual. The cDNA was used immediately or stored at −20 °C until used for the PCR test.

Primers for PCR (Table 1) were designed using Primer 3.0 according to the sequences of CHS1 (Accession No. D26593), CHS2 (Accession no. D26594), CHS3 (Accession no. D26595), ANS (Accession no. GAAC01051116), ANR1 (Accession no. GU944768), ANR2 (Accession no. JN024667) and LAR (Accession no. EF205148). The PCR analysis was carried out using the ABI PRISM7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System as described in the SYBRPremix Ex Taq™ (perfect real time) (TAKARA, Japan) kit manual. 18S rRNA from C. sinensis was taken as an internal control gene. Three replications were taken for each experiment.

Table 1.

Primers of catechin biosynthetic genes for real-time PCR analysis in Camellia sinensis

| Gene | Accession no. | Primer sequence 5′−3′ |

|---|---|---|

| CHS1 | D26593 | Forward: CAGAGCACGTACCCGGATTATTAC |

| Reverse: GGTACTTCAACCACAACCATGTCC | ||

| CHS2 | D26594 | Forward: CATTACTAACAGCGAGCATAAAACG |

| Reverse: TAGTTTTGGGACTTCAACAACCAC | ||

| CHS3 | D26595 | Forward: CCTCTTCCTAGCTAGCACATACCA |

| Reverse: TGCTCGCTATTAGTAATCCGAAAGT | ||

| ANS | GAAC01051116 | Forward: TGGGAAGACTATTTCTTCCACCTT |

| Reverse: TTCTAGTCGGCCTTCTTCTAGTCC | ||

| ANR1 | GU944768 | Forward: CCTTCTAGCACTAAAGGGTTCAGG |

| Reverse: TGACTACTCCTTGAATTGCTGGTT | ||

| ANR2 | JN024667 | Forward: TCACAGGGAATGAATTCCTCATAG |

| Reverse: GGAACATTGTACTGGGGGTATCTT | ||

| LAR | EF205148 | Forward: TTTTGTTGCAGGCTCTGATATAGG |

| Reverse: ATTATATTCACTGCTGCTGCTGCT | ||

| 18S rRNA | AB120309.1 | Forward: TCTCAACCATAAACGATGCCGACCAG |

| Reverse: TTTCAGCCTTGCGACCATACTCCC |

Statistical analysis

Results were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and statistical differences were examined by the Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test. Differences at p < 0.05 were considered to be significant. Correlations analysis was determined using SAS 9.0 software, and charts were plotted using Sigma Plot 12 software.

Results

Catechin analysis by HPLC

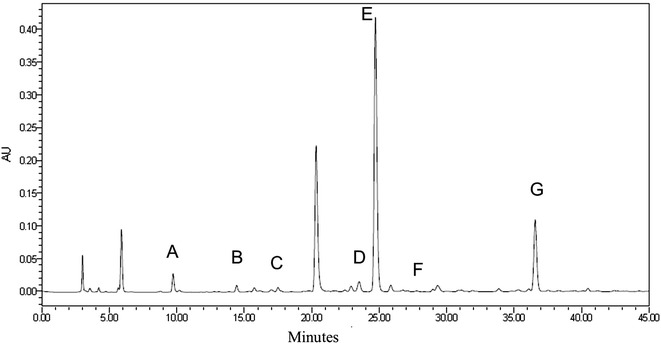

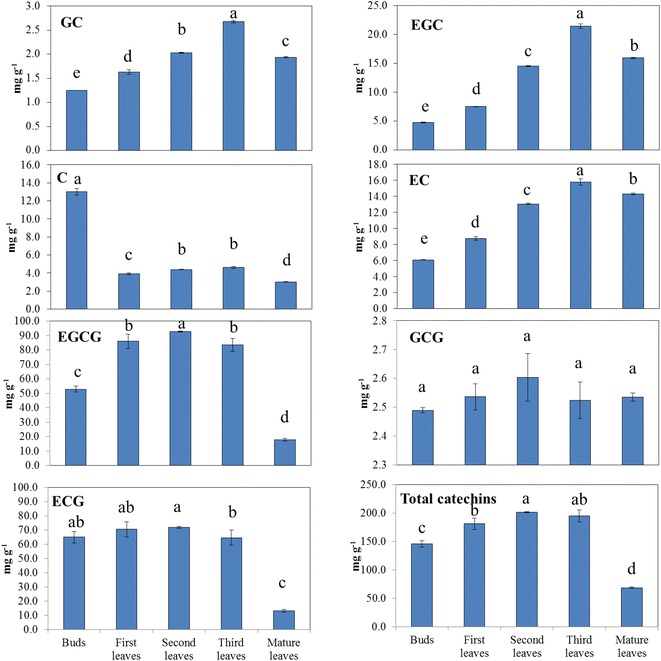

Good separation was achieved with peaks identified as the 7 individual tea catechins (Fig. 2). The order of peaks was GC, EGC, C, EC, EGCG, GCG and ECG. The catechin contents in different leaf stages are shown in Fig. 3. It could be found that EGCG and ECG had the highest concentrations, totally occupied about 80 % of total catechin contents. While the contents of GC and GCG were relatively low, ranging from 1.25 to 2.68 and 2.49 to 2.60 mg/g respectively. The amounts of all catechins differed significantly at different developmental stages, with the exception of GCG, which remained relatively constant at all stages (p = 0.180). The second leaves contained the highest total catechin content, and the individual catechins, with the exception of GCG, were most concentrated in the new shoots. The mature leaves had the lowest C, ECG, EGCG and total catechins. Among the new shoot samples, a general increase of the non-galloylated catechins was observed with increasing age of the leaves, with the third leaves having the highest concentration. The pattern of galloylated catechins in the new shoots was similar, except that the highest concentration appeared in the second leaves. According to the biosynthetic pathways of flavan-3-ols in C. sinensis leaves (Ashihara et al. 2010), galloylated catechins are synthesized through non-galloylated catechins with the help of flavan-3-ol gallate synthase (FGS). Hence, we deduce that the distinction found in this experiment may be caused by a variation of FGS activities. It was also worth noting that the highest C content was observed in the buds, with a sharp decrease at the rest stages, which was consistent with our previous findings (Wei et al. 2011).

Fig. 2.

Chromatogram of the catechin components in tea. Results from a representative HPLC experiment are shown. The individual peaks represent A (gallocatechin; GC), B (epicatechin gallate; EGC), C (catechin; C), D (epicatechin; EC), E (epigallocatedchin gallate; EGCG), F (gallocatechin gallate; GCG), and G (epicatechin gallate; ECG)

Fig. 3.

The changes of catechin fractions and total catechins in tea leaves of different stages. Lower case letters on the upper right corner: Statistically significant difference as determined by Fisher’s least significant difference test. Same letters in each column mean there is no significant difference in the same catechin in different developmental stage leaves, otherwise, significantly different (p = 0.05)

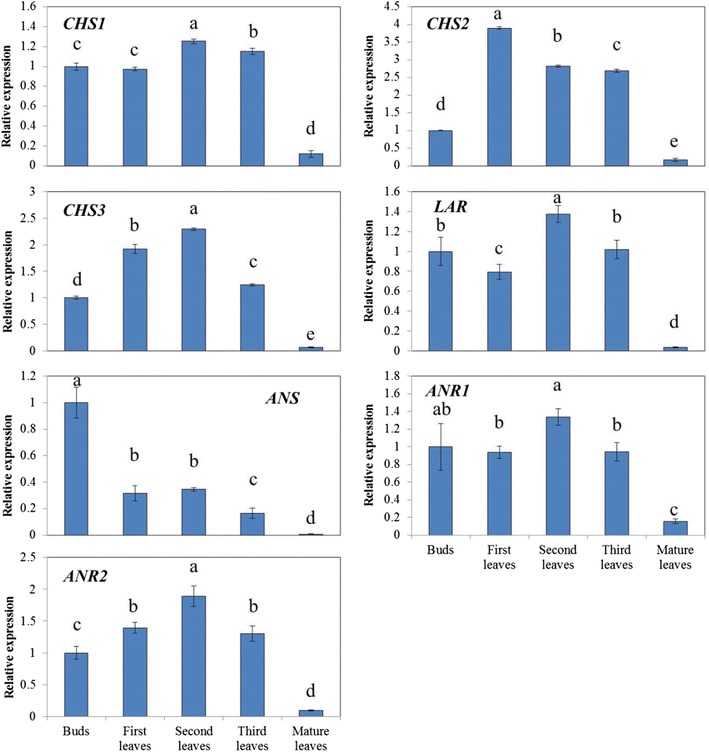

Expressions of catechin synthetic genes

To investigate the developmental expression patterns of catechin synthetic genes, CHS1, CHS2, CHS3, LAR, ANS, ANR1 and ANR2 in C. sinensis, qPCR was performed using gene-specific primers to measure expression levels (Fig. 4). cDNA samples prepared from leaves at different developmental stages were used as template. Transcript levels of all of these genes were at least 5-fold higher in young leaves than in mature leaves. Furthermore, the relative expression levels differed at different developmental stages. The expression of CHS2 showed the largest variation in the 3 CHS genes, ranging from 0.172 in the mature leaves to 3.901 in the first leaves. Whereas CHS1 and CHS3 exhibited relatively less variations, ranging from 0.122 to 1.254 and 0.066 to 2.293 respectively. Moreover, the expressions of CHS1 and CHS3 peaked at the second leaf stage, which was different from that of CHS2.

Fig. 4.

Relative expressions of catechin synthetic pathway genes in tea leaves of different stages. The relative expressions of the CHS, ANS, ANR and LAR genes at the bud stage, the new shoot stage (1st, 2nd and 3rd leaves), and the mature leaves stage were shown. Expression of each gene was standardized to the expression of 18s rRNA and normalized to 1 at the bud stage. Results represent averages ± SD of three plants tested in triplicate

The expression of LAR fluctuated dramatically during the developmental stage. Down by 20 % at the first leaf stage, LAR showed a sharp rise afterward, reaching its peak at the second leaf stage. Then it was followed by a significant fall in the third leaves. The expression of ANR1 and ANR2 showed a similar pattern to LAR during the developmental stages. Both of them reached their peaks at the second leaf stage while ANR2 showed larger variation. It is also worth noting that the expression pattern of ANS was largely different from the other genes. ANS showed a general downward trend during the developmental stage, with its peak at the bud stage and the bottom at the mature leaf stage.

Correlation analysis of catechin contents and relative gene expressions

The correlation between catechin contents and relative gene expressions was analyzed in Table 2. Correlation analysis showed that CHS1 was highly significantly and positively correlated with ECG and total catechin contents, and significantly correlated with EGCG, indicating it might play a more important role in influencing catechin accumulation than CHS2 and CHS3. Furthermore, both ANR1 and ANR2 were significantly correlated with total catechins, EGCG and ECG, suggesting ANRs are essential for EGCG and ECG biosynthesis. On the other hand, ANS showed no significant correlation with EGCG and ECG, but was significantly and positively correlated with C, indicating its potential role in C biosynthesis. It is also worth noting that LAR was not significantly correlated with C and GC, but showed positive relationship with ECG and total catechins, suggesting the possible conversion of C to EC in tea plants.

Table 2.

The correlation between catechin contents and relative gene expressions

| GC | EGC | C | EC | EGCG | GCG | ECG | Total catechins | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHS1 | 0.134 | −0.069 | 0.265 | −0.174 | 0.916* | 0.224 | 0.968** | 0.964** |

| CHS2 | 0.222 | −0.009 | −0.312 | −0.029 | 0.919* | 0.378 | 0.775 | 0.854 |

| CHS3 | 0.036 | −0.150 | −0.087 | −0.158 | 0.937* | 0.579 | 0.871 | 0.896* |

| LAR | 0.081 | −0.082 | 0.309 | −0.171 | 0.853 | 0.329 | 0.917* | 0.906* |

| ANS | −0.714 | −0.761 | 0.959* | −0.847 | 0.082 | −0.447 | 0.487 | 0.176 |

| ANR1 | −0.016 | −0.190 | 0.289 | −0.262 | 0.879* | 0.351 | 0.948* | 0.913* |

| ANR2 | 0.146 | −0.044 | 0.017 | −0.091 | 0.965** | 0.509 | 0.921* | 0.961** |

* Represents significant difference at 95 % probability level (p < 0.05)

** Represents significant difference at 99 % probability level (p < 0.01)

Discussion

The concentration of 7 individual catechins in tea leaves, including C, GC, EC, EGC, ECG, EGCG and GCG were determined in the current study, among which EGCG and ECG were found to be the highest fractions and GC and GCG were the lowest. With the exception of GCG, which did not differ among developmental stages, the highest concentrations of individual catechins were in new shoots. Furthermore, for new shoots, a general increase in the levels of individual catechins and total catechins was observed with increasing age of the leaves with an exception of C, whose concentration is highest in the buds. These results are similar with the results of two other studies (Eungwanichayapant and Popluechai 2009; Wei et al. 2011). In contrast, the total catechins in C. sinensis var. sinensis cultivar Zhenong 139 were found to slightly decline with increasing age of the leaves (Mamati et al. 2006). These differences might be explained by genetic variations or differences in the methods of cultivation, post-harvest treatment, environment or agricultural practices (Eungwanichayapant and Popluechai 2009; Wei et al. 2011).

Many studies have shown that gene expression and product concentration are associated with phenotypic changes. Tea catechins are considered to be synthesized through flavonoid pathway and stored in the vacuole (Suzuki et al. 2003; Rani et al. 2009). As major enzymes involved in catechin oxidation such as polyphenol oxidase (PPO) and peroxidase (POD) are present in latent forms that require activation or in different subcellular compartments, catechin degradations only occur after senescence or stresses that disorganized the cell and initiated decompartmentalization (Pourcel et al. 2007). Therefore, the expressions of catechin synthetic genes are considered to be the major factors affecting catechin contents in tea (Saito et al. 1999; Punyasin et al. 2004; Xie et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2012). In this study, the expression levels of catechin synthetic pathway genes in tea leaves at different developmental stages were analyzed. General increases of both the catechin concentrations and the expression of synthetic genes were found in new shoots, indicating their potential correlations. High correlation coefficients were identified between total catechins and CHS1 (0.964, p < 0.01), CHS2 (0.854) and CHS3 (0.896, p < 0.05) (Table 2), indicating the importance of CHS in catechin biosynthesis. Furthermore, according to the changing pattern and correlation coefficients, CHS1 seems to play a more important role in affecting catechin accumulation. In fact, the expression of CHS1 was much higher than CHS2 and CHS3 in tea leaves based on RNA-seq analysis (data not shown). Therefore, CHS1 should be paid more attention to in future studies.

In terms of catechin individuals, C had a different expression profile than the other catechins, with peak concentration in the buds, which was consistent with our previous study (Wei et al. 2011). Moreover, ANS was also the highest in the bud stage, suggesting the possibility that C conversion is predominantly regulated by ANS. Previously, it was considered that C was converted from leucocyanidin by LAR (Ashihara et al. 2010). However, from the present results, no significant correlation between the expression of LAR and C content was found (Table 2). Besides, high expression of LAR seems to lead to a high accumulation of ECG and total catechins. This raised the question about the role of LAR in tea catechin biosynthesis. Stafford (1990) found LAR is able to convert leucocyanidin to C with an epimerase, and then convert C to EC. While, transformation of CsLAR into purple tobacco plants leads to a significant decrease in anthocyanin, with accumulation of 13.7- and 7.2- fold more EC and C, respectively (Pang et al. 2013). Our results are consistent with these studies and indicate that C might be involved in the conversion of leucocyanidin to EC as an intermediate. Moreover, according to Pang’s study, CsANR1 and CsANR2 were able to convert cyanidin to a mixture of EC and C. Therefore, it is hypothesized that compared to the conversion of leucocyanidin to C by LAR, the conversion of leucocyanidin to cyanidin catalyzed by ANS, and then to C by ANRs is more important for C accumulation (Fig. 1).

On the other hand, EC, EGC, EGC and EGCG are also known to be synthesized through enzymatic reactions catalyzed by ANS and ANR (Wang et al. 2012). While the accumulation patterns of these products had similar trends with ANRs. Furthermore, correlation analysis showed both ANR1 and ANR2 were significantly and positively correlated with ECG and EGCG (Table 2). Therefore, the expressions of ANRs may comprise a rate-limiting step in ECG and EGCG productions.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that close correlations between the expressions of synthesis genes and the accumulation of catechins were present in tea plants. Based on our findings, CHS1 is more important in catechin biosynthesis than CHS2 and CHS3. ANS may regulate the conversion of C, while both ANRs and LAR may play important roles in the biosynthesis of EGCG and ECG.

Authors’ contributions

LZ carried out the molecular studies and drafted the manuscript. KW participated in the design of the study and modified the manuscript. LW participated in catechin analysis. HC participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. CZ conceived of the study and participated in its design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31470396), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LY14C020001) and the Earmarked Fund for China Agriculture Research System (CARS-23).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

- ANR

anthocyanidin reductase

- ANS

anthocyanidin synthase

- C

(+)-catechin

- CHI

chalcone isomerase

- CHS

chalcone synthase

- DFR

dihydroflavanol 4-reductase

- EC

(−)-epicatechin

- ECG

(−)-epicatechingallate

- EGC

(−)-epigallocatechin

- EGCG

(−)-epigallocatechingallate

- F3H

flavanone 3-hydroxylase

- F3′H

flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase

- F3′5′H

flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase

- FGS

flavan-3-ol gallate synthase

- FLS

flavonol synthase

- GC

(−)-gallocatechin

- GCG

(−)-gallocatechingallate

- LAR

leucocyanidin reductase

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

Footnotes

Li-Qun Zhang and Kang Wei contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Li-Qun Zhang, Email: zhang.liqun87@163.com.

Kang Wei, Email: weikang@tricaas.com.

Hao Cheng, Phone: +86 057186653169, Email: chenghao@tricaas.com.

Li-Yuan Wang, Email: wangly@tricaas.com.

Cheng-Cai Zhang, Email: zhangchengcai@tricaas.com.

References

- Ashihara H, Deng WW, Mullen W, Crozier A. Distribution and biosynthesis of flavan-3-ols in Camellia sinensis seedlings and expression of genes encoding biosynthetic enzymes. Phytochemistry. 2010;71:559–566. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow RLH, Cardelli JA. The green tea catechins, (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) and (−)-epicatechin-3-gallate (ECG), inhibit HGF/Met signaling in immortalized and tumorigenic breast epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:1922–1930. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogs J, Downey MO, Harvey JS, Ashton AR, Tanner GJ, Robinson SP. Proanthocyanidin synthesis and expression of genes encoding leucoanthocyanidin reductase and anthocyanidin reductase in developing grape berries and grapevine leaves. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:652–663. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.064238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dare AP, Tomes S, Jones M, McGhie TK, Stevenson DE, Johnson RA, Greenwood DR, Hellens RP. Phenotypic changes associated with RNA interference silencing of chalcone synthase in apple (Malus × domestica) Plant J. 2013;74:398–410. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rio D, Stewart AJ, Mullen W, Burns J, Lean ME, Brighenti F, Crozier A. HPLC-MSn analysis of phenolic compounds and purine alkaloids in green and black tea. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:2807–2815. doi: 10.1021/jf0354848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eungwanichayapant PD, Popluechai S. Accumulation of catechins in tea in relation to accumulation of mRNA from genes involved in catechin biosynthesis. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2009;47:94–97. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulati A, Rawat R, Singh B, Ravindranath SD. Application of microwave energy in the manufacture of enhanced-quality green tea. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:4764–4768. doi: 10.1021/jf026227q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning SM, Fajardo-Lira C, Lee HW, Youssefian AA, Go VLW, Heber D. Catechin content of 18 teas and a green tea extract supplement correlates with the antioxidant capacity. Nutr Cancer. 2003;45:226–235. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC4502_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higdon JV, Frei B. Tea catechins and polyphenols: health effects, metabolism, and antioxidant functions. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2003;43:89–143. doi: 10.1080/10408690390826464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Schommer CK, Kim Sym Suh DY. Cloning and characterization of chalcone synthase from the moss, Physcomitrella Patens. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:2531–2540. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiishi Y, Otani M, Takagi H, Han DS, Mori S, Tatsuzawa F, Okuhara H, Kobayashi H, Nakano M. Flower color alteration in the liliaceous ornamental Tricyrtis sp. by RNA interference-mediated suppression of the chalcone synthase gene. Mol Breed. 2012;30:671–680. doi: 10.1007/s11032-011-9653-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurauchi T, Kasai A, Tougou M, Senda M. Endogenous RNA interference of chalcone synthase genes in soybean: formation of double-stranded RNA of GmIRCHS transcripts and structure of the 5′ and 3′ ends of short interfering RNAs. J Plant Physiol. 2011;168:1264–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea AGH. Flavor, color, and stability in fruit products: The effect of polyphenols. Plant Polyphenols. Berlin: Springer; 1992. pp. 827–847. [Google Scholar]

- Mamati GE, Liang Y, Lu J. Expression of basic genes involved in tea polyphenol synthesis in relation to accumulation of catechins and total tea polyphenols. J Sci Food Agric. 2006;86:459–464. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matern U, Kneusel RE. Phenolic compounds in plant disease resistance. Phytoparasitica. 1988;16:153–170. doi: 10.1007/BF02980469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morita Y, Saito R, Ban Y, Tanikawa N, Kuchitsu K, Ando T, Yoshikawa M, Nakayama M. Tandemly arranged chalcone synthase A genes contribute to the spatially regulated expression of siRNA and the natural bicolor floral phenotype in Petunia hybrida. Plant J. 2012;70:739–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar H, Ahmad N. Tea polyphenols: prevention of cancer and optimizing health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:1698s–1702s. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1698S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang Y, Abeysinghe IS, He J, He X, Huhman D, Mewan KM, Sumner LW, Yun J, Dixon RA. Functional characterization of proanthocyanidin pathway enzymes from tea and their application for metabolic engineering. Plant Physiol. 2013;161:1103–1116. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.212050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JS, Kim JB, Hahn BS, Kim KH, Ha SH. EST analysis of genes involved in secondary metabolism in Camellia sinensis (tea), using suppression subtractive hybridization. Plant Sci. 2004;166:953–961. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2003.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pourcel L, Routaboul JM, Cheynier V, Lepiniec L, Debeaujon I. Flavonoid oxidation in plants: from biochemical properties to physiological functions. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punyasin PAN, Abeysinghe ISB, Kumar V, Treutter D, Duy D, Gosch C, Martens S, Forkmann G, Fischer TC. Flavonoid biosynthesis in the tea plant Camellia sinensis: properties of enzymes of the prominent epicatechin and catechin pathways. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;431:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rani A, Singh K, Sood P, Kumar S, Ahuja PS. p-Coumarate: CoA ligase as a key gene in the yield of catechins in tea [Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze] Funct Integr Genomics. 2009;9:271–275. doi: 10.1007/s10142-008-0098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Kobayashi M, Gong Z, Tanaka Y, Yamazaki M. Direct evidence for anthocyanidin synthase as a 2-oxoglutarate-dependent oxygenase: molecular cloning and functional expression of cDNA from a red forma of Perilla frutescens. Plant J. 1999;17:181–189. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She H, He S, Zhou Z, Zhang Q. Molecular cloning and sequences analysis of chalcone synthase gene from Fagopyrum tataricum. Informatics and Management Science I. London: Springer; 2013. pp. 649–656. [Google Scholar]

- Solovchenko A, Schmitz-Eiberger M. Significance of skin flavonoids for UV-B-protection in apple fruits. J Exp Bot. 2003;54:1977–1984. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford HA. Pathway to proanthocyanindins (condensed tannins), flavan-3-ols, and unsubstituted flavans. New York: CRC Press; 1990. pp. 63–99. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Yamazaki N, Sada Y, Oguni I, Moriyasu Y. Tissue distribution and intracellular localization of catechins in tea leaves. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2003;67:2683–2686. doi: 10.1271/bbb.67.2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi A, Matsumoto S, Hayatsu M. Chalcone synthase from Camellia sinensis: isolation of the cDNAs and the organ-specific and sugar-responsive expression of the genes. Plant Cell Physiol. 1994;35:1011–1018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner GJ, Francki KT, Abrahams S, Watson JM, Larkin PJ, Ashton AR. Proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in plants: purification of legume leucoanthocyanidin reductase and molecular cloning of its cDNA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31647–31656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302783200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomasset SC, Berry DP, Garcea G, Marczylo T, Steward WP, Gescher AJ. Dietary polyphenolic phytochemicals- promising cancer chemopreventive agents in humans? A review of their clinical properties. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:451–458. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda S, Fukui Y, Nakamura N, Katsumoto Y, Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Fukuchi-Mizutani M, Ohira K, Ueyama Y, Ohkawa H, Holton A, Kusumi T, Tanaka Y. Flower color modification of Petunia hybrida commercial varieties by metabolic engineering. Plant Biotechnol. 2004;21:377–386. doi: 10.5511/plantbiotechnology.21.377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Gao L, Wang Z, Liu Y, Sun M, Yang D, Wei C, Shan Y, Xia T. Light-induced expression of genes involved in phenylpropanoid biosynthetic pathways in callus of tea (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze) Scientia Hort. 2012;133:72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2011.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Wei K, Cheng H, He W, Li X, Gong W. Geographical tracing of Xihu Longjing tea using high performance liquid chromatography. Food Chem. 2014;146:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei K, Wang L, Zhou J, He W, Zeng J, Jiang Y, Cheng H. Catechin contents in tea (Camellia sinensis) as affected by cultivar and environment and their relation to chlorophyll contents. Food Chem. 2011;125:44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.08.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmouth RC, Turnbull JJ, Welford RWD, Clifton IJ, Prescott AG, Schofield CJ. Structure and mechanism of anthocyanidin synthase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Structure. 2002;10:93–103. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00695-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie DY, Sharma SB, Dixon RA. Anthocyanidin reductases from Medicago truncatula and Arabidopsis thaliana. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;422:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]