Abstract

In recent years, excessive oxidative metabolism has been reported as a critical determinant of pathogenicity in many diseases. The advent of a simple tool that can provide a physiological readout of oxidative stress would be a major step towards monitoring this dynamic process in biological systems, while also improving our understanding of this process. Ultra-weak photon emission (UPE) has been proposed as a potential tool for measuring oxidative processes due to the association between UPE and reactive oxygen species. Here, we used HL-60 cells as an in vitro model to test the potential of using UPE as readout for dynamically monitoring oxidative stress after inducing respiratory burst. In addition, to probe for possible changes in oxidative metabolism, we performed targeted metabolomics on cell extracts and culture medium. Lastly, we tested the effects of treating cells with the NADPH oxidase inhibitor diphenyleneiodonium chloride (DPI). Our results show that UPE can be used as readout for measuring oxidative stress metabolism and related processes.

Introduction

Respiratory burst is one of the first defence mechanisms used by specialised cells such as neutrophils in response to invading pathogens1–3. This process uses the rapid consumption of molecular oxygen (O2) to produce high levels of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) for killing invading pathogens1–3. Under homeostatic conditions, ROS are produced by mitochondria as a product of cellular metabolism4; however, during respiratory burst NADPH oxidase plays a central role in ROS production for cellular defence5, 6. The primary function of NADPH oxidase is the production of superoxide radicals (O2 · −)7, 8, which serve as the initial substrate in the generation of a diverse variety of ROS species, including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and hydroxyl radicals (OH·).

Physiologically, ROS have a hormetic effect ‒ at relatively low concentrations, ROS have beneficial properties, which include maintaining cellular redox biology and facilitating signalling9, whereas at high concentrations, ROS cause oxidative stress that can damage nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids. Studies have shown that oxidative stress contributes to the pathogenesis of many diseases and conditions, including chronic inflammation10, various types of cancers11, Alzheimer’s disease12, and cardiovascular disease13. Moreover, the aforementioned studies revealed a clear association between ROS production and NADPH oxidase, thereby providing insight into the underlying ROS-based physiological processes. In recent years, several NADPH inhibitors have been investigated as candidate therapies for ROS-related pathology14, 15, and measuring these oxidation reactions and related biomolecules can provide a readout of cellular oxidative stress16. ROS production has been analysed using various techniques, including photometry, luminometry, flow cytometry, and precipitation reactions17. However, all of these techniques provide a measure at only a single time point or require labels; moreover, these techniques are cell-dependent, laborious, and not necessarily feasible for diagnostic purposes. In contrast, ultra-weak photon emission (UPE) is a promising new tool that could be used to monitor oxidative processes. Indeed, the feasibility of using UPE as a tool for monitoring health and disease has been examined in several studies18–20.

Ultra-weak photons are emitted spontaneously by many biological systems21, 22. UPE is characterised as non-thermal radiation in the near-ultraviolet to visible region (100–800 nm) of the electromagnetic spectrum, possibly reaching the near-infrared region (801–1300 nm). UPE is generated by the transition of electrons from an excited state to the ground state; excited electron states (e.g. triplet carbonyls, singlet oxygen, etc.) are produced by the oxidation of biomolecules by ROS21, 23. Thus, UPE is a potential new tool for monitoring dynamic biological processes that involve ROS, including ROS-related diseases24, 25, as well as processes related to oxidative stress metabolism. A clear advantage of UPE is that it provides spatiotemporal information; in addition, UPE is non-damaging, non-invasive, label-free, and relatively cost-effective.

Because UPE can reflect complex molecular processes, it can be combined with other technologies such as metabolomics, thereby providing valuable insight into the biochemical processes probed using UPE26. Recently, we used metabolomics to identify several metabolites correlated with UPE27. Moreover, metabolomics is a powerful approach that can be applied to numerous biological studies due to the ability to detect many hundreds of metabolites in a single biological sample, thereby providing a ‘phenotypic’ readout of other ‘omics’. Previous reports suggest that lipid peroxidation of linoleic acid in cell membranes can strongly affect UPE emission18, 28. In this respect, the products of lipid and protein oxidation are closely related to UPE. For example, compounds related to the arachidonic acid pathway (e.g. isoprostanes, prostaglandins, and lysosphingolipids) are key signalling compounds in biological systems and are often related to oxidative stress and/or inflammatory processes29, 30. In addition, previous studies demonstrated the relationship between these metabolites and low-level chemiluminescence and electronically excited species31–34.

Here, we evaluated the feasibility of using UPE as a dynamic tool for monitoring oxidative stress metabolism and related processes. A metabolomics approach was also used to gain insight into the biochemical processes probed using UPE. We used differentiated neutrophil-like HL-60 cells as an in vitro model. Respiratory burst was induced by treating the cells with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)35, 36; in response to PMA, these cells produce large quantities of ROS, which were monitored in real-time using UPE. A targeted metabolomics approach was then used to analyse metabolites related to oxidative stress and inflammation (e.g. prostaglandins and isoprostanes) in HL-60 cell extracts and culture medium. Moreover, we measured the effects of treating cells with the NADPH oxidase inhibitor diphenyleneiodonium chloride (DPI).

Results

Ultra-weak photon emission (UPE)

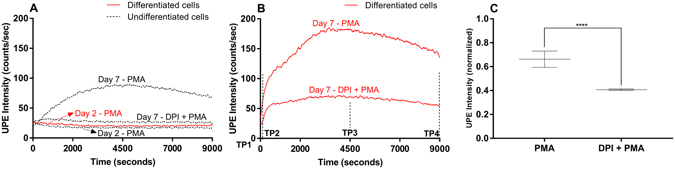

HL-60 cells were differentiated into neutrophil-like cells by incubation in all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) for up to 7 days. Next, we induced respiratory burst by treating the cells with PMA. After PMA induction we measured the dynamic UPE profile for 9000 seconds (Fig. 1). Figure 1A shows control experiments recorded under the same conditions and Fig. 1B presents the UPE profile of differentiated cells on Day 7 induced by PMA in the presence or absence of DPI. Figure 1C illustrates the paired t-test performed (n = 5).

Figure 1.

Dynamic UPE measurement of HL-60 cells treated with ATRA for 2 or 7 days to differentiate the cells into neutrophil-like cells. The lines (red - differentiated cells and black - undifferentiated cells) represent the moving UPE average of 100 points. (A) Control measurements. (B) The UPE profile of differentiated cells (day 7) was recorded after stimulation with PMA in the absence or presence of DPI. (C) Summary of peak UPE intensity measured in HL-60 cell treated for 7 days with ATRA after stimulation with PMA in the absence or presence of DPI. The data are represented as the mean ± SD (n = 5) of the normalized maximum peak intensity. Student’s paired t-test with ****p < 0.0001.

Cells treated with ATRA for only 2 days had no response to PMA stimulation. In contrast, cells treated with ATRA for 7 days had a robust increase in UPE in response to PMA due to a high amount of ROS generated. This profile is in agreement with our previous work27. Treating the differentiated cells with the NADPH oxidase inhibitor DPI significantly reduced (p < 0.0001) the UPE response, substantiating the biochemical link between ROS and UPE. Furthermore, this inhibition was also observed in undifferentiated cells (see Fig. 1A ) due to a small percentage of cells spontaneously differentiating into neutrophils-like cells27.

Metabolic profiling of isoprostanes, prostaglandins and lysosphingolipids

Next, to measure the biochemical changes related to oxidative metabolism, we performed targeted metabolomics of compounds related to oxidative stress and inflammation, including prostaglandins, isoprostanes, nitro-fatty acids, and lysosphingolipids. We used our previously reported approach27 (see also Figure S1), and DPI treatment was included in order to determine which metabolic pathways may be involved in this process.

Based on the dynamic UPE profiles (see Fig. 1B and Figure S1), cell lysates (to measure intracellular metabolites) and culture medium samples (to measure extracellular metabolites) were obtained at four time points relative to PMA stimulation and analysed using targeted metabolomics. TP1 corresponds to the basal condition (i.e. prior to the addition of PMA), and TP2, TP3 and TP4 correspond to 60, 4500 and 9000 seconds after PMA stimulation, respectively. To measure the metabolic profiles indicative of oxidative stress and inflammation, we used a custom-built liquid chromatography‒mass spectrometry platform37. A total of 10 and 11 metabolites were detected in the cell lysates and culture medium samples, respectively; 7 metabolites were detected in both samples (Table S1).

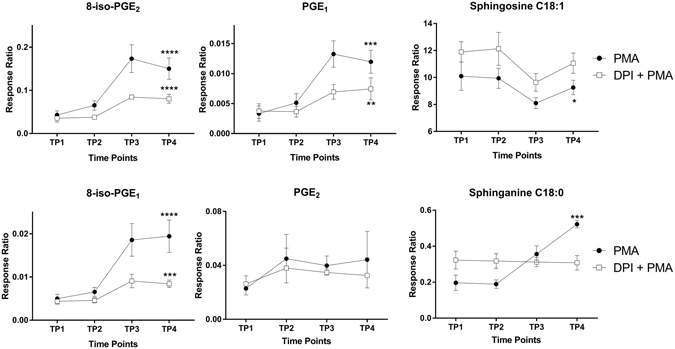

Intracellular metabolites

Among the 10 intracellular metabolites measured in the cell lysates, only 8-iso-PGE2, 8-iso-PGE1, PGE1 and sphinganine C18:0 increased significantly in response to PMA stimulation, and sphingosine C18:1 significantly decreased in response to PMA stimulation shown in Fig. 2 and Table S2. PGE2 did display an increasing trend over the four time points. We also found a significant correlation between the recorded UPE data and the metabolites measured (see Table S2).

Figure 2.

HL-60 cells were treated with ATRA for 7 days, after which respiratory burst was induced with PMA in the presence or absence of DPI. Cell lysates were collected at the indicated time points, and intracellular metabolites were measured. We performed intragroup ANOVA analysis over the four time points to identify significant changes in metabolite levels. Data are plotted as the mean ± SD (n = 3). ANOVA with *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

Pre-treating the cells with DPI significantly decreased the PMA-induced responses of 8-iso-PGE2, 8-iso-PGE1 and PGE1. In addition, the PMA-induced response of sphingosine increased, whereas sphinganine C18:0 had no response (see Fig. 2).

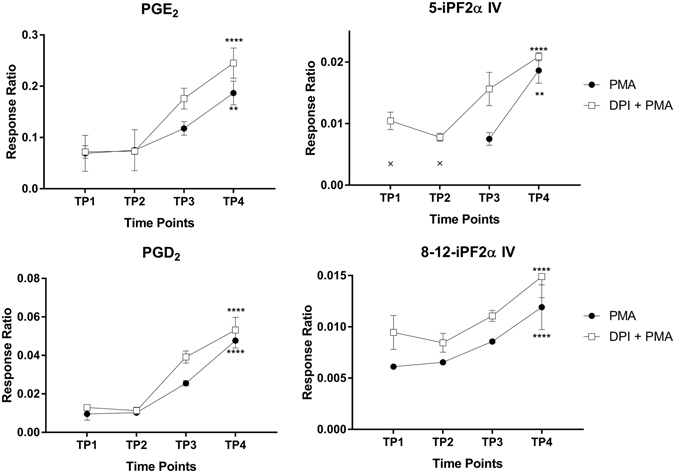

Extracellular metabolites

Next, we examined the extracellular metabolites measured from the culture medium during PMA-induced respiratory burst. Among the 11 compounds detected (see Table S1 ), only PGE2, PGD2, (±)5-iPF2α-IV, and 8-12-iPF2α-IV increased significantly during respiratory burst (Fig. 3 and Table S3). Interestingly, treating the cells with DPI also increased the extracellular levels of all four compounds. Spearman’s correlation showed a high correlation coefficient (r > 0.6) to the extracellular metabolite levels and the measured UPE intensity. However, the p-values were not significant (p > 0.05).

Figure 3.

HL-60 cells were treated with ATRA for 7 days, after which respiratory burst was induced with PMA in the presence or absence of DPI. Culture medium was collected at the indicated time points, and extracellular metabolites were measured. We performed intragroup ANOVA analysis over the four time points to identify significant changes in metabolite levels. Data are plotted as the mean ± SD (n = 3/group). ANOVA with **p < 0.01 and ****p < 0.0001. The data points indicated with an “x” in the top-right panel were below the metabolite’s limit of detection.

Discussion

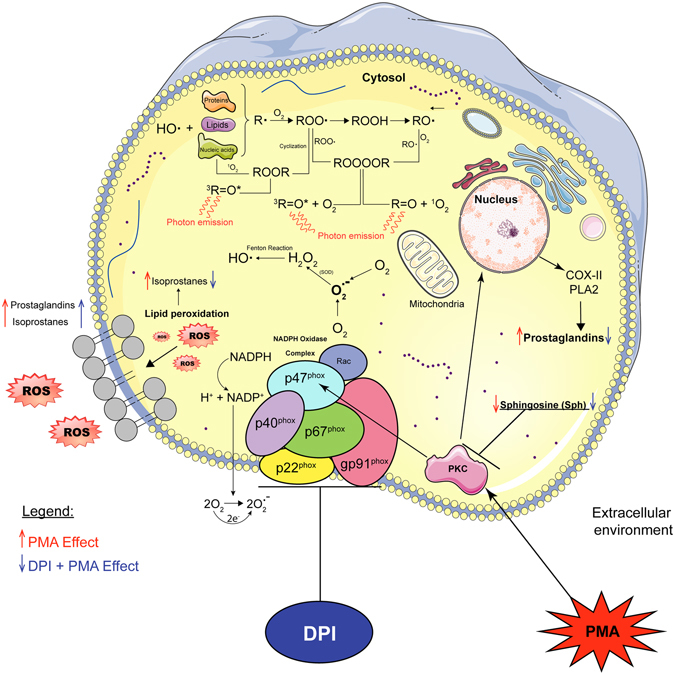

Treating HL-60 cells with ATRA causes the cells to differentiate into neutrophil-like cells35. Neutrophils are specialised cells capable of producing high amounts of ROS. In addition, the differentiation of HL-60 cells into neutrophil-like cells is associated with morphological changes, as well as metabolic changes that occur at the cell surface and in the nucleus35, 38, 39. We used PMA to induce respiratory burst, thereby activating protein kinase C (PKC). PKC phosphorylates the cytosolic NADPH oxidase subunit p47PHOX, contributing to assembly of the NADPH oxidase complex40–42. The function of NADPH oxidase is to extract electrons from NADPH, transferring the electrons to oxygen, thereby forming O2 · − in the cytosol and extracellular space; this ultimately leads to the generation of other ROS species5–7. Here, we found that UPE can be used to establish the link between respiratory burst and increased levels of ROS in response to PMA stimulation (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Schematic overview of the biological events involved in NADPH oxidase during PMA-induced respiratory burst in differentiated HL-60 cells. PMA activates protein kinase C (PKC), which signals to the nucleus, activating cyclooxygenase (COX) and phospholipase A2 (PLA2) pathways, leading to the production of prostaglandins. O2 .−is first produced by NADPH oxidase as a primary ROS and is subsequently dismutated to H2O2 by superoxide dismutase (SOD). Thus, H2O2 serves as a substrate for generating hydroxyl radicals (OH•) via the Fenton reaction. Hydroxyl radicals (OH•) are potent oxidants that can produce the initial radical (R•) form of a wide range of biomolecules, including lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids. Via this mechanism, molecular oxygen is added to produce a peroxyl radical (ROO•), followed by cyclisation to produce dioxetane (ROOR) and decomposition to produce triplet excited carbonyl23. Alternatively, two ROO• moieties can recombine to form tetroxide (ROOOOR), which can decompose to form triplet excited carbonyl or singlet oxygen via the Russel reaction23. These electron-excited species emit photons, giving rise to UPE23. Eventually, intracellular ROS can react with biomolecules in the cell membrane (i.e. lipid peroxidation), giving rise to isoprostanes. Treating differentiated HL-60 cells with DPI, which binds to the NADPH oxidase complex, partially inhibits ROS production, decreases UPE emission, and decreases the levels of prostaglandins and isoprostanes. This figure was drawn by the first author R.C.R. Burgos using the software Adobe Illustrator and the image bank of Servier Medical Art. Servier Medical Art by Servier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/.

The NADPH oxidase inhibitor DPI binds specifically to the flavoprotein subunit (a polypeptide in the plasma membrane - cytochrome b558), thereby blocking the flow of electrons in the NADPH oxidase complex5, 6, 43–45. DPI has also been used to inhibit mitochondrial ROS production46. In our study, DPI significantly decreased the UPE signal in PMA-stimulated differentiated HL-60 cells. Interestingly, DPI also acts by suppressing O2 · − production, H2O2 production, and mitochondrial processes such as NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I)43, 44, 46 (see Fig. 4). In our study, we used DPI at its reported IC50 value(0.9 µM)44. At this concentration, DPI caused a 50–60% decrease in the UPE signal, suggesting residual electron transport flow, likely due to residual NADPH oxidase activity and the relatively low levels of photon emissions from mitochondrial activity.

With respect to intracellular metabolites, isoprostanes such as 8-iso-PGE2 and 8-iso-PGE1 are non-enzymatic products produced by the auto-oxidation of arachidonic acid by free radicals; thus, these metabolites are useful markers of oxidative stress30. In biological processes involving ROS, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) ‒ particularly arachidonic acid ‒ are susceptible to oxidation by free radicals. PUFAs also serve as a precursor for cyclooxygenase-mediated oxidation, producing thromboxanes, prostacyclins, and prostaglandins30, 47, 48.

Although the production of the isoprostane 8-iso-PGE1 is poorly understood, one study reported that E1-isoprostane is produced in plants by oxidation, with α-linoleic acid as the substrate49. Similarly, little is known regarding the production and biological role of 8-iso-PGE2. In a previous in vivo study with rats, 8-iso-PGE2 was identified as a non-enzymatic product of free radical‒catalysed lipid peroxidation, ultimately exerting potent biological activity (in this case, renal vasoconstriction)50. Another biological role of 8-iso-PGE2 is the ability to inhibit platelet aggregation51. Thus, 8-iso-PGE2 appears to act as a signalling molecule with a wide range of biological functions.

The prostaglandins PGE1 and PGE2 have been well characterised and mediate a variety of biological processes, including vasodilation52, platelet aggregation53, and adaptive crosstalk activation54. Here, we found that the intracellular levels of both 8-iso-PGE2 and 8-iso-PGE1 are increased during respiratory burst in differentiated HL-60 cells; therefore, these metabolites are presumably products of ROS oxidation mediated by NADPH oxidase and mitochondrial electron transport. Moreover, pre-treating cells with DPI significantly reduced the intracellular levels of isoprostanes and prostaglandins (see Fig. 2). Taken together, our results show that DPI treatment significantly decreases the intracellular levels of 8-iso-PGE1, 8-iso-PGE2, and PGE1, thereby showing a clear correlation with UPE intensity.

Sphingosine and sphinganine are lysosphingolipids that serve as precursors for ceramide and/or sphingosine-1-phosphate, both of which are involved in various signalling pathways, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis55. In addition, both sphingosine and sphinganine can inhibit PKC activity56, 57 (see Fig. 4). PKC phosphorylates p47PHOX, a key component of NADPH oxidase (see Fig. 4), and therefore contributes to the activation of respiratory burst by inducing flavoenzyme (cytochrome b558)44. Our finding of increased levels of sphinganine, however, suggests that PKC activity has an inhibitory role, acting as a negative regulator of respiratory burst. During respiratory burst, sphingosine C18:1 decreased significantly (see Fig. 2). Previous studies found that sphingosine is converted to N,N-dimethyl sphingosine (DMS), which has an even stronger inhibitory effect on PKC58. This may explain the decrease in sphingosine C18:1; however, DMS was not included in our analysis.

E-series prostaglandins play a role in cell signalling by activating E2 and E4 prostanoid receptors located on the neutrophils47. In a negative feedback mechanism, receptor E2 and E4 activation increases intracellular levels of cAMP inhibiting neutrophil extracellular traps59 and the respiratory burst60. This may explain the increased extracellular levels of E-series prostaglandins, including PGE2 as a protective mechanism.

PGD2 has both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory properties and is considered one of the major mediators of the mast cell allergic response and can serve as a potent eosinophil chemoattractant61, 62. During respiratory burst, PGD2 is rapidly metabolised through enzymatic and non-enzymatic pathways to 11-epi-PGF2α, dihydro-15-keto-PGD2, and PGJ2 in order to attract eosinophils to inflammatory sites61. However, PGJ2 was not included among the metabolites analysed in the current study. Thus, PGD2 may be produced during respiratory burst in order to attract other immune cells (e.g. eosinophils), thereby further stimulating the immune response at the site of inflammation. We hypothesise that ROS generated by NADPH oxidase during respiratory burst induces lipid peroxidation in the cell membrane. Thus, prostaglandins and isoprostanes are secreted into the extracellular space during membrane repair (see Fig. 4). Although our analysis revealed significant PMA-induced changes in PGE2, PGD2, (±)5-iPF2α-IV, and 8-12-iPF2α-IV in the medium, DPI had the same effect, with slightly increased levels.

Taken together, these results suggest that UPE is correlated only with intracellular signalling metabolic intermediates. These findings strongly support the notion that UPE is linked to intracellular metabolism. Another explanation for the results of our analysis of extracellular metabolites is that the time course of respiratory burst (measured up to 9000 seconds) was too short for studying the flow of metabolites from the cytoplasm to the extracellular medium.

In summary, we report a strong correlation between ultra-weak photon emission intensity, NADPH oxidase activity and intracellular metabolism. The intracellular levels of the isoprostanes 8-iso-PGE1 and 8-iso-PGE2 and the prostaglandin PGE1 significantly increased during PMA-induced respiratory burst, and DPI inhibited 50–60% of the PMA-induced UPE signal. These results indicate that UPE can be used as a dynamic readout tool in combination with metabolomics to monitor oxidative metabolism in ROS-related physiological processes. Follow-up studies should focus on identifying the specific radical species using spin-trapping electron paramagnetic resonance, which may also help identify the molecules that undergo oxidative damage. Optical spectral analysis of the UPE signal may also help identify the specific photon-emitting molecules.

Methods

Cell culture and experimental design

All experiments with human cell lines were performed in accordance with approved guidelines, and all experimental protocols were approved in accordance with the regulations established by the Institute of Photonics and Electronics, Czech Academy of Sciences. The acute promyelocytic leukaemia cell line HL-60 (catalogue number CCL-240; lot number 62690063; ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (IMDM) without phenol red (Gibco-Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum and 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in an incubator at 37 °C in 5% CO2. The cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells/ml and maintained in the exponential growth phase in accordance with the instructions provided by ATCC. Cell number and viability were measured using the trypan blue exclusion method with an automated cell counter (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Cell viability was >85%. UPE and metabolomics measurements were performed at cell passage number 28. We have used the experimental design as described previously27, with minor modifications. In brief, when the cells were split and adjusted for cell density, 1 µM all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA; 98% grade, catalogue number R250, Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the cells in order to induce differentiation via the granulocytic pathway; control cells received the same volume of vehicle. The cells were then incubated for up to 7 days, and UPE and metabolomics experiments were performed on days 2 and 7. Prior to any UPE measurement and/or sample collection for metabolomics, the culture medium was replaced with fresh IMDM (without supplementation), and the cells were counted. Where indicated, cells were stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; 98% grade, Sigma-Aldrich) in the presence or absence of diphenyleneiodonium chloride (DPI; Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI). A small aliquot of the cell suspension was used for UPE measurements. Based on the UPE profile, four time points were used for the metabolomics study; aliquots containing of 12 × 106 cells were used for each time point. TP1 samples were collected prior to PMA induction; TP2, TP3, and TP4 samples were collected 60, 4500, and 9000 seconds, respectively, after PMA induction (see Figure S1).

Ultra-weak photon emission (UPE)

UPE was measured using a module H7360-01 photomultiplier tube (PMT; Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan), which is sensitive to wavelengths of 300–650 nm and has a dark count of approximately 13 counts per second. UPE was measured from HL-60 cells suspended in IMDM without any supplementation. The cell suspension (3 ml containing 1.5 × 106 cells/ml) was transferred to a small Petri dish, which was then placed in the PMT dark chamber at 37 °C. The Petri dish was positioned as close as possible to the PMT detector using a sample holder. A background measurement was taken before each sample measurement. To stimulate the respiratory burst in cells, PMA was applied at a concentration of 54 nM, and the UPE profile was recorded for 9000 seconds. DPI was applied at a concentration of 0.9 µM prior to PMA (54 nM) stimulation in independent cell suspensions after which the UPE profile was recorded for 9000 seconds. There was a brief delay of approximately 30 seconds between PMA application and the start of the UPE measurement due to placing the samples in the PMT dark chamber. Control cells (i.e. cells that were not cultured in ATRA) were measured using the same conditions.

Collection, quenching, and extraction of cell pellets and culture medium for metabolomics

Sample collection and quenching

Aliquots of suspension cells were centrifuged for 4 minutes at 0.2 rcf at room temperature. The supernatant (containing the culture medium) was collected and stored at −80 °C. The pellets (containing the cells) were quenched in 0.9% (w/v) sodium chloride solution (Sigma-Aldrich) at 0–2 °C. The cell aliquots were then centrifuged for 4 minutes at 0.2 rcf at room temperature. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellets were stored at −80 °C.

Extraction

The medium and cell pellets were extracted using a liquid-liquid extraction protocol as described below.

Cell pellets–First, each cell pellet was suspended in 500 µl citric acid (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), 5 µl antioxidant containing 0.4 mg/ml butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT; Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.4 mg/ml ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; Sigma-Aldrich), 10 µl internal standard mix (ISTD) comprised of deuterated compounds (Cayman Chemicals), and 1 ml n-butanol (Boom B.V., Meppel, the Netherlands):ethyl acetate (Biosolve B.V., Valkenswaard, the Netherlands). The cell suspension was shaken in a bullet blender (Next Advance, Averill Park, NY) to mix the organic phase and lyse the cells. The suspension was then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 16.1 rcf at 4 °C, and 900 µl of the organic phase was collected from each sample. The remaining mixture was subjected to a second extraction round with 400 µl n-butanol (saturated in Milli-Q water from EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) and 400 µl of ethyl acetate. The mixture was then shaken and centrifuged, and 800 µl of the organic phase was collected and added to the first-round organic phase sample. Finally, the organic phase was dried in a CentriVap centrifugal concentrator. The dried samples were resuspended in 30 µl injection solution consisting of 70% MeOH (Biosolve B.V.) in Milli-Q water and transferred to a glass vial suitable for use in the LC system.

Medium samples–Medium samples (800 µl total) were divided into two 400-µl aliquots to increase the concentration of extracellular metabolites. First, we added 400 µl citric acid, 5 µl antioxidant (0.4 mg/ml BHT and 0.4 mg/ml EDTA), 6 µl ISTD mix, and 1 ml butanol:ethyl acetate to each aliquot. The samples were then shaken using a bullet blender, centrifuged for 10 minutes at 16.1 rcf at 4 °C, and 950 µl of the organic phase was collected. The remaining mixture was subjected to a second extraction round with 500 µl butanol saturated in Milli-Q water and 500 µl of ethyl acetate. The mixture was then shaken and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 16.1 rcf at 4 °C; 950 µl of the organic phase was collected and added to the first-round organic phase sample. The organic phase was dried using a CentriVap centrifugal concentrator. The dried samples were resuspended in 30 µl injection solution (70% MeOH in Milli-Q water) and transferred to a glass vial suitable for use in the LC system.

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis

For metabolomics, a model LCMS-8050 liquid chromatograph-mass spectrometer (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) and an ACQUITY BEH C18 column (50 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm; Waters, Milford, MA) maintained at 40 °C was used for reverse-phase LC separation. Electrospray ionisation was used as an ionisation source. The mobile phase A consisted of H2O containing 0.1% acetic acid. The mobile phase B contained 75% acetonitrile, 25% MeOH, and 0.1% acetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich). The mobile phase C contained 100% isopropanol. The temperature of the column was set at 40 °C, and the temperature of the autosampler was set at 5 °C. The injection volume and flow rate were 10 µl and 0.7 ml/min, respectively. After each measurement, peak detection and integration of the raw data were processed and analysed using the Shimadzu Lab Solutions software program, version 5.65. Pooled cell pellet extracts and pooled medium samples were prepared and measured after every ten samples in order to verify reliability of the measurements. Any metabolites detected in the pooled samples that exceeded 30% of the relative standard deviation due to technical and/or analytical variations were excluded from analysis.

Statistical analysis

UPE data were analysed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). The two-tailed paired Student’s t-test was used to compare individual groups. The metabolic results (i.e. response ratio) were uploaded to the MetaboAnalyst website (http://www.metaboanalyst.ca)63, 64 and tested for statistical significance. To obtain data with a normal distribution, the metabolomics data were log-transformed and auto-scaled. We analysed the following parameters: (i) the variance between the four time points (i.e. TP1, TP2, TP3, and TP4) relative to PMA stimulation was analysed using a two-way ANOVA (two-tailed); (ii)) the variance between the four time points in cells treated with DPI and PMA were analysed using a two-way ANOVA (two-tailed); and (iii)) Spearman’s correlation coefficient (two-tailed) was used to analyse the relationship between the UPE data and metabolic profile. Spearman’s correlations were done independently for the PMA and DPI + PMA groups, correlating their averaged metabolite levels to their respective averaged UPE profiles over the four TPs measured. Differences with a p-value < 0.05 were considered significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Ultra-weak photon emission as a dynamic tool for monitoring oxidative stress metabolism

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by CNPq, the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development – Brazil. R.C.R.B. is the recipient of a scholarship from Science without Borders (scholarship number 230827/2012-8). The authors thank Dr Slavik Koval for help with statistical analyses.

Author Contributions

R.C.R.B., J.C.S., and L.W. conducted the experiments and analysed the results. K.C. prepared the cell cultures and helped write the manuscript. R.C.R.B. and R.B. designed the study. R.C.R.B. and J.C.S. wrote the manuscript. M.C., E.W., R.R., J.G., and T.H. supervised the research. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript. M.C. and K.C. acknowledge Czech Science Foundation project GP13-29294S and participate in COST Actions BM1309, CA15211 and bilateral exchange project between Czech and Slovak Academies of Sciences, no. SAV-15-22.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01229-x

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Babior, B. M. The respiratory burst oxidase. In: Molecular Aspects of Inflammation (Sies, H., Flohe, L., Zimmer, G. Eds). Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. 41–47 (1991).

- 2.Dahlgren C, Karlsson A. Respiratory burst in human neutrophils. Journal of immunological methods. 1999;232:3–14. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(99)00146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glass GA, et al. The respiratory burst oxidase of human neutrophils. Further studies of the purified enzyme. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261:13247–13251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bylund J, Björnsdottir H, Sundqvist M, Karlsson A, Dahlgren C. Measurement of respiratory burst products, released or retained, during activation of professional phagocytes. Neutrophil methods and protocols. 2014;1124:321–338. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-845-4_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bylund J, Brown KL, Movitz C, Dahlgren C, Karlsson A. Intracellular generation of superoxide by the phagocyte NADPH oxidase: how, where, and what for? Free Radic Biol and Med. 2010;49:1834–1845. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panday A, Sahoo MK, Osorio D, Batra S. NADPH oxidases: an overview from structure to innate immunity-associated pathologies. Cell Mol Immunol. 2015;12:5–23. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babior BM. NADPH oxidase: an update. Blood. 1999;93:1464–1476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ray PD, Huang BW, Tsuji Y. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular signaling. Cell Signal. 2012;24:981–990. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartsch H, Nair J. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress in the genesis and perpetuation of cancer: role of lipid peroxidation, DNA damage, and repair. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2006;391:499–510. doi: 10.1007/s00423-006-0073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar B, Koul S, Khandrika L, Meacham RB, Koul HK. Oxidative stress is inherent in prostate cancer cells and is required for aggressive phenotype. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1777–1785. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perry G, Castellani RJ, Hirai K, Smith MA. Reactive Oxygen Species Mediate Cellular Damage in Alzheimer Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 1998;1:45–55. doi: 10.3233/JAD-1998-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugamura K, Keaney JF., Jr. Reactive oxygen species in cardiovascular disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:978–992. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altenhofer S, Radermacher KA, Kleikers PW, Wingler K, Schmidt HH. Evolution of NADPH Oxidase Inhibitors: Selectivity and Mechanisms for Target Engagement. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2015;23:406–427. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drummond GR, Selemidis S, Griendling KK, Sobey CG. Combating oxidative stress in vascular disease: NADPH oxidases as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:453–471. doi: 10.1038/nrd3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schieber M, Chandel NS. ROS function in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr Biol. 2014;24:R453–462. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bylund J, Bjornsdottir H, Sundqvist M, Karlsson A, Dahlgren C. Measurement of respiratory burst products, released or retained, during activation of professional phagocytes. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1124:321–338. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-845-4_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prasad A, Pospisil P. Linoleic acid-induced ultra-weak photon emission from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii as a tool for monitoring of lipid peroxidation in the cell membranes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rastogi A, Pospisil P. Ultra-weak photon emission as a non-invasive tool for the measurement of oxidative stress induced by UVA radiation in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2013;123:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ives JA, et al. Ultraweak photon emission as a non-invasive health assessment: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cifra M, Pospisil P. Ultra-weak photon emission from biological samples: definition, mechanisms, properties, detection and applications. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2014;139:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devaraj, B., Usa, M. & Inaba, H. Biophotons: Ultraweak light emission from living systems. Curr Opin Solid St M2, 188–193, doi:10.1016/S1359-0286(97)80064-2 (1997).

- 23.Pospisil P, Prasad A, Rac M. Role of reactive oxygen species in ultra-weak photon emission in biological systems. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2014;139:11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Wijk R, Van Wijk EP, Wiegant FA, Ives J. Free radicals and low-level photon emission in human pathogenesis: state of the art. Indian J Exp Biol. 2008;46:273–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rastogi A, Pospisil P. Spontaneous ultraweak photon emission imaging of oxidative metabolic processes in human skin: effect of molecular oxygen and antioxidant defense system. J Biomed Opt. 2011;16:096005. doi: 10.1117/1.3616135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burgos RC, van Wijk EP, van Wijk R, He M, van der Greef J. Crossing the Boundaries of Our Current Healthcare System by Integrating Ultra-Weak Photon Emissions with Metabolomics. Front Physiol. 2016;7:611. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burgos RC, et al. Tracking biochemical changes correlated with ultra-weak photon emission using metabolomics. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2016;163:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galantsev VP, Kovalenko SG, Moltchanov AA, Prutskov VI. Lipid peroxidation, low-level chemiluminescence and regulation of secretion in the mammary gland. Experientia. 1993;49:870–875. doi: 10.1007/BF01952600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCarthy MK, Weinberg JB. Eicosanoids and respiratory viral infection: coordinators of inflammation and potential therapeutic targets. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:236345–13. doi: 10.1155/2012/236345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montuschi P, Barnes PJ, Roberts LJ. 2nd. Isoprostanes: markers and mediators of oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2004;18:1791–1800. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2330rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cadenas, E., Boveris, A. & Chance, B. In Free Radicals in Biology 211–242 (Academic Press, 1984).

- 32.Cadenas E, Sies H. Formation of electronically excited states during the oxidation of arachidonic acid by prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase. Methods Enzymol. 2000;319:67–77. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(00)19009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cadenas E, Sies H, Nastainczyk W, Ullrich V. Singlet oxygen formation detected by low-level chemiluminescence during enzymatic reduction of prostaglandin G2 to H2. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1983;364:519–528. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1983.364.1.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakano M. Low-level chemiluminescence during lipid peroxidations and enzymatic reactions. J Biolumin Chemilumin. 1989;4:231–240. doi: 10.1002/bio.1170040133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breitman TR, Selonick SE, Collins SJ. Induction of differentiation of the human promyelocytic leukemia cell line (HL-60) by retinoic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:2936–2940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levy R, Rotrosen D, Nagauker O, Leto TL, Malech HL. Induction of the respiratory burst in HL-60 cells. Correlation of function and protein expression. J Immunol. 1990;145:2595–2601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fu J, et al. Metabolomics profiling of the free and total oxidised lipids in urine by LC-MS/MS: application in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2016;408:6307–6319. doi: 10.1007/s00216-016-9742-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collins SJ. The HL-60 promyelocytic leukemia cell line: proliferation, differentiation, and cellular oncogene expression. Blood. 1987;70:1233–1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gallagher R, et al. Characterization of the continuous, differentiating myeloid cell line (HL-60) from a patient with acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 1979;54:713–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dang PM, Fontayne A, Hakim J, El Benna J, Perianin A. Protein kinase C zeta phosphorylates a subset of selective sites of the NADPH oxidase component p47phox and participates in formyl peptide-mediated neutrophil respiratory burst. J Immunol. 2001;166:1206–1213. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.el Benna J, Faust LP, Babior BM. The phosphorylation of the respiratory burst oxidase component p47phox during neutrophil activation. Phosphorylation of sites recognized by protein kinase C and by proline-directed kinases. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23431–23436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tardif M, Rabiet MJ, Christophe T, Milcent MD, Boulay F. Isolation and characterization of a variant HL60 cell line defective in the activation of the NADPH oxidase by phorbol myristate acetate. J Immunol. 1998;161:6885–6895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cross AR, Jones OT. The effect of the inhibitor diphenylene iodonium on the superoxide-generating system of neutrophils. Specific labelling of a component polypeptide of the oxidase. Biochem J. 1986;237:111–116. doi: 10.1042/bj2370111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hancock JT, Jones OTG. The Inhibition by Diphenyleneiodonium and Its Analogs of Superoxide Generation by Macrophages. Biochemical Journal. 1987;242:103–107. doi: 10.1042/bj2420103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y, Fiskum G, Schubert D. Generation of reactive oxygen species by the mitochondrial electron transport chain. J Neurochem. 2002;80:780–787. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2002.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Y, Trush MA. Diphenyleneiodonium, an NAD(P)H oxidase inhibitor, also potently inhibits mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 1998;253:295–299. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buczynski MW, Dumlao DS, Dennis EA. Thematic Review Series: Proteomics. An integrated omics analysis of eicosanoid biology. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:1015–1038. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R900004-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fullerton JN, O’Brien AJ, Gilroy DW. Lipid mediators in immune dysfunction after severe inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2014;35:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parchmann S, Mueller MJ. Evidence for the Formation of Dinor Isoprostanes E1from α-Linolenic Acid in Plants. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32650–32655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morrow JD, et al. Free radical-induced generation of isoprostanes in vivo. Evidence for the formation of D-ring and E-ring isoprostanes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4317–4326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Longmire AW, Roberts LJ, Morrow JD. Actions of the E2-isoprostane, 8-ISO-PGE2, on the platelet thromboxane/endoperoxide receptor in humans and rats: additional evidence for the existence of a unique isoprostane receptor. Prostaglandins. 1994;48:247–256. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(94)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson JR, Kapoor SC. Contribution of prostaglandins to exercise-induced vasodilation in humans. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:H171–175. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.1.H171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith JB. Prostaglandins and platelet aggregation. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1981;651:91–99. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1981.tb03638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rieser C, Bock G, Klocker H, Bartsch G, Thurnher M. Prostaglandin E2 and tumor necrosis factor alpha cooperate to activate human dendritic cells: synergistic activation of interleukin 12 production. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1603–1608. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Brocklyn JR, Williams JB. The control of the balance between ceramide and sphingosine-1-phosphate by sphingosine kinase: oxidative stress and the seesaw of cell survival and death. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2012;163:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lambeth J, Burnham D, Tyagi S. Sphinganine effects on chemoattractant-induced diacylglycerol generation, calcium fluxes, superoxide production, and on cell viability in the human neutrophil. Delivery of sphinganine with bovine serum albumin minimizes cytotoxicity without affecting inhibition of the respiratory burst. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:3818–3822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hannun YA, Loomis CR, Merrill AH, Jr., Bell RM. Sphingosine inhibition of protein kinase C activity and of phorbol dibutyrate binding in vitro and in human platelets. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:12604–12609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Satoshi K, et al. Effect of sphingosine and its N-methyl derivatives on oxidative burst, phagokinetic activity, and trans-endothelial migration of human neutrophils. Biochemical pharmacology. 1992;44:1585–1595. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90476-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shishikura K, et al. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits neutrophil extracellular trap formation through production of cyclic AMP. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2016;173:319–331. doi: 10.1111/bph.13373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mitsuyama T, Takeshige K, Minakami S. Cyclic AMP inhibits the respiratory burst of electropermeabilized human neutrophils at a downstream site of protein kinase C. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research. 1993;1177:167–173. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(93)90036-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heinemann A, Schuligoi R, Sabroe I, Hartnell A, Peskar BA. Delta 12-prostaglandin J2, a plasma metabolite of prostaglandin D2, causes eosinophil mobilization from the bone marrow and primes eosinophils for chemotaxis. J Immunol. 2003;170:4752–4758. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saito S, Tsuda H, Michimata T. Prostaglandin D2 and reproduction. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2002;47:295–302. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0897.2002.01113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xia J, Mandal R, Sinelnikov IV, Broadhurst D, Wishart DS. MetaboAnalyst 2.0-a comprehensive server for metabolomic data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W127–133. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xia J, Sinelnikov IV, Han B, Wishart DS. MetaboAnalyst 3.0-making metabolomics more meaningful. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W251–257. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Ultra-weak photon emission as a dynamic tool for monitoring oxidative stress metabolism