Abstract

Mammalian skeletal muscles contain a number of heterogeneous cell populations. Our previous study characterized a unique population of myogenic lineage stem cells that can be isolated from adult mammalian skeletal muscles upon injury. These injury-induced muscle-derived stem cell-like cells (iMuSCs) displayed a multipotent state with sensitiveness and strong migration abilities. Here, we report that these iMuSCs have the capability to form neurospheres that represent multiple neural phenotypes. The induced neuronal cells expressed various neuron-specific proteins, their mRNA expression during neuronal differentiation recapitulated embryonic neurogenesis, they generated action potentials, and they formed functional synapses in vitro. Furthermore, the transplantation of iMuSCs or their cell extracts into the muscles of mdx mice (i.e., a mouse model of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy [DMD]) could restore the morphology of their previously damaged neuromuscular junctions (NMJs), suggesting that the beneficial effects of iMuSCs may not be restricted to cell restoration alone, but also due to their transient paracrine actions. The current study reveals the essential role of iMuSCs in the restoration of NMJs related to injuries and diseases.

Introduction

Under normal conditions, skeletal muscle can repair itself by removing damaged myofibers and synthesizing new muscle fibers to restore functional contractile properties1. In line with its regenerative property, skeletal muscle is enriched with stem cells2. The resident satellite cells and muscle stem cells (MuSCs), which are populations of mononucleated cells located between the basal lamina and sarcolemma of muscle fibers, are responsible for the postnatal growth, repair, and maintenance of skeletal muscle3. After necrosis of damaged muscle fibers, an inflammatory response is initiated which leads to the phagocytosis of injured myofibers and the activation of normally quiescent MuSCs4–6. The activated MuSCs proliferate, migrate to the site of injury, fuse, and differentiate to form new myofibers7. In the last few years, researchers have shown that MuSC transplantation is a promising tool for both the repair and regeneration of skeletal muscle tissues. However, their loss of ‘stemness’ during culture, their inability to cross the vessel wall for systemic delivery, and their poor survival after implantation greatly compromise their therapeutic efficacy8, 9.

Recent studies have discovered that skeletal muscles contain a number of heterogeneous cell populations10, 11. Several stem cell-like cells (including MuSCs), various side populations12, muscle progenitor cells13, and putative myoendothelial precursors14 have been identified in skeletal muscle tissues based on their expression of surface markers. These cells displayed multipotency and can differentiate into other lineages, such as ectodermal neuronal cells15. Previous studies have been limited to MuSCs derived from healthy, uninjured muscles. In fact, following muscle injury, the local microenvironment of resident precursor cells become altered16, 17 which can lead to changes in their phenotype and biomolecular characteristics. Our recent studies18 have shown that a unique population of MuSCs, named iMuSCs exist in injured murine skeletal muscle, and can be isolated by using a modified preplate technique19–21 and a Cre-LoxP system that established in our laboratory22. This unique population of iMuSCs expressed several pluripotent and myogenic stem cell markers, such as Oct4 (also called as Pou5fl), Sox2 (SRY-box 2), Nanog, Msx1 (Msh homeobox 1), Sca1 (Stem cell antigen-1), Pax7 (Paired box protein 7), and CD3418. When compared to MuSCs isolated from uninjured muscles, iMuSCs were extremely sensitive to transient microenvironmental changes, had elevated migratory capacity, and had strong myogenic properties both in vitro and in vivo 20. We also found that these iMuSCs were capable of differentiating into non-myogenic related lineages (such as CD31+ endothelial-like cells20) and fulfilled several in vitro and in vivo criteria for multipotency18. These results strongly suggest that the stimulation of injuries can reprogram iMuSCs to a more multipotent state while maintaining their myogenic origin.

Of particular interest is the reported ability of iMuSCs to differentiate into neural lineages in vitro 18. In the current study, we investigated the regenerative potential of iMuSCs with specific focus on neurogenesis. In vitro, we have studied neuronal-like cells developed from iMuSCs, and in vivo, we evaluated the efficiency of iMuSCs in repairing neuromuscular junctions (NMJs) following intramuscular transplantation into mdx mice, a murine model that represents Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD).

Materials and Methods

Animal studies

All animal experiments and related experimental protocols were approved by the Center for Laboratory Animal Medicine and Care at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. The methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. Female C57BL/6J mice and male mdx mice were used in this study (Jackson Lab; Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Muscle injuries were created following previously published protocols20. Briefly, the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle in one leg of each mouse (female, 4–8 weeks-old, C57BL/6J) was lacerated23, and the TA muscle in the other leg of the same donor mouse served as the control uninjured muscle.

Cell isolation and culture

Four days after laceration injury, the modified preplate technique was used to isolate MuSCs from the uninjured TA muscles and iMuSCs from the injured TA muscles of C57BL/6J mice18, 19, 21. By utilizing this technique, different cell populations could be obtained based on their cell adhesion characteristics: fast adhering fibroblast-like cells, myoblasts, and slow adhering MuSCs. iMuSCs were separately cultured in ESGRO Complete PLUS Clonal Grade Medium (Millipore, USA) in 12-well tissue culture plates (Corning, USA) for 3 weeks18. The medium was then replaced with normal muscle growth medium21 and iMuSCs were further cultured and expanded on collagen type IV-coated flasks in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The control MuSCs were cultured at the same time on collagen type IV-coated flasks in normal muscle growth medium in 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

In vitro differentiation via neurosphere formation

Undifferentiated iMuSCs were cultured in suspension in Neural Stem Cell (NSC) medium [Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen, USA) supplemented with 1% Glutamax, 1% B-27 Supplement (Invitrogen, USA), 20 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor, and 0.5% Penicillin/Streptomycin antibiotics; unless otherwise mentioned, all from Gibco (USA)] for 1 week. To induce neurogenic differentiation, neurospheres were plated on collagen type IV/Poly-L-ornithine/Laminin (USA) coated 24-wells plates or on Poly-L-ornithine/Laminin coated glass coverslips and cultured for 21 days in Neural Differentiation (ND3) medium [Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen, USA) supplemented with 1% Glutamax (Gibco, USA), 1% B-27 Supplement (Invitrogen, USA), 20 ng/ml brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Sigma, USA), and 0.5% Penicillin/Streptomycin (Gibco, USA).

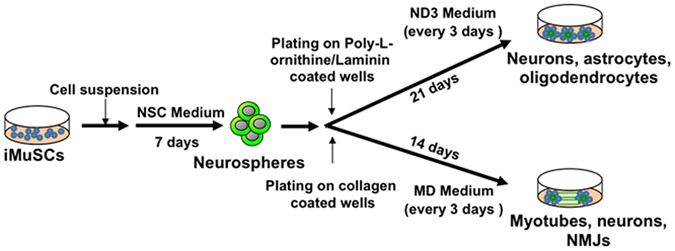

Additionally, for myotube differentiation, neurospheres were plated on collagen type IV coated wells in Muscle Differentiation (MD) medium [DMEM supplemented with 2% horse serum (HS) and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin antibiotics (Gibco, USA) and cultured for 14 days (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

In vitro differentiation protocol. Undifferentiated iMuSCs were cultured in Neural Stem Cell (NSC) Medium in suspension for 7 days to induce neurosphere formation. For myotube differentiation, neurospheres were plated on collagen-coated wells in Muscle Differentiation (MD) Medium. For neural differentiation, neurospheres were plated on laminin/poly-L-ornithine coated wells and cultured for 21 days in Neural Differentiation (ND3) Medium.

Immunocytochemistry

Samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, USA) and were then permeabilized for 30 minutes with 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma, USA). Nonspecific binding of antibodies was blocked with 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 5% HS (Sigma, USA) for 1 hour. The primary antibodies were applied overnight at 4 °C then incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with the appropriate fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibodies (Suppl. Table 1). The nuclei were visualized using 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining (Sigma, USA) and fluorescent microscopy (Nicon). The resulting images were quantitatively analyzed using ImageJ Software (National Institutes of Health, USA).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA from the MuSCs, iMuSCs, and the neuronal differentiating iMuSCs were isolated using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, USA). Total RNA from the biopsied TA tissues was isolated using the RNeasy Microarray Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen, USA). cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of RNA via iScriptTM cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions. Gene expression was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) using MyiQ real-time PCR (Bio-Rad, USA). The applied primers were designed by Oligo software (Suppl. Table 2) (Oligo Perfect Designer, Invitrogen, USA). Reactions were measured in duplicate using custom 2x Syber Green Master Mix based on the hot-start Jumpstart Taq DNA Polymerase enzyme (Sigma). The amplification was done for 40 cycles (95 °C 20 sec, 60 °C 20 sec, 72 °C 40 sec). To verify the PCR product, melting curves were carried out in each reaction. Relative quantification of mRNA was determined by the ΔΔCt method (2−ΔΔCt formula)24 using the expression profile of the corresponding control samples as reference.

Whole-cell patch-clamp recording

Electrophysiological recordings were performed in whole-cell recording configuration under voltage and current-clamp mode. Patch pipettes were pulled from glass capillaries with an outer diameter of 1.5 mm on a Micropipette Puller (P-97, Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA, USA). The resistance between the recording electrode filled with pipette solution and the reference electrode was 4–6 MΩ. Membrane current and voltage signals were measured using a patch-clamp amplifier (Axon 700B, Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), were sampled using a Digidata 1440 interface connected to a personal computer, and were analyzed with Clampex and Clampfit software (Version 10.3, Axon Instruments). In most experiments, 70% series resistance was compensated. The membrane potential was held at −70 mV during voltage-clamp mode. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (22–25 °C).

The standard external solution contained (in mM) 150 NaCl, 5KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid). The pH was adjusted to 7.4 with Tris base. The osmolality of the solutions was adjusted to 310–320 mOsm/L with sucrose and a microosmometer (Advanced Instruments, Inc., Norwood, MA, USA; Model 3300). The pipette solution for whole-cell patch-clamp recording contained (in mM) 90K+-gluconate, 40 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 NaCl, 10 EGTA (ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid), 4 Mg-ATP, and 10 HEPES/KOH (pH 7.4). Whole-cell recordings were obtained from neuronal differentiated iMuSCs at day 21. The protocol for voltage clamp recording of Na+ channels was as follows: cells were hyperpolarized to −90 mV, stepped to a defined voltage as indicated, and returned to −70 mV before the next cycle was run (with a different voltage step). Each cycle took 120 ms. For K+ current recording, current-voltage (I-V) relationships of membrane currents were recorded using a ramp protocol (−100 to +50 mV). Na+ and K+ currents were blocked by tetrodotoxin (1 µM) and tetraethylammonium (5 mM) separately. In the current clamp, action potentials were generated by current injections of increasing magnitude with a duration of 600 ms (10 pA steps, from −20 pA to +90 pA). Spontaneous action potentials were also recorded in current clamp mode (0 pA).

Transplantation of iMuSCs into mdx mice

Both control MuSCs and iMuSCs were pre-labeled with GFP (1 × 106 cells diluted in 10 μL PBS) and were separately injected into the left and right gastrocnemius (GM) muscles of five 6- to 8-week-old male mdx mice. Additionally, in other experiments, cell extracts prepared from iMuSCs and MuSCs were separately injected into the left and right GM muscles of five 6- to 8-week-old mdx mice. iMuSCs, MuSCs, and PBS-treated GM tissues were harvested from each mouse for histological and qPCR analysis both 1 and 3 weeks after transplantation.

Assessment of NMJ morphology

Harvested muscle tissues were mounted and frozen in cooled 2-methylbutane immersed in liquid nitrogen. Each muscle sample was cryosectioned to a thickness of 30 μm, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and permeabilized. Nonspecific binding of antibodies was blocked with 10% HS, and Alexa-594 conjugated α bungarotoxin (Btx) (diluted 1:1000 in 10% HS/PBS) was applied for 1 hour at room temperature. Results were visualized by Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscopy.

Data processing and statistical analyses

A minimum of five biological replicates was established for each of the described experiments. qPCR expression data was analyzed by MyiQ qPCR software (Bio-Rad, USA). The Ct values were exported and used as raw data for analysis of qPCR data. Data normalization was calculated using endogenous control β-actin and GAPDH, and fold changes were determined by the ΔΔCt method (2−ΔΔCt)24 by using the expression profile of the corresponding control as reference. Statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism version 6.0 (Graph Pad Software, Inc, USA). All numerical data were expressed as mean values ± SD. Comparisons between two groups were performed by using Student’s t-test assuming two-tailed distribution, and unequal variances. For multiple comparisons, ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis test was applied. Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

In order to account for the depth of NMJs during the assessment of NMJ morphology, a maximum intensity flat plane projection was made from Z-stacked images using the ImageJ software. Only NMJs in a complete “en face view” was selected for further analysis. After corrections were made to account for background noise, binary images were created, skeletonized, and histograms describing the connectivity for each pixel were generated. The number of segments described the density of NMJs and the means of terminal and branching nodes were also calculated by the Amira software (Fei, USA). At least 15 images were blindly selected and analyzed and five biological replicates were used for the study. The number of clusters within individual NMJs was counted using unprocessed images.

Results

Neurosphere, myotube, and NMJ formation of iMuSCs

With our successful cell isolation method15, 20, 22, iMuSCs were isolated from the slow adhering CD34+/Sca1+ fraction from the injured murine TA muscles and expanded in culture in muscle growth medium. As we have previously reported18, two weeks after cell isolation, proliferating iMuSCs (~0.1% of the entire muscle cell population) appeared in the culture dishes in the ESGRO Complete PLUS Clonal Grade Medium; however, no such cells were detected in the cultures established from control, uninjured muscles18.

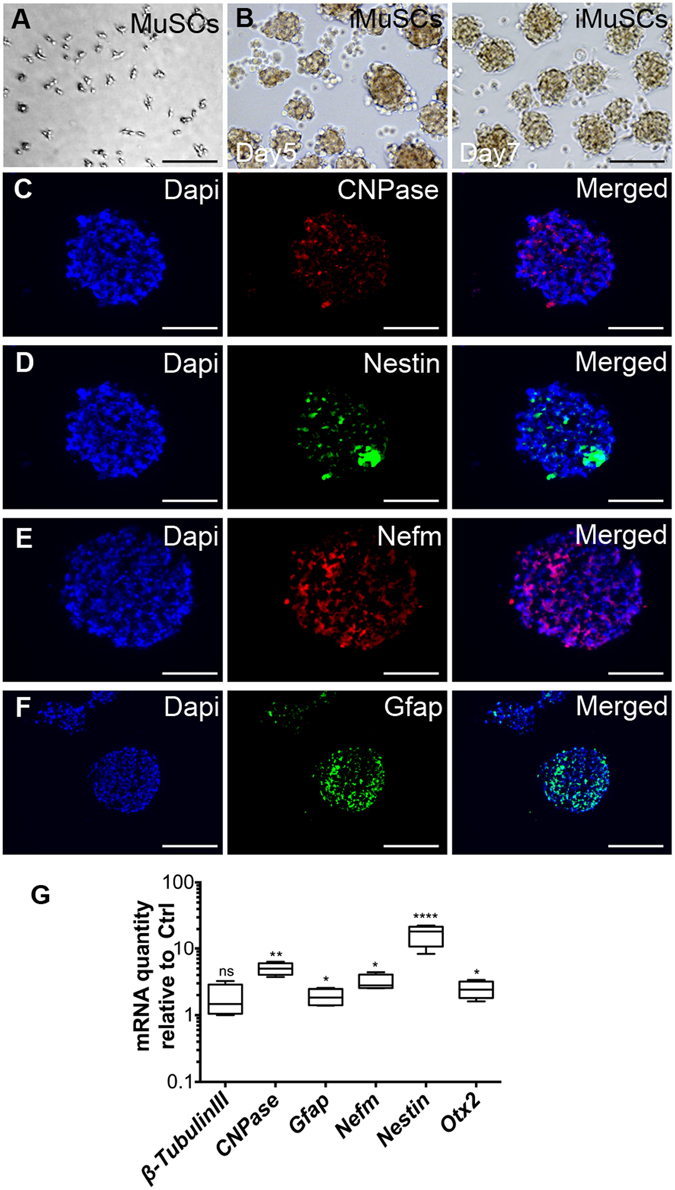

For neuronal differentiation, undifferentiated iMuSCs were transferred as single cells into NSC medium and cultured for 1 week. Within this time, iMuSCs formed neurosphere-like structures floating in suspension (Fig. 2B), while the control MuSCs showed no sign of forming these structures (Fig. 2A). These spheres stained positive for the early neuronal progenitor/stem cell marker Nestin (Fig. 2D), and for some further differentiated neural phenotypes such as oligodendrocytes by (i.e., 2′,3′-cyclic-nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase [CNPase] (Fig. 2C), neurons for by the neuronal cytoskeleton marker Neurofilament-M (Nefm) (Fig. 2E), and astrocytes by glial fibrillary acidic protein (Gfap) (Fig. 2F). Gene expression profiles of the iMuSCs-induced neurospheres were also analyzed by qPCR. As confirmation of the immunocytochemistry results, neuronal and neuronal progenitor/stem cell markers, such as Nestin, Nefm and β-Tubulin III, and other lineage markers (i.e., CNPase, Gfap, and Orthodenticle homeobox 2 [Otx2]) were highly overexpressed in the iMuSC-formed neurospheres compared to the undifferentiated iMuSCs (Fig. 2G).

Figure 2.

Neurosphere formation of iMuSCs. (A) BF image of the control MuSCs that could not form neurospheres. (B) BF image of the iMuSC-formed neurospheres in suspension. (C–F) Immunofluorescence images of cryosectioned neurospheres after 7 days of culture. They stained positive for CNPase (red, C), Nestin (green, D), Nefm (red, E), and Gfap (green, F). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 100 µm. (F) Whisker plots summarize the gene expression profiles of five biological replicates of iMuSC-formed neurospheres after 7 days of culture compared to undifferentiated iMuSCs by qPCR.

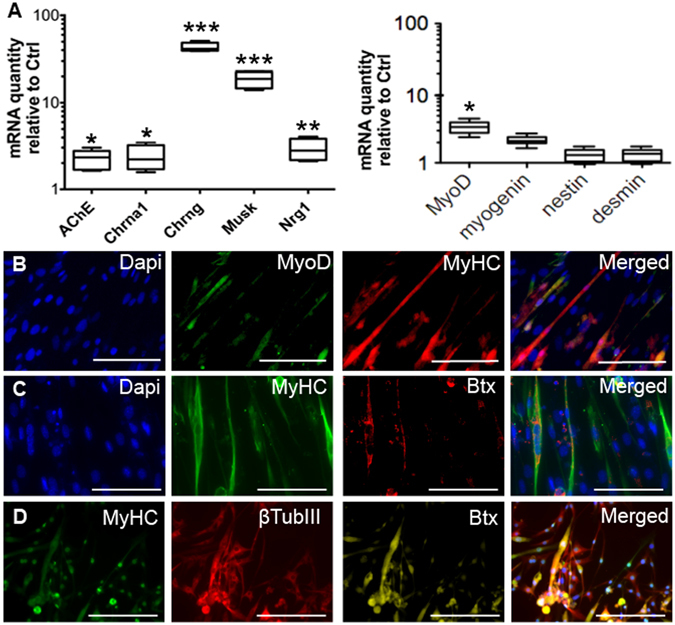

The iMuSC-formed neurospheres were harvested and plated in collagen type IV/poly-L-ornithine/laminin coated 24-well tissue culture plates (Corning, 2–3 neurospheres/well) in MD medium in 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 14 days. In these conditions, iMuSC-formed neurospheres proliferated to near-confluence and aligned in preparation for fusion, and extensive myotube formation was observed with MyoD and Myosin heavy chain (MyHC) expression (Fig. 3B–D, and Suppl. Movie). Interestingly, the attached neurospheres also formed neuron-like structures, expressing β-Tubulin III (Fig. 3D). The presence of formed NMJs was demonstrated by α Bungarotoxin (Btx) staining (Fig. 3C,D). In addition, several NMJ-related genes were overexpressed, but myogenic genes were expressed in a low level in the culture as demonstrated by qPCR analysis in these neurospheres, including genes with NMJs: acetylcholinesterase (AChE), cholinergic receptors (nicotinic, alpha 1 [Chrna1], and gamma [Chrng], muscle-specific kinase (MuSK), neuregulin 1 (Nrg1), and myogenic genes: MyoD, and Myogenin (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Myogenic differentiation of iMuSCs and NMJ formation. (A) Whisker plots summarize the expression of NMJ-related genes as well as the myogenic genes within the neurosepheres in culture, analyzed by qPCR. (B) After the neurospheres were replaced into monolayer culture in MD Medium, their recovered their myogenic ability, formed myotube-like structures, and begun expression of myogenic protein MyoD (green, B), MyHC (Red, B; green, C,D). The attached neurospheres also formed neuron-like structures expressing β-Tubulin III (red, D). The presence of NMJs was shown by Btx staining (red, C; yellow, D). Nuclei were stained with Dapi. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Monolayer differentiation of iMuSCs along the neuronal pathway

We tested several culture conditions to induce neuronal differentiation of iMuSCs. In our laboratory, the attachment of the neurospheres and the appearance of cells with neuronal morphology were limited and the plated cells did not survive more than 1 week using previously published protocols. In order to improve the attachment and neuronal differentiation of iMuSCs, we tested 2 additional media (Suppl. Table 3). The percentages of attached iMuSC-induced neurospheres on day 7 after plating were 17% in ND1 media, 75% in ND2 media, and 92% in ND3 media. For further experiments, we used the ND3 medium in which the attached neurospheres could mature and form neuron-like structures on collagen type IV/polyornithine/laminin coated plates.

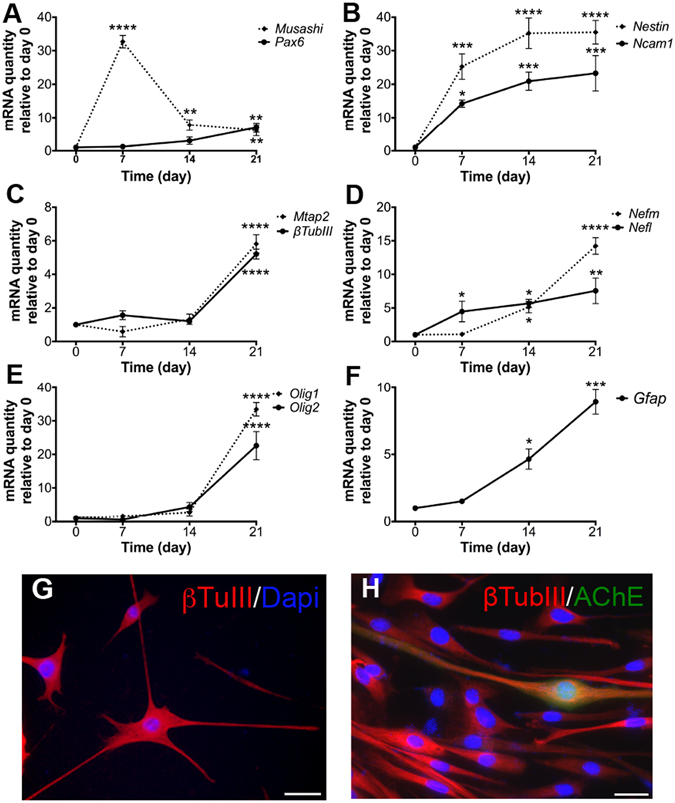

Real-time PCR experiments confirmed the appearance of cells expressing neuronal marker genes and revealed gene expression kinetics during neuronal precursor differentiation of iMuSCs (Fig. 4). The expression of each gene was analyzed in samples from undifferentiated iMuSCs (day 0) as well as from days 7, 14, and 21. There were no statistically significant differences in the expression of the housekeeping gene Gapdh between the different time points of sampling (P > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Induced neuronal differentiation of iMuSCs. (A–F) Gene expression kinetics were analyzed by qPCR during the 21-day neuronal differentiation period of the plated iMuSC-formed neurospheres. Data are presented as ± SEM of five biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. (G,H) Immunocytochemical staining of neurons after 21-day differentiation from iMuSC-formed neurospheres. β-Tubulin III (red, G,H) and AChE (green, H). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar = 100 µm (G) and 10 µm (H).

The Musashi RNA-binding protein 1, the adhesion molecule Ncam1, the intermediate filament Nestin, and the transcription factor Pax6 are expressed in neuronal precursors in neuroepithelium in vivo 25–27. Musashi1 (Fig. 4A) was strongly upregulated (32.7 ± 3 fold) on day 7 of differentiation. During the neuronal maturation process, Musashi expression was downregulated (6.1 ± 2 fold) on day 21. A significant (8.4 ± 1 fold) upregulation of Pax6 (Fig. 4A) mRNA expression was demonstrated on day 21. This upregulation was initiated already on day 7 (1.2 ± 0.5 fold), although it was not statistically significant at this time point (P > 0.05). Nestin (Fig. 4B) mRNA expression was increased already from day 7 (25.3 ± 3 fold) and stayed at a plateau (35.2 ± 2 fold) for the later time points investigated. Ncam1 (Fig. 4B) mRNA expression continuously increased during the 21 days of differentiation and was significantly different to control levels at day 7 (14.2 ± 2 fold), 14 (20.9 ± 3 fold) and 21 (23.3 ± 4 fold). Microtubule-associated protein Mtap2, β-Tubulin III, Nefm and Nefl are neuronal cytoskeletal proteins expressed in mature neurons28–30. Expression of mRNA for Mtap2 and β-Tubulin III (Fig. 4C) was upregulated on day 21 of differentiation, showing 5.8 ± 1 and 5.2 ± 0.5 fold increase, respectively. Neither Mtap2 nor β-Tubulin III mRNA expression was significantly changed (P > 0.05) on days 7 and 14 as compared to undifferentiated iMuSCs (day 0). Expression of mRNA for Nefm and Nefl (Fig. 4D) was showing a continuous upregulation from day 7 on, with 2.1 ± 0.3 and 4.9 ± 0.5 fold, reaching a 7.2 ± 06 and 14.5 ± 1 fold increase at day 21. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors, oligodendrocyte transcription factor 1 (Olig1) and Olig 2 are early oligodendrocyte progenitors that are coordinately expressed in the developing central nervous system and postnatal brain determining oligodendrocyte differentiation in vivo 31. A strong upregulation of Olig1 (33.4 ± 2 fold) and Olig2 (22.6 ± 3 fold) mRNA expression level was shown on day 21 of differentiation (Fig. 4E). The upregulation seemed initiated on day 14 (2.7 ± 1 fold), although it was not statistically significant. Gfap is an intermediate filament protein that is expressed mainly by astrocytes in the central nervous system32. Expression of mRNA for Gfap was upregulated at days 14 and 21 of differentiation, showing 6.6 ± 1 and 8.9 ± 1 fold increase compared to undifferentiated iMuSCs (Fig. 4F).

Immunocytochemical analysis supported the qPCR data on neuronal marker expression. Neuronal precursor differentiation resulted in appearance of mature, elongated cells on day 21 which expressed antigens for antibodies against the neuronal cytoskeletal proteins β-Tubulin III (Fig. 4G,H) and AChE (Fig. 4H).

Mature and functional neuronal development of iMuSCs in vitro

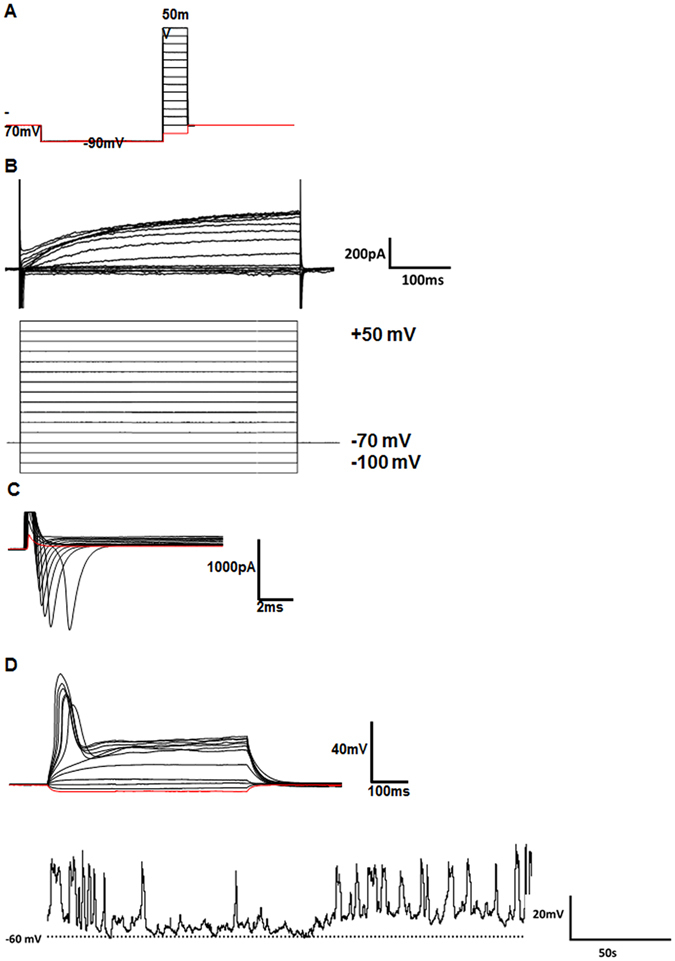

The electrophysiological properties of neurons from at least three independent differentiation passes were evaluated using voltage- and current-clamp recordings. iMuSC-induced neurospheres were differentiated on Poly-L-ornithine/Laminin coated glass coverslips towards the neuronal lineage for 21 days and then placed into a recording chamber for whole-cell patch-clamp studies. Differentiation into mature, electrophysiologically active neurons was shown by the presence of voltage-dependent Na+ and K+ currents and spontaneous action potentials in individual patch-clamped neurons (Fig. 5). Thus, our differentiation protocol yielded bona fide neurons from iMuSCs.

Figure 5.

Electrophysiological evidence for successful neuronal development. (A) Whole-cell voltage clamp recording protocol used for patch-clamp analysis. (B) Representative example for K+ currents observed during 500 ms voltage steps of the whole-cell voltage clamp recording protocol displayed in (A). (C) Representative example of Na+ currents observed during 20-ms voltage steps of the whole-cell voltage clamp recording protocol displayed in (A). Note that Na+ currents (downward deflections) were observed at voltages ≤−30 mV. (D) Individual traces of action potential-like events generated by an intracellular current injection protocol. Spontaneous action potential-like events were recorded in current-clamp mode (0 pA). The dashed line indicates the −60 mV resting membrane potential.

Improved NMJ morphology by transplanted iMuSCs or iMuSC extracts in mdx mice

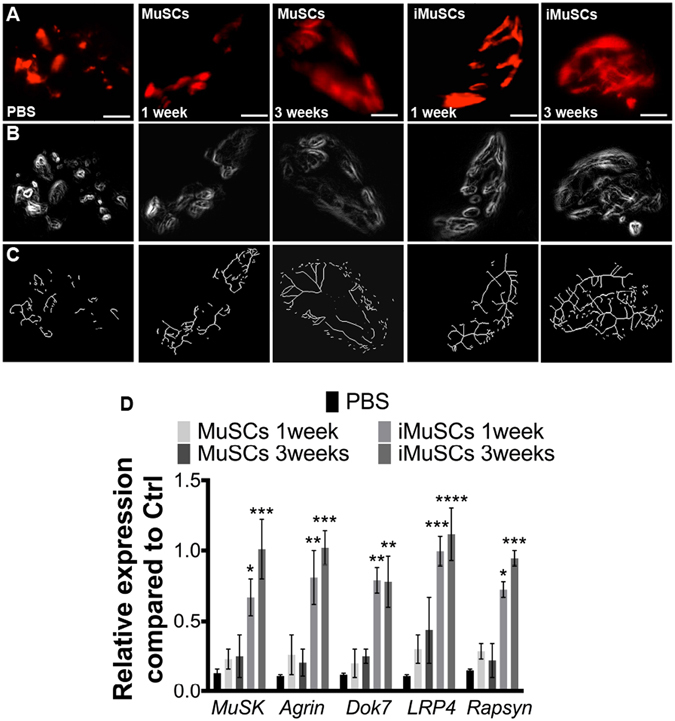

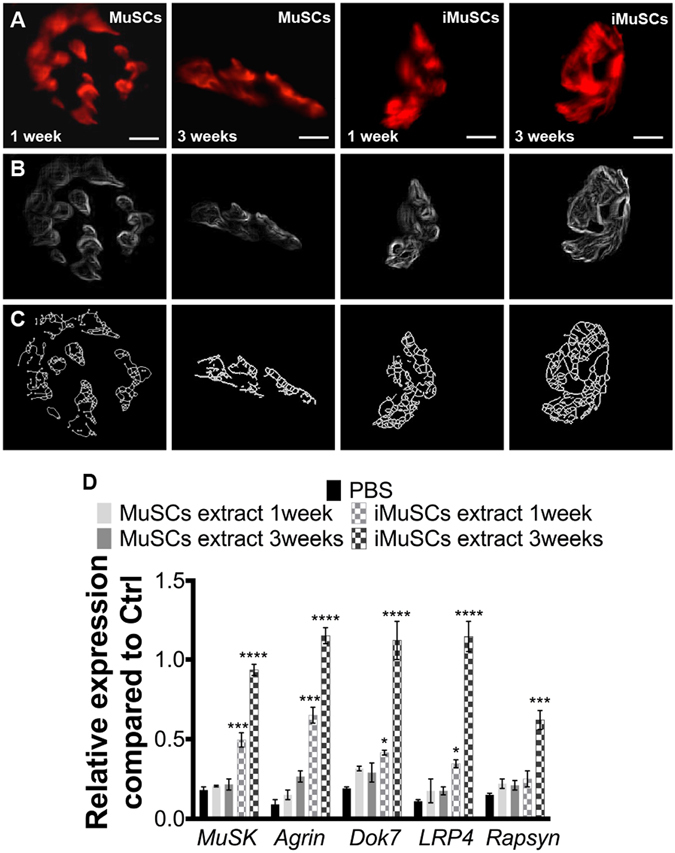

Since the iMuSC-formed neurospheres displayed heterogeneous phenotypes, they were not suitable for cell therapy applications. Therefore, undifferentiated iMuSCs and control MuSCs were separately injected into the left and right GM muscles of mdx mice. Mdx muscle treated with control PBS and MuSCs showed a non-continuous, punctate pattern of NMJ morphology; however, the NMJ morphology was markedly improved in the iMuSC-treated muscles (Fig. 6A–C), and also in the iMuSC extract-treated muscles (Fig. 7A–C). These morphological changes were quantified by the number of segments and the means of terminal and branching nodes (Suppl. Table 4). Based on these data, the acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) in mdx mice were discontinuous and punctate, consistent with previous findings in recent literature33, 34. However, after iMuSC transplantation, AChRs in mdx mice showed a significantly improved morphology as evidenced by more dense aggregates, increased continuity and greater number of segments, and the presence of terminal nodes and branching nodes. These differences indicate a transient improvement in AChRs density due to the transplantation of iMuSCs and iMuSC -extracts into the muscle tissues of mdx mice.

Figure 6.

NMJ recovery after transplantion of iMuSCs into mdx mice. (A) Representative IF images of NMJs after treatment of GMs with no cells, MuSCs, and iMuSCs in mdx mice (red, A). (B) Processed binary images and (C) skeletonized images show discontinuity and branching patters. (D) Expression of MuSK complex constituents. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of five biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Figure 7.

NMJ recovery after injection of iMuSC extracts into mdx mice. (A) Representative IF images of NMJs after injection with MuSC and iMuSC extracts into the GMs of mdx mice (red, A). (B) Processed binary images and (C) skeletonized images show discontinuity and branching patters. (D) Expression of MuSK complex constituents. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of five biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Muscle-specific kinase (MuSK) is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase crucial for forming and maintaining the NMJs; activation of the MuSK complex drives AChR clustering35, 36. It has been previously shown that expression of the MuSK complex is altered in mdx mice37. Transcripts for the multiprotein MuSK signaling complex (Agrin, LRP4, Dok7, MuSK and Rapsyin) were obtained from five 6–8 week-old male wild-type C57BL/6J mice and five 6–8-week-old male control, and MuSCs and iMuSCs (along with their respective extracts) -injected mdx mice were analyzed by qPCR (Figs 6D and 7D). Gene expression levels were compared to the control wild-type C57BL/6J mice. Interestingly, in contrast to previously-published results37, we found that the levels of mRNA expression for each constituent of the MuSK complex was significantly decreased in the mdx mice and their expression was markedly improved 3 weeks after the injection of iMuSCs and iMuSC extract.

Discussion

Complex biological processes occur following skeletal muscle injury and repair. Several time-dependent phases are interrelated with healing, including muscle degeneration/necrosis, inflammation/immune responses, stem cell activation, tissue regeneration/remodeling, and functional repair with the deposition of fibrous scar tissue38, 39. Functional repair includes the complete reinnervation and revascularization in the regenerated muscle fibers. Although the process of identifying innervation is challenging, due to difficulties in tracking the appropriate biomarkers, newly formed NMJs between the surviving axons and the regenerated muscle fibers have been identified 2 weeks after skeletal muscle injury40. Previous reports have indicated that MuSCs could also give rise to neuronal-like cells, based on the expression of the neuron-associated genes or proteins15, 41, suggesting that muscle stem cells could potentially differentiate into the lineage of neighboring cells. These studies discuss the multipotency or transdifferentiation potential of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs); however, this turned out to be due mostly to in vitro assays reflecting the potential of the culture medium rather than the potential of the cells42–44. Thus, in vivo cell implantation studies are extremely important to prove the concept of the multipotent differentiation ability of iMuSCs.

We are not aware of any other published reports that demonstrate the existence of a side population of stem cells within injured skeletal muscle tissue that can differentiate into functional neurons in vitro and improve NMJs formation in vivo. Our qPCR results following iMuSC neuronal differentiation provide detailed information on gene expression kinetics for this unique stem cell population. Expression of mRNA markers for neuronal precursors (Musashi, Ncam1, Nestin, and Pax6) and for mature neurons (Mtap2, β-Tubulin III, Nefm, and Nefl) were increased throughout the process of neuronal differentiation; several of these markers were significantly upregulated (e.g. Pax6, Ncam1, Nefm, and Mtap2). The sequence of neuronal differentiation events (such as the formation of neuronal precursors and their further maturation,) was reflected in their mRNA expression profiles and followed similar patterns and temporal windows as those that took place during neurogenesis. Additionally, our differentiation protocol gave rise to a small population of oligodendrocytes and astrocytes as evidenced by the upregulated mRNA expression of Olig1, Olig2, and Gfap. Our immunocytochemical analyses supported this qPCR data by demonstrating the presence of β-Tubulin III, Nefm, and AChE. To confirm the successful neuronal differentiation of iMuSCs, whole-cell patch-clamp studies demonstrated the presence of voltage-dependent Na+ and K+ currents and spontaneous action potentials within individual patch-clamped neurons. Although these electrophysiological findings may not have represented the entire culture, our data from iMuSC-differentiated neurons were qualitatively similar to previously published functional data obtained from neurons generated from mouse embryonic stem cells45, 46. Altogether, these data suggest the appearance of mature and functional neuronal-like cells derived from the differentiation of iMuSCs.

We selected a DMD mouse model to investigate the processes of NMJ formation and function. DMD is a relatively common X-linked neurodegenerative disorder in which progressive muscle degeneration, weakness, increased susceptibility to muscle injury, and inadequate repair underlie its pathologic features; the disorder affects approximately 1 in 3,200 male infants worldwide47, 48. In normal mammalian muscle, AChRs densely cluster in winding, band-like arrays on post-synaptic membranes49. These bands most often form a continuous structure commonly referred to as having a “pretzel-shape”. To achieve maximally efficient neurotransmission, pre- and post-synaptic membranes exhibit the same band pattern. In patients with DMD, however, this “pretzel-shape” is fragmented into many individual gutters49–51. The causes and molecular events resulting in fragmentation of the NMJs in DMD patients is still unclear. Although current published studies agree that the primary defect of DMD is confined to the stability of the muscle cell membrane52, a detailed understanding the biomolecular sequences leading to NMJ dysfunction and its contribution to the functional deficits observed in DMD could revolutionize the treatment of many types of musculoskeletal conditions.

Multifunctional signaling complexes are involved in the organization of NMJs35. MuSK is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase crucial for forming and maintaining the NMJs36. Activation of the MuSK complex drives AChR clustering. Based on the fact that mutations of MuSK complex are responsible for diseases involving the NMJ, it would be interesting to determine whether the upregulation of MuSK in dystrophic muscle would rescue the deterioration of its NMJs. Our results confirmed that NMJ morphology was transformed in the muscles of mdx mice and that the levels of MuSK-related gene expression were also altered. These results contrast those of a previous study in which decreased MuSK-related mRNA levels represented the only significant differences between wild-type and mdx muscles; the levels of mRNA expression of Agrin, LRP4, Dok7, and Rapsyn were not changed37. Furthermore, in order to verify the neurogenic potential of iMuSCs, we transplanted undifferentiated iMuSCs or iMuSCs extracts into the GM muscles of mdx mice. Three weeks after the transplantation, we observed significant improvements in NMJs morphology (i.e., more dense aggregates, increased continuity, greater numbers of segments, and the presence of terminal and branching nodes), which corroborated with the increased mRNA expression level of the MuSK complex when compared to the control MuSCs, indicating the essential role of iMuSCs in improving NMJs in dystrophic muscle.

In summary, iMuSCs isolated from the injured murine skeletal muscles has a remarkable efficiency to form mature and functional neurons and has significant benefits to the restoration of NMJ function within those injured or diseased skeletal muscles in vivo. According to our results, we hypothesize that the observed beneficial effects of intramuscular iMuSC transplantation are due in large part to the variety of growth factors, chemokines, cytokines, immunosuppressive molecules, among many other factors secreted in physiologic ratios by iMuSCs at the site of injury. In future studies, elucidating the roles iMuSCs-derived biomolecules for tissue regeneration may provide insight into the development of alternative therapies that can overcome current cell sourcing issues, especially in the treatment of neuromuscular conditions.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. M. Zhengmei for her continuous help and advice during immunocytochemical analyses, and Dr. L. Rajagopalan for editorial assistance. We also acknowledge a travel award for K.V. to present this work at a meeting of The American Society for Neural Therapy and Repair (ASNTR), April 24–26, 2014, Tampa, Florida, USA.

Author Contributions

K.V. was responsible for the conception and design, experimental work, collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, and writing the manuscript; H.P. and X.D., assisted with the experimental work, collection and/or assembly of data; H.S., assisted with whole-cell patch-clamp recording and writing the manuscript; Q.T and R.D., assisted with data analysis and interpretation; J.H., assisted with interpretation and writing of the manuscript; Y.L., designed the project, supervised all experiment, data analysis and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01311-4

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Huard J, Li Y, Fu FH. Muscle injuries and repair: current trends in research. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2002;84-A:822–832. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200205000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yin H, Price F, Rudnicki MA. Satellite cells and the muscle stem cell niche. Physiological reviews. 2013;93:23–67. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buckingham M, Montarras D. Skeletal muscle stem cells. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:330–336. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tidball JG. Inflammatory cell response to acute muscle injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:1022–1032. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199507000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shen W, Li Y, Zhu J, Schwendener R, Huard J. Interaction between macrophages, TGF-beta1, and the COX-2 pathway during the inflammatory phase of skeletal muscle healing after injury. J Cell Physiol. 2008;214:405–412. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shen W, Prisk V, Li Y, Foster W, Huard J. Inhibited skeletal muscle healing in cyclooxygenase-2 gene-deficient mice: the role of PGE2 and PGF2alpha. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:1215–1221. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01331.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tedesco FS, Dellavalle A, Diaz-Manera J, Messina G, Cossu G. Repairing skeletal muscle: regenerative potential of skeletal muscle stem cells. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:11–19. doi: 10.1172/JCI40373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodgerson DO, Harris AG. A comparison of stem cells for therapeutic use. Stem Cell Rev. 2011;7:782–796. doi: 10.1007/s12015-011-9241-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunt KR, Weisel RD, Li RK. Stem cells and regenerative medicine - future perspectives. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2012;90:327–335. doi: 10.1139/y2012-007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ceafalan LC, Popescu BO, Hinescu ME. Cellular players in skeletal muscle regeneration. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:957014–21. doi: 10.1155/2014/957014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Relaix F, Zammit PS. Satellite cells are essential for skeletal muscle regeneration: the cell on the edge returns centre stage. Development. 2012;139:2845–2856. doi: 10.1242/dev.069088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gussoni E, et al. Dystrophin expression in the mdx mouse restored by stem cell transplantation. Nature. 1999;401:390–394. doi: 10.1038/43919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qu-Petersen Z, et al. Identification of a novel population of muscle stem cells in mice: potential for muscle regeneration. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:851–864. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamaki T, et al. Identification of myogenic-endothelial progenitor cells in the interstitial spaces of skeletal muscle. The Journal of cell biology. 2002;157:571–577. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arsic N, Mamaeva D, Lamb NJ, Fernandez A. Muscle-derived stem cells isolated as non-adherent population give rise to cardiac, skeletal muscle and neural lineages. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:1266–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mu X, Li Y. Conditional TGF-beta1 treatment increases stem cell-like cell population in myoblasts. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:679–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polesskaya A, Seale P, Rudnicki MA. Wnt signaling induces the myogenic specification of resident CD45+ adult stem cells during muscle regeneration. Cell. 2003;113:841–852. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00437-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vojnits K, Pan H, Mu X, Li Y. Characterization of an Injury Induced Population of Muscle-Derived Stem Cell-Like Cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17355. doi: 10.1038/srep17355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, Y., Pan, H. & Huard, J. Isolating stem cells from soft musculoskeletal tissues. Journal of visualized experiments: JoVE (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Mu X, et al. Slow-adhering stem cells derived from injured skeletal muscle have improved regenerative capacity. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:931–941. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gharaibeh B, et al. Isolation of a slowly adhering cell fraction containing stem cells from murine skeletal muscle by the preplate technique. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1501–1509. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mu X, Peng H, Pan H, Huard J, Li Y. Study of muscle cell dedifferentiation after skeletal muscle injury of mice with a Cre-Lox system. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bedair H, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-1 therapy improves muscle healing. Journal of applied physiology. 2007;102:2338–2345. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00670.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simpson TI, Price DJ. Pax6; a pleiotropic player in development. BioEssays: news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 2002;24:1041–1051. doi: 10.1002/bies.10174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen L, Rigo JM, Malgrange B, Moonen G, Belachew S. Untangling the functional potential of PSA-NCAM-expressing cells in CNS development and brain repair strategies. Current medicinal chemistry. 2003;10:2185–2196. doi: 10.2174/0929867033456774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiese C, et al. Nestin expression–a property of multi-lineage progenitor cells? Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS. 2004;61:2510–2522. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carden MJ, Trojanowski JQ, Schlaepfer WW, Lee VM. Two-stage expression of neurofilament polypeptides during rat neurogenesis with early establishment of adult phosphorylation patterns. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1987;7:3489–3504. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-11-03489.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matus A. Microtubule-associated proteins and neuronal morphogenesis. Journal of cell science. Supplement. 1991;15:61–67. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1991.Supplement_15.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katsetos, C. D., Legido, A., Perentes, E. & Mork, S. J. Class III beta-tubulin isotype: a key cytoskeletal protein at the crossroads of developmental neurobiology and tumor neuropathology. Journal of child neurology18, 851–866, discussion 867 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Hack MA, Sugimori M, Lundberg C, Nakafuku M, Gotz M. Regionalization and fate specification in neurospheres: the role of Olig2 and Pax6. Molecular and cellular neurosciences. 2004;25:664–678. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, et al. Downregulation of Pax3 expression correlates with acquired GFAP expression during NSC differentiation towards astrocytes. FEBS letters. 2011;585:1014–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marques MJ, Taniguti AP, Minatel E, Neto HS. Nerve terminal contributes to acetylcholine receptor organization at the dystrophic neuromuscular junction of mdx mice. Anatomical record. 2007;290:181–187. doi: 10.1002/ar.20421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyons PR, Slater CR. Structure and function of the neuromuscular junction in young adult mdx mice. Journal of neurocytology. 1991;20:969–981. doi: 10.1007/BF01187915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghazanfari N, et al. Muscle specific kinase: organiser of synaptic membrane domains. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2011;43:295–298. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hesser BA, Henschel O, Witzemann V. Synapse disassembly and formation of new synapses in postnatal muscle upon conditional inactivation of MuSK. Molecular and cellular neurosciences. 2006;31:470–480. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pratt SJ, et al. Recovery of altered neuromuscular junction morphology and muscle function in mdx mice after injury. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS. 2015;72:153–164. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1663-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Charge SB, Rudnicki MA. Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. Physiological reviews. 2004;84:209–238. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goulding M, Lumsden A, Paquette AJ. Regulation of Pax-3 expression in the dermomyotome and its role in muscle development. Development. 1994;120:957–971. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Musaro A. The basis of muscle regeneration. Advances in Biology. 2014;2014:16–16. doi: 10.1155/2014/612471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lavasani M, et al. Human muscle-derived stem/progenitor cells promote functional murine peripheral nerve regeneration. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124:1745–1756. doi: 10.1172/JCI44071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sacchetti B, et al. No Identical “Mesenchymal Stem Cells” at Different Times and Sites: Human Committed Progenitors of Distinct Origin and Differentiation Potential Are Incorporated as Adventitial Cells in Microvessels. Stem Cell Reports. 2016;6:897–913. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhaskaran M, et al. Trans-differentiation of alveolar epithelial type II cells to type I cells involves autocrine signaling by transforming growth factor beta 1 through the Smad pathway. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3968–3976. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609060200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi MY, et al. The isolation and in situ identification of MSCs residing in loose connective tissues using a niche-preserving organ culture system. Biomaterials. 2012;33:4469–4479. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strubing C, et al. Differentiation of pluripotent embryonic stem cells into the neuronal lineage in vitro gives rise to mature inhibitory and excitatory neurons. Mechanisms of development. 1995;53:275–287. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee SH, Lumelsky N, Studer L, Auerbach JM, McKay RD. Efficient generation of midbrain and hindbrain neurons from mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:675–679. doi: 10.1038/76536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bushby K, et al. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and pharmacological and psychosocial management. The Lancet. Neurology. 2010;9:77–93. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bushby K, et al. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: implementation of multidisciplinary care. The Lancet. Neurology. 2010;9:177–189. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rudolf R, Khan MM, Labeit S, Deschenes MR. Degeneration of neuromuscular junction in age and dystrophy. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2014;6:99. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Segalat L, Anderson JE. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: stalled at the junction? European journal of human genetics: EJHG. 2005;13:4–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sieck DC, et al. Structure-activity relationships in rodent diaphragm muscle fibers vs. neuromuscular junctions. Respiratory physiology & neurobiology. 2012;180:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guiraud S, et al. The Pathogenesis and Therapy of Muscular Dystrophies. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2015;16:281–308. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-090314-025003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.