Abstract

The clinical resistance of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) has been linked to EGFR T790M resistance mutations or MET amplifications. Additional mechanisms underlying EGFR-TKI drug resistance remain unclear. The present study demonstrated that icotinib significantly inhibited the proliferation and increased the apoptosis rate of HCC827 cells; the cellular mRNA and protein expression levels of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) were also significantly downregulated. To investigate the effect of PTEN expression levels on the sensitivity of HCC827 cells to icotinib, PTEN expression was silenced using a PTEN-specific small interfering RNA. The current study identified that the downregulation of PTEN expression levels may promote cellular proliferation in addition to decreasing the apoptosis of HCC827 cells, and may reduce the sensitivity of HCC827 cells to icotinib. These results suggested that reduced PTEN expression levels were associated with the decreased sensitivity of HCC827 cells to icotinib. Furthermore, PTEN expression levels may be a useful marker for predicting icotinib resistance and elucidating the resistance mechanisms underlying EGFR-mutated NSCLC.

Keywords: non-small cell lung cancer, HCC827 cells, icotinib, phosphatase and tensin homolog, small interfering RNA

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors with the highest morbidity and mortality, and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for >80% of the recorded cases (1). Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), including gefitinib, are tumor molecular-targeted agents, which have become an important therapeutic strategy for NSCLC (2). Icotinib hydrochloride (icotinib) was developed in China, and is a highly selective first-generation EGFR-TKI (3). Icotinib is indicated for the treatment of EGFR mutation-positive, advanced or metastatic NSCLC, or as a second- or third-line treatment (3). However, the majority of patients with NSCLC develop an acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs 8–10 months following the initiation of treatment (2,4). It has been previously demonstrated that a second point mutation on EGFR in exon 20 (T790 M) and a MET gene amplification underlie the development of an acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs in patients with NSCLC (5–8). However, the mechanisms underlying acquired resistance are not determined for ~30% of cases (5).

Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN; deleted on chromosome 10) is a tumor-suppressor gene that has dual-specificity phosphatase activity (9). PTEN is mutated in various types of human cancer and regulates cellular growth using hyperphosphorylation and dephosphorylation (10). PTEN may be involved in the infiltration and migration of tumor cells and may affect vessel formation (11). The tumorigenesis of lung cancer is a complex biological process; the present study identified that PTEN is inactivated and abnormally expressed in lung cancer (11). It was hypothesized that the loss of PTEN expression may contribute to the development of EGFR-TKI resistance in EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC. In the current study, the effect of icotinib on HCC827 cells and the association between PTEN expression levels and cell sensitivity to icotinib was evaluated; gene expression levels and the biological behavior of HCC827 cells was also investigated for each group. The aim of the present study was to elucidate the mechanisms underlying acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

The HCC827 NSCLC cell line was provided by Xi'an Jiaotong University (Xi'an, China); the HCC827 cells had an acquired E746-A750 deletion mutation in the EGFR tyrosine kinase domain. The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Hyclone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Icotinib was purchased from Zhejiang Beida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). MTT, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and propidium iodide (PI) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Anti-PTEN (#9552; dilution, 1:2,000) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (H+L; #AP60720; dilution, 1:2,000) was obtained from Abgent Biotech Co., Ltd. (Suzhou, China) and the anti-β-actin antibody (#sc-130300; dilution, 1:1,500) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA).

PTEN-small interfering (si)RNA design, synthesis and transfection

siRNAs corresponding to PTEN (upstream, 5′-GUAUGACAACAGCCUCAAGTT-3′; downstream, 5′-CUUGAGGCUGUUGUCAUACTT-3′) were purchased from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The cells were plated in culture plates in RPMI-1640 (HyClone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Following culturing to 70–80% confluency on 6-well plates, the cells were then transfected with siRNA or FAM-negative siRNA using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Following a 6-h incubation period at 37°C with the transfection reagents, the transfection medium was replaced with RPMI-1640 supplemented with 20% FBS. The cells were then incubated at 37°C for 24–48 h in 5% CO2. Two wells were left untransfected to serve as a negative control.

Drugs and growth-inhibition assay

Cells were seeded at a density of 2–4×103/100 µl in 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C overnight in 5% CO2. Subsequently, various concentrations (0.5 nmol/l, 1 nmol/l, 2 nmol/l, 4 nmol/l, 8 nmol/l) of icotinib were added; following incubation times of 24, 48 and 72 h at 37°C, 20 µl MTT (5 mg/l) was added to each well and the plates were incubated for 4 h at 37°C. Then, 150 µl DMSO was oscillated for 10 min and the absorbance was measured at 490 nm with a 96-well plate reader (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Each concentration was investigated in triplicate and was analyzed by SPSS version 17.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) was considered to be the concentration that resulted in 50% cell growth inhibition, as compared with the untreated control cells.

Cell apoptosis assay

Exponentially growing cell suspensions were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 2–4×103/100 µl. The following day, various concentrations (0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 nmol/l) of icotinib were added. Following incubation for 72 h at 37°C, the cells (0.5–1×106/ml) were collected, washed with cold PBS and 500 µl binding buffer was added; subsequently, 5 µl Annexin V/fluorescein isothiocyanate (Shaanxi Xianfeng Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Xi'an, China) and 10 µl PI was added to each well, in the absence of light, and mixed. The plates were incubated for 15 min at 37°C and evaluated using flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) within 1 h.

Cell cycle assay

Exponentially growing cell suspensions (0.5–1×106/ml) were seeded into 6-well plates. Following an overnight incubation at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2, various concentrations of icotinib (0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 nmol/l) were added. The cells were incubated for 72 h at 37°C then collected and washed with cold PBS. The samples were frozen in 70% ethanol at −20°C and kept overnight. The cells were subsequently washed with cold PBS, and 150 µl RNase (5 g/l; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck Millipore) and 150 µl PI (50 µg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck Millipore) were added. The cells were solubilized for 30 min without light and were evaluated using flow cytometry (FACSCalibur).

Western blot analysis

The cells were washed twice with PBS and solubilized in a protein lysis buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The supernatants, containing the whole-cell protein extracts, were obtained following centrifugation (18,894.2 × g) for 15 min at 4°C. The protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic protein assay (Shaanxi Xianfeng Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Heat-denatured protein samples (30 µg per lane) were resolved using 8% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membrane was incubated for 60 min in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (Ameresco, Inc., Framingham, MA, USA) and 5% skim milk to block non-specific binding; this was followed by incubation overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against PTEN and β-actisn. The membrane was washed four times for 8 min each in PBS with 0.1% Tween-20, then incubated for 2 h with a conjugated horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody. The membrane was washed thoroughly in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 and the bound antibody was detected using enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents (EMD Millipore), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The results of the western blotting were analyzed using ImageJ2x (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MA, USA).

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

The total RNA (1,248.52 ng/µl) from cells was extracted using RNA Fast200 (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck Millipore). The PCR amplification reaction mixture (10 µl) contained the following: 5*PrimeScript buffer (2 µl), PrimeScript RT enzyme mix (0.5 µl), oligo dT primer (0.5 µl), random hexanucleotide (0.5 µl), total RNA (4 µl) and RNase Free (Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu Japan). The thermal cycler conditions were as follows: 94°C for 2 min then 35 cycles alternating between 94°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 2 min. The target gene expression levels were normalized to GAPDH levels. The formula 2ss(−ΔCq)=2[Cq (GAPDH)-Cq(target)] was used to calculate the relative gene expression levels for each sample, reflecting the normalized target gene expression levels. The primer sequences were as follows: Upstream, 5′-CTATTCCCAGTCAGAGGCGCTAT-3′; downstream, 5′-TGAACTTGTCTTCCCGTCGTGT-3′.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 17.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical analysis was conducted using an independent t-test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Icotinib inhibited the growth of HCC827 cells

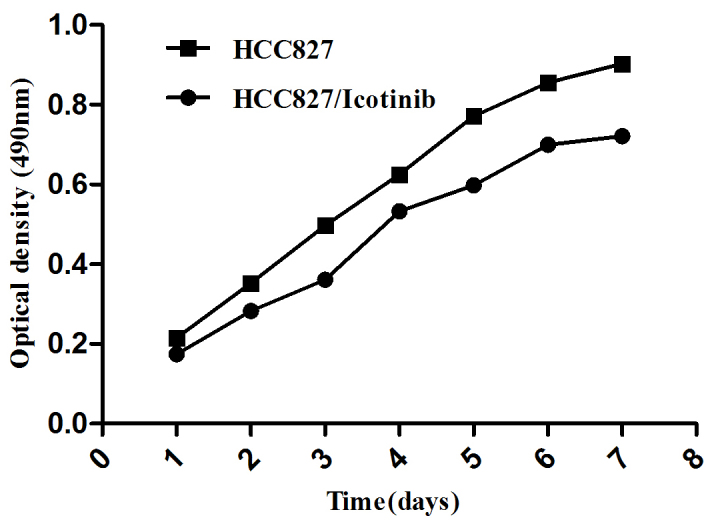

To study the effects of icotinib on HCC827 lung cancer cells, an MTT assay was used to test cell growth and survival (Fig. 1). The present study identified that icotinib induces damage to HCC827 cells, which was enhanced with increasing time and concentration (P=0.001).

Figure 1.

The effect of icotinib treatment on the growth of HCC827 cells. A cell growth curve presents the ordinate with optical density and time as abscissas. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation for three independent experiments. *P<0.05, vs. the control.

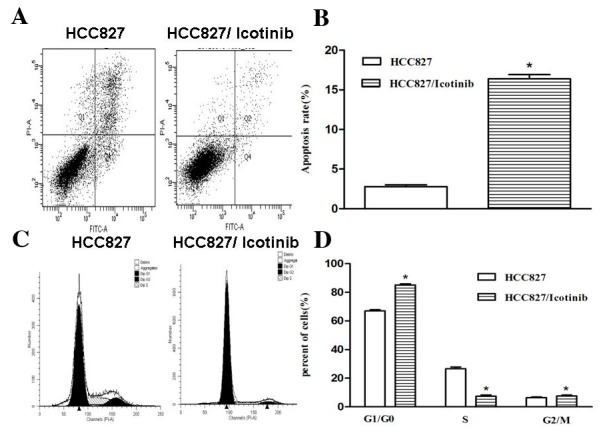

Icotinib inhibits cell apoptosis and the cell cycle of HCC827 cells

As indicated in Fig. 2, treatment with icotinib significantly inhibited the proliferation and increased the rate of apoptosis of HCC827 cells (P<0.001; Fig. 2A and B). The number of cells in the G0/G1 cell cycle phase was increased following treatment with icotinib, compared with the control group, suggesting that icotinib significantly attenuated the cell cycle in the G0/G1 phase (P<0.001; Fig. 2C and D).

Figure 2.

The impact of icotinib on the apoptosis and cell cycle of HCC827 cells. (A) An FCM analysis of apoptotic cells using Annexin V/PI. Q1 depicts the cells that were damaged during the experiment (Annexin V-/PI+); Q2 indicates late-stage apoptotic cells and necrotic cells (Annexin V+/PI+); Q3 depicts normal cells (Annexin V-/PI-); Q4 indicates early apoptotic cells (Annexin V+/PI-). (B) The rate of apoptosis of HCC837 cells in the control group was 2.7±0.46%; following treatment with icotinib the apoptosis rate increased to 16.4±0.91%. (C) An FCM analysis of the cell cycle. (D) In the control group, 66.96±1.42% of the cells were in the G0/G1 phase, 26.58±2.12% of the cells were in the S phase and 6.46±2.59% of the cells were in the G2/M phase. With icotinib, 85.11±1.31% of the cells were in G0/G1 phase, while 7.37±1.53% of the cells were in S phase and 7.52±1.15% of the cells were in G2/M phase. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments. *P<0.05, vs. the control. FCM, flow cytometry; PI, propidium iodide; Q, quadrant.

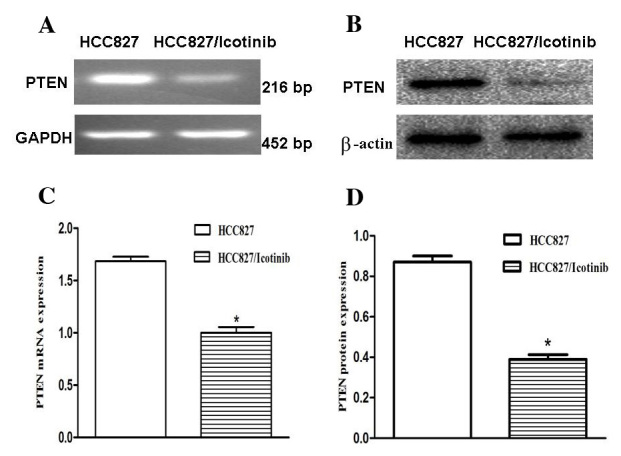

Icotinib downregulates PTEN expression

To investigate the association between icotinib and its relevant effects, the expression levels of PTEN were examined using RT-qPCR and western blotting (Fig. 3A and B). The RT-qPCR results revealed that PTEN mRNA expression levels were decreased by ~34% following treatment with icotinib (P<0.001; Fig. 3C). The results of the western blotting demonstrated that the protein expression levels of PTEN in the HCC827 cells were significantly downregulated (P<0.001; Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

The impact of icotinib on PTEN expression levels in HCC827 cells. (A and B) The PTEN mRNA and protein expression levels in the HCC827 and icotinib-treated HCC827 cells were detected using RT-qPCR and western blotting, respectively. (C) RT-qPCR demonstrated that PTEN expression levels were decreased by ~34% following treatment with icotinib (*P<0.05). (D) Western blot demonstrating that PTEN protein expression was also significantly downregulated (*P<0.05). GAPDH or β-actin was used as a control for sample loading. *P<0.05 vs. the control. PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

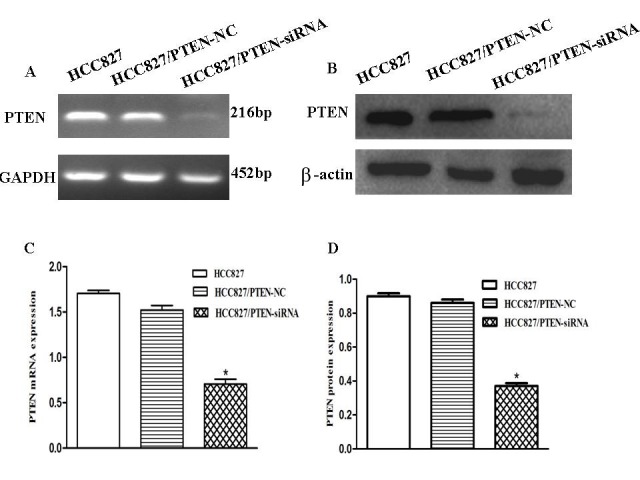

PTEN in HCC827 cells is downregulated by transient transfection

To evaluate the effects of the downregulation of PTEN expression in HCC827 lung cancer cells, the cells were transfected with an siRNA corresponding to PTEN. To determine whether PTEN expression in HCC827 cells was downregulated, RT-qPCR and western blotting were used to analyze the PTEN expression levels in each group (Fig. 4A and B). RT-qPCR demonstrated that PTEN expression levels decreased by ~52% following transfection, suggesting that PTEN was significantly downregulated by PTEN-siRNA (P<0.001; Fig. 4C). The protein expression levels of PTEN in the HCC827 cells were significantly decreased following transfection with the PTEN siRNA, as compared with the control (P<0.001; Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

PTEN expression in HCC827 cells was successfully downregulated by PTEN-siRNA. (A and B) The PTEN mRNA and protein expression levels in the HCC82, HCC827/PTEN-NC and HCC827/PTEN-siRNA cells were detected using RT-qPCR and western blotting, respectively. (C) RT-qPCR revealed that PTEN expression levels were decreased by ~52% following transfection, suggesting that PTEN was successfully downregulated by PTEN-siRNA. (D) Western blotting demonstrating that PTEN protein expression was also significantly downregulated (*P<0.05). GAPDH or β-actin was used as a control for sample loading. *P<0.05, vs. the control. PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; NC, negative control; siRNA, small-interfering RNA.

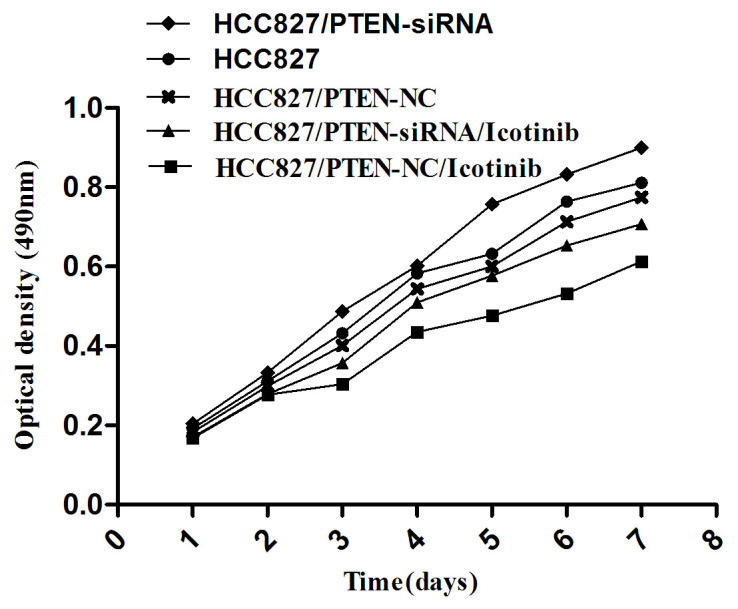

Silencing PTEN expression promotes the growth of HCC827 cells

An MTT assay was used to examine cell growth in each group, as indicated in Fig. 5; the growth of HCC827 cells was observed to be inhibited by icotinib treatment (P=0.0042). However, the growth of HCC827 cells was promoted if the PTEN gene was silenced (P=0.0117).

Figure 5.

The cell growth curve for each group. A cell growth curve presents the absorbance values with the ordinate and time as abscissas. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments. PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; NC, negative control; siRNA, small-interfering RNA.

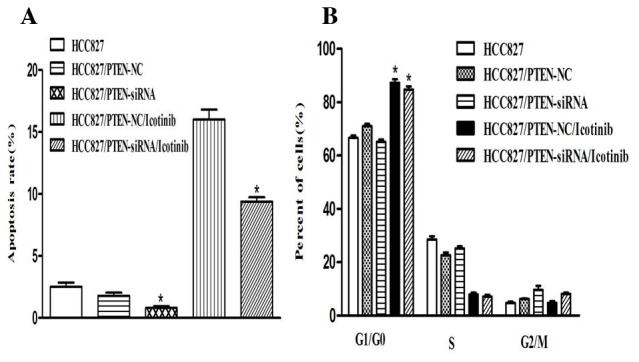

Silencing PTEN expression decreases the apoptosis of HCC827 cells

Transfection with PTEN siRNA decreased the rate of apoptosis of HCC827 cells, compared with the control group (P<0.001). Concordant with the previous results, the number of cells in the G0/G1 phase was increased following icotinib treatment (P<0.001) and no significant difference was observed between the control and PTEN-siRNA groups (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

The impact of silencing PTEN expression on the apoptosis and cell cycle of HCC827 cells, following treatment with icotinib. (A) Transfection of PTEN siRNA decreased the rate of apoptosis of HCC827 cells, compared with the control group (0.80±0.24% and 2.53±0.54%). (B) A flow cytometry analysis of the cell cycle. The cell fractions in the G0/G1 phase were increased following icotinib treatment (71.08±1.35% and 87.31±2.26%) and no significant difference was observed between the control and PTEN-siRNA groups (66.62±1.42% and 61.14±1.53%). The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments. *P<0.05, vs. the control. PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; siRNA, small interfering RNA; NC, negative control.

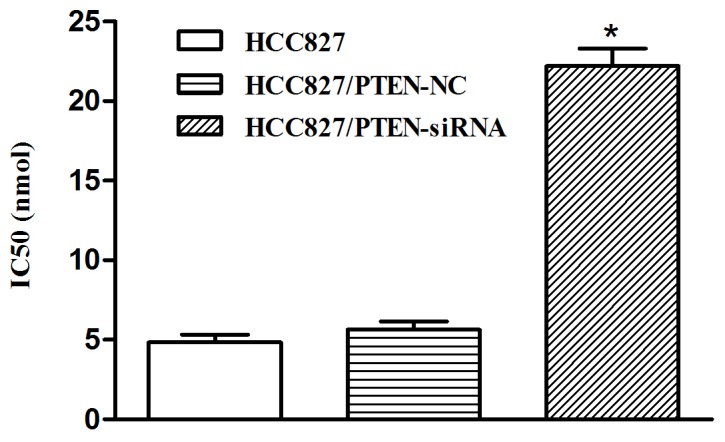

Silencing PTEN expression decreases the sensitivity of HCC827 cells to icotinib

In the HCC827 cells transfected with PTEN siRNA, the inhibition rate of icotinib was significantly decreased, compared with the control group, and the IC50 was significantly increased (22.52 nmol) following transfection (P<0.001; Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

The altered sensitivity of HCC827 cells to icotinib, following transfection. The concentration of icotinib required to inhibit 50% of the HCC827 cells was defined as the IC50 value. The IC50 for the HCC827 cells in the control group was determined to be 4.99 nmol, 5.63 nmol for the group transfected with PTEN-NC and 22.52 nmol following transfection with PTEN-siRNA. *P<0.05, vs. control. NC, negative control; siRNA, small-interfering RNA; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog.

Discussion

Icotinib hydrochloride is an EGFR-TKI that targets the mutated EGFR gene (3). If ligands including epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor or amphiregulin are combined with the extracellular domain of EGFR, the intracellular tyrosine kinase may be activated and combine with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (12). The phosphorylation of ATP activates downstream signal transduction pathways, including the rat sarcoma (RAS)/mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) and proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src signaling pathway, which may induce tumor cell proliferation, anti-apoptosis, invasion and metastasis (5).

It has previously been reported that EGFR-TKIs may suppress tumor growth by binding to the intracellular domain (magnesium-ATP) of EGFR, which may inhibit the activity and phosphorylation of the tyrosine kinase and block downstream signal transduction pathways (12). However, the majority of patients with NSCLC develop an acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs within 8–10 months (13). A previous study on TKI-sensitive NSCLC indicated that a mutation in the EGFR tyrosine kinase domain is responsible for activating various anti-apoptotic signaling pathways (14). An EGFR mutation may be detected in 43–89% of patients with lung cancer; mutations on exons 19 and 21 are the most common (15). These mutations have been observed to confer increased cell sensitivity to TKIs, including to icotinib (3). In addition to a second point mutation in EGFR on exon 20 (T790 M) and a MET gene amplification, Kirsten-RAS, PIK3, insulin-like growth factor-1 and epithelial-mesenchymal transition target gene amplification mutations are also associated with acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs (13,14,16).

Similar to other EGFR-TKIs, icotinib may induce cell proliferation inhibition, cell apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by inhibiting the activity and phosphorylation of the tyrosine kinase domain (3). The current study identified that icotinib may damage HCC827 cells in a time- and concentration-dependent manner. Treatment with icotinib significantly inhibited the proliferation and increased the rate of apoptosis of HCC827 cells, in which the mRNA and protein expression levels of PTEN were significantly downregulated. The PTEN gene is a tumor suppressor gene located on chromosome 10q23.3 (10). PTEN is frequently mutated in a variety of types of human cancer, including glioblastoma, melanoma, breast, prostate, renal and endometrial carcinoma (11). PTEN exerts its tumor-suppressor effects through its phosphatase domain and C2 domain (17). It may inhibit phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate phosphorylation by specifically antagonizing the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and suppressing Akt expression, which may induce the apoptosis of Akt-dependent cells (17–21).

A previous study has reported that alterations in PTEN in NSCLC cell lines are associated with a loss of heterozygosity, or with gene deletion (22). Loss of PTEN is involved in the development of EGFR inhibitor resistance in certain tumor cell lines (23,24) and in patients with glioblastoma (25). The underlying mechanisms may include promoter hypermethylation, post-translational modifications or the alternative splicing of the pre-mRNA (26).

PTEN expression patterns in NSCLC require further study, and the role of PTEN in icotinib treatment in NSCLC has yet to be fully elucidated. Yamamoto et al (22) constructed a PC-9/GR EGFR-TKI resistant cell line, and identified that its PTEN expression levels were significantly decreased, and phosphorylated Akt levels were significantly increased. In the present study, it was identified that PTEN mRNA and protein expression levels were significantly downregulated following icotinib treatment. Silencing PTEN expression may promote cell proliferation, decrease the rate of apoptosis of HCC827 cells and reduce the sensitivity of HCC827 cells to icotinib. The current study hypothesized that the underlying mechanisms may involve the loss of PTEN with an increasing PIP-3 concentration, the hyperactivation of Akt and the subsequent release of cytochrome c and the inactivation of forkhead, caspase-9 and B-cell-lymphoma-2 associated agonist of cell death (26). PTEN may influence cell proliferation and apoptosis by regulating the MAPK signaling pathway and the extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase cell survival pathway (22,27,28).

In conclusion, the present study identified that PTEN expression levels affected the sensitivity of HCC827 cells to icotinib treatment, indicating that PTEN may be involved in regulating the icotinib-induced cytotoxicity of HCC827 cells. These results suggest that PTEN may serve as a novel target for monitoring the sensitivity of NSCLC cells to EGFR-TKIs, including icotinib in patients with lung cancer.

References

- 1.Walker S. Updates in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12:587–596. doi: 10.1188/08.CJON.587-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu Q, Wang Y, Liu H, Meng S, Zhou S, Xu J, Schmid-Bindert G, Zhou C. Treatment outcome for patients with primary NSCLC and synchronous solitary metastasis. Clin Transl Oncol. 2013;15:802–809. doi: 10.1007/s12094-013-1008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan F, Shi Y, Wang Y, Ding L, Yuan X, Sun Y. Icotinib, a selective EGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Future Oncol. 2015;11:385–397. doi: 10.2217/fon.14.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Endoh H, Yoshida K, Hida T, Tsuboi M, Tada H, Kuwano H, Mitsudomi T. Analysis of epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and acquired resistance to gefitinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5764–5769. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onitsuka T, Uramoto H, Nose N, Takenoyama M, Hanagiri T, Sugio K, Yasumoto K. Acquired resistance to gefitinib: The contribution of mechanisms other than the T790M, MET and HGF status. Lung Cancer. 2010;68:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sos ML, Rode HB, Heynck S, Peifer M, Fischer F, Klüter S, Pawar VG, Reuter C, Heuckmann JM, Weiss J, et al. Chemogenomic profiling provides insights into the limited activity of irreversible EGFR Inhibitors in tumor cells expressing the T790M EGFR resistance mutation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:868–874. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ju L, Zhou C. Association of integrin beta1 and c-MET in mediating EGFR TKI gefitinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2013;13:15. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-13-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bean J, Brennan C, Shih JY, Riely G, Viale A, Wang L, Chitale D, Motoi N, Szoke J, Broderick S, et al. MET amplification occurs with or without T790M mutations in EGFR mutant lung tumors with acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20932–20937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710370104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eng C. PTEN: One gene, many syndromes. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:183–198. doi: 10.1002/humu.10257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ortega-Molina A, Serrano M. PTEN in cancer, metabolism, and aging. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2013;24:184–189. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soria JC, Lee HY, Lee JI, Wang L, Issa JP, Kemp BL, Liu DD, Kurie JM, Mao L, Khuri FR. Lack of PTEN expression in non-small cell lung cancer could be related to promoter methylationc. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1178–1184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mezzapelle R, Miglio U, Rena O, Paganotti A, Allegrini S, Antona J, Molinari F, Frattini M, Monga G, Alabiso O, Boldorini R. Mutation analysis of the EGFR gene and downstream signalling pathway in histologic samples of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1743–1749. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu H, Arcila ME, Rekhtman N, Sima CS, Zakowski MF, Pao W, Kris MG, Miller VA, Ladanyi M, Riely GJ. Analysis of tumor specimens at the time of acquired resistance to EGFR-TKI therapy in 155 patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2240–2247. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones HE, Goddard L, Gee JM, Hiscox S, Rubini M, Barrow D, Knowlden JM, Williams S, Wakeling AE, Nicholson RI. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signalling and acquired resistance to gefitinib (ZD1839; Iressa) in human breast and prostate cancer cells. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;11:793–814. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boch C, Kollmeier J, Roth A, Stephan-Falkenau S, Misch D, Grüning W, Bauer TT, Mairinger T. The frequency of EGFR and KRAS mutations in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Routine screening data for central Europe from a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002560. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002560. pii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma C, Wei S, Song Y. T790M and acquired resistance of EGFR TKI: A literature review of clinical reports. J Thorac Dis. 2011;3:10–18. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2010.12.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tian T, Nan KJ, Guo H, Wang WJ, Ruan ZP, Wang SH, Liang X, Lu CX. PTEN inhibits the migration and invasion of HepG2 cells by coordinately decreasing MMP expression via the PI3K/Akt pathway. Oncol Rep. 2010;23:1593–1600. doi: 10.3892/or_00000800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chalhoub N, Baker SJ. PTEN and the PI3-kinase pathway in cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:127–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leslie NR, Downes CP. PTEN function: How normal cells control it and tumour cells lose it. Biochem J. 2004;382:1–11. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moon SH, Kim DK, Cha Y, Jeon I, Song J, Park KS. PI3K/Akt and Stat3 signaling regulated by PTEN control of the cancer stem cell population, proliferation and senescence in a glioblastoma cell line. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:921–928. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fidler MJ, Morrison LE, Basu S, Buckingham L, Walters K, Batus M, Jacobson KK, Jewell SS, Coon J, IV, Bonomi PD. PTEN and PIK3CA gene copy numbers and poor outcomes in non-small cell lung cancer patients with gefitinib therapy. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1920–1926. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamamoto C, Basaki Y, Kawahara A, Nakashima K, Kage M, Izumi H, Kohno K, Uramoto H, Yasumoto K, Kuwano M, Ono M. Loss of PTEN expression by blocking nuclear translocation of EGR1 in gefitinib-resistant lung cancer cells harboring epidermal growth factor receptor-activating mutations. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8715–8725. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamasaki F, Johansen MJ, Zhang D, Krishnamurthy S, Felix E, Bartholomeusz C, Aguilar RJ, Kurisu K, Mills GB, Hortobagyi GN, Ueno NT. Acquired resistance to erlotinib in A-431 epidermoid cancer cells requires down-regulation of MMAC1/PTEN and up-regulation of phosphorylated Akt. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5779–5788. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.She QB, Solit DB, Ye Q, O'Reilly KE, Lobo J, Rosen N. The BAD protein integrates survival signaling by EGFR/MAPK and PI3K/Akt kinase pathways in PTEN-deficient tumor cells. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mellinghoff IK, Wang MY, Vivanco I, Haas-Kogan DA, Zhu S, Dia EQ, Lu KV, Yoshimoto K, Huang JH, Chute DJ. Molecular determinants of the response of glioblastomas to EGFR kinase inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2012–2024. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang YS, Wang YH, Xia HP, Zhou SW, Schmid-Bindert G, Zhou CC. MicroRNA-214 Regulates the Acquired Resistance to Gefitinib via the PTEN/AKT pathway in EGFR-mutant cell lines. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:255–260. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sos ML, Koker M, Weir BA, Heynck S, Rabinovsky R, Zander T, Seeger JM, Weiss J, Fischer F, Frommolt P, et al. PTEN loss contributes to erlotinib resistance in EGFR-mutant lung cancer by activation of Akt and EGFR. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3256–3261. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ludovini V, Bianconi F, Pistola L, Chiari R, Minotti V, Colella R, Giuffrida D, Tofanetti FR, Siggillino A, Flacco A, et al. Phosphoinositide-3-kinase catalytic alpha and KRAS mutations are important predictors of resistance to therapy with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:707–715. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31820a3a6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]