Abstract

The aim of the present study was to determine whether age, gender, functional status, histology, tumor location, number of metastases, and levels of the tumor markers, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and albumin, are poor prognostic factors for the response to chemotherapy in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary site. A total of 149 patients diagnosed with carcinoma of unknown primary site that was histologically confirmed, and treated with chemotherapy in the Oncology Hospital, National Medical Center, ‘Century XXI’ IMSS, Mexico City, Mexico during the period between January 2002 to December 2009, were carefully selected for the present study. The analysis of 149 patients diagnosed with carcinoma of unknown primary site revealed that the liver was the organ with the highest frequency of metastases (33.5%). The objective response rates to chemotherapy were ~30.2%. Notably, ECOG was an important predictor of response to chemotherapy (P=0.008). The median progression-free survival was 7.1 months. Upon multivariate analysis, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Scale of Performance Status was observed as an independent predictor of progression (P<0.0001). The median overall survival was 14.2 months. The ECOG was also an independent predictor of mortality (P<0.0001). In conclusion, the data from the present study have demonstrated that ECOG is an independent predictor of a poor response to chemotherapy, lower overall survival and progression-free survival in carcinoma of unknown primary site.

Keywords: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, chemotherapy, overall survival, progression-free survival, carcinoma of unknown primary site

Introduction

Cancer of unknown primary (CUP) is a heterogeneous group of malignancies that are defined as the presence of metastases, without identifying a primary tumor following an extensive evaluation of the patient (1). The identification of the primary tumor represents a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge: the antemortem frequency of detection of the primary site is <20–30% (2), meanwhile CUP represents between 2.3 and 4.2% of adult cancers (3). In Mexico, 4,223 new cases of CUP were diagnosed in 2001, representing ~4% of cancer cases during that year (4). Unfortunately, the median survival rate, even in patients treated with cytotoxic agents, was <1 year (5). Chemotherapy has been the cornerstone in the treatment of CUP; however, establishment of the results has been difficult due to the heterogeneity of patients in the series. CUP treatment must be individualized according to the clinical setting, considering the favorable or unfavorable group that the patient belonged to prior to the therapeutic decision. However, the benefits of chemotherapy compared with best supportive care in the subgroups of poor prognosis have yet to be fully elucidated, and the optimal treatment regimen has not been determined (6). Several chemotherapy schemes have been successful in groups of patients with favorable clinical characteristics. However, most patients with CUP are in the unfavorable group, and this exhibits low rates of response to systemic treatment, which is decided empirically according to clinical and functional status. On the other hand, it has been proposed that clinicopathological features, including age, gender, functional status, weight loss, histology, tumor location, number of metastases and the levels of tumor markers, may represent relevant prognostic variables (7–14). These variables have not been obtained consistently, and so larger studies are required to validate specific clinical, pathological and molecular profiles in order to differentiate patients that are likely to benefit from treatment from those who would be likely to experience only deterioration in their quality of life. There are no well-established clinical and molecular markers for CUP, and therefore recognition of such markers is of vital importance in determining the best treatment option. The aim of the present study was to determine whether clinicopathological parameters were prognostic factors for the response to chemotherapy in patients with CUP. Overall survival, progression-free survival and response rates to chemotherapy were investigated in the present study.

Patients and methods

Patients

A total of 149 patients with CUP treated at the Oncology Hospital, National Medical Center ‘Century XXI’, IMSS, Mexico City, Mexico between January 2002 and December 2009 were retrospectively analyzed. Patients >18 years of age diagnosed with CUP, who were histologically confirmed and with any histological subtype, were carefully selected. Patients previously treated in other units, those with hematological, renal or liver failure at the time of inclusion, or those with the presence of a second neoplasm were excluded. The clinicopathological factors analyzed were: Age, gender, functional status, histology, tumor location, number of metastases, and the levels of the tumor markers, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and albumin.

Statistical analysis

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the lifetime in months from the start of treatment until the patient succumbed to mortality. Progression-free survival (PFS) was determined from the start of the treatment to the date on which the disease progressed, determined clinically or by imaging, either by increasing tumor volume or development of new lesions. Response criteria were as follows: Complete response (CR) indicated no measurable tumor by clinical analysis and/or by imaging; partial response (PR) referred to a reduction of ≥30% in the largest diameter of one of the target lesions compared with the baseline study; and stable disease (SD) referred to a measurable reduction in tumor volume of <30% in maximum diameter, with no appearance of new lesions. Toxicity to treatment was determined according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE, https://ctep.cancer.gov). For the statistical analysis, comparison between subgroups was performed using the Chi-square test for quantitative variables, and Fisher's exact test for qualitative variables. The analysis of OS and PFS was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method with confidence intervals (CIs) of 95%. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 17 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For univariate analysis, a statistical comparison of median survival with the t-test was used, and multivariate analysis was performed using the Cox model. Only the variables with P<0.05, on performing a univariate analysis, were included in the present study. Proportional hazards were analyzed using graphical and statistical methods. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant value.

Results

Patient characteristics

A cohort of 149 patients diagnosed with CUP treated between January 2002 and December 2009 were carefully selected for the present study. Table I shows the clinicopathological characteristics of the patients involved in this study. Of the patients, 60% received only one line of chemotherapy. The mean age was 56.9 years (range, 25–90) and the numbers of patients according to gender (51.67% male, 48.32% female) were similar. A total of 65.7% of subjects had ECOG-1, whereas adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma accounted for 85.57% of the histologies. A total of 75% of the tumors had a poor degree of differentiation tumor activity, which was confirmed in 2–3 sites in 53.69% of the cases. Molecular analysis revealed that there was an elevation in the levels of the tumor marker, cancer antigen 125 (CA125), in 34.22% of cases, being the most frequent biomarker (16.77%). A significant increase in the expression of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was identified in 41.6% of the patients, and the level of albumin decreased in 12.1% of the individuals.

Table I.

Characteristics of patients with CUP from January 2002 to December 2009.

| Characteristic | Number of patients | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 77 | 51.67 |

| Female | 72 | 48.32 |

| Age (years) | ||

| Median ± SD | 56.94±12.69 | – |

| Range | (25–90) | |

| ECOG performance status | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 98 | 65.77 |

| 2 | 49 | 32.88 |

| 3 | 2 | 1.34 |

| Histology | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 18 | 12.08 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 72 | 48.32 |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 2 | 1.34 |

| Carcinoma | 57 | 38.25 |

| Differentiation grade | ||

| Well differentiated | 4 | 2.68 |

| Moderately differentiated | 34 | 22.81 |

| Poorly differentiated | 111 | 74.49 |

| Number sites of disease | ||

| 1 | 49 | 0.67 |

| 2–3 | 80 | 53.69 |

| >3 | 20 | 13.42 |

| Elevated tumor marker | 51 | 34.22 |

| CEA | 23 | 15.43 |

| AFP | 4 | 2.68 |

| bHGC | 0 | 0 |

| PSA | 2 | 1.34 |

| CA125 | 25 | 16.77 |

| CA19–9 | 6 | 4.02 |

| LDH (>340 IU/l) | 62 | 41.60 |

| Albumin <3.4 g/dl | 18 | 12.10 |

| Number of chemotherapy | ||

| schemes | ||

| 1 | 90 | 60.40 |

| 2 | 42 | 28.18 |

| 3 | 13 | 8.72 |

| >3 | 4 | 2.68 |

CUP, cancer of unknown primary; SD, standard deviation; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; AFP, α-fetoprotein; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; BHGC, β-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin; SA, prostate-specific antigen; CA125, cancer antigen 125; CA19-9, cancer antigen 19-9.

Location of metastases

Table II describes the location of the various sites of metastases in patients. The most frequently observed locations were the liver (33.5% of patients), neck (30.2%), lung (24.8%), supraclavicular (18.1%), bone (16.7%), axillar (15.4%), peritoneum (14.0%), mediastinum and retroperitoneum (13.4%). Other less frequent locations (<10%) were localized in the pleura, skin, groin, pelvis, central nervous system, small intestine, colon, pancreas, parotid, pericardium and adrenal. Tumor activity was reported in the spleen, stomach, breast and bone marrow in 1% of the patients.

Table II.

Location of tumor activity in patients with CUP (n=149).

| Site of location | Number of cases | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Liver | 50 | 33.5 |

| Cervical | 45 | 30.2 |

| Lung | 37 | 24.8 |

| Supraclavicular | 27 | 18.1 |

| Bone | 25 | 16.7 |

| Axilla | 23 | 15.4 |

| Peritoneum | 21 | 14.0 |

| Mediastinum | 20 | 13.4 |

| Retroperitoneum | 20 | 13.4 |

| Pleura | 11 | 7.3 |

| Skin | 9 | 6.0 |

| Groin | 8 | 5.3 |

| Pelvis | 6 | 4.0 |

| Central nervous system | 5 | 3.3 |

| Small intestine | 3 | 2.0 |

| Colon | 2 | 1.3 |

| Pancreas | 2 | 1.3 |

| Parotid | 2 | 1.3 |

| Pericardium | 2 | 1.3 |

| Adrenal | 2 | 1.3 |

| Spleen | 1 | 0.67 |

| Gastric | 1 | 0.67 |

| Breast | 1 | 0.67 |

| Bone marrow | 1 | 0.67 |

CUP, cancer of unknown primary.

Response rates

A total of 45 patients (30.2%) demonstrated a response to chemotherapy, of whom 12 patients (8.1%) presented with CR, and 33 patients (22.1%) exhibited PR. SD was observed in 17 patients (11.4%). Eighty-three patients (55.7%) progressed during treatment, and 4 patients (2.7%) did not exhibit any response. A total of 21 cases of mortality (14.1%) were associated with a diagnostic confirmatory note in the record (Table III). Notably, univariate analysis showed that ECOG (P=0.004), elevated levels of LDH (P=0.03) and histology (P=0.031) were prognostic factors for the response to chemotherapy (Table IV). Subsequently, a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors of the response to chemotherapy was performed using a logistic regression model. Notably, the results demonstrated that the ECOG was significantly associated (P=0.008) with the chemotherapy response (Table V).

Table III.

Response rates to chemotherapy of patients with CUP (n=149).

| Type of response | Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Response | ||

| Complete | 12 | 8.1 |

| Parcial | 33 | 22.1 |

| Global | 45 | 30.2 |

| Progression | 83 | 55.7 |

| No response | 4 | 2.7 |

| Stable disease | 17 | 11.4 |

| Mortalities | 21 | 14.1 |

CUP, cancer of unknown primary.

Table IV.

Univariate analysis of prognostic factors of response to chemotherapy.

| Variable | CR (%) n=12 | PR (%) n=33 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.75 | ||

| Male | 5 (41.7) | 18 (54.5) | |

| Female | 7 (58.3) | 15 (45.5) | |

| ECOG | 0.004 | ||

| 1 | 11 (91.7) | 26 (78.8) | |

| 2 | 1 (8.3) | 7 (21.2) | |

| 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Histology | 0.031 | ||

| NET | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 3 (25.0) | 7 (21.2) | |

| Carcinoma | 4 (33.3) | 10 (30.3) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 5 (41.7) | 16 (48.5) | |

| Differentiation grade | 0.46 | ||

| Well differentiated | 0 (0) | 1 (3.0) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 4 (33.3) | 11 (33.3) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 8 (66.7) | 21 (63.7) | |

| Tumor marker | 0.33 | ||

| Normal | 10 (83.3) | 23 (69.7) | |

| Elevated | 2 (16.7) | 10 (30.3) | |

| LDH | 0.03 | ||

| Normal | 11 (91.7) | 18 (54.5) | |

| Elevated >340 IU/l | 1 (8.3) | 15 (45.5) | |

| Albumin | 0.43 | ||

| Normal | 12 (100) | 29 (87.8) | |

| Decreased (<3.4 g/dl) | 0 (0) | 4 (12.2) |

CR, complete response; PR, partial response; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NET, neuroendocrine tumor; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Table V.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of prognostic factors of response to chemotherapy.

| Variable | β-value | OR | CI (95%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECOG | −1.13 | 0.42 | 0.13- 0.74 | 0.008 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Survival analysis

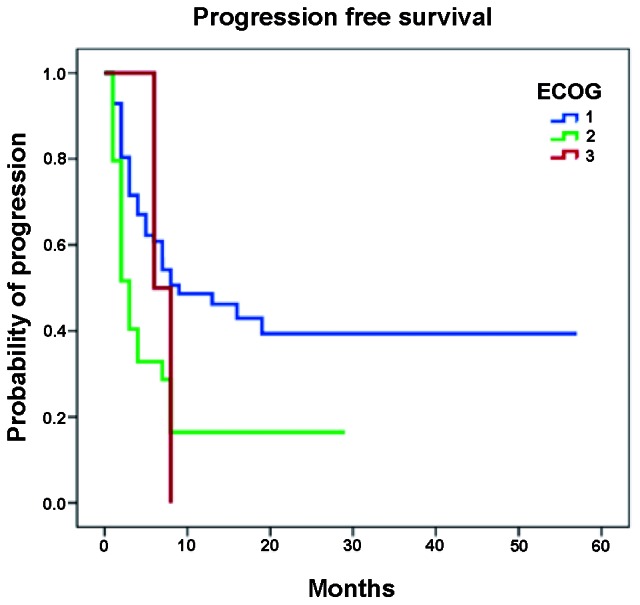

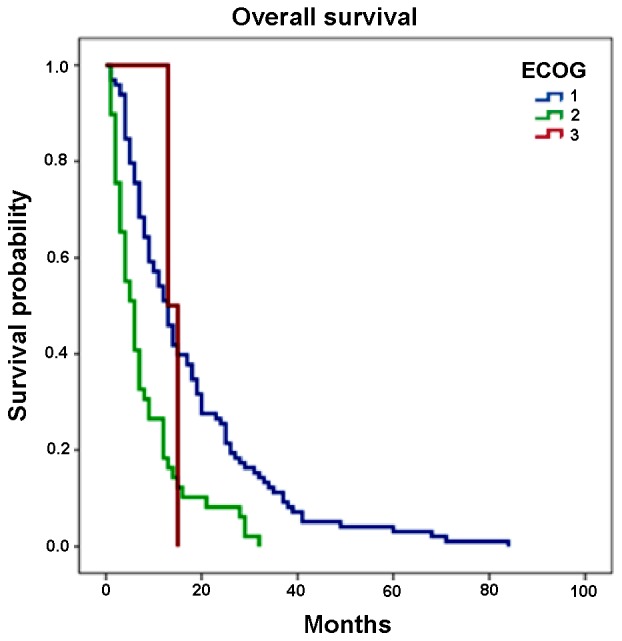

The PFS was 7.1±9.9 months (range, 1–57 months) (Table VI). Survival curves for PFS derived using the Kaplan-Meier method are shown in Fig. 1. Notably, in the univariate analysis, the ECOG and LDH had high statistical significance, as predictive of PFS (Table VII). On performing a multivariate logistic regression, only ECOG was observed as an independent factor of progression (P<0.0001; Table VIII). In addition, OS was 14.2±14.1 months (range, 1–84 months) as shown in Table IV. Survival curves derived using the Kaplan-Meier method for OS are shown in Fig. 2. The only independent predictor of mortality was the ECOG (P<0.0001); additional analysis revealed that there were no other clinical and pathological factors predictive of mortality.

Table VI.

Global survival and progression-free survival in patients with no known primary tumor (n=149).

| Survival | Months | ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | ||

| Median | 14.2 | 14.1 |

| Range | 1–84 | |

| Progression free survival | 9.09 | |

| Median | 7.1 | |

| Range | 1–57 | |

| ECOG | ||

| 1 | 25.9 (CI 95%, 19.5–32.4) | |

| 2 | 7.4 (CI 95%, 4.1–10.7) | |

| 3 | 7.0 (CI 95%, 5.0–8.9) |

SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence Interval; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for progression free survival in 149 patients with CUP, according to ECOG. CUP, cancer of unknown primary; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Table VII.

Univariate analysis of prognostic factors of progression to chemotherapy.

| Variable | Progression (%) n=83 | RR | CI, 95% | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.44 | |||

| Male | 41 (49.4) | |||

| Female | 42 (50.6) | 0.95 | 0.71–1.27 | |

| ECOG | ||||

| 1 | 46 (55.4) | |||

| 2 | 35 (42.2) | 0.65 | 0.49–0.86 | 0.004 |

| 3 | 2 (2.4) | 0.71 | 0.59–0.85 | 0.002 |

| Histology | 0.61 | |||

| NET | 0 (0) | |||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 8 (9.7) | |||

| Carcinoma | 33 (39.7) | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 42 (50.6) | |||

| Differentiation grade | 0.15 | |||

| Well differentiated | 2 (2.5) | |||

| Moderately differentiated | 15 (18.0) | |||

| Poorly differentiated | 66 (79.5) | |||

| Number of sites of disease | 0.29 | |||

| 1 | 24 (28.9) | |||

| 2–3 | 47 (56.7) | |||

| >3 | 12 (14.4) | |||

| Location of disease | 0.122 | |||

| Peritoneum | 8 (9.6) | 0.67 | 0.47- 0.95 | 0.1 |

| Lung, pleura | 14 (16.9) | 0.80 | 0.57–1.13 | 0.27 |

| Cervical | 19 (22.9) | 0.88 | 0.63–1.22 | 0.48 |

| Axilla, SCV | 8 (9.6) | 0.97 | 0.60–1.56 | 0.90 |

| Liver | 21 (25.3) | 1.13 | 0.81–1.56 | 0.43 |

| Bone | 5 (5.8) | 1.42 | 0.84–2.40 | 0.13 |

| Mediastinum | 4 (4.8) | 2.26 | 0.41–12.4 | 0.21 |

| Retroperitoneum | 4 (5.1) | 2.31 | 0.52–12.7 | 0.23 |

| Tumor marker | 0.52 | |||

| Normal | 49 (59.0) | |||

| Elevated | 34 (41.0) | 0.75 | 0.56–0.99 | |

| LDH | 0.031 | |||

| Normal | 42 (50.6) | |||

| Elevated (>340 IU/l) | 41 (49.4) | 0.73 | 0.55–0.96 | |

| Albumin | 0.13 | |||

| Normal | 70 (84.3) | |||

| Decreased (<3.4 g/dl) | 13 (15.7) | 0.74 | 0.53–1.02 |

RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NET, neuroendocrine tumor; SCV, supraclavicular; CNS, central nervous system; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Table VIII.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of prognostic factors of progression.

| Variable | β-value | OR | CI, 95% | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECOG | −1.226 | 0.37 | 1.4–6.08 | <0.0001 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival in 149 patients with CUP, according to ECOG. CUP, cancer of unknown primary; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Toxicity evaluation

Hematological toxicity, including anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia and neutropenia of any grade, occurred in 43.6% of patients; grade 3 to 4 was observed in 21.5% of the patients. Gastrointestinal toxicity (nausea, vomiting, mucositis, diarrhea, constipation, anorexia) in any degree was observed in 67.8% of the patients, documented at grades 3 to 4 in 20.2% of cases. Dermatological toxicity was reported in 53.02% of the patients, with alopecia being the most common cause (48.32%), and one case (0.7%) documented severe dermatological toxicity secondary to hand-foot syndrome. In addition, 16.8% of the patients reported neurological toxicity (sensory neuropathy and/or motor), and 5 cases (3.4%) reached grade 3 to 4. Almost two-thirds of the patients (64.4%) expressed a specific degree of constitutional symptoms, and 12.7% of the cases exhibited severely limiting or incapacitating conditions.

Discussion

The present study is a retrospective analysis of 7 years' experience in the treatment of patients with CUP in our institution. The primary endpoint was to determine clinicopathological factors that may confer lower response rates and decreased survival rates in patients with CUP, in order to establish subgroups of high and low risk, and identify those in whom chemotherapy did not yield any clinical benefits, but only toxic effects. In the present analysis, objective response rates to treatment were 30.2%, which was similar to those observed in the literature with platinum schemes (15–22). In schemes based on platinum and taxane, the response rates were 30–50% (23–34), and reported response rates were >50% (up to 79%) in Phase II trials, which included a considerable number of patients at low risk (35–40), who were present in the minority in the present study. Of the study subjects, >85% received treatment regimens based on platinum. It is important to note that, prior to 2004, the use of taxanes was not common, and several of the schemes that were in use prior to this date are now useless. The median OS was 14.2 months, whereas the PFS was 7.1 months, also consistent with the trials. Approximately 40% of the patients received more than one line of treatment. At present, there is no set pattern of second-line chemotherapy in CUP. The use of multiple lines of treatment is subject to an appropriate assessment being made of the patient, and its recommendation is questionable; therefore, it was reserved for patients who had a good response rate with a previous scheme, and who were of excellent functional status. The weighting of risk-benefit and economic impact were not objectives of the present study. Regarding the clinicopathological factors of poor response to treatment, age, gender, ECOG, histology, grade of differentiation, number and location of metastases, elevation of tumor markers, elevated LDH and decreased albumin were analyzed. The results demonstrated that, in univariate analysis of response to treatment, the significant factors were ECOG-1, normal LDH and adenocarcinoma histology for a greater response to treatment; however, when performing multivariate logistic regression analysis, only ECOG proved to be an independent predictor of the response to treatment. Similarly, when analyzing the prognostic factors for OS and PFS, the ECOG was the only independent factor for these two characteristics. The other variables analyzed did not reach a statistically significant P-value. It should be noted that, according to the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the level of LDH was identified at the limit of statistical significance (P=0.054), and this may be due to the fact that patients were not stratified according to elevated levels of this protein. The ECOG as a predictor of a poor response to cytotoxic therapy in patients with CUP has been referred to in numerous studies that had similar aims (8,10,12,22,41–44).

Several studies have identified prognostic factors associated with survival in patients with unknown primary cancer. However, there is, thus far, a solid classification system in place that enables the stratification of patients according to these characteristics in risk groups, since the groups of patients studied tend to be heterogeneous, and therefore the factors mentioned are inconsistent. The present study has revealed specific aspects of heterogeneity of the patients, including multiple histologies, and the grade of differentiation and application of various treatments. Adenocarcinoma and squamous cell histologies yielded higher rates of CR and PR for adenocarcinoma (41.7 and 48.5%, respectively) compared with a CR of 33.3% and a PR of 30.3% for squamous cell carcinoma. Similarly, a poor differentiation grade represented >60% of cases of objective responses to treatment. However, on performing the univariate analysis, none of these variables were revealed to be statistically significant. The data collection in retrospective studies, such as the present example, has a number of disadvantages: Usually, there is bias in the catch; there are not properly specified degrees of toxicity in all cases; and there is the possibility of errors emerging as a consequence of subjective assessment.

It would be imperative in subsequent prospective analyses to reduce the heterogeneity of the study population, excluding patients from well-defined subgroups with good prognosis with specific treatment indications, and yet without losing sight of those patients from established groups of potentially curable disease or under good control, as lymphomas, germ cell tumors, breast cancer or neuroendocrine tumors (45). At present, there are no Phase III studies comparing systemic treatment with best supportive care in patients with unfavorable risk factors. Prospective clinical trials are required to establish the optimal treatment for each patient, and to clearly define the group of patients who will benefit from cytotoxic treatment.

Treatment of patients with CUP remains a challenge for oncology, and requires a multidisciplinary approach. The objective should be focused on preventing the requirement for empirical management, in this context, with the advent of molecular and genetic profiles that are currently under study for this complex neoplasm (46–51) and the development of therapeutics based on a combination of molecular biology, microarray and immunohistochemistry approaches, and therefore clinical and pathological factors will have an essential role in the management of these patients.

Taken together, the ECOG performance status is an independent predictor of poor response to chemotherapy, and lower OS and PFS in patients with CUP.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the National Medical Center ‘Century XXI’, IMSS, México for their support.

References

- 1.Pavlidis N, Fizazi K. Carcinoma of unknown primary (CUP) Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2009;69:271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavlidis N, Briasoulis E, Hainsworth J, Greco F. Diagnostic and therapeutic management of cancer of an unknown primary. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1990–2005. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00547-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krementz ET, Cerise EJ, Foster DS, Morgan L., Jr Metastases of undetermined source. Curr Pobl Cancer. 1979;4:4–37. doi: 10.1016/s0147-0272(79)80019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosetti C, Rodríguez T, Chatenoud L, Bertuccio P, Levi F, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Trends in cancer mortality in Mexico, 1981–2007. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2011;20:355–363. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32834653c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pentheroukadis G, Briasoulis E, Pavlidis N. Cancer of unknown primary site: Missing primary or missing biology? Oncologist. 2007;12:418–425. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-4-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sporn JR, Greenberg BR. Empirical chemotherapy for adenocarcinoma of unknown primary site. Semin Oncol. 1993;20:261–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Culine S. Prognostic factors in unknown primary cancer. Semin Oncol. 2009;36:60–64. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbruzzese JL, Abbruzzese MC, Hess KR, Raber MN, Lenzi R, Frost P. Unknown primary carcinoma: Natural history and prognostic factors in 657 consecutive patients. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1272–1280. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.6.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hess KR, Abbruzzese MC, Lenzi R, Raber MN, Abbruzzese JL. Classification and regression tree analysis of 1,000 consecutive patients with unknown primary carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:3403–3410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lortholary A, Abadie-Lacourtoisie S, Guérin O, Mege M, Rauglaudre GD, Gamelin E. Cancers of unknown origin: 311 cases. Bull Cancer. 2001;88:619–627. (In French) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Culine S, Kramar A, Saghatchian M, Bugat R, Lesimple T, Lortholary A, Merrouche Y, Laplanche A, Fizazi K. French Study Group on Carcinomas of Unknown Primary: Development and validation of a prognostic model to predict the length of survival in patients with carcinomas of an unknown primary site. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4679–4683. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seve P, Ray-Coquard I, Trillet-Lenoir V, Sawyer M, Hanson J, Broussolle C, Negrier S, Dumontet C, Mackey JR. Low serum albumin levels and liver metastases are powerful prognostic markers for survival in patients with carcinomas of unknown primary site. Cancer. 2006;107:2698–2705. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lenzi R, Abbruzzese J, Amato R, et al. Cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil and follinic acid for the treatment of carcinoma of unknown primary: A phase II study. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1991;10:301. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farrugia DC, Norman AR, Nicolson MC, Gore M, Bolodeoku ED, Webb A, Cunningham D. Unknown primary carcinoma: Randomized studies are needed to identify optimal treatments and their benefits. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:2256–2261. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(96)00264-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rigg A, Cunningham D, Gore M, Hill M, O'Brien M, Nicolson M, Chang J, Watson M, Norman A, Hill A, Oates J, et al. A phase I/II study of leucovorin, carboplatin and 5-fluorouracil (LCF) in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary site or advanced oesophagogastric/pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:101–105. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pavlidis N, Kosmidis P, Skarlos D, Brissoulis E, Beer M, Theoharis D, Bafaloukos D, Maraveyas A, Fountzilas G. Subsets of tumors responsive to cisplatin or carboplatin combinatios in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary site. A hellenic cooperative oncology group study. Ann Oncol. 1992;3:631–634. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Briasoulis E, Tsavaris N, Fountzilas G, Athanasiadis A, Kosmidis P, Bafaloukos D, Skarlos D, Samantas E, Pavlidis N. Combination regimen with carboplatin, epirubicin and etoposide in metastatic carcinomas of unknown primary site: A Hellenic Co-oncology group phase II study. Oncology. 1998;55:426–430. doi: 10.1159/000011890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warner E, Goel R, Chang J, Chow W, Verma S, Dancey J, Franssen E, Dulude H, Girouard M, Correia J, Gallant G. A mulicenter phase II study of carboplatin and prolonged oral etoposide in the treatment of cancer of unknown primary site (CUPS) Br J Cancer. 1998;77:2376–2380. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voog E, Merrouche Y, Trillet-Lenoir V, Lasset C, Peaud PY, Rebattu P, Negrier S. Multicentric phase II study of cisplatin and etoposide in patients with metastatic carcinoma of unknown primary. Am J Clin Oncol. 2000;23:614–616. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200012000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macdonald AG, Nicolson MC, Samuel LM, Hutcheon AW, Ahmed FY. A phase II study of mitomycin C, cisplatin and continuous infusion 5-fluorouracil (MCF) in the treatment of patients with carcinoma of unknown primary site. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:1238–1242. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piga A, Gesuita R, Catalano V, Nortilli R, Getto G, Cardillo F, Giorgi F, Riva N, Porfiri E, Montironi R, et al. Identification of clinical prognostic factors in patients with unknown primary tumors treated with a platinum-based combination. Oncology. 2005;69:135–144. doi: 10.1159/000087837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pittman KB, Olver IN, Koczwara B, Kotasek D, Patterson WK, Keefe DM, Karapetis CS, Parnis FX, Moldovan S, Yeend SJ, et al. Gemcitabine and carboplatin in carcinoma of unknown primary site: A phase II Adelaide cancer trials and education collaborative study. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1309–1313. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hainsworth JD, Erland JB, Kalman LA, Schreeder MT, Greco FA. Carcinoma of unknown primary site: Treatment with 1-h paclitaxel, carboplatin, and extended-schedule etoposide. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2385–2393. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Briasoulis E, Kalofonos H, Bafaloukos D, Samantas E, Fountzilas G, Xiros N, Skarlos D, Christodoulou C, Kosmidis P, Pavlidis N. Carboplatin plus paclitaxel in unknown primary carcinoma: A phase II study. The Hellenic cooperative oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3101–3117. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greco FA, Burris HA, III, Erland JB, Gray JR, Kalman LA, Schreeder MT, Hainsworth JD. Carcinoma of unknown primary site. Cancer. 2000;89:2655–2660. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001215)89:12<2655::AID-CNCR19>3.3.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouleuc C, Saghatchian M, Di Tullio L, Louvet CH, Levy E, Di Palma M, et al. A multicenter phase II study of docetaxel and cisplatin in the treatment of cancer of unknown primary site. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2001;137b:2298. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Darby A, Richardson L, Nokes L, Harvey M, Hassan A, Iveson T. Phase II study of single agent docetaxel in carcinoma of unknown primary site. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2001;100b:2151. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gothelf A, Daugaard G, Nelausen K. Paclitaxel, cisplatin and gemcitabine in the treatment of unknown primary tumours, a phase II study. ESMO. 2002;25:88. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greco FA, Burris HA, III, Litchy S, Barton JH, Bradof JE, Richards P, Scullin DC, Jr, Erland JB, Morrissey LH, Hainsworth JD. Gemcitabine, carboplatin, and paclitaxel for patients with carcinoma of unknown primary site: A Minnie pearl cancer research network study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1651–1656. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.6.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greco FA, Rodriguez GI, Shaffer DW, Hermann R, Litchy S, Yardley DA, Burris HA, III, Morrissey LH, Erland JB, Hainsworth JD. Carcinoma of unknown primary site: Sequential treatment with paclitaxel/carboplatin/etoposide and gemcitabine/irinotecan: A Minnie pearl cancer research network phase II trial. Oncologist. 2004;9:644–652. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-6-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park YH, Ryoo BY, Choi SJ, Yang SH, Kim HT. A phase II study of paclitaxel plus cisplatin chemotherapy in an unfavourable group of patients with cancer of unknown primary site. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:681–685. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyh124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pouessel D, Culine S, Becht C, Ychou M, Romieu G, Fabbro M, Cupissol D, Pinguet F. Gemcitabine and docetaxel as front-line chemotherapy in patients with carcinoma of an unknown primary site. Cancer. 2004;100:1257–1261. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El-Rayes BF, Shields AF, Zalupski M, Heilbrum LK, Jain V, Terry D, Ferris AM, Philip PA. A phase II study of carboplatin and paclitaxel in adenocarcinoma of unknown primary. Am J Clin Oncol. 2005;28:152–156. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000142590.70472.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hainsworth JD, Spigel DR, Litchy S, Greco FA. Phase II trial of paclitaxel, carboplatin, and etoposide in advanced poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma: A Minnie pearl cancer research network study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3548–3554. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.0575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Gaast A, Verweij J, Henzen-Logmans SC, Rodenburg CJ, Stoter G. Carcinoma of unknown primary: Identification of a treatable subset? Ann Oncol. 1990;1:119–122. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a057688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hainsworth JD, Johnson DH, Greco FA. The role of etoposide in the treatment of poorly differenciated carcinoma of unknown primary site. Cancer. 1991;67:S310–S314. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910101)67:1+<310::AID-CNCR2820671317>3.0.CO;2-9. (Suppl 1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khansur T, Allred C, Little D, Anand V. Cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil for metastatic squamous cell carcinoma from unknown primary. Cancer Invest. 1995;13:263–266. doi: 10.3109/07357909509094459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greco FA, Vaughn WK, Hainsworth JD. Advanced poorly differenciated carcinoma of unknown primary site: Recognition of a treatable syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:547–553. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-104-4-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Falkson CI, Cohen GL. Mitomycin, epirubicin and cisplatin versus mitomycin-C alone as therapy for carcinoma ok unknown primary origin. Oncology. 1998;55:116–121. doi: 10.1159/000011845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guardiola E, Pivot X, Tchicknavorian X, Magne N, Otto J, Thyss A, Schneider M. Combination of cisplatin-doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide in adenocarcinoma of unknown primary site: A phase II trial. Am J Clin Oncol. 2001;24:372–375. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200108000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Gaast A, Verweij J, Planting AS, Hop WC, Stoter G. Simple prognostic model to predict survival in patients with undifferentiated carcinoma of unknown primary site. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1720–1725. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.7.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kambhu SA, Kelsen DP, Fiore J, Niedzwiecki D, Chapman D, Vinciguerra V, Rosenbluth R. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of unknown primary site. Prognostic variables and treatment results. Am J Clin Oncol. 1990;13:55–60. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199002000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seve P, Sawyer M, Hanson J, Broussolle C, Dumontet C, Mackey JR. The influence of comorbidities, age, and performance status on the prognosis and treatment of patients with metastatic carcinoma of unknown primary site: A population-based study. Cancer. 2006;106:2058–2066. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pasterz R, Savaraj N, Burgess M. Prognostic factors in metastatic carcinoma of unknown primary. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4:1652–1657. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.11.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lenzi R, Hess KR, Abbruzzese MC, Raber MN, Ordoñez NG, Abbruzzese JL. Poorly differenciated carcinoma and poorly differenciated adenocarcinoma of unknown origin: Favorable subsets of patients with unknown-primary carcinoma? J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2056–2066. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.5.2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Varadhachary GR, Talantov D, Raber MN, Meng C, Hess KR, Jatkoe T, Lenzi R, Spigel DR, Wang Y, Greco FA, et al. Molecular profiling of carcinoma of unknown primary and correlation with clinical evaluation. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4442–4448. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pentheroukadis G, Golfinopoulos V, Pavlidis N. Swithing benchmarks in cancer of unknown primary: From autopsy to microarray. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2026–2036. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fizazi K. Treatment of patients with specific subsets of carcinoma of an unknown primary site. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:x177–x180. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl256. (Suppl 10) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Varadhachary GR, Greco FA. Overview of patient management and future directions in unknown primary carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2009;36:75–80. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Viale G, Mastropasqua MG. Diagnostic and therapeutic management of carcinoma of unknown primary: Histopathological and molecular diagnosis. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:x163–x167. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl254. (Suppl 10) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van de Wouw AJ, Jansen RL, Speel EJ, Hillen HF. The unknown biology of the unknown primary tumour: A literature review. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:191–196. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]