Abstract

Background:

Dependence on high-dose benzodiazepines (BZDs) is well known and discontinuation attempts are generally unsuccessful. A well established protocol for high-dose BZD withdrawal management is lacking. We present the case of withdrawal from high-dose lorazepam (>20 mg daily) in an unemployed 35-year-old male outpatient through agonist substitution with long-acting clonazepam and electronic monitoring over 28 weeks.

Methods:

All medicines were repacked into weekly 7 × 4 cavity multidose punch cards with an electronic monitoring system. The prescribed daily dosages of BZDs were translated into an optimal number of daily tablets, divided into up to four units of use. Withdrawal was achieved by individual leftover of a small quantity of BZDs that was placed in a separate compartment. Feedback with visualization of intake over the past week was given during weekly psychosocial sessions.

Results:

Stepwise reduction was obtained by reducing the mg content of the cavities proportionally to the leftovers, keeping the number of cavities in order to maintain regular intake behavior, and to determine the dosage decrease. At week 28, the primary objectives were achieved, that is, lorazepam reduction to 5 mg daily and cannabis abstinence. Therapy was continued using multidrug punch cards without electronic monitoring to maintain the management system. At week 48, a smaller size weekly pill organizer with detachable daily containers was dispensed. At week 68, the patient’s therapy was constant with 1.5 mg clonazepam + 5 mg lorazepam daily for anxiety symptoms and the last steps of withdrawal were started.

Conclusions:

Several key factors led to successful withdrawal from high-dose BZD in this outpatient, such as the use of weekly punch cards coupled with electronic monitoring, the patient’s empowerment over the withdrawal process, and the collaboration of several healthcare professionals. The major implication for clinical care is reduction by following the leftovers, and not a diktat from the healthcare professionals.

Keywords: addiction, benzodiazepine, community pharmacy, electronic monitoring, multidrug punch card, printed electronics, substance withdrawal

Introduction

Benzodiazepines (BZDs) are psychoactive drugs prescribed as anxiolytics, sedatives, hypnotics, anticonvulsants, and skeletal muscle relaxants since the 1960/1970s.1 Due to their wide range of action and their low toxicity compared with other drugs, BZDs became one of the most commonly used and misused drug classes worldwide.2 For Switzerland, a national pharmacy claims analysis3 performed in 2006 calculated a 1-year prevalence for BZD prescriptions of 14.5%, similar to other countries.4–6 In the same study, 56% of patients obtained repeat BZD prescriptions for a treatment duration exceeding 90 days.3 In 2014, among the general Swiss population, 253,000 citizens were using BZDs as tranquilizers or for sleeping problems, mostly in women aged over 70 years.7

BZDs are potentially addictive. The most widespread form of BZD dependence is iatrogenic, that is, patients have been prescribed BZDs to treat underlying conditions8 and then progress to long-term use (>4–8 weeks) with optional dose increase. In 2014, the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health published recommendations for restricted prescription and dispensing of BZDs in daily practice.9 However, prescription habits do not seem to have changed yet.10

The overall objective of BZD withdrawal consists of total abstinence, as discontinuation mostly improves psychomotor and neurocognitive functioning, particularly in older people.11 A slow dose reduction is recommended9 but guidelines are imprecise. Strategies include gradual dosage tapering and psychosocial support12 after switching to an equivalent dose of a long-acting BZD [such as diazepam (Valium, Roche Pharma Schweiz) or clonazepam (Rivotril, Roche Pharma Schweiz)]. Agonist replacement therapy with the BZD clonazepam is a safe and efficacious method.13 After discharge, the common recommendations for tapering in outpatients is a slow decrease over several weeks14 but the optimal rate of tapering is unclear. Weekly reductions are proposed over 4–10 weeks; they should not exceed 25% per week15 or be 10–25% of the dose that had been previously taken16,17 or 10% every 1–2 weeks.18 Outpatient withdrawal has proven feasible.19,20 The success of pharmacological interventions for BZD dependence management is poor to moderate.21 Nevertheless, the outcome of successful BZD withdrawal is gratifying, both in terms of improved functioning and economic benefits.

To our knowledge, there is no well established protocol for high-dose BZD withdrawal management. In a qualitative study of patients’ views on high-dose BZD withdrawal, patients frequently reported that they were unable to take their medication as prescribed during the process of slow dose reduction.22 The complicated and unpredictable perception of the withdrawal was the trigger for high rates of unsuccessful discontinuation attempts. This situation caused a vicious circle for the patient of personal frustration, disappointment and dissatisfaction that often led to a decision to enter inpatient treatment, which, at the same time, was perceived as limiting personal freedom making it harder to overcome the dependence. Interventions able to increase patients’ freedom, autonomy and motivation seem crucial to help them attain their goals in outpatient settings. However, treatment retention is poor and long-term abstinence is rare in most patients.14

The new technology used in this study23 enables the electronic monitoring of individualized polypharmacy. The Polypharmacy Electronic Monitoring System (POEMS) is composed of printed electronics in a clear, self-adhesive paper film that can be affixed together with a chip on the back of a multidose punch card (also termed ‘multicompartment compliance aids’ or ‘dose administration aids’). This blister-type repackaging storage system is prepared in community pharmacies for organizing solid drugs prescribed to an individual, usually for 1 week.24 The loops of conductive wires measure the electrical resistance and record the time of its changes when a loop is broken, that is when a cavity is emptied and medication is taken. The data are transferred via a wireless communication device to a web-based database.

In a prior study, patients reported that the visualization of the electronically recorded medicine intake that was used during the feedback sessions helped them to gain self confidence.25 We present an illustrative case of withdrawal from high-dose BZDs with electronic monitoring of polypharmacy and corresponding feedback in an outpatient setting using multiprofessional team care. This report does not require ethics approval according to Swiss law (declaration of good standing). The patient provided written informed consent before the study for publication of his history in a de-identified form.

Case description

Our patient is a single, 35-year-old, white man, with a university degree in law who has never been employed. He lives independently (and alone) in a one-room apartment in Basel. He is socially isolated and gets social welfare. He has a longstanding history of misuse of cannabis and the BZD lorazepam for recurrent sleeping problems. He has been treated for depression with alternate use of escitalopram, trazadone and mirtazapine (strength unknown, start and length of treatments unknown) and stopped therapy because of marked side effects. The last episode of depression occurred in October 2014. The patient self medicated with lorazepam for anxiety and depression symptoms. He has bought lorazepam for years on the internet. During the past 12 months, his consumption has risen to 20–25 mg lorazepam daily. The patient has tried several times unsuccessfully to overcome his dependence and has developed subjectively strong withdrawal symptoms such as sweating, trembling and sleeplessness. After a further attempt to withdraw lorazepam that resulted in two consecutive sleepless nights, the patient was admitted to a psychiatric clinic on his own request on 18 December 2014 with the intention to reduce lorazepam and to withdraw cannabis consumption. He showed clearly depressive traits, inner anxiety and weak emotional tension, was worried about the future and reported inferiority feelings. His long-lasting unemployment bothered him. He had pronounced sleeping disorders with an inability to fall asleep. Standard medical and laboratory examinations did not show anything besides positive cannabis and BZD testing. During his hospital stay, clonazepam was titrated to reach 16 mg daily (4 – 4 – 4 – 4) with the aim of replacing lorazepam, to be subsequently reduced. Depressive symptomatology reached a mild expression (Beck Depression Inventory26 score of 18). Because of negative experiences, however, the patient declined an antidepressant for his depression. Therefore, a combination of motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy was delivered in individual sessions in which problem behaviors and problem thinking were identified, prioritized and specifically addressed with a range of techniques. To enhance the patient’s motivation to change his BZD and cannabis use behavior, a decisional analysis was done whereby the patient was assisted to critically examine the advantages and the disadvantages of continued drug use. Furthermore, the patient was instructed in the use of substance-related coping skills. These included techniques for managing urges and cravings, recognizing triggers for drug use and developing personal strategies for either avoiding or dealing with such triggers, managing withdrawal symptoms, and learning relapse prevention strategies. The therapeutic program also instructed on general coping skills, including techniques for coping with negative affect and stress, assertiveness and communication skills training, and relaxation skills. Motivational enhancement therapy (that is motivational interviewing with among others the use of open-ended questions, reflective listening, affirmative style and setting goals) was the method of choice to enhance personal motivation. The patient actively took part in psychotherapy sessions. Cessation of cannabis smoking and its advantages were thematized simultaneously with BZD withdrawal at each session, comparable with a high-intensity intervention.27 Urinalysis was not performed because verification is not judged compatible with the motivational nature of the behavioral therapy. Cannabis use was reduced from 12 to 3 joints daily. Complete withdrawal from cannabis and from lorazepam was not undertaken for fear of depressive episodes. The patient expressed the wish to continue to reduce lorazepam in an ambulatory setting and was ambivalent about quitting cannabis consumption. He was aware that entire withdrawal could take 1–2 years. The patient accepted a seamless referral to the Division of Substance Use Disorders. At discharge on 15 January 2015, the patient was prescribed clonazepam 15 mg daily (4 – 3 – 4 – 4) and lorazepam 5 mg in the evening. He agreed to meet weekly with a psychotherapist and to obtain 7-day rations of medication. During these weekly consultations, the patient reported having repeated cravings for lorazepam, mostly in the evening when he had thoughts about his unemployment and his future. He regularly takes 7.5 mg lorazepam to sleep. The clonazepam intake in the morning is erratic because of tiredness. The search for employment is impossible. On 12 February 2015, night-time urinary incontinence occurred which the patient attributed to clonazepam. Immediate reduction was self implemented within 1 week to clonazepam 8 mg daily and lorazepam 2.5 mg approximately 2 h after the last clonazepam intake. Incontinence and craving vanished. On 18 February 2015, the psychotherapist offered the patient the option of getting his medication in weekly multidrug punch cards with electronic monitoring so that he could visualize advances in the withdrawal process. The patient agreed to pick up his medication every week from the community pharmacy, immediately after his visit with the psychiatrist. The two buildings are 150 m apart. The pharmacist repackaged all the medication in a weekly punch card with 7 × 4 cavities and POEMS. The content of the cavities was discussed with the psychotherapist after each consultation. The prescribed daily dosages of BZDs were translated into an optimal number of daily tablets, divided into several units of use, and placed into the maximum number of punch card cavities. For individual reduction of the dosage, one small amount was stored separately to be taken on demand (see Table 1). The patient was advised to take his tablets at the time of his choosing. Parallel consumption was not controlled for, but specifically addressed during the weekly individual sessions with the psychotherapist. Cannabis withdrawal remained a primary goal.

Table 1.

Two days of the regimen at week 20 (16–22 July 2015) with prescribed dosage of clonazepam (CLO) 4 mg daily + lorazepam (LOR) 5 mg daily plus one additional tablet of lorazepam 2.5 mg weekly, supplied as clonazepam tablets 2 mg (white tablet with cross-score break line; one in the first cavity) and 0.5 mg (beige tablet with breakbar; two in the first cavity and two in the second cavity), and as lorazepam 2.5 mg (yellow tablet with breakbar; two in the third cavity and one in the last cavity of the last raw).

| CLO 1×2mg + 2x0.5mg |

CLO 2×0.5mg on demand |

LOR 2×2.5 mg |

LOR 1×2.5mg on demand |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tuesday 21 July 2015 |

|

|||

| Wednesday 22 July 2015 | ||||

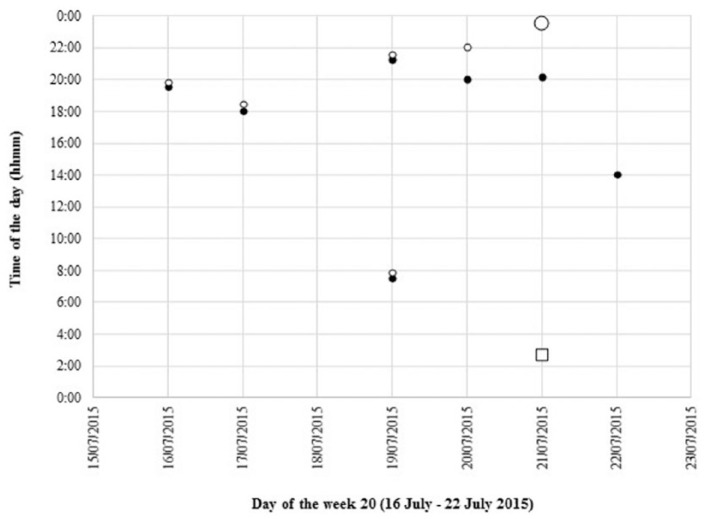

Starting on 4 March 2015, a total of 196 days of therapy were dispensed in 45 electronic punch cards over 28 weeks until 16 September 2015, with two punch cards per week during the first 17 weeks. Fourteen days were not recorded due to technical problems (7.1% missed data). All dispensed punch cards were returned. During the weekly psychosocial sessions, graphs of the last week’s intakes were presented to the patient and discussed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the intakes of week 20 (16 July–22 July 2015), filled with clonazepam (black circle), lorazepam (white circle). The white square indicates an additional lorazepam tablet (one per week); a larger circle indicates double intake.

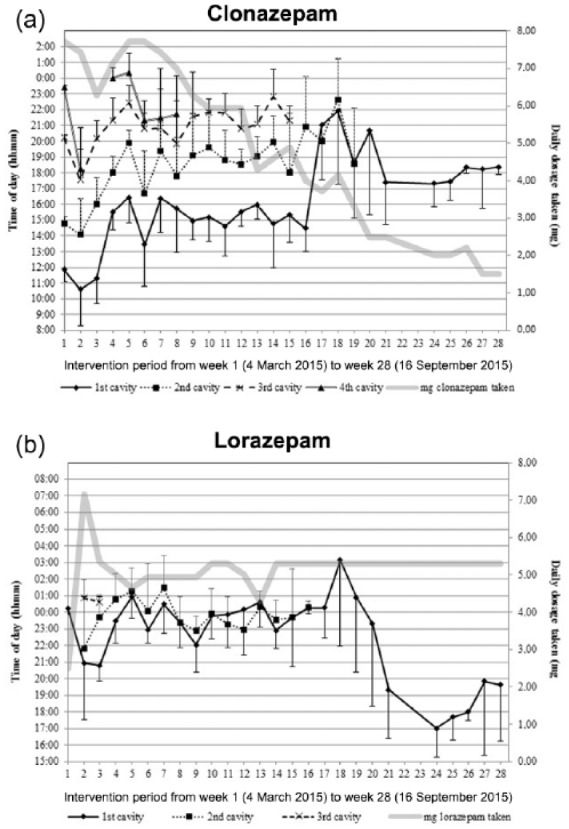

Over the 28 weeks of monitoring, dispensed clonazepam was reduced from 8 to 2 mg daily. The amount of clonazepam taken was always less due to leftovers, beginning with doses from the fourth cavities [week 2–3 (2 mg daily), week 9 (1 mg daily); see Figure 2(a)] to the second cavities [from week 20 onwards (0.5 mg daily)]. In parallel, the number of cavities with clonazepam tablets available decreased from three [week 9–15 (7–5 mg available)], to two [week 16 onwards (5–2 mg available)]. Clonazepam intake ended at 1.5 mg daily (80% reduction).

Figure 2.

Mean weekly intake time of the content of the different punch card cavities filled with clonazepam (a) and lorazepam (b) over 28 weeks. The daily amount of benzodiazepine taken is indicated with a bold grey line. The four different cavities per punch card are marked with a bold line (first cavity —); spotted line (2nd cavity …); dotted line (3rd cavity –); double line (4th cavity ==). Standard deviations are given as half bars (minus for first cavities; plus for the other cavities).

One single daily dose of 2.5 mg lorazepam during week 1 turned out to be insufficient and dosage was tripled and distributed into three cavities for weeks 2 and 3 [Figure 2(b)]. The third cavity turned out to be superfluous and two cavities with one tablet of lorazepam 2.5 mg each were dispensed from week 4 onwards. Lorazepam was dispensed and taken in a similar pattern as clonazepam, and was reduced from 7.5 to 5 mg daily plus one additional tablet of lorazepam 2.5 mg weekly from week 10 onwards. At week 16, the patient achieved complete cannabis withdrawal on his own. At week 20, the patient found a job.

On 15 September 2015 (week 28) the patient ended with 6.5 mg BZDs daily and the primary objectives, that is lorazepam reduction and entire cannabis withdrawal, were achieved. Electronic monitoring was removed on the patient’s request but dispensing of therapy in multidrug punch cards was continued to maintain the management system. On 4 February 2016 (week 48), a smaller size weekly pill organizer with detachable daily containers was dispensed. On 15 September 2016 (week 80), mirtazapine 15 mg once daily in the evening was started. The patient’s therapy was constant with 1.5 mg clonazepam + 5 mg lorazepam daily for anxiety symptoms. At the time of writing this article (5 November 2016, week 90), the patient agreed to withdraw clonazepam and low-dose lorazepam within the next 6 months.

Discussion

In our exemplary case, the tapering speed was centered on the tablets the patient would and could intentionally leave over. To do so, the daily dosages of BZDs were divided into units of use with a small amount to be left over. Repackaging into multidose punch cards is the method of choice in this new approach. Further, immediate reinforcement is obtained at the sight of the leftover medication in its cavity in due course. The weekly psychosocial interventions included cognitive behavioral therapy by the psychiatrist and a brief intervention by the pharmacist each time the patient came in for his medication. The weekly feedback based on the intake graph enabled the psychiatrist to highlight and discuss deviant habits, to adjust treatment, to control the effect of the adjustment of the past week, to reinforce correct behavior and to continue dose reduction.28 Our study indicates that a longer time span with weekly sessions including interventions with feedback may result in a successful reduction of BZDs.

Our patient reported that viewing his intake behavior made him aware of his dependence and he was able to gradually gain confidence in himself and in the intervention. Moreover, electronic monitoring was seen as the way to materialize the withdrawal steps and to obtain control over the process. Self confidence started a domino effect with positive thoughts and changed the patient’s behavior toward a high adherence to the withdrawal schedule, reduced cannabis consumption and conscientious search for employment. The patient did not feel controlled by the electronic monitoring, but much more supported and finally empowered to make informed decisions such as cannabis abstinence. Moreover, deciding when to take medicine, and when to leave medicine over, increased the patient’s autonomy, and is synonymous with empowerment.29

Although our patient did not reach BZD abstinence after 28 weeks, our case is successful for several reasons. First, the switch from short-acting BZDs to a long-acting substance succeeded and was followed by a stepwise reduction, so that the total daily dose of BZDs could be reduced overall by 74% (from 125 to 33 mg, measured in diazepam equivalent). Second, the associated risk behavior such as cannabis consumption was diminished, and third, the burden of psychiatric symptoms was reduced so that our patient could find a job. Thus, after a phase of stabilization, the physician proposed tackling the next steps of further withdrawal, which was accepted by our patient after 90 weeks.

We acknowledge some limitations. First, pocket doses, that is the removal of doses in anticipation of intake outdoors and without the punch cards, were taken. This was noted by three or more removals being recorded at the same time, predominantly during the first weeks of monitoring. No adjustments were made for pocket dosing since no information was obtained on actual intake. The analysis of the data without pocket doses did not change the results substantially, demonstrating their marginal effect on the overall results. Second, some cavities were filled with two or more tablets. When the patient left some of these tablets over, he placed the surplus back into the opened cavity. However, during transportation, some tablets could have been lost, masking untaken tablets. Third, as is true of any indirect method of adherence measure, electronic monitoring does not demonstrate ingestion of the dispensed medicine. However, exceptional and sustained commitment is required to create a false record of good adherence.30 Thus, we can affirm that the doses were taken immediately after their removal, except for pocket doses.

Implication for clinical care

The success our patient achieved in withdrawing from high-dose lorazepam may be due to the multidimensional intervention composed of a new technology (electronic monitoring), several healthcare providers in collaboration (hospital and general physicians, psychiatrist, pharmacist) and the empowerment of the patient. The daily BZD dosages divided into portions and placed in the maximum number of cavities of a multidose punch card, with a small amount to be left over, allowed reduction of the doses without changing the dosing intervals, maintaining the intake habits and following the speed of the patient. When time is perceived as an empowering factor, successful withdrawal is possible. Because BZD misuse and dependence is widespread in the general elderly population, representing a public health problem,31 our approach with repackaging of polypharmacy inclusive of BZD with subsequent slow tapering could constitute a novel and promising method. Further studies are needed in this area.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the staff of the pharmacy Apotheke Hersberger am Spalebärg for their support.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Hèctor R. Loscertales, Pharmaceutical Care Research Group, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Valerie Wentzky, Pharmaceutical Care Research Group, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland.

Kenneth Dürsteler, Division of Addictive Disorders, University of Basel Psychiatric Clinics, Basel, Switzerland.

Johannes Strasser, Division of Addictive Disorders, University of Basel Psychiatric Clinics, Basel, Switzerland.

Kurt E. Hersberger, Pharmaceutical Care Research Group, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Isabelle Arnet, Pharmaceutical Care Research Group, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Basel, Klingelbergstrasse 50, 4056 Basel, Switzerland.

References

- 1. Lader M. History of benzodiazepine dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat 1991; 8: 53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O’Brien C. Benzodiazepine use, abuse, and dependence. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66(Suppl. 2): 28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Petitjean S, Ladewig D, Meier CR, et al. Benzodiazepine prescribing to the Swiss adult population: results from a national survey of community pharmacies. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2007; 22: 292–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lagnaoui R, Depont F, Fourrier A, et al. Patterns and correlates of benzodiazepine use in the French general population. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2004; 60: 523–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Windle A, Elliot E, Duszynski K, et al. Benzodiazepine prescribing in elderly Australian general practice patients. Aust N Z J Public Health 2007; 31: 379–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spanemberg L, Nogueira EL, Belem Da, Silva CT, et al. High prevalence and prescription of benzodiazepines for elderly: data from psychiatric consultation to patients from an emergency room of a general hospital. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2011; 33: 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Corolar (Continuous Rolling Survey of Addictive Behaviours and Related Risks). Häufigkeit und Dauer der Einnahme von Schlaf- und Beruhigungsmitteln, nach Geschlecht und Alter, www.suchtmonitoring.ch (2014, accessed 19 August 2016).

- 8. Minaya O, Fresán A, Cortes-Lopez JL, et al. The Benzodiazepine Dependence Questionnaire (BDEPQ): validity and reliability in Mexican psychiatric patients. Addict Behav 2011; 36: 874–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bundesamt für Gesundheit BAG. Leitgedanken: Praxis Benzodiazepine und ähnliche Medikamente, www.bag.admin.ch/themen/drogen/00042/00629/00798 (2014, accessed 19 August 2016).

- 10. Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen SRF. Benzodiazepine - Sucht auf Rezept. Sendung PULS, podcast from 16 February 2016, www.srf.ch/sendungen/puls/lifestyle/benzodiazepine-sucht-auf-rezept (last accessed 23 August 2016).

- 11. Lader M, Tylee A, Donoghue J. Withdrawing benzodiazepines in primary care. CNS Drugs 2009; 23: 19–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ashton H. The diagnosis and management of benzodiazepine dependence. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2005; 18: 249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Patterson JF. Withdrawal from alprazolam dependency using clonazepam: clinical observations. J Clin Psychiatry 1990; 51(Suppl.): 47–49; discussion 50–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weaver MF. Prescription sedative misuse and abuse. Yale J Biol Med 2015; 88: 247–256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Federal Bureau of Prisons. Detoxification of chemically dependent inmates - Clinical practice guidelines, www.bop.gov/resources/health_care_mngmt.jsp (2014, accessed 7 May 2016).

- 16. Janhsen K, Roser P, Hoffmann K. The problems of long-term treatment with benzodiazepines and related substances. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2015; 112: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. IG Netzwerk Praxis Suchtmedizin Schweiz. Online Handbuch, www.praxis-suchtmedizin.ch (accessed 19 August 2016).

- 18. Kenny P, Swan A, Berends L, et al. Alcohol and other drug withdrawal: practice guidelines. chapter 12: benzodiazepine withdrawal, www.dacas.org.au/Clinical_Resources/Clinical_Guidelines/Benzodiazepine_withdrawal_guidelines.aspx (2009, accessed 19 August 2016).

- 19. Granato P, Shreekumar V, Fontaine A, et al. Original and simple protocol for withdrawal of benzodiazepines to achieve sustained remission. O J Psych 2016; 6: 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vicens C, Sempere E, Bejarano F, et al. Efficacy of two interventions on the discontinuation of benzodiazepines in long-term users: 36-month follow-up of a cluster randomised trial in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2016; 66: e85–e91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Denis C, Fatseas M, Lavie E, et al. Pharmacological interventions for benzodiazepine mono-dependence management in outpatient settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 3: CD005194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liebrenz M, Gehring MT, Buadze A, et al. High-dose benzodiazepine dependence: a qualitative study of patients’ perception on cessation and withdrawal. BMC Psychiatry 2015; 15: 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arnet I, Walter PN, Hersberger KE. Polymedication electronic monitoring system (POEMS) – a new technology for measuring adherence. Front Pharmacol 2013; 4: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Loscertales H, Modamio P, Lastra C, et al. Stability of enalapril repackaged into monitored dosage system. Curr Med Res Opin 2015; 31: 1915–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boeni F, Hersberger K, Arnet I. Success of a sustained pharmaceutical care service with electronic adherence monitoring in patient with diabetes over 12 months. BMJ Case Rep 2015. DOI: 10.1136/bcr-2014-208672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beck A, Steer R, Gk B. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gates P, Sabioni P, Copeland K, et al. Psychosocial interventions for cannabis use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 5: CD005336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vrijens B, Urquhart J, White D. Electronically monitored dosing histories can be used to develop a medication-taking habit and manage patient adherence. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2014; 7: 633–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Anderson RM, Funnell MM. Patient empowerment: myths and misconceptions. Patient Educ Couns 2010; 79: 277–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Urquhart J, De Klerk E. Contending paradigms for the interpretation of data on patient compliance with therapeutic drug regimens. Stat Med 1998; 17: 251–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Airagnes G, Pelissolo A, Lavallée M, et al. Benzodiazepine misuse in the elderly: risk factors, consequences, and management. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2016; 18: 89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]