Abstract

Trehalose is a non-reducing disaccharide that serves as the main sugar component of haemolymph in insects. Trehalose hydrolysis enzyme, called trehalase, is highly conserved from bacteria to humans. However, our understanding of the physiological role of trehalase remains incomplete. Here, we analyze the phenotypes of several Trehalase (Treh) loss-of-function alleles in a comparative manner in Drosophila. The previously reported mutant phenotype of Treh affecting neuroepithelial stem cell maintenance and differentiation in the optic lobe is caused by second-site alleles in addition to Treh. We further report that the survival rate of Treh null mutants is significantly influenced by dietary conditions. Treh mutant larvae are lethal not only on a low-sugar diet but also under low-protein diet conditions. A reduction in adaptation ability under poor food conditions in Treh mutants is mainly caused by the overaccumulation of trehalose rather than the loss of Treh, because the additional loss of Tps1 mitigates the lethal effect of Treh mutants. These results demonstrate that proper trehalose metabolism plays a critical role in adaptation under various environmental conditions.

Introduction

Living organisms can adapt to environmental changes through hormonal regulation and metabolic homeostasis. Sugars are primarily utilized in the metabolic production of ATP and carbon sources. In insects, blood sugar is stored as a non-reducing disaccharide trehalose and maintains glucose at low levels1–3. Trehalose is widely utilized as a sugar source in several organisms including bacteria, yeast, fungi, plants, and invertebrates3, 4. Because of its inert chemical properties, trehalose has the advantage of protecting organisms against several environmental stressors, such as desiccation and starvation5–7.

In Drosophila, trehalose is synthesized from glucose by trehalose-6-phosphate (Tre6P) synthase (Tps1) in the fat body and degraded to glucose by trehalase (Treh). Tps1 has two functionally distinct catalytic domains8, 9. The N-terminus trehalose-6-phosphate synthase (TPS) domain produces Tre6P from glycose-6-phophate (Glu-6P) and UDP-glucose. The C-terminus Tre6P phosphatase (TPP) domain de-phosphorylates Tre6P to generate trehalose. Treh is produced in two different forms via variations in alternative splicing (Flybase): a putative secreted form (sTreh), with a signal peptide at the N-terminus, and a cytoplasmic form (cTreh), without a signal peptide. The expression of sTreh is positively regulated by its own activity, whereas cTreh expression is regulated in a compensatory manner9. Tissue-specific expression patterns of two distinct forms suggest the systemic and local requirement of trehalose hydrolysis by Treh8. In the central nervous system, Treh is predominantly found in surface glia that forms the blood-brain barrier10. The local breakdown of trehalose and the following glycolysis in glia produces alanine and lactate. These C3 compounds are further metabolized in neurons, which is essential for neuronal survival10.

As in mammals, circulating sugar levels in Drosophila are regulated by the action of two endocrine hormones, insulin-like peptides (Dilps) and a glucagon-like peptide (Adipokinetic hormone, Akh). Indeed, feeding on dietary sugar immediately changes the levels of circulating sugar11. Elevated circulating glucose is taken up by several tissues in part through the action of insulin signaling, while starvation promotes lipid mobilization, the breakdown of glycogen, and gluconeogenesis partly through the action of glucagon signaling12–14. Genetic manipulation of the function of Dilps and Akh changes trehalose and glucose levels in the circulating haemolymph15, 16. Therefore, the mobilization of blood trehalose to glucose is critical for metabolic homeostasis. However, the physiological importance of circulating sugar metabolism in the adaptation to fluctuations in nutritional conditions remains unclear.

Recently, three groups, including ours, independently generated and reported the mutant alleles of Treh. However, the lethal phase is apparently different between mutant alleles. TALEN-induced null alleles of Treh are lethal at the first instar larval stage in homozygosity and in trans to a chromosomal deficiency10. However, we reported that CRISPR/Cas9-induced null alleles of Treh are lethal at the pupal stage in homozygosity and in trans to a chromosomal deficiency9. The other loss-of-function mutants of Treh that have a deletion/insertion within the intron region of the Treh gene exhibit disorganization in the optic lobe neuroepithelia in the central nervous system and are lethal at the wandering larval and pupal stages17.

Here, we report the genetic characterization of the mutant alleles of Treh under identical rearing conditions. We found that the reported mutant phenotype of Treh affecting neuroepithelial stem cell maintenance and differentiation in the optic lobe is caused by second-site alleles of lgl. We further found that loss of Treh leads to food-dependent larval lethality. A reduction in adaptation ability under poor food conditions in Treh mutants is caused by the overaccumulation of trehalose rather than the loss of Treh, because the additional loss of Tps1 mitigates the lethal effect of Treh mutants. These results demonstrate that trehalose metabolism plays a critical role in adaptation under various nutritional conditions in nature.

Results

Treh mutations do not cause disorganization of the optic lobe in the central nervous system

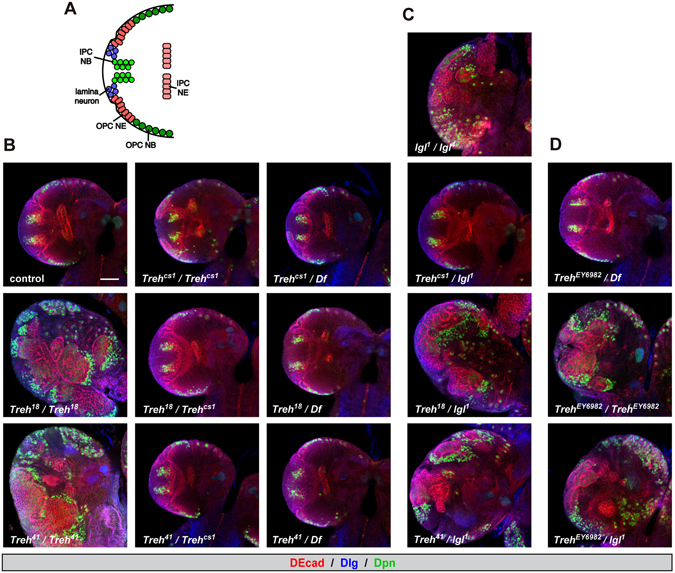

The central nervous system is an important tissue where circulating sugar mostly contributes to energy production. There are two proliferation centers in the larval optic lobe, namely, the outer proliferation center (OPC) and the inner proliferation center (IPC) (Fig. 1A)18, 19. OPC neuroepithelial cells differentiate into OPC neuroblasts and lamina neurons. IPC neuroepithelial cells are located in the inner and proximal side of the optic lobe and give rise to IPC neuroblasts, which are located on the distal side19, 20. It has been reported that Treh mutants exhibit disorganization of the optic lobe neuroepithelia in the central nervous system17. This phenotype is likely independent of its catalytic activity, because the increase in dietary glucose levels fails to rescue the mutant phenotype17.

Figure 1.

Treh mutants do not cause disorganization of the optic lobe in the central nervous system. (A) Schematic diagram of the frontal view of the larval optic lobe. Lamina neuron, OPC neuroepithelial cell (OPC NE), OPC neuroblast (OPC NE), IPC neuroepithelial cell (IPC NE), and IPC neuroblast (IPC NB) are shown. (B) Treh cs1 null mutants do not cause disorganization of the optic lobe in the central nervous system in homozygotes and in trans to a chromosomal deficiency. Wandering late-third instar larvae were stained for Deadpan (Dpn, green) to label neuroblasts and for Discs large (Dlg, blue) and DE-Cadherin (DE-cad, red) to label epithelial cells. Single medial confocal sections of the optic lobe for each genotype are shown. (C) Second site mutation(s) in the lgl locus is responsible for the disorganization phenotype of Treh 18 and Treh 41 mutants in the optic lobe neuroepithelia. (D) Original P-element insertion allele of Treh 18 and Treh 41 retains second site mutation(s) in the lgl locus. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Unlike the previous report, however, we found that CRISPR/Cas9-induced null alleles of Treh, named Treh cs1, did not display disorganization of the optic lobe neuroepithelia at the wandering third instar larval stage (Fig. 1B). Homozygous mutants of Treh 18 and Treh 41 that were used in the previous report indeed exhibited severe disorganization of the neuroepithelial cells (E-cadherin+ region) and medulla neuroblasts (Dpn+ region). However, transheterozygotes of Treh 18 or Treh 41 over the deficiency allele lacking the Treh locus or Treh cs1 had no obvious phenotype in the optic lobe neuroepithelia. These results suggest that second site mutation(s) are responsible for the observed defects in the optic lobe. Based on the morphological defects and the origin of the mutation on the second chromosome, we tested the contribution of the lgl gene locus. Transheterozygotes of lgl 1 over Treh 18 or Treh 41, but not over Treh cs1, displayed the overgrowth defects (Fig. 1C), indicating that second site mutation(s) are in the lgl locus. A high frequency second-site mutation in the lgl locus has been reported in the second chromosome stocks21. The original P-element insertion allele of Treh 18 and Treh 41 that was used for imprecise excision (Treh EY6928) displayed the identical phenotype (Fig. 1D), indicating that the original P-element allele retains a mutation in the lgl locus.

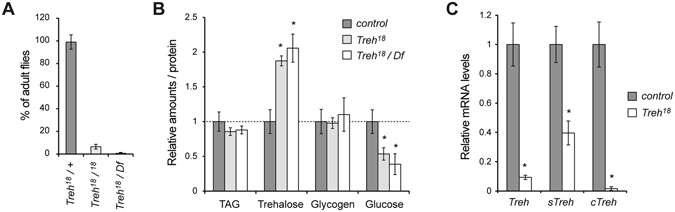

It should be noted, however, that transheterozygotes of Treh 18 or Treh 41 over the deficiency displayed pupal lethality (data not shown). We found that a backcrossed Treh 18 allele without lgl mutation(s) displayed no overgrowth in the optic lobe (data not shown) but exhibited pupal lethality with some escapers (Fig. 2A). Indeed, homozygotes of Treh 18 increased the levels of trehalose; however, the degree was less than that of Treh cs1 (Figs 2B and 3E). In addition, Treh 18 decreased the level of glucose but did not affect the levels of TAG and glycogen. These results are consistent with our previous report9. Because both Treh 18 and Treh 41 have a deletion/insertion within the intron region of the Treh gene, the hypomorphic phenotype of Treh 18 and Treh 41 is likely due to the reduced transcription and/or alterations of Treh mRNA, as reported17. Consistent with the pupal lethal phenotype, Treh 18 significantly reduced the expression of cTreh in addition to the reduction in sTreh (Fig. 2C). These results further demonstrate that Treh 18 is a hypomorphic allele of Treh. The mechanism underlying the reduced gene expression due to small changes in the intron remains unknown. The sequence around the small deletion/insertion may contain a critical enhancer region that drives the expression of Treh. An alternative possibility is that the sequence change in the intron affects splicing and thereby produces unusual transcripts.

Figure 2.

Treh 18 is a hypomorphic allele of Treh. (A) Backcrossed Treh 18 mutants exhibit pupal lethality with few escapers. The percentage of adult flies was determined by the ratio to flies with a balancer chromosome in each vial. Values shown are means and SEM. n = 6. (B) Treh 18 mutants increase trehalose levels and decrease glucose levels in late third instar larvae. Each value was normalized by protein levels and further normalized according to the level in the control larvae. (C) Treh transcript levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR at the mid third instar stage. Values are means and SD. n = 3 (B,C). *p < 0.01; (B) one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test, (C) two-tailed Student’s t-test.

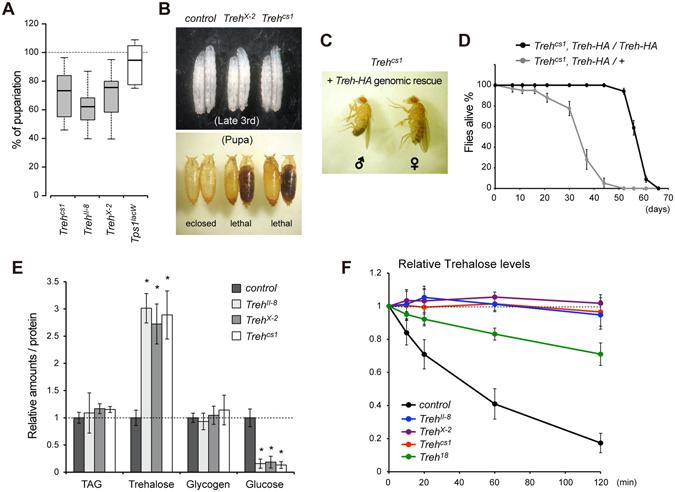

Figure 3.

Treh II-8 and Treh X-2 mutants are indistinguishable from Treh cs1 mutants. (A) The majority of Treh II-8 and Treh X-2 mutants are lethal at the pupal stage. Percentages of homozygous mutant pupae were determined by the ratio to heterozygous mutants in each vial. No statistical significances were detected by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.01). n = 6. (B) Treh X-2 and Treh cs1 mutants at late-third larval and pupal stages are shown. (C) One copy of the genomic rescue construct of Treh-HA rescues the pupal lethality of Treh cs1 homozygous mutants. (D) Survival of male flies with one copy or two copies of the genomic rescue constructs of Treh-HA in a Treh cs1 homozygous mutant background. Values shown are means and SEM. n = 4. (E) Treh II-8 and Treh X-2 mutants exhibit the identical phenotype to Treh cs1, as revealed by the increase in trehalose levels and decrease in glucose levels in late third instar larvae. Each value was normalized by protein levels and further normalized according to the levels in the control larvae. (F) Trehalase activity was measured in larval homogenates. Relative levels of trehalose are shown for each mutant. Values are means and SD. n = 4 (E,F). *p < 0.01; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test.

Treh null mutants can survive the larval stage and are lethal during the pupal phase

It has been reported that TALEN-induced null alleles of Treh, named Treh II-8, Treh IV-9, and Treh X-2, are lethal in first instar larvae in homozygosity and in trans to a chromosomal deficiency10. The authors further show that the homozygous mutant lethality can be rescued only when two copies of a genomic rescue construct exist, probably because of the lack of sequences that induce high levels of expression10. These results contradict our previous report showing that Treh cs1 mutants are lethal at the pupal stage in homozygosity and in trans to a chromosomal deficiency9. To clarify the discrepancy of the lethal stages in Treh null mutants, lethal stages of the available Treh mutants were compared under identical food conditions. We found that all Treh mutant alleles survived the larval stage and died during the pupal stage under our experimental conditions (Fig. 3A,B). However, the number of homozygous mutant pupae compared to heterozygous mutants showed variation between vials, suggesting that there is some larval lethality before the pupal stage. In addition, one copy of the genomic rescue construct was sufficient to fully rescue the pupal lethality of Treh cs1 mutants (Fig. 3C). These adult flies appeared to be unhealthy with short lifespans compared to those with two copies of the rescue constructs (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that one copy of the construct is sufficient to rescue larval and pupal lethality, but it is not enough to rescue adult lifespan under our experimental conditions. Consistent with this finding, it has been reported that glia-specific knockdown of Treh in adults leads to a lifespan reduction10. We further confirmed that all Treh null alleles increased trehalose levels and reduced glucose levels in a comparable manner (Fig. 3E). In addition, we failed to detect any trehalose hydrolysis activity in the homogenates of these mutants at the wandering stage (Fig. 3F). On the other hand, weak trehalose hydrolysis activity was detected in the homogenates of Treh 18 mutants. These results indicate that all Treh null alleles are indistinguishable from each other.

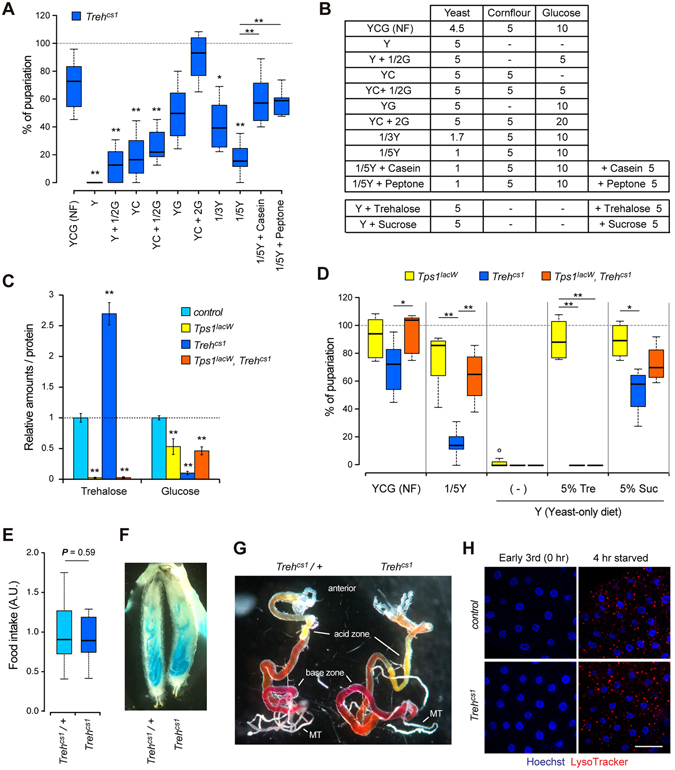

Survival and growth of Treh mutants are highly dependent on dietary conditions

The above results raise the possibility that the difference in the lethality of Treh null mutants in published studies is caused by the difference in dietary conditions. To support this idea, it has been reported that dietary conditions affect the lethality of mutants involved in energy metabolism22–25. Indeed, Tps1 mutants lacking trehalose are highly sensitive to dietary conditions in terms of their survival and body growth8. Therefore, we next analyzed the survival rate of Treh cs1 mutants under several dietary sugar conditions. Consistent with the results for the Tps1 mutants, Treh cs1 mutants all died during the larval period under low dietary sugar conditions (Fig. 4A,B). It should be noted that wild-type flies and heterozygous mutants are fully viable under these conditions. We found a clear correlation between the survival rate of Treh cs1 mutant larvae and the amounts of dietary sugar in food. A high-sugar diet, such as 20% glucose, is known to impair larval growth and cause insulin-resistant phenotypes26, 27. Such high-sugar diets further improve the survival rate of Treh cs1 mutant larvae compared with those under normal food conditions. Of note, none of the food conditions overcame the pupal lethality of Treh cs1 mutants. The lethality in Treh mutants was more severe than that of Tps1 mutants under identical food conditions, as previously reported8, indicating that Treh mutants require a higher dose of dietary sugar than Tps1 mutants for their survival.

Figure 4.

Impact of dietary conditions on the survival of Treh mutant larvae. (A) Treh mutants are sensitive to low-glucose and low-protein dietary conditions. Percentages of homozygous mutant pupae were determined by the ratio to heterozygous mutants in each vial. (B) Food compositions used in (A and D). Values are g per 100 ml. (C) The amounts of trehalose and glucose were analyzed in early-third instar larvae. Each value was normalized by protein levels and further normalized according to the level in the control larvae. Values shown are means and SD. (D) The pupariation rate of Tps1 and Treh single mutants and Tps1, Treh double mutants under various dietary conditions. Overaccumulation of trehalose rather than the loss of Treh causes deleterious effects on the adaptation to poor food conditions. Tre, trehalose; Suc, sucrose. (E) Treh mutants exhibit normal feeding behaviour. Food intake levels are evaluated by the rate of blue food ingestion at early third-instar larvae. (F) Treh mutants retain the epithelial integrity in the midgut. Leakage of ingested blue food into body cavity was tested. (G) Treh mutants have the normal segmented intraluminal pH zones in the midgut. Mid third instar larvae were fed with food containing phenol red dye to detect luminal pH. Phenol red changes from red to yellow at pH < 3 (acid zone) and to dark pink at pH > 10 (base zone). MT, Malpighian tubules. (H) Treh mutants exhibit no abnormality of autophagy in the fat body under fed and starved conditions. Dissected fat body at early third instar larvae were stained for LysoTracker (red) and Hoechst (blue) to label nuclei. Scale bar = 50 μm. n = 6~12 (A,D), n = 4 (C), or n = 10 (E). **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05; (A,C,D) one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, (E) two-tailed Student’s t-test.

In addition to dietary sugar, we found that reducing the yeast content in food significantly lowered the survival rate of Treh mutants (Fig. 4A,B). Dry yeast in fly food has been recognized as a major source of protein and amino acids, although it contains many other metabolites. To examine whether the larval lethality of Treh mutants is due to the lack of dietary protein or other metabolites, we tested the effect of protein supplementation. For this, we used casein and peptone, a mixture of polypeptides and amino acids formed by the partial hydrolysis of animal protein. In both cases, the supplementation of a protein source substantially rescued the survival rate of Treh mutants (Fig. 4A). Taken together, these results suggest that dietary conditions significantly affect the survival rate of Treh mutants.

Overaccumulation of trehalose rather than the loss of Treh causes deleterious effects on the adaptation to poor food conditions

Our observations demonstrate that Treh mutants are more sensitive to dietary conditions than Tps1 mutants that lack trehalose. The majority of Treh mutants are lethal during the larval stage under chronic low-protein diet conditions. This phenotype is specific to Treh mutants, because Tps1 mutant larvae survive to the pupal stage at a rate almost comparable to wild-type under these conditions8. Because Treh mutants retain high levels of trehalose in circulation, we hypothesized that the accumulation of trehalose rather than the loss of Treh results in lowering the adaption to poor food conditions. To address this possibility, we next generated double mutants for Tps1 and Treh to cancel out the accumulation of trehalose. As expected, the increase of trehalose in Treh mutants was completely canceled in Tps1, Treh double mutants (Fig. 4C). In addition, the significant reduction of glucose in Treh mutants was also recovered to some extent in the double mutants. We found that Tps1, Treh double mutants were lethal at the pupal stage under normal food conditions (Fig. 4D). The lethal effect of Treh mutants under low dietary protein conditions was largely suppressed by the additional loss of Tps1. These results suggest that the reduction in adaptation ability to low dietary protein in Treh mutants is mainly caused by the overaccumulation of trehalose rather than the loss of Treh.

We further asked whether the oral administration of trehalose affects the viability of Tps1 and Treh mutants. We found that the addition of trehalose to a yeast-only diet fully rescued the survival and growth of Tps1 mutant larvae (Fig. 4B,D). However, dietary trehalose failed to rescue the survival of Treh mutants and Tps1, Treh double mutants. Because sTreh is highly expressed in the midgut8, these results indicate that the utilization of trehalose as dietary sugar requires the function of Treh. On the other hand, the addition of sucrose rescued the survival of all these mutants until the pupal stage. It should be noted that the addition of trehalose or sucrose to the diet is not sufficient to rescue the internal trehalose levels and pupal lethality in Tps1 mutants (data not shown)8.

Treh mutants retain higher levels of circulating trehalose, whereas the mutants retain a very low level of free glucose. In addition, Treh mutants increase the haemolymph water volume at the expense of the reduction of intracellular fluid9. Many animals, including insects, have evolved an osmoregulation system under strict homeostatic control and thereby regulate food and water consumption based on internal nutrient abundance28–30. Consistently, Treh is highly expressed in the midgut and the Malpighian (renal) tubules during the larval period8. It is possible that Treh mutants impair feeding behaviour and/or reduce the food absorption rate, resulting in the lethal effect observed under poor food conditions. Indeed, the knockdown of trehalase in potato beetle Leptinotarsa larvae has been reported to reduce food consumption31. However, we found that Treh mutant larvae showed a normal feeding rate compared with control larvae at the early third instar (Fig. 4E). The intestinal integrity of midgut was intact in Treh mutants (Fig. 4F). The larval midgut is divided into several functional segments: an anterior neutral zone, a short acid-secreting middle segment, and a long posterior segment that secretes base into the lumen32, 33. Treh mutants did not display abnormalities in the transport of acids and bases across cell membranes as judged by a pH indicator dye, phenol red (Fig. 4G). These results imply that low adaptation to poor food conditions is unlikely due to the decrease in appetite and the defect in the midgut.

It has been reported that trehalose acts as an inhibitor of the glucose transporter and induces autophagy by depleting cellular energy34–37. The reported IC50 of the inhibitory effects by trehalose in the mammalian cell culture system is close to the in vivo concentration of trehalose in Treh mutants38. To examine whether the depletion of cellular energy resulted in the induction of autophagy occurs in Treh mutants, we next analyzed autophagosome formation in Treh mutants. Lysotracker staining revealed that autophagy was not observed in the Treh mutant fat body under fed conditions (Fig. 4H). As expected, autophagy was induced shortly after starvation in both control and Treh mutants. Similar results are essentially observed in Tps1 mutants8. Taken together, these results demonstrate that Treh mutants do not suffer from a reduction in cellular energy and that overaccumulation of trehalose itself causes deleterious effects on the maintenance of homeostasis under poor dietary conditions.

Discussion

In this study, we have reported the characterization of several mutant alleles of Treh under identical rearing conditions. Our observations reveal that the survival rate of Treh mutants is significantly influenced by dietary sugar content. Both Tps1 mutants and Treh mutants significantly reduce free glucose levels, suggesting that trehalose in circulation is continuously turned over to maintain available glucose levels. It has been reported that the amount of trehalose is rather stable compared to that of glucose shortly after food intake11. In this sense, the production of trehalose from dietary sugar in the fat body appears to be critical for buffering the fluctuation of sugar levels in the body on a long-term basis. The requirement of dietary sugar in both Treh and Tps1 mutants suggests that trehalose metabolism as the main haemolymph sugar plays a pivotal role in systemic energy homeostasis.

We show that the reduction in adaptability to low protein content in Treh mutants is caused by the overaccumulation of trehalose rather than the loss of Treh. It has been reported that trehalose acts as an inhibitor of the glucose transporter and induces autophagy by depleting cellular energy in mammals34–37. This may explain the requirement for a higher dose of dietary sugar and the reduction in adaptability to low protein content in Treh mutants. However, to the contrary, trehalose has been reported to inhibit the formation of autophagic vesicles in the Drosophila larval fat body by promoting the TOR pathway in ex vivo culture conditions38. We have shown that neither high nor a lack of trehalose caused by Treh or Tps1 mutants affect autophagy in the larval fat body in vivo 8. It remains unknown whether trehalose blocks glucose uptake by competing through the glucose transporter in Drosophila, because the in vivo concentration of circulating trehalose is relatively high. Besides the glucose transport, locomotion behavior in Treh mutant larvae looked normal (data not shown), suggesting that body wall muscles function well. We did not observe morphological defects in the Malpighian tubules in Treh mutants (data not shown). However, it is possible that Treh mutants have a functional deficit in the Malpighian tubules and that may relate to the observed lethality.

Trehalose is synthesized by two-step reactions. We previously reported that both the TPS and the TPP domains in Tps1 are required for the de novo synthesis of trehalose in Drosophila 9. In addition to the increase in trehalose, Tre6P, the precursor of trehalose in the biosynthetic pathway, may be altered in Treh mutants. The increase in Tre6P can be canceled in Tps1, Treh double mutants, because Tps1 catalyzes the production of Tre6P. Tre6P has been shown to control energy metabolism as a signaling molecule in yeast and plants39–42. In plants, Tre6P acts through the inhibition of the serine-threonine protein kinase SnRK1, a plant homologue of animal AMPK. The evolutionarily conserved SnRK1/AMPK is a sensor of energy availability and is activated under conditions of energy depletion and metabolic stress to inhibit growth for cell survival. Tre6P levels are relatively low under normal conditions. Therefore, the alteration in Tre6P levels, in addition to the increase in trehalose caused by deletion of Treh, may cause metabolic defects in the fat body. Further analysis will be required to elucidate the cause of lethality in Treh mutants under poor diet conditions.

Metabolic parameters are affected not only by genotypes but also by food conditions43, 44. Nutritional quality of commercially available dry yeast varies between manufacturers and between batches. A chemically defined standard food would be ideal to compare the mutant phenotype in different laboratories. Chemically defined food or holidic medium sustains whole development in Drosophila 45, 46. However, the growth rate of larvae is significantly lower than those reared on standard fly food containing yeast. Food composition affects metabolic homeostasis and thereby potentially influences the survival and growth rate. In particular, nutritional quality has a significant impact on mutant flies defective for enzymes involved in metabolic pathways and for endocrine hormones that regulate energy metabolism22–25. In contrast to Tps1 and Treh mutants, sugar-dependent lethality has been reported in larvae lacking the conserved carbohydrate response element-binding protein (ChREBP) Mondo-Mlx glucose-sensing transcription factors47. TGF-β/Activin-like ligand Daw mutants also exhibit high-sugar dependent larval lethality48. These factors control sugar homeostasis through the regulation of gene expression involved in glycolysis, the TCA cycle, lipogenesis, and β-oxidation47–49. Elucidating the precise regulation mechanisms of trehalose metabolism will facilitate our understanding of the adaptation of animals to various environmental conditions.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila strains

The following stocks were used: w 1118 (used as a control), Treh 18, Treh 41 (from X. Chen and H. Luo), Treh II-8, Treh X-2, Treh-HA genomic rescue construct (from S. Schirmeier), and lgl 1 and lgl 4 (from F. Matsuzaki). Tps1 lacW and Treh cs have been described previously8, 9. Treh EY06982 and Df(2R)Exel6072 (a deficiency for the Treh locus) were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. Treh 18 was back-crossed two times with the w 1118 strain and used for experiments shown in Figs 2 and 3.

Fly food

Drosophila melanogaster flies were reared on standard agar-cornmeal media at 25 °C unless otherwise indicated8, 50. The detailed food compositions, except preservatives, are shown in Fig. 4B. Casein, peptone, and trehalose were obtained from Wako Chemical, BD Biosciences, and Hayashibara, Co., respectively. All experiments were conducted under non-crowded conditions. No yeast paste was added to the fly tubes for any of the experiments. The percentage of puparium formation and adult flies was determined by counting homozygotes and heterozygotes in the same vials as an internal control.

Immunohistochemistry

Larval tissues were dissected in PBS and fixed for 10 min in 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and processed as previously described51, 52. The following primary antibodies were used: guinea pig anti-Deadpan (from J. A. Knoblich), mouse anti-Discs large, and rat anti-DEcad2 (from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). Alexa-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were used. The nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen). Images were acquired with a Zeiss LSM700 confocal microscope and were processed in Photoshop (Adobe Systems). Staining of acidic organelles was done as described previously8.

qRT-PCR analysis

qRT-PCR analyses were performed as described previously50, 51. The primers used to detect Treh (common), sTreh, cTreh, and rp49 levels were described previously8, 9.

Measurement of protein, TAG, and sugar levels

The measurement of protein, TAG, trehalose, glycogen, and glucose was performed as described previously8.

Trehalase activity assay

Trehalase activity assay was performed as described previously9. Two late third instar larvae were rinsed in PBS and homogenized on ice in 100 μl of 10 mM ammonium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) containing 0.1% TritonX-100, 2.5 mM EDTA, and Complete protease inhibitor (Roche). Five μl of the homogenates was mixed on ice with 10 μl of substrate solution (200 ng/μl trehalose and 20 ng/μl mannitol-1-13C (SIGMA) as an internal control in 10 mM ammonium acetate, pH 5.0). The reactions were started at 30 °C and stopped after the appropriate times by placing the tubes at 90 °C for 5 min. After cooling to room temperature, the assay reactions were mixed with 85 μl of acetonitrile and cleared by centrifugation, and 20 μl of the supernatant was diluted with 20 μl H2O. The amounts of trehalose were quantified by LC-MS/MS.

Quantification of trehalose and glucose by LC-MS/MS

Chromatographic separation was performed on an ACQUITY BEH Amide column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm particles, Waters) in combination with a VanGuard precolumn (5 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm particles) using an Acquity UPLC H-Class System (Waters). Elution was performed at 30 °C under isocratic conditions (0.3 ml/min, 70% acetonitrile and 30% 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 10.0). The mass spectrometric analysis was performed using a Xevo TQD triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters) coupled with an electro-spray ionization source in negative ion mode. The MRM transitions of m/z 341.2 -> 119 and m/z 182.1 -> 88.9 were used to quantify trehalose and mannitol-13C, respectively. Analytical conditions were optimized using standard solution. Sample concentrations were calculated from the standard curve obtained from serial dilution of each standard. The amounts of trehalose were normalized to the levels of mannitol-1-13C and further normalized to the levels at time 0 to determine the relative hydrolysis rate in each mutant. For the quantification of glucose, the MRM transition of m/z 179.1 -> 89.0 was used to detect glucose under conditions identical to those described above.

Food intake assay

Food intake assay was done as described previously8. Early third instar larvae were starved for 2 hours on adverse food conditions (0.8% agar in PBS) and then transferred to fresh dye food (0.5% Brilliant Blue FCF) for 20 min. After feeding, the larvae were washed in PBS, dried on tissue paper, and homogenized in 100 μl lysis buffer (6 M guanidine-HCl solution containing 0.1% Triton X-100). After boiling and centrifugation, 2 μl of supernatant was analyzed in a spectrophotometer at 630 nm. For the assessment of midgut pH, mid third instar larvae were fed with food containing 0.2% Phenol Red. After 3 hours, larvae were dissected in PBS and the midgut was photographed under a stereomicroscope (Zeiss) equipped with a digital camera (Canon). For the assessment of midgut integrity, larvae were fed with food containing 0.2% Brilliant Blue FCF for 3 hours. Larvae were observed as above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test or with Tukey’s post hoc test using GraphPad Prism 6 software. Box plots were drawn online using the BoxPlotR application (http://boxplot.tyerslab.com/). Centerlines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, and outliers are represented by dots.

Acknowledgements

We thank X. Chen, H. Luo, J. A. Knoblich, F. Matsuzaki, the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for fly stocks and antibodies; H. Kubo for technical help; and members of Fly labs in RIKEN CDB for their valuable support and discussion. We are grateful to S. Schirmeier for sharing fly materials and personal communications. This work was supported in part by Scientific Research Grants from MEXT (to T.N.).

Author Contributions

T.Y. and T.N. designed the experiments, T.Y., Y.T., and T.N. performed the experiments and analyzed the data, and T.Y. and T.N. wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wyatt GR, Kalf GF. The chemistry of insect hemolymph: trehalose and other carbohydrate. J Gen Physiol. 1957;40:833–846. doi: 10.1085/jgp.40.6.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker A, Schlöder P, Steele JE, Wegener G. The regulation of trehalose metabolism in insects. Experientia. 1996;52:433–439. doi: 10.1007/BF01919312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elbein AD, Pan YT, Pastuszak I, Carroll D. New insights on trehalose: a multifunctional molecule. Glycobiology. 2003;13:17R–27R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shukla E, Thorat LJ, Nath BB, Gaikwad SM. Insect trehalase: physiological significance and potential applications. Glycobiology. 2015;25:357–67. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwu125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crowe JH, Carpenter JF, Crowe LM. The role of vitrification in anhydrobiosis. Annu Rev Physiol. 1998;60:73–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornette R, Kikawada T. The induction of anhydrobiosis in the sleeping chironomid, current status of our knowledge. IUBMB Life. 2011;63:419–29. doi: 10.1002/iub.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tapia H, Koshland DE. Trehalose is a versatile and long-lived chaperone for desiccation tolerance. Curr Biol. 2014;24:2758–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuda H, Yamada T, Yoshida M, Nishimura T. Flies without trehalose. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:1244–1255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.619411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshida M, Matsuda H, Kubo H, Nishimura T. Molecular characterization of Tps1 and Treh genes in Drosophila and their role in body water homeostasis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30582. doi: 10.1038/srep30582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Volkenhoff A, et al. Glial glycolysis is essential for neuronal survival in Drosophila. Cell Metab. 2015;22:437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ugrankar R, et al. Drosophila glucome screening identifies Ck1alpha as a regulator of mammalian glucose metabolism. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7102. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geminard C, et al. Control of metabolism and growth through insulin-like peptides in Drosophila. Diabetes. 2006;55:S5–S8. doi: 10.2337/db06-S001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hietakangas V, Cohen SM. Regulation of tissue growth through nutrient sensing. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:389–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teleman AA. Molecular mechanisms of metabolic regulation by insulin in Drosophila. Biochem J. 2010;425:13–26. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rulifson EJ, Kim SK, Nusse R. Ablation of insulin-producing neurons in flies: growth and diabetic phenotypes. Science. 2002;296:1118–1120. doi: 10.1126/science.1070058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gáliková M, et al. Energy homeostasis control in Drosophila adipokinetic hormone mutants. Genetics. 2015;201:665–683. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.178897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X, Quan Y, Wang H, Luo H. Trehalase regulates neuroepithelial stem cell maintenance and differentiation in the Drosophila optic lobe. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nassif C, Noveen A, Hartenstein V. Early development of the Drosophila brain: III. The pattern of neuropile founder tracts during the larval period. J Comp Neurol. 2003;455:417–434. doi: 10.1002/cne.10482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yasugi T, Nishimura T. Temporal regulation of the generation of neuronal diversity in Drosophila. Dev Growth Differ. 2016;58:73–87. doi: 10.1111/dgd.12245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Apitz H, Salecker I. A region-specific neurogenesis mode requires migratory progenitors in the Drosophila visual system. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:46–55. doi: 10.1038/nn.3896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roegiers F, et al. Frequent unanticipated alleles of lethal giant larvae in Drosophila second chromosome stocks. Genetics. 2009;182:407–410. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.101808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamoto N, et al. A secreted decoy of InR antagonizes insulin/IGF signaling to restrict body growth in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2013;27:87–97. doi: 10.1101/gad.204479.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kemppainen E, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction plus high-sugar diet provokes a metabolic crisis that inhibits growth. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0145836. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Musselman LP, Fink JL, Baranski TJ. CoA protects against the deleterious effects of caloric overload in. Drosophila. J Lipid Res. 2016;57:380–387. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M062976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barry WE, Thummel CS. The Drosophila HNF4 nuclear receptor promotes glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and mitochondrial function in adults. Elife. 2016;5:e11183. doi: 10.7554/eLife.11183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musselman LP, et al. A high-sugar diet produces obesity and insulin resistance in wild-type Drosophila. Dis Model Mech. 2011;4:842–849. doi: 10.1242/dmm.007948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pasco MY, Léopold P. High sugar-induced insulin resistance in Drosophila relies on the lipocalin Neural Lazarillo. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bourque CW. Central mechanisms of osmosensation and systemic osmoregulation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:519–531. doi: 10.1038/nrn2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pool AH, Scott K. Feeding regulation in Drosophila. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2014;29:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jourjine N, Mullaney BC, Mann K, Scott K. Coupled sensing of hunger and thirst signals balances sugar and water consumption. Cell. 2016;166:855–866. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi JF, et al. Physiological roles of trehalose in Leptinotarsa larvae revealed by RNA interference of trehalose-6-phosphate synthase and trehalase genes. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;77:52–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shanbhag S, Tripathi S. Epithelial ultrastructure and cellular mechanisms of acid and base transport in the Drosophila midgut. J Exp Biol. 2009;212:1731–1744. doi: 10.1242/jeb.029306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lemaitre B, Miguel-Aliaga I. The digestive tract of Drosophila melanogaster. Annu Rev Genet. 2013;47:377–404. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-111212-133343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarkar S, Davies JE, Huang Z, Tunnacliffe A, Rubinsztein DC. Trehalose, a novel mTOR-independent autophagy enhancer, accelerates the clearance of mutant huntingtin and alpha-synuclein. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5641–5652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609532200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aguib Y, et al. Autophagy induction by trehalose counteracts cellular prion infection. Autophagy. 2009;5:361–369. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.3.7662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castillo K, et al. Trehalose delays the progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by enhancing autophagy in motoneurons. Autophagy. 2013;9:1308–1320. doi: 10.4161/auto.25188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeBosch BJ, et al. Trehalose inhibits solute carrier 2A (SLC2A) proteins to induce autophagy and prevent hepatic steatosis. Sci Signal. 2016;9:ra21. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aac5472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim J, Neufeld TP. Dietary sugar promotes systemic TOR activation in Drosophila through AKH-dependent selective secretion of Dilp3. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6846. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonçalves P, Planta RJ. Starting up yeast glycolysis. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:314–319. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(98)01305-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paul MJ, Primavesi LF, Jhurreea D, Zhang Y. Trehalose metabolism and signaling. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:417–441. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schluepmann H, Berke L, Sanchez-Perez GF. Metabolism control over growth, a case for trehalose-6-phosphate in plants. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:3379–3390. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsai AY, Gazzarrini S. Trehalose-6-phosphate and SnRK1 kinases in plant development and signaling, the emerging picture. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:119. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skorupa DA, Dervisefendic A, Zwiener J, Pletcher SD. Dietary composition specifies consumption, obesity, and lifespan in Drosophila melanogaster. Aging Cell. 2008;7:478–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tennessen JM, Barry WE, Cox J, Thummel CS. Methods for studying metabolism in Drosophila. Methods. 2014;68:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee WC, Micchelli CA. Development and characterization of a chemically defined food for Drosophila. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piper MD, et al. A holidic medium for Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Methods. 2014;11:100–105. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Havula E, et al. Mondo/ChREBP-Mlx-regulated transcriptional network is essential for dietary sugar tolerance in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghosh AC, O’Connor MB. Systemic Activin signaling independently regulates sugar homeostasis, cellular metabolism, and pH balance in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:5729–5734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319116111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mattila J, et al. Mondo-Mlx mediates organismal sugar sensing through the Gli-similar transcription factor Sugarbabe. Cell Rep. 2015;13:350–64. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Okamoto N, Nishimura T. Signaling from glia and cholinergic neurons controls nutrient-dependent production of an insulin-like peptide for Drosophila body growth. Dev Cell. 2015;35:295–310. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Okamoto N, Nishimori Y, Nishimura T. Conserved role for the Dachshund protein with Drosophila Pax6 homolog Eyeless in insulin expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2406–2411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116050109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wirtz-Peitz F, Nishimura T, Knoblich JA. Linking cell cycle to asymmetric division: Aurora-A phosphorylates the Par complex to regulate Numb localization. Cell. 2008;135:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]