Abstract

Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas (PSCs) are defined as a group of poorly differentiated non-small cell lung cancers that demonstrate sarcoma-like differentiation. The mechanism of mesenchymal differentiation in PSC is epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). The expression of homeobox protein NANOG (NANOG), which regulates the pluripotency of embryonic stem cells, is associated with the EMT process. Therefore, the present study aimed to assess the expression level of NANOG and the status of the EMT process in PSC. The data of patients with PSC were retrospectively reviewed and immunohistochemical analyses were performed on patient samples to examine the expression of NANOG and EMT-associated proteins. The comparator group included randomly selected patients with matched clinicopathological characteristics who had pulmonary adenocarcinoma (PA). In the present study, 12 patients with PSC (4 females and 8 males) were enrolled; their median age was 65 years (range, 36–79 years), and the number of patients with stage IB, IIB, IIIA, IIIB and IV disease were 1, 1, 1, 1 and 8, respectively. The immunoreactive score (IRS) for E-cadherin was significantly lower in the PSC group compared with the PA group (P<0.0001), whereas the IRS for vimentin was significantly higher in the PSC group compared with the PA group (P<0.0001). However, the IRS for NANOG was significantly decreased in the PSC group compared with the PA group (P<0.0001), which suggests that NANOG does not serve an essential role in EMT in PSC. In addition, the overall survival of patients with PSC was significantly lower compared with that of patients with PA (median survival time, 7.0 vs. 35.6 months, respectively; P=0.0256). However, no significant difference was observed in the OS of patients who expressed low compared with high levels of NANOG (P=0.4416). In conclusion, it was clearly demonstrated that cytoplasmic NANOG expression was significantly lower in PSC compared with PA, and that the EMT process in PSC was accelerated, compared with that in PA.

Keywords: PSC, homeobox protein NANOG, zinc finger protein SNAIL, EMT, vimentin, E-cadherin, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase

Introduction

Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma (PSC) is a unique disease that is defined as a group of poorly differentiated non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLCs) that demonstrate sarcoma-like differentiation (1,2). At present, five histological subgroups of PSC are defined: Pleomorphic carcinoma, spindle cell carcinoma, giant cell carcinoma, carcinosarcoma and pulmonary blastoma. Molecular biological analyses have suggested that the epithelial and mesenchymal components in PSC arise from an identical epithelial parental tumour cell (3–5). Additionally, the mechanism underlying mesenchymal differentiation in PSC is widely accepted to be epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (6–8). However, the association between the pathophysiology of PSC and the EMT process remains uncharacterised.

EMT was originally defined as a process of cellular remodelling that occurs during normal embryogenesis (9). EMT-accelerated epithelial cells lose adhesion ability, change polarity, modulate cytoskeletal constitution and switch expression from keratin-type to vimentin-type intermediate filaments (10,11). Additionally, EMT-accelerated tumour cells lose their epithelial characteristics and acquire mesenchymal characteristics, which lead to aggressive invasion and metastasis (12,13). A reduction in E-cadherin expression and an increase in vimentin expression are considered to be important hallmarks of EMT (14,15). Zinc finger protein SNAIL (Snail)-family proteins (Snail-1/Snail-2) are recognised as major transcriptional repressors of the E-cadherin gene (16,17), and in a number of malignant tumours, elevated expression of Snail-1/Snail-2 is associated with poor patient prognosis and resistance to antitumour chemotherapy (18–20).

Another key transcriptional regulator is homeobox protein NANOG (NANOG), which was originally identified as a master regulator for the maintenance of pluripotency and self-renewal capacity in embryonic stem cells (21,22). The name of this molecule is derived from ‘Tír na nÓg’: ‘Land of the young’ in Irish mythology. Previously, augmentation of NANOG expression was revealed to participate in the tumourigenesis and the self-renewal of cancer stem cells (23). Furthermore, an increase in NANOG expression has been illustrated to be associated with the EMT process in lung cancer (24,25). Consequently, the expression of the NANOG gene in PSC may be higher compared with that in pulmonary epithelial tumours, as the EMT process in PSC is enhanced compared with that in other histological subtypes of lung cancer. However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have estimated the expression level of NANOG in PSC.

In the present study, patients with PSC were retrospectively reviewed, and immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses were performed to examine the expression of NANOG and EMT-associated proteins from histological specimens obtained from the patients. The clinicopathological characteristics of the patients with PSC were compared with those of randomly selected, sex-, age-, performance status- and clinical stage-matched patients with pulmonary adenocarcinoma (PA) as the comparator group. Notably, the results revealed that NANOG expression in the patients with PSC was significantly lower compared with that in patients with PA.

Patients and methods

Data collection

The medical records of all patients in whom NSCLC had been histologically diagnosed between December 2006 and December 2010 at Kansai Medical University Takii Hospital (Moriguchi, Japan) and Hirakata Hospital (Hirakata, Japan) were retrospectively reviewed. All patients provided informed consent prior to acquisition of the histological samples. Histological diagnoses were made according to the 2004 World Health Organization/International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer histological Classification of Lung and Pleural Tumors (2). Patients were included in the present study if the diagnosis made was PSC. The clinical disease stage was assigned according to the seventh edition of the Tumor-Node-Metastasis Classification for Lung Cancer (26). Data on sex, age, smoking history, clinical stage, histological typing of cancer, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) and overall survival (OS) were obtained retrospectively from the medical records of the patients (27). Patients whose histological samples were not adequate for additional analyses were excluded. The age-, sex-, ECOG PS- and clinical stage-matched comparator group comprised of randomly selected patients for whom PA had been diagnosed at the Takii and Hirakata Hospitals of Kansai Medical University (Moriguchi, Japan) during the aforementioned period. The case-control ratio was 1:1. Patients from whom inadequate amounts of histological samples were obtained were excluded from the comparator group. The present study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Review Board of Kansai Medical University (institutional ID no. 1203; University Hospital Medical Information Network-Clinical Trials Registry no. UMIN000008737).

IHC

IHC was used to estimate the expression level of a number of EMT-associated molecules, including NANOG, in each tumour. The 7-µm-thick sections obtained from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues were deparaffinised in xylene and rehydrated in a graded series of alcohol to water. Antigen retrieval was performed using 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 121°C for 15 min. Sections were washed in Tris-buffered saline. Antigen retrieval was not performed when examining the expression of E-cadherin and vimentin. Sections were blocked with 3% H2O2 at room temperature for 10 min and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the antibodies against E-cadherin or vimentin, and at 4°C overnight for antibodies against other proteins. The primary antibodies and experimental conditions used are detailed in Table I. The sections were subsequently incubated with the ChemMate EnVision™/horseradish peroxidase kit (K5027; Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) for 45 min at room temperature according to the manufacturer's protocol. Staining was visualised by adding 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (K5007; Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) for 10 min at room temperature. Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin for 1 min and then dehydrated with a series of alcohols and xylene. Observation was then performed with light microscopy.

Table I.

Primary antibodies and conditions used for immunohistochemistry.

| Antibody | Cat. no. | Clone | Company | Species/clonality | Dilution, incubation duration and temperature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-cadherin | 999 | 42E | Cell Signalinga | Rabbit/MC | 1:200, 1 h at RT |

| Vimentin | 413541 | SP20 | Nichireib | Rabbit/MC | 1:200, 1 h at RT |

| Snail-1/Snail-2 | ab63371 | N/A | Abcamc | Rabbit/PC | 1:200, O/N at 4°C |

| p-P38 MAPK | 4631 | 12F8 | Cell Signalinga | Rabbit/MC | 1:50, O/N at 4°C |

| NANOG | 79923 | D73G4 | Cell Signalinga | Rabbit/MC | 1:800 O/N at 4°C |

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA

Nichirei Biosciences, Inc., Tokyo, Japan

Abcam, Cambridge, UK. MC, monoclonal; PC, polyclonal; RT, room temperature; O/N, overnight; p-p38 MAPK, phosphorylated p38 mitogen activated protein kinase; Snail; zinc finger protein SNAI; NANOG, homeobox protein NANOG.

Evaluation of IHC results

The results of the IHC analysis were assessed using a semi-quantitative scoring method in which the immunoreactive score (IRS) was obtained, as described previously (28). Briefly, the proportions of positively stained and intensely stained cells were determined and then staining intensity was graded as: 0, negative; 1, weak; 2, moderate or 3 strong. The percentage of positively stained cells was scored as: 0, negative; 1, ≤25%; 2, >25-≤50%; 3, >50-≤75% or 4, >75%. These two scores were multiplied to calculate the IRS, which ranged from 0–12 as follows: 0–3, low expression or 4–12, high expression. The levels of membrane staining for E-cadherin, nuclear staining for Snail-1/Snail-2 and the staining for phosphorylated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p-p38 MAPK) were estimated. To estimate the expression of vimentin and NANOG, their cytoplasmic staining was evaluated.

Statistical analysis

Non-normally distributed data are presented as the median and interquartile range. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the distribution conformity of the examined parameters featuring a normal distribution. The statistical significance of differences between groups were determined using the χ2 or Mann-Whitney U test. OS was defined as the time from initial diagnosis to the time of mortality from any cause or the last date of follow-up. Univariate analyses of OS were performed using the Kaplan-Meier estimator with the log-rank test. The 95% confidence interval (CI) for the survival rate was calculated using Greenwood's method (29). To calculate the 95% CI of the median survival time (MST), the Brookmeyer and Crowley method (30) was used. All statistical analyses were conducted using JMP software for Windows (version 9.0.2; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All statistical tests were two-tailed, and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Patient clinicopathological characteristics

Between December 2006 and December 2010, histological diagnoses were performed on 996 patients, and PSC and PA were diagnosed in 14 patients (1.4%) and 612 patients (61.4%), respectively. In the present study, 12 patients with PSC for whom adequate amounts of histological specimens were available were enrolled. The clinicopathological characteristics of these 12 patients are summarised in Table II. All patients were Asian, the median age was 65 years (range, 36–79 years), and included 4 females and 8 males. A total of 7 patients had a history of smoking, while the remaining 5 had never smoked. The numbers of patients with pleomorphic carcinoma, spindle cell carcinoma and pulmonary blastoma were 10, 1 and 1, respectively. The present study did not include patients with other histological subtypes of PSC, including giant cell carcinoma and carcinosarcoma. The ECOG PS was 0–1 in 8 patients and 2–4 in 4 patients. The numbers of patients with stage IB, IIB, IIIA, IIIB and IV disease were 1, 1, 1, 1 and 8, respectively. A total of 8 patients had received initial systemic chemotherapy, whereas 3 patients had undergone a surgical resection with curative intention. Only 1 patient had received supportive care alone.

Table II.

Patient clinicopathological characteristics.

| Clinicopathological characteristic | PSC (n=12) | PA (n=112) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 65 (36–79) | 69.5 (60–83) | 0.1559 |

| Sex (male/female) | 8/4 | 8/4 | 1.000 |

| ECOG PS (0–1/2-4) | 8/4 | 8/4 | 1.000 |

| Smoking history | 1.000 | ||

| Never | 5 | 5 | |

| Past/Current | 7 | 7 | |

| Clinical stage | 1.000 | ||

| IA-IIIA | 3 | 3 | |

| IIIB-IV | 9 | 9 | |

| Initial treatment | 0.5890 | ||

| Surgery | 3 | 3 | |

| Chemotherapy | 8 | 9 | |

| Radiotherapy | 0 | 0 | |

| Supportive care | 1 | 0 | |

| EGFR mutation | 0.0061 | ||

| Exon 19 deletion | 0/3 | 5/9 |

PSC, pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma; PA, pulmonary adenocarcinoma; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor.

To evaluate the clinicopathological characteristics of the patients with PSC, a comparator group of 12 age-, sex-, ECOG PS- and disease stage-matched patients were randomly selected from among the patients with PA. Table II summarises the data obtained for the two groups. Age, sex and smoking history did not differ significantly between the two groups. 9 of the 12 patients with PA and 3 of the 12 patients with PSC were examined for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-activating mutations. EGFR-activating mutations were detected in 5 of the 9 tested patients with PA, whereas no activating mutation was found in the 3 patients with PSC that were tested. Consequently, EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors were used to treat the 5 detected patients with PA, and none of the patients with PSC.

Comparison of the expression of EMT-associated proteins between patients with PSC and patients with PA

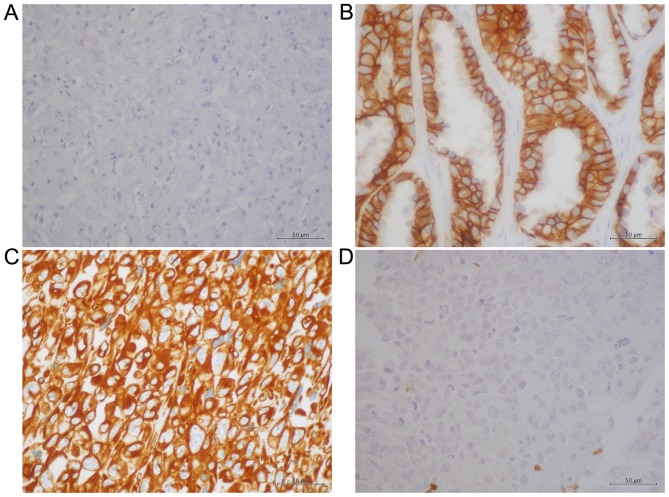

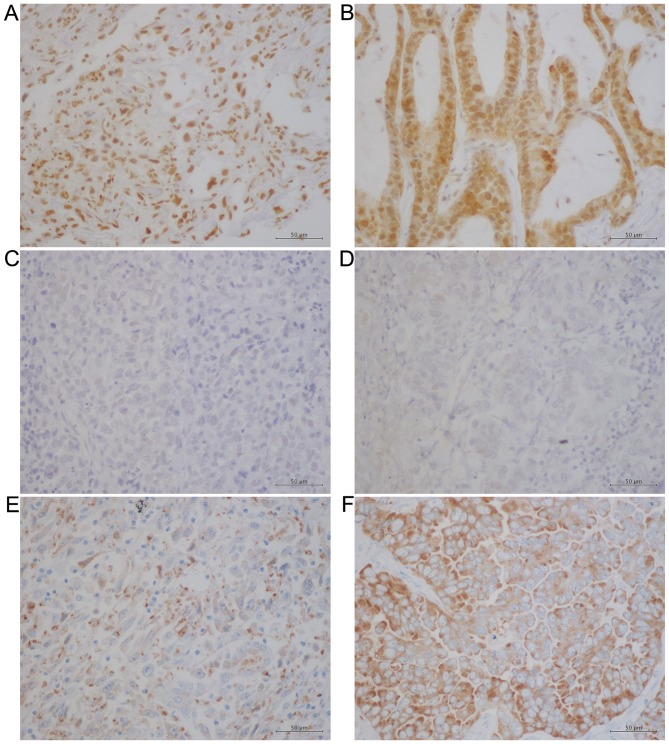

IHC analyses were performed to examine the expression of various EMT-associated proteins and NANOG in the histological specimens acquired from the patients in the two groups. Figs. 1 and 2 present representative IHC data obtained for these proteins. Whereas E-cadherin exhibited a membranous pattern of distribution (Fig. 1A and 1B), vimentin was detected in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1C and D). Conversely, Snail-1/Snail-2 (Fig. 2A and B) and p-p38 MAPK (Fig. 2C and D) were observed primarily in nucleus, which is in agreement with previous reports (31,32), whereas NANOG was detected primarily in the cytoplasm in PSC and PA samples (Fig. 2E and F). The IHC results were evaluated using a semi-quantitative method using the calculation of IRS and Table III summarises these results. The IRS of E-cadherin was significantly lower in the PSC group compared with the PA group (P<0.0001), whereas the IRS of vimentin was significantly higher in the PSC group compared with the PA group (P<0.0001). These results suggest that the EMT process is accelerated in PSC compared with PA. However, the IRS of Snail-1/Snail-2 did not differ significantly between the two groups (P=0.0715) and nor did that of p-p38 MAPK (P=0.3434). Finally, the IRS of NANOG was significantly decreased in the PSC group compared with the PA group (P<0.0001). These results indicate that NANOG does not serve an essential role in the EMT process in PSC.

Figure 1.

Representative IHC staining for E-cadherin and vimentin. IHC analysis for E-cadherin demonstrated (A) negative staining in the pleomorphic carcinoma subtype of PSC and (B) strongly positive membranous staining in PA. Conversely, IHC staining for vimentin was (C) strongly positive in the cytoplasm in the pleomorphic carcinoma subtype of PSC and (D) negative in PA. Magnification, ×400. IHC, immunohistochemical; PSC, pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma; PA, pulmonary adenocarcinoma.

Figure 2.

Representative IHC staining for Snail-1/Snail-2, p-P38 MAPK and NANOG. There was positive nuclear IHC staining for Snail-1/Snail-2 in (A) the spindle cell carcinoma subtype of PSC and (B) PA. In addition, no notable difference was observed in the nuclear staining for p-P38 MAPK between (C) the pleomorphic carcinoma subtype of PSC and (D) PA. Cytoplasmic IHC staining was detected for NANOG, which was weak in (E) the pleomorphic carcinoma subtype of PSC and (F) moderate in PA. Magnification, ×400. IHC, immunohistochemical; Snail, zinc finger protein SNAI; p-p38 MAPK, phosphorylated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase; PSC, pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma; PA, pulmonary adenocarcinoma.

Table III.

Results of immunohistochemical analysis.

| Protein | PSC (n=12) | PA (n=12) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-cadherin | 1.0 (0–3.3) | 12.0 (9.0–12.0) | <0.0001 |

| Vimentin | 12.0 (12.0–12.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | <0.0001 |

| Snail-1/Snail-2 | 6.0 (2.0–8.0) | 10.5 (6.0–12.0) | 0.0715 |

| p-p38 MAPK | 1.5 (1.0–2.0) | 2.0 (1.0–5.0) | 0.3434 |

| NANOG | 3.4 (2.7–4.7) | 11.5 (8.0–12.0) | 0.0001 |

Data are presented as the median and interquartile range. PSC, pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma; PA, pulmonary adenocarcinoma; p-p38 MAPK, phosphorylated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase; Snail; zinc finger protein SNAI; NANOG, homeobox protein NANOG.

Univariate analyses of OS

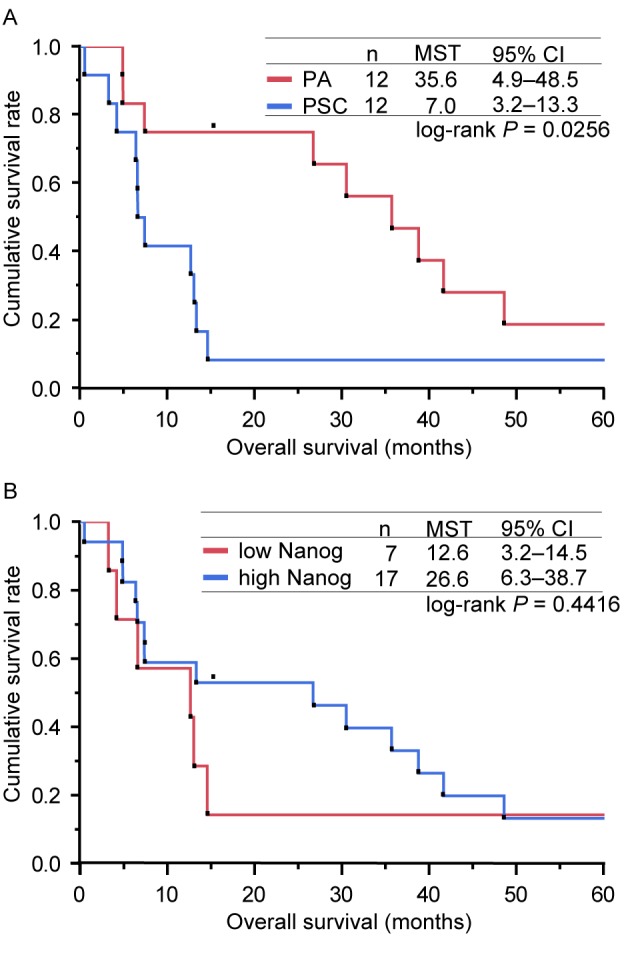

A series of survival analyses were conducted on the 24 enrolled patients on April 30th 2015, by which 21 patients had succumbed due to PSC or other causes, 2 had been lost to follow-up and 1 remained alive. Consequently, the censoring rate was estimated to be 12.5%. The MSTs were 7.0 months (95% CI, 3.2–13.3) and 35.6 months (95% CI, 4.9–48.5) for patients with PSC and PA, respectively (Fig. 3A). The 1-year survival rates were 41.7% (95% CI, 13.8–69.6) and 75.0% (95% CI, 50.5–99.5) for patients with PSC and PA, respectively (Fig. 3A). Univariate analyses revealed that OS was significantly decreased in patients with PSC (P=0.0256 vs. PA), in patients with a poor ECOG PS (P=0.0063; 0–1 vs. 2–4) and in patients with clinical stage IIIB or IV disease (P=0.0080 vs. IA-IIIA) (Table IV). However, sex (P=0.4637; male vs. female), patient age (P=0.6989; <75 vs. ≥75 years) and smoking history (P=0.1319; never vs. past/current) were not significantly associated with OS (Table IV). The contribution of the IRS of NANOG to OS was also analysed. The MSTs were 12.6 months (95% CI: 3.2–14.5) and 26.6 months (95% CI: 6.3- 38.7) for patients who expressed NANOG protein at low and high levels, respectively (Fig. 3B). Univariate analysis revealed no significant difference between the two groups (P=0.4416; Table IV). In addition, the contribution to OS of the IRS of the four other proteins examined was investigated. This identified that only a low-level expression of vimentin was a favourable factor for OS (P=0.0348 vs. high expression); the expression levels of E-cadherin (P=0.2166; low vs. high expression), Snail-1/Snail-2 (P=0.7065; low vs. high expression) and p-p38 MAPK (P=0.7400; low vs. high expression) did not demonstrate a statistically significant effect on OS (Table IV).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves for the overall survival of patients in the present study. (A) Kaplan-Meier curves for the OS of patients according to the type of lung cancer (PA or PSC). The MSTs determined for the patients with PSC and PA were 7.0 and 35.6 months, respectively (log-rank test, P=0.0256). (B) Kaplan-Meier curves for OS of patients, presented according to the expression level of NANOG (low or high). The MSTs calculated for the patients who expressed NANOG at low and high levels were 12.6 and 26.6 months, respectively (log-rank test, P=0.4416). OS, overall survival; PSC, pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma; PA, pulmonary adenocarcinoma; MSTs, median survival times; CI, confidence interval; NANOG, homeobox protein NANOG.

Table IV.

Results of univariate analysis of overall survival.

| Variable | Median survival time (months) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Histology: PSC vs. PA | 7.0 vs. 35.6 | 0.0256 |

| ECOG PS: 0–1 vs. 2–4 | 26.6 vs. 6.1 | 0.0063 |

| Sex: male vs. female | 13.1 vs. 13.6 | 0.4637 |

| Age: <75 vs. ≥75 | 13.1 vs. 21.5 | 0.6989 |

| Smoking status: never vs. past/current | 10.0 vs. 20.0 | 0.1319 |

| Clinical stage: IA-IIIA vs. IIIB-IV | 59.8 vs. 10.0 | 0.0080 |

| E-cadherin: low vs. high | 12.6 vs. 30.4 | 0.2166 |

| Vimentin: low vs. high | 38.7 vs. 7.3 | 0.0348 |

| Snail-1/Snail-2: low vs. high | 6.6 vs. 13.3 | 0.7065 |

| p-p38 MAPK: low vs. high | 13.0 vs. 13.3 | 0.7400 |

| NANOG: low vs. high | 12.6 vs. 26.6 | 0.4416 |

PSC, pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma; PA, pulmonary adenocarcinoma; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; p-p38 MAPK, phosphorylated p38 mitogen activated protein kinase; Snail, zinc finger protein SNAI; NANOG, homeobox protein NANOG.

Discussion

NANOG expression has been widely examined in tumour tissues obtained from patients with lung cancer (33,34), and the results have revealed that NANOG expression does not differ substantially between the histological subtypes of lung cancer, including adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, large cell carcinoma, bronchoalveolar carcinoma and small cell carcinoma. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing the expression of NANOG in PSC.

The correlation between NANOG expression and the EMT process has been discussed extensively. Meng et al (28) revealed that NANOG protein expression was induced in response to tumour growth factor (TGF)-β stimulation of a colorectal cancer cell line in a Snail-dependent manner. Chiou et al (23) demonstrated that the co-expression of NANOG and octamer-binding transcription factor 4 promoted EMT, indicated by a reduction in E-cadherin expression and an increase in vimentin expression, in the pulmonary adenocarcinoma A549 cell line. Additionally, Luo et al (35) demonstrated that the expression of NANOG was positively correlated with that of Snail, but negatively correlated with that of E-cadherin in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. The results of the present study indicate that the EMT process in PSC is accelerated compared with that in PA. However, the current results also revealed that NANOG expression in PSC was significantly lower compared with that in PA. In addition, no statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups in terms of the expression of Snail-1/Snail-2 and p-p38 MAPK, which are major signal transducing molecules in EMT. A previous study provides one possible explanation for the reduced expression of NANOG observed in PSC: Chen et al (36) assessed the expression of NANOG in primary tumours at the frontline between tumour and normal tissue, and in malignant pleural effusions of PA, demonstrating that a situation-dependent up-regulation of the NANOG gene occurred at the frontline of tumour progression compared with quiescent areas. According to the hypothesis of Chen et al (36), quiescent tumour cells obtained from PSC may express only small amounts of NANOG. Thus, in the present study, transient NANOG expression in PSC may not have been detected with the IHC method. However, quiescent and NANOG-negative tumour cells constitutively demonstrated mesenchymal characteristics, indicating an acceleration of the EMT process. These discrepancies suggest that NANOG does not serve an essential role in PSC EMT. Numerous signalling pathways are known to promote EMT, including the mothers against decapentaplegic homolog-dependent/independent TGF-β, phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B, Wnt/glycogen synthase kinase 3β and the extracellular signal-regulated kinase/p38 MAPK signalling pathways (37–41). One or more of these signalling pathways may be involved in the EMT process in PSC, rather than NANOG.

NANOG contains conserved homeodomain motifs, which indicates that the protein functions as a transcription factor (21). To facilitate the transcription of a target gene, a transcription factor must localise in the nucleus and bind to the promoter region of the target gene in vivo. The NANOG gene product contains a nuclear localisation signal and a nuclear export signal (42,43), suggesting that a molecular shuttling of NANOG between the intra-nuclear space and the cytoplasmic space occurs. The subcellular localisation of NANOG various types of human malignant tumours has been demonstrated, and, notably, the following three independent types of NANOG localisation have been described: In the nucleus, as illustrated in germ cell tumours (44); in the nucleus and the cytoplasm, as identified in prostate and breast cancer (44,45) and primarily in the cytoplasm, as demonstrated in colorectal and ovarian cancer (28,46). However, the subcellular localisation of NANOG in lung cancer remains debatable (23,25,33,34). The results of the present study demonstrated that NANOG was localised primarily in the cytoplasm in PSC and PA, with a small proportion of nuclear staining. Gu et al (47) suggested a possible role for cytoplasmic NANOG by demonstrating that cytoplasmic NANOG-positive tumour stromal cells promoted the proliferation and tumourigenesis of human cervical cancer cells. Cytoplasmic NANOG was previously identified to be an independent unfavourable prognostic factor for OS in patients with colorectal cancer (28). A previous study also revealed the unfavourable prognostic effects of the overexpression of cytoplasmic NANOG in patients with lung cancer (33). However, the results of the present study did not reveal a statistically significant unfavourable effect of cytoplasmic NANOG on the survival of the patients examined. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that an unfavourable survival effect of mesenchymal differentiation through EMT overcomes the effect of NANOG overexpression in lung cancer.

In conclusion, despite the small sample size used in the present study, the data clearly demonstrated that cytoplasmic NANOG expression was significantly lower in PSC compared with PA, and that the EMT process in PSC was accelerated compared with that in PA. Further investigations are warranted to clarify the biological role of NANOG in lung cancer.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for their English language editing.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- PSC

pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma

- PA

pulmonary adenocarcinoma

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- OS

overall survival

- IRS

immunoreactive score

References

- 1.Pelosi G, Sonzogni A, De Pas T, Galetta D, Veronesi G, Spaggiari L, Manzotti M, Fumagalli C, Bresaola E, Nappi O. Review article: Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas: A practical overview. Int J Surg Pathol. 2010;18:103–120. doi: 10.1177/1066896908330049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Müller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. IARC Press; Lyon: 2004. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours; pp. 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dacic S, Finkelstein SD, Sasatomi E, Swalsky PA, Yousem SA. Molecular pathogenesis of pulmonary carcinosarcoma as determined by microdissection-based allelotyping. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:510–516. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200204000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holst VA, Finkelstein S, Colby TV, Myers JL, Yousem SA. p53 and K-ras mutational genotyping in pulmonary carcinosarcoma, spindle cell carcinoma, and pulmonary blastoma: Implications for histogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:801–811. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199707000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sekine S, Shibata T, Matsuno Y, Maeshima A, Ishii G, Sakamoto M, Hirohashi S. Beta-Catenin mutations in pulmonary blastomas: Association with morule formation. J Pathol. 2003;200:214–221. doi: 10.1002/path.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blaukovitsch M, Halbwedl I, Kothmaier H, Gogg-Kammerer M, Popper HH. Sarcomatoid carcinomas of the lung-are these histogenetically heterogeneous tumors? Virchows Arch. 2006;449:455–461. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0256-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakatani Y, Miyagi Y, Takemura T, Oka T, Yokoi T, Takagi M, Yokoyama S, Kashima K, Hara K, Yamada T, et al. Aberrant nuclear/cytoplasmic localization and gene mutation of beta-catenin in classic pulmonary blastoma: Beta-catenin immunostaining is useful for distinguishing between classic pulmonary blastoma and a blastomatoid variant of carcinosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:921–927. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200407000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haraguchi S, Fukuda Y, Sugisaki Y, Yamanaka N. Pulmonary carcinosarcoma: Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies. Pathol Int. 1999;49:903–908. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.1999.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hay ED. Organization and fine structure of epithelium and mesenchyme in the developing chick embryo. In: Fleischmajer R, Billingham RE, editors. Epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore, Maryland, USA: 1968. pp. 31–55. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenburg G, Hay ED. Epithelia suspended in collagen gels can lose polarity and express characteristics of migrating mesenchymal cells. J Cell Biol. 1982;95:333–339. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.1.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miettinen PJ, Ebner R, Lopez AR, Derynck R. TGF-beta induced transdifferentiation of mammary epithelial cells to mesenchymal cells: Involvement of type I receptors. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:2021–2036. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sommers CL, Thompson EW, Torri JA, Kemler R, Gelmann EP, Byers SW. Cell adhesion molecule uvomorulin expression in human breast cancer cell lines: Relationship to morphology and invasive capacities. Cell Growth Differ. 1991;2:365–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oka H, Shiozaki H, Kobayashi K, Inoue M, Tahara H, Kobayashi T, Takatsuka Y, Matsuyoshi N, Hirano S, Takeichi M, et al. Expression of E-cadherin cell adhesion molecules in human breast cancer tissues and its relationship to metastasis. Cancer Res. 1993;53:1696–1701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burdsal CA, Damsky CH, Pedersen RA. The role of E-cadherin and integrins in mesoderm differentiation and migration at the mammalian primitive streak. Development. 1993;118:829–844. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.3.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson EW, Torri J, Sabol M, Sommers CL, Byers S, Valverius EM, Martin GR, Lippman ME, Stampfer MR, Dickson RB. Oncogene-induced basement membrane invasiveness in human mammary epithelial cells. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1994;12:181–194. doi: 10.1007/BF01753886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cano A, Pérez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, Portillo F, Nieto MA. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:76–83. doi: 10.1038/35000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolós V, Peinado H, Pérez-Moreno MA, Fraga MF, Esteller M, Cano A. The transcription factor Slug represses E-cadherin expression and induces epithelial to mesenchymal transitions: A comparison with Snail and E47 repressors. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:499–511. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blechschmidt K, Sassen S, Schmalfeldt B, Schuster T, Höfler H, Becker KF. The E-cadherin repressor Snail is associated with lower overall survival of ovarian cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:489–495. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shih JY, Tsai MF, Chang TH, Chang YL, Yuan A, Yu CJ, Lin SB, Liou GY, Lee ML, Chen JJ, et al. Transcription repressor slug promotes carcinoma invasion and predicts outcome of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8070–8078. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haslehurst AM, Koti M, Dharsee M, Nuin P, Evans K, Geraci J, Childs T, Chen J, Li J, Weberpals J, et al. EMT transcription factors snail and slug directly contribute to cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:91. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chambers I, Colby D, Robertson M, Nichols J, Lee S, Tweedie S, Smith A. Functional expression cloning of Nanog, a pluripotency sustaining factor in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2003;113:643–655. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitsui K, Tokuzawa Y, Itoh H, Segawa K, Murakami M, Takahashi K, Maruyama M, Maeda M, Yamanaka S. The homeoprotein Nanog is required for maintenance of pluripotency in mouse epiblast and ES cells. Cell. 2003;113:631–642. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiou SH, Wang ML, Chou YT, Chen CJ, Hong CF, Hsieh WJ, Chang HT, Chen YS, Lin TW, Hsu HS, Wu CW. Coexpression of Oct4 and Nanog enhances malignancy in lung adenocarcinoma by inducing cancer stem cell-like properties and epithelial-mesenchymal transdifferentiation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:10433–10444. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li XQ, Yang XL, Zhang G, Wu SP, Deng XB, Xiao SJ, Liu QZ, Yao KT, Xiao GH. Nuclear β-catenin accumulation is associated with increased expression of Nanog protein and predicts poor prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer. J Transl Med. 2013;11:114. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pirozzi G, Tirino V, Camerlingo R, Franco R, La Rocca A, Liguori E, Martucci N, Paino F, Normanno N, Rocco G. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition by TGFβ-1 induction increases stemness characteristics in primary non small cell lung cancer cell line. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, Giroux DJ, Groome PA, Rami-Porta R, Postmus PE, Rusch V, Sobin L. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer International Staging Committee; Participating Institutions: The IASLC lung cancer staging project: Proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM Classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:706–714. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812f3c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, Carbone PP. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–655. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198212000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meng HM, Zheng P, Wang XY, Liu C, Sui HM, Wu SJ, Zhou J, Ding YQ, Li J. Over-expression of Nanog predicts tumour progression and poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9:295–302. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.4.10666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenwood M, editor. Reports on Public Health and Medical Subjects. Her Majesty's Stationery Office; London: 1926. The natural duration of cancer; pp. 1–26. No. 33. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brookmeyer R, Crowley J. A confidence interval for the median survival time. Biometrics. 1982;38:29–41. doi: 10.2307/2530286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SH, Kim JM, Shin MH, Kim CW, Huang SM, Kang DW, Suh KS, Yi ES, Kim KH. Correlation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers with clinicopathologic parameters in adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Histol Histopathol. 2012;27:581–591. doi: 10.14670/HH-27.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vicent S, Garayoa M, López-Picazo JM, Lozano MD, Toledo G, Thunnissen FB, Manzano RG, Montuenga LM. Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 is overexpressed in non-small cell lung cancer and is an independent predictor of outcome in patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3639–3649. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du Y, Ma C, Wang Z, Liu Z, Liu H, Wang T. Nanog, a novel prognostic marker for lung cancer. Surg Oncol. 2013;22:224–229. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gialmanidis IP, Bravou V, Petrou I, Kourea H, Mathioudakis A, Lilis I, Papadaki H. Expression of Bmi1, FoxF1, Nanog, and γ-catenin in relation to hedgehog signaling pathway in human non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung. 2013;191:511–521. doi: 10.1007/s00408-013-9490-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo W, Li S, Peng B, Ye Y, Deng X, Yao K. Embryonic stem cells markers SOX2, OCT4 and Nanog expression and their correlations with epithelial-mesenchymal transition in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen SF, Lin YS, Jao SW, Chang YC, Liu CL, Lin YJ, Nieh S. Pulmonary adenocarcinoma in malignant pleural effusion enriches cancer stem cell properties during metastatic cascade. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piek E, Moustakas A, Kurisaki A, Heldin CH, ten Dijke P. TGF-(beta) type I receptor/ALK-5 and Smad proteins mediate epithelial to mesenchymal transdifferentiation in NMuMG breast epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:4557–4568. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.24.4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhowmick NA, Ghiassi M, Bakin A, Aakre M, Lundquist CA, Engel ME, Arteaga CL, Moses HL. Transforming growth factor-beta1 mediates epithelial to mesenchymal transdifferentiation through a RhoA-dependent mechanism. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:27–36. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bakin AV, Tomlinson AK, Bhowmick NA, Moses HL, Arteaga CL. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase function is required for transforming growth factor beta-mediated epithelial to mesenchymal transition and cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36803–36810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005912200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim K, Lu Z, Hay ED. Direct evidence for a role of beta-catenin/LEF-1 signaling pathway in induction of EMT. Cell Biol Int. 2002;26:463–476. doi: 10.1006/cbir.2002.0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhowmick NA, Zent R, Ghiassi M, McDonnell M, Moses HL. Integrin beta 1 signaling is necessary for transforming growth factor-beta activation of p38MAPK and epithelial plasticity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:46707–46713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106176200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Do HJ, Lim HY, Kim JH, Song H, Chung HM, Kim JH. An intact homeobox domain is required for complete nuclear localization of human Nanog. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353:770–775. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang DF, Tsai SC, Wang XC, Xia P, Senadheera D, Lutzko C. Molecular characterization of the human NANOG protein. Stem Cells. 2009;27:812–821. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ezeh UI, Turek PJ, Reijo RA, Clark AT. Human embryonic stem cell genes OCT4, NANOG, STELLAR, and GDF3 are expressed in both seminoma and breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:2255–2265. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miyazawa K, Tanaka T, Nakai D, Morita N, Suzuki K. Immunohistochemical expression of four different stem cell markers in prostate cancer: High expression of NANOG in conjunction with hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression is involved in prostate epithelial malignancy. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:985–992. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pan Y, Jiao J, Zhou C, Cheng Q, Hu Y, Chen H. Nanog is highly expressed in ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma and correlated with clinical stage and pathological grade. Pathobiology. 2010;77:283–288. doi: 10.1159/000320866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gu TT, Liu SY, Zheng PS. Cytoplasmic NANOG-positive stromal cells promote human cervical cancer progression. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:652–661. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]