Abstract

Incontinentia pigmenti (IP; Bloch–Sulzberger syndrome) is a rare, genetic syndrome inherited as an X-linked dominant trait. It primarily affects female infants and is lethal in the majority of males during fetal life. The clinical findings include skin lesions, developmental defects, and defects of the eyes, teeth, skeletal system, and central nervous system. Cardiovascular complications of this disease in general, and pulmonary hypertension in particular, are extremely rare. This report describes the case of a 3-year-old girl with IP complicated by pulmonary arterial hypertension. Extensive cardiology workup done to the patient indicates underlying vasculopathy. This report sheds light on the relationship between IP and pulmonary hypertension, reviews the previously reported cases, and compares them with the reported case.

Keywords: incontinentia pigmenti, IKBKG, pulmonary hypertension, vasculopathy, Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome, lines of Blaschko, hyperpigmentation

Introduction

Incontinentia pigmenti (IP; Bloch–Sulzberger syndrome; Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM# 308300]) is a rare hereditary disease inherited as an X-linked dominant trait. It primarily affects female infants and is lethal in the majority of males during fetal life.1 Approximately 1,000 cases have been reported in the literature and the female: male ratio ranges from ~20–37:1.2

IP occurs due to a genetic mutation in the IKBKG gene (inhibitor of the kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, kinase gamma; NM_003639.4), which is located on the X chromosome at position q28.3 This gene is also known as nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) essential modulator (NEMO). It encodes for regulatory NEMO/IKKγ (I-kappa B kinase), which causes phosphorylation and degradation of the inhibitor bound to NF-κB in the cytosol. The dissociated, active, NF-κB enters the nucleus and then assumes the role of a transcription factor.4,5 The NF-κB pathway plays an important role in the immune system and regulates the expression of many genes outside the immune system, including that involved in embryonic development and the development of bone, mammary glands, skin, and central nervous system (CNS).6,7

IP has a broad spectrum of clinical features reflecting the involvement of different organs of the body, including the eyes, skeletal system, skin, and CNS. Landy and Donnai initially proposed the diagnostic criteria for IP.8 They divided patients into two groups based on the family history of IP in first-degree female relatives and set the major criteria as typical skin manifestations, which are usually the first sign to appear. In addition, they subdivided the skin manifestations into four stages comprising blisters preceded by erythema, hyperkeratotic verrucous lesions, hyperpigmentation, and finally, hypopigmentation and loss of hair stage. Minor criteria comprised dental manifestations and hair, nail, and retinal involvement. In the absence of familial history, the presence of at least one major criterion is required, while the presence of minor criteria further supports a diagnosis of IP. Complete absence of minor criteria leads to an uncertain diagnosis.

In 2014, Minic et al proposed the addition of CNS, palate, breast, and nipple anomalies, multiple male miscarriages, and pathohistological manifestations to the minor criteria for the disease.9 Skin manifestation stages appear sequentially over time, but patients might harbor variable stages simultaneously.8 In more uncommon cases, cardiac malformations may present as ventricular endomyocardial fibrosis, tricuspid insufficiency, and pulmonary hypertension.10

This report describes a case of a 3-year-old girl diagnosed with IP complicated by pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Methods

Clinical evaluation

A retrospective chart review was undertaken for the patient, and all data were collected and summarized.

Analysis of gene mutation

Genomic DNA was screened by single-tier polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification for the common deletion of exons 4–10 in the IKBKG (NEMO) gene. The patient’s specimen, along with control samples, was amplified by long-range PCR amplification with primers designed to produce DNA fragments of specific sizes in the presence of the concurrent deletion. Normal control samples analyzed concurrently on an agarose gel along with the patient’s DNA were not expected to produce a visible band when amplified under the used PCR conditions. The result was confirmed in a new PCR amplicon/preparation of DNA by repeat analysis.11

Case report

This report describes a 3-year-old girl who was a product of nonconsanguineous marriage, and who was born at full term by cesarean section owing to non-reassuring cardiotocography. The family history was negative for a similar condition, recurrent miscarriages, or neonatal deaths.

A few hours after birth, the newborn was taken to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) because of respiratory distress which necessitated intubation and mechanical ventilation.

Investigations including cardiac echo showed persistent pulmonary hypertension (PHTN) of the newborn. Throughout her stay in the NICU, she developed skin rash with vesicles and pustules, which were initially suspected to be herpes simplex or impetigo, but over time, the lesions became hyperpigmented.

At 30 days of age, her condition improved; so she was extubated and discharged home without a definitive diagnosis. Her pulmonary hypertension persisted, and she started to develop episodes of cyanotic spells and exhibited decreased level of consciousness mainly with crying.

At 18 months of age, she had a viral illness, after which the cyanotic spells became more frequent. The patient was admitted and an echocardiogram was performed revealing persistent pulmonary hypertension; so she was started on diuretics (furosemide). Later, at the age of 2 years, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor (sildenafil) was added to the existing regimen. Thereafter, the patient was referred to the tertiary center at King Abdulaziz Medical City – because of complicated pulmonary hypertension – for further investigations and management.

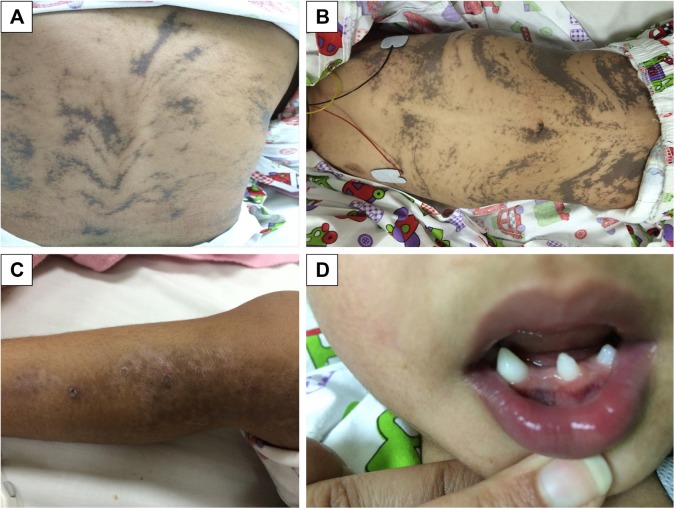

On examination, she was found to have hyperpigmented skin over her chest, abdomen, and back which followed the lines of Blaschko (Figure 1). Hyperpigmented lesions were also found over her scalp. She had hypopigmentation over her lower limbs with atrophic scar (Figure 1) and had missing teeth, conoid teeth (Figure 1), and wooly hair. There were no noticeable changes in her nails. Her neurological examination was unremarkable; she had normal power, tone, and reflexes.

Figure 1.

Patient’s skin and teeth manifestations.

Notes: (A, B) Hyperpigmented lesions on the back and abdomen; (C) stage 4 hypopigmented lesion on the lower limbs; (D) conoid and missing teeth.

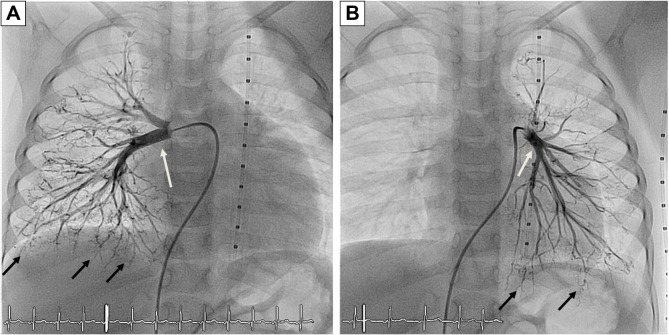

Laboratory investigations were normal with no eosinophilia. Her echocardiogram showed severe pulmonary, supra-systemic, hypertension; severe tricuspid regurgitation with peak gradient at 135 mmHg; D-shaped compressed left ventricle; severely dilated hypertrophied right ventricle; and atrial septal defect (5 mm) with mainly right-to-left shunt. The computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the chest showed that her pulmonary arteries were not dilated, which raised the concern of native pulmonary artery hypoplasia. Accordingly, cardiac catheterization was performed and showed distal bilateral pulmonary artery stenosis (type 5); left pulmonary artery, 7.9 mm; right pulmonary artery, 7.8 mm; and Nakata index, 203 (330±30 mm2/m2).12 The cardiac catheterization revealed collaterals from plural arteries and complete obstruction of some arterioles bilaterally (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cardiac catheterization.

Notes: (A) Right pulmonary artery; (B) left pulmonary artery. Black arrows point to collateral vessels; white arrows point to right and left pulmonary arteries.

Based on clinical findings, IP was suspected. Definitive diagnosis was reached by molecular investigation, as described in the “Analysis of gene mutation” section, which showed deletion of exons 4–10 on the IKBKG gene.

Now, she is a 3-year-old girl, and her developmental milestones are appropriate for her age. All her growth parameters are below the fifth percentile (height 88.7 cm, weight 11 kg, head circumference 44 cm). Her cardiovascular condition is stable on furosemide 6 mg once daily and sildenafil 9 mg once daily.

Discussion

IP is a rare inherited neurocutaneous disorder, distinguished by classical skin lesions with frequent multisystem involvement.

It primarily affects females, as in this case, because in affected hemizygous male fetuses the pregnancy will terminate with spontaneous abortion owing to extensive apoptosis in fetal cells, although IP was reported previously in XXY male patients and males with somatic mosaicism.1,13,14

In 80% of cases, there is a deletion of exons 4–10 on the IKBKG gene,1,15,16 which was established in the present case by molecular testing. Most cases develop skin lesions on the trunk, extremities, and scalp, which were spotted in the patient observed in this study. Characteristic skin lesions evolve through the following four known stages.17

Stage 1, known as the inflammatory or vesicular stage, is recognized by the development of papules, vesicles, and pustules on an erythematous base, spread linearly along the lines of Blaschko. In most patients (>90%), lesions present at birth or develop during the first 2 weeks of life and can be confused with herpes simplex or impetigo, which was the case with this study’s patient too.18,19

Stage 2, the verrucous stage, is characterized by plaques and warty papules. In most patients, these develop within 2–6 weeks and commonly vanish by 6 months of age.17

Stage 3, the hyperpigmented stage, is determined by the development of linear lesions with a brownish pigmentation, which will also follow the lines of Blaschko – as seen in this report (Figure 1).

Stage 4 is the atrophic or hypopigmented stage, which is characterized by areas of hypopigmentation, atrophy, and absence or loss of hair, most frequently observed on the lower extremities – as seen in the patient studied here also (Figure 1).20,21

According to the diagnostic criteria described by Landy and Donnai,8 the patient in this study had three major and two minor criteria. She matched the trends in presentation of the IP patient registry described by Fusco et al22 in most of the domains, except for CNS and ophthalmological defects.

One extremely rare complication of IP is PHTN, which has been reported in only five cases worldwide (Table 1), and was not included in the clinical domain of Fusco et al’s registry.22

Table 1.

Summary of IP cases with PHTN

| Clinical characteristics | Triki et al23 | Miteva and Nikolova24 | Hayes et al25 | Godambe et al10 | Yasuda et al26 | Present case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family history | Not mentioned | Abortion of male at 6 months’ gestation | Yes; mother and maternalgrandmother | Negative | Yes | Negative |

| Age of diagnosis of PHTN | 2 months | 6 months | 15 days | Immediately after birth | 2 months | Immediately after birth |

| Other cardiac anomaly | No | Tricuspid insufficiency and abnormal shunt of right pulmonary artery to superior vena cava | Right ventricular hypertrophy | First echo: PHTN, small atrial septal defect Second echo: – Dilated right ventricle – Marked tricuspid and pulmonary regurgitation |

Tricuspid valve regurgitation, severe right ventricular pressure elevation, patent foramen ovale | Atrial septal defect |

| Neurological | Convulsions on the fifth day of life. Brain CT scan showed diffuse hypodensities in the left hemisphere | Microcephaly, seizure, and hypotonia | Brain MRI showed multiple small areas of petechial hemorrhage. There was an area of cystic encephalomalacia in the right frontal lobe. The septum pellucidum was absent, with fusion of the fornices | Brain MRI showed polymicrogyria in the perisylvian area with cortical dysplasia | Neonatal seizures, multiple cerebral infarctions, multicystic encephalomalacia | Normal |

| Eyes | Not mentioned | Strabismus | Normal | Unilateral temporal avascular retina in zone III and bilateral peripheral straightened vessels and retinal hemorrhages | Not mentioned | Normal |

| Teeth | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Missing teeth, conoid teeth |

| Hair | Not mentioned | Normal | Not mentioned | Large patch of alopecia on the scalp | Not mentioned | Wooly hair |

| Nails | Not mentioned | Normal | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Normal |

| Other anomalies or complications | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Right hand was absent (acheiria) | GERD | ||

| Gene test | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Confirmed | Confirmed | Confirmed |

| Eosinophil | Not mentioned | 26% | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Hypereosinophilia (34 500/μL) | 1.40% |

| Mortality | Died at 2 months of age | Alive at 6/12 months (at the time of publication) | Died on day 47 of life | Died on day 26 of life | Died at 5 months of age | Still alive at 3 years of age |

Abbreviations: IP, incontinentia pigmenti; PHTN, pulmonary hypertension; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

The first case that reported the association between primary PHTN and IP was published in 1992, where the meticulously described baby died at 2 months of age. In addition, he had convulsions on the fifth day of life and a brain CT scan showed diffuse hypodensities in the left hemisphere.23

The second case was reported by Miteva and Nikolova.24 The patient was a female, who presented after birth with typical skin manifestations with neurological and ophthalmological symptoms. The patient’s cardiac anomalies included massive tricuspid insufficiency and abnormal shunt from the right pulmonary vein to the superior vena cava in addition to PHTN.

A third case reported by Hayes et al25 was familial with a positive family history of IP. This case was characterized by unilateral acheiria and was associated with CNS manifestations. In addition to the early diagnosed PHTN at the age of 15 days, she had right ventricular hypertrophy. Unfortunately, she died at 45 days of life.

Godambe et al10 reported the fourth case in the literature. The patient was a sporadic case in the family. She had typical skin lesions and developed cyanotic spells shortly after birth which led to a diagnosis of PHTN. Further investigations revealed ophthalmological manifestations. Follow-up echocardiography showed dilated right ventricle and marked tricuspid and pulmonary regurgitation. She received prostaglandin infusion initially followed by nitric oxide inhalation. The patient improved temporarily, then deteriorated again. Her condition continued to worsen despite treatment, and she died at 26 days of life.

The latest case was reported in 2016 by Yasuda et al. The case presented early in life with typical skin lesions, seizures, and multiple cerebral infarcts and encephalomalacia. She was found to have congenital heart disease and pulmonary hypertension at 2 months of age. Her case was unresponsive to medical treatment (oral bosentan) and she died at 5 months of age owing to severe pulmonary hypertensive crisis.26

Compared with previous cases, the patient in this case report did not manifest any neurological or ophthalmological complications of the disease. She shared clinical features of the fourth case in terms of the cyanotic spells.

Apparently, the patient studied in this report is the only case among the other reported cases that responded well to medical treatment and remained stable.

Although the exact explanation of PHTN associated with IP remains unknown, many proposed explanations have been attributed to dysfunction in the NF-κB pathway.27–29 However, the hypoplasia of the pulmonary arteries and the obstruction of the arterioles described in the cardiac catheterization for the patient in this study might indicate vasculopathy. This was proposed previously to be a cause of PHTN, CNS manifestations,30 and retinopathy, as described by Hennel et al,31 and Yasuda et al26 proposed diffuse microvasculopathy. However, Maingay-de Groof et al2 postulated macrovasculopathy in the medium and small arteries.

The variability in phenotype among IP patients with PHTN could be explained by lionization, proposed previously to explain the partial involvement pattern found in the skin and other organs in IP patients.32

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is growing evidence that IP can be associated with pulmonary hypertension of variable severity, which can be attributed to the dysfunction of the NF-κB pathway, resulting in progressive vasculopathy.

Acknowledgments

Written informed consent has been provided by the parents to have the case details and any accompanying images published. We are grateful to the family and patient reported in this article for their genuine support.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Smahi A, Courtois G, Vabres P, et al. Genomic rearrangement in NEMO impairs NF-kappaB activation and is a cause of incontinentia pigmenti. The International Incontinentia Pigmenti (IP) Consortium. Nature. 2000;405(6785):466–472. doi: 10.1038/35013114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maingay-de Groof F, Lequin MH, Roofthooft DW, et al. Extensive cerebral infarction in the newborn due to incontinentia pigmenti. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2008;12(4):284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jin DY, Jeang KT. Isolation of full-length cDNA and chromosomal localization of human NF-kappaB modulator NEMO to Xq28. J Biomed Sci. 1999;6(2):115–120. doi: 10.1007/BF02256442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beinke S, Robinson MJ, Hugunin M, Ley SC. Lipopolysaccharide activation of the TPL-2/MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade is regulated by IkappaB kinase-induced proteolysis of NF-kappaB1 p105. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(21):9658–9667. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9658-9667.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou H, Wertz I, O’Rourke K, et al. Bcl10 activates the NF-kappaB pathway through ubiquitination of NEMO. Nature. 2004;427(6970):167–171. doi: 10.1038/nature02273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-kappaB. Genes Dev. 2004;18(18):2195–2224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson DL. NEMO, NFkappaB signaling and incontinentia pigmenti. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16(3):282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landy SJ, Donnai D. Incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch–Sulzberger syndrome) J Med Genet. 1993;30(1):53–59. doi: 10.1136/jmg.30.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minic S, Trpinac D, Obradovic M. Incontinentia pigmenti diagnostic criteria update. Clin Genet. 2014;85(6):536–542. doi: 10.1111/cge.12223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Godambe S, McNamara P, Rajguru M, Hellmann J. Unusual neonatal presentation of incontinentia pigmenti with persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn: a case report. J Perinatol. 2005;25(4):289–292. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steffann J, Raclin V, Smahi A, et al. A novel PCR approach for prenatal detection of the common NEMO rearrangement in incontinentia pigmenti. Prenat Diagn. 2004;24(5):384–388. doi: 10.1002/pd.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakata S, Imai Y, Takanashi Y, et al. A new method for the quantitative standardization of cross-sectional areas of the pulmonary arteries in congenital heart diseases with decreased pulmonary blood flow. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1984;88(4):610–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Courtois G, Smahi A, Israel A. NEMO/IKK gamma: linking NF-kappa B to human disease. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7(10):427–430. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buinauskaite E, Buinauskiene J, Kucinskiene V, Strazdiene D, Valiukeviciene S. Incontinentia pigmenti in a male infant with Klinefelter syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27(5):492–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poziomczyk CS, Recuero JK, Bringhenti L, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(1):26–36. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fusco F, Paciolla M, Napolitano F, et al. Genomic architecture at the Incontinentia Pigmenti locus favours de novo pathological alleles through different mechanisms. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(6):1260–1271. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berlin AL, Paller AS, Chan LS. Incontinentia pigmenti: a review and update on the molecular basis of pathophysiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(2):169–187. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.125949. quiz 188–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okan F, Yapici Z, Bulbul A. Incontinentia pigmenti mimicking a herpes simplex virus infection in the newborn. Childs Nerv Syst. 2008;24(1):149–151. doi: 10.1007/s00381-007-0406-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Leeuwen RL, Wintzen M, van Praag MC. Incontinentia pigmenti: an extensive second episode of a “first-stage” vesicobullous eruption. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17(1):70. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2000.017001070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadj-Rabia S, Froidevaux D, Bodak N, et al. Clinical study of 40 cases of incontinentia pigmenti. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(9):1163–1170. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.9.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phan TA, Wargon O, Turner AM. Incontinentia pigmenti case series: clinical spectrum of incontinentia pigmenti in 53 female patients and their relatives. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30(5):474–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2005.01848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fusco F, Paciolla M, Conte MI, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: report on data from 2000 to 2013. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:93. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-9-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Triki C, Devictor D, Kah S, et al. Cerebral complications of incontinentia pigmenti. A clinicopathological study of a case. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1992;148(12):773–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miteva L, Nikolova A. Incontinentia pigmenti: a case associated with cardiovascular anomalies. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18(1):54–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2001.018001054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayes IM, Varigos G, Upjohn EJ, Orchard DC, Penny DJ, Savarirayan R. Unilateral acheiria and fatal primary pulmonary hypertension in a girl with incontinentia pigmenti. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;135(3):302–303. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yasuda K, Minami N, Yoshikawa Y, Taketani T, Fukuda S, Yamaguchi S. Fatal pulmonary arterial hypertension in an infant girl with incontinentia pigmenti. Pediatr Int. 2016;58(5):394–396. doi: 10.1111/ped.12831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belaiba RS, Bonello S, Zahringer C, et al. Hypoxia up-regulates hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha transcription by involving phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and nuclear factor kappaB in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(12):4691–4697. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-04-0391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamid R, Newman JH. Evidence for inflammatory signaling in idiopathic pulmonary artery hypertension: TRPC6 and nuclear factor-kappaB. Circulation. 2009;119(17):2297–2298. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.855197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woods M, Wood EG, Bardswell SC, et al. Role for nuclear factor-kappaB and signal transducer and activator of transcription 1/interferon regulatory factor-1 in cytokine-induced endothelin-1 release in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64(4):923–931. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.4.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ridder DA, Wenzel J, Muller K, et al. Brain endothelial TAK1 and NEMO safeguard the neurovascular unit. J Exp Med. 2015;212(10):1529–1549. doi: 10.1084/jem.20150165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hennel SJ, Ekert PG, Volpe JJ, Inder TE. Insights into the pathogenesis of cerebral lesions in incontinentia pigmenti. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;29(2):148–150. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(03)00150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rott HD. Extracutaneous analogies of Blaschko lines. Am J Med Genet. 1999;85(4):338–341. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19990806)85:4<338::aid-ajmg5>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]