Abstract

Tung tree (Vernicia fordii) is an economically important tree widely cultivated for industrial oil production in China. To better understand the molecular basis of tung tree chloroplasts, we sequenced and characterized its genome using PacBio RS II sequencing platforms. The chloroplast genome was sequenced with 161,528 bp in length, composed with one pair of inverted repeats (IRs) of 26,819 bp, which were separated by one small single copy (SSC; 18,758 bp) and one large single copy (LSC; 89,132 bp). The genome contains 114 genes, coding for 81 protein, four ribosomal RNAs and 29 transfer RNAs. An expansion with integration of an additional rps19 gene in the IR regions was identified. Compared to the chloroplast genome of Jatropha curcas, a species from the same family, the tung tree chloroplast genome is distinct with 85 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and 82 indels. Phylogenetic analysis suggests that V. fordii is a sister species with J. curcas within the Eurosids I. The nucleotide sequence provides vital molecular information for understanding the biology of this important oil tree.

Introduction

Tung tree (Vernicia fordii) belongs to the Euphorbiaceae family of woody angiosperms and has been cultivated for more than 1,000 years in China. Along with oil-tea tree (Camellia oleifera), walnut (Juglans regia) and Chinese tallow tree (Sapium sebiferum), tung tree is considered as one of the four major woody oil trees in China1, 2. Tung tree grows fast, blossoms and yields fruits in three years due to its high efficiency of photosynthesis. Tung oil extracted from seed kernels containing 80% eleostearic acid, which is active for chemical polymerization1, and can be used as an ingredient in painting, varnishing, and other coating for enhancing adhesion and resistance to acid, alkali, frost and chemicals3. In recent years, tung oil has been shown with a potential for biodiesel production because tung tree grows fast with high oil yields1, 4. One approach to improve tung oil production would be to engineer chloroplasts with more efficient photosynthesis in tung tree leaves. Sequencing the complete chloroplast genome would facilitate the chloroplast transformation technique because the transformation of chloroplast genome has many advantages than nuclear transformation including a high level of transgene expression, lacking of gene silencing or positional effect and transgene containment5–7.

Chloroplast (cp) is a special subcellular organelle which contains the entire enzymatic machinery for photosynthesis and provides essential energy for green plants8–10. Chloroplast contains its own small genome, which usually consists of a circular double-stranded DNA molecule10, 11. In angiosperms, cp genomes are 120–217 kb in length12, 13. Most of the cp genomes contain 110–130 distinct genes, approximately 80 genes coding for proteins involved in gene expression or photosynthesis10, 14 and other genes coding for four rRNAs and 30 tRNAs15, 16. In addition, most cp genomes have four distinct regions, including a pair of inverted repeats (IRs, 20–28 kb), which are separated by a small single copy (SSC, 16–27 kb) region and a large single copy (LSC, 80–90 kb) region14, 17, 18. The cp genome can be used to investigate molecular evolution and phylogenies14, 19. Moreover, cp genomes are maternally inherited, which is beneficial in genetic engineering due to lack of cross-recombination20, 21.

In this study, we determined the complete sequence of the chloroplast genome of tung tree using the PacBio RS II platform. Additionally, we compared it with other known cp genomes aiming to determine phylogenetic relationships among angiosperms.

Results

Genome sequencing, assembly and validation

Using the third-generation sequencing (PacBio RS II System), 18.26 Gb of raw sequence data was generated from tung tree cp genome through 2,910,237 reads with a mean read length of 6,273 bp. The sequence data that satisfied the quality control standards after filtering, were used to construct the cp genome by comparing with the reference cp genomes of other 908 species in NCBI plastid database. The longest recovered subread was 35,889 bp in length and the total amount of recovered subreads was 334 Mb. The depth of average genome coverage of the subreads exceeded 2000X, suggesting that the sequencing data was sufficient to meet the assembly requirements for cp genome. Finally, we obtained 2.4 M high quality reads with a mean read length of 6,762 bp and an N50 contig size of 17,719 bp. The results showed a high consensus of the sequences except 10 different bases between IRa and IRb regions. To ensure the accuracy for the tung tree cp genome, we compared the Sanger results with the assembled genome. The sequence of tung tree cp genome has been deposited in public databases (Genbank accession number: KY628420).

General features of tung tree cp genome

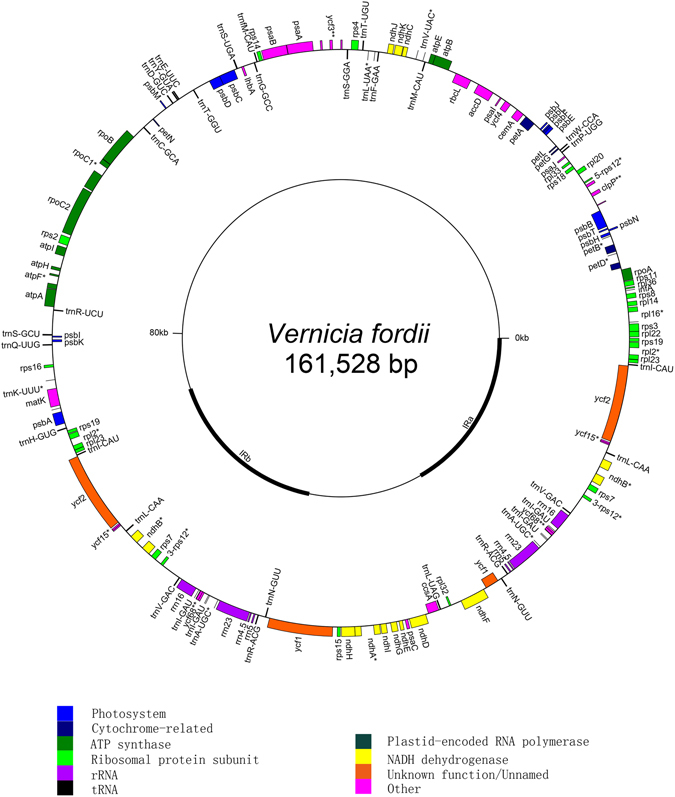

The total length of tung tree cp genome was determined to be 161,528 bp with the circular quadripartite structure similar to major angiosperms cp genomes. The cp genome contains a small single-copy (SSC) region of 18,758 bp and a large single-copy (LSC) region of 89,132 bp, separated by two copies of an inverted repeat (IR) of 26,819 bp (Fig. 1, Table 1). The genome is structured with 114 unique genes including 81 distinct protein-coding genes, four distinct rRNA genes and 29 distinct tRNA genes (Table 2). Seven tRNA genes and all of the rRNA genes are duplicated in the IR regions, making a total number of 135 genes (Tables 1 and 2). The genes coding for proteins, rRNA, tRNA, introns, and intergenic spacers (IGSs) are 82,034, 9048, 2742, 17,821, and 52,599 bp, which represent 50.79, 5.60, 1.70, 11.03, and 32.56% of the cp genome, respectively (Table 1). In this cp genome, 16 genes including 5 tRNA genes contain introns structure (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Gene map of tung tree chloroplast genome from PacBio RS II platform. The thick lines indicate the inverted repeats (IRa and IRb) which separate the genome into large single copy (LSC) and small single copy (SSC) regions. Genes shown in the inner side of the circle are transcribed clockwise, and those located on the outside of the circle are transcribed counter-clockwise.

Table 1.

Characteristics of tung tree plastome genome.

| Sequence region | Length (bp)/Percent (%) |

|---|---|

| Total cp genome | 161,528 (100.00) |

| LSC | 89,132 (55.18) |

| SSC | 18,758 (11.61) |

| IR | 26,819 (16.60) |

| Coding regions | 91,388 (57.20) |

| Protein-coding regions | 82,034 (50.79) |

| Introns | 17,821 (11.03) |

| rRNA | 9,048 (5.60) |

| tRNA | 2,742 (1.70) |

| IGS | 52,599 (32.56) |

| GC content | Length (bp)/Percent (%) |

| Overall GC size | 58,188 (36.02) |

| Overall A size | 52,378 (32.43) |

| Overall T size | 50,962 (31.55) |

| Overall G size | 29,615 (18.33) |

| Overall C size | 28,573 (17.69) |

| GC content in protein-coding regions | 30,780 (37.52) |

| GC content in IGS | 15,394 (29.27) |

| GC content in introns | 6,595 (37.01) |

| GC content in tRNA | 2,742 (53.17) |

| GC content in rRNA | 5,014 (55.42) |

| Gene classification | Number |

| Total genes | 135 |

| Protein-coding genes | 81 |

| rRNA genes | 4 |

| tRNA genes | 29 |

| Genes with introns | 16 |

| Genes duplicated by IR | 21 |

Table 2.

Genes locating on tung tree cp genome.

| Gene categories | Groups of genes | Name of genes |

|---|---|---|

| Genes for photosynthesis | Subunits of photosystem I | psaA, psaB, psaC, psaI, psaJ |

| Subunits of photosystem II | psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbL, psbM, psbN, psbT | |

| Subunits of ATP synthase | atpA, atpB, atpE, atpF b , atpH, atpI | |

| Subunits of cytochrome b/f complex | petA, petB b , petD b , petG, petL, petN | |

| Subunits of NADH-dehydrogenase | ndhA b , ndhB a,b , ndhC, ndhD, ndhE, ndhF, ndhG, ndhH, ndhI, ndhJ, ndhK | |

| Large subunit of RuBisco | rbcL | |

| Self replication | Ribosomal RNAs | rrn16 a , rrn23 a , rrn4.5 a , rrn5 a |

| Transfer RNAs | trnA-UGC a,b , trnC-GCA, trnD-GUC, trnE-UUC, trnF-GAA, trnG-GCC, trnH-GUG, trnI-CAU a , trnI-GAU a,b , trnK-UUU b , trnL-CAA a , trnL-UAA b , trnL-UAG, trnM-CAU, trnfM-CAU, trnN-GUU a , trnP-UGG, trnQ-UUG, trnR-UCU, trnR-ACG a , trnS-UGA, trnS-GGA, trnS-GCU, trnT-GGU, trnT-UGU, trnW-CCA, trnY-GUA, trnV-UAC b , trnV-GAC a | |

| Proteins of small ribosomal subunit | rps2, rps3, rps4, rps7 a , rps8, rps11, rps12 a,b , rps14, rps15, rps16, rps18, rps19 a | |

| Proteins of large ribosomal subunit | rpl2 a,b , rpl14, rpl16 b , rpl20, rpl22, rpl23 a , rpl32, rpl33, rpl36 | |

| Subunits of RNA polymerase | rpoA, rpoB, rpoC1 b , rpoC2 | |

| Other genes | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase | accD |

| Cytochrome c biogenesis | ccsA | |

| Envelope membrane protein | cemA | |

| Maturase | matK | |

| Protease | clpP b | |

| Translation initiation factor | infA | |

| Unknown | Conserved hypothetical chloroplast reading frames | ycf1 a , ycf2 a , ycf3 b , ycf4, ycf15 a , ycf68 a , lhbA |

aGenes located in the IR regions.

bGenes having introns.

Comparison to the cp genomes from other Euphorbiaceae species

The size of the tung tree cp genome was found to be similar to those from Euphorbiaceae family species, J. curcas, H. brasiliensis and M. esculenta (Table 3). However, tung tree cp genome has the longest SSC region (18,758 bp), whereas J. curcas has the shortest SSC region (17,852 bp). Tung tree cp genome contains more genes (135) than other species, and among them 21 genes duplicated in IRs, while 16 genes duplicated in M. esculenta. As shown in Table 3, tung tree has the highest GC content (36.02%), while J. curcas has the lowest GC content (35.36%). Four conserved rRNAs were identified in every species. J. curcas and H. brasiliensis contain 78 coding genes, whereas M. esculenta has 79, and tung tree has 81 coding genes. Tung tree cp genome encodes 29 types of tRNAs, whereas H. brasiliensis and M. esculenta encode 30 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of general features of Euphorbiaceae plastid genomes.

| Genome feature | Vernicia fordii | Jatropha curcas | Hevea brasiliensis | Manihot esculenta |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total length (bp) | 161528 | 163856 | 161191 | 161453 |

| LSC length (bp) | 89132 | 91756 | 89209 | 89295 |

| SSC length (bp) | 18758 | 17852 | 18362 | 18250 |

| IR length (bp) | 26819 | 27124 | 26810 | 26954 |

| GC content (%) | 36.02 | 35.36 | 35.74 | 35.87 |

| Total genes | 135 | 130 | 128 | 128 |

| Genes duplicated in IR | 21 | 17 | 19 | 16 |

| rRNA gene duplicated in IR | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Protein gene | 81 | 78 | 78 | 79 |

| tRNA gene | 29 | 28 | 30 | 30 |

| rRNA gene | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

Repeat sequence analysis

The tung tree cp genome encloses 49 repeats with at least 21 base pairs (bp) per repeat unit (Table 4). These repeats include two complementary repeats, 21 direct (forward) repeats, 16 inverted (palindrome) repeats and 10 reverse repeats have 1,504 bp in length, which is about 0.93% of the genome. Most of these repeats are located in intergenic regions, while 8 repeats are located in the introns and in the protein-coding genes including psaA, ycf1 and ycf2.

Table 4.

Repeat sequences in the tung tree cp genome.

| No. | Length (bp) | Repeat type | Repeat 1 start position | Repeat 2 start position | Repeat 1 location | Repeat 2 location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22 | C | 48854 | 78423 | trnfM-CAU_trnS-UGA | trnfM-CAU_trnS-UGA |

| 2 | 26 | C | 104466 | 146168 | ycf15_trnV-GAC | ycf15_trnV-GAC |

| 3 | 21 | F | 7396 | 146181 | rpoA_psbN | rpoA_psbN |

| 4 | 24 | F | 25372 | 25405 | psbJ_atpB | psbJ_atpB |

| 5 | 67 | F | 33717 | 33766 | trnV-UAC_ndhC | trnV-UAC_ndhC |

| 6 | 29 | F | 33738 | 33833 | trnV-UAC_ndhC | trnV-UAC_ndhC |

| 7 | 29 | F | 33787 | 33833 | trnV-UAC_ndhC | trnV-UAC_ndhC |

| 8 | 35 | F | 43695 | 45919 | psaA | psaA |

| 9 | 53 | F | 53710 | 75960 | trnS-UGA_trnE-UUC | trnS-UGA_trnE-UUC |

| 10 | 23 | F | 55290 | 55312 | trnS-UGA_trnE-UUC | trnS-UGA_trnE-UUC |

| 11 | 23 | F | 56751 | 56772 | trnD-GUC_psbM | trnD-GUC_psbM |

| 12 | 30 | F | 78078 | 78104 | atpA_trnS-GCU | atpA_trnS-GCU |

| 13 | 26 | F | 78159 | 78176 | atpA_trnS-GCU | atpA_trnS-GCU |

| 14 | 34 | F | 78333 | 78353 | atpA_trnS-GCU | atpA_trnS-GCU |

| 15 | 25 | F | 83781 | 83806 | rps16_trnK-UUU | rps16_trnK-UUU |

| 16 | 22 | F | 83784 | 83831 | rps16_trnK-UUU | rps16_trnK-UUU |

| 17 | 23 | F | 83809 | 83831 | rps16_trnK-UUU | rps16_trnK-UUU |

| 18 | 62 | F | 96620 | 96656 | ycf2 | ycf2 |

| 19 | 26 | F | 96620 | 96692 | ycf2 | ycf2 |

| 20 | 26 | F | 117126 | 117141 | ycf1 | ycf1 |

| 21 | 25 | F | 134591 | 134653 | ndhF_trnN-GUU | ndhF_trnN-GUU |

| 22 | 62 | F | 153942 | 153978 | trnL-CAA_trnI-CAU | trnL-CAA_trnI-CAU |

| 23 | 26 | F | 153942 | 154014 | trnL-CAA_trnI-CAU | trnL-CAA_trnI-CAU |

| 24 | 21 | P | 7396 | 104458 | rpoA_psbN | rpoA_psbN |

| 25 | 24 | P | 22678 | 22678 | psbJ_atpB | psbJ_atpB |

| 26 | 22 | P | 33682 | 33682 | trnV-UAC_ndhC | trnV-UAC_ndhC |

| 27 | 29 | P | 39744 | 80476 | rps4_ycf3 | rps4_ycf3 |

| 28 | 21 | P | 39749 | 49846 | rps4_ycf3 | rps4_ycf3 |

| 29 | 26 | P | 48023 | 48023 | trnfM-CAU_trnS-UGA | trnfM-CAU_trnS-UGA |

| 30 | 22 | P | 48862 | 79778 | trnfM-CAU_trnS-UGA | trnfM-CAU_trnS-UGA |

| 31 | 52 | P | 57302 | 57302 | psbM_rpoB | psbM_rpoB |

| 32 | 22 | P | 74732 | 74732 | atpH_atpF | atpH_atpF |

| 33 | 58 | P | 89003 | 89003 | trnH-GUG_ycf2 | trnH-GUG_ycf2 |

| 34 | 62 | P | 96620 | 153942 | ycf2 | ycf2 |

| 35 | 26 | P | 96620 | 153942 | ycf2 | ycf2 |

| 36 | 62 | P | 96656 | 153978 | ycf2 | ycf2 |

| 37 | 26 | P | 96692 | 154014 | ycf2 | ycf2 |

| 38 | 22 | P | 117973 | 117973 | ycf1 | ycf1 |

| 39 | 28 | P | 131410 | 131410 | ndhD_ndhF | ndhD_ndhF |

| 40 | 23 | R | 4544 | 4544 | rpl36_rps11 | rpl36_rps11 |

| 41 | 21 | R | 19798 | 19798 | trnW-CCA_psbE | trnW-CCA_psbE |

| 42 | 21 | R | 22672 | 22672 | psbJ_atpB | psbJ_atpB |

| 43 | 24 | R | 48637 | 48637 | trnfM-CAU_trnS-UGA | trnfM-CAU_trnS-UGA |

| 44 | 26 | R | 65276 | 65276 | rpoC1 | rpoC1 |

| 45 | 22 | R | 78009 | 78009 | atpA_trnS-GCU | atpA_trnS-GCU |

| 46 | 22 | R | 78029 | 78061 | atpA_trnS-GCU | atpA_trnS-GCU |

| 47 | 31 | R | 78030 | 78030 | atpA_trnS-GCU | atpA_trnS-GCU |

| 48 | 26 | R | 104466 | 104466 | ycf15_trnV-GAC | ycf15_trnV-GAC |

| 49 | 26 | R | 146168 | 146168 | trnN-GUU_rps7 | trnN-GUU_rps7 |

C: complement repeats, F: forward repeats, P: palindrome repeats, R: reverse repeats.

Simple sequence repeat (SSR) analysis

81 SSR loci were identified, including 63 mononucleotide SSR loci (77.78%), five dinucleotide SSR loci (6.17%), and 13 other types of SSR loci (16.05%). Among them, there are 79 A or T repeats, one G repeat and one AG dinucleotide repeat. These SSR loci represent 0.937% of the complete cp sequence. 64 of the 81 SSR loci are located in intergenic regions, eight in gene-coding regions, six in intron regions, two between the gene-coding and intron regions, and only one between the intergenic regions and gene codingregions (see Supplementary Table S1).

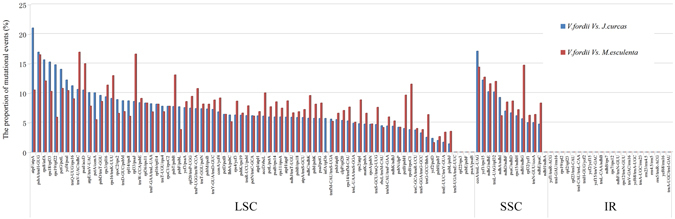

Variation analysis

By comparing with the cp genome sequences from V. fordii and J. curcas, a total of 85 SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) and 82 indels were identified. atpF/atpA is the most variable in the IGS within the LSC region (21.05% of variability). V. fordii and M. esculenta have identified 86 SNPs and 81 indels. Among them, 69 SNPs and 74 indels are within LSC region, 12 SNPs and seven indels are within SSC region. trnV-UAC/ndhC is the most variable in the IGS within the LSC region (16.96% of variability) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The variation analysis within intergenic spacer (IGS) regions between V. fordii and J. curcas or M. esculenta.

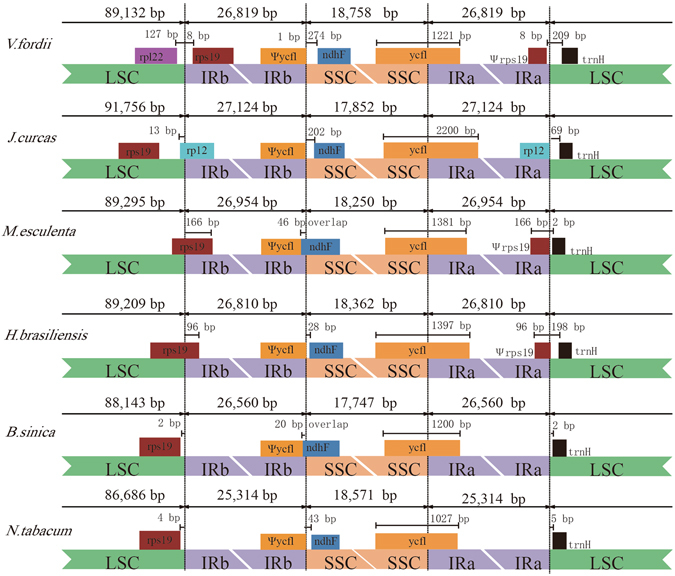

IR contraction and expansion

Although IRs are the most conserved regions in cp DNA, the expansion and contraction at the borders of the IR regions are common evolutionary events, causing size variation of cp genomes22, 23. The IR-LSC and IR-SSC borders of tung tree cp genome were compared to those of the five basal eudicots (J. curcas, M. esculenta, H. brasiliensis, B. sinica, and N. tabacum). In all plant species, the IRb/SSC borders extend into the ycf1 genes to create long ycf1 pseudogenes with variable length. The length of ycf1 pseudogene is 1,221 bp in tung tree, 2,200 bp in J. curcas, 1,397 bp in H. brasiliensis and 1,027 bp in N. tabacum. In addition, the ycf1 pseudogene and the ndhF gene overlap M. esculenta and B. sinica cp genomes by 46 bp and 20 bp, respectively, but the ndhF genes of the other 4 species are all located in the SSC region, and it ranges from 274 bp from the IRb/LSC border in tung tree cp genome (Fig. 3). The trnH-GIG sequences are found in LSC regions of all cp genomes. This gene is 209 bp from the IRa/LSC border in tung tree cp genome. The rps19 sequence is detected in the IR regions of tung tree cp genome and 8 bp apart from the LSC/IRb border, whereas this gene is located in the LSC in J. curcas, B. sinica and N. tabacum. In addition, the rps19 gene is observed at the IRb/LSC border of two Euphorbiaceae plants, M. esculenta and H. brasiliensis (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the border regions of LSC, IR and SSC among six chloroplast genomes of basal eudicots.

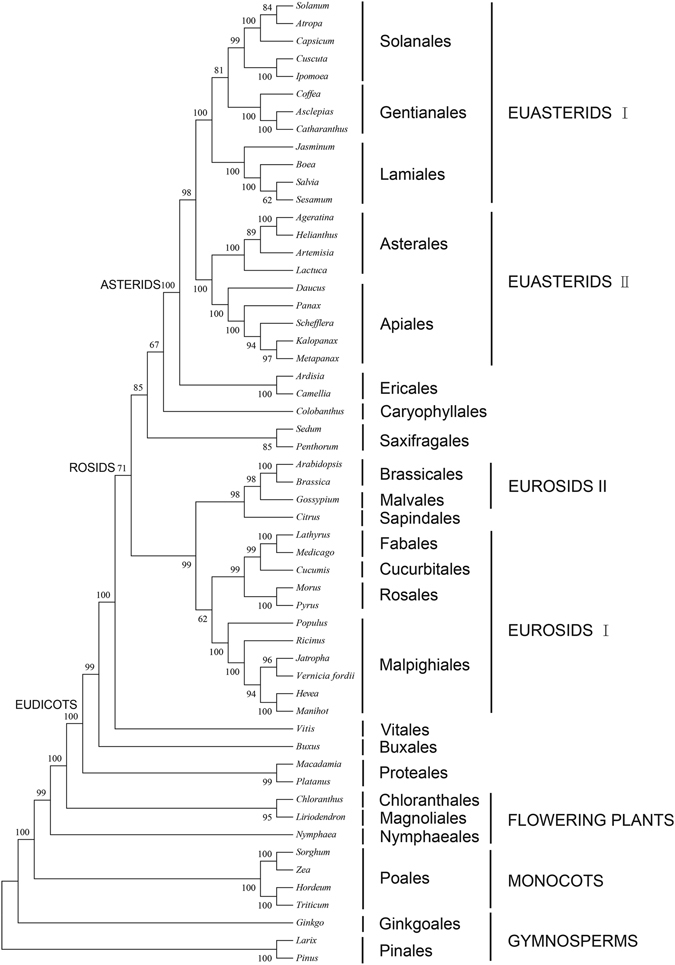

Phylogenetic Analysis

To analyze the V. fordii phylogenetic position within asterid lineage, we aligned 55 complete cp genome sequences using the 36 protein-coding genes. The species representing 24 orders and included 3 outgroup taxa. The sequence analysis showed a fully resolved phylogenetic tree (12,995 in length of 0.51 for consistency index and 0.65 for retention index) (Fig. 4). The phylogenetic trees generated by ML and MP alignment have similar topologies (Figs 4 and S1). There are a total of 7,609 positions in the final dataset. V. fordii is placed as sister to J. curcas with a bootstrap (96). V. fordii is grouped to Malpighiales with J. curcas. There is a sister relationship among Falales, Cucurbitalesand Rosales.

Figure 4.

The maximum parsimony (MP) phylogenetic tree based on 36 protein-coding genes in the chloroplast genome. The numbers in each node was tested by bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates.

Discussion

The entire chloroplast genome of tung tree was determined using the third-generation sequencing (PacBio RS II System) method and assembled with the chloroplast genomes of the other Euphorbiaceae plants using the cp genomes of J. curcas and M. esculenta as references. The genome sequence was confirmed by Sanger sequencing of PCR-based products using specific primers (see Supplementary Table S2). As shown in Figure 1, the tung tree cp genome is a typical circle DNA, similar to those from Euphorbiaceae7, 13, 24.

Repeat sequences are useful for studying genome rearrangement and play an important role in phylogenetic analysis25. There are 49 repeats in the tung tree cp genome. A large number of repeats are distributed within IGS regions and the IRs account for the majority of repeats. In addition, we also find many repeats are present in the ycf2 gene including two forward repeats and four palindrome repeats. The results are similar to those of previous studies on Jatropha curcas 13, Citrus sinensis 16 and Vitis26. Meanwhile, the non-coding regions in cp genomes are important for phylogenetic studies in angiosperms27. Most of the repeats are found in the non-coding regions of the tung tree cp genome.

In tung tree cp genome, 81 SSR loci with a length of at least 10 bp were identified (Table S1). All of the dinucleotides are composed of multiple copies of AT/TA repeats, and 75 of them are detected in the noncoding regions. These findings are similar to those of the other published results, i,e., repeats are typically found in the noncoding regions, especially in IGS regions of the cp genomes17, 28, 29. The SSRs in cp genomes was first reported in Pinus radiata 30. These SSRs can be useful biomarkers for genetic diversity.

The border regions of LSC-IRa, IRa-SSC, SSC-IRb and IRb-LSC represent highly variable regions with many nucleotide changes in cp genomes of closely related species. We compared the IR boundary regions of cp genome from six species in this study. The border of tung tree cp genome is differed slightly from that of other cp genomes. At the IRb and SSC border, the intergenic region of ycf1 and ndhF in tung tree cp genome is larger (274 bp) than those in other species13. In addition, the SSC region in tung tree cp genome is also larger than those in other species. The long distance of IRb and SSC border could be a result of the expanding chloroplast genome of tung tree. The rps19 gene of tung tree is entirely located in the IR regions, which is generally located in the LSC region or at the junction of LSC/IRb border in dicotyledons31–33. Previous studies have shown that rps19 sequence is generally positioned in the IR regions of cp genomes from monocotyledon pineapple (Ananas comosus)34, and Chionographis japonica 35. Our results indicate that the rps19 gene location is similar to monocotyledon. In Euphorbiaceae, though the IR region of tung tree cp genome is shorter than that of J. curcas and M. esculenta, it has more duplicated genes (21 genes) than those of J. curcas (17 genes) and M. esculenta (16 genes). The main reasons for these differences are that the rps19 gene is duplicated in IR regions and that the ycf15 and ycf68 genes are found in tung tree; which are consistent with those results obtained from Hevea brasiliensis 7 and Musa acuminata 36. Meanwhile, ycf15 and ycf68 genes were identified as pseudogenes in tung tree, and ycf68 sequence is found in the intron regions of trnI-GAU. The similar result has been reported in the cp genome sequence of Pelargonium hortorum 15.

It is reported that cp genomes in most land plants have two identical IR regions, which have lower the nucleotide substitution rates and fewer indels than LSC and SSC regions37. Similarly, few indels were identified in the IR regions of tung tree cp genome. IGSs and intron regions have more indels than protein-coding genes and thus evolve more quickly than protein-coding genes. Traditionally the nucleotide substitutions and indels in cp genomes have been used as DNA markers in the phylogenetic analysis of many land plants38–40.

In the Euphorbiaceae family several studies have analyzed the phylogenetic relationship based on chloroplast DNA sequences7, 13, 24. The phylogenetic evolution of V. fordii were studied here using 36 protein coding genes for 55 plant taxa (Supplementary Table S3), including 52 angiosperms and three outgroup gymnosperms (Ginkgo, Larix and Pinus). We used MP and ML analyses to construct an evolutionary tree involving 55 amino acid sequences. All 52 nodes were resolved well and reliable based on MP bootstrap value: 41 have strong bootstrap support of 95–100% and 11 have moderate support of 60–95%. V. fordii and the other four species in the family Euphorbiaceae are clustered into Malpighiales as a well-supported monophyly and placed within Eurosids I, which is similar to pervious work41. The phylegenetic tree indicates that subfamily Crotonoideae is a younger, more evolved group than subfamily Acalyphoideae (i.e. Ricinus in this study). However, the deep phylogeny within angiosperms differ from previous research in several ways42, 43. In our analysis, monocots forms a sister group to the remaining angiosperms, although it is often embedded in dicots in other studies. One possible reason is the heterogeneity between the nuclear and chloroplast genomes44, 45. There are a few disparities between the MP and ML trees in our analyses. This might be because maximum parsimony is sensitive to incongruent evolutionary rates at internal nodes46. In addition, V. fordii is suggested to be more closely related to Jatropha than to Hevea and Manihot.

Conclusion

We presented the first complete nucleotide sequence of tung tree cp genome using PacBio RS II sequencing platforms. The tung tree cp genome (161,528 bp) was fully characterized and compared to the cp genomes of related species. We identified two inverted repeat regions and one small and one large single copy regions. The tung tree cp genome contained 114 unique genes coded for 81 proteins, four ribosomal RNAs and 29 transfer RNAs. Phylogenetic analysis suggests that V. fordii is a sister species of J. curcas within the Eurosids I. Our study provides vital molecular information for understanding of the cp genome of this commercially important woody oil tree.

Material and Methods

Plant materials and DNA sequencing

Tung tree leaves were obtained from a two years old self-bred progeny plant at Central South University of Forestry and Technology Germplasm Repository (CSUFTGR) (110° 29′ E, 28° 32′ N, Yong Shun, Ji Shou, Hunan, China). Based on the manufacturer’s instructions, the whole genomic DNA was extracted from 5 g of fresh leaves with DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN, CA, USA). After DNA was purified, 5 mg was used in library construction. In addition, a PacBio RS II platform47 was used for sequencing tung tree cp genome (Nextomics, Wu Han, China).

Genome assembly and annotation

All sequenced reads were filtered through removing the adapter sequence and cutting off low quality bases in reads and assembled by HGAP 2.3.0 process48, Celera assembler (CA) assembled software49 and OLC assembly algorithm50. The cp genome was annotated using Dual Organellar GenoMe Annotator (DOGMA)51 and CPGAVAS (http://www.herbalgenomics.org/0506/cpgavas/analyzer/annotate). The predicted annotations were confirmed by BLAST52 search against the nucleotide database of NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf). Uncertain annotations for protein-coding sequences, tRNAs and mRNAs genes were corrected after being compared with near edge species.

Genome Validation

Because chloroplast genomes exhibit a greater degree of conservation in most of the plants, we compared the complete cp genome sequences among tung tree, Jatropha [NC_012224], and Manihot [EU117376] in NCBI plastid database. The sequence discrepancies between tung tree and Jatropha or Manihot cp genome sequences were validated by PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing. Ten different bases between IRa and IRb regions were also amplified by PCR. PCR were used to verify differences in the sequence of the preliminary cp genome assembly using 29 pairs of forward and reverse primers (see Supplementary Table S2).

Analysis of cp genome sequence

GenomeVx software53 was used to draw the circular map of the tung tree chloroplast genome. Mauve software12 and mVISTA program were applied to identify similarities among different cp genomes (http://genome.lbl.gov/vista/mvista/submit.shtml)54. REPuter55 was utilized to identify forward (direct) repeats, reverse sequences, complementary and palindromic sequences with at least 21 bp in length and 90% of sequence identity. The distributions of simple sequence repeats (SSRs) were predicted using the microsatellite search tool MISA56. Insertions and deletions (indels), as well as nucleotide substitutions and inversions were scored as single independent characters. The formula (NS + ID)/L × 100 (NS, nucleotide substitutions number; ID, indels number; L, the aligned sequence length) was used to calculate the ratio of mutation events. In addition, the contraction/expansion regions of the inverted repeat (IR) were compared among V. fordii, J. curcas, M. esculenta, H. brasiliensis, B. sinica, and N. tabacum.

Phylogenetic analysis

Fifty-two angiosperm and three gymnosperm taxa typically possess a set of 36 protein-coding genes: atpA, atpB, atpE, atpH, atpI, petA, petB, petD, petG, petN, psaA, psaB, psaJ, psbA, psbC, psbD, psbF, psbH, psbJ, psbK, psbM, psbN, psbT, matK, rbcL, rpl33, rpoA, rpoB, rps2, rps3, rps4, rps8, rps18, rps11, rps14, and ccsA. These genes are present in all 55 cp genomes published in the NCBI database (see Supplementary Table S3). The maximum parsimony (MP) and maximum likelihood (ML) were performed to infer the evolutionary relationship. MUSCLE57 was used to align sequences followed by manual adjustment. MEGA*6.058 was used for MP analysis using a heuristic search selected. Bootstrap analysis was done with 1,000 replicates with TBR branch swapping. ML analysis was conducted using FastTree v2.1.359, 60 with the default parameters. The nucleotide substitution model we chose was GTRGAMMA model, which was the common model reported in the literature. The 1000 replications were used to calculate local bootstrap probability of each branch.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Forestry Public Welfare Industry Research Project of China (201204403) and USDA-ARS Quality and Utilization of Agricultural Products Research Program 306 through CRIS 6435-41000-102-00D.

Author Contributions

Ze Li analyzed the results. Hongxu Long prepared plant materials and collected the samples. Lin Zhang prepared tables 1–4 and supplementary materials. Heping Cao prepared figures 1–4 and revised the manuscript. Ze Li, Zhiming Liu, Mingwang Shi and Xiaofeng Tan wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-02076-6

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mingwang Shi, Email: shimw888@126.com.

Xiaofeng Tan, Email: tanxiaofengcn@126.com.

References

- 1.Tan XF, et al. Research report on industrialization development strategy of Vernicia fordii in China. Nonwood Forest Research. 2011;29:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu W, Yang W, Huai H, Liu A. Microsatellite marker development in tung trees (Vernicia montana and V. fordii, Euphorbiaceae) Am. J. Bot. 2011;98:226–228. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1100151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao HP, Shockey JM. Comparison of TaqMan and SYBR Green qPCR methods for quantitative gene expression in tung tree tissues. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2012;60:12296–12303. doi: 10.1021/jf304690e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen YH, Chen JH, Chang CY, Chang CC. Biodiesel production from tung (Vernicia montana) oil and its blending properties in different fatty acid compositions. Bioresource Technology. 2010;101:9521–9526. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.06.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maliga P. Plastid transformation in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004;55:289–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bock R. Plastid biotechnology: prospects for herbicide and insect resistance, metabolic engineering and molecular farming. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 2007;18:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tangphatsornruang S, et al. Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of Hevea brasiliensis reveals genome rearrangement, RNA editing sites and phylogenetic relationships. Gene. 2011;475:104–12. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darling AC, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang M, et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terakami S, et al. Complete sequence of the chloroplast genome from pear (Pyrus pyrifolia): genome structure and comparative analysis. Tree Genet. Genomes. 2012;8:841–854. doi: 10.1007/s11295-012-0469-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmer J. Comparative organization of chloroplast genomes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1985;19:325–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.19.120185.001545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ravi V, Khurana JP, Tyagi AK, Khurana P. The chloroplast genome of mulberry: complete nucleotide sequence, gene organization and comparative analysis. Tree Genet. Genomes. 2006;3:49–59. doi: 10.1007/s11295-006-0051-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asif MH, et al. Complete sequence and organisation of the Jatropha curcas (Euphorbiaceae) chloroplast genome. Tree Genet. Genomes. 2010;6:941–952. doi: 10.1007/s11295-010-0303-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raubeson, L. A. & Jansen, R. K. Chloroplast genomes of plants. In: Henry R. (ed) Diversity and evolution of plants—genotypic and phenotypic variation in higher plants. CABI, Wallingford, 45–68 (2005).

- 15.Chumley TW, et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Pelargonium × hortorum: organization and evolution of the largest and most highly rearranged chloroplast genome of land plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006;23:2175–2190. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bausher MG, Singh ND, Lee SB, Jansen RK, Daniell H. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck var ‘ridge pineapple’: organization and phylogenetic relationships to other angiosperms. BMC Plant Biol. 2006;6:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-6-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang L, Wuyun TN, Du HY, Wang DP, Cao D. Complete chloroplast genome sequences of Eucommia ulmoides: genome structure and evolution. Tree Genet. Genome. 2016;12:12. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao X, et al. Chloroplast genome structure in Ilex (Aquifoliaceae) Sci. Rep. 2016;6:28559. doi: 10.1038/srep28559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asif H, et al. The chloroplast genome sequence of Syzygium cumini (L.) and its relationship with other angiosperms. Tree Genet. Genome. 2013;9:867–877. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maliga P. Engineering the plastid genome of higher plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002;5:164–172. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00248-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tangphatsornruang S, et al. The chloroplast genome sequence of mungbean (Vigna radiata) determined by High-throughput Pyrosequencing: structural organization and phylogenetic relationships. DNA Res. 2010;17:11–22. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsp025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raubeson LA, et al. Comparative chloroplast genomics: analyses including new sequences from the angiosperms Nuphar advena and Ranunculus macranthus. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:174. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang RJ, Cheng CL, Chang CC, Chaw SM. Dynamics and evolution of the inverted repeat-large single copy junctions in the chloroplast genomes of monocots. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008;8:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daniell H, et al. The complete nucleotide sequence of the cassava (Manihot esculenta) chloroplast genome and the evolution of atpF in Malpighiales: RNA editing and multiple losses of a group II intron. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2008;116:723–737. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0706-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith TC. Chloroplast evolution: secondary symbiogenesis and multiple losses. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:62–64. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jansen RK, et al. Phylogenetic analyses of Vitis (Vitaceae) based on complete chloroplast genome sequences: effects of taxon sampling and phylogenetic methods on resolving relationships among rosids. BMC Evol. Biol. 2006;6:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Small RL, Ryburn JA, Cronn RC, Seelanan T, Wendel JF. The tortoise and the hare: choosing between non coding plastome and nuclear ADH sequences for phylogeny reconstruction in a recently diverged plant group. Am. J. Bot. 1998;85:1301–1315. doi: 10.2307/2446640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Provan J, Powell W, Hollingsworth PM. Chloroplast microsatellites: new tools for studies in plant ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2001;16:142–147. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)02097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sithichoke T, Pichahpuk U, Duangjai S. Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of Hevea brasiliensis reveals genome rearrangement, RNA editing sites and phylogenetic relationships. Gene. 2011;475:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Powell W, et al. Hypervariable microsatellites provide a general source of polymorphic DNA markers for the chloroplast genome. Curr. Biol. 1995;5:1023–1029. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(95)00206-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yi DK, Kim KJ. Complete chloroplast genome sequences of important oilseed crop Sesamum indicum L. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeong YM, Chung WH, Mun JH, Kim N, Yu HJ. De novo assembly and characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of radish (Raphanus sativus L.) Gene. 2014;551:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu Z, et al. A precise chloroplast genome of Nelumbo nucifera, (Nelumbonaceae) evaluated with Sanger, Illumina MiSeq, and PacBio RS II sequencing platforms: insight into the plastid evolution of basal eudicots. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nashima K, et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of pineapple (Ananas comosus) Tree Genet. Genomes. 2015;11:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11295-015-0892-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bodin SS, Kim JS, Kim JH. Complete chloroplast genome of Chionographis japonica (willd.) maxim. (Melanthiaceae): comparative genomics and evaluation of universal primers for liliales. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013;31:1407–1421. doi: 10.1007/s11105-013-0616-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin G, Baurens FC, Aury JM, D’Hont A. The complete chloroplast genome of banana (Musa acuminata, zingiberales): insight into plastid monocotyledon evolution. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim KJ, Lee HL. Complete chloroplast genome sequences from korean ginseng (Panax schinseng Nees) and comparative analysis of sequence evolution among 17 vascular plants. DNA Res. 2004;11:247–261. doi: 10.1093/dnares/11.4.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clegg MT, Gaut BS, Learn GHJ, Morton BR. Rates and patterns of chloroplast DNA evolution. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:6795–6801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morton BR, Clegg MT. Neighboring base composition in strongly correlated with base substitution in a region of the chloroplast genome. J. Mol. Evol. 1995;41:597–603. doi: 10.1007/BF00175818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katayama H, Uematsu C. Structural analysis of chloroplast DNA in Prunus (Rosaceae): evolution, genetic diversity and unequal mutations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005;111:1430–1439. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xi Z, et al. Phylogenomics and a posteriori data partitioning resolve the Cretaceous angiosperm radiation Malpighiales. P. Natl. Acad. Sci.USA. 2012;109:17519–17524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205818109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jansen RK, et al. Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relationships in angiosperms and identifies genome-scale evolutionary patterns. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;104:19369–19374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709121104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Group TAP. An update of the angiosperm phylogeny group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2016;181:1–20. doi: 10.1111/boj.12385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soltis DE, Kuzoff RK. Discordance between nuclear and chloroplast phylogenies in the Heuchera group (Saxifragaceae) Evolution. 1995;49:727–742. doi: 10.2307/2410326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu WB, Huang PH, Li DZ, Wang H. Incongruence between nuclear and chloroplast DNA phylogenies in Pedicularis section Cyathophora (Orobanchaceae) PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e74828. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hall BG. Comparison of the accuracies of several phylogenetic methods using protein and DNA sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005;22:792–802. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roberts RJ, Carneiro MO, Schatz MC. The advantages of SMRT sequencing. Genome biol. 2013;14:405. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-6-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chin CS, et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat. methods. 2013;10:563–569. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Myers EW, et al. “A whole-genome assembly of Drosophila”. Science. 2000;5461:2196–2204. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taylor, D. L. PHAST (Phage Assembly Suite and Tutorial): A Web-based Genome Assembly Teaching Tool. Davidson College (2012).

- 51.Hyatt D, et al. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Conant GC, Wolfe KH. GenomeVx: simple web-based creation of editable circular chromosome maps. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:861–862. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mayor C, et al. VISTA: visualizing global DNA sequence alignments of arbitrary length. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:1046–1047. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.11.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kurtz S, et al. REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4633–4642. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thiel T, et al. Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of gene derived SSR-markers in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Theor. Appl. Genet. 2003;106:411–422. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swofford, D. L. PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods), Version 4.0 (2003).

- 59.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. Fasttree 2 – approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE. 2012;5:e9490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guisinger MM, Kuehl JV, Boore JL, Jansen RK. Extreme reconfiguration of plastid genomes in the angiosperm family Geraniaceae: rearrangements, repeats, and codon usage. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28:583–600. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.