Abstract

Background

Limitation in function is a primary reason people with low back pain seek medical treatment. Specific lumbar movement patterns, repeated throughout the day, have been proposed to contribute to the development and course of low back pain. Varying the demands of a functional activity test may provide some insight into whether people display consistent lumbar movement patterns during functional activities. Our purpose was to examine the consistency of the lumbar movement pattern during variations of a functional activity test in people with low back pain and back-healthy people.

Methods

16 back-healthy adults and 32 people with low back pain participated. Low back pain participants were classified based on the level of self-reported functional limitations. Participants performed 5 different conditions of a functional activity test. Lumbar excursion in the early phase of movement was examined. The association between functional limitations and early phase lumbar excursion for each test condition was examined.

Findings

People with low back pain and high levels of functional limitation demonstrated a consistent pattern of greater early phase lumbar excursion across test conditions (p<.05). For each test condition, the amount of early phase lumbar excursion was associated with functional limitation (r=0.28–0.62)

Interpretation

Our research provides preliminary evidence that people with low back pain adopt consistent movement patterns during the performance of functional activities. Our findings indicate that the lumbar spine consistently moves more readily into its available range in people with low back pain and high levels of functional limitation. How the lumbar spine moves during a functional activity may contribute to functional limitations.

Keywords: Low back pain, movement, functional activity, functional limitation

1. Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is a highly prevalent musculoskeletal pain condition that affects up to 80% of the population at some point in their lifetime.(Lawrence et al., 1989) Limitation in the performance of daily activities is a primary reason people seek initial(Mortimer et al., 2003) and repeat medical care for LBP.(McPhillips-Tangum et al., 1998) Since the performance of daily functional activities is such an important component of why people with LBP seek care, it seems imperative to examine how people with LBP perform their functional activities. Examination of the lumbar movement pattern during functional activities may provide insight into processes that may be contributing to the development and course of the LBP condition.

The Kinesiopathological (KP) model is a conceptual model that provides a framework for understanding how movements and postures used during functional activities may contribute to the development and course of musculoskeletal pain conditions.(Sahrmann, 2002) An assumption of the model is that musculoskeletal pain conditions develop as a result of the use of direction-specific patterns of movements and postures repeated throughout the day. In the case of LBP, it is proposed that people adopt a movement pattern during performance of functional activities in which the lumbar spine moves more readily into its available range than other joints that can contribute to the desired movement.(Gombatto et al., 2007; Sahrmann, 2002; Scholtes et al., 2009; Scholtes et al., 2010; Van Dillen et al., 2007) Over time, the repetition of the same lumbar movement pattern across a range of everyday activities can lead to an accumulation of stress in the lumbar tissues, LBP symptoms, and eventually micro- and macro- level tissue injury.(Adams, 2013; McGill, 1997)

In prior research, aspects of the lumbar movement pattern have been indexed using several different variables, including the onset and timing of movement of the lumbar spine relative to other joints,(Scholtes et al., 2009; Scholtes et al., 2010; Van Dillen et al., 2007) and the amount of lumbar excursion in a specific movement direction (Hoffman et al., 2012; Marich et al., 2015; Scholtes et al., 2009; Scholtes et al., 2010) during standardized clinical tests such as forward bending in standing.(Esola et al., 1996; McGregor et al., 1997) Differences have been reported between subgroups of people with LBP (Gombatto et al., 2007; Van Dillen et al., 2007) as well as between back-healthy (BH) people and people with LBP.(Scholtes et al., 2009; Scholtes et al., 2010; Weyrauch et al., 2015) Overall the findings from these studies indicate that people with LBP move the lumbar spine more readily than other joints. Recent data indicates that the lumbar movement pattern observed during the forward trunk flexion phase of the clinical test of forward bending is similar to the lumbar movement pattern used during the reaching phase of the functional activity test of picking up an object (PUO).(Marich et al., 2015) In the PUO test, people with LBP and high levels of functional limitation displayed greater lumbar excursion in the early phase of movement during the reaching phase compared to BH people and people with low levels of functional limitations. In addition, the amount of lumbar excursion in the early phase was associated with functional limitations. Since most functional activities are performed in the early- to mid-ranges of lumbar motion, (Bible et al., 2010; Cobian et al., 2013; Rose and Gamble, 2006) the amount of lumbar excursion during the early phase of movement appears to be an important factor that may contribute to the functional limitations associated with LBP.

A second assumption of the KP model is that the lumbar movement pattern is used consistently across a range of functional activities.(Sahrmann, 2002) While people with LBP have been shown to display consistency in various aspects of the lumbar movement pattern when they perform a series of different clinical tests,(Sahrmann, 2002; Van Dillen et al., 1998; Van Dillen et al., 2003) to our knowledge, this has not been examined systematically during the performance of functional activities. A key first test of this assumption is to vary the demands of a single functional activity and examine an aspect of the lumbar movement pattern across the variations.

The primary purpose of the current study was to examine an aspect of the lumbar movement pattern in people with LBP and BH people when conditions of a functional activity test were varied. We hypothesized that across all conditions, people with LBP and high levels of LBP-related functional limitation would consistently display greater lumbar excursion in the early phase of the reaching movement compared to BH people and people with LBP and low levels of LBP-related functional limitation. A second purpose of the study was to examine the relationship between the movement pattern during each test condition and LBP-related functional limitation. We hypothesized that the amount of lumbar excursion in the early phase of the reaching movement during each test condition would be related to a person’s LBP-related functional limitation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Thirty-two people with LBP, and 16 gender-, age-, height- and weight-matched BH people participated. Inclusion criteria included aged 18 to 60 with a body mass index (BMI) ≤ 30 kg/m2. LBP inclusion criteria included a duration of LBP symptoms for a minimum of 12 months and LBP symptoms present on greater than ½ the days of the year.(Vonkorff, 1994) A history of LBP was defined as LBP that resulted in (1) three or more consecutive days of altered daily activities, or work or school absence, or (2) seeking some type of health intervention (e.g., physical therapist, physician, chiropractor). BH participants were excluded if they reported a history of LBP as defined. Additional participant exclusion criteria included a history of (1) numbness or tingling below the knee, (2) previous spinal surgery, (3) spinal trauma, or (4) a specific LBP diagnosis such as scoliosis or spondylolisthesis. LBP participants with a modified Oswestry Disability Index (mODI)(Fritz and Irrgang, 2001) score < 20% were considered to have low-functional limitation and were classified as LBP-Low. Participants with mODI scores 20% or greater were considered to have moderate- to high-functional limitation and were classified as LBP-High.(Fairbank et al., 1980) All participants provided written informed consent approved by the Human Research Protection Office of Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine prior to participating in the study.

2.2. Clinical Measures

All participants completed a series of self-report measures including (1) a demographic questionnaire, and (2) the Short-Form 36 Health Survey.(Ware and Sherbourne, 1992) LBP participants also completed (1) a LBP history questionnaire, (2) the numeric pain rating scale (NRS),(Downie et al., 1978; Farrar et al., 2001) (3) the mODI, and (4) the Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ).(Waddell et al., 1993)

2.3. Laboratory Measures

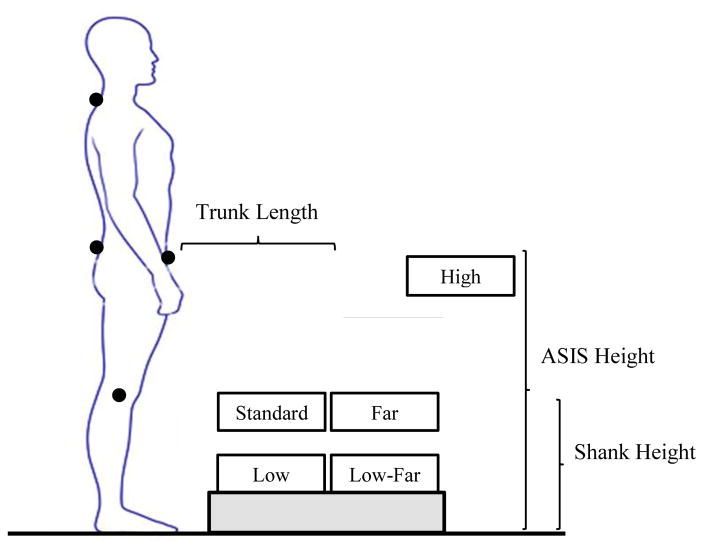

Retroreflective markers were placed on predetermined landmarks of the trunk, pelvis and lower extremities (Table 1), and kinematic data were collected using an 8-camera, 3-dimensional motion capture system (Vicon Motion Systems, LTD, Denver, CO) with a sampling rate of 120Hz. Anthropometric measurements were obtained of each participant’s shank and trunk length, and anterior superior iliac crest (ASIS) height. Shank length was measured as the vertical distance from the floor to lateral knee joint line. Trunk length was measured as the vertical distance between the spinous process of the 7th cervical (C7) and the 1st sacral (S1) vertebrae. ASIS height was measured as the vertical distance from the floor to the ASIS. Participants performed five separate conditions of the functional activity test of Pick Up an Object (PUO)(Marich et al., 2015) presented in random order (Figure 1). The standard PUO test condition involved placing a 20 x 36 x 12 cm, lightweight, container on a surface so that the top of the container was at a height equal to the participant’s shank length and a distance equal to 50% of the participant’s trunk length (Standard). To vary the demands of the PUO test, four additional test conditions were performed with the container placed on a surface so that the top of the object was at specific heights and distances scaled to the person’s anthropometrics (High, Far, Low, Low-Far; Figure 1). For each condition, the participant began the movement from a comfortable standing position with feet pelvis-width apart. The participant was instructed to reach for, and pick up the container with both hands, and return to the starting position. Participants were given a maximum of 10 seconds to complete each movement trial, and 3 separate trials were performed for each PUO test condition.

TABLE 1.

Locations of retroreflective markers.

| Marker | Location Details |

|---|---|

| Acromion* | Center of acromion |

| Manubrium | Superior aspect of manubrium |

| C7† | Spinous process 7th cervical vertebrae |

| T6† | ½ distance from C7 to T12 |

| T12† | Spinous process 12th thoracic vertebrae |

| L1 | Spinous process 1st lumbar vertebrae |

| L3† | Spinous process 3rd lumbar vertebrae |

| L5 | Spinous process 5th lumbar vertebrae |

| S1 | ½ distance measured from L5 to S2 |

| Iliac Crest* | Most superior aspect of iliac crest |

| PSIS* | Most superior aspect of posterior superior iliac spine |

| Sacrum | Distal aspect of sacrum |

| ASIS* | Most prominent aspect of anterior superior iliac spine |

| Greater Trochanter* | Most superior aspect of greater trochanter |

| Thigh* | 4-marker plate lateral distal aspect of thigh |

| Shank* | 4-marker plate lateral distal aspect of shank |

| Knee* | Lateral and medial aspect of knee joint line |

| Ankle* | Prominent bony aspect of the lateral and medial malleoli |

Indicates markers were placed bilaterally

Indicates markers were placed along the spinous process as well as at 4cm lateral to the spinous process

FIGURE 1.

Locations of object placement for the five different conditions of the Pick Up an Object (PUO) test. The object for the High condition was placed on a surface so that the top of the object was at a height equal to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and a distance equal to 150% of the trunk length. The object for the Standard condition was placed on a surface so that the top of the object was at a height equal to the shank length and a distance equal to 50% of the trunk length. The object for the Far condition was placed was placed on a surface so that the top of the object was at a height equal to the shank length and a distance equal to 100% of the trunk length. The object for the Low condition was placed on a surface so that the top of the object was at a height equal to 50% of the shank length and a distance equal to 50% of the trunk length. The object for the Low-Far was placed a was placed on a surface so that the top of the object was at a height equal to 50% of the shank length and a distance equal to 100% of the trunk length.

2.4. Data Processing

Kinematic data were processed using Visual 3D software (C-motion, Inc., Germantown, MD), and custom programs written in MATLAB software (MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA). Kinematic data were filtered using a 4th-order, dual-pass Butterworth filter with a cut-off frequency of 3 Hz.

The thoracic spine segment was defined by a vector from the C7 to the T12 spinous process. The lumbar spine segment was defined by a vector from the T12 to the S1 spinous process. The pelvis segment consisted of markers placed superficial to the right and left (a) ASIS, (b) posterior superior iliac spine, (c) iliac crests, and the distal aspect of the sacrum. The thigh segment was defined by a marker located superficial to the superior aspect of the greater trochanter, mid-thigh, and medial and lateral knee joint line.

Angular displacement in the sagittal plane was calculated across time for the thoracic, lumbar, and hip segments. Thoracic excursion was calculated as the displacement of the thoracic segment relative to the lumbar segment. Lumbar excursion was calculated as the displacement of the lumbar segment relative to the pelvis segment. Hip excursion was calculated as the displacement of the pelvis segment relative to the thigh segment. Trunk excursion was calculated as the combined excursion of the thoracic, lumbar, and hip segments. For each PUO trial, movement time (MT) was calculated as the time between the start of the forward trunk flexion and the point of maximal forward trunk flexion. The start of the forward trunk flexion was defined as a 1° change in trunk excursion from the initial standing position, and the stop of the forward trunk flexion was defined as the point equal to 98% of the maximal trunk flexion. Lumbar lordosis angle was calculated in a static standing position.(Norton et al., 2004; Sorensen et al., 2015)

2.5. Dependent Variables

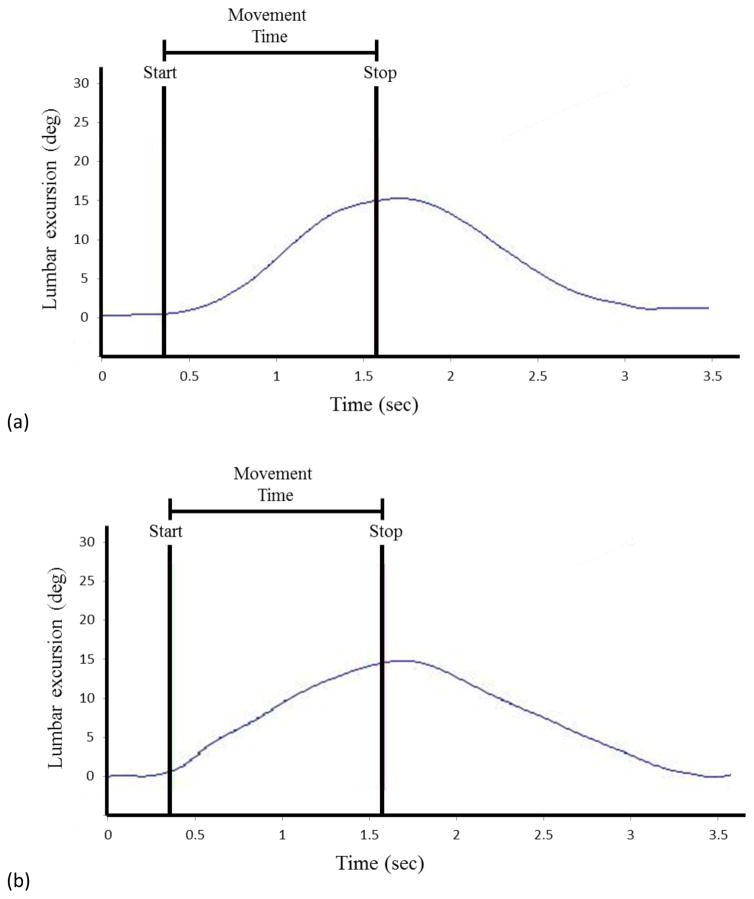

Kinematics of the lumbar segment were examined during the reaching phase of each PUO trial from the start of motion to the stop of motion. Maximal excursion of the lumbar segment was calculated as well as excursions of the lumbar segment for the early phase (0–50% of MT) and late phase (50–100% of MT) of movement. An example of the kinematic output from the lumbar segment is presented in Figure 2. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), and the standard error of the measure (SEM) were calculated for maximum and early phase lumbar excursion for the Standard test condition using the 16 BH participants from this study. The ICC [3,1] values ranged from 0.89–0.97, and the SEM values ranged from 0.8° to 1.2°.

FIGURE 2.

Time series data for lumbar spine excursion during the Pick Up an Object–Standard condition for (a) a typical back-healthy participant, and (b) a typical low back pain participant. The start of the forward trunk flexion and the maximal trunk flexion (stop) are indicated by the vertical lines. The start of the forward trunk flexion was identified as a 1° change in trunk excursion, and the stop of the forward trunk flexion was identified as the point equal to 98% of the maximal trunk flexion. The time between the start and stop of the forward motion is the movement time.

The sample size of 48 participants (16 per group) was based on an η2(partial) effect size of 0.24 from a prior study that examined lumbar kinematics during a clinical test and a functional activity test.(Marich et al., 2015) A total of 48 participants was determined to be sufficient to detect an interaction effect of group and test condition with a two-tailed α ≤ .05 and power of 0.80.

2.6. Data Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM® SPSS® Statistics Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and were two-tailed tests with the significance level set at p ≤ .05. A chi-square test was used to test for differences in gender distribution. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to test for differences in participant age, height, weight, and BMI. One-way ANOVA tests also were used to test for differences in lumbar lordosis angle, maximal trunk excursion, and MT for each test condition. Independent groups t-tests were used to test for differences in LBP-related characteristics between the two LBP groups. A repeated measures ANOVA test was conducted to test for the main and interaction effects of group (BH, LBP-Low, LBP-High) and test condition (High, Standard, Far, Low, Low-Far) for lumbar excursion in the early phase of MT. The Fisher’s least significant difference post-hoc test was performed when a significant interaction was obtained. Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were calculated to index the association between lumbar excursion in the early phase of the reaching movement for each test condition and mODI score.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

The groups did not differ in age, gender, height, weight, or BMI (Table 2). Compared to the LBP-Low group, the LBP-High group had a significantly greater (1) mODI (p<.01), (2) FABQ-work (p=.01), (3) FABQ-physical activity (p=.01), and (4) NRS average pain rating (p=.03) score. There were no differences among the groups for lumbar curvature angle in standing, or maximal trunk excursion or MT for any of the PUO test conditions (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Means (SD) for baseline descriptive statistics for all participants.

| Characteristic | Back- healthy (n = 16) | LBP-Low (n =16) | LBP-High (n = 16) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | ||||

| Female, n (%) | 10 (63) | 10 (63) | 10 (63) | 1.0 |

| Age, y | 37.4 (11.0) | 38.6 (13.0) | 36.2 (11.1) | .84 |

| Height, m | 1.70 (.13) | 1.71 (.11) | 1.71 (.09) | .85 |

| Weight, kg | 68.6 (14.6) | 68.9 (15.6) | 71.6 (9.6) | .79 |

| BMI*, kg/m2 | 23.6 (2.4) | 23.3 (3.3) | 24.2 (2.3) | .60 |

| Low back pain | ||||

| mODI†, % | 12.0 (4.4) | 33.8 (8.7) | <.01 | |

| Low back pain duration, y | 10.9 (7.6) | 14.5 (6.8) | .17 | |

| FABQ-Physical Activity subscale‡ | 5.4 (6.9) | 12.6 (8.5) | .01 | |

| FABQ-Work subscale‡ | 9.8 (4.7) | 14.7 (5.6) | .01 | |

| Pain intensity || | ||||

| Current | 2.9 (1.1) | 3.2 (0.8) | .37 | |

| Average (prior 7 days) | 3.1 (0.8) | 3.6 (0.6) | .03 | |

| Worst (prior 7 days) | 5.3 (1.2) | 5.6 (1.1) | .37 | |

Bold font indicates significance at p ≤ .05

Body mass index

modified Oswestry Disability Index; scores range from 0–100%

Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire; scores range from 0–24 for the physical activity subscale, and 0–42 for the work subscale

Scores range from 0 ("no pain") to 10 ("worst pain imaginable")

TABLE 3.

Means (SD) for lumbar curvature angle in standing, and maximal trunk flexion and movement time for each condition of the functional activity test for the back-healthy group, low back pain group with < 20% modified Oswestry Disability Index score (LBP-Low), and the low back pain group with ≥20% modified Oswestry Disability Index score (LBP-High).

| Characteristic | Back-healthy (n = 16) | LBP-Low (n =16) | LBP-High (n = 16) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumbar curvature, deg | 159.2 (7.9) | 158.2 (6.6) | 162.1 (5.4) | .53 |

| Maximal trunk flexion, deg | ||||

| High | 47.6 (9.1) | 47.8 (11.4) | 51.2 (12.7) | .58 |

| Standard | 89.5 (8.4) | 90.0 (9.8) | 88.6 (10.9) | .91 |

| Far | 97.9 (8.6) | 96.0 (10.2) | 94.7 (13.5) | .69 |

| Low | 119.7 (12.5) | 122.3 (12.9) | 119.5 (14.9) | .81 |

| Low-Far | 124.0 (14.7) | 126.5 (12.2) | 123.8 (15.2) | .84 |

| Movement time, sec | ||||

| High | 1.02 (.16) | 1.12 (.23) | 1.07 (.20) | .41 |

| Standard | 1.15 (.22) | 1.25 (.35) | 1.24 (.27) | .60 |

| Far | 1.18 (.25) | 1.25 (.38) | 1.21 (24) | .78 |

| Low | 1.33 (.29) | 1.40 (.42) | 1.39 (.31) | .84 |

| Low-Far | 1.29 (.23) | 1.34 (.39) | 1.33 (.20) | .90 |

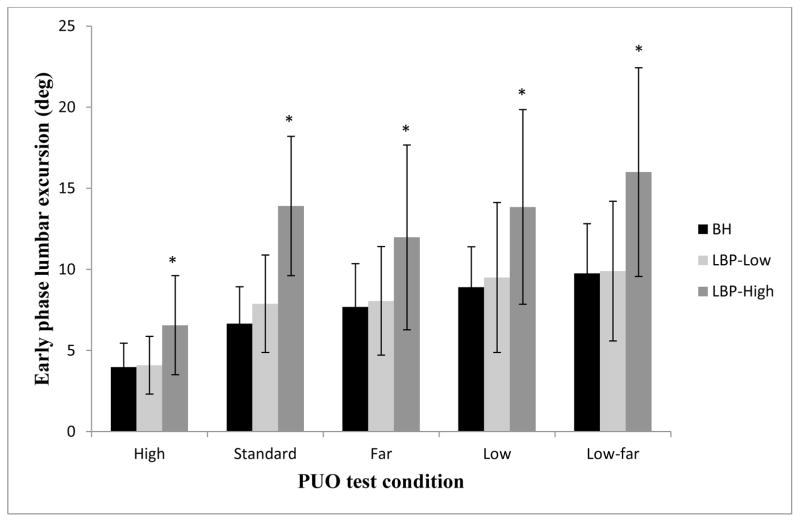

3.2. Movement pattern consistency

There was a significant interaction of condition and group (F(4.29, 96.54)=5.92, p<.01) for the amount of lumbar excursion in the early phase of movement. Figure 3 illustrates the results of the post-hoc tests indicating that, compared to the BH and LBP-Low groups, the LBP-High group displayed greater lumbar excursion in the early phase of movement for all PUO test conditions (p<.05), and the BH and LBP-Low groups did not differ for any PUO test condition (p>.05). Because FABQ subscale scores and NRS-Average scores were different for the LBP groups, we conducted separate repeated measures ANOVA tests, and obtained similar results when controlling for FABQ-PA (F(2.8,81.9)=4.94, p<.01 ), FABQ-W (F(2.8,81.6)=5.02, p<.01), and NRS-Average (F(2.8,80.1)=3.23, p<.05).

FIGURE 3.

Lumbar excursion (mean, SD) for the early phase (0–50% of movement time) of the reaching movement for each condition of the Pick Up an Object (PUO) test for the back-healthy (BH), low back pain group with < 20% modified Oswestry Disability Index score (LBP-Low), and the low back pain group with ≥20% modified Oswestry Disability Index score (LBP-High).

*Indicates significant difference between the LBP-High group and both the BH and LBP-Low group

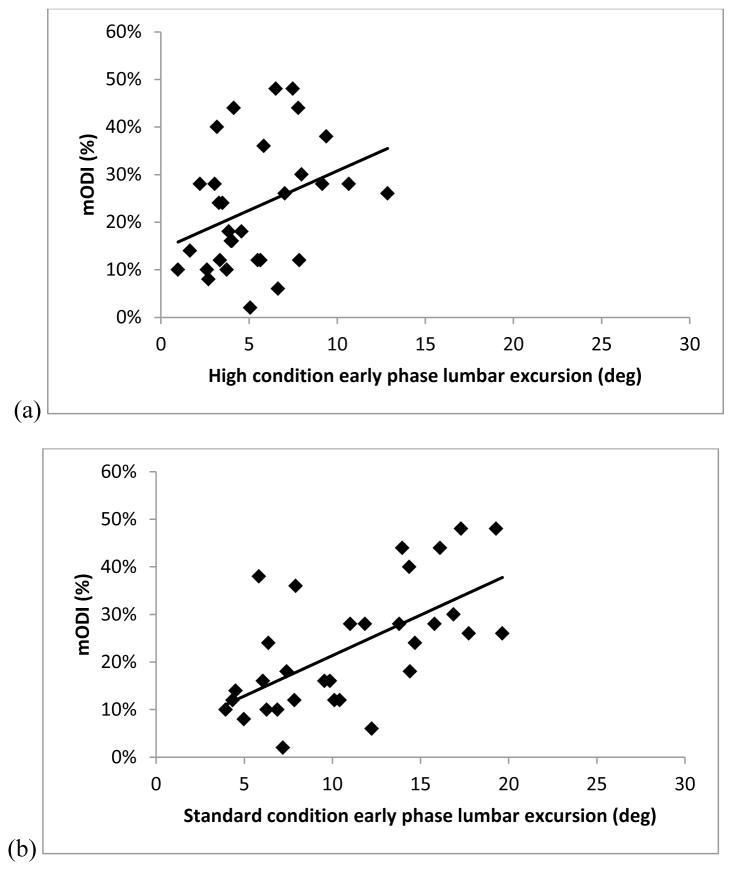

3.3. Association between lumbar excursion and functional limitation

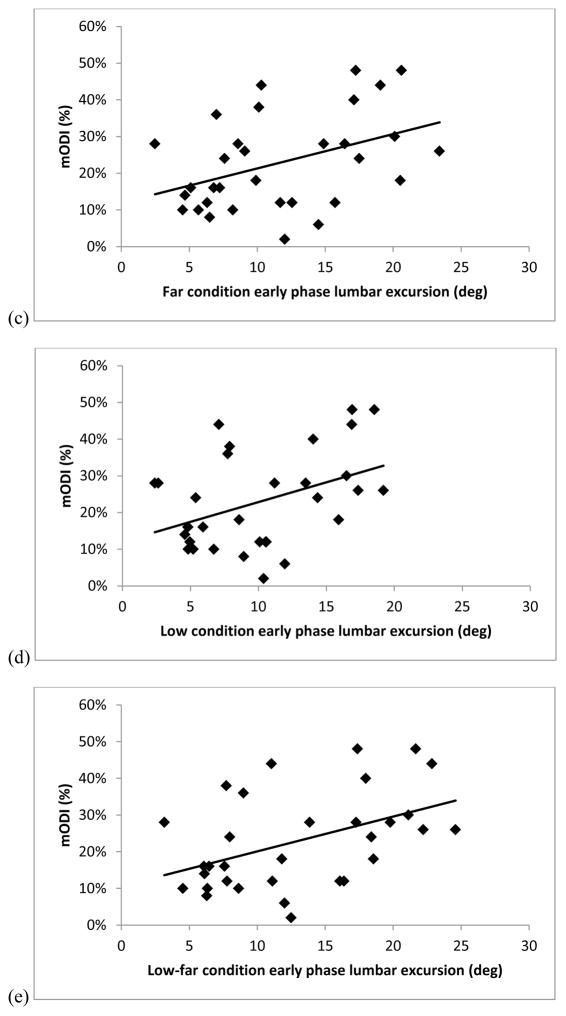

Figure 4 illustrates that there were significant associations between mODI and lumbar excursion in the early phase of movement for the Standard (r=0.62, r2=0.39, p<.01), Far (r=0.42, r2=0.17, p=.02), Low (r=0.41, r2=0.17, p=.02), and Low-Far (r=0.46, r2=0.21, p=.01) conditions. The association between mODI and lumbar excursion in the early phase of MT was not significant for the High condition (r=0.28, r2=0.12., p=.13).

FIGURE 4.

Scatterplots of the association between modified Oswestry Disability Index (mODI) scores (0-100%) and the early phase (0–50% of movement time) lumbar excursion (in degrees) during the reaching movement for people with low back pain for the (a) High (r=0.28, r2=0.12., p=.13) , (b) Standard (r=0.62, r2=0.39, p<.01), (c) Far (r=0.42, r2=0.17, p=.02), (d) Low (r=0.41, r2=0.17, p=.02), and (e) Low-far (r=0.46, r2=0.21, p=.01) conditions.

4. Discussion

In examining the consistency of the lumbar movement pattern, we found people with LBP and high levels of functional limitation consistently displayed greater lumbar excursion in the early phase of movement compared to those with LBP and low levels of functional limitation and BH people. These results could not be explained by additional factors such as lumbar curvature, FABQ, or symptom intensity. Further, as hypothesized, greater lumbar excursion in the early phase of the movement was consistently associated with LBP-related functional limitation. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that people display consistencies in an aspect of the lumbar movement pattern across variations of a functional activity test, and the movement pattern is related to LBP-related functional limitations.

Although several studies have examined lumbar kinematics during a single functional activity test,(Alqhtani et al., 2015; Shum et al., 2005a, b, 2007) very little has been reported on the consistency of aspects of the lumbar movement pattern across multiple functional activity tests. Marras et al. reported people with LBP displayed increased cumulative spinal loading compared to BH people during a lifting task from varying heights and distances.(Marras et al., 2001) Thomas et al. reported BH people displayed consistent patterns of spine-hip ratios when the target locations of a reaching test were varied.(Thomas et al., 1998; Thomas and Gibson, 2007) Different from the Thomas studies, we included people with LBP with varying levels of LBP-related functional limitation, and we analyzed lumbar excursion rather than a hip-spine ratio. Our findings indicate that the lumbar spine consistently moves more readily into its available range in the reaching phase of the PUO task in people with LBP and high levels of functional limitation. Because the majority of daily functional activities are performed in the early- to mid-ranges of motion,(Bible et al., 2010; Cobian et al., 2013; Rose and Gamble, 2006) the movement pattern may be a key factor contributing to concentrated tissue stress and potentially to LBP symptoms and functional limitation.(Adams, 2013; McGill, 1997; Sahrmann, 2002)

Other studies have reported associations ranging from r=0.09–0.73 when examining functional limitation and maximal lumbar excursion during a clinical test.(Gronblad et al., 1997; Nattrass et al., 1999; Sullivan et al., 2000; Waddell et al., 1992) We found moderate to large(Cohen, 1988) associations between a person’s mODI score and the amount of lumbar excursion in the early phase of the reaching movement for 4 of the 5 test conditions. Our findings are consistent with a previous study that found a significant, moderate-size association between mODI and early phase lumbar excursion in the reaching movement during the PUO test.(Marich et al., 2015) Thus, the current findings suggest that the manner in which a person moves the lumbar spine during a functional activity may contribute to the functional limitations. These findings are important because functional limitations are often the reason people with LBP seek treatment.(McPhillips-Tangum et al., 1998; Mortimer et al., 2003)

While our study examined variations of a single functional activity, the results provide some initial support for the proposal that people with LBP use a consistent lumbar movement pattern across a range of functional activities. Therapeutically, repeated movement during exercise is known to induce adaptations in the musculoskeletal and nervous systems.(Adkins et al., 2006; Karni et al., 1995; Kent et al., 2015; Sahrmann, 2002; Tsao et al., 2010; Tsao and Hodges, 2007, 2008) It could be argued that similar biological adaptations may be occurring due to repetition of movements during everyday activities, resulting in the altered movement pattern displayed by people with LBP and high levels of functional limitation. Additionally, the altered movement pattern displayed during functional activities is associated with their LBP-related limitations. A primary reason people with LBP seek care is limitations in performance of daily activities.(McPhillips-Tangum et al., 1998; Mortimer et al., 2003) Thus, one logical approach to treatment would be to provide challenging, repetitive practice in which the person learns to modify the altered movement pattern within the context of performing his functional activities.

One limitation of the current study is that the standardized set-up and verbal instructions of the functional activity test may not represent the actual circumstances a person encounters during the day. Specifically, the object was placed at a location that was scaled to the individual’s anthropometrics, rather than at the same height and distance for all participants. The scaling was done, however, to eliminate participant height as a confound. A second limitation is that we examined the kinematics only during the reaching phase of the functional activity. Additional analyses should be conducted to examine aspects of the lumbar movement pattern during the return to standing phase of the functional activity. A third limitation is that the test conditions were all variations of a single activity performed in the sagittal plane. Thus, it is unknown whether people would demonstrate similar consistency in their lumbar movement pattern with activities that require movement in multiple planes.

Highlights.

Lumbar kinematics during variations of a functional activity test were examined.

People with LBP and high limitations consistently showed greater early phase lumbar excursion.

Early phase lumbar excursion was associated with functional limitations.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of Sara Putnam, who assisted with the study design, data collection, and data processing. We would also like to acknowledge members of the Musculoskeletal Analysis Laboratory for their assistance with recruitment, planning, and data processing. This work was partially funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research grant R01 HD047709, the Foundation for Physical Therapy; Promotion of Doctoral Studies Scholarship, the Dr. Hans and Clara Davis Zimmerman Foundation, and the Program in Physical Therapy at Washington University School of Medicine.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams MA. The biomechanics of back pain. 3. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; Edinburgh ; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Adkins DL, Boychuk J, Remple MS, Kleim JA. Motor training induces experience-specific patterns of plasticity across motor cortex and spinal cord. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2006;101:1776–1782. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00515.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alqhtani RS, Jones MD, Theobald PS, Williams JM. Correlation of lumbar-hip kinematics between trunk flexion and other functional tasks. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 2015;38:442–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bible JE, Biswas D, Miller CP, Whang PG, Grauer JN. Normal Functional Range of Motion of the Lumbar Spine During 15 Activities of Daily Living. Journal of Spinal Disorders & Techniques. 2010;23:106–112. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e3181981823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobian DG, Daehn NS, Anderson PA, Heiderscheit BC. Active Cervical and Lumbar Range of Motion During Performance of Activities of Daily Living in Healthy Young Adults. Spine. 2013;38:1754–1763. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182a2119c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Downie WW, Leatham PA, Rhind VM, Wright V, Branco JA, Anderson JA. Studies with pain rating-scales. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 1978;37:378–381. doi: 10.1136/ard.37.4.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esola MA, McClure PW, Fitzgerald GK, Siegler S. Analysis of lumbar spine and hip motion during forward bending in subjects with and without a history of low back pain. Spine. 1996;21:71–78. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199601010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, O'Brien JP. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980;66:271–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar JT, Young JP, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94:149–158. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ. A comparison of a modified Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire and the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale. Physical Therapy. 2001;81:776–788. doi: 10.1093/ptj/81.2.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gombatto SP, Collins DR, Sahrmann SA, Engsberg JR, Van Dillen LR. Patterns of lumbar region movement during trunk lateral bending in 2 subgroups of people with low back pain. Physical Therapy. 2007;87:441–454. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20050370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronblad M, Hurri H, Kouri JP. Relationships between spinal mobility, physical performance tests, pain intensity and disability assessments in chronic low back pain patients. Scandinavian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 1997;29:17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman SL, Johnson MB, Zou DQ, Van Dillen LR. Differences in end-range lumbar flexion during slumped sitting and forward bending between low back pain subgroups and genders. Manual Therapy. 2012;17:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karni A, Meyer G, Jezzard P, Adams MM, Turner R, Ungerleider LG. Functional MRI evidence for adult motor cortex plasticity during motor skill learning. Nature. 1995;377:155–158. doi: 10.1038/377155a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent P, Laird R, Haines T. The effect of changing movement and posture using motion-sensor biofeedback, versus guidelines-based care, on the clinical outcomes of people with sub-acute or chronic low back pain-a multicentre, cluster-randomised, placebo-controlled, pilot trial. Bmc Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2015:16. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0591-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence RC, Hochberg MC, Kelsey JL, McDuffie FC, Medsger TA, Felts WR, Shulman LE. Estimates of the prevalence of selected arthritic and musculoskeletal diseases in the United States. Journal of Rheumatology. 1989;16:427–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marich AV, Bohall SC, Hwang CT, Sorensen CJ, Van Dillen LR. Lumbar movement pattern during a clinical test and a functional activity test in people with and people without low back pain. American Society of Biomechanics 39th Annual Meeting.2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marras WS, Davis KG, Ferguson SA, Lucas BR, Gupta P. Spine loading characteristics of patients with low back pain compared with asymptomatic individuals. Spine. 2001;26:2566–2574. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200112010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill SM. The biomechanics of low back injury: Implications on current practice in industry and the clinic. Journal of Biomechanics. 1997;30:465–475. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(96)00172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor AH, McCarthy ID, Dore CJ, Hughes SP. Quantitative assessment of the motion of the lumbar spine in the low back pain population and the effect of different spinal pathologies of this motion. European Spine Journal. 1997;6:308–315. doi: 10.1007/BF01142676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhillips-Tangum CA, Cherkin DC, Rhodes LA, Markham C. Reasons for repeated medical visits among patients with chronic back pain. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1998;13:289–295. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00093.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer M, Ahlberg G grp M.U.-N.s. To seek or not to seek? Care-seeking behaviour among people with low-back pain. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2003;31:194–203. doi: 10.1080/14034940210134086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattrass CL, Nitschke JE, Disler PB, Chou MJ, Ooi KT. Lumbar spine range of motion as a measure of physical and functional impairment: an investigation of validity. Clinical Rehabilitation. 1999;13:211–218. doi: 10.1177/026921559901300305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton BJ, Sahrmann SA, Van Dillen LR. Differences in measurements of lumbar curvature related to gender and low back pain. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2004;34:524–534. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2004.34.9.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose J, Gamble JG. Human Walking. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sahrmann S. Diagnosis and treatment of movement impairment syndromes. Mosby; St. Louis, Mo: 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholtes SA, Gornbatto SP, Van Dillen LR. Differences in lumbopelvic motion between people with and people without low back pain during two lower limb movement tests. Clinical Biomechanics. 2009;24:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholtes SA, Norton BJ, Lang CE, Van Dillen LR. The effect of within-session instruction on lumbopelvic motion during a lower limb movement in people with and people without low back pain. Manual Therapy. 2010;15:496–501. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shum GLK, Crosbie J, Lee RYW. Effect of low back pain on the kinematics and joint coordination of the lumbar spine and hip during sit-to-stand and stand-to-sit. Spine. 2005a;30:1998–2004. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000176195.16128.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shum GLK, Crosbie J, Lee RYW. Symptomatic and asymptomatic movement coordination of the lumbar spine and hip during an everyday activity. Spine. 2005b;30:E697–E702. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000188255.10759.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shum GLK, Crosbie J, Lee RYW. Movement coordination of the lumbar spine and hip during a picking up activity in low back pain subjects. European Spine Journal. 2007;16:749–758. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0122-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen CJ, Norton BJ, Callaghan JP, Hwang CT, Van Dillen LR. Is lumbar lordosis related to low back pain development during prolonged standing? Manual Therapy. 2015;20:553–557. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MS, Shoaf LD, Riddle DL. The relationship of lumbar flexion to disability in patients with low back pain. Physical Therapy. 2000;80:240–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JS, Corcos DM, Hasan Z. The influence of gender on spine, hip, knee, and ankle motions during a reaching task. Journal of Motor Behavior. 1998;30:98–103. doi: 10.1080/00222899809601327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JS, Gibson GE. Coordination and timing of spine and hip joints during full body reaching tasks. Human Movement Science. 2007;26:124–140. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao H, Galea MP, Hodges PW. Driving plasticity in the motor cortex in recurrent low back pain. European Journal of Pain. 2010;14:832–839. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao H, Hodges PW. Immediate changes in feedforward postural adjustments following voluntary motor training. Experimental Brain Research. 2007;181:537–546. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-0950-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao H, Hodges PW. Persistence of improvements in postural strategies following motor control training in people with recurrent low back pain. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 2008;18:559–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dillen LR, Gombatto SP, Collins DR, Engsberg JR, Sahrmann SA. Symmetry of timing of hip and lumbopelvic rotation motion in 2 different subgroups of people with low back pain. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2007;88:351–360. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dillen LR, Sahrmann SA, Norton BJ, Caldwell CA, Fleming DA, McDonnell MK, Woolsey NB. Reliability of physical examination items used for classification of patients with low back pain. Physical Therapy. 1998;78:979–988. doi: 10.1093/ptj/78.9.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dillen LR, Sahrmann SA, Norton BJ, Caldwell CA, McDonnell MK, Bloom N. The effect of modifying patient-preferred spinal movement and alignment during symptom testing in patients with low back pain: A preliminary report. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2003;84:313–322. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2003.50010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonkorff M. Studying the natural-history of back pain. Spine. 1994;19:S2041–S2046. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199409151-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main CJ. A fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire (fabq) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low-back-pain and disability. Pain. 1993;52:157–168. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90127-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell G, Somerville D, Henderson I, Newton M. Objective clinical-evaluation of physical impairment in chronic low-back-pain. Spine. 1992;17:617–628. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199206000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36) .1. Conceptual-framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyrauch SA, Bohall SC, Sorensen CJ, Van Dillen LR. Association Between Rotation-Related Impairments and Activity Type in People With and Without Low Back Pain. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2015;96:1506–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]