ABSTRACT

Objectives:

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a clinicopathologic disorder characterized by infiltration of eosinophils into the esophagus. Primary treatment approaches include topical corticosteroids and/or food elimination. The aim of the present study was to compare the effectiveness of combination therapy (topical corticosteroid plus test-based food elimination [FS]) with single therapy (topical corticosteroid [S] or test-based food elimination [F]).

Methods:

Chart review of patients with EoE at Texas Children's Hospital (age <21 years) was performed. Clinical and histological statuses were evaluated after a 3-month treatment with either single or combination therapy. Comparisons were analyzed using Fisher exact test, Kruskal-Wallis tests, and multiple logistic regression models.

Results:

Among 670 charts, 63 patients (1–21 years, median 10.3 years) with clinicopathologic diagnoses of EoE were identified. Combination FS therapy was provided to 51% (n = 32) and single treatment (S, F) to 27% (n = 17) or 22% (n = 14) of patients, respectively. Clinical responses were noted in 91% (n = 29), 71% (n = 12), and 64% (n = 14) of patients in the FS, S, and F groups, respectively. The odds of clinically improving were 4.6 times greater (95% confidence interval: 1.1–18.8) with combination versus single therapy. The median peak number of eosinophils per high-power field after 3-month therapy was not significantly different in the S, F, and FS groups.

Conclusions:

The combination of topical corticosteroids with specific food elimination is as effective in achieving clinical and histological remissions as the single-treatment approaches. Responses were achieved with the combination in patients who had previously failed single-agent therapy. Prospective research of this combination approach in young patients with EoE is needed.

Keywords: budesonide, combination therapy, eosinophilic esophagitis, eosinophils, food allergy, immediate-type hypersensitivity testing, patch testing, test-based elimination diet, topical corticosteroids

What Is Known

Primary treatment approaches for eosinophilic esophagitis include topical corticosteroids or food elimination. These single treatment approaches are effective.

What Is New

The combination of topical corticosteroids with specific food elimination is as effective in achieving clinical and histological remissions as the single treatment approaches.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune- or antigen-mediated clinicopathologic disorder characterized by eosinophilic infiltration (≥15 eosinophils [eos]/high-power field [hpf]) (1). Among pediatric patients, the incidence of EoE is 0.7 to 10 cases per 100,000 children (2). Infants and toddlers present with feeding difficulties, whereas school-aged children generally exhibit vomiting and abdominal pain. Teenagers usually present with dysphagia, epigastric pain, and food impaction (1). Untreated EoE can progress to more serious conditions, such as dysphagia and esophageal strictures, during adulthood (3). These EoE-related conditions are associated with significant morbidity (4,5). Thus, effective and early treatment of pediatric EoE is critical for preventing long-term esophageal problems.

Primary treatment options for EoE include topical corticosteroids, food elimination, and elemental diets. High-dose topical corticosteroids (6,7) and specific elimination diets improve symptoms, reduce esophageal eosinophilic mucosal infiltrates, and improve endoscopic markers of inflammation. Allergic comorbidities occur in 42% to 93% of pediatric patients, with food allergies being the most common. An elemental diet based on an amino acid–based formula is the most effective dietary therapy for pediatric EoE, resulting in 96% histological improvement (8). High cost, poor taste, and nutritional deficiencies, however, limit the use of this treatment option. The 6-food elimination diet (SFED) with subsequent reintroduction of the offending foods and endoscopic reevaluation is extremely effective in children (9). Although 74% histological improvement occurs with this strategy, the expense of multiple upper endoscopic procedures limits its application. A selective elimination diet based on skin testing produced promising results with 75% symptomatic and histological improvement in a large pediatric series (6,10). This test-based elimination diet is based on a skin-prick test (SPT) for immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated food hypersensitivity and an atopic patch test (APT) for non-IgE–mediated delayed-food hypersensitivity (1,11). Thus, although several treatment options have been tested, limitations of individual approaches and lack of a standardized therapeutic strategy complicate the management of EoE.

There are little data available regarding the efficacy of combining topical corticosteroids with test-based food elimination to induce clinical and histological remissions in allergic patients with EoE. There are no single-center studies that have directly compared combination therapy to single-agent dietary restriction or topical corticosteroid therapy for symptom control and treatment of esophageal eosinophilia. The goal of the present study was to determine the effectiveness of a combination regimen consisting of topical corticosteroids with test-based food elimination compared to single therapies.

METHODS

Study Design

This retrospective cohort study included patients diagnosed as having EoE between January 2006 and December 2012 at the Allergy and Immunology clinic and the Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases clinic at Texas Children's Hospital. The present study was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Subjects

Subjects were recruited from the Texas Children's Hospital’ Allergy and Immunology and Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases clinics. Records were reviewed if patients met the following inclusion criteria. First, a physician diagnosed EoE1 based on the criteria of ≥15 eosinophil count per high-powered field (eos/hpf) in ≥1 esophageal biopsies. Second, the patients did not have a documented response to a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) 8 weeks before the first biopsy. All patients were on a PPI at the time of the biopsy. Analyses were performed on patients who were treated with PPI. Third, the patient was younger than 21 years. Exclusion criteria included the following: the patient did not meet the diagnostic criteria or had another diagnosis associated with gastrointestinal eosinophilia (eg, celiac disease or inflammatory bowel disease), a mitochondrial disorder, prolonged gastric emptying, lack of previous allergy evaluation of associated atopic diathesis (allergic rhinitis, asthma, hives, or atopic dermatitis), no assigned treatment regimen, received 3 treatment regimens (topical corticosteroids, test-based food elimination, or a combination of both) before reevaluation, or noncompliance documented by a physician. Detailed demographic data, including sex, age at diagnosis, presenting clinical symptoms, associated atopic diathesis (allergic rhinitis, asthma, hives or atopic dermatitis), PPI use before first biopsy, and eos/hpf in the first and repeat biopsies (if done), were obtained. Data based on the particular treatment regimen (eg, dose of corticosteroids for topical corticosteroid group or results of SPT and APT for test-based food elimination group) were obtained. Patients were considered atopic if they had physician-diagnosed asthma, allergic rhinitis, or atopic dermatitis. Treatment regimens were determined according to the preferences of the patient and physician at the time of the visit. Patients were followed for ≥3 months during treatment. A histological examination was conducted by a clinical pathologist at the time of biopsy. The pathologist was blinded to the treatment group during the histological examination.

Dietary Therapy

Test-based elimination diet was defined as the omission of foods that elicited positive SPT results, APT results (based on the scoring system by the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (12)), or both. Foods that tested positive on the SPT were not included in the APT. Patients avoided foods that yielded positive results in the SPT or APT, and those that caused IgE-mediated symptoms or anaphylaxis. The number of foods avoided was recorded and counted for each patient who had dietary or combination therapy.

Skin-prick Test

The 6 foods that cause >90% of IgE-mediated food allergic reactions were included for the SPTs. Patients had SPTs to cow's milk, hen's eggs, soy, wheat, a mix of peanuts and tree nuts, and a fish/shellfish mix with standardized extracts from Greer. Individual foods were added based on clinical history and dietary intake. Histamine (1 mg/mL) and normal saline were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Tests were read after 15 minutes and interpreted as positive if there was a ≥3-mm wheal reaction compared with that of the control (13).

Atopic Patch Test

Patients had APTs to 8 foods identified from previous groups as most causative in EoE (11), including cow's milk, hen's eggs, soy, wheat, peanut/tree nuts, fish/shellfish, beef, and chicken. APTs, however, were excluded for foods that caused a clinical allergic reaction or those that were positive on the SPT. Raw foods were used for APTs. Patches were removed after 48 hours and scored 72 hours after placement. A score of ≥2 was considered positive based on the 1+ to 3+ grading scale of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (12).

Topical or Oral Corticosteroids

Patients on topical corticosteroids received 1 to 2 mg of budesonide twice daily as an oral, viscous slurry or 88 to 440 μg oral fluticasone twice daily. The type and dose of corticosteroid were determined by the treating physician.

Combination Therapy

Patients began the combination of a test-based elimination diet and topical corticosteroid treatment (budesonide or fluticasone) at the time of diagnosis. Patients were included in this group if they received combination therapy for ≥3 months or until the next follow-up biopsy, whichever occurred earlier. Patients who failed single-therapy treatment before beginning the combination therapy were only included in the combination therapy group.

Remission Status

Clinical and histological remissions were dichotomized, and endpoints were determined before conducting the chart review. Clinical remission was defined as complete resolution of the presenting symptoms and no new symptoms for ≥3 months from the initiation of therapy. A lack of clinical remission was defined as the persistence of ≥1 presenting symptom or the development of new symptoms. Complete histological remission was defined as <15 eos/hpf. A lack of histological remission was defined as ≥15 eos/hpf.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics and outcome measures were stratified by treatment group and reported as frequencies with percentages or medians and minimum and maximum values. Univariate analysis compared patient characteristics between treatment groups using Fisher exact test or the Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate. Multiple logistic regression models were also used to compare the odds of clinical and histological improvement between treatment groups by estimating odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Variables that were significant at the 0.10 level in the univariate analysis were also included in the multiple logistic regression models. Otherwise, statistical significance was set at the 0.05 level.

RESULTS

Subjects

Six hundred and seventy charts of patients diagnosed as having EoE between January 2006 and December 2012 were reviewed with institutional review board approval. Among these charts, 9% (n = 63) met the inclusion criteria. A flow diagram showing enrollment of subjects is presented in Supplemental Digital Content, Figure 1. The primary reason for exclusion was lack of evidence of clinical symptoms and histological criteria. Fifty-one percent of patients (n = 32) received combination therapy, and 27% (n = 17) received only topical corticosteroids. Twenty-two percent of patients (n = 14) were placed on the test-based elimination diet at diagnosis. Demographic characteristics of the subjects are shown in Supplemental Digital Content, Table 1. The majority of patients enrolled in the present study were male (73%; n = 46). The median age at diagnosis was 8.3 years (range 0.7–20.7 years). Patients in the corticosteroid-only group tended to be older at diagnosis and at the initial visit compared to those in the dietary restriction and combination therapy groups (P < 0.05). All patients (100%, n = 63) presented with at least 1 gastrointestinal symptom, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, failure to thrive/weight loss, or diarrhea and received a PPI for 8 weeks before the first biopsy. Asthma and allergic rhinitis were more common among patients in the dietary restriction group (P < 0.05). Among the 63 enrolled patients, 95% (n = 60) continued to receive PPIs along with their respective treatment regimen after the first biopsy.

Clinical Remission in the Combination Therapy Group

Clinical remission for each treatment group is shown in Table 1. Complete resolution of the presenting clinical symptoms occurred more frequently (91%, n = 32) in patients who received combination therapy compared to that of patients in the topical corticosteroid (71%) or dietary restriction (64%) groups. This, however, did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.06). The unadjusted odds of clinical improvement were 4.6 times greater (95% CI: 1.1–18.8) in patients with combination therapy compared to that of either of the single therapies. The OR was 2.0 (95% CI: 0.3, 12.3) after adjusting for the time between repeat biopsies in this subgroup (n = 43). The odds of clinical improvement were 3.7 time greater (95% CI: 1.1, 12.7) among patients in the combination therapy group compared with that of the topical corticosteroid group after adjusting for corticosteroid dose.

TABLE 1.

Clinical and histological responses according to treatment group

| Variable | Steroid (N = 17) | Dietary restriction (N = 14) | Combination (N = 32) | P* |

| Time between biopsies | ||||

| N | 14 | 9 | 20 | |

| Median (min, max) | 0.5 (0.2, 2.9) | 0.8 (0.3, 3.9) | 0.7 (0.2, 6.5) | 0.22 |

| Baseline eos/hpf | ||||

| N | 17 | 14 | 32 | |

| Median (min, max) | 40 (20, 92) | 47.5 (20, 75) | 49.5 (19, 105) | 0.95 |

| Repeated eos/hpf | ||||

| N | 14 | 10 | 20 | |

| Median (min, max) | 9.5 (0, 102) | 9.5 (0, 100) | 0 (0, 25) | 0.07 |

| Change in eos/hpf† | ||||

| N | 14 | 10 | 20 | |

| Median (min, max) | −32 (−88, 72) | −29 (−50, 37) | −38.5 (−105, 5) | 0.26 |

| Remission, n (%) | ||||

| Clinical | 12/17 (71%) | 9/14 (64%) | 29/32 (91%) | 0.06 |

| Histological | 7/14 (50%) | 6/10 (60%) | 16/20 (80%) | 0.21 |

Eos/hpf = number of eosinophils per high-power field; max = maximum; min = minimum; N = number.

*P were determined by Fisher exact test or Kruskal-Wallis test.

†Computed as post-treatment minus baseline; negative values indicate a decline in eos/hpf.

Histological Remission in the Combination Therapy Group

Repeat biopsies were performed in 70% (n = 44) of the 63 patients in the present study. Although time between repeat biopsies did not significantly (P = 0.22) differ between groups, the dietary restriction group tended to have more time between biopsies (median = 0.8 years) compared with that of the topical corticosteroid (median = 0.5 years) and combination therapy (median = 0.7 years) group (Table 1, Fig. 1). Histological remission was higher among patients in the combination therapy group (80%) compared with those in the topical corticosteroid (50%) and dietary restriction groups (60%), but this was not statistically significant (Table 1). The unadjusted odds of histological remission were 3.5 times greater (95% CI: 1.2, 10.5) among patients in the combination therapy group compared with that of patients in the single-therapy groups. After adjusting for covariates, the OR was 3.5 (95% CI: 1.1, 11.2). The median change in number of eos/hpf was greatest in the combination group, although the difference between groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.07); the corticosteroid and food avoidance groups had relatively equivalent changes in eos/hpf (Table 1). Patients who received <176 μg corticosteroid in the combination group were more likely to respond than patients in the single-agent corticosteroid group who were treated with ≥176 μg corticosteroid (OR = 5.8, 95% CI: 0.9, 39); however, this estimate was underpowered. The combination therapy group and corticosteroid groups were comparable with 80% of patients receiving fluticasone, but the corticosteroid group was treated with a slightly higher dose (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Time between esophageal biopsies according to treatment group. F = dietary restriction; FS = combination therapy; S = steroid.

Table 2.

Comparison of steroid doses between FS and S groups

| FS | S | |

| Average dose, mg | 0.93 | 1.12 |

| Minimum dose, mg | 0.176 | 0.176 |

| Maximum dose, mg | 4 | 6 |

| Median dose, mg | 0.44 | 0.88 |

| Percent fluticasone | 80% | 80% |

FS = food plus steroid; S = maximum.

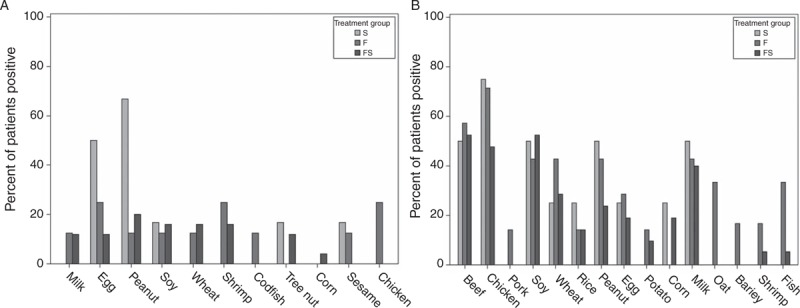

Atopy and Food Avoidance in Single and Combination Therapy Groups

The majority of patients had atopic diathesis, and 73% (n = 46) had atopic rhinitis. Asthma and eczema were less common at 51% (n = 32) and 37% (n = 23), respectively. Patients with dietary restriction tended to exhibit higher incidences of asthma and atopic rhinitis. The distribution of positive test results for the immediate-type hypersensitivity skin test (IHST) and patch test (APT) is shown in Figure 2. The 6 most common foods that yielded positive results in both the IHST and APT were chicken, beef, milk, peanut, soy, and wheat. On average, patients treated exclusively by food elimination (n = 10) avoided 5.1 (standard deviation = 1.8) foods, whereas those treated with the combination therapy (n = 38) avoided 3.5 (standard deviation = 2.1) foods. Sixty-two percent (n = 20) of patients who responded to combination therapy previously failed single-agent topical corticosteroid (n = 13) or food elimination therapy (n = 7). Sixteen of these 20 patients were defined as having “failure of therapy” based on continued clinical symptoms, and 2 were defined as having histological failures based on eos/hpf count >15.

FIGURE 2.

(A) Immediate-type hypersensitivity skin test (IHST) testing: percent of positive tests for food-specific IHST according to treatment group. (B) Patch testing: percent of positive tests for food-specific patches according to treatment group. F = dietary restriction; FS = combination therapy; S = steroid.

DISCUSSION

Currently, there is a debate regarding the ideal therapy for pediatric EoE. The first-line therapy in adults is a regimen of topical corticosteroids (14). Food elimination diets, however, are often considered in pediatric patients (1). This is the first study to evaluate food elimination compared to topical corticosteroids or a combination therapy in pediatric patients with EoE.

Utility of Test-based Food Elimination

The 2011 EoE consensus document recommends food avoidance diets in pediatric patients with EoE (1). The practical implementation of such diets, however, remains under debate. There are 3 major dietary options for food elimination: the elemental diet, SFED, and skin test-based avoidance (8). An elemental diet eliminates all foods, and nutrition is provided exclusively by a crystalline amino acid formula (8). The test-based diet is often conducted with empiric milk avoidance (15). Although the elemental diet is the most effective, compliance with this strategy is challenging for patients older than infant or toddler age (8,16). In addition, dietary restriction is generally associated with reduced quality of life (17).

Skin test elimination diets are controversial because of low specificity (∼50%) for positive values on IHST (8). In addition, EoE is thought to include a non-IgE-mediated pathophysiology; thus, positive IHST results are difficult to interpret as a sole marker of sensitization (8,16). Given the concern for non-IgE-mediated disease, patch testing is advocated. The test results are, however, subjective and lack standardization (8). Thus, SFED has become more popular, as testing is not required. Nonetheless, patient compliance remains difficult because of the high prevalence of foods containing these antigens (8).

In 2012, Henderson et al (8) compared these 3 diets and found that elemental diets are the most effective; however, there was no significant difference between SFED and test-based diets. In 2012, Spergel et al reported that SFED is as effective as food-specific elimination. Food-specific elimination diets, however, may exclude fewer foods (15). The present study confirms the effectiveness and utility of specific food elimination diets. The remission rate in this cohort was 64%, which is consistent with previously reported rates of 77% (Spergel et al) and 65% (Henderson et al). Interestingly, the top 5 foods to be removed were chicken, beef, milk, soy, and wheat. Most studies did not report chicken or beef among the most frequently removed foods (8,11,15). This distinction may be because of different methods of food preparation for APT. Chicken and beef were the 2 most frequently removed foods in this cohort. These results support the importance of carefully selecting the foods to be tested, as meats are not included in the SFED but appear to be important causative antigens. Prospective studies should be performed to confirm these findings.

Effectiveness of Combination Therapy

We report for the first time that corticosteroid therapy is more effective when combined with a test-based elimination diet compared to either strategy alone. There is limited literature comparing the efficacy of topical corticosteroids versus elimination diets in patients with EoE. In 2005, a 10-year retrospective review demonstrated an 81% response rate to topical corticosteroids in 17 patients with EoE compared to a 57% response rate in 132 patients treated with test-based dietary restriction and a 97% response in 164 patients treated with an amino acid–based formula (11). There was, however, a large variation among the numbers of patients in each group, and statistical analyses were not performed. There are no other reports from a single institution comparing topical corticosteroids to elimination diets.

Although each therapy offered benefit, the approach to combine corticosteroids with food elimination was also effective. This result was observed even in patients who failed previous individual therapy. One explanation for these results is that a patient may require that fewer foods be eliminated when corticosteroids are added; conversely, a lower dose of topical therapy may be required to achieve benefit when combined with food elimination. It is difficult to comply with dietary therapies owing to the number of avoided foods; thus, decreasing the number of foods that must be eliminated may improve compliance and quality of life (17). In addition, common parental concerns regarding topical corticosteroids include potential adverse effects and the need for indefinite treatment. The shorter median time between biopsies in corticosteroid-treated patients in this cohort is consistent with this concern. Using lower doses of topical corticosteroids, as in the combination group, may minimize long-term adverse effects and reassure parents.

In pediatric patients, diet should be comprised of 45% to 50% carbohydrates, 20% to 25% fats, and 15% to 20% protein (18). Fat and protein-containing foods are often eliminated from children's diets during SFED or skin test-based elimination (18). In addition, vitamin and mineral deficiencies may occur when multiple food groups are avoided (18). Fewer foods were eliminated when the combination therapy was applied, which may decrease nutritional deficiencies. The majority of safety data with topical corticosteroids is based on administration for asthma. It is, however, unclear whether oral treatment shows the same adverse effect profile in EoE as that of inhaled therapy. There are limited studies regarding the safety of topical corticosteroids in EoE; these studies have been based on <2 years of treatment (19–22). Although adrenal suppression and growth delay are potential adverse effects of corticosteroid’ use in asthmatic patients, these adverse effects have not yet been documented in EoE (23–26). The effects of the combination therapy on nutrition and on the adverse effects of topical corticosteroids remain unclear and warrant further study.

EoE is potentially a Th2-driven allergic reaction to food. Eotaxin-3 and interleukin-5 and -13, which induce eosinophil trafficking to the esophagus, are released in response to antigens (27,28). Elimination of foods from the diet may decrease the antigen burden, diminishing this immune reaction. Although the exact mechanism of corticosteroid therapy is unknown, studies show that eotaxin mRNA, interleukin-13 mRNA, and epithelial hyperplasia are reduced by topical corticosteroid therapy (29–31). We hypothesize that the reduced antigenic burden from food elimination and diminished inflammation by corticosteroids leads to inhibition of inflammatory pathways and the overall efficacy of combination therapy. In addition, as effects were also observed in a treatment-refractory population, this therapy may be more suitable for those who have failed previous therapy rather than as a front-line treatment option.

Limitations

The main limitation of the present study is the retrospective design. The individual preferences, allergy profiles, and concerns regarding corticosteroid’ adverse effects may have influenced the treatment group assignment. It is also possible that because the combination therapy group was younger, it included patients who were easier to treat; however, factors affecting treatment decisions were not recorded. The dietary group was also more atopic, so it might have included more difficult-to-treat patients, but the baseline eos/hpf in all groups was not statistically different (S, F, FS: 40, 47.5, 49.5 eos/hpf, respectively), so this is unlikely. There were a high proportion of patients who previously failed single therapy and this may bias the comparison between the 3 groups. The large subset of patients who lacked follow-up biopsies was also a concern, as some patients were not assessed histologically. There were, however, no differences in clinical response between those who received biopsies and those who did not.

CONCLUSIONS

The optimal treatment for pediatric EoE remains unknown. The present study shows that topical corticosteroids, test-based dietary elimination, and combination therapy are all effective treatment options for atopic patients with EoE. Combination therapy, however, is most effective in this cohort at inducing clinical remissions and fewer foods are avoided when compared to test-based dietary elimination. As combination therapy may be a second-line treatment in clinical practice, its ability to induce remission in patients who failed single therapy is important. Future prospective studies are warranted to confirm our findings that food elimination combined with corticosteroids offers an alternative treatment option for patients who are refractory to single-agent therapy.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Drs Seth and Chokshi contributed equally to this manuscript.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 128:3.e6–20.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soon IS, Butzner JD, Kaplan GG, et al. Incidence and prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013; 57:72–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeBrosse CW, Franciosi JP, King EC, et al. Long-term outcomes in pediatric-onset esophageal eosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 128:132–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Dohil R, et al. Esophageal remodeling in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 119:206–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucendo AJ, Castillo P, Martin-Chavarri S, et al. Manometric findings in adult eosinophilic oesophagitis: a study of 12 cases. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 19:417–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konikoff MR, Noel RJ, Blanchard C, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluticasone propionate for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2006; 131:1381–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexander JA, Jung KW, Arora AS, et al. Swallowed fluticasone improves histologic but not symptomatic response of adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 10:742.e1–749.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henderson CJ, Abonia JP, King EC, et al. Comparative dietary therapy effectiveness in remission of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 129:1570–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kagalwalla AF, Sentongo TA, Ritz S, et al. Effect of six-food elimination diet on clinical and histologic outcomes in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4:1097–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kagalwalla AF, Shah A, Li BU, et al. Identification of specific foods responsible for inflammation in children with eosinophilic esophagitis successfully treated with empiric elimination diet. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2011; 53:145–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spergel JM, Andrews T, Brown-Whitehorn TF, et al. Treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis with specific food elimination diet directed by a combination of skin prick and patch tests. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2005; 95:336–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilkinson DS, Fregert S, Magnusson B, et al. Terminology of contact dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol 1970; 50:287–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eigenmann PA, Sampson HA. Interpreting skin prick tests in the evaluation of food allergy in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 1998; 9:186–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Straumann A. Eosinophilic esophagitis: rapidly emerging disorder. Swiss Med Wkly 2012; 142:w13513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Cianferoni A, et al. Identification of causative foods in children with eosinophilic esophagitis treated with an elimination diet. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 130:461.e5–467.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arora AA, Weiler CR, Katzka DA. Eosinophilic esophagitis: allergic contribution, testing, and management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2012; 14:206–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franciosi JP, Hommel KA, Bendo CB, et al. PedsQL eosinophilic esophagitis module: feasibility, reliability, and validity. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013; 57:57–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santangelo CM, McCloud E. Nutritional management of children who have food allergies and eosinophilic esophagitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2009; 29:77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoepfer AM, Simon D, Straumann A. Eosinophilic oesophagitis: latest intelligence. Clin Exp Allergy 2011; 41:630–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dellon ES, Sheikh A, Speck O, et al. Viscous topical is more effective than nebulized steroid therapy for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2012; 143:321.e1–324.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, et al. Long-term budesonide maintenance treatment is partially effective for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9:400.e1–409.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brazzini B, Pimpinelli N. New and established topical corticosteroids in dermatology: clinical pharmacology and therapeutic use. Am J Clin Dermatol 2002; 3:47–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zollner EW, Lombard C, Galal U, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression in asthmatic children on inhaled and nasal corticosteroids--more common than expected? J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2011; 24:529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwartz RH, Neacsu O, Ascher DP, et al. Moderate dose inhaled corticosteroid-induced symptomatic adrenal suppression: case report and review of the literature. Clin Pediatr 2012; 51:1184–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watkins L, Soriano JB, Mortimer K. Getting risks right on inhaled corticosteroids and adrenal insufficiency. Eur Respir J 2013; 42:9–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chauhan BF, Chartrand C, Ducharme FM. Intermittent versus daily inhaled corticosteroids for persistent asthma in children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 2:CD009611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.di Pietro M, Fitzgerald RC. Research advances in esophageal diseases: bench to bedside. F1000prime Rep 2013; 5:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rothenberg ME. Biology and treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2009; 137:1238–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonsalves N, Yang GY, Doerfler B, et al. Elimination diet effectively treats eosinophilic esophagitis in adults; food reintroduction identifies causative factors. Gastroenterology 2012; 142:1451.e1–1459.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blanchard C, Mingler MK, Vicario M, et al. IL-13 involvement in eosinophilic esophagitis: transcriptome analysis and reversibility with glucocorticoids. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 120:1292–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis CJ, Lamb CA, Kanakala V, et al. Is the etiology of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults a response to allergy or reflux injury? Study of cellular proliferation markers. Dis Esophagus 2009; 22:249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.