Abstract

High rates of local recurrence in tobacco-related head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) are commonly attributed to unresected fields of precancerous tissue. Since they are not easily detectable at the time of surgery without additional biopsies, there is a need for non-invasive methods to predict the extent and dynamics of these fields. Here we developed a spatial stochastic model of tobacco-related HNSCC at the tissue level and calibrated the model using a Bayesian framework and population-level incidence data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry. Probabilistic model analyses were performed to predict the field geometry at time of diagnosis, and model predictions of age-specific recurrence risks were tested against outcome data from SEER. The calibrated models predicted a strong dependence of the local field size on age at diagnosis, with a doubling of the expected field diameter between ages at diagnosis of 50 and 90 years, respectively. Similarly, the probability of harboring multiple, clonally unrelated fields at the time of diagnosis were found to increase substantially with patient age. Based on these findings, we hypothesized a higher recurrence risk in older compared to younger patients when treated by surgery alone; we successfully tested this hypothesis using age-stratified outcome data. Further clinical studies are needed to validate the model predictions in a patient-specific setting. This work highlights the importance of spatial structure in models of epithelial carcinogenesis, and suggests that patient age at diagnosis may be a critical predictor of the size and multiplicity of precancerous lesions.

Major Findings

Patient age at diagnosis was found to be a critical predictor of the size and multiplicity of precancerous lesions. This finding challenges the current one-size-fits-all approach to surgical excision margins.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, field cancerization, local recurrence, surgical margins, tobacco

Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) arises in the epithelial lining of the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx. The annual incidence rate of HNSCC is estimated to be around 600,000 new cases worldwide (1), and in the US alone the death toll is approximately 11,500 cases per year (2). While a subgroup of HNSCC, including the oropharynx, is caused by infection with high-risk types of the human papillomavirus (HPV) (3), the majority of HNSCC are HPV-negative and primarily associated with tobacco use and alcohol consumption (1). Despite a growing number of therapeutic strategies, survival in HPV-negative HNSCC has not improved significantly over the past decades, with a low median survival of approximately 20 months (4).

Poor prognosis in tobacco-related head and neck cancers is commonly attributed to the development of local recurrences and metastases after removal of the primary tumor (1). Field cancerization, or the presence of premalignant fields surrounding the primary tumor, has been shown to drive the high rate of local recurrence (5–11). In fact, molecular studies have shown that the majority of HPV-negative HNSCC develop within local fields of premalignant cells that are clonally related to the resected primary cancer (7,9). These fields can be much larger than the actual carcinoma and are generally difficult to detect without genomic analyses due to their visually normal appearance (12). If such an invisible premalignant field extends beyond the surgical margins, the portion of the field left behind after resection of the primary tumor increases the risk of subsequent recurrence and contributes to poor prognosis (11). The occurrence of precancerous fields was first reported by Slaughter and colleagues (5) and has since been documented in most epithelial cancers (10,13–15).

To date, it remains difficult to account for the phenomenon of field cancerization in clinical practice. The main reason for this translational barrier is a poor understanding of the dynamics and geometry of these invisible fields. Indeed, it is impossible to account for the risk factor of an unresected field of precancerous tissue in absence of any information on the extent of the suspected field. To overcome this barrier, we synthesized data and knowledge sources from the tissue, clinical and population scales to develop a quantitative model of HNSCC carcinogenesis that accounts for spatial features of the precancer field. Based on this model, we then sought to identify aspects of standard clinical practice that could be improved by means of patient-specific modeling tools.

Methods

Biological mechanism of carcinogenesis

To model the carcinogenesis of tobacco-related HNSCC, we first developed a spatial stochastic model of homeostasis in stratified squamous epithelia of the head and neck. The homeostatic epithelia of this region undergo periodic bottom-up renewal (16), whereby long-lived progenitor cells (PC) in the basal layer of the epithelium give rise to transit amplifying cells (TAC) of limited proliferative potential (17,18). As they divide, the TAC move towards the superficial layers of the stratified epithelium, where they eventually exit the cell cycle and get sloughed off at the tissue surface. Since differentiating TAC are lost from the tissue within a few weeks (16), they are unlikely to contribute to the emergence of a neoplastic clone of cells, and it suffices to focus on the population of PCs in the bottom layer of the epithelium.

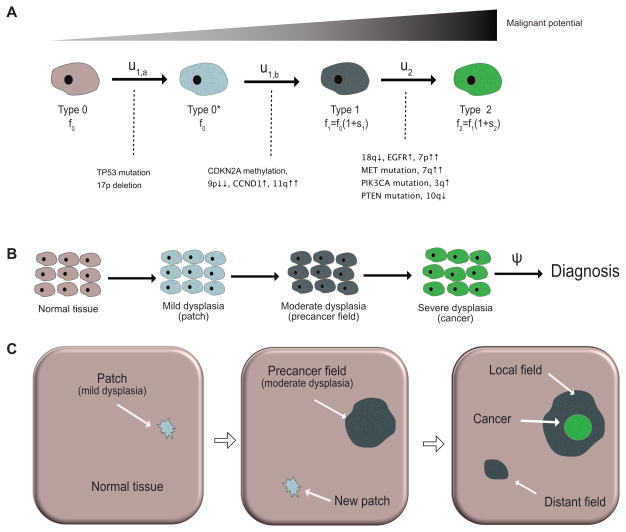

The transformation from normal to cancerous cells is largely attributed to the successive accumulation of (epi)genetic aberrations, see Figure 1A. Once a normal PC has acquired a growth advantage, the resulting clone of mutant cells starts spreading across the affected epithelium by replacing adjacent cells of lower proliferative potential (19). There are a multitude of genetic alterations commonly found in HPV-negative HNSCC (1), but both the total number and temporal ordering of events necessary for cancer initiation are patient- and tumor-specific (20). In view of this genotypic heterogeneity, we focused on the phenotypic progression instead. Indeed, the majority of tobacco-related HNSCC progress through a series of precancerous stages called epithelial dysplasia, see Figure 1B (21,22). These stages are histopathologically classified into three categories: mild, moderate and severe dysplasia (carcinoma in situ [CIS]) (23). Based on this observation, we modeled neoplastic progression at the cellular level in 4 stages (Figure 1A), developing from normal cells (type 0) into mildly dysplastic cells (type 0*), into moderately dysplastic cells (type 1), and eventually into severely dysplastic cells (type 2).

Figure 1. Stochastic model of carcinogenesis in HPV-negative HNSCC.

(A) At the cellular level, accumulation of genetic alterations leads to increasingly malignant phenotypes. The cellular mutation rates between normal (type 0), dysplastic (type 0*, type 1) and cancerous (type 2) cells are indicated above the solid arrows. The type-specific proliferation rates fi depend on the relative selective advantages si as specified. Genetic events associated with the phenotypic transitions are listed below the solid transition arrows, see (1); the number and temporal ordering of these events is not unique. (B) At the tissue level, carcinogenesis manifests itself through the emergence of a patch of mild dysplasia, which can give rise to a field of moderate dysplasia (the precancer field). The first viable cancer cell arises within the growing precancer field, leading to carcinoma in situ and eventually invasive HNSCC. The time between cancer initiation and diagnosis is modeled as an exponential random variable with rate ψ. (C) At the organ level, a possible scenario of carcinogenesis is illustrated in three consecutive snapshots. Left: a small patch of mild dysplasia (neutral evolution) appears in the normal tissue. Middle: the patch gives rise to a positively selected precancer field that expands into the normal epithelium; clonally unrelated patches of mild dysplasia may arise at any time. Right: the precancer field that gives rise to the primary tumor is called the local field, whereas the clonally independent precancer field that starts growing is referred to as a distant field.

Although the number and ordering of mutations responsible for HNSCC carcinogenesis are not unique, a better understanding of the genetic underpinnings and fitness landscapes of the phenotypic transitions enhances the mechanistic foundation of the model, see Figure 1A. It is generally accepted that loss of function of the tumor suppressor gene TP53, either through mutation or loss of heterozygosity, is an early event during tumorigenesis of HNSCC. Indeed, histopathological studies have found that expanding cancer fields are preceded by small TP53 mutated patches (<200 cells in diameter) (8). Two studies (21,22) found no significant differences in proliferation index for low-grade dysplasia compared to normal tissue, even though mutant TP53 was significantly elevated in low-grade dysplasia (22). This suggests that a likely first step of tumorigenesis is the formation of an evolutionarily neutral patch (mild dysplasia) of TP53+/− cells. Once a cell within this patch acquires a further genetic aberration, either through methylation or deletion of CDKN2A (24), or through gain or amplification of CCND1 (25), the resulting clone has a selective advantage over its neighboring cells and causes the emergence of an expanding precancer field (26). Once the field starts expanding, further hits to the EGFR or TGFβ pathways can lead to moderate dysplasia, CIS, and eventually invasive HNSCC.

Microscopic model of carcinogenesis

To capture the spatial dynamics of the above mechanisms of carcinogenesis, we developed a stochastic Moran model on a regular two-dimensional lattice (27,28). Initially, all cells on the lattice are normal PCs (type 0) and proliferate at rate f0. Cell division is stochastic, and when a PC divides, one daughter cell replaces the mother cell, and the other daughter cell replaces one of the nearest neighbor cells on the lattice, chosen uniformly at random. Each normal cell can, at rate u1,a, acquire a mutation to become a mildly dysplastic cell (type 0*). At the tissue level, this leads to a patch of dysplasia as illustrated in the first panel of Figure 1C. The proliferation rate of type 0* cells is still f0, but acquisition of a second hit, at cellular rate u1,b, can transform type 0* cells into precancerous cells (type 1). Type 1 cells in turn have a proliferative advantage f1=f0(1+s1) over type 0 and type 0* cells, and can clonally expand as precancerous fields of moderate dysplasia by replacing neighboring cells of lower proliferative potential, see second panel in Figure 1C. Mathematically, we can simplify the model by deriving the effective mutation rate u1 from type 0 to type 1 cells: the probability v01 that a type 0* cell gives rise to growing field of type 1 cells before its progeny dies out is given by (27)

| (1) |

where . At rate u2, type 1 cells in turn can mutate into malignant (type 2) cells that initiate growth of cancer, see third panel in Figure 1C. Cancer cells have a fitness advantage of s2 over type 1 cells and hence divide at rate f2=f1(1+s2). Finally, the time between onset of CIS and diagnosis was modeled as an exponentially distributed random variable with rate ψ, see Figure 1B. The reason for this simplified transition model from first cancer cell to diagnosis is two-fold. First, upon penetration of the basement membrane and infiltration of the stroma, the epithelial architecture is irreversibly disrupted and the microscopic dynamics with lateral displacement no longer apply; second, depending on the location of the lesion and the patient's behavior, time to clinical diagnosis can be highly variable.

Mesoscopic model approximation

We previously derived the following mesoscopic approximation to the spatial model that enables analytical calculations of waiting times and field geometries (28,29). In the mesoscopic model, the arrival of expanding type 1 clones is a stochastic Poisson process with rate Nu1s̄1. The factor s̄1 accounts for the fact that the progeny of a new type 1 cell will either fluctuate to extinction with probability 1 – s̄1 or expand indefinitely with probability s̄1. Next, we characterized the growth of an expanding type 1 clone based on a shape theorem (30). According to the theorem, expanding type 1 clones asymptotically grow as a convex symmetric shape with constant radial growth rate c2. Simulations of the process show that this shape can be approximated as a disk or circle, see (29). The rate c2 in turn depends on the selective advantage s1. For small s1 it scales as where f(s) ~ g(s) means that f(s)/g(s) → 1 as s → 0 (28); for larger values of s1, we used numerical simulations to estimate the value of c2, see Figure 3 in (29). In particular, for s1 > 0.5, we found an approximately linear dependence c2(s1) ≈ 0.6s1 + 0.22 (29. Finally, we note that multiple precancer fields of type 1 cells can coexist as illustrated in Figure 1C.

Incidence data

To parameterize the tissue-level model and ensure its compatibility with population-level data, we calibrated the mesoscopic approximation of the microscopic model based on age-specific incidence rates from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute (18 Registries, 2000–2012) in a Bayesian framework. Since we focused on HPV-negative cancers, we restricted our search to males and females diagnosed with malignant tumors in the following categories of Site Recode ICD-O-3/WHO 2008: lip; tongue; floor of mouth; gum and other mouth; hypopharynx; larynx (31). We further excluded cases with primary site labeled as C01.9-Base of tongue because cancers at this site are commonly HPV-positive (32). We derived the number of susceptible individuals and the number of cancer cases diagnosed in each of the following age groups: 15–19 years, 20–24 years,…, 80–84 years, and 85+ years. We note that the age-specific incidence curve for HPV-negative HNSCC has a peaked profile, see Figure 2A. However the model developed here predicts monotonically increasing incidence rates and thus cannot recapitulate peaked incidence patterns. Because changing baseline risks are more likely to cause the peaked profile than changes in biological parameters (see Supplemental Information S1), we truncated the incidence data used for parameter inference at age 74 instead of introducing additional age-dependent model parameters. The vast majority of HPV-negative HNSCC are attributed to tobacco consumption (33,34); thus we reduced the pool of susceptible individuals to the approximately 20% of current smokers within the considered age groups (35). Furthermore, we assumed the exposure to start at age 15 years (36,37).

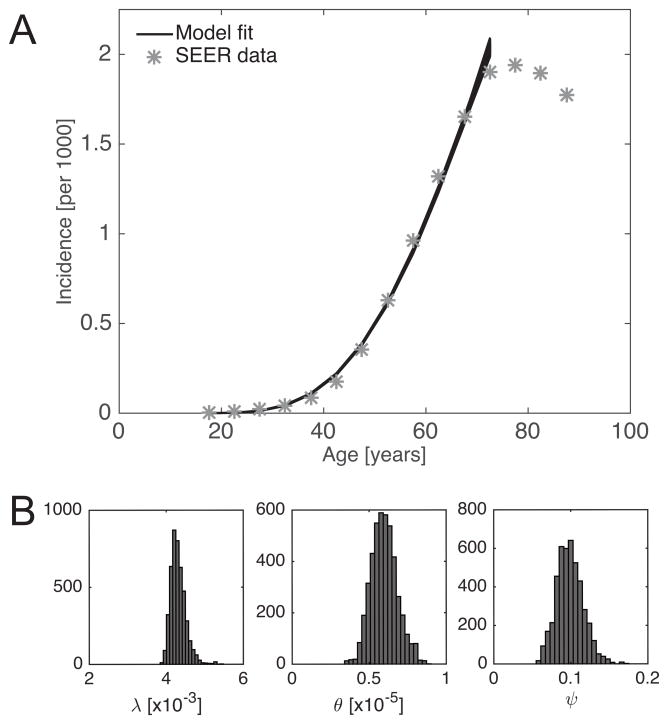

Figure 2. MCMC summary.

MCMC Metropolis Hastings algorithm was used to infer the posterior distribution of the model parameters λ, θ and ψ. A total of 500,000 iterations were computed; the first 50,000 burn-in iterations were discarded, and then 1 in 100 samples was used to estimate the posterior distribution. (A) Model fit to SEER data; age-specific incidence is restricted to smokers (see main text for details). The data point at 85 years reflects the incidence estimate for patients aged 85 years and older. (B) Marginal distributions of λ, θ and ψ.

Parameter inference

To compare the model predictions with SEER data, we first derived the age-specific incidence function under the evolutionary model at the tissue-level. To this end, we defined the random variable σ3 as the time from mean age at smoking initiation to diagnosis with invasive cancer, and calculated the survival function

| (2) |

where

| (3) |

is the lower incomplete Γ-function, and ψ is the transition rate from onset of CIS to diagnosis. The parameter groups (3) have the following interpretation: λ is the initiation rate of expanding type 1 clones, see also previous paragraph; θ can be rewritten as , where is approximately the time it takes for an expanding type 1 clone to give rise to an expanding type 2 clone (28). Based on S(t) we then computed the hazard function h(t) = −S′(t)/S(t), which provides a direct link to the SEER-derived age-specific incidence rates. The derivation of the likelihood function used for inference is outlined in Supplemental Information S1.

We then used a computational Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Metropolis Hastings algorithm to derive posterior distributions for the parameters λ, θ and ψ. We used improper priors over [0, σ) for all three parameters and ran a Markov chain of length 500,000. Computations were performed in MATLAB (Version 8.5.0, The MathWorks Inc. 2015). To determine plausible initial conditions and step lengths for the MCMC algorithm, we independently estimated the three parameter groups based on literature estimates of the underlying biological parameters, see Supplemental Information S2. After discarding the first 50,000 burn-in steps, we sampled every 100th step to characterize the posterior distributions. Convergence to steady-state was visually ascertained. 95% credible intervals for the posterior distributions were computed by discarding the 2.5% largest and smallest values for each parameter. The marginals of the posterior distributions for λ, θ and ψ are summarized in Figure 2B. Median estimates and 95% credible intervals of the posterior distributions, together with the literature-based order of magnitude estimates are summarized in Table 1. Goodness of fit was deemed satisfactory based on visual inspection, see Figure 2A.

Table 1. Parameter estimates: MCMC and literature-based.

For each parameter, the median and 95% credible intervals for the MCMC Metropolis-Hastings derived posterior distributions and the literature-based estimates are shown. y=year.

| Parameter | Units | Prior | Median | 95% Credible Interval | Literature Estimates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ | [y−1] | [0, σ) | 4.3 10−3 | (4.0 10−3, 4.8 10−3) | ~10−3 |

| θ | [y−3] | [0, σ) | 5.9 10−6 | (4.4 10−6, 7.9 10−6) | ~10−4 |

| ψ | [y−1] | [0, σ) | 9.8 10−2 | (6.7 10−2, 13.5 10−2) | ~10−1 |

To compare model predictions with clinical recurrence patterns, SEER (13 Registries, 1991–2011) was queried for a retrospective analysis of the recurrence risk in patients diagnosed and treated for HNSCC lesions of size ≤ cm. Data extraction was performed using a MP-SIR session with the software SEER*Stat (http://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat). Again, we focused on the predominantly HPV negative sites as specified under Model calibration. Only patients aged 18–85 years at diagnosis with a known tumor size of ≤ 30mm were included. Patients with unknown surgery status, unknown radiation status, and those identified at autopsy or on death certificate only were excluded. The following categorical variables were extracted from the dataset: age at diagnosis (younger: 18–49 years, older: 50–85 years) and treatment (surgery only, radiation only, surgery and radiation). For each patient, the time from diagnosis to recurrence (defined as second malignant event in any of the included head and neck sites), death, or censoring (defined as the minimum of end-of-study, loss to follow-up, and 10 years) was calculated. For each of the three treatment groups with known treatment status, a univariate Cox proportional-hazards regression for recurrence was performed based on the categorical age at diagnosis variable, stratified into younger (<50 years) and older (≥50 years) patients. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to visualize the results. Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals were computed, and all p-values were calculated as two-sided with significance declared for p-values below 0.05. Computations were performed in R (http://www.R-project.org).

Results

Local field size at diagnosis

To characterize the field geometry at time of diagnosis with invasive cancer, we first derived the size distribution of the local field. More precisely, denoting the radius of the local field at time t by Rt(t), we conditioned on {σ3 = t} to compute the probability density function of the local field radius as follows:

| (4) |

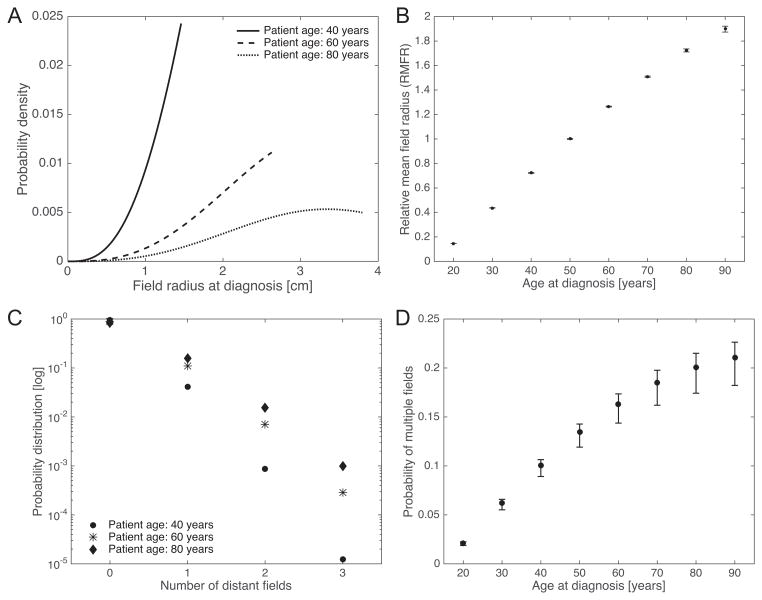

where . We refer to Supplemental Information S3 for details of the calculation. The corresponding density functions (4) for ages at diagnosis of 40, 60, and 80 years are shown in Figure 3A. Unfortunately, these results have an explicit dependence on the radial growth rate of the precancer field, c2(s1), which cannot be directly estimated due to identifiability constraints (we used literature-based estimates instead). To overcome this issue, we focused on the relative size of a precancerous field compared to the field size at age 50. More precisely, we introduced the relative mean field radius (RMFR), defined as the mean field radius at a given age divided by the mean field radius at age 50 years. Indeed, the RMFR is completely specified by the inferred parameters λ, θ and ψ, and does not explicitly depend on c2 (see Supplemental Information S3). Based on the posterior distributions from the Bayesian inference, we computed the RMFR as a function of patient age at diagnosis in Figure 3B. The model predicted an approximately linear increase in RMFR between the ages of 20 to 90 years, and the median (95% credible interval [CI]) RFMR at age 90 was found to be 1.90 (1.88, 1.93).

Figure 3. Field characteristics as a function of age at diagnosis.

(A) The probability density function of the field radius at diagnosis is shown for patient ages 40, 60 and 80 years, respectively. Calculations were performed using the median posterior values of λ, θ and ψ as shown in Table 1, and c2 = 0.4, see also Supplemental Information S2. (B) Based on the posterior distributions, the statistics of the relative mean field radius (RMFR) for different ages at diagnosis were computed. Median and 95% credible intervals (CI) are shown. (C) The probability distribution of the number of distant fields is shown for patient ages 40, 60 and 80 years, respectively. Parameter values as in (A). (D) The probability of multiple unrelated fields at time of diagnosis was computed based on the posterior distributions. Median and 95% CI are shown.

Multiple fields at diagnosis

In addition to the local field size at diagnosis, we estimated the probability of harboring distant fields in addition to the local field. The exact distribution of the total number M(t) of clonally independent fields, including the local and all distant fields, is found in Supplemental Information S3. In Figure 3C, the probability distribution for the number of multiple fields is shown for different ages at diagnosis (40, 60 and 80 years), based on the median posterior values of λ, θ and ψ. Using this distribution, we then computed the probability of harboring at least two clonally unrelated fields in the head and neck region at time of diagnosis,

| (5) |

Accounting for the posterior distributions of the parameter groups, the probability of harboring at least one distant field is shown as a function of age at diagnosis in Figure 3D. The model predicts that the probability (95% CI) of harboring at least one distant field increases by one order of magnitude from 2.1% (2.0%, 2.4%) at age 20 to 20.0% (18.6%, 22.7%) at age 80.

Age-specific recurrence patterns

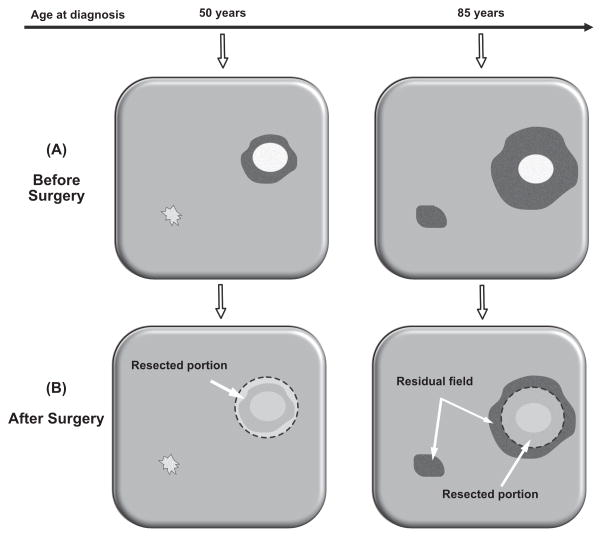

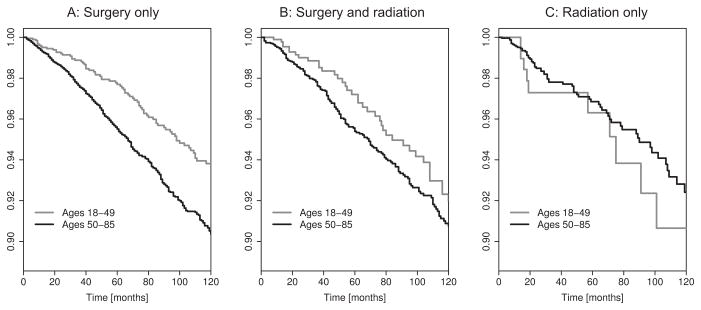

To test the validity of our model, we made model-based predictions and tested them against outcome data from SEER. The first prediction was based on the fact that current clinical practice recommends an age-independent excision margin width of ~1cm (38,39). Considering the predicted increase of local field size with age at diagnosis (Figure 3A), an age-independent margin width implies that, for the same tumor size, the area of precancerous tissue left behind after resection of a primary tumor is bigger in older patients (with larger precancer fields) compared to younger patients (with smaller precancer fields), see Figure 4. This increase in recurrence risk in older patients is further increased by the elevated probability of harboring distant fields (Figure 3B) that may not be affected by local excision of the primary tumor. To test the resulting hypothesis of an age-dependent recurrence risk, we performed a retrospective time-to-event analysis for patients with small ≤3cm) tumors who received surgery but no radiation (n=9,665). In alignment with our model-based prediction, we found a 58% increase in recurrence risk in older patients (≥50 years, n=7,774) compared to younger patients (<50 years, n=1,891) (Hazard Ratio [HR]: 1.58, 95% confidence interval [CI] =(1.27,2.10), p<.0001). The corresponding Kaplan-Meier curve for recurrence-free survival is shown in Figure 5A.

Figure 4. Surgical margins and residual field.

(A) Illustration of age-related differences in local field size and number of unrelated fields. Before surgery, only one local field may be present in a younger patient (left), whereas a larger local field and additional distant fields may be present in an older patient (right). (B) During surgery the local field is removed in the younger patient (left), but only partially resected in the older patient (right), where the residual field portions elevate the risk of recurrence.

Figure 5. Recurrence-free survival after treatment of primary tumor.

Recurrence-free survival among younger (<50 years) and older (≥50 years) patients, stratified by treatment regime: (A) surgery only; (B) surgery and radiation; (C) radiation only. Analyses restricted to primary tumors of size ≤3cm. Significant difference in recurrence risk for surgery only, p<.0001.

Because adjuvant radiation therapy after surgery targets the margins of the resected tissue portion, the combination of surgery and radiation is more likely to eradicate the entire local field and hence diminish the recurrence risk from a residual field portion. Therefore, we hypothesized a reduction in the age-related difference in recurrence risk among patients who received radiation in addition to surgery. This prediction was corroborated by the analysis of outcome data. Repeating the above time-to-event analysis for patients who received both surgery and radiation, we found a smaller, non-significant difference (HR=1.29, 95% CI=(0.91,1.84)) between older (≥50 years, n=4,537) and younger patients (<50 years, n=993), see Figure 5B.

Finally, we note that for the patient group with radiation but without surgery (Figure 5C), no significant difference in recurrence risk between the two age groups was observed. Interestingly, in comparison to younger patients (<50 years, n=266), older patients (≥50 years, n=2,622) did have a slightly smaller recurrence risk: HR=0.78, CI=(0.40,1.52). However, we were not able to draw any definite conclusions because of a small sample size and patient attrition in the younger age group.

Discussion

Leftover fields of precancerous tissue that are not removed during resection of HPV-negative, tobacco-related HNSCC lead to an increased risk of local recurrence. Due to their visually normal appearance, epithelial precancer fields are generally not detectable at the time of surgery without harmful biopsies of the surrounding tissue portions. Thus there is a need for non-invasive methods to predict the extent of the field and to make patient-tailored decisions with respect to optimal treatment modality, size of excision margins, and frequency of postoperative surveillance. In this work, we developed and calibrated a mechanistic model of spatial tumorigenesis in tobacco-related HNSCC. Following the lines of previous multi-scale modeling work (40–43), we linked biological mechanism at the tissue scale to data at the population scale and used a Bayesian framework to ensure compatibility of the model dynamics across scales. Using the model we made predictions about the geometry of precancerous fields at the time of diagnosis with invasive cancer and tested them against outcome data.

The models predicted a strong dependence of the local field size on age at diagnosis. More precisely, we found the expected field size of the local precancerous field surrounding the primary tumor to double between the ages of 50 and 90 years. The model further predicted a substantial increase in the probability of harboring independent synchronous fields at the time of diagnosis, increasing to 20% at age 80. Together, these findings indicate that the current one-size-fits-all approach to the width of surgical excision margins may need to be critically reevaluated.

Based on the model predictions, we hypothesized that larger local fields and a higher risk of harboring multiple fields in older patients would translate into a higher recurrence risk in older compared to younger patients when treated by surgery only. We tested this hypothesis by analyzing recurrence patterns in younger (<50 years) and older (≥50 years) patients who received surgery without radiation. As predicted, we found a higher risk of local recurrence in older patients compared to younger patients. In contrast, we did not find a statistically significant age effect in patients who received adjuvant radiation therapy. This is consistent with the observation that radiation is less focalized than surgical excision and hence is more likely to remove the surrounding field portions, even in older patients with larger fields. In addition, radiation may have an age-specific effect on local recurrence that is independent of the field size. For example, studies on the effects of radiotherapy in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ reported a higher likelihood of recurrence in patients who received adjuvant radiation therapy compared to those who did not (44,45). It is important to note that the observed recurrence patterns may be due to a combination of several biological and clinical factors, not just the age-related size of the precancer field.

Our study has several limitations. First, inherent limitations of the SEER database such as ascertainment biases and incomplete recurrence records may impact the validity of our results (46). Second, HPV status is not recorded in SEER, and despite careful selection of sites that are predominantly HPV-negative, a portion of recorded cases may have been misclassified. Third, although the incidence data used for model calibration was restricted to a relatively short period (2000–2012), it is likely subject to secular trends that are at least partially due to changing smoking patterns in the population (4,47). In addition, it has been shown that smoking cessation leads to a slow decrease in head and neck cancer risk (48), which may result in differential field sizes between former and current tobacco users. In future work, the use of more granular smoking prevalence and cancer incidence data, adjusted for secular trends, is expected to address these issues and improve the model predictions. Fourth, a limitation shared with most multistage modeling analyses is the assumption of identical parameters for all individuals. This issue is partially mitigated by the Bayesian approach, which provides posterior distribution of parameters rather than point estimates. However, incorporating patient-level heterogeneity into the modeling framework constitutes a critical next step toward the long-term goal of developing personalized approaches to head and neck cancer care. Finally, we did not explicitly account for the role of the immune system as a first line of defense against neoplastic progression. Although immune effects could be incorporated into the model, current knowledge about the exact mechanisms of immune response to neoplastic transformation seems insufficient to develop meaningful models.

Historically, different types of multistage models have been used to infer the nature of cancer-causing mechanisms based on incidence and mortality data. The first such models (49) were based on the assumption that cancer arises as the product of an organ-specific number of rare mutations. These models assumed a well-mixed population of cells and neglected cellular dynamics and spatial tissue structure. Later, these models were extended to account for clonal expansions of precancerous cells (40,41,50), and used to analyze the number and size of premalignant clones in non-spatial populations, both for exponential mean growth (51) and more general growth dynamics (52,53). In parallel to multistage models, population dynamic models such as the Wright-Fisher and Moran processes have also been used to model cancer initiation under well-mixed assumptions (54,55). In these models, the expansion of premalignant clones is constrained by competition with healthy cells or premalignant cells at other stages. Our current work constitutes an extension of both multistage and population dynamic models. In particular, we accounted for the spatial structure of the epithelial lining of head and neck sites, and we developed a mechanistic model based on the current understanding of tissue homeostasis and molecular biology of HPV-negative HNSCC. Using the spatially explicit model we achieved a very good fit to the SEER-based incidence data, Figure 2A. For the sake of comparison, we also fitted the classical multistage model (49) to the incidence data, see Supplemental Information S4. While the inferred number of 3 stages corresponds well to the current understanding of HNSCC etiology, the model fit was found to be poor. More recently, Brouwer and colleagues (47) showed that non-spatial two-stage clonal expansion models yield good fits to the data when accounting for period and cohort effects in biologic parameters. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that for solid cancers subject to field cancerization, spatial effects may play an important role in shaping population-level incidence patterns.

While our predictions for age-dependent recurrence risks and field sizes were successfully corroborated by SEER-based outcome data, pathological studies are needed to provide a definite confirmation of our models. Our predictions of an increase in field size in older patients will hopefully spur a critical re-evaluation of the one-size-fits-all approach to surgical excision margin width, as well as the effectiveness of surgery without radiation therapy in older patients with extended exposure and potentially very large fields. In addition, appropriate follow-up intervals for the monitoring of local recurrences may be optimized according to patient-specific predicted field geometries, and a quantitative understanding of the field dynamics combined with a set of reliable biomarkers for pre-malignant fields may enable physicians to perform targeted risk-assessments in high-risk groups, such as heavy smokers. Finally, the proposed modeling framework can be applied to other two-dimensional epithelial sites affected by field cancerization, such as bladder, esophagus and skin, and it may provide valuable insights into observed differences in field extent and outcome between HPV-positive and HPV-negative head and neck cancers.

Supplementary Material

Quick Guide to Equations and Assumptions.

Model assumptions

We developed and calibrated a spatial stochastic model of tobacco-related head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) at the tissue level. The major model assumptions are:

(Epi)genetic events lead to mutated cells with increased fitness advantage, and mutant clones can spread through the basal layer of the affected epithelium prior to onset of invasive cancer.

Due to the time scales of carcinogenesis, only long-lived progenitor cells in the basal layer of the epithelium are relevant; this monolayer of progenitor cells is modeled as a two-dimensional lattice, where each node is occupied by a cell.

Wild type and mutant progenitor cells undergo evolutionary competition in the basal layer; only nearest-neighbor interactions are considered.

Tissue architecture and homeostasis are maintained (constant population size) until the invasive cancer stage.

Key model parameters

Total population size (N); cellular transition rates from normal to precancer (u1), and from precancer to carcinoma in situ (u2), respectively; relative proliferative advantage of precancer (s1) and carcinoma in situ cells (s2); mean sojourn time from preclinical lesion to clinical diagnosis with cancer (1/ψ).

Key equations

We were interested in quantifying the geometry of the field of precancerous cells surrounding the tumor at time of diagnosis (σ3). The key equations are:

-

The survival function (probability that cancer has not been diagnosed by time t) of the model,

where γ is the incomplete gamma function, λ ≡ Nu1s̄1 and .

-

Conditioned on diagnosis occurring at time t, the probability density function of the radius of the precancer field that surrounds the primary tumor,

for all r ∈ [0, c2t], zero otherwise, where c2 is the radial expansion speed of the precancer field and

- Conditioned on diagnosis occurring at time t, the probability of harboring two or more clonally unrelated precancer fields is

Model Calibration

The microscopic tissue-level models were calibrated based on population-level incidence data. Using a computational Bayesian framework we determined the posterior distributions for the identifiable parameters λ, θ and γ. Based on the posterior distributions, we derived model-based predictions of field quantities at time of diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. F. Michor (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute) and Prof. R. Durrett (Duke University) for valuable feedback on model design and analysis.

Financial support: NIH R01-GM096190 (M.D. Ryser); SNSF P300P-154583 (M.D. Ryser); NSF CMMI-1362236 (K.Z. Leder); NSF DMS-1224362 (J. Foo); NSF DMS-1349724 (J. Foo).

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Leemans CR, Braakhuis BJ, Brakenhoff RH. The Molecular Biology of Head and Neck Cancer. Nature reviews Cancer. 2011;11:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2013. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marur S, D'Souza G, Westra WH, Forastiere AA. Hpv-Associated Head and Neck Cancer: A Virus-Related Cancer Epidemic. The Lancet Oncology. 2010;11:781–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70017-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Hernandez BY, Xiao W, Kim E, et al. Human Papillomavirus and Rising Oropharyngeal Cancer Incidence in the United States. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:4294–301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. Field Cancerization in Oral Stratified Squamous Epithelium; Clinical Implications of Multicentric Origin. Cancer. 1953;6:963–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195309)6:5<963::aid-cncr2820060515>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Califano J, van der Riet P, Westra W, Nawroz H, Clayman G, Piantadosi S, et al. Genetic Progression Model for Head and Neck Cancer: Implications for Field Cancerization. Cancer research. 1996;56:2488–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabor MP, Brakenhoff RH, van Houten VM, Kummer JA, Snel MH, Snijders PJ, et al. Persistence of Genetically Altered Fields in Head and Neck Cancer Patients: Biological and Clinical Implications. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2001;7:1523–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Houten VM, Tabor MP, van den Brekel MW, Kummer JA, Denkers F, Dijkstra J, et al. Mutated P53 as a Molecular Marker for the Diagnosis of Head and Neck Cancer. The Journal of pathology. 2002;198:476–86. doi: 10.1002/path.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tabor MP, Brakenhoff RH, Ruijter-Schippers HJ, Van Der Wal JE, Snow GB, Leemans CR, et al. Multiple Head and Neck Tumors Frequently Originate from a Single Preneoplastic Lesion. The American journal of pathology. 2002;161:1051–60. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64266-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braakhuis BJ, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, Leemans CR, Brakenhoff RH. A Genetic Explanation of Slaughter's Concept of Field Cancerization: Evidence and Clinical Implications. Cancer research. 2003;63:1727–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oliveira MVMd, Fraga CAdC, Pereira CS, Barros LO, Oliveira ES, Guimarães ALS, et al. Field Cancerization in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Immunohistochemical Expression of P53 and Ki67 Proteins: Clinicopathological Study. Rev clín pesq odontol(Impr) 2010;6:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poh CF, Zhang L, Anderson DW, Durham JS, Williams PM, Priddy RW, et al. Fluorescence Visualization Detection of Field Alterations in Tumor Margins of Oral Cancer Patients. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2006;12:6716–22. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heaphy CM, Griffith JK, Bisoffi M. Mammary Field Cancerization: Molecular Evidence and Clinical Importance. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2009;118:229–39. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0504-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nonn L, Ananthanarayanan V, Gann PH. Evidence for Field Cancerization of the Prostate. The Prostate. 2009;69:1470–9. doi: 10.1002/pros.20983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graham TA, McDonald SA, Wright NA. Field Cancerization in the Gi Tract. Future oncology. 2011;7:981–93. doi: 10.2217/fon.11.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Squier CA, Kremer MJ. Biology of Oral Mucosa and Esophagus. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 2001:7–15. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clayton E, Doupe DP, Klein AM, Winton DJ, Simons BD, Jones PH. A Single Type of Progenitor Cell Maintains Normal Epidermis. Nature. 2007;446:185–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doupe DP, Alcolea MP, Roshan A, Zhang G, Klein AM, Simons BD, et al. A Single Progenitor Population Switches Behavior to Maintain and Repair Esophageal Epithelium. Science. 2012;337:1091–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1218835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martincorena I, Roshan A, Gerstung M, Ellis P, Van Loo P, McLaren S, et al. Tumor Evolution. High Burden and Pervasive Positive Selection of Somatic Mutations in Normal Human Skin. Science. 2015;348:880–6. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa6806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sprouffske K, Pepper JW, Maley CC. Accurate Reconstruction of the Temporal Order of Mutations in Neoplastic Progression. Cancer prevention research. 2011;4:1135–44. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takeda T, Sugihara K, Hirayama Y, Hirano M, Tanuma JI, Semba I. Immunohistological Evaluation of Ki-67, P63, Ck19 and P53 Expression in Oral Epithelial Dysplasias. Journal of oral pathology & medicine : official publication of the International Association of Oral Pathologists and the American Academy of Oral Pathology. 2006;35:369–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kushner J, Bradley G, Jordan RC. Patterns of P53 and Ki-67 Protein Expression in Epithelial Dysplasia from the Floor of the Mouth. The Journal of pathology. 1997;183:418–23. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199712)183:4<418::AID-PATH946>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gale N, Zidar N, Poljak M, Cardesa A. Current Views and Perspectives on Classification of Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions of the Head and Neck. Head and neck pathology. 2014;8:16–23. doi: 10.1007/s12105-014-0530-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reed AL, Califano J, Cairns P, Westra WH, Jones RM, Koch W, et al. High Frequency of P16 (Cdkn2/Mts-1/Ink4a) Inactivation in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer research. 1996;56:3630–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smeets SJ, Braakhuis BJ, Abbas S, Snijders PJ, Ylstra B, van de Wiel MA, et al. Genome-Wide DNA Copy Number Alterations in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas with or without Oncogene-Expressing Human Papillomavirus. Oncogene. 2006;25:2558–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smeets SJ, van der Plas M, Schaaij-Visser TB, van Veen EA, van Meerloo J, Braakhuis BJ, et al. Immortalization of Oral Keratinocytes by Functional Inactivation of the P53 and Prb Pathways. International journal of cancer. 2011;128:1596–605. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durrett R, Moseley S. Spatial Moran Models I. Stochastic Tunneling in the Neutral Case The annals of applied probability : an official journal of the Institute of Mathematical Statistics. 2015;25:104–15. doi: 10.1214/13-AAP989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Durrett R, Foo J, Leder K. Spatial Moran Models, Ii: Cancer Initiation in Spatially Structured Tissue. Journal of mathematical biology. 2016;72:1369–400. doi: 10.1007/s00285-015-0912-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foo J, Leder K, Ryser MD. Multifocality and Recurrence Risk: A Quantitative Model of Field Cancerization. Journal of theoretical biology. 2014;355:170–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2014.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bramson M, Griffeath D. On the Williams-Bjerknes Tumor-Growth Model. 2. Math Proc Cambridge. 1980;88:339–57. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elrefaey S, Massaro MA, Chiocca S, Chiesa F, Ansarin M. Hpv in Oropharyngeal Cancer: The Basics to Know in Clinical Practice. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2014;34:299–309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Attner P, Du J, Nasman A, Hammarstedt L, Ramqvist T, Lindholm J, et al. The Role of Human Papillomavirus in the Increased Incidence of Base of Tongue Cancer. International journal of cancer. 2010;126:2879–84. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyle P, Macfarlane GJ, Blot WJ, Chiesa F, Lefebvre JL, Azul AM, et al. European School of Oncology Advisory Report to the European Commission for the Europe against Cancer Programme: Oral Carcinogenesis in Europe. European journal of cancer Part B, Oral oncology. 1995;31B:75–85. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(95)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hashibe M, Brennan P, Chuang SC, Boccia S, Castellsague X, Chen C, et al. Interaction between Tobacco and Alcohol Use and the Risk of Head and Neck Cancer: Pooled Analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. Cancer Epidem Biomar. 2009;18:541–50. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agaku IT, King BA, Dube SR Control CfD, Prevention. Current Cigarette Smoking among Adults—United States, 2005–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:29–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freedman KS, Nelson NM, Feldman LL. Smoking Initiation among Young Adults in the United States and Canada, 1998–2010: A Systematic Review. Preventing chronic disease. 2012;9:E05. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goel RK, Nelson MA. The Effectiveness of Anti-Smoking Legislation: A Review. J Econ Surv. 2006;20:325–55. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinstock YE, Alava I, 3rd, Dierks EJ. Pitfalls in Determining Head and Neck Surgical Margins. Oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics of North America. 2014;26:151–62. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varvares MA, Poti S, Kenyon B, Christopher K, Walker RJ. Surgical Margins and Primary Site Resection in Achieving Local Control in Oral Cancer Resections. The Laryngoscope. 2015;125:2298–307. doi: 10.1002/lary.25397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luebeck EG, Moolgavkar SH. Multistage Carcinogenesis and the Incidence of Colorectal Cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:15095–100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222118199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meza R, Jeon J, Moolgavkar SH, Luebeck EG. Age-Specific Incidence of Cancer: Phases, Transitions, and Biological Implications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:16284–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801151105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gallaher J, Babu A, Plevritis S, Anderson AR. Bridging Population and Tissue Scale Tumor Dynamics: A New Paradigm for Understanding Differences in Tumor Growth and Metastatic Disease. Cancer research. 2014;74:426–35. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luebeck EG, Curtius K, Jeon J, Hazelton WD. Impact of Tumor Progression on Cancer Incidence Curves. Cancer research. 2013;73:1086–96. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holmberg L, Garmo H, Granstrand B, Ringberg A, Arnesson LG, Sandelin K, et al. Absolute Risk Reductions for Local Recurrence after Postoperative Radiotherapy after Sector Resection for Ductal Carcinoma in Situ of the Breast. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:1247–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kong I, Narod S, Taylor C, Paszat L, Saskin R, Nofech-Moses S, et al. Age at Diagnosis Predicts Local Recurrence in Women Treated with Breast-Conserving Surgery and Postoperative Radiation Therapy for Ductal Carcinoma in Situ: A Population-Based Outcomes Analysis. Current Oncology. 2013;21:96–104. doi: 10.3747/co.21.1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.James BYM, Gross CP, Wilson LD, Smith BD. Nci Seer Public-Use Data: Applications and Limitations in Oncology Research. Oncology. 2009;23:288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brouwer AF, Eisenberg MC, Meza R. Age Effects and Temporal Trends in Hpv-Related and Hpv-Unrelated Oral Cancer in the United States: A Multistage Carcinogenesis Modeling Analysis. PloS one. 2016;11:e0151098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marron M, Boffetta P, Zhang ZF, Zaridze D, Wunsch-Filho V, Winn DM, et al. Cessation of Alcohol Drinking, Tobacco Smoking and the Reversal of Head and Neck Cancer Risk. International journal of epidemiology. 2010;39:182–96. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Armitage P, Doll R. The Age Distribution of Cancer and a Multi-Stage Theory of Carcinogenesis. British journal of cancer. 1954;8:1–12. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1954.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moolgavkar SH, Dewanji A, Venzon DJ. A Stochastic Two-Stage Model for Cancer Risk Assessment. I. The Hazard Function and the Probability of Tumor Risk analysis : an official publication of the Society for Risk Analysis. 1988;8:383–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1988.tb00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dewanji A, Venzon DJ, Moolgavkar SH. A Stochastic Two-Stage Model for Cancer Risk Assessment. Ii. The Number and Size of Premalignant Clones Risk analysis : an official publication of the Society for Risk Analysis. 1989;9:179–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1989.tb01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luebeck EG, Moolgavkar SH. Stochastic Analysis of Intermediate Lesions in Carcinogenesis Experiments. Risk analysis : an official publication of the Society for Risk Analysis. 1991;11:149–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1991.tb00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Curtius K, Hazelton WD, Jeon J, Luebeck EG. A Multiscale Model Evaluates Screening for Neoplasia in Barrett's Esophagus. PLoS computational biology. 2015;11:e1004272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beerenwinkel N, Antal T, Dingli D, Traulsen A, Kinzler KW, Velculescu VE, et al. Genetic Progression and the Waiting Time to Cancer. PLoS computational biology. 2007;3:e225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Foo J, Leder K, Michor F. Stochastic Dynamics of Cancer Initiation. Physical biology. 2011;8:015002. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/8/1/015002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.