Abstract

Precursor B acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL), the most common childhood malignancy, arises from an expansion of malignant B cell precursors in the bone marrow. Epidemiological studies suggest that infections or immune responses to infections may promote such an expansion and thus BCP-ALL development. Nevertheless, a specific pathogen responsible for this process has not been identified. BCP-ALL cells critically depend on interactions with the bone marrow microenvironment. The bone marrow is also home to memory T helper (Th) cells that have previously expanded during an immune response in the periphery. In secondary lymphoid organs, Th cells can interact with malignant cells of mature B cell origin, while such interactions between Th cells and malignant immature B cell in the bone marrow have not been described yet. Nevertheless, literature supports a model where Th cells—expanded during an infection in early childhood—migrate to the bone marrow and support BCP-ALL cells as they support normal B cells. Further research is required to mechanistically confirm this model and to elucidate the interaction pathways between leukemia cells and cells of the tumor microenvironment. As benefit, targeting these interactions could be included in current treatment regimens to increase therapeutic efficiency and to reduce relapses.

Keywords: Precursor B acute lymphoblastic leukemia, T helper cells, Microenvironment, Infections, Malignant T cell-B cell interaction

Introduction

Precursor B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL) is the most common childhood malignancy and represents the leading cause of cancer-related death in children and young adults [1]. BCP-ALL arises from a monoclonal or oligoclonal expansion of malignant B cell precursors in the bone marrow. The malignant cells are characterized by chromosomal alterations leading to the expression of mutant proteins that confer survival and proliferation advantages. Nevertheless, these genetic lesions are not sufficient for BCP-ALL development. This is suggested by the fact that precursor B cells carrying such characteristic mutations are frequently found in newborns but the prevalence of leukemia is approximately a hundredfold lower [2, 3]. Based on these observations, a two-step model was proposed according to which the leukemia-initiating genetic lesion occurs in utero, followed by an event that promotes expansion of the pre-leukemic clone and eventually leads to the emergence of leukemia. Multiple causes for such a second event have been suggested, and most probably several of them account for the eventual transition to leukemia. Interestingly, epidemiological studies provide evidence that infections or immune responses to infections may represent a major trigger for the leukemia pathogenesis.

In the late 1980s, Kinlen noted a temporal increase in childhood leukemia in several occasions where previously isolated populations mingled [4–8]. At the same time, Mel Greaves postulated a “delayed infection” hypothesis, according to which the development of leukemia is partly caused by an abnormal immune reaction to a common infectious agent [9]. Thereafter, several large studies reported that children who attended a playgroup during their first year of life showed a significant protection from childhood ALL [10, 11]. Thus, similar to the hygiene hypothesis in allergy and asthma, a delayed exposure to common pathogens in developed societies may lead to abnormal or dysregulated immune responses that promote growth of the leukemic clone [12]. Most recently, this model received mechanistic support by an elegant investigation showing that experimental mice predisposed for BCP-ALL development due to a PAX5 mutation only developed BCP-ALL upon transfer from specific pathogen-free (SPF) environment to an environment containing common pathogens [13].

Immune responses to pathogens are typically composed of concerted actions by several types of immune cells. T helper (Th) cells play a central role in orchestrating immune responses by instructing and activating other immune cells. B cells, for example, depend on interaction with Th cells for their survival, proliferation, differentiation to plasma cells, hypermutation, class-switch recombination, adhesion, and migration [14]. While central in a functional immune system, such Th cell-B cell interactions, however, can also contribute to the pathogenesis of lymphoma and leukemia.

Malignantly transformed B cells often retain their capacity to interact with Th cells. As a consequence, malignant B cells seem to profit from Th cell help similar to healthy B cells. Such interactions between Th cells and malignant B cells with untoward effects have been described for several cancers arising from mature B cells, the main targets of Th cells. In contrast, the interaction of Th cells with malignant immature B cells such as BCP-ALL cells has not been studied extensively. In this article, we review the literature concerning the role of Th cells in mature B cell malignancies and summarize data hinting at a role of Th cells in BCP-ALL, i.e., in immature B cells, all in the context of the theory of an infectious etiology of BCP-ALL.

Review

Role of the microenvironment in BCP-ALL

The tumor microenvironment plays a key role in supporting survival and expansion of cancer cells [15–17]. In BCP-ALL, a variety of bone marrow stromal cells are believed to support survival and proliferation of BCP-ALL cells [18–21] and to confer drug resistance leading to treatment failure or disease relapse [22, 23]. Mesenchymal stromal cells [24], bone marrow endothelial cells [25], osteoblasts [26], and adipocytes [27] have all been shown to interact with BCP-ALL cells in mechanisms involving both soluble factors like cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors [28–33] as well as cell membrane-bound molecules such as Galectin-3 [34] or VE-cadherin [35]. These crosstalks between leukemic cells and cells of the tumor microenvironment include signaling pathways such as Notch signaling [36] or the wnt pathway [37]. While the microenvironment supports leukemia cells, the leukemia cells, in turn, shape the microenvironment according to their own benefit [38–41]. As a consequence, the bone marrow of leukemia patients exhibits substantial alterations that lead to support of the malignant cells and to impaired hematopoiesis [42].

The bone marrow is also home to mature Th cells [43–45]. These Th cells are derived from a past immune response in the periphery, where they have expanded and subsequently migrated to the bone marrow in order to provide long-term memory allowing for raising a rapid memory response upon re-challenge [46–48]. In addition, these bone marrow Th cells play a crucial role in normal hematopoiesis through the secretion of cytokines and chemokines [49–51].

Involvement of Th cells in B cell malignancies

Physiological T cell help for B cells takes place in germinal centers in peripheral lymphoid organs, where follicular Th cells interact with mature antigen-stimulated B cells. This interaction involves membrane-bound molecules like CD40 on the B cells and CD40L on the Th cells but also soluble factors like cytokines, chemokines or B cell-activating factor (BAFF) and Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 (flt3) ligand. Besides providing a suitable environment for the interaction of Th cells and B cells, germinal centers are also the site where malignant transformation of B cells occurs most frequently. This has led to the hypothesis that Th cells may not only support normal germinal center B cells but also germinal center cell-derived malignant B cells. In fact, there is increasing evidence for supportive role of Th cells in mature B cell malignancies. Follicular lymphoma (FL) is a lymphoma of B cells residing in follicles of secondary lymph nodes. FL cells showed an increased survival when stimulated by CD40 crosslinking in vitro [52] as well as upon cognate interaction with CD4+ Th cells [53]. Support of FL cells by Th cells was also observed in vivo and seems to be mediated by follicular Th cell-derived CD40L and IL-4 [54]. Hodgkin lymphoma—another B cell malignancy presumably arising from germinal center B cells—is characterized by infiltration of Th cells. Even though the function of these infiltrating Th cells is unclear, the presence of certain Th cells subset has been correlated with reduced overall survival, suggesting that these infiltrating Th cells may support growth of the malignant B cells [55, 56].

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a malignancy of mature B cells, although the precise cell of origin is unclear [57]. CLL cells proliferate in pseudofollicles in secondary lymphoid organs and in the bone marrow, where they receive support from the microenvironment. Recently, we demonstrated that peripheral blood and lymph nodes of CLL patients contained memory Th cells that were specific for endogenous CLL antigens and were able to interact with CLL cells in an antigen-dependent manner [58, 59]. These Th cells had a Th1-like phenotype and supported autologous CLL cell proliferation in vitro and in murine xenograft experiments. Furthermore, interaction of CLL cells with autologous Th cells led to an upregulation of the risk marker CD38 in an interferon (IFN)-γ-dependent mechanism [60]. Thus, while the support of normal mature B cells is central for the generation of an adaptive immune response, the same interaction between Th cells and malignant B cells seems to promote lymphoma or leukemia derived from malignantly transformed mature B cells.

A supportive role for Th cells in BCP-ALL?

Unlike the above-mentioned B cell malignancies that originate from mature B cells, BCP-ALL cells derive from precursor B cells, i.e., immature B cells. Surprisingly, little is known about the influence of Th cells on both normal and malignant precursor B cells in the bone marrow. Intriguingly, BCP-ALL cells as well as normal precursor B cells express all molecules required for cognate interaction with Th cells: CD40 [61], major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II, adhesion and co-stimulatory molecules [62, 63], and receptors for cytokines [64–71] and BAFF [72, 73]. Thus, they seem to have the capacity to present antigen to Th cells and receive support through the classical pathways.

In fact, BCP-ALL cells are receptive for CD40L stimulation, which generally has an activating effect on BCP-ALL cells, inducing proliferation [74] and upregulation of surface molecules like CD70 [75] and the receptor for IL-3 [76], a cytokine with proliferative function in BCP-ALL. In addition, CD40L stimulation was shown to induce secretion of chemoattractants [77] and to upregulate antigen-processing machinery components [78]. This suggests that BCP-ALL cells may attract Th cells and activate them through presentation of antigens, thereby inducing a positive feedback loop.

BCP-ALL cells can also respond to Th cell cytokines. While IL-2 has been found to stimulate proliferation [66], the Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 instead inhibited growth [74, 79–81], and IL-4 as well as TGF-β induced BCP-ALL cell apoptosis [82–84]. More recently, a proliferative effect of the cytokines IL-17 and IL-21 on BCP-ALL cells has been reported [85]. The observations that cytokines may be involved in the pathogenesis of BCP-ALL are consistent with the highly inflammatory environment in the bone marrow of leukemia patients [40].

Further support for the ability of BCP-ALL cells to react to soluble and membrane-bound Th cell factors comes from a report where stimulation with activated allogenic Th cells induced activation and maturation of BCP-ALL cells [86]. Interestingly, BCP-ALL is associated with certain MHC class II haplotypes. This may be a further hint that antigen presentation to Th cells is involved in BCP-ALL, even though mechanistic evidence is not available yet [87, 88].

Model for Th cell contribution to BCP-ALL

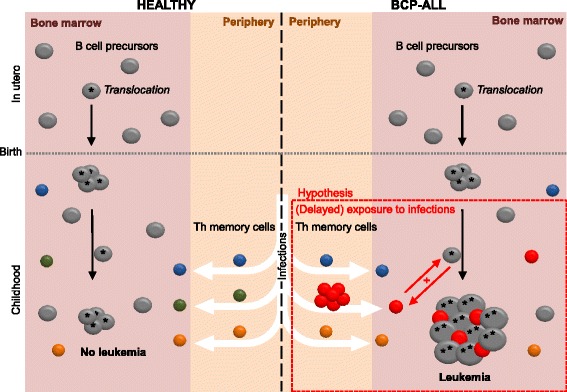

While epidemiological as well as experimental animal studies suggest that infections contribute to the pathogenesis of BCP-ALL, a specific infectious agent has not been identified. A strong association of BCP-ALL with viral infections such as chicken pox, rubella, measles, and influenza was described in British children [89], but no incorporation of microbial genetic information into host DNA could be detected when 20 BCP-ALL cases where analyzed by representational difference analysis [90]. This makes it unlikely that an infectious agent contributes to BCP-ALL by direct transformation of the precursor B cells. Even though pathogens may stimulate proliferation of precursor B cells or BCP-ALL cells through Toll-like receptors (TLR), this seems rather unlikely, since BCP-ALL cells home to the bone marrow, whereas most pathogens are encountered in the periphery. Instead, Th cells that have expanded during an immune response—possibly due to a delayed first exposure to pathogens—may aberrantly interact with and support the pre-leukemic or leukemic precursor B cells upon (Fig. 1). This interaction may be antigen-independent; alternatively, pathogen-specific Th cells might cross-react with endogenous antigen expressed and presented by the BCP-ALL cells. The nature of such endogenous antigens remains highly speculative and elusive. Attractive candidates are the fusion proteins generated by the characteristic chromosomal translocations, since they are likely to be recognized as foreign as no immune tolerance against these novel proteins has been induced. Indeed, Th cell clones against the fusion proteins TEL/AML1 and BCR/ABL could be generated in vitro [91, 92]. Nevertheless, it remains to be determined whether BCP-ALL patients actually carry such fusion protein-specific Th cells in their bone marrow as expanded clones, and whether these Th cells are able to interact with and support BCP-ALL cells.

Fig. 1.

Model integrating the infectious etiology hypothesis with the potential role of Th cells in BCP-ALL pathogenesis. Precursor B cells develop in the bone marrow, where they may undergo chromosomal rearrangements. Cells harboring such translocations that confer survival advantages are often present as expanded clones at birth, but this does not necessarily lead to leukemia development (left side). Infections in early childhood induce expansion of Th cells, which home to the bone marrow after the infection has been cleared to take part in normal hematopoiesis and to rise a memory response upon re-challenge with the pathogen (left side). Th cells expanded during an aberrant immune response due to delayed pathogen exposure may aberrantly interact with precursor B cells or leukemia cells or both after migration to the bone marrow, supporting their growth and survival, which ultimately leads to leukemia (right side)

In our work on CLL, we found that the CLL-specific Th cells recognized an antigenic peptide within the CLL B cell receptor (BCR) [58]. While not all subsets of BCP-ALL cells express surface pre-BCR, most express components of the pre-BCR intracellularly. Indeed, epitopes within the variable regions of the pre-BCR are apt candidates to engage Th cells, since they are likely to be presented on MHCII, and the Th cells are presumably not tolerant to these peptides. Still, both the antigen-dependence of the interactions between Th cells and BCP-ALL cells as well as the antigenic source remain speculations.

Implications for therapeutic approaches

Although modern treatment has reached an excellent rate of success in western world, treatment success in high-risk groups such as children with BCR-ABL or MLL-AF4 translocations remains poor. Furthermore, relapse occurs in about 20% of the patients, and the cure rate of a recurrent disease is significantly lower. Survivors often suffer from severe chronic health problems due to the toxic effects current therapy still has [93]. Therefore, there is justified need for biologically targeted therapeutic strategies with less side effects. The tumor microenvironment plays a central role in supporting tumor cell survival, proliferation, and drug resistance. As a consequence, effective leukemia therapies also ought to target the malignant crosstalk between leukemia cells and the supporting cells. Should the leukemia supporting role of Th cells be confirmed, it will be of great importance to elucidate the mechanisms underlying this malignant collaboration, since key molecules of this interaction may be targeted by future therapies. If the interaction of Th cells and BCP-ALL cells is antigen-specific, the BCP-ALL-supporting Th cells are likely to be oligoclonal. Thus, TCR-specific therapeutic antibodies could be generated and used to specifically deplete the leukemia-promoting Th cells, while Th cells with other specificities will remain functional. Although it will not be feasible to apply such a personalized therapy in the initial phase of the treatment, the approach may be combined with the existing drugs in the initial regimen in order to prevent drug resistance and relapse.

Conclusions

The link between BCP-ALL and infections in early childhood was proposed decades ago, but the pathological mechanisms remain unclear. A direct transformation of B cell precursors by pathogens seems unlikely. Instead, immune cells activated and expanded in response to those pathogens may supportively interact with B cell precursors and thereby promote leukemia. Due to their role in the immune system and their presence in the bone marrow, Th cells are good candidates for such leukemia-supportive immune cells. Indeed, it has been reported that BCP-ALL cells are receptive for soluble and membrane-bound Th cell stimuli. Nevertheless, it is to date unclear if BCP-ALL cells are able to receive help from autologous Th cells, and whether such a supportive interaction actually takes place in BCP-ALL patients’ bone marrow. The tumor microenvironment plays a key role in supporting malignant cells. As a consequence, efficient anti-cancer treatment should include targeting the cells of the microenvironment. Thus, identification and characterization of malignant collaboration between Th cells and BCP-ALL cells or their precursors may provide mechanistic support of the infectious etiology hypothesis and thereby open for novel therapies aiming to target the tumor microenvironment.

Acknowledgements

Simone Bürgler was supported by a grant of the Swiss cancer league (Krebsliga Schweiz, KLS-3189-02-2013) during the preparation of the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

SB and DN wrote the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- BAFF

B cell-activating factor

- BCP-ALL

Precursor B acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- FL

Follicular lymphoma

- IFN

Interferon

- MHC

Major histocompatibility complex

- Th

T helper

References

- 1.Pui CH, Robison LL, Look AT. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2008;371(9617):1030–1043. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford AM, Bennett CA, Price CM, Bruin MC, Van Wering ER, Greaves M. Fetal origins of the TEL-AML1 fusion gene in identical twins with leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(8):4584–4588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mori H, Colman SM, Xiao Z, Ford AM, Healy LE, Donaldson C, et al. Chromosome translocations and covert leukemic clones are generated during normal fetal development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(12):8242–8247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112218799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinlen L. Evidence for an infective cause of childhood leukaemia: comparison of a Scottish new town with nuclear reprocessing sites in Britain. Lancet. 1988;2(8624):1323–1327. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(88)90867-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinlen LJ, Clarke K, Hudson C. Evidence from population mixing in British New Towns 1946-85 of an infective basis for childhood leukaemia. Lancet. 1990;336(8715):577–582. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)93389-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinlen LJ. Epidemiological evidence for an infective basis in childhood leukaemia. Br J Cancer. 1995;71(1):1–5. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinlen LJ, Hudson C. Childhood leukaemia and poliomyelitis in relation to military encampments in England and Wales in the period of national military service, 1950-63. BMJ. 1991;303(6814):1357–1362. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6814.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinlen LJ, Balkwill A. Infective cause of childhood leukaemia and wartime population mixing in Orkney and Shetland, UK. Lancet. 2001;357(9259):858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greaves MF. Speculations on the cause of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 1988;2(2):120–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilham C, Peto J, Simpson J, Roman E, Eden TO, Greaves MF, et al. Day care in infancy and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: findings from UK case-control study. BMJ. 2005;330(7503):1294. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38428.521042.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma X, Buffler PA, Selvin S, Matthay KK, Wiencke JK, Wiemels JL, et al. Daycare attendance and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(9):1419–1424. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greaves M. Infection, immune responses and the aetiology of childhood leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(3):193–203. doi: 10.1038/nrc1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin-Lorenzo A, Hauer J, Vicente-Duenas C, Auer F, Gonzalez-Herrero I, Garcia-Ramirez I, et al. Infection exposure is a causal factor in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia as a result of Pax5-inherited susceptibility. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:1328–1343. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crotty S. A brief history of T cell help to B cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(3):185–189. doi: 10.1038/nri3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sison EA, Brown P. The bone marrow microenvironment and leukemia: biology and therapeutic targeting. Expert Rev Hematol. 2011;4(3):271–283. doi: 10.1586/ehm.11.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purizaca J, Meza I, Pelayo R. Early lymphoid development and microenvironmental cues in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Arch Med Res. 2012;43(2):89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayala F, Dewar R, Kieran M, Kalluri R. Contribution of bone microenvironment to leukemogenesis and leukemia progression. Leukemia. 2009;23(12):2233–2241. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manabe A, Coustan-Smith E, Behm FG, Raimondi SC, Campana D. Bone marrow-derived stromal cells prevent apoptotic cell death in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1992;79(9):2370–2377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manabe A, Murti KG, Coustan-Smith E, Kumagai M, Behm FG, Raimondi SC, et al. Adhesion-dependent survival of normal and leukemic human B lymphoblasts on bone marrow stromal cells. Blood. 1994;83(3):758–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mudry RE, Fortney JE, York T, Hall BM, Gibson LF. Stromal cells regulate survival of B-lineage leukemic cells during chemotherapy. Blood. 2000;96(5):1926–1932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradstock K, Bianchi A, Makrynikola V, Filshie R, Gottlieb D. Long-term survival and proliferation of precursor-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells on human bone marrow stroma. Leukemia. 1996;10(5):813–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tesfai Y, Ford J, Carter KW, Firth MJ, O’Leary RA, Gottardo NG, et al. Interactions between acute lymphoblastic leukemia and bone marrow stromal cells influence response to therapy. Leuk Res. 2012;36(3):299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duan CW, Shi J, Chen J, Wang B, Yu YH, Qin X, et al. Leukemia propagating cells rebuild an evolving niche in response to therapy. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(6):778–793. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwamoto S, Mihara K, Downing JR, Pui CH, Campana D. Mesenchymal cells regulate the response of acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells to asparaginase. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(4):1049–1057. doi: 10.1172/JCI30235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veiga JP, Costa LF, Sallan SE, Nadler LM, Cardoso AA. Leukemia-stimulated bone marrow endothelium promotes leukemia cell survival. Exp Hematol. 2006;34(5):610–621. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krevvata M, Silva BC, Manavalan JS, Galan-Diez M, Kode A, Matthews BG, et al. Inhibition of leukemia cell engraftment and disease progression in mice by osteoblasts. Blood. 2014;124(18):2834–2846. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-517219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ehsanipour EA, Sheng X, Behan JW, Wang X, Butturini A, Avramis VI, et al. Adipocytes cause leukemia cell resistance to L-asparaginase via release of glutamine. Cancer Res. 2013;73(10):2998–3006. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumagai M, Manabe A, Pui CH, Behm FG, Raimondi SC, Hancock ML, et al. Stroma-supported culture in childhood B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells predicts treatment outcome. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(3):755–760. doi: 10.1172/JCI118474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polak R, de Rooij B, Pieters R, den Boer ML. B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells use tunneling nanotubes to orchestrate their microenvironment. Blood. 2015;126(21):2404–2414. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-634238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Battula VL, Chen Y, Cabreira Mda G, Ruvolo V, Wang Z, Ma W, et al. Connective tissue growth factor regulates adipocyte differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells and facilitates leukemia bone marrow engraftment. Blood. 2013;122(3):357–366. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-437988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyerinas B, Zafrir M, Yesilkanal AE, Price TT, Hyjek EM, Sipkins DA. Adhesion to osteopontin in the bone marrow niche regulates lymphoblastic leukemia cell dormancy. Blood. 2013;121(24):4821–4831. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-475483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Juarez J, Baraz R, Gaundar S, Bradstock K, Bendall L. Interaction of interleukin-7 and interleukin-3 with the CXCL12-induced proliferation of B-cell progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2007;92(4):450–459. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fragoso R, Pereira T, Wu Y, Zhu Z, Cabecadas J, Dias S. VEGFR-1 (FLT-1) activation modulates acute lymphoblastic leukemia localization and survival within the bone marrow, determining the onset of extramedullary disease. Blood. 2006;107(4):1608–1616. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fei F, Joo EJ, Tarighat SS, Schiffer I, Paz H, Fabbri M, et al. B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia and stromal cells communicate through Galectin-3. Oncotarget. 2015;6(13):11378–11394. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Leary H, Akers SM, Piktel D, Walton C, Fortney JE, Martin KH, et al. VE-cadherin regulates Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia sensitivity to apoptosis. Cancer Microenviron. 2010;3(1):67–81. doi: 10.1007/s12307-010-0035-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nwabo Kamdje AH, Mosna F, Bifari F, Lisi V, Bassi G, Malpeli G, et al. Notch-3 and Notch-4 signaling rescue from apoptosis human B-ALL cells in contact with human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Blood. 2011;118(2):380–389. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-326694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Y, Mallampati S, Sun B, Zhang J, Kim SB, Lee JS, et al. Wnt pathway contributes to the protection by bone marrow stromal cells of acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells and is a potential therapeutic target. Cancer Lett. 2013;333(1):9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayani H. Composition and function of the hemopoietic microenvironment in human myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 1996;10(6):1041–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Vasconcellos JF, Laranjeira AB, Zanchin NI, Otubo R, Vaz TH, Cardoso AA, et al. Increased CCL2 and IL-8 in the bone marrow microenvironment in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(4):568–577. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vilchis-Ordonez A, Contreras-Quiroz A, Vadillo E, Dorantes-Acosta E, Reyes-Lopez A, del Quintela-Nunez Prado HM, et al. Bone marrow cells in acute lymphoblastic leukemia create a proinflammatory microenvironment influencing normal hematopoietic differentiation fates. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:386165. doi: 10.1155/2015/386165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Conforti A, Biagini S, Del Bufalo F, Sirleto P, Angioni A, Starc N, et al. Biological, functional and genetic characterization of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells from pediatric patients affected by acute lymphoblastic leukemia. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e76989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Colmone A, Amorim M, Pontier AL, Wang S, Jablonski E, Sipkins DA. Leukemic cells create bone marrow niches that disrupt the behavior of normal hematopoietic progenitor cells. Science. 2008;322(5909):1861–1865. doi: 10.1126/science.1164390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feuerer M, Beckhove P, Bai L, Solomayer EF, Bastert G, Diel IJ, et al. Therapy of human tumors in NOD/SCID mice with patient-derived reactivated memory T cells from bone marrow. Nat Med. 2001;7(4):452–458. doi: 10.1038/86523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dhodapkar MV, Krasovsky J, Osman K, Geller MD. Vigorous premalignancy-specific effector T cell response in the bone marrow of patients with monoclonal gammopathy. J Exp Med. 2003;198(11):1753–1757. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Herndler-Brandstetter D, Landgraf K, Jenewein B, Tzankov A, Brunauer R, Brunner S, et al. Human bone marrow hosts polyfunctional memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with close contact to IL-15-producing cells. J Immunol. 2011;186(12):6965–6971. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen L, Widhopf G, Huynh L, Rassenti L, Rai KR, Weiss A, et al. Expression of ZAP-70 is associated with increased B-cell receptor signaling in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2002;100(13):4609–4614. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tokoyoda K, Zehentmeier S, Hegazy AN, Albrecht I, Grun JR, Lohning M, et al. Professional memory CD4+ T lymphocytes preferentially reside and rest in the bone marrow. Immunity. 2009;30(5):721–730. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okhrimenko A, Grun JR, Westendorf K, Fang Z, Reinke S, von Roth P, et al. Human memory T cells from the bone marrow are resting and maintain long-lasting systemic memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(25):9229–9234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318731111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaufman CL, Colson YL, Wren SM, Watkins S, Simmons RL, Ildstad ST. Phenotypic characterization of a novel bone marrow-derived cell that facilitates engraftment of allogeneic bone marrow stem cells. Blood. 1994;84(8):2436–2446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ho VT, Soiffer RJ. The history and future of T-cell depletion as graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2001;98(12):3192–3204. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.12.3192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Monteiro JP, Benjamin A, Costa ES, Barcinski MA, Bonomo A. Normal hematopoiesis is maintained by activated bone marrow CD4+ T cells. Blood. 2005;105(4):1484–1491. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson PW, Watt SM, Betts DR, Davies D, Jordan S, Norton AJ, et al. Isolated follicular lymphoma cells are resistant to apoptosis and can be grown in vitro in the CD40/stromal cell system. Blood. 1993;82(6):1848–1857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Umetsu DT, Esserman L, Donlon TA, DeKruyff RH, Levy R. Induction of proliferation of human follicular (B type) lymphoma cells by cognate interaction with CD4+ T cell clones. J Immunol. 1990;144(7):2550–2557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pangault C, Ame-Thomas P, Ruminy P, Rossille D, Caron G, Baia M, et al. Follicular lymphoma cell niche: identification of a preeminent IL-4-dependent T(FH)-B cell axis. Leukemia. 2010;24(12):2080–2089. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alvaro T, Lejeune M, Salvado MT, Bosch R, Garcia JF, Jaen J, et al. Outcome in Hodgkin’s lymphoma can be predicted from the presence of accompanying cytotoxic and regulatory T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(4):1467–1473. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muenst S, Hoeller S, Dirnhofer S, Tzankov A. Increased programmed death-1+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in classical Hodgkin lymphoma substantiate reduced overall survival. Hum Pathol. 2009;40(12):1715–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chiorazzi N, Ferrarini M. Cellular origin(s) of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: cautionary notes and additional considerations and possibilities. Blood. 2011;117(6):1781–1791. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-155663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Os A, Burgler S, Ribes AP, Funderud A, Wang D, Thompson KM, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells are activated and proliferate in response to specific T helper cells. Cell Rep. 2013;4(3):566–577. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parente-Ribes A, Skanland SS, Burgler S, Os A, Wang D, Bogen B, et al. Spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitors reduce CD40L-induced proliferation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells but not normal B cells. Haematologica. 2016;101(2):e59–e62. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.135590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Burgler S, Gimeno A, Parente-Ribes A, Wang D, Os A, Devereux S, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells express CD38 in response to Th1 cell-derived IFN-gamma by a T-bet-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2015;194(2):827–835. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Law CL, Wormann B, LeBien TW. Analysis of expression and function of CD40 on normal and leukemic human B cell precursors. Leukemia. 1990;4(11):732–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mirkowska P, Hofmann A, Sedek L, Slamova L, Mejstrikova E, Szczepanski T, et al. Leukemia surfaceome analysis reveals new disease-associated features. Blood. 2013;121(25):e149–e159. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-468702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cardoso AA, Schultze JL, Boussiotis VA, Freeman GJ, Seamon MJ, Laszlo S, et al. Pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells may induce T-cell anergy to alloantigen. Blood. 1996;88(1):41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wormann B, Anderson JM, Ling ZD, LeBien TW. Structure/function analyses of IL-2 binding proteins on human B cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemias. Leukemia. 1987;1(9):660–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Inoue K, Sugiyama H, Ogawa H, Yamagami T, Azuma T, Oka Y, et al. Expression of the interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-6 receptor, and gp130 genes in acute leukemia. Blood. 1994;84(8):2672–2680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Touw I, Delwel R, Bolhuis R, van Zanen G, Lowenberg B. Common and pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells express interleukin 2 receptors, and interleukin 2 stimulates in vitro colony formation. Blood. 1985;66(3):556–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gu L, Zhou M, Jurickova I, Yeager AM, Kreitman RJ, Phillips CN, et al. Expression of interleukin-6 receptors by pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells with the t(4;11) translocation: a possible target for therapy with recombinant IL6-Pseudomonas exotoxin. Leukemia. 1997;11(10):1779–1786. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kebelmann-Betzing C, Korner G, Badiali L, Buchwald D, Moricke A, Korte A, et al. Characterization of cytokine, growth factor receptor, costimulatory and adhesion molecule expression patterns of bone marrow blasts in relapsed childhood B cell precursor all. Cytokine. 2001;13(1):39–50. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reid GS, Terrett L, Alessandri AJ, Grubb S, Stork L, Seibel N, et al. Altered patterns of T cell cytokine production induced by relapsed pre-B ALL cells. Leuk Res. 2003;27(12):1135–1142. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(03)00106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu S, Gessner R, von Stackelberg A, Kirchner R, Henze G, Seeger K. Cytokine/cytokine receptor gene expression in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: correlation of expression and clinical outcome at first disease recurrence. Cancer. 2005;103(5):1054–1063. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nakase K, Kita K, Miwa H, Nishii K, Shikami M, Tanaka I, et al. Clinical and prognostic significance of cytokine receptor expression in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: interleukin-2 receptor alpha-chain predicts a poor prognosis. Leukemia. 2007;21(2):326–332. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Parameswaran R, Muschen M, Kim YM, Groffen J, Heisterkamp N. A functional receptor for B-cell-activating factor is expressed on human acute lymphoblastic leukemias. Cancer Res. 2010;70(11):4346–4356. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Maia S, Pelletier M, Ding J, Hsu YM, Sallan SE, Rao SP, et al. Aberrant expression of functional BAFF-system receptors by malignant B-cell precursors impacts leukemia cell survival. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Planken EV, Dijkstra NH, Bakkus M, Willemze R, Kluin-Nelemans JC. Proliferation of precursor B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukaemia by activating the CD40 antigen. Br J Haematol. 1996;95(2):319–326. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Troeger A, Glouchkova L, Ackermann B, Escherich G, Hanenberg H, Janka G, et al. Significantly increased CD70 up regulation on TEL-AML positive B cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells following CD40 stimulation. Klin Padiatr. 2014;226:332–337. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1374640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhou M, Gu L, Holden J, Yeager AM, Findley HW. CD40 ligand upregulates expression of the IL-3 receptor and stimulates proliferation of B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells in the presence of IL-3. Leukemia. 2000;14(3):403–411. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ghia P, Transidico P, Veiga JP, Schaniel C, Sallusto F, Matsushima K, et al. Chemoattractants MDC and TARC are secreted by malignant B-cell precursors following CD40 ligation and support the migration of leukemia-specific T cells. Blood. 2001;98(3):533–540. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.3.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Luczynski W, Kowalczuk O, Ilendo E, Stasiak-Barmuta A, Krawczuk-Rybak M. Upregulation of antigen-processing machinery components at mRNA level in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells after CD40 stimulation. Ann Hematol. 2007;86(5):339–345. doi: 10.1007/s00277-007-0256-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Okabe M, Kuni-eda Y, Sugiwura T, Tanaka M, Miyagishima T, Saiki I, et al. Inhibitory effect of interleukin-4 on the in vitro growth of Ph1-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Blood. 1991;78(6):1574–1580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Consolini R, Legitimo A, Cattani M, Simi P, Mattii L, Petrini M, et al. The effect of cytokines, including IL4, IL7, stem cell factor, insulin-like growth factor on childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Res. 1997;21(8):753–761. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(97)00048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Renard N, Duvert V, Banchereau J, Saeland S. Interleukin-13 inhibits the proliferation of normal and leukemic human B-cell precursors. Blood. 1994;84(7):2253–2260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Manabe A, Coustan-Smith E, Kumagai M, Behm FG, Raimondi SC, Pui CH, et al. Interleukin-4 induces programmed cell death (apoptosis) in cases of high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1994;83(7):1731–1737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Buske C, Becker D, Feuring-Buske M, Hannig H, Wulf G, Schafer C, et al. TGF-beta inhibits growth and induces apoptosis in leukemic B cell precursors. Leukemia. 1997;11(3):386–392. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Buske C, Becker D, Feuring-Buske M, Hannig H, Griesinger F, Hiddemann W, et al. TGF-beta and its receptor complex in leukemic B-cell precursors. Exp Hematol. 1998;26(12):1155–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bi L, Wu J, Ye A, Wu J, Yu K, Zhang S, et al. Increased Th17 cells and IL-17A exist in patients with B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and promote proliferation and resistance to daunorubicin through activation of Akt signaling. J Transl Med. 2016;14(1):132. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-0894-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Renard N, Lafage-Pochitaloff M, Durand I, Duvert V, Coignet L, Banchereau J, et al. Demonstration of functional CD40 in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells in response to T-cell CD40 ligand. Blood. 1996;87(12):5162–5170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thompson P, Urayama K, Zheng J, Yang P, Ford M, Buffler P, et al. Differences in meiotic recombination rates in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia at an MHC class II hotspot close to disease associated haplotypes. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Taylor GM, Hussain A, Verhage V, Thompson PD, Fergusson WD, Watkins G, et al. Strong association of the HLA-DP6 supertype with childhood leukaemia is due to a single allele, DPB1*0601. Leukemia. 2009;23(5):863–869. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McKinney PA, Cartwright RA, Saiu JM, Mann JR, Stiller CA, Draper GJ, et al. The inter-regional epidemiological study of childhood cancer (IRESCC): a case control study of aetiological factors in leukaemia and lymphoma. Arch Dis Child. 1987;62(3):279–287. doi: 10.1136/adc.62.3.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.MacKenzie J, Greaves MF, Eden TO, Clayton RA, Perry J, Wilson KS, et al. The putative role of transforming viruses in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2006;91(2):240–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yun C, Senju S, Fujita H, Tsuji Y, Irie A, Matsushita S, et al. Augmentation of immune response by altered peptide ligands of the antigenic peptide in a human CD4+ T-cell clone reacting to TEL/AML1 fusion protein. Tissue Antigens. 1999;54(2):153–161. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.1999.540206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tanaka Y, Takahashi T, Nieda M, Masuda S, Kashiwase K, Ogawa S, et al. Generation of HLA-DRB1*1501-restricted p190 minor bcr-abl (e1a2)-specific CD4+ T lymphocytes. Br J Haematol. 2000;109(2):435–437. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]