Abstract

Objectives

Women in menopause have the more mood swings than before menopause. At the same time seem to sexual self-concept and sexual aspects of self-knowledge has a great impact on their mental health. This study aimed to investigate the sexual self-concept and its relationship to depression, stress and anxiety in postmenopausal women's.

Methods

In this descriptive correlation research, 300 of postmenopausal women referred to healthcare and medical treatment centers in Abadeh city were selected by convenience sampling method. The information in this study was collected by using questionnaires of multidimensional sexual self-concept and depression anxiety stress scale 21 (DASS-21). For data analysis, SPSS/17 software was used.

Results

The results showed the mean score positive sexual self-concept was 41.03 ± 8.66 and the average score of negative sexual self in women's was 110.32 ± 43.05. As well as scores of depression, stress, and anxiety, 35.67%, 32.33% and 37.67% respectively were in severe level. Positive and negative sexual self-concept scores with scores of stress, anxiety, and depression, of post-menopausal women in the confidence of 0.01, is significantly correlated (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

Being stress, anxiety, and depression in severe level and also a significant correlation between increased stress, anxiety and depression with negative and weak self-concept of women's, it is necessary to devote more careful attention to mental health issues of women's and have appropriate interventions.

Keywords: Anxiety; Depression; Menopause; Self-concept; Stress, psychological

Introduction

Menopause is considered one of the growth stages in the life cycle of women have a direct effect on quality of life and psychological well-being of women.1,2 So that postmenopausal women report a high level of complaints related to the mental health and poor performance of ovarian function such as depression, anxiety, stress, etc. Studies have shown that main reasons of this mood change is due to changes in levels of estradiol and relation of level of serum estrogen with the monoamine oxidase levels of platelets (Platelet MAO) which is a marker of adrenergic and serotonergic function.3,4

According to some studies, it is estimated that 26% of women will experience the first depression attack of their life during menopause. Several other studies also have shown that risk of depression increases during the transition to the menopausal periods.5 Mental health is considered as an important aspect of women's health and exposed to great stresses because of a particular social situation in the family and community.6 Stress can lead to the emergence and exacerbation of mental and physical symptoms such as depression and anxiety during the menopause.7 On the other hand, self-concept is called as one of the psychological factors affecting women. Each person has a self-image of himself or herself in his/her mind. In other words, self-concept is defined as overall assessment of person from his or her character. This assessment is due to the mental assessment of self which is usually carried out from behavioral characteristics. Sexual selfhood is one of the subjects that has been put at the focal attention of researchers in recent decades. The other interpretations of these terms include as follows: Sexual individuality and Sexual self-schema, Sexual subjecting and sexual self-perception.8,9

Sexual self-conception provides an understanding of each person's sexual aspects. Self-sexual means that how a person understand nature of his or her existence in sexual aspect. In other words, how a person thinks and feels about sexual matters in general.10 Also, self-sexual includes interpersonal and intrapersonal dimensions which requires understanding and assessing in two personal levels and also in the field of sexual experience with other person. The formation of self-sexual to person on the way of thinking to the sexual issues helps make decision on it and the way of interpretation of information received.11 Sexual self-conception is a part of individuality or self-sexual. In other words, one's perception of his or her sexual orientation and tendencies is the same sexual self-concept. Sexual self-concept will be shaped during social and psychological development process such as menopause consistent with gender stereotypes of each person. This psychological phenomenon is a factor to facilitate awareness, recognition and self-assessment of each person from nature of his or her sex life.12 Various studies have shown that high levels of stress, anxiety and depression can have negative effects on women's sexual self-concept in menopause stage.13 Health and mental health is one of social needs, because, favorable performance of society requires enjoying individuals who are in good condition in terms of mental health and health. Accordingly, trying to promote level of well-being in society is one of the objectives and programs of social systems.14

Therefore, the present study aimed to plan preventive programs and promote health of society with the aim of assessing sexual self-concept and its relation with depression, stress and anxiety in postmenopausal women.

Materials and Methods

This study is of descriptive-correlational type which was conducted on 300 women, aged 45 to 60, who had referred to the healthcare and medical treatment centers (women clinics) in Abadeh city. Sample size, with considering the degree of confidence (95%) and ability test (80%) and assuming that the correlation coefficient between the variables in women is r = 0.25, was estimated at 300 persons who were selected using convenience sampling method. The data of this study were collected using multidimensional sexual self-concept questionnaire (MSSCQ) and depression anxiety stress scale 21 (DASS-21). MSSCQ was designed by Snell15 in 1995. It should be noted that MSSCQ is one of the most useful tools that is used in the psychological field for measuring people's perception of their sexual relationship.16 This questionnaire is an objective self-report tool that its Persian version includes 78 questions and 18 domains and is validated by Ziaei et al.10 in Iran in 2013. The questions of Likert scale are marked from zero (the phrase “not at all” does not apply in my case.) to four (“applies” in my case completely). Domain are classified into the larger domains named negative sexual self-concept, positive sexual self-concept and situational sexual self-concept.

Given the purpose of the present study, scores of two components of negative sexual self-concept and positive sexual self-concept were studied. In this tool, four phrases are marked I reversed form. Each domain is composed of 3 to 5 items. The items belonging to each domain have been distributed across the questionnaire. 18 domains of Persian sexual self-concept in two positive and negative self-concept include as follows: sexual anxiety, sexual self-efficacy, sexual knowledge and awareness, motivation to avoid risky sexual relations, sexual desire, sexual bravery and courage, sexual optimism, sexual self-blame, sexual monitoring and supervision, sexual motivation, management of sexual issue, sexual value and reputation, sexual satisfaction, sexual-individual patterns, fear of sexual relationship, prevention of sexual problems, sexual depression and internal control of sexual issues. In the meantime, positive self-concept dimension includes: sexual self-efficacy components, sexual awareness, motivation to avoid risky sexual relations, sexual desire, sexual monitoring and supervision, sexual bravery and courage, sexual optimism, sexual motivation, sexual validity and reliability, management of sexual issues, prevention of sexual problems and sexual satisfaction. On the other hand, negative self-concept includes as follows: sexual anxiety, self-blame in sexual problems, fear of sexual relationship, sexual depression, internal control of sexual issues and sexual-individual patterns. The minimum score min positive and negative self-concept dimension is zero and maximum score in positive self-concept is 176 and maximum score in negative self-concept is 64. The degree of reliability of this questionnaire in various aspects has been reported from 0.76 to 0.89.10 In the present study, the reliability degree of 18-category domain of questionnaire was calculated from 0.77 to 0.87 using Cronbach's Alpha Coefficient.

The DASS is a 42-item self-administered questionnaire designed to measure the magnitude of three negative emotional states: depression, anxiety, and stress. Internal consistency for each of the subscales of the 42-item and the 21-item versions of the questionnaire are typically high (e.g. Cronbach's alpha of 0.96-0.97 for DASS-Depression, 0.84-0.92 for DASS-Anxiety, and 0.90-0.95 for DASS-Stress).17,18,19

In the present study, these figures stand at 0.76, 0.78 and 0.80. The specifications of the research units include as follows: having no suspected or confirmed pregnancy, lack of using contraceptive pills or substituted hormone therapy, history of hysterectomy operation, having at least one year history of amenorrhea and/or follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) more than 30 pg/mL, having relative health and no history of chronic mental and physical diseases. After selecting the qualified and eligible units, researcher introduced herself to them and explained the main objective of this study. Then, questionnaires were handed to them after obtaining the written consent letter and ensuring them on safeguarding and protecting information mentioned in questionnaire. It should be noted that researcher personally read all questions for samples and registered responses without any manipulation in questionnaires. Sampling was continued up to the last stage of completion of the desired number. Collect information from samples (women referred to healthcare and medical treatment centers) during the period lasted 7 months. Analysis of raw data obtained in this study was performed in two parts descriptive and inferential using descriptive statistics method and Pearson correlation analysis and Multiple Regression method simultaneously, so that sexual self-concept dimensions (positive and negative self-concept) has been tested by Pearson correlation test with depression, stress and anxiety of women.

Results

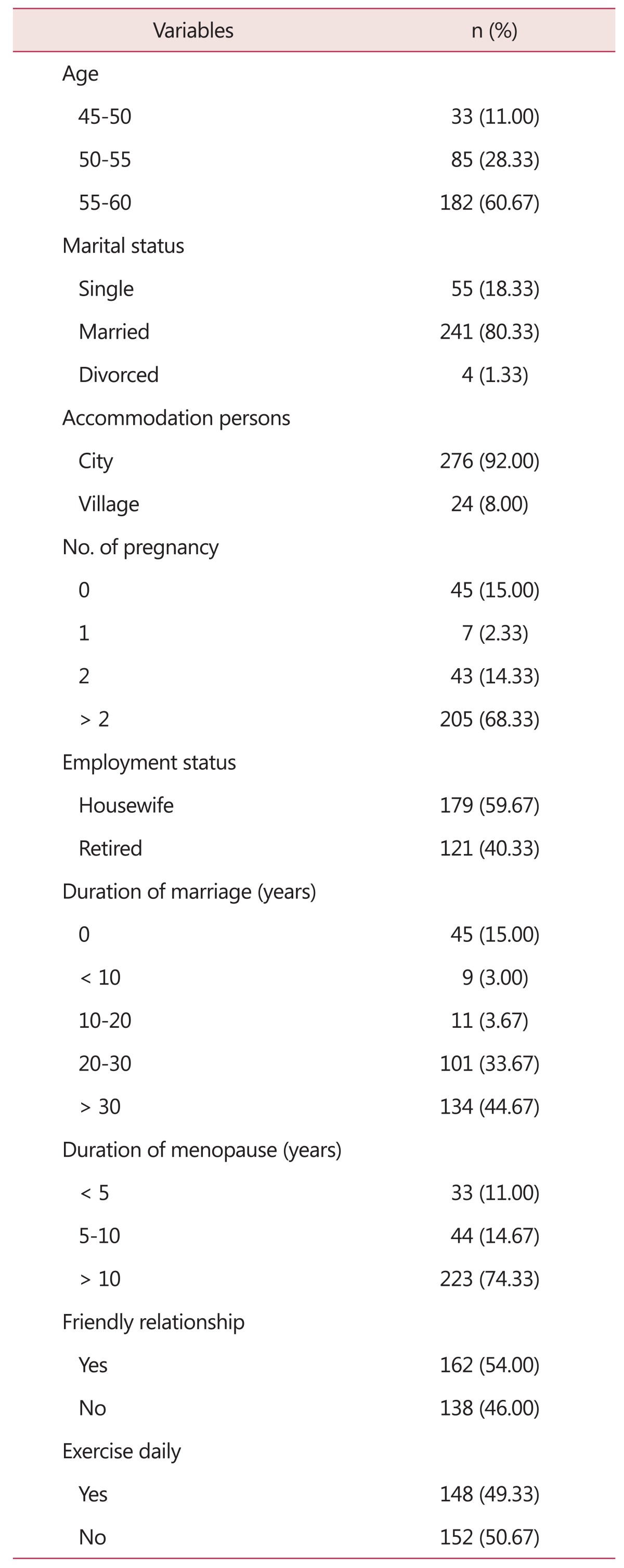

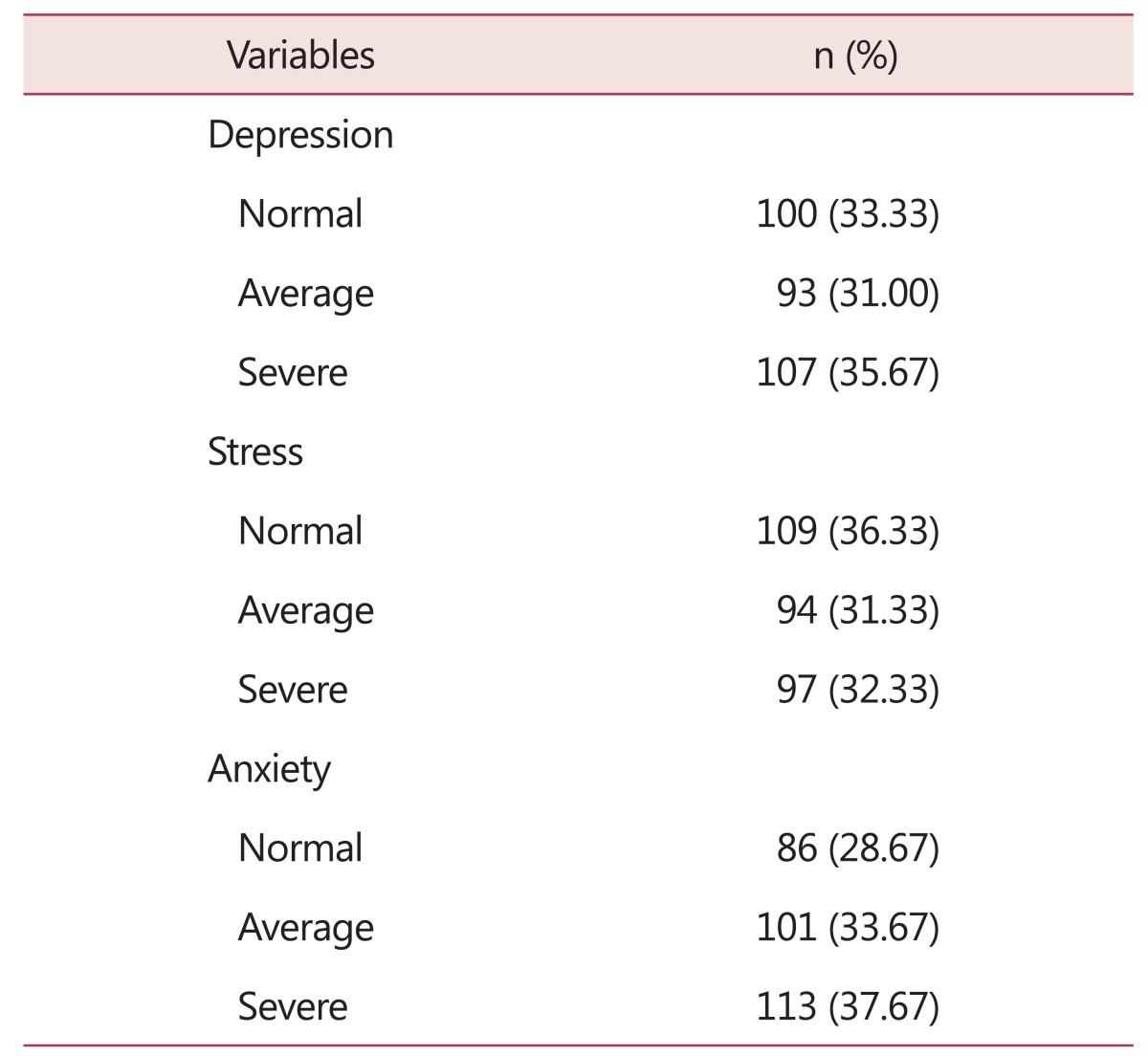

Of total 300 women who referred to Abadeh city healthcare and medical treatment centers, and participated in this plan, 45 (15%) and 241 (80.33%) of them were reported single and married respectively. Of total 300 women participated in this study, 121 of them (40.33%) had previous employment history. In other words, these women were reported retired. With due observance to the said issue, 179 of them (59.67%) were reported housewife. Demographic characteristics of postmenopausal women have been presented in Table 1. The results obtained in this study indicated that 200 women with depression (31% average depression and 35.67% severe depression) and 191 women with stress (31.33% average stress and 32.33% severe stress), 214 women with anxiety (33.67% average anxiety and 37.67% severe anxiety) (Table 2).

Table 1. Distribution of the participants.

Table 2. Prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression in menopausal women.

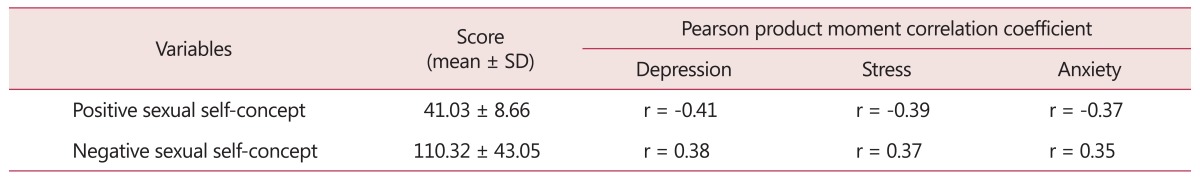

The average score of positive sexual self-concept stood at 41.03 ± 8.66 while the average score of negative sexual self-concept stood at 110.32 ± 43.05. Given the correlation matrix shown in Table 3, the positive and negative self-concept scores are significant correlation with the scores of depression, anxiety and stress of postmenopausal women in error level of 0.01 (P < 0.05).

Table 3. Results of Pearson product moment correlation coefficient sexual self-concept with depression, stress and anxiety.

The relationship between positive self-concept and depression, stress and anxiety in reversed form stand at r = -0.41, r = -0.39 and r = -0.37 respectively while the relationship between negative self-concept and depression, stress and anxiety in reversed form stood at r = 0.38, r = 0.37 and r = 0.35 respectively (Table 3). These results indicate that depression, stress and anxiety is reduced when the degree of positive sexual self-concept increases. In other words, the higher level of positive sexual self-concept, the reduced level of depression, stress and anxiety will be observed. Also, in line with negative self-concept relationship with the psychological factors, the results indicated that with increasing negative sexual self-concept, depression, stress and anxiety will also increase.

Discussion

The risk of stress, anxiety and depression in women is twice more than that of men, the issue of which will increase in certain period such as postmenopausal. Therefore, menopausal experience in women can be considered as a type of situational crisis.20,21

In the present study, the degree of depressed mood in severe level and outbreak of intense stress were reported 35.66% and 32.33% respectively. Also, 37.66% of women were reported with intense anxiety. Liu et al.22 in their study on menopausal women in China showed that dietary patterns that include a low intake of processed foods and/or a high intake of whole plant foods were associated with a reduced risk of depression and stress among Chinese postmenopausal women.

Radowicka et al.23 also are of the opinion that postmenopausal period in women is associated with an increase in psychiatric symptoms. In line with this study, de Kruif et al.24 in their study showed that mental health or physical mood such as depression and anxiety has direct impact on the level of stressful situation of menopause. Olchowska-Kotala25 also in his study in middle-aged women reported the same results consistent with the result of this study. Heidari and Ghodusi26 in their study, conducted on women with breast cancer, explained that physiological dimensions such as chronic, psychosocial and developmental diseases such as menopause are of the factors affecting the mental health of women in the process of life. Terauchi et al.27 in their study on depression and anxiety in postmenopausal women, reached to the contradictory and conflicting results. In their study, they reported that prevalence of psychological symptoms in postmenopausal women is not high in comparison with other women.

The reason of difference in results of the mentioned studies with the present study probably is related to the cultural differences among various communities in a way that women in some communities have been very patient and self-restraint. In most cases, these women do not complain of their pains and aches. In this study, it was specified that the average score of positive sexual self-concept stood at 41.03 ± 8.66 and negative sexual self-concept stood at 110.32 ± 43.05 respectively. In other words, the reported units obtained the maximum average score in negative sexual self-concept. The studies conducted in this respect showed that positive sexual self-concept is considered as one of the factors affecting individual's psychological dimensions.28 The results of studies conducted by Kwak et al.5 are consistent with the result of studied conducted by Kim and Lee3.

The results of Pearson Correlation Analysis showed that positive and negative sexual self-concept significant correlation with the scores of depression, anxiety and stress in postmenopausal women. Sexual self-concept is expressing the emotions, perceptions and beliefs that people have about their sexuality and regulate their behavior according to these feelings, emotions, perceptions.11

The results of the present study showed that there is a significant relationship between positive sexual self-concept and reduced mental symptoms. In other words, positive sexual self-concept in person will lead to desirable mental health and existence of negative sexual self-concept will lead to the mental symptoms. This means that positive sexual desire should exist in person in order to show depression, anxiety and stress negligible. When a person had positive feelings, beliefs and perceptions on his or her sexual relationship and in a broadly speaking, if a person had a positive attitude towards his or her sexual performance, this person will be healthier psychologically and mentally.29

This finding is consistent with the results of research conducted by Shifren and Avis30. In their study, they showed that sexual self-concept and psychological aspects in postmenopausal women are affected with each other.30 The weakness and negativity of self-concept in this study and other similar studies can be attributed to their psychological problems. Many psychologists believe that a positive self-concept in individuals will cause reduced psychological problems such as stress, anxiety and depression in them.31

Also, the results obtained from the study conducted by Zahiroddin et al.32 is consistent with the result of this study and confirms this issue that increased psychological problems (stress, anxiety and depression) in individuals such as menopause women will cause negativity and weakness of their self-concept.

One of the limitations of this study can be outlines to measure psychological variables of postmenopausal women using self-reporting methods. It is suggested that interview and clinical examination is used in order to detect psychological problems of this group of community along with self-reported tools.

Conclusion

The results showed that menopause, as a physiological process, can have a negative impact on psychological aspects of women and can cause depression, stress and anxiety in women. On the other hand, existence of positive sexual self-concept leads to better mental performance. Therefore, it can be concluded that identifying various sexual aspects in women at the stage of menopause and detecting and studying problems in each of areas of mental health by individuals with the help of counselors and psychologists can affect improvement of their quality of life positively.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Kim HK, Kang SY, Chung YJ, Kim JH, Kim MR. The recent review of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. J Menopausal Med. 2015;21:65–71. doi: 10.6118/jmm.2015.21.2.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shirvani M, Heidari M. Quality of life in postmenopausal female members and non-members of the elderly support association. J Menopausal Med. 2016;22:154–160. doi: 10.6118/jmm.2016.22.3.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim TH, Lee HH. Atlernative therapy trends among Korean postmenopausal women. J Menopausal Med. 2016;22:4–5. doi: 10.6118/jmm.2016.22.1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enkhbold T, Jadambaa Z, Kim TH. Management of menopausal symptoms in Mongolia. J Menopausal Med. 2016;22:55–58. doi: 10.6118/jmm.2016.22.2.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwak EK, Park HS, Kang NM. Menopause knowledge, attitude, symptom and management among midlife employed women. J Menopausal Med. 2014;20:118–125. doi: 10.6118/jmm.2014.20.3.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heidari M, Shahbazi S, Ghodusi M. Evaluation of body esteem and mental health in patients with breast cancer after mastectomy. J Midlife Health. 2015;6:173–177. doi: 10.4103/0976-7800.172345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim KY. The study of menopause-related quality of life and management of climacteric in a middle-aged female population in Korea. Public Health Wkly Rep. 2013;6:609–613. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esmail S, Darry K, Walter A, Knupp H. Attitudes and perceptions towards disability and sexuality. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:1148–1155. doi: 10.3109/09638280903419277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpentier MY, Fortenberry JD, Ott MA, Brames MJ, Einhorn LH. Perceptions of masculinity and self-image in adolescent and young adult testicular cancer survivors: implications for romantic and sexual relationships. Psychooncology. 2011;20:738–745. doi: 10.1002/pon.1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziaei T, Khoei EM, Salehi M, Farajzadegan Z. Psychometric properties of the Farsi version of modified Multidimensional Sexual Self-concept Questionnaire. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2013;18:439–445. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pai HC, Lee S, Yen WJ. The effect of sexual self-concept on sexual health behavioural intentions: a test of moderating mechanisms in early adolescent girls. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68:47–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinke EE, Wright DW, Chung ML, Moser DK. Sexual self-concept, anxiety, and self-efficacy predict sexual activity in heart failure and healthy elders. Heart Lung. 2008;37:323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sang JH, Kim TH, Kim SA. Flibanserin for treating hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Menopausal Med. 2016;22:9–13. doi: 10.6118/jmm.2016.22.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heidari M, Ghodusi M, Shahbazi S. Correlation between body esteem and hope in patients with breast cancer after mastectomy. J Clin Nurs Midwifery. 2015;4:8–15. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snell WE. The extended multidimensional sexuality questionnaire: measuring psychological tendencies associated with human sexuality; The annual meeting of the Southwestern Psychological Association; April; Houston, TX: Southwestern Psychological Association; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 16.La Rocque CL, Cioe J. An evaluation of the relationship between body image and sexual avoidance. J Sex Res. 2011;48:397–408. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2010.499522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:335–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Korotitsch W, Barlow DH. Psychometric properties of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:79–89. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Page AC, Hooke GR, Morrison DL. Psychometric properties of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) in depressed clinical samples. Br J Clin Psychol. 2007;46:283–297. doi: 10.1348/014466506X158996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mancheri H, Neyestanak NDS, Seyedfatemi N, Heydari M, Ghodoosi M. Psychosocial problems of families living with an addicted family member. Iran J Nurs. 2013;26:48–56. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Almeida OP, Marsh K, Murray K, Hickey M, Sim M, Ford A, et al. Reducing depression during the menopausal transition with health coaching: Results from the healthy menopausal transition randomised controlled trial. Maturitas. 2016;92:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu ZM, Ho SC, Xie YJ, Chen YJ, Chen YM, Chen B, et al. Associations between dietary patterns and psychological factors: a cross-sectional study among Chinese postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2016;23:1294–1302. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radowicka M, Szparaga R, Pietrzak B, Wielgos M. Quality of life in women after menopause. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2015;36:644–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Kruif M, Spijker AT, Molendijk ML. Depression during the perimenopause: A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;206:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olchowska-Kotala A. Psychological resources and self-rated health status on fifty-year-old women. J Menopausal Med. 2015;21:133–141. doi: 10.6118/jmm.2015.21.3.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heidari M, Ghodusi M. The relationship between body esteem and hope and mental health in breast cancer patients after mastectomy. Indian J Palliat Care. 2015;21:198–202. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.156500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terauchi M, Hiramitsu S, Akiyoshi M, Owa Y, Kato K, Obayashi S, et al. Associations between anxiety, depression and insomnia in peri- and post-menopausal women. Maturitas. 2012;72:61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarikhani R. Comparison of the effectiveness of sex education and traditional education on the trans-theoretical model-based model of sexual self nulliparous women after childbirth [master's thesis] Tehran, IR: University of Tehran; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woertman L, van den Brink F. Body image and female sexual functioning and behavior: a review. J Sex Res. 2012;49:184–211. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.658586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shifren JL, Avis NE. Surgical menopause: effects on psychological well-being and sexuality. Menopause. 2007;14:586–591. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318032c505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ybrandt H. The relation between self-concept and social functioning in adolescence. J Adolesc. 2008;31:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zahiroddin AR, Shafiee-Kandjani AR, Khalighi-Sigaroodi E. Do mental health and self-concept associate with rhinoplasty requests? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:1100–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]