ABSTRACT

The process of RNA replication by dengue virus is still not completely understood despite the significant progress made in the last few years. Stem-loop A (SLA), a part of the viral 5′ untranslated region (UTR), is critical for the initiation of dengue virus replication, but quantitative analysis of the interactions between the dengue virus polymerase NS5 and SLA in solution has not been performed. Here, we examine how solution conditions affect the size and shape of SLA and the formation of the NS5-SLA complex. We show that dengue virus NS5 binds SLA with a 1:1 stoichiometry and that the association reaction is primarily entropy driven. We also observe that the NS5-SLA interaction is influenced by the magnesium concentration in a complex manner. Binding is optimal with 1 mM MgCl2 but decreases with both lower and higher magnesium concentrations. Additionally, data from a competition assay between SLA and single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) indicate that SLA competes with ssRNA for the same binding site on the NS5 polymerase. SLA70 and SLA80, which contain the first 70 and 80 nucleotides (nt), respectively, bind NS5 with similar binding affinities. Dengue virus NS5 also binds SLAs from different serotypes, indicating that NS5 recognizes the overall shape of SLA as well as specific nucleotides.

IMPORTANCE Dengue virus is an important human pathogen responsible for dengue hemorrhagic fever, whose global incidence has increased dramatically over the last several decades. Despite the clear medical importance of dengue virus infection, the mechanism of viral replication, a process commonly targeted by antiviral therapeutics, is not well understood. In particular, stem-loop A (SLA) and stem-loop B (SLB) located in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) are critical for binding the viral polymerase NS5 to initiate minus-strand RNA synthesis. However, little is known regarding the kinetic and thermodynamic parameters driving these interactions. Here, we quantitatively examine the energetics of intrinsic affinities, characterize the stoichiometry of the complex of NS5 and SLA, and determine how solution conditions such as magnesium and sodium concentrations and temperature influence NS5-SLA interactions in solution. Quantitatively characterizing dengue virus NS5-SLA interactions will facilitate the design and assessment of antiviral therapeutics that target this essential step of the dengue virus life cycle.

KEYWORDS: NS5, RNA polymerase, dengue virus, stem-loop A

INTRODUCTION

Dengue virus (DENV) is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) virus and is a member of the Flavivirus genus within the Flaviviridae family. DENV causes a wide range of diseases in humans, ranging from self-limiting dengue fever to life-threatening dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome (1–5). Recent estimates indicate that more than 300 million dengue virus infections occur each year, 96 million of which clinically manifest. Currently, it is estimated that 3.9 billion people living in 128 countries are at risk of infection by DENV (6, 7). Four serotypes of the virus have been identified (DENV serotype 1 [DENV1] to DENV4), and most severe cases of hemorrhagic fever are associated with secondary infections by a serotype different from that of the first infection (8). The flavivirus genus also includes other human pathogens, such as West Nile virus, tick-borne encephalitis virus, yellow fever virus, and Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), as well as the rapidly spreading Zika virus.

The 11-kb DENV genome encodes 10 proteins, including three structural proteins (capsid, premembrane, and envelope proteins) and seven nonstructural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5) (9, 10). NS5 is a viral replicative RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) consisting of 900 amino acids distributed across two functional domains (11–14). The N-terminal methyltransferase (MTase) domain (263 amino acids long) functions as a guanylyltransferase and methyltransferase whose activity is necessary for 5′-RNA cap synthesis and methylation (15, 16); cap methylations are important for viral RNA recognition and for hijacking the host cell translational apparatus. The C-terminal domain possesses RdRp activity, including the active site for RNA synthesis. Crystal structures of DENV and JEV NS5 have been determined (17–19). These structures showed different interdomain interactions within the NS5 monomer and indicated that NS5 can adopt a number of conformations with different relative orientations of the MTase and RdRp domains. Additionally, interdomain interactions between monomers in an NS5 dimer suggest the coordination of RdRp and MTase activities across the NS5 monomer and dimer (17). Data from small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) studies indicate that NS5 proteins of all four DENV serotypes can adopt a more elongated shape than that in the crystal structure (20, 21), suggesting that flexibility between the MTase and RdRp domains is likely essential for the viral replication process. Interactions between the MTase and RdRp domains are also important for the polymerase activity of NS5, since full-length NS5 has higher polymerase activity than does the RdRp domain alone (22).

In addition to encoding viral proteins, the DENV genome contains tertiary RNA structures at the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) that regulate different viral processes (23). In particular, the 5′ UTR contains two stem-loops, stem-loop A (SLA) and stem-loop B (SLB), and SLA has been shown to function as a promoter for RNA synthesis during the replication process (24–26). The importance of SLA in viral RNA replication has been demonstrated for several flaviviruses (24, 27, 28). Despite the importance of SLA in initiating dengue virus RNA replication, interactions between NS5 and SLA have not been quantitatively analyzed, and thus, fundamental aspects of the NS5-SLA interaction, such as stoichiometry and energetics of intrinsic affinities, are unknown. We previously analyzed NS5 interactions with ssRNA and double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), as well as ssDNA and dsDNA, using fluorescence titration techniques (29). Here, we report studies of the interaction between NS5 and SLA and describe the effects of salt, magnesium, and temperature on NS5-SLA binding affinity. Moreover, a competition assay shows that SLA and ssRNA compete for the same binding site on NS5 polymerase and indicates that there is a 1:1 stoichiometry of NS5 to SLA in the NS5-SLA complex.

RESULTS

SLA80 forms a stable monomer in solution and adopts a more compact conformation with higher magnesium concentrations.

Flavivirus polymerase specifically recognizes the viral 5′ UTR during viral RNA replication (24, 25). In particular, SLA within the 5′ UTR is predicted to form a “Y”-shaped secondary structure and serves as a promoter for NS5 polymerase binding and activity (25, 27). Specific binding between NS5 and SLA was observed when SLA (70 nucleotides [nt]) had an additional ssRNA region at the 3′ end (Fig. 1) (25, 27). We thus constructed SLA with an additional 10 nt, containing the first 80 nt of the dengue virus genome, referred to here as SLA80, to study the interaction between SLA and NS5. We hypothesized that the stem-loop structure of SLA80 would be stabilized by cations that neutralize the negatively charged phosphate backbone, thus allowing close packing of the RNA. Therefore, we first determined the changes in the shape of SLA80 in the presence of Mg2+ by analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC). Sedimentation velocity AUC experiments measure the rate at which molecules move through solution and thus reflect hydrodynamic properties of macromolecules that are related to the size and shape of molecules. The size and shape of SLA80 were determined in the presence of 0, 1, and 10 mM MgCl2 (Table 1). The overall size and shape of the molecule were similar with both 0 and 1 mM MgCl2, with a Stokes radius of ∼3.5 nm, and low magnesium concentrations (1 mM) did not have any effect on the overall shape of the molecule. However, at 10 mM magnesium, SLA80 acquires a more compact shape, reflected in a ∼20% decrease in the Stokes radius from ∼3.5 nm to ∼2.7 nm. The frictional ratio also decreased from 1.8 to 1.6, indicating that SLA80 becomes more compact in the presence of 10 mM magnesium. The behavior of SLA80 in the presence of different concentrations of divalent cations is similar to those of previously studied structured RNAs such as the turnip yellow mosaic virus, tobacco mosaic virus, and brome mosaic virus RNAs, all of which become more compact at higher (10 mM) Mg2+ concentrations (30).

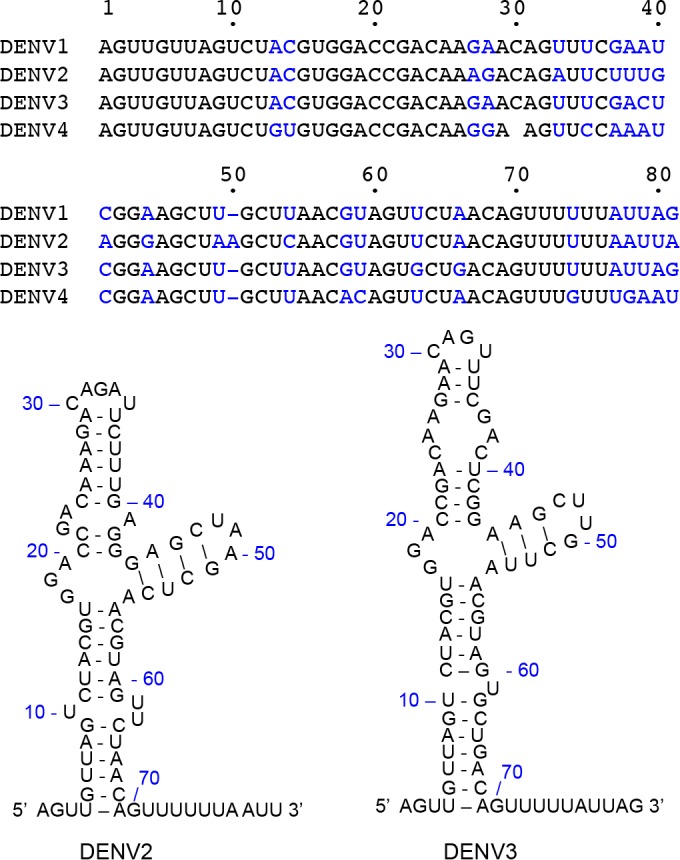

FIG 1.

Structure of SLA at the 5′ UTR of the DENV genome. The sequences for the first 80 nt from DENV1 to -4 genomes are shown, and nonconserved nucleotides are shown in blue. The secondary structures of DENV2 and DENV3 5′ UTRs were predicted by using the Mfold Web server (42).

TABLE 1.

Effect of magnesium on the size and shape of SLA80 as measured by AUC

| Mg concn (mM) | S20 | f/f0 | RH (nm)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2.17 | 1.8 | 3.53 |

| 1 | 2.14 | 1.8 | 3.51 |

| 10 | 2.32 | 1.6 | 2.74 |

RH, Stokes radius.

SLA80 binds specifically to DENV NS5.

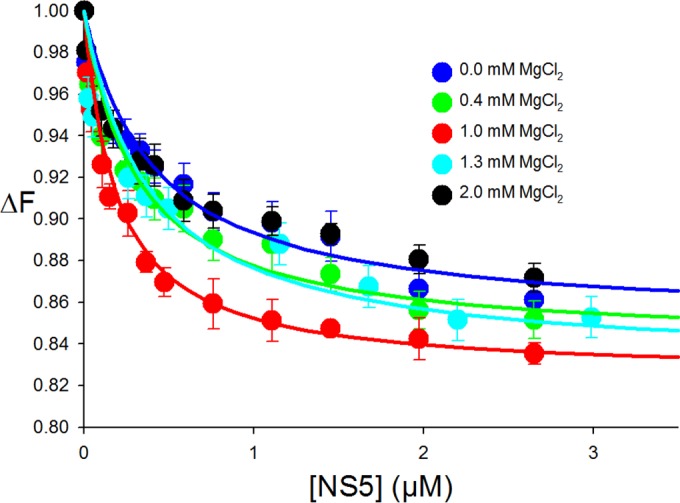

The binding constant for NS5 and SLA80 was determined by using SLA80 labeled with fluorescein at the 3′ end (SLA80-F) at 10°C. The dependence of the relative fluorescence intensity of SLA80-F (ΔFobs) on the NS5 concentration is shown in Fig. 2. Binding of NS5 to SLA80-F (1.5 × 10−8 M) in buffer B1 (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], and 10% glycerol) led to quenching of the marker emission intensity. The maximum observed value for fluorescence quenching is ∼17%. The titration curve was analyzed by using the approach described in Materials and Methods (equation 5). The nonlinear least-squares fit using K1 and ΔFmax as the only two fitting parameters provided a binding constant, K1, equal to 1.8 × 106 M−1 and thus a dissociation constant (Kd) of 0.55 μM (Fig. 2, blue circles).

FIG 2.

Interactions of fluorescein-labeled SLA80 with dengue virus NS5. Fluorescence titrations of fluorescein-labeled SLA80 with DENV3 NS5 (λex = 480 nm; λem = 520 nm) were carried out by using standard buffer (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 10% glycerol, and 1 mM DTT at 10°C) containing the following different MgCl2 concentrations: 0 mM, 0.4 mM, 1.0 mM, 1.3 mM, and 2.0 mM. The concentration of fluorescein-labeled SLA80 is 1.5 × 10−8 M. The solid lines are nonlinear least-squares fits of the titration curve with a K of 1.8 × 106 M−1 (0 mM MgCl2), a K of 2.2 × 106 M−1 (0.4 mM MgCl2), a K of 5.5 × 106 M−1 (1.0 mM MgCl2), a K of 2.3 × 106 M−1 (1.3 mM MgCl2), and a K of 1.8 × 106 M−1 (2.0 mM MgCl 2).

Next, we tested how the magnesium concentration affects the formation of the NS5-SLA80 complex, since previous binding studies of NS5 and ssRNA showed that magnesium affects the affinity of NS5 for ssRNA (29). Fluorescence titrations of SLA80-F with NS5 in buffer B1 containing 0, 0.4, 1.0, 1.3, and 2.0 mM MgCl2 at 10°C are shown in Fig. 2. An increase of the magnesium concentration from 0 to 1 mM enhanced the binding constant from a K0 mM Mg of 1.8 × 106 M−1 to a K1 mM Mg of 5.5 × 106 M−1 (Kd of 181 nM). However, a further increase to 2 mM MgCl2 did not enhance NS5-SLA80 affinity but rather reduced it to the value measured with 0 mM MgCl2. Furthermore, NS5-SLA80 interactions were not detectable at a higher magnesium concentration of 10 mM; i.e., no fluorescence change was observed upon the addition of NS5. SLA80 was shown to adopt a more compact conformation with 10 mM MgCl2 by AUC (Table 1), and thus, the compact form of SLA observed in the presence of 10 mM MgCl2 may not be able to bind NS5. Our results indicate that the optimal magnesium concentration for interactions between NS5 and SLA80 is ∼1 mM.

Effect of salt on NS5-SLA80 interactions.

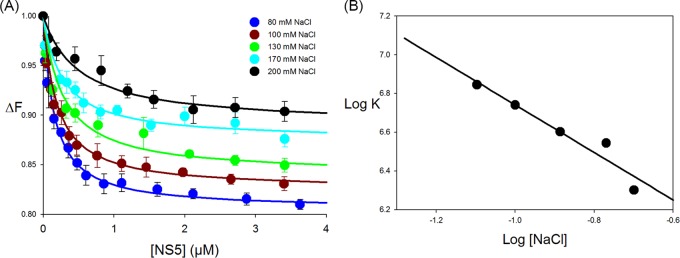

To determine the salt dependence of NS5 binding to SLA80, fluorescence titrations of SLA80-F with NS5 were carried out in buffer B1 containing 80, 100, 130, 170, and 200 mM NaCl and 1 mM MgCl2 at 10°C (Fig. 3A). As the salt concentration increased, the maximum fluorescence change at saturation, ΔFmax, decreased from ∼19% at 80 mM to ∼10% at 200 mM NaCl. The affinity of NS5 for SLA80 decreased with increasing salt concentrations, from a K of 7.0 × 106 M−1 (Kd of 142 nM) for 80 mM NaCl to a K of 2.0 × 106 M−1 (Kd of 500 nM) for 200 mM NaCl. The dependence of the logarithm of the intrinsic binding constant on the logarithm of [NaCl] (log-log plot) is shown in Fig. 3B (29, 31). This plot is linear in the studied salt concentration range, and the slope, ∂logK/∂log[NaCl], is −1.3, which indicates that the release of ∼1 Na+ ion accompanies the intrinsic interactions between NS5 and SLA80 (31).

FIG 3.

Effect of salt on SLA80-NS5 binding. (A) Fluorescence titrations of fluorescein-labeled SLA80 with NS5 (λex = 480 nm; λem = 520 nm) in buffer B1 (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5] at 10°C, 1 mM MgCl2) containing the following different NaCl concentrations: 80 mM, 100 mM, 130 mM, 170 mM, and 200 mM. The concentration of fluorescein-labeled SLA80 is 1.5 × 10−8 M. Increasing salt concentrations decrease the affinity of the polymerase for SLA80. The solid lines are nonlinear least-squares fits of the titration curve with a K of 7.0 × 106 M−1 (80 mM NaCl), a K of 5.5 × 106 M−1 (100 mM NaCl), a K of 4.0 × 106 M−1 (130 mM NaCl), a K of 3.5 × 106 M−1 (170 mM NaCl), and a K of 2.0 × 106 M−1 (200 mM NaCl). (B) Dependence of the logarithm of the intrinsic binding constant, K, on the logarithm of NaCl concentrations. The solid line is the linear least-squares fit of the NaCl concentration regions of the plot, which provide the slope, ∂logK/∂log[NaCl] = −1.3.

Effect of temperature on NS5-SLA80 interactions.

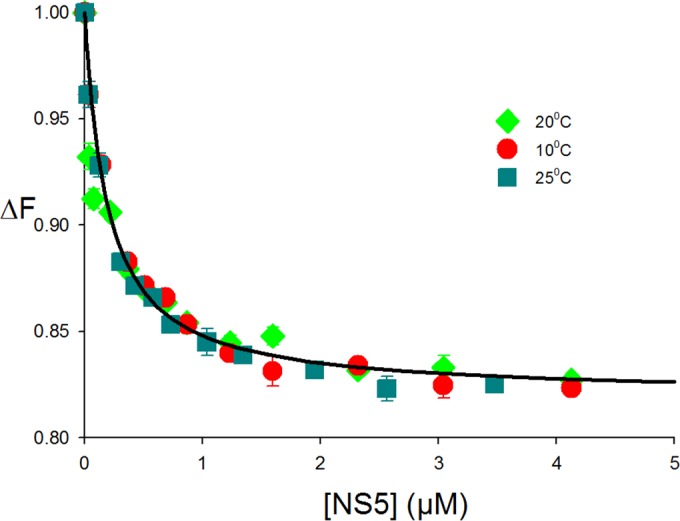

To further characterize the nature of the SLA80-NS5 interaction, we examined the effect of temperature on complex formation. Fluorescence titrations of SLA80-F with NS5 were performed in buffer B1 in the presence of 1 mM MgCl2 at 10, 20, and 25°C (Fig. 4). The titration curves were identical for all three temperatures, and nonlinear least-squares fitting, using equation 5 with K1 and ΔFmax as the only two fitting parameters, yielded a K value of 5.5 × 106 M−1 (Kd of 181 nM). Thus, neither the intrinsic affinity nor the value of ΔFmax is affected by temperature in the range from 10°C to 25°C. Thus, the interaction of NS5 with SLA80 is accompanied by an apparent enthalpy change, ΔH°, of ∼0. Hence, the intrinsic interactions are independent of temperature and are predominantly driven by the apparent entropy change, ΔS°.

FIG 4.

Effect of temperature on SLA80-NS5 binding. Shown are fluorescence titrations of fluorescein-labeled SLA80 with NS5 (λex = 480 nm; λem = 520 nm) in buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2) at 10, 20, and 25°C. The concentration of fluorescein-labeled SLA80 is 1.5 × 10−8 M. The solid line is a nonlinear least-squares fit of both titration curves with a K of 5.5 × 106 M−1.

SLA80 and single-stranded εA(pεA)19 compete for the same binding site on NS5.

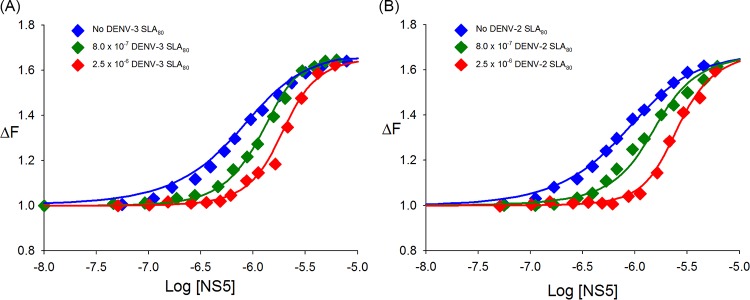

Although the DENV NS5 polymerase is known to specifically recognize SLA to initiate RNA replication, the SLA binding site on NS5 is not known. To determine whether the SLA binding site on NS5 overlaps the template binding site of the RdRp domain, direct competition studies of the binding of NS5 to the fluorescent etheno-adenosine 20-mer εA(pεA)19 were carried out in the presence of unlabeled SLA80. The etheno-derivative of A(pA)19, εA(pεA)19, was obtained by modification of A(pA)19 with chloroacetaldehyde (see Materials and Methods). Binding of NS5 to εA(pεA)19 enhanced the fluorescence emission intensity of the nucleic acid. The relative fluorescence signal (ΔFobs) of εA(pεA)19 (8.0 × 10−7 M) as a function of the logarithm of the NS5 concentration is shown in Fig. 5A (blue). The maximum relative change of the fluorescence signal is 68%. The binding of εA(pεA)19 to NS5 in the absence of SLA80 was analyzed by using equation 5 and yielded a KssRNA of 2.2 × 106 M−1. When DENV3 SLA80 (8.0 × 10−7 M) was present, the titration curve shifted toward higher NS5 concentrations, but the maximum value of the relative fluorescence signal remained unchanged (Fig. 5A, green). This result indicates competition between εA(pεA)19 and SLA80 for the same binding site on NS5. Analysis of the binding curve was performed by using equations 6 and 7 and yielded a KSLA80 of 7.0 × 106 M−1 (Kd of 142 nM).

FIG 5.

SLA80 and εA(pεA)19 compete for the same binding site on dengue virus NS5. (A) Fluorescence titrations of εA(pεA)19 with DENV3 NS5 (λex = 325 nm; λem = 410 nm) in standard buffer (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], and 10% glycerol at 10°C) in the absence and presence of DENV3 SLA80 at two concentrations, 8.0 × 10−7 M and 2.5 × 10−6 M. The concentration of εA(pεA)19 is 8.0 × 10−7 M. The solid lines are nonlinear least-squares fits of the titration curve with a K of 2.2 × 106 M−1 (no SLA80), a K of 7.0 × 106 M−1 (0.8 μM SLA80), and a K of 7.5 × 106 M−1 (2.5 μM SLA80). (B) Fluorescence titrations of εA(pεA)19 with DENV3 NS5 (λex = 325 nm; λem = 410 nm) in the absence and presence of DENV2 SLA80 at two concentrations, 8 × 10−7 M and 2.5 × 10−6 M. The solid lines are nonlinear least-squares fits of the titration curve with a K of 2.2 × 106 M−1 (no SLA80), a KSLA80 of 1.0 × 107 M−1 (0.8 μM SLA80), and a KSLA80 of 1.2 × 107 M−1 (2.5 μM SLA80).

At higher SLA80 concentrations {2.5 × 10−6 M [3-fold molar excess over εA(pεA)19]}, the titration curve was further shifted toward higher NS5 concentrations (Fig. 5A, red). Analysis of the binding reaction (equations 6 and 7) yielded a KSLA80 of 7.5 × 106 M−1 (Kd of 133 nM), the same as that obtained in the presence of 8.0 × 10−7 M SLA80 within experimental accuracy. Thus, the change of the SLA80 concentration did not affect the affinity of NS5 for SLA80, indicating that the 1:1 stoichiometry of the NS5-SLA80 complex remained unchanged.

SLAs at the 5′ end of the DENV1 to -4 genomes share between 75% (between DENV2 and DENV4) and 96% (between DENV1 and DENV3) sequence identities (Fig. 1). All SLA sequences are predicted to have a similar Y-shaped stem-loop structure (32). It was shown previously that DENV2 NS5 can use DENV1 SLA as a promoter to initiate RNA synthesis (32), suggesting that NS5 can bind SLA from different serotypes. We thus tested whether DENV3 NS5 binds DENV2 SLA80 using the competition titration assay described above. NS5-εA(pεA)19 complex formation was measured at two different concentrations of DENV2 SLA80, 8.0 × 10−7 and 2.5 × 10−6 M (Fig. 5B). Similar to the NS5 interaction with DENV3 SLA80 (Fig. 5A), the titration curves were shifted toward higher NS5 concentrations, indicating that DENV3 NS5 binds DENV2 SLA. DENV3 NS5 has a slightly higher affinity for DENV2 SLA80 than for its own serotype, with a KSLA80 of 1.0 × 107 M−1 (Kd of 100 nM with 8.0 × 10−7 SLA80). Further increasing the DENV2 SLA80 concentration to 2.5 × 10−6 M did not increase the binding constant (KSLA80 = 1.2 × 107 M−1; Kd of 83 nM), indicating that DENV3 NS5 interacts with DENV2 SLA with 1:1 stoichiometry. Therefore, DENV3 NS5 recognizes SLAs of other DENV serotypes and thus most likely can replicate the RNA genomes from other serotypes, consistent with data from previous reports (32).

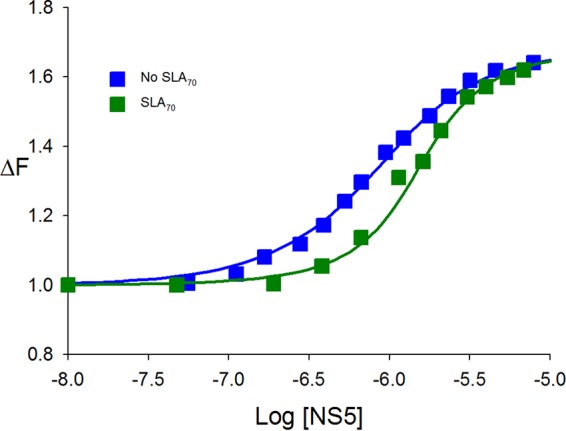

SLA70 binds specifically to full-length DENV NS5.

So far, we examined the interactions between NS5 and SLA80, which has the 10-nt ssRNA region at the 3′ end of SLA. To determine whether DENV NS5 recognizes SLA itself, we analyzed interactions between SLA70 (the stem-loop only) (Fig. 1) and the enzyme using a competition assay. The dependence of the relative fluorescence intensity of εA(pεA)19 (ΔFobs) on the logarithm of the NS5 concentration, in the absence and presence of SLA70, is shown in Fig. 6. The binding of NS5 to εA(pεA)19 in the absence of SLA70 has a KssRNA value of 2.2 × 106 M−1 (Fig. 6, blue squares). The presence of SLA70 clearly shifted the binding curve toward higher NS5 concentrations, while the maximum value of the relative fluorescence signal remained unchanged (Fig. 6, green squares). The nonlinear least-squares fit provided a KSLA70 of 1.2 × 107 M−1 (equations 6 and 7) and, thus, a Kd of 83 nM. This result indicates that SLA70 efficiently competes with εA(pεA)19 for the same binding site, and NS5 recognizes and binds to SLA70 as well as SLA80.

FIG 6.

SLA70 binds to full-length NS5. Shown are fluorescence titrations of εA(pεA)19 with DENV3 NS5 (λex = 325 nm; λem = 410 nm) in standard buffer (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], and 10% glycerol at 10°C) in the absence and presence of DENV3 SLA70. The concentration of εA(pεA)19 is 8.0 × 10−7 M. The solid lines are nonlinear least-squares fits of the titration curve with a K of 2.2 × 106 (no SLA70) and a KSLA70 of 1.2 × 107 M−1 (0.8 μM SLA70).

DISCUSSION

Replication of the viral genome is the primary goal of any viral infection, and thus obtaining quantitative information on the initial step of binding between NS5 and the RNA promoter is essential for understanding virus replication. We have characterized DENV3 NS5-SLA80 interactions under various solution conditions. DENV3 NS5 binds SLA80 with a dissociation constant of 130 to 140 nM, measured by either direct binding or competition assays (Fig. 2 and 5). The NS5-SLA80 interaction is affected by MgCl2 concentrations, and binding is strongest when the Mg2+ concentration is ∼1 mM. At higher Mg2+ concentrations (>1 mM), the affinity of NS5 for SLA80 is decreased. Further increases of Mg2+ concentrations to 10 mM, where SLA adopts a more compact form, diminish the polymerase affinity to hardly detectable levels in standard fluorescence titration experiments. This result suggests that there are two types of Mg2+ binding sites in the NS5-SLA80 complex, one that promotes the interaction between NS5 and SLA80 and the other that inhibits the interaction.

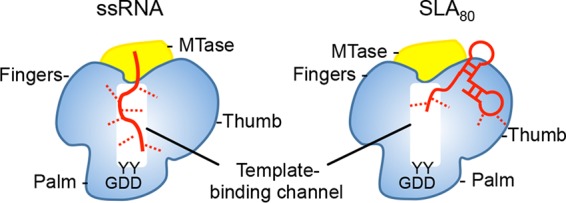

The NS5-SLA interaction is also influenced by the NaCl concentration, and ∼1 Na+ ion is released upon NS5-SLA80 complex formation (Fig. 3B). This result is in contrast to the NS5-ssRNA interaction, where the release of ∼6 Na+ ions during complex formation was observed (29). The weaker effect of NaCl observed for the NS5-SLA interaction indicates that the binding-site size (the numbers of nucleotides and amino acids involved in interactions) for SLA is smaller than that for ssRNA (Fig. 7). Unlike ssRNA, SLA acquires a defined structure, and thus, the data strongly suggest that SLA has a lower number of direct contacts with (but a higher affinity for) NS5 than does the ssRNA. Additionally, the NS5-SLA80 interaction is not influenced by temperature (Fig. 4), while the binding of NS5 and ssRNA is affected (29). The fact that the association reaction between NS5 and SLA80 is driven by entropy (Fig. 4) suggests that the interacting surfaces of the protein and SLA are not affected by complex formation; i.e., no additional structural adjustment is required as a result of complex formation, and the solvent and ions released from the complex drive the reaction.

FIG 7.

Model of the NS5-RNA interaction. NS5 consists of the MTase domain (yellow) and the RdRp domain (blue). The arrangement of the MTase and RdRp domains is depicted based on the crystal structures of DENV NS5 (PDB accession no. 5CCV). The template binding channel in RdRp is formed by the inner surfaces of the fingers and the thumb subdomains and leads to the active site in the palm subdomain (indicated by the GDD motif). An ssRNA binds in the template binding channel of NS5 with multiple interactions (left). The SLA70 or SLA80 binding site overlaps the template binding channel but involves less contact with NS5 than with ssRNA. The RNA molecules are shown in red, and interaction sites are depicted with dashed lines.

SLA is predicted to interact with NS5 via the RdRp domain, since full-length NS5 and the isolated RdRp domain can promote RNA synthesis and have similar binding affinities for SLA in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) (24, 25). However, it is not known where SLA binds on the RdRp domain. It seems unlikely that SLA binds in the template binding channel of RdRp, because crystal structures of NS5 and RdRp domains show a narrow template binding channel that is large enough to accommodate only an ssRNA. Competition assays between ssRNA (20-mer) and SLA80 showed that SLA80 competes with the ssRNA and that NS5 and SLA80 bind with a 1:1 stoichiometry (Fig. 5). This result indicates that the binding site for SLA80 on NS5 likely overlaps the template binding site in the RdRp domain, although direct contacts between the protein and the nucleic acid are likely different in the two complexes (Fig. 7). Recent studies of the interaction of DENV RdRp with the RNA genome suggest that the 3′ stem-loop is recognized by the thumb subdomain of RdRp, and the polymerase mutant that abolished the 3′ stem-loop interaction also eliminated 5′ SLA interactions (33). In the crystal structure of DENV NS5, the residues implicated in 3′ stem-loop/SLA binding in the thumb subdomain (R770, R773, R856, Y838, and K841) are exposed to the solvent and are away from the MTase domain. Thus, the proposed Arg-rich site in the thumb subdomain could be the SLA binding site in RdRp (Fig. 7).

DENV3 NS5 is able to bind DENV2 SLA80 with a slightly higher affinity (83 nM) than that for DENV3 SLA80 (Fig. 5). This affinity is slightly lower than the value reported for NS5 and SLA in the DENV2 system (10 to 20 nM), as measured by using EMSAs (24). Since DENV3 NS5 recognizes both DENV2 and DENV3 SLAs, the NS5 proteins likely recognize the fold and the sequence of SLA (Fig. 1). The DENV2 SLA regions important for NS5 binding and viral replication were previously identified (24, 25, 32). The base pairings at the bottom stem-loop (6UUA/65UAA and 12UAC/58GUA) (Fig. 1) and at the side stem-loop (44GAGC/51GCUC) are required for both NS5 binding and viral replication, whereas a disruption of base pairing at the top stem-loop (26AAG/36CUU) did not significantly affect NS5 binding or viral replication (21). The major difference between DENV2 and DENV3 SLA structures lies in the top stem-loop containing nt 22 to 41 (Fig. 1), which does not affect the association with NS5. Thus, DENV NS5 likely recognizes both DENV2 and -3 SLA80s, consistent with our results.

Furthermore, DENV NS5 binds SLA70 with an affinity similar to that determined for NS5-SLA80 binding (Fig. 6). The SLA70 construct encompasses the entire stem-loop but does not possess the additional 10 nucleotides at the 3′ end of SLA80. The ssRNA region at the 3′ end following SLA was shown to be required for the initiation of the polymerization reaction (25). The RdRp domain of NS5 does not bind to SLA without the ssRNA tail (i.e., SLA70) but binds SLA containing the 3′ ssRNA tail (such as SLA100) in EMSAs. Our results indicate that DENV3 NS5 binds both SLA70 and SLA80 with similar affinities, and thus, the NS5 polymerase recognizes the secondary structure and sequence of SLA, rather than the 10-nt ssRNA region at the 3′ end of SLA80. The reason for the discrepancy between data from previous studies and those from our studies could be due to different NS5 constructs (the RdRp domain versus full-length NS5), experimental methods (EMSA versus solution fluorescence), or the length of RNA used (100 nt versus 80 nt). Considering the similarities between the UTRs and NS5 sequences among all flaviviruses, our analysis of DENV3 NS5-SLA complex formation is likely applicable to other flaviviruses and should help in the development of antiviral therapeutics against flaviviral diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and buffers.

DENV3 SLAs (GenBank accession no. KU725665) containing the first 70 nucleotides (SLA70) and the first 80 nucleotides (SLA80) with and without a fluorescein tag at the 3′ end, DENV2 SLA80 (GenBank accession no. KU725663), and an adenosine 20-mer, A(pA)19, were synthesized (Midland Certified Reagents, Midland, TX). The concentrations of the nucleic acids were determined by using the following extinction coefficients: ϵ260 of 10,300 cm−1 M−1 for poly(A) and ϵ260 of 685,200 cm−1 M−1 for SLA. The etheno-derivative of A(pA)19, εA(pεA)19, was obtained by modification of A(pA)19 with chloroacetaldehyde. This modification goes to completion and provides a fluorescent derivative of the nucleic acid (29, 34, 35).

Expression and purification of DENV3 NS5.

Full-length DENV3 NS5 with a C-terminal hexahistidine tag was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21-CodonPlus-RIL cells (20). Briefly, the cells were grown at 37°C in Luria broth (LB) containing 34 μg/ml kanamycin and 30 mg/ml chloramphenicol to an absorbance at 600 nm of 0.6 to 0.7. The expression of the protein was induced by the addition of 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside. Cell growth was continued overnight at 18°C. For protein purification, the cells were suspended in lysis buffer (100 mM sodium phosphate [pH 8.0], 0.5 M NaCl, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 tablet of an EDTA-free protease inhibitor [Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany]) and sonicated. After centrifugation, the protein in the soluble fraction was purified by Talon metal affinity chromatography (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). NS5 was eluted with a 5 to 100 mM gradient of imidazole in 100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) buffer containing 0.5 M NaCl and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol. The fractions containing NS5 were collected and concentrated to 1 to 2 ml by using an Ultrafree centrifugal filter device (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Subsequently, the pooled fractions were loaded onto a Superdex 200 size exclusion column (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) equilibrated with a solution containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 0.4 M NaCl, and 2 mM DTT. DENV3 NS5 elutes as a monomer. The purity of the protein, estimated by SDS-PAGE, was >95%. The concentration of NS5 was spectrophotometrically determined with an extinction coefficient, ϵ280, of 21.2198 × 104 cm−1 M−1 obtained by using an approach based on the method of Edelhoch (36).

Fluorescence measurements.

Steady-state fluorescence titrations were performed by using an ISS PC1 spectrofluorometer (ISS, Urbana, IL). In order to avoid possible artifacts due to fluorescence anisotropy of the sample, polarizers were placed in excitation and emission channels and set at 90° and 55° (magic angle), respectively. The binding of DENV NS5 to the RNA was monitored by the fluorescence of either εA(pεA)19 (excitation wavelength [λex] = 325 nm; emission wavelength [λem] = 410 nm) or fluorescein attached to SLA80 (λex = 480 nm; λem = 520 nm). Binding curves were fit by using KaleidaGraph software (Synergy Software, PA). In the case of titrations using competition with εA(pεA)19, the relative increase in the fluorescence of the nucleic acid (ΔF) upon binding of DENV NS5 is defined as ΔFobs = (Fi − F0)/F0, where Fi is the fluorescence of the nucleic acid solution at a given titration point, i, and F0 is the initial fluorescence of the sample (29, 37–39). In the case of direct titrations of fluorescein-modified SLA, the relative fluorescence change is defined as Fi/F0. Both F0 and Fi are corrected for background fluorescence at the applied excitation wavelength (29, 37, 39). Standard B1 buffer, containing 50 mM Tris-HCl adjusted to pH 7.5 with HCl at a given temperature, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 10% (wt/vol) glycerol, was used for all binding experiments. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Fluorescence signal analysis.

The binding constant, K1, characterizing the association of SLA80 with NS5, is defined as

| (1) |

where [C1]F is the concentration of the formed complex.

The observed fluorescence of the sample at any point of the titration is defined as

| (2) |

where FF and FC are the molar fluorescence intensities of the free SLA80 and the formed complex, respectively. Thus,

| (3) |

The mass conservation equation for the total SLA80 concentration, [SLA80]T, in the sample is

| (4) |

Using equations 3 and 4, the relative observed change of the SLA80 fluorescence, ΔFobs, is then

| (5) |

where ΔFmax = FC/FF is the maximum value for the observed relative fluorescence quenching.

Competition assay.

Binding of εA(pεA)19 and NS5 was carried out in buffer B1 containing an additional 1 mM MgCl2 at 10°C by monitoring the changes of the fluorescence signal originating from εA(pεA)19 (λex = 325 nm; λem = 410 nm) (29). The binding constant was determined by using equation 5. In the competition assay, labeled εA(pεA)19 (each 8.0 × 10−7 M) and unlabeled SLA80 (8.0 × 10−7 M or 2.5 × 10−6 M) or SLA70 (8.0 × 10−7 M) were mixed in buffer B1 containing 1 mM MgCl2 and titrated with NS5 at 10°C. The change of the fluorescence signal originates only from the binding of εA(pεA)19 to the protein. The shift of the titration curve is a result of competition between εA(pεA)19 and either SLA80 or SLA70 for the binding site on NS5. Competition was analyzed by using equations 6 and 7, where K1 and K2 correspond to the binding constants characterizing the association of εA(pεA)19 with NS5 and the binding constant characterizing the association of SLA80 (or SLA70) with NS5, respectively (38). Experiments were repeated three times.

| (6) |

where the total NS5 concentration is

| (7) |

Analytical ultracentrifugation measurements.

The size and shape of SLA80 were analyzed by analytical ultracentrifugation using an Optima XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman Inc., Palo Alto, CA), as we described previously (29, 40, 41). Sedimentation equilibrium scans at different MgCl2 concentrations (0, 1, and 10 mM) were collected at the absorption band of SLA80 (260 nm). Time-derivative analyses of the sedimentation scans were performed with the software supplied by the manufacturer, using averages of 8 to 15 scans for each concentration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Luis Holthauzen for help with analytical ultracentrifugation and for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by NIH research grant R01 AI087856 (to K.H.C.) and a University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) Jeane B. Kempner postdoctoral scholar award (to P.J.B.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Chambers TJ, Hahn CS, Galler R, Rice CM. 1990. Flavivirus genome organization, expression, and replication. Annu Rev Microbiol 44:649–688. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.44.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blok J. 1985. Genetic relationships of the dengue virus serotypes. J Gen Virol 66(Part 6):1323–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westaway EG. 1987. Flavivirus replication strategy. Adv Virus Res 33:45–90. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60316-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guzmán MG, Kourí G. 2002. Dengue: an update. Lancet Infect Dis 2:33–42. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halstead SB. 2002. Dengue. Curr Opin Infect Dis 15:471–476. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200210000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, Drake JM, Brownstein JS, Hoen AG, Sankoh O, Myers MF, George DB, Jaenisch T, Wint GR, Simmons CP, Scott TW, Farrar JJ, Hay SI. 2013. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 496:504–507. doi: 10.1038/nature12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brady OJ, Gething PW, Bhatt S, Messina JP, Brownstein JS, Hoen AG, Moyes CL, Farlow AW, Scott TW, Hay SI. 2012. Refining the global spatial limits of dengue virus transmission by evidence-based consensus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6:e1760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guzmán MG, Alvarez M, Rodríguez R, Rosario D, Vázquez S, Valdes L, Cabrera MV, Kourí G. 1999. Fatal dengue hemorrhagic fever in Cuba, 1997. Int J Infect Dis 3:130–135. doi: 10.1016/S1201-9712(99)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klema VJ, Padmanabhan R, Choi KH. 2015. Flaviviral replication complex: coordination between RNA synthesis and 5′-RNA capping. Viruses 7:4640–4656. doi: 10.3390/v7082837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindenbach BD, Thiel H-J, Rice CM. 2007. Flaviviridae: the viruses and their replication, p 1101–1152. In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE (ed), Fields virology, 5th ed, vol 1 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yap TL, Xu T, Chen YL, Malet H, Egloff MP, Canard B, Vasudevan SG, Lescar J. 2007. Crystal structure of the dengue virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase catalytic domain at 1.85-angstrom resolution. J Virol 81:4753–4765. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02283-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrer-Orta C, Arias A, Escarmís C, Verdaguer N. 2006. A comparison of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases. Curr Opin Struct Biol 16:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi KH, Rossmann MG. 2009. RNA-dependent RNA polymerases from Flaviviridae. Curr Opin Struct Biol 19:746–751. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egloff MP, Benarroch D, Selisko B, Romette JL, Canard B. 2002. An RNA cap (nucleoside-2′-O-)-methyltransferase in the flavivirus RNA polymerase NS5: crystal structure and functional characterization. EMBO J 21:2757–2768. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Issur M, Geiss BJ, Bougie I, Picard-Jean F, Despins S, Mayette J, Hobdey SE, Bisaillon M. 2009. The flavivirus NS5 protein is a true RNA guanylyltransferase that catalyzes a two-step reaction to form the RNA cap structure. RNA 15:2340–2350. doi: 10.1261/rna.1609709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong H, Fink K, Zust R, Lim SP, Qin CF, Shi PY. 2014. Flavivirus RNA methylation. J Gen Virol 95:763–778. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.062208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klema VJ, Ye M, Hindupur A, Teramoto T, Gottipati K, Padmanabhan R, Choi KH. 2016. Dengue virus nonstructural protein 5 (NS5) assembles into a dimer with a unique methyltransferase and polymerase interface. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005451. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Y, Soh TS, Zheng J, Chan KW, Phoo WW, Lee CC, Tay MY, Swaminathan K, Cornvik TC, Lim SP, Shi PY, Lescar J, Vasudevan SG, Luo D. 2015. A crystal structure of the dengue virus NS5 protein reveals a novel inter-domain interface essential for protein flexibility and virus replication. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004682. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu G, Gong P. 2013. Crystal structure of the full-length Japanese encephalitis virus NS5 reveals a conserved methyltransferase-polymerase interface. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003549. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bussetta C, Choi KH. 2012. Dengue virus nonstructural protein 5 adopts multiple conformations in solution. Biochemistry 51:5921–5931. doi: 10.1021/bi300406n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saw WG, Tria G, Gruber A, Subramanian Manimekalai MS, Zhao Y, Chandramohan A, Srinivasan Anand G, Matsui T, Weiss TM, Vasudevan SG, Gruber G. 2015. Structural insight and flexible features of NS5 proteins from all four serotypes of dengue virus in solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 71:2309–2327. doi: 10.1107/S1399004715017721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Potisopon S, Priet S, Collet A, Decroly E, Canard B, Selisko B. 2014. The methyltransferase domain of dengue virus protein NS5 ensures efficient RNA synthesis initiation and elongation by the polymerase domain. Nucleic Acids Res 42:11642–11656. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gebhard LG, Filomatori CV, Gamarnik AV. 2011. Functional RNA elements in the dengue virus genome. Viruses 3:1739–1756. doi: 10.3390/v3091739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Filomatori CV, Lodeiro MF, Alvarez DE, Samsa MM, Pietrasanta L, Gamarnik AV. 2006. A 5′ RNA element promotes dengue virus RNA synthesis on a circular genome. Genes Dev 20:2238–2249. doi: 10.1101/gad.1444206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Filomatori CV, Iglesias NG, Villordo SM, Alvarez DE, Gamarnik AV. 2011. RNA sequences and structures required for the recruitment and activity of the dengue virus polymerase. J Biol Chem 286:6929–6939. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.162289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.You S, Padmanabhan R. 1999. A novel in vitro replication system for dengue virus. Initiation of RNA synthesis at the 3′-end of exogenous viral RNA templates requires 5′- and 3′-terminal complementary sequence motifs of the viral RNA. J Biol Chem 274:33714–33722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villordo SM, Carballeda JM, Filomatori CV, Gamarnik AV. 2016. RNA structure duplications and flavivirus host adaptation. Trends Microbiol 24:270–283. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang B, Dong H, Zhou Y, Shi PY. 2008. Genetic interactions among the West Nile virus methyltransferase, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, and the 5′ stem-loop of genomic RNA. J Virol 82:7047–7058. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00654-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szymanski MR, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski PJ, Bussetta C, Ye M, Choi KH, Bujalowski W. 2011. Full-length dengue virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase-RNA/DNA complexes: stoichiometries, intrinsic affinities, cooperativities, base, and conformational specificities. J Biol Chem 286:33095–33108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.255034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hammond JA, Rambo RP, Filbin ME, Kieft JS. 2009. Comparison and functional implications of the 3D architectures of viral tRNA-like structures. RNA 15:294–307. doi: 10.1261/rna.1360709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Record MT, Lohman ML, De Haseth P. 1976. Ion effects on ligand-nucleic acid interactions. J Mol Biol 107:145–158. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(76)80023-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lodeiro MF, Filomatori CV, Gamarnik AV. 2009. Structural and functional studies of the promoter element for dengue virus RNA replication. J Virol 83:993–1008. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01647-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hodge K, Tunghirun C, Kamkaew M, Limjindaporn T, Yenchitsomanus PT, Chimnaronk S. 2016. Identification of a conserved RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp)-RNA interface required for flaviviral replication. J Biol Chem 291:17437–17449. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.724013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tolman GL, Barrio JR, Leonard NJ. 1974. Chloroacetaldehyde-modified dinucleoside phosphates. Dynamic fluorescence quenching and quenching due to intramolecular complexation. Biochemistry 13:4869–4878. doi: 10.1021/bi00721a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gill SC, von Hippel PH. 1989. Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal Biochem 182:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edelhoch H. 1967. Spectroscopic determination of tryptophan and tyrosine in proteins. Biochemistry 6:1948–1954. doi: 10.1021/bi00859a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bujalowski W. 2006. Thermodynamic and kinetic methods of analyses of protein-nucleic acid. Chem Rev 106:556–606. doi: 10.1021/cr040462l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bujalowski PJ, Nicholls P, Oberhauser AF. 2014. UNC-45B chaperone: the role of its domains in the interaction with the myosin motor domain. Biophys J 107:654–661. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski PJ, Bujalowski W. 2007. Interactions of the DNA polymerase X from African swine fever virus with gapped DNA substrates. Quantitative analysis of functional structures of the formed complexes. Biochemistry 46:12909–12924. doi: 10.1021/bi700677j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gottipati K, Holthauzen LM, Ruggli N, Choi KH. 2016. Pestivirus Npro directly interacts with interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) monomer and dimer. J Virol 90:7740–7747. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00318-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marcinowicz A, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski PJ, Bujalowski W. 2007. Structure of the tertiary complex of the RepA hexameric helicase of plasmid RSF1010 with the ssDNA and nucleotide cofactors in solution. Biochemistry 46:13279–13296. doi: 10.1021/bi700729k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zuker M. 2003. Mfold Web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]