ABSTRACT

Outbreaks of respiratory virus infection at mass gatherings pose significant health risks to attendees, host communities, and ultimately the global population if they help facilitate viral emergence. However, little is known about the genetic diversity, evolution, and patterns of viral transmission during mass gatherings, particularly how much diversity is generated by in situ transmission compared to that imported from other locations. Here, we describe the genome-scale evolution of influenza A viruses sampled from the Hajj pilgrimages at Makkah during 2013 to 2015. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the diversity of influenza viruses at the Hajj pilgrimages was shaped by multiple introduction events, comprising multiple cocirculating lineages in each year, including those that have circulated in the Middle East and those whose origins likely lie on different continents. At the scale of individual hosts, the majority of minor variants resulted from de novo mutation, with only limited evidence of minor variant transmission or minor variants circulating at subconsensus level despite the likely identification of multiple transmission clusters. Together, these data highlight the complexity of influenza virus infection at the Hajj pilgrimages, reflecting a mix of global genetic diversity drawn from multiple sources combined with local transmission, and reemphasize the need for vigilant surveillance at mass gatherings.

IMPORTANCE Large population sizes and densities at mass gatherings such as the Hajj (Makkah, Saudi Arabia) can contribute to outbreaks of respiratory virus infection by providing local hot spots for transmission followed by spread to other localities. Using a genome-scale analysis, we show that the genetic diversity of influenza A viruses at the Hajj gatherings during 2013 to 2015 was largely shaped by the introduction of multiple viruses from diverse geographic regions, including the Middle East, with only little evidence of interhost virus transmission at the Hajj and seemingly limited spread of subconsensus mutational variants. The diversity of viruses at the Hajj pilgrimages highlights the potential for lineage cocirculation during mass gatherings, in turn fuelling segment reassortment and the emergence of novel variants, such that the continued surveillance of respiratory pathogens at mass gatherings should be a public health priority.

KEYWORDS: Hajj, epidemiology, evolution, influenza, phylogeny, transmission

INTRODUCTION

Mass gatherings (MGs) are occasions when large numbers of people come together to attend a specific event for a finite period of time, bringing with them the potential to strain the financial and medical resources of host communities (1–3). MGs vary greatly in nature and include music festivals, sporting events, and spiritual or religious gatherings. A unifying factor is that all result in an increased risk of outbreaks of communicable disease (4, 5). The nature of infectious disease outbreaks associated with specific events is dependent on the type, location, and timing of the gathering. For example, outbreaks associated with transmitted respiratory pathogens are more frequent when overcrowding is common and when the MG occurs in winter, with the influenza outbreak that took place during the 2008 World Youth Day in Sydney, Australia, an illustrative example (6). Similarly, a religious MG in Mexico (Passion Play of Iztapalapa) is believed to have accelerated the global transmission of the H1N1/09 subtype of influenza A virus (7). In contrast, MGs where sanitation is inadequate may result in outbreaks of fecal-oral pathogens, such as the infection of approximately 7,000 attendees of the Rainbow Family Gathering with Shigella sonnei in 1987 (8).

The Hajj, one of the largest annual MGs, sees between 2 and 3 million people from over 180 countries pilgrimage to Makkah (Mecca), Saudi Arabia (9). Throughout the Hajj, pilgrims take part in a series of rituals over 4 to 5 days, during which they reside in high-density tents, each housing up to 150 people (10). These rituals require large crowds to congregate in very confined spaces, with densities thought to reach up to seven individuals per square meter (11). This severe overcrowding results in elevated risks of airborne microbial transmission. For example, severe outbreaks of Neisseria meningitidis disease occurred at the Hajj gatherings in 1987 and 2000 (12, 13). Following the 2000 outbreak, more than 400 cases, originating from the strain circulating at the Hajj, were later reported from 16 countries in both infected pilgrims and their close contacts. The outbreak strain (serogroup W) was identified to have evolved from endemic strains circulating in Algeria, Mali, or Gambia in the 1990s (14). This outbreak highlighted the threat both to those attending MGs and to their home communities, calling attention to the potential risks of global dissemination of novel pathogens (15). Indeed, the prevalence of seasonal influenza at the Hajj is up to 4.5 times higher than that in the community (16).

To minimize the risks of communicable disease outbreaks and the potential for global dissemination of novel pathogens, it is important to understand the dynamics of infectious disease transmission within the closed environments of MGs. The hajj represents an ideal case study for the characterization of respiratory pathogens due to its high crowd densities and the geographic diversity of the pilgrims. While various studies have characterized the epidemiology of respiratory viral infections at the hajj (11, 17–22), we lack a precise understanding of the extent and structure of viral genetic diversity and virus transmission within a single MG, particularly the number of distinct introductions and their geographic origins and how virus genetic diversity, including that present within individual hosts, is reflected in and shaped by sequential transmission events. Using deep sequencing, we aimed to characterize the extent, origin, and drivers of the diversity of influenza A viruses at a genomic level within the setting of the hajj, including whether subconsensus mutations can be used to track individual transmission events.

RESULTS

Characterization of influenza viruses causing upper respiratory tract symptoms.

Of the 662 samples collected from pilgrims presenting with influenza-like illness (ILI) over the 3 years of study, only 31 were positive for influenza virus as tested by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR). Of those, 30 were determined to have influenza A virus (IAV) infections, and one participant was infected with influenza B virus (IBV) (Table 1). Of the 25 complete genomes characterized here, seven were subtyped as A(H1N1/09) and 18 were characterized as A(H3N2).

TABLE 1.

Influenza A subtype viruses and collection dates of samples from pilgrims presenting with ILI at the Hajj gatherings in 2013 to 2015

| Sample IDa | Collection date (mo/day-yr) | RT-PCR subtype | NGS subtypec | Pilgrim's country of origin | Putative transmission cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA/1/2013(H3) | 10/13/2013 | H3N2 | H3N2 | Saudi Arabia | |

| SA/2/2013(H1) | 10/15/2013 | H1N1 | H1N1 | Saudi Arabia | H1N1-2013 |

| SA/3/2013(H1)b | 10/15/2013 | H3N2 | H1N1 | Saudi Arabia | H1N1-2013 |

| SA/4/2013(H3) | 10/15/2013 | H3N2 | H3N2 | Saudi Arabia | H3N2-2013 |

| SA/5/2013(H3) | 10/15/2013 | H3N2 | H3N2 | Saudi Arabia | H3N2-2013 |

| AU/6/2014(H3) | 10/2/2014 | H3N2 | H3N2 | Australia | H3N2-2014 |

| AU/7/2014(H3) | 10/4/2014 | H3N2 | H3N2 | Australia | H3N2-2014 |

| SA/8/2014(H3) | 10/4/2014 | H3N2 | H3N2 | Saudi Arabia | |

| AU/9/2014(IBV) | 10/5/2014 | IBV | ND | Australia | |

| AU/10/2015(H1) | 09/22/2015 | H1N1 | UD | Australia | |

| AU/11/2015(H1) | 09/22/2015 | H1N1 | H1N1 | Australia | H1N1-2015b |

| AU/12/2015(H1) | 09/22/2015 | H1N1 | H1N1 | Australia | H1N1-2015a |

| AU/13/2015(H1) | 09/22/2015 | H1N1 | H1N1 | Australia | H1N1-2015a |

| SA/14/2015(H1) | 09/22/2015 | H1N1 | UD | Saudi Arabia | |

| AU/15/2015(H3) | 09/22/2015 | H3N2 | H3N2 | Australia | H3N2-2015c |

| AU/16/2015(H3) | 09/22/2015 | H3N2 | H3N2 | Australia | H3N2-2015b |

| AU/17/2015(H3) | 09/22/2015 | H3N2 | UD | Australia | |

| AU/18/2015(H3) | 09/22/2015 | H3N2 | H3N2 | Australia | |

| SA/19/2015(H3) | 09/22/2015 | H3N2 | H3N2 | Saudi Arabia | |

| SA/20/2015(H3) | 09/22/2015 | H3N2 | H3N2 | Saudi Arabia | H3N2-2015a |

| SA/21/2015(H1) | 09/25/2015 | H1N1 | UD | Saudi Arabia | |

| SA/22/2015(H1) | 09/25/2015 | H1N1 | H1N1 | Saudi Arabia | H1N1-2015b |

| SA/23/2015(H1) | 09/25/2015 | H1N1 | H1N1 | Saudi Arabia | H1N1-2015b |

| AU/24/2015(H3) | 09/25/2015 | H3N2 | H3N2 | Australia | H3N2-2015c |

| SA/25/2015(H3) | 09/25/2015 | H3N2 | H3N2 | Saudi Arabia | H3N2-2015b |

| SA/26/2015(H3) | 09/25/2015 | H3N2 | H3N2 | Saudi Arabia | |

| SA/27/2015(H3) | 09/25/2015 | H3N2 | H3N2 | Saudi Arabia | |

| SA/28/2015(H3) | 09/25/2015 | H3N2 | H3N2 | Saudi Arabia | H3N2-2015a |

| SA/29/2015(H3) | 09/25/2015 | H3N2 | H3N2 | Saudi Arabia | H3N2-2015a |

| SA/30/2015(H3) | 09/25/2015 | H3N2 | UD | Saudi Arabia | |

| SA/31/2015(H3) | 09/25/2015 | H3N2 | H3N2 | Saudi Arabia |

The sample identification number (ID) consists of the country of origin of the pilgrim/sample number/collection year (subtype).

Initially subtyped as A(H3N2) by RT-PCR but determined to be A(H1N1) by NGS.

ND, not done; UD, undetermined.

Diverse populations of influenza A virus circulate at the Hajj.

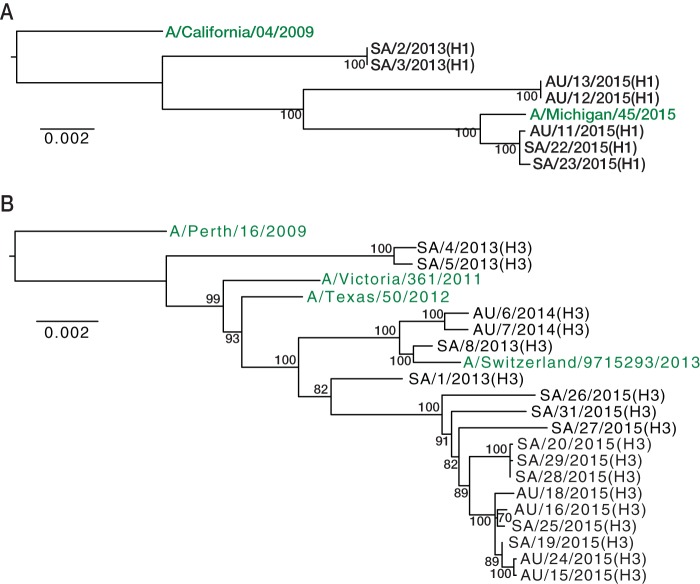

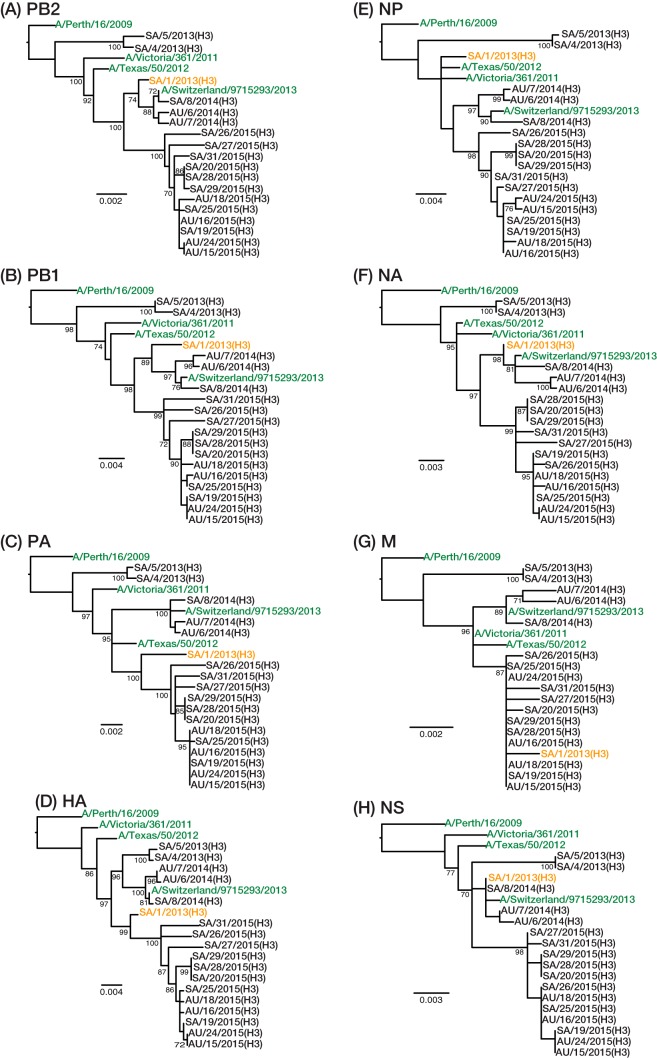

To determine the evolutionary relationships among our IAV samples, we first inferred phylogenetic trees from the consensus sequences of the concatenated coding genes. Analyzed separately, the A(H1N1) (Fig. 1A) and A(H3N2) (Fig. 1B) viruses clustered by collection year and formed monophyletic groups, within which well-supported subclusters could be identified. One exception was observed with the A(H3N2) viruses collected in 2013; these fell into two distinct lineages that represent the two dominant antigenic groups circulating globally in 2013, referred to as 3C.2 and 3C.3. Phylogenetic analysis of each gene segment individually identified one virus, SA/1/2013(H3) (indicating Saudi Arabia, sample 1, 2013 isolate, H3 subtype) sampled in 2013, with a likely history of reassortment [Fig. 2; segmental phylogenies for A(H1N1) are shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material]. Specifically, the PB2, PB1, NA, and NS gene segments were most closely related to a virus of the 3C.3 antigenic group, while the PA, hemagglutinin (HA), and M segments seemingly have their ancestry in viruses of the 3C.2 antigenic group. The origin of the nucleoprotein (NP) segment is less clear. However, there is no evidence that the reassortment event involving SA/1/2013(H3) occurred during the Hajj as obvious parental viruses could not be identified in the Hajj population.

FIG 1.

Phylogenetic trees of concatenated coding regions for A(H1N1) and A(H3N2) viruses. Publicly available vaccine strains were included as outgroups and are shown in green. For the viruses sampled at the Hajj pilgrimages, AU and SA denote Australia and Saudi Arabia (pilgrim's country of origin), respectively, the first digit indicates the sequence number, followed by the year of sampling (2013 to 2015), and the virus subtype is given in parentheses (H1 or H3). The A(H1N1) (A) and A(H3N2) (B) phylogenies were rooted using the A/California/04/2009 and A/Perth/16/2009 sequences, respectively. Statistical support for individual nodes was estimated from 1,000 bootstrap replicates, and values are represented as percentages on the nodes (values of >70% are shown). Scale bars are proportional to the number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

FIG 2.

Phylogenetic relationships of the PB2, PB1, PA, HA, NP, NA, M, and NS gene segments of A(H3N2) viruses, as indicated. A virus with a likely reassortant history, SA/1/2013(H3), is highlighted in orange, and publicly available vaccine strains were included as outgroups and are shown in green. Phylogenies were rooted using the A/Perth/16/2009 sequence. Statistical support for individual nodes was estimated from 1,000 bootstrap replicates, and values are represented as percentages on the nodes (values of >70% are shown). Scale bars are proportional to the number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

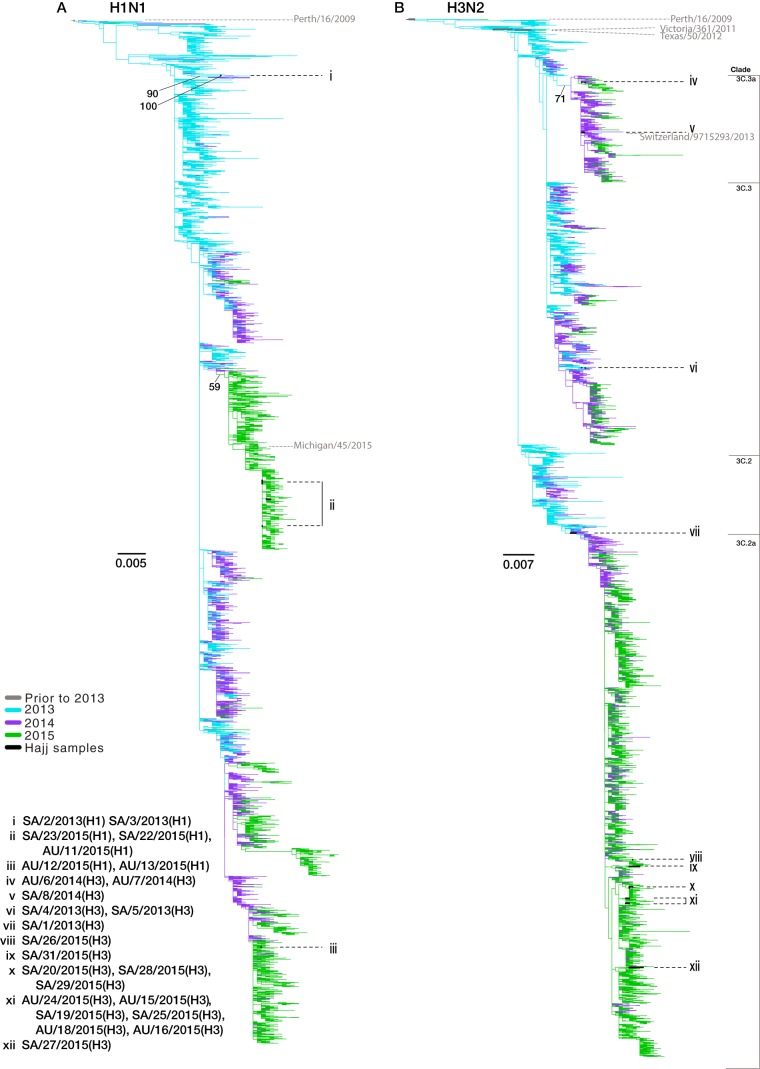

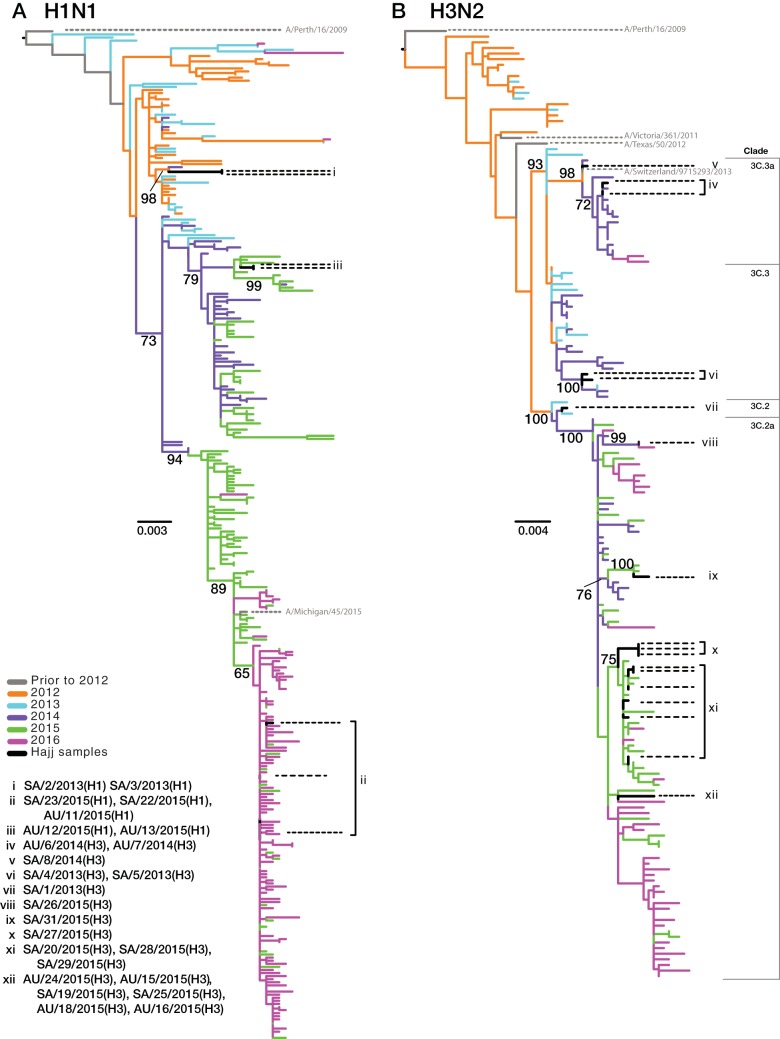

To place the Hajj strains within the context of global influenza virus genetic diversity and to determine the number of separate introductions into the Hajj population, we conducted a more expansive phylogenetic analysis using the (full-length) HA gene. Specifically, we compared the Hajj strains to those circulating globally (Fig. 3) and to only those strains circulating in Saudi Arabia and its neighboring countries (Fig. 4). Overall, these analyses revealed high levels of genetic diversity of both A(H1N1) and A(H3N2) viruses at the Hajj gatherings. Of note, the viruses from the Hajj gatherings were interspersed throughout the global diversity, suggesting that multiple A(H1N1) (Fig. 3A) and A(H3N2) (Fig. 3B) subtypes have been introduced each year (although bootstrap values were low across the tree); each proposed introduction is labeled as a group in Fig. 3 and 4. This was most apparent in 2015. Despite the small sample size in this year [n = 5 A(H1N1) viruses; n = 12 A(H3N2) viruses], we were able to infer that these viruses resulted from at least two introductions of A(H1N1) virus (Fig. 3A, groups ii and iii) and five introductions of A(H3N2) virus (Fig. 3B, groups viii, ix, x, xi, and xii).

FIG 3.

Phylogenetic trees of HA coding sequences for A(H1N1) and A(H3N2) viruses sampled globally from 2013 to 2015. All full-length HA coding gene sequences were downloaded from GenBank and GISAID, with duplicate sequences removed. The A(H1N1) (A) and A(H3N2) (B) phylogenies were rooted using the A/California/04/2009 and A/Perth/16/2009 sequences, respectively. Seasonal vaccine strains are labeled in gray, and antigenic groups are annotated. Branch colors represent the years of collection, and the Hajj samples are shown in black. Black dotted lines highlight the phylogenetic positions of samples collected from the Hajj pilgrimages, while proposed introduction events are labeled with Roman numerals (i to xii). Scale bars are proportional to the number of nucleotide substitutions per site. Bootstrap support values of >50% are shown for relevant nodes.

FIG 4.

Phylogenetic trees of the HA coding genes for A(H1N1) and A(H3N2) viruses circulating in Saudi Arabia and neighboring countries. Introductions are labeled as described in the legend of Fig. 2. The A(H1N1) (A) and A(H3N2) (B) phylogenies were rooted using A/California/04/2009 and A/Perth/16/2009 sequences, respectively. Seasonal vaccine strains are labeled in gray, and antigenic groups are annotated. Branch colors reflect the years of sample collection, and black represents viruses collected in this study. Black dotted lines highlight the phylogenetic positions of samples collected from the Hajj pilgrimages, while proposed introduction events are labeled with Roman numerals (i to xii). Scale bars are proportional to the number of nucleotide substitutions per site. Bootstrap support values of >60% are shown for relevant nodes.

We also used the collection date and sample origin of those strains most closely related to our Hajj viruses to investigate potential source localities for each introduction. This suggested that the 2015 A(H3N2) viruses were introduced from a variety of locations including both predominantly Muslim and non-Muslim countries. For example, the viruses most closely related to group viii, sampled prior to the 2015 Hajj, were from Mali, making Mali compatible as a potential source population (although the bootstrap value linking these sequences was only 64%). Similarly, these phylogenetic data are compatible with group ix originating in Cameroon (96% bootstrap support). In some cases the most closely related viruses appeared to circulate in diverse geographic regions; for example, group x clustered with multiple viruses isolated in Australia and North America, suggesting that it represents a globally dispersed lineage. Similarly, this phylogenetic approach suggested that the A(H1N1) group i may have been introduced from Europe as the closest sampled relatives of members of this group were from England and France (90% bootstrap support).

The A(H1N1) viruses sampled in 2015 fell into two distinct clades circulating in Saudi Arabia and neighboring countries, including Yemen, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Iran, Kuwait, Iraq, Jordan, Egypt, Sudan, and Eritrea (Fig. 4A). Group iii viruses were more closely related to viruses circulating in this region prior to the Hajj during the 2014-2015 Northern Hemisphere (NH) influenza season, while those viruses in group ii were more closely related to viruses circulating locally after the Hajj in the 2015-2016 NH influenza season.

Additionally, as was observed in our initial phylogenies, the 2013 A(H3N2) viruses again fell into the two antigenically divergent lineages, both of which circulated globally. From this more expansive analysis we were also able to determine that sample SA/1/2013(H3) (Fig. 4B, group vii) fell into a monophyletic group containing all the A(H3N2) viruses circulating at the Hajj in 2015. Interestingly, SA/1/2013(H3) belongs to HA clade 3C.2, which in the 2014-2015 NH influenza season exhibited considerable antigenic diversity such that it was assigned to a novel antigenic group (3C.2a).

Levels of intrahost viral variation vary between samples.

To characterize the intrahost variation within our influenza virus-infected hosts, we used next-generation sequence (NGS) data to identify minor variants (i.e., single nucleotide variants, or SNVs) at a frequency of ≥3% (Table 2). As defined, 66 SNVs were observed at frequencies ranging between 3% and 48.9%, with half at a frequency of >10%. Three minor variants were identified at frequencies above 40%: in the HA (48.9%), NA (46.9%), and PB2 (40.9%) genes of three separate samples. Of these, only one resulted in an amino acid change, V33I in the NA gene. Although SNVs were observed in all genes, 44% fell in those genes that encode the surface glycoproteins HA and neuraminidase (NA) (compared to the ∼24% expected by chance given their sequence length) and that experience the strongest immune selection pressure and evolve at the highest rates (23). Overall, 54% (37/68) of all the minor variants characterized encoded amino acid changes although none of these were identified in antigenically important regions or at positions known to confer resistance to antiviral drugs.

TABLE 2.

Minor variant frequencies present in coding sequences

| Virus subtype and sample | No. of minor variants at a frequency of ≥3% (no. present at a frequency of ≥1%) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB2 | PB1 | PA | HA | NP | NA | Ma | NSa | Total | |

| H1N1 | |||||||||

| SA/2/2013(H1) | 1 (7) | 1 (3) | 1 (4) | 6 (8) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 12 (28) |

| SA/3/2013(H1) | 0 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 5 (11) |

| AU/11/2015(H1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (2) | 3 (6) |

| AU/12/2015(H1) | 0 (0) | 0 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (5) |

| AU/13/2015(H1) | 0 (12) | 1 (11) | 1 (9) | 1 (9) | 0 (8) | 0 (10) | 0 (1) | 0 (1) | 3 (61) |

| SA/22/2015(H1) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (1) | 0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| SA/23/2015(H1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| H3N2 | |||||||||

| SA/1/2013(H3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| SA/4/2013(H3) | 0 (0) | 0 (1) | 0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (2) | 0 (4) |

| SA/5/2013(H3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (2) | 0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (1) | 1 (8) |

| AU/6/2014(H3) | 0 (1) | 0 (1) | 0 (1) | 0 (1) | 0 (1) | 0 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (2) | 0 (9) |

| AU/7/2014(H3) | 3 (5) | 2 (2) | 2 (7) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (1) | 11 (23) |

| SA/8/2014(H3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (1) |

| AU/15/2015(H3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| AU/16/2015(H3) | 0 (4) | 0 (8) | 1 (6) | 0 (2) | 0 (2) | 0 (3) | 0 (1) | 0 (9) | 1 (35) |

| AU/18/2015(H3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| AU/24/2015(H3) | 0 (8) | 3 (6) | 1 (4) | 0 (5) | 0 (5) | 0 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (2) | 4 (33) |

| SA/19/2015(H3) | 0 (1) | 0 (3) | 0 (1) | 1 (4) | 0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) |

| SA/20/2015(H3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (1) |

| SA/25/2015(H3) | 0 (0) | 0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (2) |

| SA/26/2015(H3) | 1 (8) | 0 (4) | 1 (4) | 1 (3) | 0 (3) | 9 (15) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12 (37) |

| SA/27/2015(H3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (1) | 1 (5) | 1 (9) |

| SA/28/2015(H3) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (1) | 2 (6) |

| SA/29/2015(H3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| SA/31/2015(H3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (1) | 1 (3) |

Coding sequence from the first start codon to the stop codon of the second coding gene.

The frequency of minor variants differed greatly between samples, ranging between 0 and 12 SNVs per sample, and none was present at sufficiently high levels to suggest coinfection using previously defined criteria (24). Twenty-two of the 25 samples contained five or fewer minor variants (with six samples containing no SNVs), with the three remaining samples, AU/7/2014(H3) (where AU is Australia), SA/2/2013(H1), and SA/26/2015(H3), containing 11, 12, and 12 SNVs, respectively. In samples SA/2/2013(H1) and SA/26/2015(H3), ≥50% of the minor variants were present in a single gene, in HA and NA, respectively, while the SNVs identified in AU/7/2014(H3) were spread equally throughout the genome. All nine minor variants observed in the NA gene of sample SA/26/2015(H3) were present at frequencies between 14.3% and 19.5%, suggesting that these variants maybe genetically linked such that a distinct NA haplotype was present (although such a pattern was not observed in any other genes, and we were unable to accurately reconstruct haplotypes). In contrast, the frequencies of the minor variants in the HA gene of sample SA/2/2013(H1) differed substantially, ranging from 3.3% to 48.9%, suggesting that these variants resulted from independent de novo mutations.

Genomic evidence for transmission clusters at the Hajj.

We next investigated potential transmission links between pilgrims by phylogenetic relatedness (Fig. 1), collection date (Table 1), the proximity of tent accommodation (Table 3), country of origin (Table 1), and the presence of shared minor variants (Fig. 5). Accordingly, samples were first grouped into potential transmission clusters based on their phylogenetic proximity, after which we determined the number of genome-level genetic differences between samples within each cluster. This resulted in the identification of eight potential transmission clusters (Table 3). To provide further evidence of direct transmission within these clusters, we explored sites of confirmed minor variants (Table 2) and determined whether the same SNVs were present in other samples within the same transmission group using a frequency cutoff of 1%.

TABLE 3.

Genetic similarity and accommodation tent information for the putative transmission clusters of influenza A viruses based on phylogenetic relatedness

| Group name | Group sample composition | Group genetic comparison |

Group accommodation |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence similarity (%) | No. of nucleotide differences | No. of amino acid differences | No. of shared minor variants | Tent no. | Maximum distance between tents | ||

| H1N1-2013 | SA/2/2013(H1) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 1 | SA11 | <50 m |

| SA/3/2013(H1) | SA8 | ||||||

| H1N1-2015a | AU/12/2015(H1) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | AU2 | 0 m |

| AU/13/2015(H1) | AU2 | ||||||

| H1N1-2015b | AU/11/2015(H1) | 99.95 | 7 | 1 | 1 | AU6 | >2 km |

| SA/22/2015(H1) | SA10 | ||||||

| SA/23/2015(H1) | SA10 | ||||||

| H3N2-2013 | SA/4/2013(H3) | 99.87 | 17 | 2 | 0 | SA31 | <100 m |

| SA/5/2013(H3) | SA16 | ||||||

| H3N2-2014 | AU/6/2014(H3) | 99.85 | 20 | 4 | 1 | AU12 | <100 m |

| AU/7/2014(H3) | AU13 | ||||||

| H3N2-2015a | SA/20/2015(H3) | 99.99 | 2 | 2 | 0 | SA38 | <100 m |

| SA/28/2015(H3) | SA35 | ||||||

| SA/29/2015(H3) | SA38 | ||||||

| H3N2-2015b | AU/16/2015(H3) | 99.95 | 7 | 2 | 0 | AU4 | >2 km |

| SA/25/2015(H3) | SA10 | ||||||

| H3N2-2015c | AU/15/2015(H3) | 99.99 | 2 | 2 | 0 | AU2 | 0 m |

| AU/24/2015(H3) | AU2 | ||||||

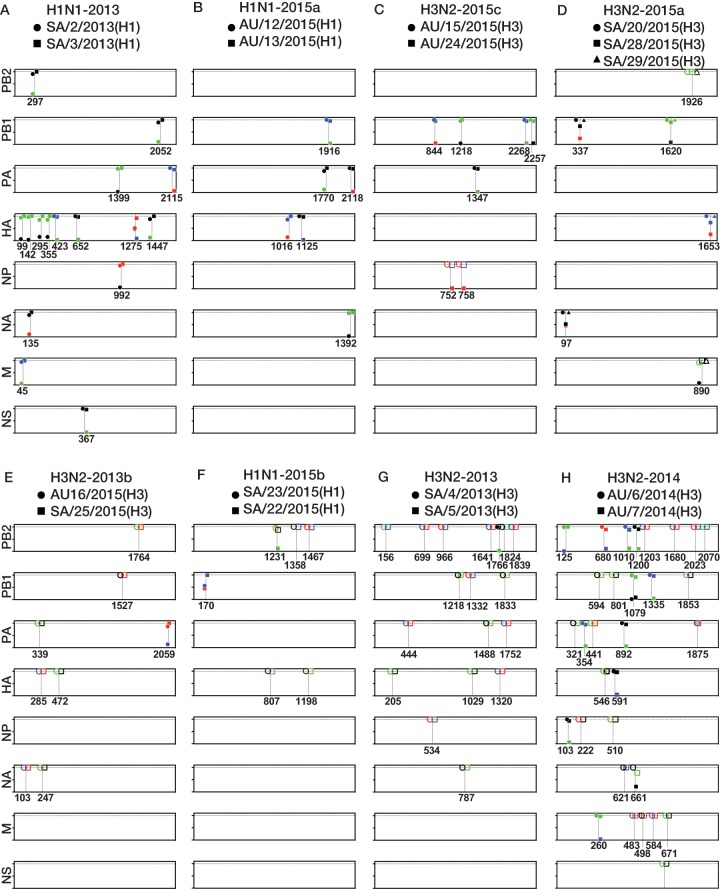

FIG 5.

Diagrammatic representation of the genetic differences between potential transmission groups and the distribution of minor variants. Each panel represents a potential transmission cluster. Boxes represent each of the coding genes, and the numbers below the boxes refer to the nucleotide positions in the coding genes. The y axis displays the nucleotide frequencies, with ticks corresponding to 0, 50, and 100% variant frequency. Nucleotides present are identified according to the following color scheme: green, A; red, U; blue, C; black, G. Open symbols indicate nucleotide fixation events between samples, and closed symbols represent positions of minor variants.

Intuitively, groups with similar consensus sequences are the most likely to represent a true transmission cluster. We therefore began with groups H1N1-2013 and H1N1-2015a that contained samples with identical genome sequences. Samples SA/2/2013(H1) and SA/3/2013(H1) from group H1N1-2013 were collected on the same day from Saudi pilgrims who stayed in separate yet closely positioned tents (i.e., within 50 m of each other). The samples had 12 and 5 SNVs, respectively, only 1 of which was shared between samples (Fig. 5A). Specifically, the minor variant at nucleotide 1275 in the HA gene was present at a frequency of 48.9% in sample SA/2/2013(H1) and at 8.5% in sample SA/3/2013(H1), with all additional variants present at lower frequencies. Together, the genetic data and the close proximity of the pilgrims' accommodations within the tent city strongly suggest that these samples are part of the same transmission cluster and may even constitute a donor/recipient pair. Group H1N1-2015a, containing samples AU/12/2015(H1) and AU/13/2015(H1), were similarly collected on the same day from Australian pilgrims who resided in the same tent. However, unlike the H1N1-2013 cluster described above, these samples harbored a lower number of minor variants (three each), none of which was shared between them (Fig. 5B). While the cohabitation of the pilgrims and the consensus sequence similarity suggest that these samples belong to the same transmission cluster, this cannot be confirmed with subconsensus genomic data.

Samples AU/15/2015(H3) and AU/24/2015(H3) comprised group H3N2-2015c and differed by two nucleotides in the NP gene, at positions 752 and 758, that resulted in A251V and I253T amino acid changes, respectively (Fig. 5C). At both positions a U nucleotide was fixed in sample AU/15/2015(H3), while in sample AU/24/2015(H3) a C nucleotide was dominant (at frequencies of 98.4% and 98.5%), with minor U variants present at frequencies of 1.6% at position 752 and 1.5% at nucleotide 758. Sample AU/15/2015(H3) was collected 3 days prior to collection of AU/24/2015(H3), and both samples were from Australian pilgrims residing in the same tent. This, together with the presence of the same nucleotides as the dominant or minor variant, makes transmission from AU/15/2015(H3) to AU/24/2015(H3) feasible. Indeed, these data are compatible with the idea that the de novo mutations at position 752 and 758 arose following viral transmission from AU/15/2015(H3) to AU/24/2015(H3) and were subsequently amplified throughout infection.

Group H3N2-2015a contained three samples from pilgrims of Saudi origin, SA/20/2015(H3), SA/28/2015(H3), and SA/29/2015(H3), the first of which was collected 3 days before the other two. Two nucleotide differences were identified between these samples (Fig. 5D). At nucleotide position 890 in the M gene, a G nucleotide was fixed in samples SA/28/2015(H3) and SA/29/2015(H3), while in SA/20/2015(H3), an A nucleotide was dominant (92%), with a minor G variant present at an 8% frequency. This nucleotide substitution encoded a V68I amino acid change in the M2 protein. This minor variant was not initially identified in our SNV calling due to primer strand biasing. However, due to this SNV's high frequency, position at the end of the gene, and presence at the site of nucleotide change, we assigned it as an SNV for this analysis. The samples SA/20/2015(H3) and SA/29/2015(H3) were from pilgrims who stayed in the same tent, while the pilgrim who was the source of SA/28/2015(H3) stayed in an adjacent tent. Hence, these data strongly suggest that these samples are part of a transmission cluster and that sample SA/20/2015(H3) was potentially a transmission donor to both SA/28/2015(H3) and SA/29/2015(H3) and that a mixed population at position 890 in the M gene was transmitted from SA/20/2015(H3) to SA/28/2015(H3) and SA/29/2015(H3). Following infection, the G nucleotide was then fixed by the time of sampling.

Transmission clusters are clearly harder to confirm in groups characterized by lower levels of sequence similarity. Two groups were identified that exhibited seven nucleotide differences. Samples AU/16/2015(H3) and SA/25/2015(H3), comprising group H3N2-2015b, were collected 3 days apart and were taken from Australian and Saudi pilgrims who resided in tents over 2 km apart. Only one minor variant was identified in the PA gene of sample AU/16/2015(H3) at a frequency of 13.6%, but it was not shared with sample SA/25/2015(H3) (Fig. 5E). No genetic or epidemiological evidence is therefore present to suggest that this pair constitutes a transmission group. Group H1N1-2015b contains three samples, AU/11/2015(H1), SA/22/2015(H1), and SA/23/2015(H1), the first of which was collected 3 days prior to the other two. While SA/22/2015(H1) and SA/23/2015(H1) were both collected from Saudi pilgrims staying in the same tent, AU/11/2015(H1) was collected from an Australian pilgrim whose tent was situated over 2 km away so that it is unlikely that AU/11/2015(H1) forms part of this transmission cluster. A total of five nucleotide differences were present between SA/23/2015(H1) and SA/22/2015(H1) alone (Fig. 5F), with an A nucleotide fixed at position 1231 in the PB2 gene of sample SA/23/2015(H1), and a G nucleotide dominant at 88%, with the minor variant A present at a 12% frequency in sample SA/22/2015(H1). Despite the higher numbers of nucleotide substitutions between the consensus sequences of these two samples, the presence of a minor variant at the site of a nucleotide change and the cohabitation of the pilgrims suggests that samples SA/22/2015(H1) and SA/23/2015(H1) could potentially represent a transmission cluster.

The final two groups, H3N2-2013 and H3N2-2014, consisted of samples that differed from each other at the genome level by 17 and 20 nucleotides, respectively. Samples SA/4/2013(H3) and SA/5/2013(H3), in group H3N2-2013, were collected on the same day from Saudi pilgrims staying in different tents and shared no minor variants, and thus they present little evidence for direct transmission, particularly given their high levels of sequence divergence (Fig. 5G). Samples AU/6/2014(H3) and AU/7/2014(H3), comprising group H3N2-2014, differed by 20 nucleotides and were collected 2 days apart from Australian pilgrims residing in different yet closely positioned tents. Interestingly, a minor G nucleotide variant at position 1079 in the PB1 gene was shared at frequencies of 1.4% and 8.5% in AU/6/2014(H3) and AU/7/2014(H3), respectively (Fig. 5H). Additionally, the fixed G nucleotide at position 661 in the NA gene of sample AU/6/2014(H3) was present in sample AU/7/2014(H3) at a 21.8% frequency with a dominant A nucleotide. While these data are compatible with these samples being part of a transmission cluster, the level of sequence divergence renders this unlikely. The shared minor variant is therefore more likely to have evolved convergently, to have been present as a minor variant that circulated at subconsensus levels in the Hajj population, or to have arisen simultaneously by chance.

DISCUSSION

To understand the drivers of influenza virus evolution within closed transmission environments like the Hajj it is important to characterize the genetic diversity and the biological mechanisms that contribute to that diversity. This information will not only add to our general understanding of influenza virus evolution at the scale of individual outbreaks but also aid public health planning and directed surveillance at MGs. Here, we used deep-sequence analysis of samples collected from Hajj pilgrims presenting with ILI over a 3-year period to characterize the interhost and intrahost genomic diversity of influenza viruses.

Laboratory confirmation of influenza in this study was generally low, at 4.7% of ILI cases, compared to the high rates (10% to 14%) in most other previous studies (16, 25–29). This may be in part because only pilgrims presenting with both fever and respiratory tract symptoms were sampled, necessarily excluding those with asymptomatic or mild infections. It has previously been demonstrated that 11.6% of asymptomatic Hajj pilgrims can have RT-PCR-confirmed influenza (29). Therefore, by limiting sampling to pilgrims with fever and respiratory tract symptoms, we may have missed a substantial proportion of infected individuals.

In all 3 years sampled, a higher proportion of influenza illness was due to A(H3N2) than A(H1N1) viruses, with 74% of overall influenza virus infections sampled here caused by A(H3N2) viruses. This mirrored all globally sampled and subtyped influenza A virus illnesses in the 4 weeks leading up to the 2013-2015 Hajj events, in which 65% in 2013, 86% in 2014, and 83% in 2015 were caused by A(H3N2) viruses (www.who.int/flunet). In contrast, lower levels of disease were caused by A(H3N2) in Saudi Arabia and surrounding countries: 51% in 2013, 57% in 2014, and 5% in 2015 (www.who.int/flunet). Previous work has also shown that a higher proportion of illness at the Hajj gatherings during this period was caused by A(H3N2) viruses than by A(H1N1) viruses. For example, in Egyptian pilgrims sampled at the 2012-2015 Hajj gatherings, A(H3N2) viruses were responsible for 62% of all influenza A viruses detected (29), and all influenza A viruses detected in Jordanian Hajj pilgrims in 2014 were subtyped as A(H3N2) (30).

The genetic diversity of influenza A viruses manifest at the interhost (epidemiological) level also mirrored the genetic diversity of viruses circulating globally. Phylogenetic analysis showed that this genetic diversity was due to the introduction of multiple viruses into the Hajj each year. While only low numbers of influenza virus infections were identified, of the three 2013 A(H3N2) viruses, examples from both antigenic groups circulating globally were isolated. In 2015, only one of the two dominant antigenic A(H3N2) groups that circulated globally in 2015 was observed at the Hajj (31). The various introductions appeared to originate from a diverse set of geographic locations, including West Africa, Southeast Asia, North and South America, Europe, and Australia. Indeed, circulation of influenza virus was confirmed among Hajj pilgrims from many of these regions (16, 28, 29, 32–34). However, it was difficult to determine the country or area of origin due to the lack of phylogenetic resolution, inadequate sampling, and the level of lineage mixing observed at the global level.

As noted above, our phylogenetic analysis indicates that much of the influenza A virus diversity in the Hajj pilgrimages resulted from multiple introductions. With up to 3 million pilgrims attending the Hajj annually, the introduction of such diversity is unsurprising, especially with foreign pilgrims making up two-thirds of the participants. Following the influenza outbreak at the 2008 World Youth Day in Sydney, a diversification of circulating viruses was observed throughout Australia (6). Similarly, we observed two genetically distinct groups of A(H1N1) viruses at the Hajj in 2015. Of particular note was that group iii clustered with viruses circulating in and around Saudi Arabia prior to the 2015 Hajj (Fig. 4A), suggesting an amplification of a preexisting community virus. The other group (group ii) was more closely related to the viruses circulating in Saudi Arabia and neighboring countries following the 2015 Hajj; we postulate that these viruses were introduced into Saudi Arabia and the surrounding areas around the time of the 2015 Hajj and subsequently became more regionally widespread. This highlights that while much diversity can be sourced from the home countries of foreign pilgrims, viruses endemic to the host community can also contribute significantly to viral diversity at MGs. Additionally, foreign variants introduced to the Hajj can subsequently increase the genetic diversity of viruses circulating locally.

Deep-sequencing analysis also allowed us to characterize the intrahost mutational spectrum of seasonal influenza viruses in pilgrims attending the Hajj. Clearly, minor variants can either be transmitted from one infected individual to another or can arise de novo although it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between these two routes. While the characterization of intrahost evolution was not possible due to a lack of longitudinal samples, which is necessarily difficult during acute infections, we observed relatively limited subconsensus diversity within individual hosts. In particular, the majority of SNVs appeared to have arisen from de novo mutations as they were not shared between samples; however, we could not confirm this due to the short duration of the study and the limited transmission chains observed. In addition, many of the minor variants observed were likely to represent transient deleterious mutations, which were either removed by purifying selection, thereby explaining their rapid turnover, or not transmitted in the population due to stringent bottlenecks (35). This view accords with studies undertaken in other naturally (and acutely) infected influenza populations (including in avian, equine, and canine hosts) that have revealed a rapid turnover of genetic diversity (36–38).

Some studies of seasonal human influenza virus have revealed relatively loose transmission bottlenecks such that multiple variants can pass between hosts (24). At face value this idea conflicts with this study of influenza virus evolution during the Hajj where only one likely event of minor variant transmission was identified. Most notably, a previous household transmission study identified a consistently higher number of minor variants within each sample, with variants of frequencies greater than 10% having more than a 60% chance of being transmitted [64% for A(H1N1) and 86% for A(H3N2) viruses] (24). In contrast, in our study while 50% of minor variants identified had frequencies of >10%, only one was shared between samples. However, it is important to note that, in contrast to the household transmission study, all transmission events in our study were inferred rather than known, and our sampling necessarily excluded asymptomatic infections.

Minor variants can circulate at the epidemiological level and hence contribute to virus genetic diversity (24). While such variants can be fixed, or more likely lost, following interhost transmission, it is also possible that minor variants will continue to circulate in a population at subconsensus levels. An example is provided by samples AU/6/2014(H3) and AU/7/2014(H3) (group H3N2-2014) collected from Australian pilgrims. Although these samples grouped together on the phylogenetic tree, they differed at 20 nucleotide sites such that direct transmission between them was unlikely. Despite this, these two samples shared a low-frequency minor variant in the PB1 gene, which encoded a conservative amino acid change, K360R. It is therefore possible that this PB1 variant evolved convergently in these two hosts or circulated at low levels in the wider Hajj population, likely surviving multiple transmission bottlenecks. Unfortunately, the only additional positive sample of influenza A virus collected in 2014 was collected from a Saudi pilgrim, and it was of a genetically divergent lineage so that the full extent of spread of the PB1 variant is uncertain.

In sum, we have been able to characterize the genetically diverse population of influenza viruses at the Hajj gatherings and have highlighted the complexities of cocirculating strains and their variable geographic origins. The mixing of endemic local lineages with those introduced into the Hajj gatherings by foreign pilgrims also increases the opportunity for novel influenza virus reassortants to emerge. Taken together, the yearly level of circulating viral diversity, evidence of global dissemination of novel pathogens following outbreaks at the Hajj (12, 14), and the recent characterization of multidrug-resistant bacteria (39) highlight the threat the Hajj and other MGs pose to global health. Similar in-depth studies are clearly needed to improve public health planning and to help promote novel ways for surveillance at MGs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection.

The study design and sample collection procedures have been described previously (40). Ethics approval was received from an Australian Human Research Ethics Committee (NSW HREC reference no. HREC/13/HNE/265), the Joint Institutional Review Board (J-IRB) of Hamad Medical Corporation-Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar (IRB no. 13-0039), and from King Abdullah Medical City, Saudi Arabia (KAMC IRB reference no. 15-205). Briefly, nasopharyngeal or throat swabs were collected during the 2013, 2014, and 2015 Hajj gatherings from any pilgrim who was registered with the study of Wang et al. (40) and who presented with an influenza-like illness (ILI), defined as a fever and at least one respiratory symptom (19). At the time of sample collection, the country of origin and accommodation tent location of each pilgrim were recorded. RNA was extracted from all samples and multiplex reverse transcriptase PCRs (RT-PCRs) were performed to test for influenza A and B viruses, rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza viruses 1 to 3, human coronaviruses (OC43, 229E, and NL63), human metapneumovirus, enterovirus, and adenoviruses.

Genome amplification and DNA library preparation.

For all influenza A virus (IAV)-positive samples, a multisegment RT-PCR was used to produce cDNA and amplify all influenza genome segments from total RNA (41). DNA libraries were produced using a NexteraXT DNA sample preparation kit (Illumina), and libraries were confirmed by quantitative PCR using a universal KAPA library quantification kit for Illumina platforms (Kapa Biosystems). Quality and fragment size were then estimated using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Equimolar amounts of each sample were pooled for 2- by 150-bp paired-end sequencing performed on an MiSeq platform using a 300-cycle reagent kit (version 2) at the Ramaciotti Centre for Genomics (University of New South Wales, Australia).

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) data processing and genome assembly.

Geneious, version 7.1.9 (Biomatters, Auckland, New Zealand) (42) was used to analyze and process sequencing reads. First, forward and reverse barcode reads were paired. Sequences were then trimmed to remove poor-quality data according to their quality scores using the modified Mott algorithm, with an error probability cutoff of 0.001, and at least 15 bp and 2 bp at the 5′ and 3′ ends were removed, respectively. Trimmed and filtered sequences of less than 100 bp were discarded. The remaining reads were then initially mapped to randomly selected seasonal isolates from the influenza A(H1N1) and A(H3N2) subtypes from the year of sample collection: A/India/Nag123467/2013 (H1N1), A/Niigata/13F270/2014 (H1N1), A/Michigan/45/2015 (H1N1), A/Thailand/SN11893/2013 (H3N2), A/Hokkaido/13H009/2014 (H3N2), or A/Montana/28/2015 (H3N2). Consensus sequences were extracted, and filtered reads were subsequently remapped to these consensus sequences.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Overall, 25 complete genomes (i.e., consensus sequences) of influenza A viruses were sequenced, covering the Hajj gatherings in years 2013 (n = 5), 2014 (n = 3), and 2015 (n = 17). This produced a data set comprising seven A(H1N1) and 18 A(H3N2) viruses. Whole concatenated genomes containing the coding sequences of 10 genes (PB2-PB1-PA-HA-NA-NP-NA-M1-M2-NS1-NS2; the M1/M2 and NS1/NS2 genes were represented by the sequence from the first ATG to the last stop codon for each segment) were analyzed with relevant seasonal isolates as background (see below). Phylogenetic analyses of each individual gene segment were also performed to determine whether any of these sequences had a history of reassortment.

Concatenated sequences were aligned using Mafft (version 7.271) (43) and inspected manually, producing A(H1N1) and A(H3N2) data sets of 13,133 bp each in length. Alignments of individual gene segments produced the following data sets for the both A(H1N1) and A(H3N2) viruses: PB2, 2,280 bp; PB1, 2,274 bp; PA, 2,151 bp; HA, 1,701 bp; NP, 1,497 bp; NA, 1,410 bp; M, 982 bp; NS, 838 bp. Phylogenetic trees of these data were estimated using the maximum likelihood (ML) procedure in the PhyML, version 3.0 (44), package, employing the general time-reversible (GTR) nucleotide substitution model and a discrete gamma distribution (GTR+G) with four rate categories (Γ4). A combination of subtree pruning and regrafting (SPR) and nearest-neighbor interchange (NNI) branch swapping was used to estimate the best tree, and bootstrap support values were generated using 1,000 replications.

Phylogenetic analysis using the full-length hemagglutinin (HA) gene was also undertaken to place the Hajj samples in the context of viruses circulating in Saudi Arabia and neighboring countries in 2012 to 2016. The countries neighboring Saudi Arabia were defined as Yemen, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Iran, Kuwait, Iraq, Jordan, Egypt, Sudan, and Eritrea. Background sequences were compiled from the GISAID (Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data [http://platform.gisaid.org/]) database with all duplicate sequences removed; this resulted in A(H1N1) (n = 320) and A(H3N2) (n = 149) data sets of 1,689 bp in length (see Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). Phylogenetic trees were estimated as above but with bootstrap support values generated using 100 replicates.

Finally, to place the Hajj sequences in the context of those sampled globally, we performed a phylogenetic analysis using an expansive data set of HA sequences from the A(H1N1) (n = 5,161) and A(H3N2) (n = 7,642) subtypes from 2013, 2014, and 2015, again with duplicate sequences removed (Tables S3 and S4). These sequences were compiled from both the GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank/) and the GISAID databases. Sequence alignments were performed as described above, again resulting in HA data sets of 1,698 bp in length. The very large size of these HA data sets meant that ML phylogenetic trees were necessarily estimated using the RAxML program, version 8.2.4 (45), employing the GTR+G nucleotide substitution model and 100 bootstrap replicates.

Single nucleotide variant (SNV) calling.

Minor (i.e., subconsensus) variants within each patient were identified using procedures available within Geneious, version 7.9.1 (42); these apply statistical tests to minimize false positives caused by sequence-specific errors occurring during Illumina sequencing (46). Specifically, minor variants were only accepted if they had a maximum variant P value of less than 10−6 and a minimum strand bias P value of 10−5 when the bias exceeded 65%. To be as conservative as possible, minor variants were called at a frequency of ≥3% (24) and with a minimum coverage of 200 for each nucleotide (Table 4). To investigate the presence of minor variants shared between individuals within potential transmission groups, we called minor variants with the same stringent criteria but using a more liberal frequency cutoff of ≥1%. Haplotype reconstruction was not undertaken due to its reported poor performance in phasing haplotypes using short reads, especially in sequence mixtures with only low variant levels like those found in viral populations (47).

TABLE 4.

Number of mapped reads and average coverage

| Influenza A virus name | Subtype | Sample name | Total no. of reads | No. of mapped reads | % mapped reads | Avg coverage per genea |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB2 | PB1 | PA | HA | NP | NA | M | NS | ||||||

| A/Saudi Arabia/01/2013 (H3N2) | A(H3N2) | SA/1/2013(H3) | 585,677 | 577,943 | 98.7 | 4,303 | 3,879.5 | 3,415.2 | 7,758 | 8,713.8 | 6,369.4 | 11,105.9 | 3,490.2 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/02/2013 (H1N1) | A(H1N1) | SA/2/2013(H1) | 446,172 | 108,973 | 24.4 | 753.4 | 286.6 | 332.8 | 1,092 | 1,676.2 | 743.4 | 2,207.4 | 2,289.4 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/03/2013 (H1N1) | A(H1N1) | SA/3/2013(H1)a | 360,263 | 352,171 | 97.8 | 2,562.8 | 1,492 | 2,173.5 | 3,320.6 | 4,080.8 | 3,685.3 | 7,465.5 | 8,964.3 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/04/2013 (H3N2) | A(H3N2) | SA/4/2013(H3) | 556,520 | 555,056 | 99.7 | 3,895.4 | 3,491.4 | 3,275.8 | 7,012.4 | 8,067.3 | 6,456.8 | 12,966.7 | 2,990.7 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/05/2013 (H3N2) | A(H3N2) | SA/5/2013(H3) | 513,418 | 491,330 | 95.7 | 3,033.2 | 2,240.1 | 2,674.4 | 5,865.3 | 7,427.4 | 5,305.6 | 15,092.2 | 3,432.9 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/06/2014 (H3N2) | A(H3N2) | AU/6/2014(H3) | 534,829 | 501,038 | 93.7 | 3,243.5 | 3,217.3 | 2,573.5 | 6,888.8 | 8,491.7 | 3,166.1 | 13,631.4 | 2,815 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/07/2014 (H3N2) | A(H3N2) | AU/7/2014(H3) | 608,425 | 552,302 | 90.8 | 4,814.5 | 3,372.2 | 4,534 | 9,018.6 | 5,878.9 | 2,995.7 | 11,389.8 | 4,708.2 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/08/2014 (H3N2) | A(H3N2) | SA/8/2014(H3) | 501,946 | 478,631 | 95.4 | 3,094.9 | 2,745.9 | 2,301.2 | 6,887.9 | 6,334.5 | 6,227.2 | 12,053.2 | 2,273.4 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/11/2015 (H1N1) | A(H1N1) | AU/11/2015(H1) | 563,132 | 538,469 | 95.6 | 3,083.6 | 1,582.4 | 3,153.7 | 4,783.3 | 6,283 | 6,100.4 | 13,959.6 | 14,258.8 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/12/2015 (H1N1) | A(H1N1) | AU/12/2015(H1) | 446,508 | 423,583 | 94.9 | 2,816.9 | 1,926.6 | 3,051.2 | 4,463.3 | 5,409.4 | 4,680.2 | 8,586.9 | 8,167.7 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/13/2015 (H1N1) | A(H1N1) | AU/13/2015(H1) | 665,432 | 166,718 | 25.1 | 796.9 | 911.9 | 687.7 | 2,313.8 | 1,800.2 | 1,514.9 | 3,972.5 | 4,283.3 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/15/2015 (H3N2) | A(H3N2) | AU/15/2015(H3) | 587,802 | 586,569 | 99.8 | 3,997.6 | 4,168.2 | 3,539.1 | 7,258.6 | 8,056.2 | 7,353.7 | 13,729.4 | 1,980.5 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/16/2015 (H3N2) | A(H3N2) | AU/16/2015(H3) | 569,629 | 387,758 | 68.1 | 2,067.8 | 2,004.4 | 2,171 | 4,796 | 5,869.3 | 3,896.1 | 3,941.3 | 2,342.3 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/18/2015 (H3N2) | A(H3N2) | AU/18/2015(H3) | 542,560 | 529,183 | 97.5 | 3,788.8 | 3,177.6 | 3,611.4 | 6,080.1 | 7,541.5 | 6,467.8 | 12,569.5 | 2,356 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/19/2015 (H3N2) | A(H3N2) | SA/19/2015(H3) | 275,979 | 254,627 | 92.3 | 1,862.4 | 1,833.8 | 1,884.7 | 2,729.4 | 3,970 | 2,762.3 | 4,958.7 | 863.6 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/20/2015 (H3N2) | A(H3N2) | SA/20/2015(H3) | 480,547 | 462,532 | 96.3 | 2,673.1 | 2,907.4 | 2,603.8 | 6,743.8 | 6,135.3 | 5,417.4 | 12,755.9 | 1,303.8 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/22/2015 (H1N1) | A(H1N1) | SA/22/2015(H1) | 578,828 | 564,324 | 97.5 | 3,842.8 | 2,024.4 | 3,891.9 | 5,499.2 | 6,754.6 | 6,132.4 | 12,329.1 | 13,329.7 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/23/2015 (H1N1) | A(H1N1) | SA/23/2015(H1) | 584,093 | 484,307 | 82.9 | 3,023.2 | 1,900.4 | 2,989.3 | 5,695.6 | 5,982.8 | 5,400.5 | 10,097.6 | 10,862.1 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/24/2015 (H3N2) | A(H3N2) | AU/24/2015(H3) | 361,703 | 89,999 | 24.9 | 698.5 | 605.8 | 672 | 1364.6 | 1242.4 | 964.2 | 1529.7 | 277.4 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/25/2015 (H3N2) | A(H3N2) | SA/25/2015(H3) | 512,023 | 508,588 | 99.3 | 4,053.7 | 3,627.6 | 3,964.6 | 5,822.5 | 7,096.4 | 4,695.9 | 11,797.4 | 1,688.2 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/26/2015 (H3N2) | A(H3N2) | SA/26/2015(H3) | 760,636 | 56,018 | 7.4 | 335.2 | 341.1 | 512.8 | 899.3 | 661.9 | 595.6 | 1,241.4 | <200 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/27/2015 (H3N2) | A(H3N2) | SA/27/2015(H3) | 577,874 | 184,154 | 31.9 | 1,286.8 | 1,348.6 | 1,192.7 | 2,864.3 | 1,680.3 | 2,055.4 | 3,497 | 365.8 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/28/2015 (H3N2) | A(H3N2) | SA/28/2015(H3) | 569,664 | 569,100 | 99.9 | 4,392.9 | 3,582.5 | 4,047 | 7,001.4 | 7,527.2 | 6,702.9 | 12,772.5 | 1,905.8 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/29/2015 (H3N2) | A(H3N2) | SA/29/2015(H3) | 835,673 | 829,387 | 99.2 | 6,381.6 | 4,895.2 | 5,691.2 | 10,330.7 | 12,065.7 | 8,094.6 | 21,194.4 | 2,376.8 |

| A/Saudi Arabia/31/2015 (H3N2) | A(H3N2) | SA/31/2015(H3) | 579,952 | 579,256 | 99.9 | 3,857.3 | 3,029.5 | 4,436.4 | 7,487.8 | 7,263.8 | 5,713.8 | 12,427.8 | 1,389.8 |

Average number of times each nucleotide in the gene is sequenced.

Accession number(s).

All consensus sequences generated here have been submitted to GenBank and assigned accession numbers KY681478 to KY681677 while all intrahost sequence data have been submitted to the Sequence Read Archive under BioProject accession number PRJNA377792.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the Qatar National Research Fund (grant reference NPRP 6-1505-3-358) and by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre of Research Excellence in Population Health Research entitled “Immunization in Understudied and Special Risk Populations: Closing the Gap in Knowledge through a Multidisciplinary Approach.” E.C.H. is funded by an NHMRC Australia Fellowship (GNT1037231).

Members of the Hajj Research Team are Mohamed Tashani, Mohammad Irfan Azeem, Hamid Bokhary, Almamoon Badahdah, Haitham El Bashir, and Godwin Wilson.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00096-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. 2012. The Hajj: updated health hazards and current recommendations for 2012. Euro Surveill 17(41):pii=20295 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. 2012. Mass gatherings and infectious diseases: prevention, detection, and control. Infect Dis Clin North Am 26:725–737. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. 2014. Mass gathering medicine: 2014 Hajj and Umra preparation as a leading example. Int J Infect Dis 27:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alqahtani AS, Alfelali M, Arbon P, Booy R, Rashid H. 2015. Burden of vaccine preventable diseases at large events. Vaccine 33:6552–6563. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.09.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gautret P, Steffen R. 2016. Communicable diseases as health risks at mass gatherings other than Hajj: what is the evidence? Int J Infect Dis 47:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blyth CC, Foo H, van Hal SJ, Hurt AC, Barr IG, McPhie K, Armstrong PK, Rawlinson WD, Sheppeard V, Conaty S, Staff M, Dwyer DE, World Youth Day Influenza Study Group. 2010. Influenza outbreaks during World Youth Day 2008 mass gathering. Emerg Infect Dis 16:809–815. doi: 10.3201/eid1605.091136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zepeda-Lopez HM, Perea-Araujo L, Miliar-Garcia A, Dominguez-Lopez A, Xoconostle-Cazarez B, Lara-Padilla E, Ramirez Hernandez JA, Sevilla-Reyes E, Orozco ME, Ahued-Ortega A, Villasenor-Ruiz I, Garcia-Cavazos RJ, Teran LM. 2010. Inside the outbreak of the 2009 influenza A (H1N1)v virus in Mexico. PLoS One 5:e13256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wharton M, Spiegel RA, Horan JM, Tauxe RV, Wells JG, Barg N, Herndon J, Meriwether RA, MacCormack JN, Levine RH. 1990. A large outbreak of antibiotic-resistant shigellosis at a mass gathering. J Infect Dis 162:1324–1328. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.6.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Memish ZA, Stephens GM, Steffen R, Ahmed QA. 2012. Emergence of medicine for mass gatherings: lessons from the Hajj. Lancet Infect Dis 12:56–65. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70337-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed QA, Memish ZA. 2016. Hajj 2016: required vaccinations, crowd control, novel wearable tech and the Zika threat. Travel Med Infect Dis 14:429–432. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balaban V, Stauffer WM, Hammad A, Afgarshe M, Abd-Alla M, Ahmed Q, Memish ZA, Saba J, Harton E, Palumbo G, Marano N. 2012. Protective practices and respiratory illness among US travelers to the 2009 Hajj. J Travel Med 19:163–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2012.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aguilera JF, Perrocheau A, Meffre C, Hahne S, W135 Working Group. 2002. Outbreak of serogroup W135 meningococcal disease after the Hajj pilgrimage, Europe, 2000. Emerg Infect Dis 8:761–767. doi: 10.3201/eid0808.010422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taha MK, Achtman M, Alonso JM, Greenwood B, Ramsay M, Fox A, Gray S, Kaczmarski E. 2000. Serogroup W135 meningococcal disease in Hajj pilgrims. Lancet 356:2159. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayer LW, Reeves MW, Al-Hamdan N, Sacchi CT, Taha MK, Ajello GW, Schmink SE, Noble CA, Tondella ML, Whitney AM, Al-Mazrou Y, Al-Jefri M, Mishkhis A, Sabban S, Caugant DA, Lingappa J, Rosenstein NE, Popovic T. 2002. Outbreak of W135 meningococcal disease in 2000: not emergence of a new W135 strain but clonal expansion within the electrophoretic type-37 complex. J Infect Dis 185:1596–1605. doi: 10.1086/340414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Memish ZA, Assiri A, Turkestani A, Yezli S, Al Masri M, Charrel R, Drali T, Gaudart J, Edouard S, Parola P, Gautret P. 2015. Mass gathering and globalization of respiratory pathogens during the 2013 Hajj. Clin Microbiol Infect 21:571.e1–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benkouiten S, Charrel R, Belhouchat K, Drali T, Nougairede A, Salez N, Memish ZA, Al Masri M, Fournier PE, Raoult D, Brouqui P, Parola P, Gautret P. 2014. Respiratory viruses and bacteria among pilgrims during the 2013 Hajj. Emerg Infect Dis 20:1821–1827. doi: 10.3201/eid2011.140600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salmon-Rousseau A, Piednoir E, Cattoir V, de La Blanchardiere A. 2016. Hajj-associated infections. Med Mal Infect 46:346–354. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balkhy HH, Memish ZA, Bafaqeer S, Almuneef MA. 2004. Influenza a common viral infection among Hajj pilgrims: time for routine surveillance and vaccination. J Travel Med 11:82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barasheed O, Rashid H, Alfelali M, Tashani M, Azeem M, Bokhary H, Kalantan N, Samkari J, Heron L, Kok J, Taylor J, El Bashir H, Memish ZA, Haworth E, Holmes EC, Dwyer DE, Asghar A, Booy R, Hajj Research T. 2014. Viral respiratory infections among Hajj pilgrims in 2013. Virol Sin 29:364–371. doi: 10.1007/s12250-014-3507-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Memish ZA, Assiri A, Almasri M, Alhakeem RF, Turkestani A, Al Rabeeah AA, Akkad N, Yezli S, Klugman KP, O'Brien KL, van der Linden M, Gessner BD. 2015. Impact of the Hajj on pneumococcal transmission. Clin Microbiol Infect 21:77.e11–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Memish ZA, Zumla A, Alhakeem RF, Assiri A, Turkestani A, Al Harby KD, Alyemni M, Dhafar K, Gautret P, Barbeschi M, McCloskey B, Heymann D, Al Rabeeah AA, Al-Tawfiq JA. 2014. Hajj: infectious disease surveillance and control. Lancet 383:2073–2082. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60381-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yezli S, Assiri AM, Alhakeem RF, Turkistani AM, Alotaibi B. 2016. Meningococcal disease during the Hajj and Umrah mass gatherings. Int J Infect Dis 47:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fitch WM, Leiter JM, Li XQ, Palese P. 1991. Positive Darwinian evolution in human influenza A viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88:4270–4274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poon LL, Song T, Rosenfeld R, Lin X, Rogers MB, Zhou B, Sebra R, Halpin RA, Guan Y, Twaddle A, DePasse JV, Stockwell TB, Wentworth DE, Holmes EC, Greenbaum B, Peiris JS, Cowling BJ, Ghedin E. 2016. Quantifying influenza virus diversity and transmission in humans. Nat Genet 48:195–200. doi: 10.1038/ng.3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rashid H, Shafi S, Booy R, El Bashir H, Ali K, Zambon M, Memish Z, Ellis J, Coen P, Haworth E. 2008. Influenza and respiratory syncytial virus infections in British Hajj pilgrims. Emerg Health Threats J 1:e2. doi: 10.3134/ehtj.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rashid H, Shafi S, Haworth E, El Bashir H, Memish ZA, Sudhanva M, Smith M, Auburn H, Booy R. 2008. Viral respiratory infections at the Hajj: comparison between UK and Saudi pilgrims. Clin Microbiol Infect 14:569–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.01987.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moattari A, Emami A, Moghadami M, Honarvar B. 2012. Influenza viral infections among the Iranian Hajj pilgrims returning to Shiraz, Fars province, Iran. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 6:e77–e79. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2012.00380.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Annan A, Owusu M, Marfo KS, Larbi R, Sarpong FN, Adu-Sarkodie Y, Amankwa J, Fiafemetsi S, Drosten C, Owusu-Dabo E, Eckerle I. 2015. High prevalence of common respiratory viruses and no evidence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Hajj pilgrims returning to Ghana, 2013. Trop Med Int Health 20:807–812. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Refaey S, Amin MM, Roguski K, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Uyeki TM, Labib M, Kandeel A. 2017. Cross-sectional survey and surveillance for influenza viruses and MERS-CoV among Egyptian pilgrims returning from Hajj during 2012-2015. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 11:57–60. doi: 10.1111/irv.12429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Abdallat MM, Rha B, Alqasrawi S, Payne DC, Iblan I, Binder AM, Haddadin A, Nsour MA, Alsanouri T, Mofleh J, Whitaker B, Lindstrom SL, Tong S, Ali SS, Dahl RM, Berman L, Zhang J, Erdman DD, Gerber SI. 2017. Acute respiratory infections among returning Hajj pilgrims-Jordan, 2014. J Clin Virol 89:34–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J, Zhou YY, Kou Y, Yu XF, Zheng ZB, Yang XH, Wang HQ. 2015. Interim estimates of divergence date and vaccine strain match of human influenza A(H3N2) virus from systematic influenza surveillance (2010–2015) in Hangzhou, southeast of China. Int J Infect Dis 40:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aberle JH, Popow-Kraupp T, Kreidl P, Laferl H, Heinz FX, Aberle SW. 2015. Influenza A and B Viruses but not MERS-CoV in Hajj pilgrims, Austria, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis 21:726–727. doi: 10.3201/eid2104.141745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Memish ZA, Almasri M, Turkestani A, Al-Shangiti AM, Yezli S. 2014. Etiology of severe community-acquired pneumonia during the 2013 Hajj-part of the MERS-CoV surveillance program. Int J Infect Dis 25:186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koul PA, Mir H, Saha S, Chadha MS, Potdar V, Widdowson MA, Lal RB, Krishnan A. 2016. Influenza not MERS CoV among returning Hajj and Umrah pilgrims with respiratory illness, Kashmir, north India, 2014–15. Travel Med Infect Dis 15:45–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Varble A, Albrecht RA, Backes S, Crumiller M, Bouvier NM, Sachs D, Garcia-Sastre A, ten Oever BR. 2014. Influenza A virus transmission bottlenecks are defined by infection route and recipient host. Cell Host Microbe 16:691–700. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoelzer K, Murcia PR, Baillie GJ, Wood JL, Metzger SM, Osterrieder N, Dubovi EJ, Holmes EC, Parrish CR. 2010. Intrahost evolutionary dynamics of canine influenza virus in naive and partially immune dogs. J Virol 84:5329–5335. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02469-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murcia PR, Baillie GJ, Daly J, Elton D, Jervis C, Mumford JA, Newton R, Parrish CR, Hoelzer K, Dougan G, Parkhill J, Lennard N, Ormond D, Moule S, Whitwham A, McCauley JW, McKinley TJ, Holmes EC, Grenfell BT, Wood JL. 2010. Intra- and interhost evolutionary dynamics of equine influenza virus. J Virol 84:6943–6954. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00112-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murcia PR, Hughes J, Battista P, Lloyd L, Baillie GJ, Ramirez-Gonzalez RH, Ormond D, Oliver K, Elton D, Mumford JA, Caccamo M, Kellam P, Grenfell BT, Holmes EC, Wood JL. 2012. Evolution of an Eurasian avian-like influenza virus in naive and vaccinated pigs. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002730. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leangapichart T, Gautret P, Griffiths K, Belhouchat K, Memish Z, Raoult D, Rolain J-M. 2016. Acquisition of a high diversity of bacteria during the Hajj pilgrimage, including Acinetobacter baumannii with blaOXA-72 and Escherichia coli with blaNDM-5 carbapenemase genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:5942–5948. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00669-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang M, Barasheed O, Rashid H, Booy R, El Bashir H, Haworth E, Ridda I, Holmes EC, Dwyer DE, Nguyen-Van-Tam J, Memish ZA, Heron L. 2015. A cluster-randomised controlled trial to test the efficacy of facemasks in preventing respiratory viral infection among Hajj pilgrims. J Epidemiol Glob Health 5:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou B, Wentworth DE. 2012. Influenza A virus molecular virology techniques. Methods Mol Biol 865:175–192. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-621-0_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Meintjes P, Drummond A. 2012. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuraku S, Zmasek CM, Nishimura O, Katoh K. 2013. aLeaves facilitates on-demand exploration of metazoan gene family trees on MAFFT sequence alignment server with enhanced interactivity. Nucleic Acids Res 41:W22–W28. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guindon S, Gascuel O. 2003. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol 52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stamatakis A. 2006. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakamura K, Oshima T, Morimoto T, Ikeda S, Yoshikawa H, Shiwa Y, Ishikawa S, Linak MC, Hirai A, Takahashi H, Altaf-Ul-Amin M, Ogasawara N, Kanaya S. 2011. Sequence-specific error profile of Illumina sequencers. Nucleic Acids Res 39:e90. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schirmer M, Sloan WT, Quince C. 2014. Benchmarking of viral haplotype reconstruction programmes: an overview of the capacities and limitations of currently available programmes. Brief Bioinform 15:431–442. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.