Abstract

Background

Research on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following natural and human-made disasters has been undertaken for more than three decades. Although PTSD prevalence estimates vary widely, most are in the 20–40% range in disaster-focused studies but considerably lower (3–5%) in the few general population epidemiological surveys that evaluated disaster-related PTSD as part of a broader clinical assessment. The World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys provide an opportunity to examine disaster-related PTSD in representative general population surveys across a much wider range of sites than in previous studies.

Method

Although disaster-related PTSD was evaluated in 18 WMH surveys, only six in high-income countries had enough respondents for a risk factor analysis. Predictors considered were socio-demographics, disaster characteristics, and pre-disaster vulnerability factors (childhood family adversities, prior traumatic experiences, and prior mental disorders).

Results

Disaster-related PTSD prevalence was 0.0–3.8% among adult (ages 18+) WMH respondents and was significantly related to high education, serious injury or death of someone close, forced displacement from home, and pre-existing vulnerabilities (prior childhood family adversities, other traumas, and mental disorders). Of PTSD cases 44.5% were among the 5% of respondents classified by the model as having highest PTSD risk.

Conclusion

Disaster-related PTSD is uncommon in high-income WMH countries. Risk factors are consistent with prior research: severity of exposure, history of prior stress exposure, and pre-existing mental disorders. The high concentration of PTSD among respondents with high predicted risk in our model supports the focus of screening assessments that identify disaster survivors most in need of preventive interventions.

Keywords: Disaster, post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD

Introduction

Natural and human-made disasters are increasingly common occurrences around the globe (Lopes et al. 2014; Warsini et al. 2014). Systematic research on development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following disasters has been undertaken for more than three decades, with most studies reporting only short-term consequences. Recent reviews suggest that between 20% (North, 2014) and 40% (Neria et al. 2008) of survivors develop PTSD, but the range across studies is extremely broad (5–60% following natural disasters; 25–75% following human-made disasters) (Galea et al. 2005) due to differences in the characteristics/locations of disasters and methodological differences in studies (Norris et al. 2006; Goldmann & Galea, 2014).

A handful of general population epidemiological surveys retrospectively assessed lifetime exposure to disasters and prevalence of post-disaster PTSD. The first such study, the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS; Kessler et al. 1995), found that much lower proportions of disaster survivors developed post-disaster PTSD (3.7% of men, 5.4% of women) than in disaster-focused studies. More recent community epidemiological surveys in Europe (Ferry et al. 2014; Olaya et al. 2015) and the United States (Breslau et al. 1998, 2013) found similar results. Importantly, PTSD prevalence estimates in these surveys were considerably higher for some other lifetime traumatic experiences (Molnar et al. 2001; Darves-Bornoz et al. 2008; Olaya et al. 2015), suggesting that the low post-disaster PTSD prevalence estimates were not due to recall bias. The discrepancy between these low prevalence estimates in representative community samples and much higher estimates in post-disaster surveys raises the question whether demand characteristics and unrepresentative samples led to upwardly biased estimates in post-disaster surveys (Bonanno et al. 2010).

We attempt to shed light on this question by presenting data on prevalence-correlates of disaster-related PTSD in the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys. Measures of severity of exposure to disaster-related stressors are among the strongest risk factors for PTSD in post-disaster surveys (Fergusson et al. 2014; Goldmann & Galea, 2014; Bromet et al. 2016). Other key risk factors include pre-disaster psychopathology, female gender, younger age at the time of the disaster, and early childhood adversity (Sayed et al. 2015). We use information about these potential predictors to examine PTSD prevalence and correlates among respondents in a series of WMH surveys who reported lifetime exposure to disasters.

Method and materials

Samples

Data come from the 18 WMH surveys that used an expanded assessment of PTSD (described below) to examine PTSD associated with randomly selected traumatic experiences (Table 1). These surveys included 10 in countries classified by The World Bank (2012) as high-income countries [national surveys in Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Northern Ireland, Spain, United States, along with regional surveys in Japan (a number of metropolitan areas) and Spain (Murcia)] and eight in countries classified as low-/middle-income countries (national surveys in Lebanon, Peru, Romania, South Africa, and Ukraine along with surveys of all non-rural areas in Colombia and Mexico and a separate regional survey in Medellin, Colombia). Each survey was based on a probability sample of household residents in the target population using a multi-stage clustered area probability design. Response rates had weighted averages of 84.7% in low-/lower-middle-income countries, 79.8% in upper-middle-income countries, 63.5% in high-income countries, and 70.3% overall. Four surveys had response rates below the minimally acceptable level of 60% (45.9% in France, 50.6% in Belgium, 55.1% in Japan, 56.4% in The Netherlands). A detailed description of sampling procedures is presented elsewhere (Heeringa et al. 2008).

Table 1.

World Mental Health (WMH) sample characteristics by World Bank income categoriesa

| Surveyb | Sample characteristicsc | Field dates | Age range | Sample size

|

Response rated | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part I | Part II | ||||||

| I. Low- and lower-middle-income countries | |||||||

| Colombia | NSMH | All urban areas of the country (~73% of the total national population) | 2003 | 18–65 | 4426 | 2381 | 87.7 |

| Peru | EMSMP | Nationally representative | 2004–2005 | 18–65 | 3930 | 1801 | 90.2 |

| Ukraine | CMDPSD | Nationally representative | 2002 | 18–91 | 4725 | 1720 | 78.3 |

| Total | 13 081 | 5902 | 84.7 | ||||

| II. Upper-middle-income countries | |||||||

| Colombia – Medelline | MMHHS | Medellin metropolitan area | 2011–2012 | 19–65 | 3261 | 1673 | 97.2 |

| Lebanon | LEBANON | Nationally representative | 2002–2003 | 18–94 | 2857 | 1031 | 70.0 |

| Mexico | M-NCS | All urban areas of the country (~75% of the total national population) | 2001–2002 | 18–65 | 5782 | 2362 | 76.6 |

| Romania | RMHS | Nationally representative | 2005–2006 | 18–96 | 2357 | 2357 | 70.9 |

| South Africaf | SASH | Nationally representative | 2003–2004 | 18–92 | 4315 | 4315 | 87.1 |

| Total | 18 572 | 11 738 | 79.8 | ||||

| III. High-income countries | |||||||

| Belgium | ESEMeD | Nationally representative, sample selected from a national register of Belgium residents | 2001–2002 | 18–95 | 2419 | 1043 | 50.6 |

| France | ESEMeD | Nationally representative, sample selected from a national list of households with listed telephone numbers | 2001–2002 | 18–97 | 2894 | 1436 | 45.9 |

| Germany | ESEMeD | Nationally representative | 2002–2003 | 19–95 | 3555 | 1323 | 57.8 |

| Italy | ESEMeD | Nationally representative, sample selected from municipality resident registries | 2001–2002 | 18–100 | 4712 | 1779 | 71.3 |

| Japan | WMHJ 2002–2006 | Eleven metropolitan areas | 2002–2006 | 20–98 | 4129 | 1682 | 55.1 |

| Netherlands | ESEMeD | Nationally representative, sample selected from municipal postal registries | 2002–2003 | 18–95 | 2372 | 1094 | 56.4 |

| N. Ireland | NISHS | Nationally representative | 2004–2007 | 18–97 | 4340 | 1986 | 68.4 |

| Spain | ESEMeD | Nationally representative | 2001–2002 | 18–98 | 5473 | 2121 | 78.6 |

| Spain – Murcia | PEGASUS-Murcia | Murcia region | 2010–2012 | 18–96 | 2621 | 1459 | 67.4 |

| United States | NCS-R | Nationally representative | 2002–2003 | 18–99 | 9282 | 5692 | 70.9 |

| Total | 41 797 | 19 615 | 63.5 | ||||

| IV. Total | 73 450 | 37 255 | 70.3 | ||||

The World Bank (2012) data. Accessed 12 May 2012 at: http://data.worldbank.org/country. Some of the WMH countries have moved into new income categories since the surveys were conducted. The income groupings above reflect the status of each country at the time of data collection. The current income category of each country is available at the preceding URL.

NSMH (The Colombian National Study of Mental Health); EMSMP (La Encuesta Mundial de Salud Mental en el Peru); CMDPSD (Comorbid Mental Disorders during Periods of Social Disruption); MMHHS (Medellín Mental Health Household Study); LEBANON (Lebanese Evaluation of the Burden of Ailments and Needs of the Nation); M-NCS (The Mexico National Comorbidity Survey); RMHS (Romania Mental Health Survey); SASH (South Africa Health Survey); ESEMeD (The European Study Of The Epidemiology Of Mental Disorders); WMHJ 2002–2006 (World Mental Health Japan Survey); NISHS (Northern Ireland Study of Health and Stress); PEGASUS-Murcia (Psychiatric Enquiry to General Population in Southeast Spain-Murcia); NCS-R (The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication)

Most WMH surveys are based on stratified multistage clustered area probability household samples in which samples of areas equivalent to counties or municipalities in the United States were selected in the first stage followed by one or more subsequent stages of geographic sampling (e.g. towns within counties, blocks within towns, households within blocks) to arrive at a sample of households, in each of which a listing of household members was created and one or two people were selected from this listing to be interviewed. No substitution was allowed when the originally sampled household resident could not be interviewed. These household samples were selected from Census area data in all countries other than France (where telephone directories were used to select households) and The Netherlands (where postal registries were used to select households). Several WMH surveys (Belgium, Germany, Italy) used municipal resident registries to select respondents without listing households. The Japanese sample is the only totally unclustered sample, with households randomly selected in each of the 11 metropolitan areas and one random respondent selected in each sample household. Thirteen of the 18 surveys are based on nationally representative household samples

The response rate is calculated as the ratio of the number of households in which an interview was completed to the number of households originally sampled, excluding from the denominator households known not to be eligible either because of being vacant at the time of initial contact or because the residents were unable to speak the designated languages of the survey. The weighted average response rate is 70.3%.

Colombia moved from the ‘lower and lower-middle-income’ to the ‘upper-middle-income’ category between 2003 (when the Colombian National Study of Mental Health was conducted) and 2010 (when the Medellin Mental Health Household Study was conducted), hence Colombia’s appearance in both income categories. For more information, please see Table note a.

For the purposes of cross-national comparisons we limit the sample to those aged 18+.

Field procedures

Interviews were administered face-to-face in respondents’ homes after obtaining informed consent using procedures approved by local Institutional Review Boards. The interview schedule was developed in English and translated into other languages using a standardized WHO translation, back-translation, and harmonization protocol (Harkness et al. 2008). Bilingual supervisors were trained and supervised by the WMH Data Collection Coordination Centre to guarantee cross-national consistency in field procedures (Harkness et al. 2008).

Interviews were conducted in two parts. Part I was administered to all respondents and assessed core DSM-IV mental disorders (n = 73 450 respondents across all surveys). Part II assessed additional disorders and correlates. Questions about traumatic experiences and PTSD were included in Part II, which was administered to 100% of respondents who met lifetime criteria for any Part I disorder and a probability subsample of other Part I respondents (n = 37 255). Part II respondents were weighted to adjust for differential probabilities of selection, selection into Part II, and deviations between the sample and population demographic-geographic distributions. More details about WMH weighting are presented elsewhere (Heeringa et al. 2008).

Measures

Exposure to traumatic experiences

Part II respondents were asked about lifetime exposure to each of 27 different types of traumatic experiences (TEs) in addition to two open-ended questions about exposure to ‘any other’ TE and to a ‘private’ TE the respondent did not want to name. Respondents were presented with a TE list and asked to report lifetime exposure to each type. Positive responses were followed by probes to assess the number of lifetime exposures and age at first exposure to each type. Missing values were rare because the surveys were interviewer-administered, but were coded conservatively as indicating that the TE did not occur. A total of n = 14 127 respondents reported lifetime exposure to at least one TE. Exploratory factor analysis found six broad correlated groups of TEs: four of exposure to organized violence (e.g. civilian in a war zone, relief worker in a war zone, refugee); five related to participation in organized violence (e.g. combat experience, saw atrocities); three of exposure to interpersonal violence (witnessed violence at home as a child, beaten by a caregiver as a child, beaten by someone else other than a romantic partner); seven related to sexual violence (e.g. raped, sexually assaulted, beaten by a romantic partner); six of accidents/injuries (e.g. natural disaster, toxic chemical exposure, motor vehicle accident); and a final three not strongly correlated with other TEs (mugged or threatened with a weapon, exposure to a human-made disaster other than toxic chemical exposure, unexpected death of someone close) (Benjet et al. 2016).

Randomly selected traumatic experiences

One lifetime occurrence of one reported TE type was selected randomly for each respondent for more detailed assessment. Once this occurrence was selected, a short set of TE-specific questions was asked about characteristics of the randomly selected TE. PTSD in the wake of that occurrence was then assessed. The TE question about natural disasters was ‘Were you ever involved in a major natural disaster, like a devastating flood, hurricane, or earthquake?’ The comparable question for human-made disasters was ‘Were you ever in a man-made disaster, like a fire started by a cigarette, or a bomb explosion?’ When either of these was the randomly selected TE, four additional TE-specific questions were asked: whether the respondent was seriously injured in the disaster; whether the respondent was displaced (i.e. forced to leave their home) by the disaster; whether anyone close to the respondent was seriously injured or died in the disaster; and whether the respondent witnessed anyone die during the disaster.

Post-disaster PTSD assessment

PTSD in the wake of the randomly selected TE was assessed with the PTSD section of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; Kessler & Ustun, 2004), a fully structured interview administered by trained lay interviewers. DSM-IV criteria were used. Criterion A1 (exposure to an experience involving threatened death or serious injury) was assumed to exist by virtue of endorsing the TE question. Criterion A2 (intense, fear, helplessness, or horror) was not required, but Criteria B (persistent re-experiencing), C (avoidance-numbing), D (increased arousal), E (minimum duration of more than 1 month), and E (clinically significant distress or impairment) were all required. As detailed elsewhere (Haro et al. 2006), blinded clinical reappraisal interviews with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) conducted in four WMH countries found CIDI-SCID concordance for DSM-IV PTSD to be moderate (Landis & Koch, 1977) (AUC = 0.69). Sensitivity and specificity were 0.38 and 0.99, respectively, resulting in a positive likelihood ratio (LR+) of 42.0, which is well above the threshold of 10 typically used to consider screening scale diagnoses definitive (Gardner & Altman, 2000). Consistent with the high LR+, the proportion of CIDI cases confirmed by the SCID was 86.1%. This means the vast majority of CIDI/DSM-IV PTSD cases would independently be confirmed by a blinded trained clinician. Missing symptom reports, which were rare, were coded conservatively as the symptoms being absent.

Other mental disorders

The CIDI was also used to assess 14 prior (to the respondent’s age of exposure to the randomly selected TE) lifetime DSM-IV mental disorders, including two mood disorders [major depressive disorder/dysthymic disorder and broadly defined bipolar disorder (BPD; including BP-I, BP-II, and subthreshold BPD defined using criteria described elsewhere [Kessler et al. 2006])], six anxiety disorders [panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, specific phobia, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, prior (to the randomly selected TE) PTSD, and separation anxiety disorder], four disruptive behaviour disorders (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional-defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and intermittent explosive disorder), and two substance disorders (alcohol abuse with or without dependence, drug abuse with or without dependence). Age-of-onset (AOO) of each disorder was assessed using special probing techniques shown experimentally to improve recall accuracy (Knauper et al. 1999) allowing us to determine, using retrospective AOO reports, whether each respondent had a history of each disorder prior to occurrence of the randomly selected TE. DSM-IV organic exclusion rules and diagnostic hierarchy rules were used (other than ODD, which was defined with or without CD, and substance abuse, which was defined with or without dependence). As detailed elsewhere (Haro et al. 2006), generally good concordance was found between these CIDI diagnoses and blinded clinical diagnoses based on SCID clinical reappraisal interviews (First et al. 1994). Missing symptom reports, which were rare, were coded conservatively as the symptoms being absent. Missing information on AOO, which was rare, was imputed using regression-based imputation.

Other predictors of post-disaster PTSD

We examined four classes of predictors in addition to disaster characteristics and respondent history of psychopathology. The first were socio-demographics: age, education, and marital status, each defined as of the time of the disaster, and sex. Given its wide variation across countries, education was classified as low, low-average, high-average, or high (coded as a continuous 1–4 score) according to within-country norms. Details on this coding scheme are described elsewhere (Scott et al. 2014). Missing values, which were rare, were imputed using regression-based imputation. The next three classes of predictors assessed whether the respondent had been in one or more previous disasters, exposure to other lifetime TEs, and exposure to childhood family adversities (CAs). Consistent with prior WMH research (Kessler et al. 2010), we distinguished between CAs in a highly correlated set of seven we labelled Maladaptive Family Functioning (MFF) CAs (parental mental disorder, parental substance abuse, parental criminality, family violence, physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect) and other CAs (parental divorce, parental death, other parental loss, serious physical illness, family economic adversity). Details on CA measurement are presented elsewhere (Kessler et al. 2010). CAs that were examples of broader classes of TEs (e.g. sexual assaults perpetrated by a family member v. other sexual assaults) were included both in the TE inventory and the CA inventory in order to evaluate the incremental importance of exposure in the family context. Missing CA reports, which were rare, were coded conservatively as the CAs being absent.

Analysis methods

Each randomly-selected TE occurrence was weighted by the inverse of its probability of selection. For example, a respondent who reported three TE types and two occurrences of the randomly selected type would receive a TE weight of 6.0. The product of the Part II weight with the TE weight was used in our analyses, yielding a sample representative of all lifetime TEs occurring to all respondents. The sum of the consolidated weights across these respondents was standardized within each country to the observed number of respondents with the randomly selected disaster for purposes of pooled cross-national analysis.

Logistic regression was used to examine predictors of post-disaster PTSD pooled across surveys. Predictors were entered in blocks, beginning with socio-demographics, followed by disaster characteristics, prior TE and CA exposure, and prior mental disorders. All models included dummy control variables for surveys. Logistic regression coefficients and standard errors were exponentiated and are reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical significance of individual ORs was evaluated using 0.05-level two-sided tests based on the design-based Taylor-series method (Wolter, 1985) implemented in the SAS software system (SAS Institute Inc., 2008). Design-based F tests were used to evaluate significance of predictor sets, with numerator degrees of freedom equal to number of predictors and denominator degrees of freedom equal to number of geographically clustered sampling error calculation units containing randomly selected disasters across surveys (n = 138), minus the sum of primary sample units from which these sampling error calculation units were selected (n = 100) and one less than the number of variables in the predictor set (Reed, 2007), resulting in 38 denominator degrees of freedom in evaluating univariate predictions and fewer in evaluating multivariate predictions.

Once the final model was estimated, a predicted probability of PTSD was generated for each respondent from model coefficients. A receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve was calculated from these predicted probabilities (Zou et al. 2007) and area under the ROC curve (AUC) was calculated to quantify overall prediction accuracy (Hanley & McNeil, 1983). We then evaluated sensitivity and positive predictive value among the 5% of respondents with highest predicted probabilities to determine how well the model implies that subsequent PTSD could be predicted if the model was applied in the immediate aftermath of a future disaster. Sensitivity was the proportion of observed PTSD cases found among the 5% of respondents with highest predicted probabilities. Positive predictive value was the prevalence of PTSD among this 5% of respondents. We used the method of replicated 10-fold cross-validation with 20 replicates (i.e. 200 separate estimates of model coefficients) to correct for the over-estimation of prediction accuracy when both estimating and evaluating model fit in a single small sample (Smith et al. 2014).

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Results

Prevalence of disaster-related PTSD

Disaster exposure was the randomly selected TE for 661 respondents across the 18 surveys (Table 2). In 10 surveys, none of the respondents met DSM-IV/CIDI criteria for PTSD, while in the remaining eight surveys mean weighted PTSD prevalence was 2.5% (18 observed PTSD cases across surveys). Six of the latter eight surveys (accounting for 86.3% of respondents across all eight) were done in high-income countries and the other two in low-/middle-income countries. PTSD prevalence estimates were, on average, higher in the surveys in high- than low-/middle-income countries (2.8% v. 0.4%; t = 1.9, p = 0.051).

Table 2.

Prevalence of DSM-IV/CIDI disaster-related PTSD among respondents with randomly selected disasters by survey (n = 438)a

| % PTSD | (95% CI) | Number with PTSD (n1)b | Total sample size (n2)b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. High-income countries | ||||||

| Belgium | 0.5 | (0.0–1.7) | (1) | (7) | ||

| Italy | 3.8 | (0.0–11.2) | (1) | (35) | ||

| Northern Ireland | 0.5 | (0.0–1.5) | (1) | (23) | ||

| Spain | 0.1 | (0.0–0.2) | (1) | (14) | ||

| Spain – Murcia | 2.6 | (0.0–5.4) | (9) | (141) | ||

| United States | 3.4 | (0.0–8.0) | (3) | (158) | ||

| Total high | 2.8 | (0.5–5.1) | (16) | (378) | ||

| χ25c | 3.9 | p = 0.57 | ||||

| II. Middle- and low-income countries | ||||||

| Colombia | 0.5 | (0.0–1.5) | (1) | (21) | ||

| Mexico | 0.3 | (0.0–0.9) | (1) | (39) | ||

| Total low or middle | 0.4 | (0.0–0.9) | (2) | (60) | ||

| χ21c | 0.1 | p = 0.73 | ||||

| III. All countries | 2.5 | (0.5–4.4) | (18) | (438) | ||

| Overall between country difference − χ27c | 5.0 | p = 0.67 | ||||

| High v. low or middle difference − χ21c1 | 3.5 | p = 0.06 |

PTSD, Post-traumatic stress disorder; CI, confidence interval.

Each respondent who reported lifetime exposure to one or more traumatic experiences (TEs) had one occurrence of one such experience selected at random for detailed assessment. Each of these randomly selected TEs was weighted by the inverse of its probability of selection at the respondent level to create a weighted sample of TEs that was representative of all TEs in the population. The randomly selected disasters were the subset of these randomly selected TEs involving either natural or human-made disasters. The sum of weights of the randomly selected disasters was standardized within surveys to sum to the observed number of respondents whose randomly selected TE was a disaster. The n reported in the last column of this table represents that number of respondents. The results reported here are for the surveys where at least one respondent with a randomly selected disaster met DSM-IV/CIDI criteria for PTSD related to that TE. None of the respondents with randomly selected disasters in the other WMH surveys met criteria for disaster-related PTSD. These included 21 respondents in France 13 in Germany, 21 in Japan, 19 in Lebanon, 26 in Medellin, 11 in The Netherlands, 39 in Peru, 29 in Romania, 29 in South Africa, and 15 in Ukraine.

The reported sample sizes are unweighted. The unweighted proportions of respondents with PTSD do not match the prevalence estimates in the first column because the latter were based on weighted data.

The χ2 test with 5 degrees of freedom (df) in Part I of the table evaluated the significance of prevalence differences across the six high-income countries, while the 1 df test in Part II evaluated the prevalence difference between the two middle- and low-income countries. The two χ2 tests in Part III evaluated the significance of prevalence differences across all countries (the 7 df test) and between high- and middle-/low-income countries (the 1 df test). None of the tests are significant at the 0.05 level.

Predictors of disaster-related PTSD

The number of respondents with disaster-related PTSD in the two low-/middle-income countries was too small (n = 2 of n = 60 respondents) to estimate logistic regression equations separately. We consequently excluded low-/middle-income countries from further analysis. Median (interquartile range) number of years between the index disaster and the WMH interview in the remaining 6 surveys was 14 (3–35) years.

Model 1

Although respondent’s age and education at time of disaster both had significant positive univariate associations with disaster-related PTSD (age: OR 1.2, 95% CI 1.0–1.4; education: OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.1–3.9), neither association remained significant in the multivariate model (model 1) (Table 3). A methodological control for number of years between respondent’s age at disaster and age at interview to investigate the possibility of time-related recall bias added to the model was non-significant (OR 1.4, 95% CI 0.8–2.2).

Table 3.

Associations of socio-demographics, disaster characteristics, and prior vulnerabilities with DSM-IV/CIDI disaster-related PTSD (n = 378)a

| Univariate Modelb

|

Model 1

|

Model 2

|

Model 3

|

Model 4

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| I. Socio-demographics | ||||||||||

| Age at disaster (in decades) | 1.2* | (1.0–1.4) | 1.4 | (0.9–2.1) | 1.8 | (1.0–3.2) | 1.4 | (0.7–2.6) | 0.9 | (0.3–3.0) |

| Gender (female) | 1.0 | (0.3–4.1) | 1.4 | (0.3–5.6) | 0.9 | (0.2–3.8) | 1.4 | (0.5–3.5) | 0.9 | (0.3–2.8) |

| Educationc | 2.1* | (1.1–3.9) | 2.7 | (0.9–8.0) | 2.7 | (0.7–10.8) | 3.2 | (0.8–12.4) | 2.5* | (1.5–4.2) |

| Ever married | 0.8 | (0.2–2.8) | 0.2 | (0.0–3.9) | 0.1 | (0.0–1.3) | 0.2* | (0.0–0.6) | 0.2 | (0.0–1.2) |

| II. Disaster characteristics | ||||||||||

| Human-made v. natural disaster | 5.3* | (1.4–19.3) | – | – | 3.3* | (1.1–9.7) | 2.9* | (1.3–6.7) | 3.1 | (0.9–10.0) |

| Serious injury to respondent | 8.6* | (2.2–33.9) | – | – | 0.6 | (0.1–3.0) | 0.6 | (0.1–6.6) | 0.3 | (0.0–2.4) |

| Respondent witnessed death | 6.4 | (0.4–108.2) | – | – | 1.3 | (0.0–57.0) | 1.2 | (0.2–6.6) | 0.3 | (0.1–1.5) |

| Serious injury/death of loved one | 15.3* | (1.6–143.1) | – | – | 21.5* | (2.1–222.8) | 88.2* | (13.0–596.7) | 165.9* | (26.7–1031.0) |

| Respondent displaced from home | 4.3 | (0.8–22.9) | – | – | 6.6* | (1.9–22.3) | 9.3* | (5.1–16.9) | 6.2* | (3.2–12.2) |

| III. Prior vulnerability actors | ||||||||||

| Any prior traumatic violent experienced | 7.7* | (3.3–18.0) | – | – | – | – | 16.4* | (2.6–101.6) | 5.0* | (1.2–21.5) |

| Count of childhood adversitiese | 2.2* | (1.2–4.0) | – | – | – | – | 2.9* | (1.4–6.2) | 3.6* | (2.0–6.7) |

| Prior mental disorders | ||||||||||

| Exactly 1 | 1.7 | (0.5–6.5) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 9.8 | (0.5–192.4) |

| 2+ | 38.4* | (15.5–95.0) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 60.0* | (21.1–170.5) |

| F(2,37)f | 214.1* | p < 0.001 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 52.5* | p < 0.001 |

| F(5,35), (9,30), (11,28), (13,26)g | – | – | 1.9 | p = 0.14 | 72.3* | p < 0.001 | 69.9* | p < 0.001 | 133.1* | p < 0.001 |

PTSD, Post-traumatic stress disorder; OR, Odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

All models were estimated in weighted data pooled across the six surveys in high-income countries. See Table note a in Table 2 for a description of the weighting. All models included dummy variable controls for surveys. This means that the reported ORs should be interpreted as pooled within-survey coefficients.

The univariate associations are based on a separate model for each row, with the variable in the row and the dummy controls for survey the only predictors in the model.

Education was treated as a continuous variable coded 1–4 (low, low-average, high-average, high).

Any prior traumatic violent experience includes exposure to any of four types of organized violence (e.g. civilian in a war zone, relief worker in a war zone, refugee); three types of interpersonal violence (witnessed violence at home as a child, beaten by a caregiver as a child, beaten by someone else other than a romantic partner); and seven types of sexual violence (e.g. raped, sexually assaulted, beaten by a romantic partner).

A count in the range 0–3+ of maladaptive family functioning childhood adversities experienced by the respondent in childhood from a total of seven assessed in the surveys that included parental mental disorder, parental substance abuse, parental criminality, family violence, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and physical neglect.

The joint significance of the pair of dummy variables for number of mental disorders.

The joint significance of all variables in the model. The numerator and denominator degrees of freedom are, respectively, the number of predictors in the model and the residual number of sampling error calculation units.

Significant at the 0.05 level, two-sided test.

Model 2

Human-made disasters (reported by 26.6% of respondents) were associated with significantly higher odds of PTSD than natural disasters (OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.1–9.7) in the multivariate model of disaster characteristics (model 2). Serious injury or death of someone close (reported by 4.3% of respondents) was also a significant predictor (OR 21.5, 95% CI 2.1–222.8), although the wide CI and much higher OR than in the univariate model signalled model instability. Being displaced by the disaster (reported by 27.8% of respondents) was also a significant predictor in the multivariate model (OR 6.6, 95% CI 1.9–22.3) even though it was not significant in the univariate model. Serious injury to the respondent (reported by 1.1% of respondents), while a significant univariate predictor, was not significant in the multivariate model. Finally, the respondent witnessing death (reported by 7.8% of respondents) was not a significant univariate or multivariate predictor.

Model 3

Preliminary analysis of associations of prior TEs with disaster-related PTSD showed prior TEs involving exposure to sectarian, interpersonal, or sexual violence were the only ones consistently associated with increased risk of disaster-related PTSD controlling model 3 predictors. (See supplementary material.) The most parsimonious characterization of these associations used a single dichotomous variable for whether the respondent was previously exposed to any such TE (reported by 25.1% of respondents; OR 16.4, 95% CI 2.6–101.6). Preliminary analysis of the associations of CAs with disaster-related PTSD showed numerous significant positive univariate associations that could best be summarized with a 0–3+ count for number of MFF CAs (15.4%, 1; 6.5%, 2; 13.3% 3+; OR 2.9, 95% CI 1.4–6.2). (See supplementary material.) The multivariate ORs of both TEs and CAs were larger than the univariate ORs and had wide CIs. In addition, the OR of serious injury/death of someone close became markedly higher in model 3 than model 2.

Model 4

Preliminary analysis showed that 13 of the 14 temporally primary lifetime DSM-IV/CIDI disorders had elevated univariate ORs predicting disaster-related PTSD (11 of them significant at the 0.05 level), but that only a handful were significant in a multivariate model due to high co-morbidity. (See supplementary material online.) The most parsimonious characterization of these associations used dummy variables for exactly 1 (17.6%, OR 9.8, 95% CI 0.5–192.4) and 2+ (14.1%, OR 60.0, 95% CI 21.1–170.5) prior lifetime DSM-IV/CIDI disorders as predictors. The significant OR of prior lifetime TEs in model 3 decreased substantially, while the significant OR of serious injury or death of someone close to the respondent increased substantially when mental disorders were controlled in model 4 compared to model 3.

Strength and consistency of overall model predictions

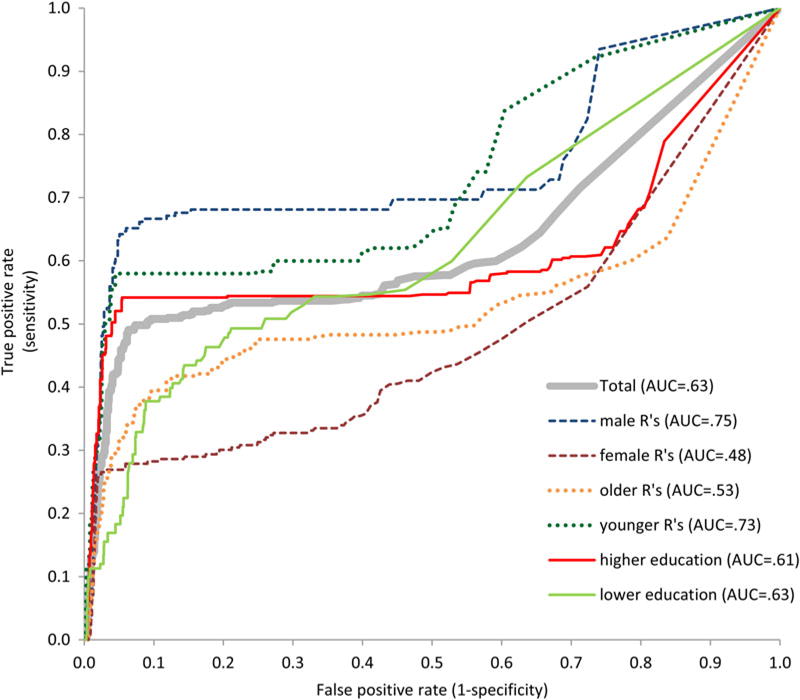

Although the small sample size precluded estimating model coefficients separately in each survey, we could compare overall model fit in subsamples by calculating individual-level predicted probabilities from model 4 with 20 replicates of 10-fold cross-validation, estimating subsample ROC curves from these predicted probabilities, and calculating AUC based on these curves. Estimated AUC based on 20 replicates of 10-fold cross-validated predictions was 0.63 in the total sample and 0.48–0.75 in subsamples defined by respondent’s sex, age, and education. These are weak to intermediate levels of overall classification accuracy (Roemer et al. 1998). However, the 5% of respondents with highest predicted probabilities of PTSD included a substantial proportion (44.5%) of all disaster-related PTSD (sensitivity) in the total sample. This is nine times the concentration of risk expected by chance (Table 4). Subgroup sensitivities among this 5% of respondents with highest predicted risk ranged from 56.4% among men to 22.4% among respondents with low-average/low education. Positive predictive value (the proportion of predicted positives who met criteria for PTSD) among the 5% of respondents with higher predicted risk was 20.4% in the total sample and between 39.5% among respondents with high-average/high education to 3.9% among respondents with low-average/low education (Fig. 1).

Table 4.

Concentration of risk of observed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the top 5th percentile of predicted PTSD, total sample and stratified by subgroups (n = 378)a

| Sensitivityb

|

Positive predictive valuec

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % PTSD | (S.E.) | % PTSD | (S.E.) | |

| Total | 44.5 | (18.0) | 20.4 | (9.5) |

| Age | ||||

| 25+ years | 34.0 | (13.6) | 11.8 | (1.3) |

| <25 years | 52.9 | (26.3) | 32.4 | (20.7) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 56.4 | (24.3) | 29.4 | (19.6) |

| Female | 27.9 | (23.8) | 10.9 | (8.8) |

| Education | ||||

| High or high-average | 50.3 | (20.3) | 39.5 | (16.4) |

| Low or low-average | 22.4 | (14.9) | 3.9 | (0.5) |

Based on weighted data pooled across the six surveys in high-income countries. See Table note a in Table 2 for a description of the weighting. Ten-fold cross-validation involves dividing the sample into 10 separate random subsamples of equal size, estimating the model in each of the 10 separate 90% subsamples created by deleting one of the 10 subsamples, and applying predicted values based on each set of coefficients only to the remaining 10% of the sample. Replicated cross-validation involves repeating the cross-validation process some number of times (20 times in the current application), with a different random split of the sample into 10 equal-sized subsamples each time. Sensitivity and positive predictive value were calculated separately in each of these 200 subsamples and averaged to produce the results reported here.

Sensitivity = proportion of all PTSD found among the 5% of respondents with highest predicted probabilities based on the final model.

Positive predictive value = prevalence of PTSD among respondents in the row who are among the 5% in the total sample with the highest predicted probabilities based on the final model.

Fig. 1.

Area under the curve (AUC) of predicted probabilities based on model 4 overall and in selected subgroups.

Discussion

Several limitations should be noted. First, several surveys had unacceptably low response rates. Second, TEs and mental disorders were assessed retrospectively, although special recall probes used in WMH surveys have been shown experimentally to improve retrospective recall accuracy (Knauper et al. 1999). Third, diagnoses were based on a fully structured lay-administered interview rather than semi-structured clinical interviews, although WMH clinical appraisal data are reassuring (Haro et al. 2006). Fourth, given that disasters were only one of many TEs assessed in the WMH surveys, information on potentially important predictors of post-disaster PTSD was much more limited than in surveys focused exclusively on disaster survivors.

The sampling restrictions are of special importance. The vast majority of disasters occur in low- and middle-income countries (Roy et al. 2011), but our analyses were carried out exclusively in high-income countries. In addition, the samples were restricted to household residents. This means that we excluded people living in displacement camps and other group quarters, which is an especially serious limitation given that displacement was a significant predictor of disaster-related PTSD. While the 378 respondents assessed for randomly selected disasters is sufficient to estimate prevalence of post-disaster PTSD with good precision, the fact that PTSD was an uncommon outcome (n = 16) meant that we lacked statistical power to estimate multivariate predictor coefficients with precision. Indeed, with 13 model coefficients, the 1.2 events-per-variable (EPV) ratio was well below the value recommended to avoid biased OR estimates (Peduzzi et al. 1996). Caution is consequently needed in interpreting our results because of low EPV and the clear evidence of model instability noted in Table 3.

Despite these limitations, our study is valuable in providing the first cross-national data on prevalence of disaster-related PTSD among household residents. Results are clear across countries that post-disaster PTSD is uncommon. This is consistent with previous general population surveys on post-disaster PTSD in Europe (Ferry et al. 2014; Olaya et al. 2015) and the United States (Kessler et al. 1995; Breslau et al. 1998, 2013). As noted in the Introduction, disaster-focused studies, which are typically carried out between 1 month and 2 years after disasters, generally yield considerably higher prevalence estimates, presumably because of unrepresentative samples and demand characteristics, although another consideration is that these studies tend to be carried out primarily in conjunction with the most severe disasters.

The most important predictors in our study were generally consistent with those found in previous post-disaster studies (Galea et al. 2005): prior psychopathology, disaster severity, and history of previous trauma. This adds support to the recommendation of North & Pfefferbaum (2013) to include information about these three classes of risk factors in needs assessment surveys of disaster survivors. It is also noteworthy that several previous epidemiological studies found, consistent with our result, that human-made disasters have more pernicious psychological effects than natural disasters (Galea et al. 2005), although this association became much less pronounced when we controlled for disaster-related characteristics, suggesting that at least part of the reason human-made disasters are associated with higher rates of PTSD than natural disasters is that the former are objectively more severe. Caution is needed in interpreting this result, though, as an exploratory factor analysis of TEs in an earlier WMH report found that the human-made disasters reported in the WMH surveys include a mix of accidents caused by human error and motivated acts of terrorism (Benjet et al. 2016). We have no way of distinguishing these two types of human-made disasters to determine if they have similar associations with PTSD.

Perhaps our most striking result was that nearly half of disaster-related PTSD occurred among the 5% of respondents with highest predicted risk scores in our model. This result is broadly consistent with several other recent studies showing that subsequent PTSD can be predicted with good accuracy using data collected in the immediate aftermath of trauma about pre-trauma risk factors, objective trauma characteristics, and early post-traumatic responses (Galatzer-Levy et al. 2014; Kessler et al. 2014; Karstoft et al. 2015). These findings contradict the previously-held view that the individual predictors in epidemiological models of PTSD have ORs too weak and inconsistent to be clinically useful in targeting people for preventive interventions (Brewin, 2005a), making it necessary to use assessment tools in the aftermath of trauma focused on current symptoms rather than risk factors (Brewin, 2005b). The error in this earlier way of thinking was in failing to appreciate that multivariate model-based predictions can be strong even when coefficients of individual predictors are weak. It is noteworthy in this regard that our high concentration of PTSD risk among the 5% of respondents with highest predicted risk from our model was based on a replicated cross-validated simulation designed to adjust for over-fitting due to low EPV.

The evidence we found for high concentration of risk based on our model suggests that future research is needed both to create an assessment tool for use in the aftermath of disasters to measure key risk factors (i.e. disaster-related experiences, prior exposures to highly stressful experiences, and prior history of mental disorders) and to develop a prediction model that uses this information to generate individual-level PTSD risk scores to target high-risk survivors for preventive interventions. While the WMH results provide strong suggestive evidence that a useful model of this sort could be developed from self-report data, the WMH model itself is inadequate because it was based on coarse measures assessed retrospectively in a small sample.

At the same time, the WMH results were sufficiently consistent with prior evidence that one could imagine a triage screening system being developed that was based loosely on these consistent risk factors. This is the approach taken in the PsySTART system recently adopted by the American Red Cross to target rapid delivery of psychological first aid and referral for mental health services to disaster survivors judged to be at high risk of post-disaster mental disorders in the immediate aftermath of a disaster (Schreiber et al. 2014). PsySTART is different from previous post-disaster risk evaluation schemes in that it does not focus on current psychological distress (other than acute suicidality), which is an unreliable predictor of post-disaster mental disorders (Norris et al. 2002), but on evidence-based predictors of those disorders (disaster-related experiences, prior disaster exposure, prior trauma exposure, and history of prior mental disorders) evaluated by trained Red Cross disaster mental health workers.

The approach proposed here could be seen as a next step in the PsySTART program designed to refine the selection of risk factors and optimize the weighting scheme used to combine information about these risk factors into a composite risk score. These refinements would require data to be collected from a much larger sample than in the WMH analysis. The sample should include a baseline assessment of a broad range of risk factors obtained in the immediate aftermath of disaster. Participants should be followed over time to determine who develops PTSD or other post-disaster mental disorders. Much more sophisticated data analysis methods should be used to analyse these data than in the WMH analysis. In particular, machine learning methods designed to maximize out-of-sample prediction accuracy should be used to develop the final model (Kessler et al. 2014), leading to optimal selection of the risk factors to include in subsequent assessments and to optimal weighting of these measures to assess risk of post-disaster psychopathology. We were unable to use these methods in the WMH analysis because of our small sample size. Given the growing literature documenting the value of interventions in the immediate aftermath of trauma (Forneris et al. 2013; Kliem & Kroger, 2013; Amos et al. 2014; Bisson, 2014), the development of such an optimal prediction model could be of great practical value.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; R01 MH070884 and R01 MH093612-01), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01-DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R03-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. We thank the staff of the WMH Data Collection and Data Analysis Coordination Centres for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and consultation on data analysis. None of the funders had any role in the design, analysis, interpretation of results, or preparation of this paper. The Colombian National Study of Mental Health (NSMH) is supported by the Ministry of Social Protection. The Mental Health Study Medellín – Colombia was carried out and supported jointly by the Center for Excellence on Research in Mental Health (CES University) and the Secretary of Health of Medellín. The ESEMeD project is funded by the European Commission (Contracts QLG5-1999-01042; SANCO 2004123, and EAHC 20081308), the Piedmont Region (Italy), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain (FIS 00/0028), Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spain (SAF 2000-158-CE), Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CIBER CB06/02/0046, RETICS RD06/0011 REM-TAP), and other local agencies and by an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline. The World Mental Health Japan (WMHJ) Survey is supported by the Grant for Research on Psychiatric and Neurological Diseases and Mental Health (H13-SHOGAI-023, H14-TOKUBETSU-026, H16-KOKORO-013) from the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The Lebanese National Mental Health Survey (L.E.B.A.N.O.N.) is supported by the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health, the WHO (Lebanon), National Institute of Health/Fogarty International Center (R03 TW006481-01), Sheikh Hamdan Bin Rashid Al Maktoum Award for Medical Sciences, anonymous private donations to IDRAAC, Lebanon, and unrestricted grants from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Hikma Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Novartis, and Servier. The Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (MNCS) is supported by The National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente (INPRFMDIES 4280) and by the National Council on Science and Technology (CONACyT-G30544- H), with supplemental support from the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). The Northern Ireland Study of Mental Health was funded by the Health & Social Care Research & Development Division of the Public Health Agency. The Peruvian World Mental Health Study was funded by the National Institute of Health of the Ministry of Health of Peru. The Romania WMH study projects ‘Policies in Mental Health Area’ and ‘National Study regarding Mental Health and Services Use’ were carried out by National School of Public Health & Health Services Management (former National Institute for Research & Development in Health), with technical support of Metro Media Transylvania, the National Institute of Statistics-National Centre for Training in Statistics, SC. Cheyenne Services SRL, Statistics Netherlands, and were funded by Ministry of Public Health (former Ministry of Health) with supplemental support of Eli Lilly Romania SRL. The Psychiatric Enquiry to General Population in Southeast Spain – Murcia (PEGASUS-Murcia) Project has been financed by the Regional Health Authorities of Murcia (Servicio Murciano de Salud and Consejería de Sanidad y Política Social) and Fundación para la Formación e Investigación Sanitarias (FFIS) of Murcia. The South Africa Stress and Health Study (SASH) is supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH059575) and National Institute of Drug Abuse with supplemental funding from the South African Department of Health and the University of Michigan. The Ukraine Comorbid Mental Disorders during Periods of Social Disruption (CMDPSD) study is funded by the US National Institute of Mental Health (RO1-MH61905). The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044708), and the John W. Alden Trust. A complete list of all within-country and cross-national WMH publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/.

Appendix. The WHO World Mental Health Survey Collaborators

Tomasz Adamowski, Ph.D., M.D., Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola, M.D., Ph.D., Ali Al-Hamzawi, M.D., Mohammad Al-Kaisy, M.D., Abdullah Al Subaie, FRCP, Jordi Alonso, M.D., Ph.D., Yasmin Altwaijri, MS, Ph.D., Laura Helena Andrade, M.D., Ph.D., Lukoye Atwoli, M.D., Randy Auerbach, Ph.D., William Axinn, Ph.D., Corina Benjet, Ph.D., Guilherme Borges, ScD, Robert Bossarte, Ph.D., Evelyn J. Bromet, Ph.D., Ronny Bruffaerts, Ph.D., Brendan Bunting, Ph.D., Ernesto Caffo, M.D., Jose Miguel Caldas-de -Almeida, M.D., Ph.D., Graca Cardoso, M.D., Ph.D., Alfredo H. Cia, M.D., Stephanie Chardoul, Somnath Chatterji, M.D., Alexandre Chiavegatto Filho, Ph.D., Pim Cuijpers, Ph.D., Louisa Degenhardt, Ph.D., Giovanni de Girolamo, M.D., Ron de Graaf, MS, Ph.D., Peter de Jonge, Ph.D., Koen Demyttenaere, M.D., Ph.D., David Ebert, Ph.D., Sara Evans-Lacko, Ph.D., John Fayyad, M.D., Marina Piazza Ferrand, DSc, MPH, Fabian Fiestas, M.D., Ph.D., Silvia Florescu, M.D., Ph.D., Barbara Forresi, Ph.D., Sandro Galea, DrPH, M.D., MPH, Laura Germine, Ph.D., Stephen Gilman, ScD, Dirgha Ghimire, Ph.D., Meyer Glantz, Ph.D., Oye Gureje, M.D., Ph.D., Josep Maria Haro, M.D., MPH, Ph.D., Yanling He, M.D., Hristo Hinkov, M.D., Chi-yi Hu, Ph.D., M.D., Yueqin Huang, M.D., MPH, Ph.D., Aimee Nasser Karam, Ph.D., Elie G. Karam, M.D., Norito Kawakami, M.D., Ph.D., Ronald C. Kessler, Ph.D., Andrzej Kiejna, Ph.D., M.D., Karestan Koenen, Ph.D., Viviane Kovess-Masfety, MS, M.D., Ph.D., Luise Lago, Ph.D., Carmen Lara, M.D., Ph.D., Sing Lee, Ph.D., Jean-Pierre Lepine, M.D., Itzhak Levav, M.D., Daphna Levinson, Ph.D., Zhaorui Liu, M.D., MPH, Silvia Martins, M.D., Ph.D., Herbert Matschinger, Ph.D., John McGrath, Ph.D., Katie A. McLaughlin, Ph.D., Maria Elena Medina-Mora, Ph.D., Zeina Mneimneh, Ph.D., MPH, Jacek Moskalewicz, DrPH, Samuel Murphy, DrPH, Fernando Navarro-Mateu, M.D., Ph.D., Matthew K. Nock, Ph.D., Siobhan O’Neill, Ph.D., Mark Oakley-Browne, MB, ChB, Ph.D., J. Hans Ormel, Ph. D., Beth-Ellen Pennell, MA, Stephanie Pinder-Amaker, Ph.D., Patryk Piotrowski, M.D., Ph.D., Jose Posada-Villa, M.D., Ayelet Ruscio, Ph.D., Kate Scott, Ph.D., Vicki Shahly, Ph.D., Derrick Silove, Ph.D., Tim Slade, Ph.D., Jordan Smoller, ScD, M.D., Juan Carlos Stagnaro, M.D., Ph.D., Dan J. Stein, MBA, MSc, Ph.D., Amy Street, Ph.D., Hisateru Tachimori, Ph.D., Nezar Taib, MS, Margreet ten Have, Ph.D., Graham Thornicroft, Ph.D., Yolanda Torres de Galvis, MPH, Maria Carmen Viana, M.D., Ph.D., Gemma Vilagut, MS, Elisabeth Wells, Ph.D., David R. Williams, MPH, Ph.D., Michelle Williams, ScD, Bogdan Wojtyniak, ScD, Alan M. Zaslavsky, Ph.D.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

In the past 3 years, Dr Kessler has served as a consultant for or received research support from Johnson & Johnson Wellness and Prevention, the Lake Nona Life Project, and Shire Pharmaceuticals. Dr Kessler is a co-owner of DataStat, Inc., a market research company that carries out healthcare research. The other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716002026.

References

- Amos T, Stein DJ, Ipser JC. Pharmacological interventions for preventing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;7:CD006239. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006239.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Bromet E, Karam EG, Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Ruscio AM, Shahly V, Stein DJ, Petukhova M, Hill E, Alonso J, Atwoli L, Bunting B, Bruffaerts R, Caldas-de-Almeida JM, de Girolamo G, Florescu S, Gureje O, Huang Y, Lepine JP, Kawakami N, Kovess-Masfety V, Medina-Mora ME, Navarro-Mateu F, Piazza M, Posada-Villa J, Scott KM, Shalev A, Slade T, ten Have M, Torres Y, Viana MC, Zarkov Z, Koenen KC. The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychological Medicine. 2016;46:327–343. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisson JI. Early responding to traumatic events. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;204:329–330. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.136077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Brewin CR, Kaniasty K, La Greca AM. Weighing the costs of disaster: consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2010;11:1–49. doi: 10.1177/1529100610387086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:626–632. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Troost JP, Bohnert K, Luo Z. Influence of predispositions on post-traumatic stress disorder: does it vary by trauma severity? Psychological Medicine. 2013;43:381–390. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR. Risk factor effect sizes in PTSD: what this means for intervention. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2005a;6:123–130. doi: 10.1300/J229v06n02_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR. Systematic review of screening instruments for adults at risk of PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005b;18:53–62. doi: 10.1002/jts.20007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromet EJ, Hobbs MJ, Clouston SA, Gonzalez A, Kotov R, Luft BJ. DSM-IV post-traumatic stress disorder among World Trade Center responders 11–13 years after the disaster of 11 September 2001 (9/11) Psychological Medicine. 2016;46:771–783. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darves-Bornoz JM, Alonso J, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Haro JM, Kovess-Masfety V, Lepine JP, Nachbaur G, Negre-Pages L, Vilagut G, Gasquet I. Main traumatic events in Europe: PTSD in the European study of the epidemiology of mental disorders survey. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:455–462. doi: 10.1002/jts.20357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Boden JM, Mulder RT. Impact of a major disaster on the mental health of a well-studied cohort. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:1025–1031. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry F, Bunting B, Murphy S, O’Neill S, Stein D, Koenen K. Traumatic events and their relative PTSD burden in Northern Ireland: a consideration of the impact of the ‘Troubles’. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2014;49:435–446. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0757-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams BJ. Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders. New York State Psychiatric Institute Biometrics Research Department; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Forneris CA, Gartlehner G, Brownley KA, Gaynes BN, Sonis J, Coker-Schwimmer E, Jonas DE, Greenblatt A, Wilkins TM, Woodell CL, Lohr KN. Interventions to prevent post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44:635–650. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galatzer-Levy IR, Karstoft KI, Statnikov A, Shalev AY. Quantitative forecasting of PTSD from early trauma responses: a machine learning application. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2014;59:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Nandi A, Vlahov D. The epidemiology of post-traumatic stress disorder after disasters. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2005;27:78–91. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxi003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner M, Altman D. Statistics with Confidence: Confidence Intervals and Statistical Guidelines. BMJ Books; London: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Goldmann E, Galea S. Mental health consequences of disasters. Annual Review of Public Health. 2014;35:169–183. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology. 1983;148:839–843. doi: 10.1148/radiology.148.3.6878708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness J, Pennell B-P, Villar A, Gebler N, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Bilgen I. Translation procedures and translation assessment in the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. In: Kessler RC, Ustun TB, editors. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2008. pp. 91–113. [Google Scholar]

- Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, de Girolamo G, Guyer ME, Jin R, Lepine JP, Mazzi F, Reneses B, Vilagut G, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2006;15:167–180. doi: 10.1002/mpr.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa SG, Wells EJ, Hubbard F, Mneimneh ZN, Chiu WT, Sampson NA, Berglund PA. Sample designs and sampling procedures. In: Kessler RC, Ustun TB, editors. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2008. pp. 14–32. [Google Scholar]

- Karstoft KI, Galatzer-Levy IR, Statnikov A, Li Z, Shalev AY. Bridging a translational gap: using machine learning to improve the prediction of PTSD. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:30. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0399-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Akiskal HS, Angst J, Guyer M, Hirschfeld RM, Merikangas KR, Stang PE. Validity of the assessment of bipolar spectrum disorders in the WHO CIDI 3.0. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;96:259–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alhamzawi AO, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Benjet C, Bromet E, Chatterji S, de Girolamo G, Demyttenaere K, Fayyad J, Florescu S, Gal G, Gureje O, Haro JM, Hu CY, Karam EG, Kawakami N, Lee S, Lepine JP, Ormel J, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Tsang A, Ustun TB, Vassilev S, Viana MC, Williams DR. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. British Journal of Psychiatry: the Journal of Mental Science. 2010;197:378–385. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Rose S, Koenen KC, Karam EG, Stang PE, Stein DJ, Heeringa SG, Hill ED, Liberzon I, McLaughlin KA, McLean SA, Pennell BE, Petukhova M, Rosellini AJ, Ruscio AM, Shahly V, Shalev AY, Silove D, Zaslavsky AM, Angermeyer MC, Bromet EJ, de Almeida JM, de Girolamo G, de Jonge P, Demyttenaere K, Florescu SE, Gureje O, Haro JM, Hinkov H, Kawakami N, Kovess-Masfety V, Lee S, Medina-Mora ME, Murphy SD, Navarro-Mateu F, Piazza M, Posada-Villa J, Scott K, Torres Y, Carmen Viana M. How well can post-traumatic stress disorder be predicted from pre-trauma risk factors? An exploratory study in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:265–274. doi: 10.1002/wps.20150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliem S, Kroger C. Prevention of chronic PTSD with early cognitive behavioral therapy. A meta-analysis using mixed-effects modeling. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2013;51:753–761. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knauper B, Cannell CF, Schwarz N, Bruce ML, Kessler RC. Improving accuracy of major depression age-of-onset reports in the US National Comorbidity Survey. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1999;8:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes AP, Macedo TF, Coutinho ES, Figueira I, Ventura PR. Systematic review of the efficacy of cognitive-behavior therapy related treatments for victims of natural disasters: a worldwide problem. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e109013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar BE, Buka SL, Kessler RC. Child sexual abuse and subsequent psychopathology: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:753–760. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neria Y, Nandi A, Galea S. Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: a systematic review. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:467–480. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, Byrne CM, Diaz E, Kaniasty K. 60,000 disaster victims speak: part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65:207–239. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Galea S, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ. Methods for Disaster Mental Health Research. Guilford Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- North CS. Current research and recent breakthroughs on the mental health effects of disasters. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2014;16:481. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0481-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North CS, Pfefferbaum B. Mental health response to community disasters: a systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;310:507–518. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.107799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olaya B, Alonso J, Atwoli L, Kessler RC, Vilagut G, Haro JM. Association between traumatic events and post-traumatic stress disorder: results from the ESEMeD-Spain study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 2015;24:172–183. doi: 10.1017/S2045796014000092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR, Feinstein AR. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1996;49:1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed JFI. Better binomial confidence intervals. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods. 2007;6:153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Roemer L, Litz BT, Orsillo SM, Ehlich PJ, Friedman MJ. Increases in retrospective accounts of war-zone exposure over time: the role of PTSD symptom severity. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1998;11:597–605. doi: 10.1023/A:1024469116047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy N, Thakkar P, Shah H. Developing-world disaster research: present evidence and future priorities. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2011;5:112–116. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2011.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS Software Version 9.2. SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sayed S, Iacoviello BM, Charney DS. Risk factors for the development of psychopathology following trauma. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2015;17:612. doi: 10.1007/s11920-015-0612-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber MD, Yin R, Omaish M, Broderick JE. Snapshot from Superstorm Sandy: American Red Cross mental health risk surveillance in lower New York State. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2014;64:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KM, Al-Hamzawi AO, Andrade LH, Borges G, Caldas-de-Almeida JM, Fiestas F, Gureje O, Hu C, Karam EG, Kawakami N, Lee S, Levinson D, Lim CC, Navarro-Mateu F, Okoliyski M, Posada-Villa J, Torres Y, Williams DR, Zakhozha V, Kessler RC. Associations between subjective social status and DSM-IV mental disorders: results from the World Mental Health surveys. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:1400–1408. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GC, Seaman SR, Wood AM, Royston P, White IR. Correcting for optimistic prediction in small data sets. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2014;180:318–324. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. Data: Countries and Economies. The World Bank Group; Washington, DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Warsini S, West C, Ed Tt GD, Res Meth GC, Mills J, Usher K. The psychosocial impact of natural disasters among adult survivors: an integrative review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2014;35:420–436. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2013.875085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter KM. Introduction to Variance Estimation. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zou KH, O’Malley AJ, Mauri L. Receiver-operating characteristic analysis for evaluating diagnostic tests and predictive models. Circulation. 2007;115:654–657. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.