Abstract

Retrobulbar injection has been widely practiced as a technique of ocular anesthesia for many decades. Nevertheless, the technique is not free from complications. Vascular occlusion secondary to retrobulbar injection is rare but can be vision threatening. We report a case series of two such patients who presented with poor vision following retrobulbar injection. Fundus showed pale retina with cherry red spot suggestive of central retinal artery occlusion in case 1 and pale disc with sclerosed vessels and multiple superficial hemorrhages suggestive of a combined occlusion of retinal artery and vein in case 2. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed thickened inner retinal layers with intact outer retinal layers in case 1 and thinning in case 2. We conclude that retrobulbar injections can rarely be associated with dreadful vision-threatening complications like in our patients. We also report the role of OCT in assessing the prognosis following vascular occlusion.

Keywords: Combined occlusion, retrobulbar injection, vascular occlusion

Introduction

Retrobulbar injection has been the most commonly employed technique of ocular anesthesia for many decades. As the technique is quick and efficient and requires lesser volume of anesthetic agent than other techniques, it is very popular in most developing countries like India, where cataract surgeries are being done in large numbers. Nevertheless, the technique is not free from complications. Retrobulbar hemorrhage, globe perforation, and central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) are some of its vision-threatening complications; inadvertent injection of the drug into the optic nerve can rarely result in central nervous system complications that can be life threatening. We report two cases of retinal vascular occlusions that developed immediately following retrobulbar injection.

Case Report

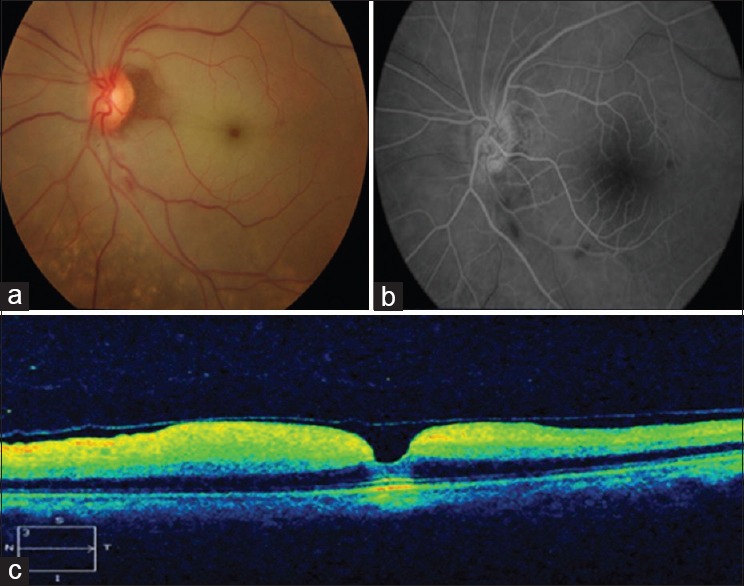

Our first patient was a 65-year-old female who experienced poor vision OS on the 1st postoperative day of an uneventful manual small incision cataract surgery performed under retrobulbar anesthesia at our institute. She was a known diabetic and hypertensive patient but had no history of cardiac illness. Vision OS was perception of light. Intraocular pressure (IOP) was 20 mmHg. Anterior segment was unremarkable except for relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD). Fundus revealed marked retinal whitening in the macular region with cherry red spot suggestive of CRAO [Figure 1a]. Clinically, there was no evidence of retrobulbar hemorrhage or globe perforation. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD OCT) was performed to confirm the diagnosis [Figure 1c]. She was treated with ocular massage and anterior chamber paracentesis along with IOP-reducing agents. Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) was done on the next day to assess the retinal perfusion [Figure 1b]. Her best-corrected visual acuity was counting fingers (CFs) at 5 m at 1-month follow-up visit.

Figure 1.

Central retinal artery occlusion. (a) Fundus picture showing retinal whitening in the posterior pole with cherry red spot suggestive of central retinal artery occlusion, (b) fundus fluorescein angiography taken on the next day showing normal arm retinal time with delayed arterio-venous time suggestive of reperfusion, (c) optical coherence tomography shows hyperreflective inner retinal layers with thickening and an intact outer retina suggestive of central retinal artery occlusion. Inner retinal layers are edematous and fused due to an acute ischemic event

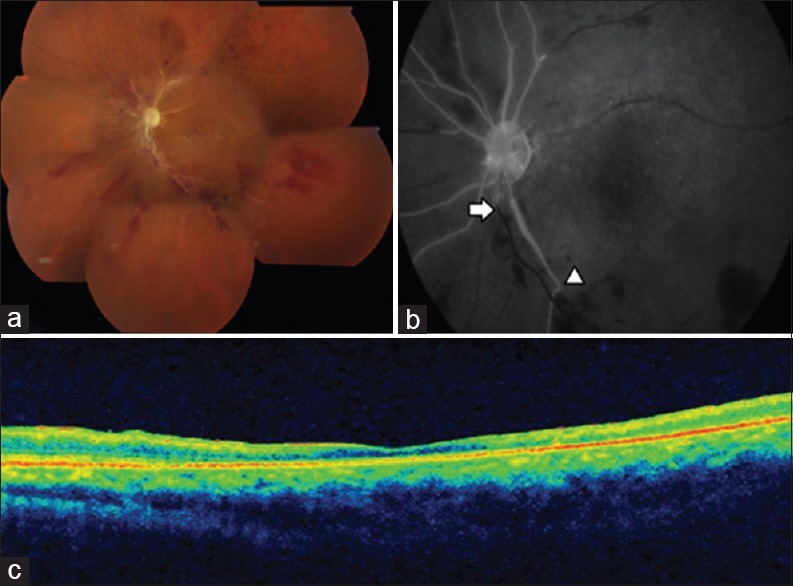

Our second patient was a 46-year-old female who was referred to our institute with complaints of vision worsening following OS cataract surgery. Retrospectively, we found that she had undergone uneventful cataract surgery under retrobulbar anesthesia, a month ago. She was not a known diabetic, hypertensive, or cardiac patient. Vision was CFs at 1 m. IOP was 12 mmHg. Anterior segment was unremarkable except for RAPD. Fundus revealed pale disc, sclerosed arteries, and veins with superficial hemorrhages, suggestive of a long-standing combined occlusion of central retinal artery and vein [Figure 2a]. FFA confirmed the diagnosis [Figure 2b]. SD OCT showed thinning and atrophy of inner retinal layers, suggestive of a long-standing arterial occlusion [Figure 2c]. Her vision remained the same at 1-month follow-up visit. Laboratory workup and cardiac assessment of both patients were found to be within normal limits.

Figure 2.

Combined occlusion of central retinal artery and vein. (a) Fundus image (montage) shows pale disc, sclerosed vessels, and intraretinal hemorrhages in all quadrants suggestive of combined occlusion, (b) fundus fluorescein angiography shows occluded artery (arrow head) and occluded vein (arrow), (c) optical coherence tomography shows thin and atrophic retinal layers suggestive of a long-standing vascular occlusion

Discussion

CRAO is an ocular emergency that typically presents with sudden painless loss of vision. The incidence of CRAO is approximately 5/100,000 in individuals above 50 years of age.[1] Carotid artery embolism is the most common cause for CRAO. The common sources for embolism are atherosclerotic plaques and cardiac disorders. The risk of combined occlusion of the central retinal artery and vein is more in individuals with cardiovascular disease or hypercoagulable state. Vascular occlusion secondary to retrobulbar injection is rare and has not been reported commonly in literature. Retrobulbar injection has been widely practiced as a technique of ocular anesthesia for many decades. The technique requires blind insertion of a thin, long needle into the retrobulbar space which contains neural and vascular structures in close association. The anesthetic agent (3 ml of 2% lignocaine with adrenaline 1:200,000 dilution) is typically given using a 26-gauge, 35 mm retrobulbar needle piercing the lower lid at the junction of medial two-third and lateral one-third of the inferior orbital margin. The needle is then directed upward and medially to reach the retrobulbar space. The location of the artery on the inferior surface of the dural sheath before piercing into the substance of optic nerve places the vessel in a vulnerable situation for direct trauma.[2] The risk of arterial injury can be minimized using a 35 mm retrobulbar needle rather than a conventional 38 mm needle and also by rotating the globe downward and outward so as to keep the optic nerve away from the tip of the needle. The piston is withdrawn slightly before injection to assess the position of the needle tip.

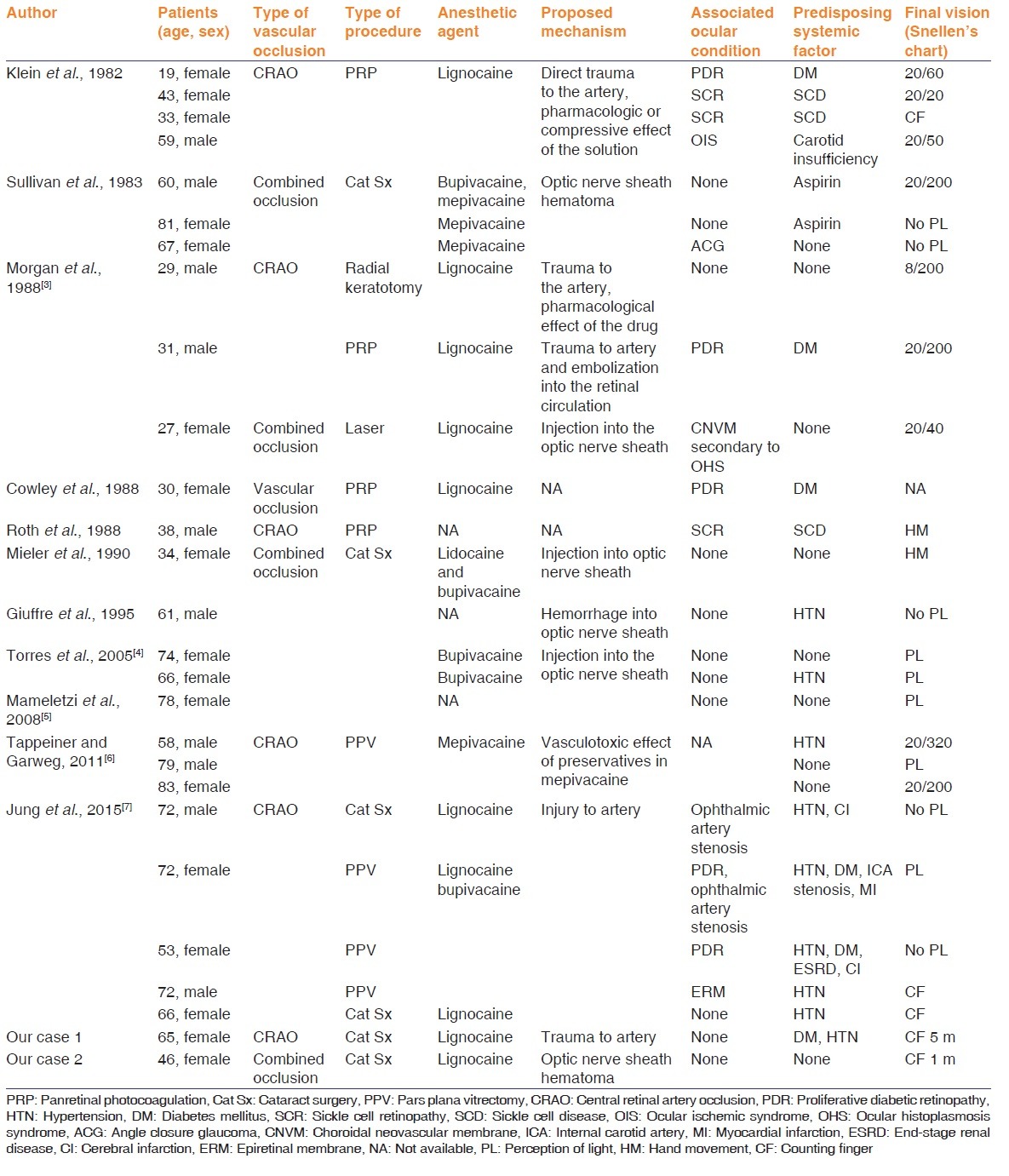

Table 1 summarizes the risk factors, proposed mechanism, and final visual outcome of similar cases that were reported in literature. Klein et al. reported direct trauma to the artery as the mechanism for CRAO. Sullivan et al. reported optic nerve sheath hematoma as the mechanism for combined occlusion. Morgan et al. proposed trauma to the artery and embolization as mechanisms for CRAO and injection into the optic nerve sheath as the mechanism for combined occlusion.[3] Kraushar et al. reported significant retrobulbar hemorrhage associated with marked rise of orbital or IOP as the mechanism for CRAO. Direct trauma to the vessel could have been the most likely mechanism in our first case and optic nerve dural sheath hematoma compressing both artery and the vein as the probable mechanism in our second case. We also report the role of SD OCT in confirming the diagnosis and also to prognosticate the disease condition.[7]

Table 1.

Review of literature - vascular occlusion secondary to retrobulbar injection

Conclusion

We conclude that retrobulbar injections can rarely be associated with dreadful vision-threatening complications such as CRAO and combined vascular occlusion. This can be avoided by having a sound knowledge on the anatomy of retrobulbar structures and by knowing the nuances of retrobulbar injection.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Park SJ, Choi NK, Seo KH, Park KH, Woo SJ. Nationwide incidence of clinically diagnosed central retinal artery occlusion in Korea, 2008 to 2011. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:1933–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katsev DA, Drews RC, Rose BT. An anatomic study of retrobulbar needle path length. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:1221–4. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32748-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgan CM, Schatz H, Vine AK, Cantrill HL, Davidorf FH, Gitter KA, et al. Ocular complications associated with retrobulbar injections. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:660–5. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torres RJ, Luchini A, Weis W, Frecceiro PR, Casella M. Combined central retinal vein and artery occlusion after retrobulbar anesthesia – report of two cases. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2005;68:257–61. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27492005000200020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mameletzi E, Pournaras JA, Ambresin A, Nguyen C. Retinal embolisation with localised retinal detachment following retrobulbar anaesthesia. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2008;225:476–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1027268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tappeiner C, Garweg JG. Retinal vascular occlusion after vitrectomy with retrobulbar anesthesia-observational case series and survey of literature. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249:1831–5. doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1783-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung EH, Park KH, Woo SJ. Iatrogenic central retinal artery occlusion following retrobulbar anesthesia for intraocular surgery. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2015;29:233–40. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2015.29.4.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]