Abstract

A [4 + 3] synthesis of D-manno-heptulose is described. The cascade aldol/hemiketalization reaction of a C4 aldehyde with a C3 ketone provides the differentially protected ketoheptose building block, which can be further reacted to furnish target D-manno-heptulose.

Keywords: aldol reaction, cascade reaction, D-manno-heptulose, higher-carbon sugar, ketoheptose

Introduction

D-manno-Heptulose is a rare naturally occurring seven-carbon sugar first isolated from avocado [1], which exhibited promising diabetogenic effects through suppression of the glucose metabolism and insulin secretion via competitive inhibition of the glucokinase pathway [2–6]. Accordingly, ketoheptoses and fluorinated ketoheptoses were considered to be potential therapeutic agents for hypoglycemia and cancer as well as diagnostic tools for diabetes [7–12]. Amino- and azido-group-containing ketoheptoses were also synthesized for the development of novel antibiotics and the evaluation of carbohydrate–lectin interactions by conjugation with fluorescent quantum dots via click chemistry [13–14]. Besides, differentially protected D-manno-heptulose building blocks could serve as valuable precursors for the synthesis of C-glycosides [15–16].

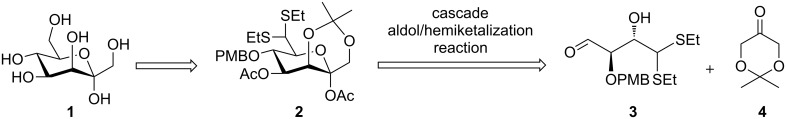

The known synthesis of D-manno-heptulose mainly rely on the use of rearrangements and chain elongation reactions [17]. Rearrangement reactions such as the Lobry de Bruyn rearrangement and the Bilik rearrangement employ unprotected aldoses as substrates, usually yielding an equilibrium mixture of aldoses and ketoses [18–19]. In addition to chain elongations of aldoses employing the Henry reaction, the aldol reaction, and the Wittig reaction for the preparation of ketoheptoses [20–22], sugar lactones were also often utilized for the synthesis of D-manno-heptulose via reactions with C-nucleophiles or conversion into exocyclic glycals followed by dihydroxylation [10–13,23–27]. Remarkably, Thiem et al. reported the highly efficient synthesis of D-manno-heptulose from D-mannose in 59% overall yield over five steps [26]. However, the synthesis of D-manno-heptulose and its derivatives from the common differentially protected ketoheptose building block is still attractive due to the versatile functionalization possibilities of the building block into various derivatives of D-manno-heptulose. A de novo synthesis has proved to be an attractive strategy to produce orthogonally protected carbohydrate building blocks from simple precursors [28–39]. Here, we report a [4 + 3] approach to access differentially protected ketoheptose building blocks, which enables the synthesis of D-manno-heptulose. As depicted in Scheme 1, D-manno-heptulose (1) could be obtained by global deprotection of the differentially protected ketoheptose building block 2. The ketoheptose 2 can be further divided into C4 aldehyde 3 and C3 ketone 4 via a cascade aldol/hemiketalization pathway.

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic analysis of D-manno-heptulose.

Results and Discussion

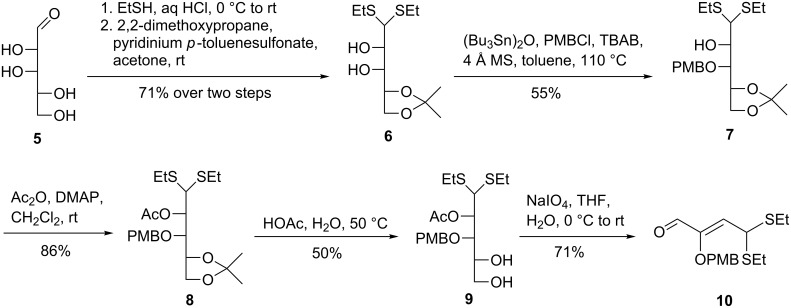

The synthesis of the C4 aldehyde commenced with commercially available D-lyxose (5, Scheme 2). The reaction of 5 with ethanethiol in the presence of hydrochloric acid followed by selective protection of the 4,5-diol with 2,2-dimethoxypropane using pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate as the promoter gave the 4,5-O-isopropylidene derivative 6 in 71% yield over two steps [40]. Treatment of diol 6 with bis(tributyltin) oxide and subsequent exposure to p-methoxybenzyl (PMB) chloride in the presence of tetra-n-butylammonium bromide (TBAB) at 110 °C led to regioselective protection of the 3-OH with the PMB group, affording the 3-O-PMB protected alcohol 7 (55%) [41]. At this stage, we initially planned to synthesize the 2-OH-protected C4 aldehyde for the assembly of the seven-carbon skeleton. Thus, acetylation of the 2-OH group in 7 with acetic anhydride and DMAP in dichloromethane provided ester 8 in 86% yield. The positions of the 2-acetyl and 3-PMB groups were determined by 1H, 13C and 2D NMR spectra of 8 (see Supporting Information File 1 for details). Cleavage of the isopropylidene acetal group in 8 under acidic conditions gave diol 9 (50%). However, oxidative cleavage of diol 9 with sodium periodate resulted in the unexpected formation of α,β-unsaturated aldehyde 10 in 71% yield, indicating that the 2-acetyl group might be prone to initiate the elimination reaction. The double bond of 10 was assigned to have Z-configuration based on the analysis of the NOEs between the olefinic hydrogen and the aldehyde hydrogen (see Supporting Information File 1 for details). In addition, when alcohol 7 was subjected to benzoyl chloride and DMAP in dichloromethane at room temperature or tert-butyldimethylsilyl chloride and imidazole in DMF at room temperature, no reaction occurred probably because of the steric hindrance between the 2-OH group and the surrounding functional groups.

Scheme 2.

Initial attempt on the synthesis of the C4 aldehyde from D-lyxose (5).

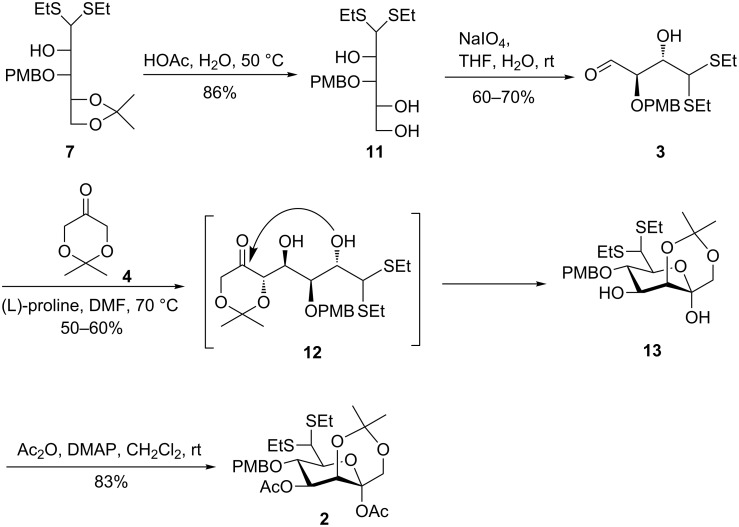

To overcome the difficulties in the synthesis of the 2-OH-protected C4 aldehyde and to improve the synthetic efficiency in the assembly of ketoheptose skeletons, we envisioned ketoheptoses could be assembled by a cascade aldol/hemiketalization reaction between 2-OH-unprotected C4 aldehyde 3 and C3 ketone 4. As such, the isopropylidene acetal group in 7 was cleaved under acidic conditions to produce triol 11 in 86% yield (Scheme 3). Cleavage of the resulting vicinal diol in 11 with sodium periodate led to the C4 aldehyde 3 in nearly 60–70% yield. In this oxidative cleavage reaction, almost no elimination product was found based on TLC monitoring. Given that the C4 aldehyde 3 was unstable upon purification by silica gel column chromatography, it was immediately used for the subsequent coupling after the extraction procedure. The aldol reaction of aldehyde 3 with the readily available ketone 4 [42–43] under the catalysis of L-proline at room temperature for three days proceeded sluggishly, leading to the desired product in a very low yield. Gratifyingly, when the L-proline-catalyzed aldol reaction was performed at 70 °C for one day, the TLC indicated the complete consumption of aldehyde 3, and the generated 4,5-anti-selective coupling intermediate 12 underwent in situ cyclization to provide hemiketal 13 as the major product in about 50–60% yield (35% overall yield from compound 11). Notably, trace amounts of a stereoisomer and a minor highly polar unknown byproduct were also observed in this cascade reaction. The excellent anti-selectivity for the L-proline-catalyzed aldol reaction can be explained by the Houk–List transition state model [43–45]. Compound 13 was then acetylated to afford differentially protected ketoheptose building block 2 in 83% yield. The structure of 2 was unambiguously confirmed by 1H, 13C, and 2D NMR spectra (see Supporting Information File 1 for details). The anomeric α-configuration of compound 2 was confirmed by analysis of the NOE effects between the C-1 hydrogen and the C-5 hydrogen.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of differentially protected ketoheptose building block 2.

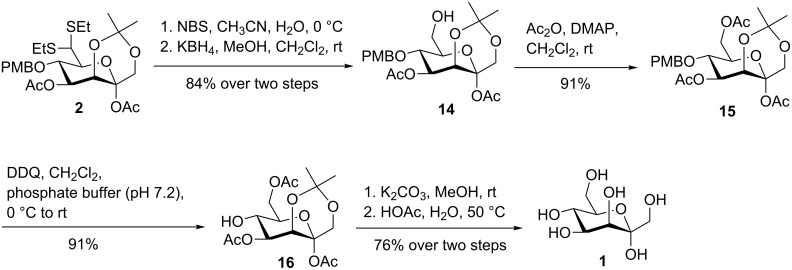

With the ketoheptose building block 2 in hand, we turned our attention to the synthesis of D-manno-heptulose (1). Upon exposure to NBS in acetonitrile and water, the dithioacetal in 2 was cleaved to give the corresponding aldehyde [46–47], which was then reduced by potassium borohydride in a methanol and dichloromethane solvent mixture to produce alcohol 14 as the predominant product (84% over two steps, Scheme 4). In addition, a trace amount of the deacetylated product was also detected . DDQ-mediated oxidative cleavage of the PMB group in alcohol 14 produced only a moderate yield (≈50%) of the 5,7-diol probably due to the presence of the free 7-hydroxy group. We envisaged that protection of the free 7-hydroxy group in 14 followed by treatment with DDQ could yield the desired 5-hydroxy product in high yield. Indeed, acetylation of alcohol 14 with acetic anhydride delivered ester 15 in 91% yield. Removal of the PMB group in 15 with DDQ resulted in a very clean reaction, affording alcohol 16 in an excellent yield (91%). Saponification of all esters in 16 with potassium carbonate followed by acidic cleavage of the isopropylidene acetal group with aqueous acetic acid furnished D-manno-heptulose (1, 76% over two steps). The structure of 1 was found to be in good agreement with those reported for α-D-manno-heptulose (1) by comparison of the NMR spectra (see Supporting Information File 1 for details) [26].

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of D-manno-heptulose (1).

Conclusion

In summary, we have described a [4 + 3] approach for the synthesis of D-manno-heptulose (1) starting from D-lyxose (5). The key step is a cascade aldol/hemiketalization reaction for the construction of the differentially protected ketoheptose building block, which was finally converted into D-manno-heptulose for subsequent biological evaluation. Although the synthesis of D-manno-heptulose (5% overall yield, 13 steps) is not so efficient as the Thiem’s method (59% overall yield, 5 steps), the reported differentially protected ketoheptose building blocks may find further application in the preparation of structurally diverse D-manno-heptulose derivatives.

Supporting Information

Experimental details, characterization data, and NMR spectra of all new compounds.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the National Thousand Young Talents Program (YC0130518, YC0140103), the Shanghai Pujiang Program (15PJ1401500), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (WY1514052), and the Opening Project of State Key Laboratory of Bio-organic and Natural Products Chemistry (Y100-D-1501) is gratefully acknowledged.

This article is part of the Thematic Series "Biomolecular systems".

References

- 1.La Forge F B. J Biol Chem. 1917;28:511–522. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roe J H, Hudson C S. J Biol Chem. 1936;112:443–449. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon E, Kraicer P F. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1957;69:592–601. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(57)90523-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paulsen E P, Richenderfer L, Winick P. Nature. 1967;214:276–277. doi: 10.1038/214276b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coore H G, Randle P J. Biochem J. 1964;91:56–59. doi: 10.1042/bj0910056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zelent D, Najafi H, Odili S, Buettger C, Weik-Collins H, Li C, Doliba N, Grimsby J, Matschinsky F M. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:306–310. doi: 10.1042/BST0330306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paulsen E P. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1968;150:455–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1968.tb19069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Board M, Colquhoun A, Newsholme E A. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3278–3285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malaisse W J. Diabetologia. 2001;44:393–406. doi: 10.1007/s001250051635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leshch Y, Waschke D, Thimm J, Thiem J. Synthesis. 2011:3871–3877. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1289598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waschke D, Leshch Y, Thimm J, Himmelreich U, Thiem J. Eur J Org Chem. 2012:948–959. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201101238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malaisse W J, Zhang Y, Louchami K, Sharma S, Dresselaers T, Himmelreich U, Novotny G W, Mandrup-Poulsen T, Waschke D, Leshch Y, et al. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;517:138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leshch Y, Jacobsen A, Thimm A, Thiem J. Org Lett. 2013;15:4948–4951. doi: 10.1021/ol4021699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidtke C, Kreuziger A-M, Alpers D, Jacobsen A, Leshch Y, Eggers R, Kloust H, Tran H, Ostermann J, Schotten T, et al. Langmuir. 2013;29:12593–12600. doi: 10.1021/la402826f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy D E, Tang C. The chemistry of C-glycosides. Oxford: Pergamon; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du Y, Linhardt R J, Vlahov I R. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:9913–9959. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(98)00405-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobsen A, Thiem J. Curr Org Chem. 2014;18:2833–2841. doi: 10.2174/1385272819666141016215205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montgomery E M, Hudson C S. J Am Chem Soc. 1939;61:1654–1658. doi: 10.1021/ja01876a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hricoviniova Z, Hricovini M, Petrusoa M, Matulova M, Petrus L. Chem Pap. 1998;52:238–243. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sowden J C. J Am Chem Soc. 1950;72:3325. doi: 10.1021/ja01163a558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaffner R, Isbell H S. J Org Chem. 1962;27:3268–3270. doi: 10.1021/jo01056a069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng J, Fang Z, Li S, Zheng B, Jiang Y. Carbohydr Res. 2009;344:2093–2095. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kampf A, Dimant E. Carbohydr Res. 1974;32:380–382. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)82116-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bessières B, Morin C. J Org Chem. 2003;68:4100–4103. doi: 10.1021/jo0342166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu X, Yin Q, Yin J, Chen G, Wang X, You Q-D, Chen Y-L, Xiong B, Shen J. Eur J Org Chem. 2014:6150–6154. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201402757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waschke D, Thimm J, Thiem J. Org Lett. 2011;13:3628–3631. doi: 10.1021/ol2012764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li X, Takahashi H, Ohtake H, Shiro M, Ikegami S. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:8053–8066. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)00775-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Northrup A B, MacMillan D W C. Science. 2004;305:1752–1755. doi: 10.1126/science.1101710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Timmer M S M, Adibekian A, Seeberger P H. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:7605–7607. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed M M, Berry B P, Hunter T J, Tomcik D J, O’Doherty G A. Org Lett. 2005;7:745–748. doi: 10.1021/ol050044i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adibekian A, Timmer M S M, Stallforth P, van Rijn J, Werz D B, Seeberger P H. Chem Commun. 2008:3549–3551. doi: 10.1039/B805159C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stallforth P, Adibekian A, Seeberger P H. Org Lett. 2008;10:1573–1576. doi: 10.1021/ol800227b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shan M, Xing Y, O’Doherty G A. J Org Chem. 2009;74:5961–5966. doi: 10.1021/jo9009722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohara T, Adibekian A, Esposito D, Stallforth P, Seeberger P H. Chem Commun. 2010;46:4106–4108. doi: 10.1039/c000784f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calin O, Pragani R, Seeberger P H. J Org Chem. 2012;77:870–877. doi: 10.1021/jo201883k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Babu R S, Chen Q, Kang S-W, Zhou M, O’Doherty G A. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:11952–11955. doi: 10.1021/ja305321e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gati W, Rammah M M, Rammah M B, Couty F, Evano G. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:9078–9081. doi: 10.1021/ja303002a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mlynarski J, Gut B. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:587–596. doi: 10.1039/C1CS15144D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang H-Y, Yang K, Yin D, Liu C, Glazier D A, Tang W. Org Lett. 2015;17:5272–5275. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Delft F L, Rob A, Valentijn P M, van der Marel G A, van Boom J H. J Carbohydr Chem. 1999;18:165–190. doi: 10.1080/07328309908543989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grindley T B. Adv Carbohydr Chem Biochem. 1998;53:17–142. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2318(08)60043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suri J T, Mitsumori S, Albertshofer K, Tanaka F, Barbas C F., III J Org Chem. 2006;71:3822–3828. doi: 10.1021/jo0602017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grondal C, Enders D. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:329–337. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2005.09.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bahmanyar S, Houk K N, Martin H J, List B. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:2475–2479. doi: 10.1021/ja028812d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoang L, Bahmanyar S, Houk K N, List B. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:16–17. doi: 10.1021/ja028634o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corey E J, Erickson B W. J Org Chem. 1971;36:3553–3560. doi: 10.1021/jo00822a019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crich D, de la Mora M A, Cruz R. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:35–44. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)01087-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental details, characterization data, and NMR spectra of all new compounds.