Abstract

Objective

Suprastomal granulomas pose a persistent challenge for tracheostomy-dependent children. They can limit phonation, cause difficulty with tracheostomy tube changes and prevent decannulation. We describe the use of the coblator for radiofrequency plasma ablation of suprastomal granulomas in five consecutive children from September 2012 to January 2016.

Method

Retrospective case series at a tertiary medical center

Results

The suprastomal granuloma could be removed with the coblator in all 5 cases. Three were removed entirely endoscopically and 2 required additional external approach through the tracheal stoma for complete removal. There were no intraoperative or postoperative complications. One patient was subsequently decannulated and 2 patients have improved tolerance of their speaking valves. Two patients remain ventilator dependent, but their bleeding and difficulty with tracheostomy tube changes resolved. Three of the patients have had subsequent re-evaluation with bronchoscopy, demonstrating resolution or markedly decreased size of the granuloma. This technique is time efficient, simple and minimizes risks associated with other techniques. The relatively low temperature and use of continuous saline irrigation with the coblator device minimizes the risk of airway fires. Additionally, the risk of hypoxia from keeping a low fractional inspiratory oxygen level (FIO2) to prevent fire is avoided. The concurrent suction in the device decreases blood and tissue displacement into the distal airway.

Conclusion

Coblation can be used safely and effectively with an endoscopic or external approach to remove suprastomal granulomas in tracheostomy-dependent children. More studies that are larger and have longer follow-up are needed to evaluate the use of this technique.

Keywords: pediatric suprastomal granuloma, coblation, radiofrequency plasma ablation, tracheostomy

1. Introduction

Suprastomal granulomas present a common challenge in the management of tracheostomy dependent children. Rosenfeld et al reviewed 265 rigid bronchoscopies in 50 children with tracheostomy-dependent subglottic stenosis and found that granulomas had developed in 80% of the patients [1]. The granuloma formation was not found to be related to any known patient factor including age or duration of tracheostomy. They found no significant reduction in recurrence after excision and therefore did not recommend removal in otherwise stable patients. Mahadevan et al found that granuloma formation occurred in most pediatric patients with tracheostomy and more than 12% required intervention [2]. In a review of 282 cases over 37 years Ozmen et al found that the majority of tracheotomies in children were performed for upper airway obstruction and decannulation was achieved in 35% of cases [3]. Suprastomal granuloma formation is likely due to stasis of secretions, chronic infection, friction or foreign body reaction at the tracheostomy site. Obstructive suprastomal granulomas can prevent planned decannulation and cause significant respiratory distress in the event of an accidental decannulation. For patients with a long-term tracheostomy requirement, a granuloma can also limit or preclude speaking valve use and make tracheostomy tube changes difficult.

Coblation (abbreviation for controlled ablation) is one of the several available techniques to remove suprastomal granulomas. It utilizes bipolar radiofrequency plasma ablation to remove excess tissue. Since its introduction at the beginning of the 21st century it has been used frequently for adenotonsillectomy [4] and inferior turbinate reduction [5]. Its use has also been described for microcystic lymphatic malformations [6], aerodigestive tumors [7], airway stenosis [8] and laryngeal papillomatosis [9]. In 2009 Kitsko et al initially described a technique of using coblation to remove suprastomal granulomas externally through the tracheal stoma under bronchoscopic guidance [10]. We present five cases of suprastomal granuloma that were effectively managed with a similar, but primarily endoscopic coblation technique.

2. Materials and methods

Duke University Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to review of these patients (Pro00068727).

2.1 Surgical Technique

General anesthesia is induced. The tracheostomy tube is replaced by a standard cuffed endotracheal tube inserted into the tracheal stoma for greater ease in ventilation and repositioning of the tube. Next, direct laryngoscopy is performed with a Parsons laryngoscope and the patient is placed in suspension. Bronchoscopy is performed with a zero-degree telescope. Then, the Smith and Nephew® Procise MLW or LW Coblation wand is passed endoscopically through the larynx and into the suprastomal area to ablate the granuloma under direct telescopic visualization. This completely endoscopic approach differs from the external technique that has been previously described by Kitsko et al [10]. An ablation setting of 7 and coagulation setting of 4 is used with the Smith and Nephew® Coblator II Surgery System. The end of the wand can be slightly bent as needed to allow for the correct angle of contact between the distal end of the instrument and the granuloma.

If the granuloma cannot be completely ablated endoscopically, then the endotracheal tube is temporarily removed and the same wand used externally through the tracheal stoma to ablate the remainder of the granuloma under continued endoscopic visualization. The instrument can also be used as a manipulation probe, because of the continuous suction through the device even without activation of the ablation function. This feature facilitates complete and rapid removal of the granuloma. If hemostasis is not achieved through the ablation function, then the coagulation setting can be used. A tracheostomy tube is replaced at the end of the procedure.

3. Results

This technique was used effectively in all 5 cases that the senior author E.R. has attempted with this technique. Three of the 5 patients had recurrent granulomas after removal with another technique, but they were subsequently successfully removed with the coblator. Two patients remained ventilator dependent, but their bleeding and difficulty with tracheostomy tube changes resolved. Two patients had improved tolerance of their speaking valves. One patient was successfully decannulated. Three of the patients have had subsequent re-evaluation with bronchoscopy demonstrating resolution or substantially decreased size of the granuloma. There were no immediate or delayed complications from this procedure and the patients have done well in subsequent follow-up ranging from 6 months to 3 years.

3.1. Patient 1

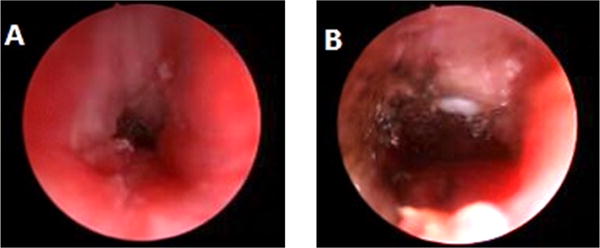

A 6 month old with Costello syndrome underwent tracheostomy for chronic respiratory failure. She was subsequently unable to tolerate a speaking valve. At 18 months a granuloma was removed with the microdebrider and cup forceps. Two years later, a recurrent granuloma was removed with the CO2 laser with only slight improvement in speaking valve tolerance. One year later a completely obstructing granuloma was identified (Fig. 1A) and removed with the coblator (Fig. 1B). At one year follow up, she was tolerating her speaking valve and surveillance bronchoscopy showed no granuloma (Fig. 1C).

Fig 1.

A. Partially obstructing suprastomal granuloma. B. Immediately after coblation of granuloma. C. Bronchoscopy one year after coblation of granuloma.

3.2. Patient 2

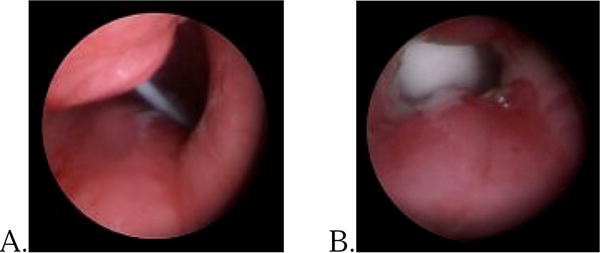

A 3 month old with Pierre Robin sequence and a history of prolonged intubation underwent emergent tracheostomy after acute decompensation in the setting of subglottic stenosis. Two bronchoscopies performed during the next year showed subglottic stenosis, requiring balloon dilation, however no suprastomal granuloma was noted. After endoscopic dilation of the stenosis at 18 months of age she was tolerating a speaking valve. A surveillance bronchoscopy prior to initiating cap trials at 3 years of age revealed grade 3 subglottic stenosis and an obstructive suprastomal granuloma. These were treated with balloon dilation and cup forceps, respectively. She subsequently developed more difficulty with speaking valve use and bronchoscopy revealed recurrence of the subglottic stenosis and granuloma at 4 years of age (Fig. 2A). These were treated with balloon dilation and coblation, respectively. This granuloma required an endoscopic and external approach through the stoma to achieve a patent subglottic airway (Fig. 2B). Six months later there was a small amount of recurrent granuloma that was removed. Six months later she continued to phonate well and was proceeding towards decannulation.

Fig 2.

A. Grade 3 subglottic stenosis and suprastomal granuloma obscuring view of tracheostomy tube. B. Visible tracheostomy tube after balloon dilation and coblation.

3.3. Patient 3

A 7 month old with Pompe’s disease, upper airway collapse, diaphragm paralysis and BiPap dependence underwent tracheostomy. At 4 years of age her caregivers had difficulty with tracheostomy tube changes due to high resistance and bleeding. Suprastomal granuloma that extended to the superior mucocutaneous junction of the stoma was removed with the coblator. The tracheostomy change problems resolved and her tube could be upsized to accommodate her continued need for ventilator support. Three years after the procedure a bronchoscopy showed only minimal suprastomal granulation.

3.4. Patient 4

A 4 year old with cerebral palsy and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy underwent tracheostomy for ventilator dependence. She presented to the emergency department 2 years later after her dislodged tracheostomy tube could not be replaced at home. A suprastomal granuloma was subsequently identified (Fig. 3A) and removed, which enabled a necessary tube upsize for continued nighttime ventilator support (Fig. 3B). The difficulty with the tube changes resolved over the subsequent 11 months.

Fig. 3.

A. Partially obstructive granuloma. B. After coblation of the granuloma with increased airway patency and larger tracheostomy tube.

3.5. Patient 5

This patient was previously treated at another institution with a history of two supraglottoplasties for laryngomalacia at 4 and 6 weeks of age and tracheostomy at 3 months. Three bronchoscopies were subsequently performed and showed suprastomal granuloma, which was removed with the CO2 laser during the second procedure. On our evaluation at 3 years of age he was tolerating only 3 hours a day of speaking valve. He underwent adenotonsillectomy, direct laryngoscopy, bronchoscopy and removal of the persistent suprastomal granuloma. After removal of the granuloma he demonstrated improved phonation and tolerance of his speaking valve. A fiberoptic laryngoscopy demonstrated minimal recurrent granulation. After capping trials and a capped sleep study he was successfully decannulated 6 months after the granuloma removal. He has done well for 12 months since then.

5. Discussion

While some suprastomal granulomas can be managed conservatively, surgical excision is necessary in the presence of tracheostomy tube obstruction, bleeding, limited phonation or delay in decannulation. Excellent visualization and precise excision of suprastomal granulomas can usually be achieved with an endoscopic approach, making it the preferred approach. Granulomas can be removed using either cold steel (hook eversion, cup forceps, or sphenoid punch), laser (CO2 or KTP), microdebrider and most recently coblation.

Most cold steel endoscopic approaches remove the granuloma through the stoma while under endoscopic guidance. Hook eversion was first described by Reilly et al in 1985 [11]. An assistant holds the bronchoscope while the surgeon everts the granuloma out through the stoma and sharply excises it. In 2011 a survey of pediatric otolaryngologists indicated that the hook-eversion remained a popular technique with over 67% of respondents utilizing it [12]. The optical forceps technique uses cupped forceps passed through the endoscope. This provides direct visualization of the granuloma for removal and does not require an assistant as in the hook eversion technique. However, granulomas can only be removed in a piecemeal fashion, which can result in bleeding. Optical forceps are therefore best suited for smaller, softer granulomas [13]. In the sphenoid punch technique the forceps is inserted into the stoma to grasp and excise the granuloma and can be used for fibrous, firm tissue [14]. One risk inherent to all types of the cold-steel technique is the dislodgement of granuloma into the distal bronchi, which can lead to acute respiratory failure.

Endoscopic laser surgery has been utilized in many aspects of pediatric airway surgery including suprastomal granuloma excision. Carbon dioxide (CO2) laser is utilized most frequently as it has lower penetrating depths and less risk of damage to surrounding healthy tissue [15]. More recently, a fiberoptic carrier has been used to deliver the CO2 laser increasing the ease of use. The KTP (Potassium-Titanium-Phosphate) can also be used in this location [16]. Because of the risk of collateral damage and airway fire ignition, strict laser precautions must be followed including protection of nearby tissues and minimizing the flow of oxygen from the anesthesia circuit. Use of a low FIO2 can lead to hypoxia, especially in those children who have an underlying pulmonary condition, which is common in the tracheostomy dependent pediatric population.

The use of powered debridement for excision of suprastomal granulomas in adults has been extensively described. However, the technique has not been utilized in the pediatric population to the same extent [17]. In one series of 21 pediatric patients, there was no significant difference in duration of procedure and intra-operative bleeding in children undergoing powered debridement versus cold-steel excision [18]. Both techniques can leave bleeding tissue, that can lead to blood accumulation in the distal airways and then an additional instrument may be needed to obtain hemostasis. If electrocautery is used to obtain hemostasis, then just as with the laser, low FIO2 is necessary to prevent fire ignition.

Electrocautery can be used alone to remove the granuloma while concurrently obtaining hemostasis. Low FIO2 is needed and even in the absence of an airway fire, collateral thermal damage and cartilaginous injury can occur. The average temperature reached by electrocautery ranges from 400 to 600° Celsius. Alternatively, the coblator reaches a tenth of the heat in the range of 40 to 70° Celsius. This relatively low temperature limits the risk of airway fires and collateral tissue damage to the sensitive subglottic area. The coblator has been tested at its maximal intensity settings in direct contact with standard endotracheal tubes with high oxygen concentrations, without resulting airway fire [19]. It therefore does not require low FIO2 or a specific endotracheal tube type. We have not experienced any collateral damage to the adjacent tissues or endotracheal tube by the coblator.

Each treatment modality varies in its ease of use, operative time, effectiveness, and potential complications. The main advantages of the coblator technique are rapid removal, ease of using the same instrument both endoscopically and externally, ability to continue oxygenation without a fire risk, reduced thermal damage, integrated suction and coagulation function that minimize distal tissue and blood displacement. Surgeons should use the technique that is safest and most effective in their own hands. Cost effectiveness should always be considered. Although there is additional cost to the coblator instrument, this can be balanced by a faster operative time with lower room and anesthesia costs. Using only one instrument during the procedure to both remove the granuloma and achieve hemostasis can also be time and cost-effective.

6. Conclusion

This case series demonstrates the utility of the coblator for suprastomal granuloma removal in pediatric patients. There were no complications from this safe technique and all patients experienced a clinical improvement during a moderate length of follow-up. Reports of larger studies and longer-term follow-up are needed to further evaluate the continued use of this technique as an alternative to other available options.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by a NIDCD training grant to the Division of Head and Neck Surgery & Communication Sciences at Duke University (T32 DC013018-03).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rosenfeld RM, Stool SE. Should granulomas be excised in children with long-term tracheotomy? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:1323–1327. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1992.01880120049010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahadevan M, Barber C, Salkeld L, Douglas G, Mills N. Pediatric tracheotomy: 17 year review. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2007;71:1829–1835. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozmen S, Ozmen OA, Unal OF. Pediatric tracheotomies: a 37-year experience in 282 children. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2009;73:959–961. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall DJ, Littlefield PD, Birkmire-Peters DP, Holtel MR. Radiofrequency ablation versus electrocautery in tonsillectomy. Otolaryngology–head and neck surgery: official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2004;130:300–305. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang ZY, Pereira KD, Friedman NR, Mitchell RB. Inferior turbinate surgery in children: a survey of practice patterns. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1620–1623. doi: 10.1002/lary.23292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goswamy J, Penney SE, Bruce IA, Rothera MP. Radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of paediatric microcystic lymphatic malformations. J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127:279–284. doi: 10.1017/S0022215113000029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwang SY, Jefferson N, Mohorikar A, Jacobson I. Radiofrequency coblation of congenital nasopharyngeal teratoma: a novel technique. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2015;2015:634958. doi: 10.1155/2015/634958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fastenberg JH, Roy S, Smith LP. Coblation-assisted management of pediatric airway stenosis. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2016;87:213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rachmanidou A, Modayil PC. Coblation resection of paediatric laryngeal papilloma. J Laryngol Otol. 2011;125:873–876. doi: 10.1017/S0022215111001253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitsko DJ, Chi DH. Coblation removal of large suprastomal tracheal granulomas. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:387–389. doi: 10.1002/lary.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reilly JS, Myer CM., 3rd Excision of suprastomal granulation tissue. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:1545–1546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kraft S, Patel S, Sykes K, Nicklaus P, Gratny L, Wei JL. Practice patterns after tracheotomy in infants younger than 2 years. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137:670–674. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2011.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta A, Cotton RT, Rutter MJ. Pediatric suprastomal granuloma: management and treatment. Otolaryngology–head and neck surgery: official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2004;131:21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prescott CA. Peristomal complications of paediatric tracheostomy. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 1992;23:141–149. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(92)90050-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan Y, Olszewski AE, Hoffman MR, Zhuang P, Ford CN, Dailey SH, Jiang JJ. Use of lasers in laryngeal surgery. J Voice. 2010;24:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharp HR, Hartley BE. KTP laser treatment of suprastomal obstruction prior to decannulation in paediatric tracheostomy. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2002;66:125–130. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(02)00217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang TJ, Lee LI, Li HY. Powered instrumentation in the treatment of tracheal granulation tissue for decannulation. Otolaryngology–head and neck surgery: official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2005;133:520–524. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.05.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen C, Bent JP, Parikh SR. Powered debridement of suprastomal granulation tissue to facilitate pediatric tracheotomy decannulation. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2011;75:1558–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matt BH, Cottee LA. Reducing risk of fire in the operating room using COBLATION™ technology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143:454–455. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]