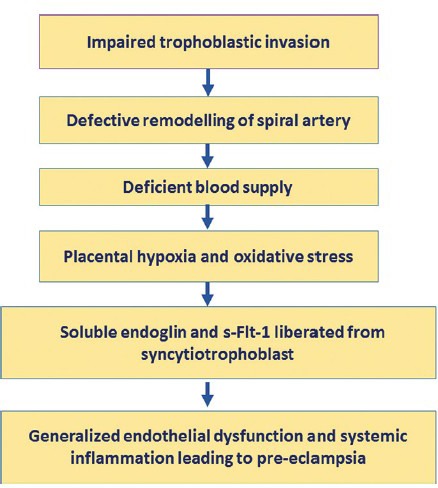

Pre-eclampsia (PE) is defined as the newly developed maternal hypertension (diastolic blood pressure more than 90 mmHg), proteinuria (more than 300 mg in 24 h) and oedema at or after 20 weeks of pregnancy1. It is a relatively common disease (seen in 3% of pregnant women) and is an important cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Till date, the exact aetiology of PE is unknown; however, the predominant hypothesis is the disturbed placentation in the early part of pregnancy due to impaired trophoblastic invasion and defective remodelling of spiral artery in PE2. This may cause ischaemia in the placental bed and release of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase and other mediators. These mediators subsequently lead to generalized endothelial dysfunction and systemic inflammation3 (Fig. 1). Three types of cells play a vital role in optimal placentation (proper trophoblastic invasion and spiral artery remodelling): decidual natural killer (DNK) cells, extravillous trophoblast (EVT) and macrophages (Table).

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram showing the possible aetiopathogenesis of pre-eclampsia. sFlt-1, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase.

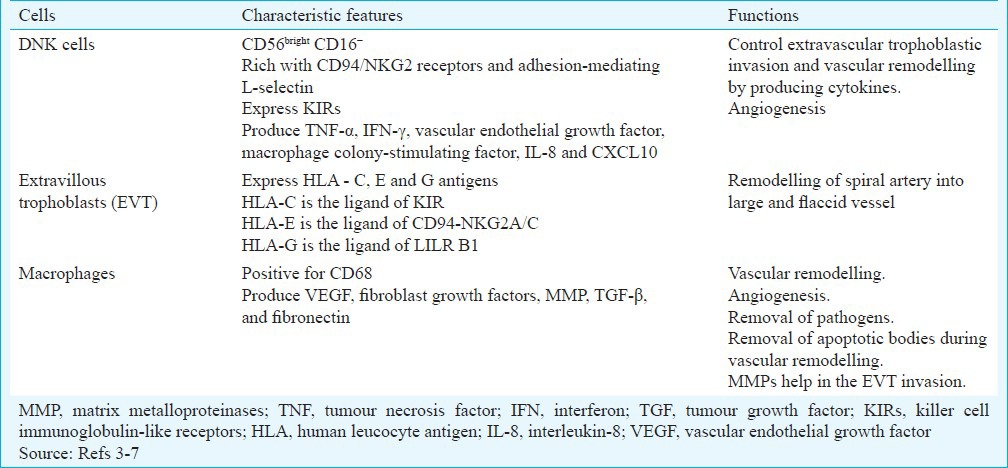

Table.

Characteristic features and functions of decidual natural killer (DNK) cells, extravascular trophoblasts and macrophages in the placental bed

DNK cells: These cells are major constituents of leucocytes (75%) in the decidua. These are accumulated in the placenta probably by chemoattractants or are differentiated in situ from the stromal cells. DNK cells are more concentrated around the spiral arteries, and these are in close proximity with EVT. The DNK cells are phenotypically different from the peripheral natural killer cells. The DNK cells are phenotypically CD56bright CD16−. These are rich with CD94/NKG2 receptors and adhesion-mediating L-selectin4. DNK cells also express killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) and produce important cytokines and angiogenic factors such as tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interferon gamma (IFN-γ), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interleukin-8 (IL-8) and chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 (CXCL10)5,6,7. These factors are essential for extravillous trophoblastic invasion, angiogenesis, spiral artery remodelling and successful placentation.

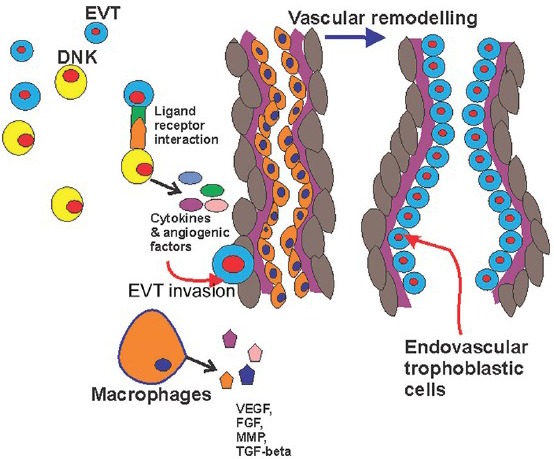

Extravillous trophoblast (EVT): Extravillous trophoblast comprised syncytio and cytotrophoblastic cells that are present outside the villi. In the early part of pregnancy (before week 20), EVT invades in the functional endometrium of the mother. It plays an important role in remodelling of the spiral artery. The smooth muscle of the vessel wall is discretely lost, and the endothelial cells of the vessels are completely replaced by EVT. The spiral artery becomes large and flaccid and provides increased blood in the intervillous space to the growing foetus (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram showing the interaction of extravascular trophoblast, decidual natural killer cells and macrophages along with vascular remodelling. EVT, extravascular trophoblast; DNK cell, decidual natural killer cell; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase, TGF, tumour growth factor.

Interaction of EVT and DNK cells: There is growing evidence that DNK cells regulate the invasion of EVT and thereby remodelling of spiral artery7. The receptors of DNK cells combine with the ligands of the EVT cells resulting in the release of cytokines: IL-8 and interferon-inducible protein-10 chemokines7. These cytokines are helpful in trophoblastic invasion and angiogenesis. DNK cells also liberate various matrix metalloproteinases (MMP2 and MMP9), urokinase plasminogen activator, etc., that help in the breakdown of extracellular matrix for the successful invasion of EVT8. EVT expresses human leucocyte antigen (HLA) – C, E and G antigens which bind with the corresponding receptors on the DNK cells such as KIR, CD 94-NKG2A/C and LILR B1 ligand, respectively9,10. Hiby et al11 have shown that the mother lacking activating KIR (AA genotype) and foetus containing HLA C2 generate a strong inhibitory response on DNK cells leading to impaired remodelling of the uterine spiral arteries due to lack of adequate cytokines from the DNK cells. They noted that this group of patients were prone to develop PE.

Macrophages: Macrophages in the placental bed are responsible for vascular remodelling and angiogenesis by producing VEGF, fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), tumour growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and fibronectin12. These also help in the removal of the apoptotic bodies during invasion of EVT and remodelling of spiral arteries13. Macrophages are infiltrated in the placenta by the chemoattractant CCL2, CCL7, CCL4, etc., produced by decidual cells and trophoblasts14. Compared with normal pregnancy increased macrophage infiltration is noted in PE15.

There are conflicting studies regarding the number of DNK cells and macrophages in PE. Increased16, decreased17 and no alteration of the number of DNK cells in the decidua in PE patients have been reported18. Milosevic-Stevanovic et al19 in this issue analysed the number of DNK cells and macrophages in PE and normal pregnant women. They did CD56 and CD68 immunostaining for DNK cells and macrophages, respectively, on the curettings from the placental bed at the time of caesarean section. They noted significantly lower number of macrophages in the cases of PE than normal control. The number of CD56 positive DNK cells was less in PE patients than control; however, this was not significant. They also noted significantly greater number of DNK cells in PE with intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) compared to PE without IUGR. The variation in the demonstration of the number of DNK cells in this study from the others may be due to the difference in sampling (curettings from the placental bed versus attached decidua with placenta) and measurement technique (immunocytochemistry versus flow cytometry)20. The gestational age of the PE patients and the control group was not matched in this study. Moreover, the pathogenesis of PE begins in early weeks of pregnancy followed by the late appearance of the disease. Therefore, it is possible that the all the alterations in the number of the DNK cells and macrophages may be the effect of PE but not the cause.

The mere increase or decrease in DNK cells may not have much role in the pathogenesis of PE. Hiby et al11 have described that the functional activity of the DNK cells is very important which depends mainly on the fine balance between activating or inhibiting receptors of KIR of DNK cells with corresponding ligands of HLA of EVT. The pathogenesis of the PE is possibly multifactorial including DNK cell receptors, HLA typing of the mother and the cytokine profiles of the local placental area. At present, more data are needed to understand the pathogenesis of PE and preventing this menace of pregnancy.

References

- 1.Milne F, Redman C, Walker J, Baker P, Bradley J, Cooper C, et al. The pre-eclampsia community guideline (PRECOG): how to screen for and detect onset of pre-eclampsia in the community. BMJ. 2005;330:576–80. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7491.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brosens I, Robertson WB, Dixon HG. Wynn RM. Obstetrics and gynecology annual. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1972. The role of spiral arteries in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia; pp. 177–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steegers EA, von Dadelszen P, Duvekot JJ, Pijnenborg R. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2010;376:631–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryceson YT, Chiang SC, Darmanin S, Fauriat C, Schlums H, Theorell J, et al. Molecular mechanisms of natural killer cell activation. J Innate Immun. 2011;3:216–26. doi: 10.1159/000325265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li XF, Charnock-Jones DS, Zhang E, Hiby S, Malik S, Day K, et al. Angiogenic growth factor messenger ribonucleic acids in uterine natural killer cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1823–34. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.4.7418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Oliveira LG, Lash GE, Murray-Dunning C, Bulmer JN, Innes BA, Searle RF, et al. Role of interleukin 8 in uterine natural killer cell regulation of extravillous trophoblast cell invasion. Placenta. 2010;31:595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanna J, Goldman-Wohl D, Hamani Y, Avraham I, Greenfield C, Natanson-Yaron S, et al. Decidual NK cells regulate key developmental processes at the human fetal-maternal interface. Nat Med. 2006;12:1065–74. doi: 10.1038/nm1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naruse K, Lash GE, Innes BA, Otun HA, Searle RF, Robson SC, et al. Localization of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, MMP-9 and tissue inhibitors for MMPs (TIMPs) in uterine natural killer cells in early human pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:553–61. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King A, Allan DS, Bowen M, Powis SJ, Joseph S, Verma S, et al. HLA-E is expressed on trophoblast and interacts with CD94/NKG2 receptors on decidual NK cells. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1623–31. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200006)30:6<1623::AID-IMMU1623>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vilches C, Parham P. KIR: Diverse, rapidly evolving receptors of innate and adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:217–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.092501.134942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiby SE, Walker JJ, O’shaughnessy KM, Redman CW, Carrington M, Trowsdale J, et al. Combinations of maternal KIR and fetal HLA-C genes influence the risk of preeclampsia and reproductive success. J Exp Med. 2004;200:957–65. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sunderkötter C, Steinbrink K, Goebeler M, Bhardwaj R, Sorg C. Macrophages and angiogenesis. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;55:410–22. doi: 10.1002/jlb.55.3.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abrahams VM, Kim YM, Straszewski SL, Romero R, Mor G. Macrophages and apoptotic cell clearance during pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2004;51:275–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2004.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li M, Wu ZM, Yang H, Huang SJ. NFκB and JNK/MAPK activation mediates the production of major macrophage- or dendritic cell-recruiting chemokine in human first trimester decidual cells in response to proinflammatory stimuli. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:2502–11. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang SJ, Chen CP, Schatz F, Rahman M, Abrahams VM, Lockwood CJ. Pre-eclampsia is associated with dendritic cell recruitment into the uterine decidua. J Pathol. 2008;214:328–36. doi: 10.1002/path.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stallmach T, Hebisch G, Orban P, Lü X. Aberrant positioning of trophoblast and lymphocytes in the feto-maternal interface with pre-eclampsia. Virchows Arch. 1999;434:207–11. doi: 10.1007/s004280050329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eide IP, Rolfseng T, Isaksen CV, Mecsei R, Roald B, Lydersen S, et al. Serious foetal growth restriction is associated with reduced proportions of natural killer cells in decidua basalis. Virchows Arch. 2006;448:269–76. doi: 10.1007/s00428-005-0107-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sánchez-Rodríguez EN, Nava-Salazar S, Mendoza-Rodríguez CA, Moran C, Romero-Arauz JF, Ortega E, et al. Persistence of decidual NK cells and KIR genotypes in healthy pregnant and preeclamptic women: a case-control study in the third trimester of gestation. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2011;9:8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milosevic-Stevanovic J, Krstic M, Radovic-Janosevic D, Popovic J, Tasic M, Stojnev S. Number of decidual natural killer cells & macrophages in pre-eclampsia. Indian J Med Res. 2016;144:823–30. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_776_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams PJ, Bulmer JN, Searle RF, Innes BA, Robson SC. Altered decidual leucocyte populations in the placental bed in pre-eclampsia and foetal growth restriction: a comparison with late normal pregnancy. Reproduction. 2009;138:177–84. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]