Synthesis of the triflyloxyphosphonium dication is presented bearing two electrophilic sites which are selectively addressable by different nucleophiles.

Synthesis of the triflyloxyphosphonium dication is presented bearing two electrophilic sites which are selectively addressable by different nucleophiles.

Abstract

A carbodiphosphorane ((Ph3P)2C) mediated synthesis of the first triflyloxyphosphonium dication (12+) bearing two electrophilic sites is presented. Depending on the nucleophile, 12+ reacts selectively either at the sulfur atom of the triflyloxy moiety or at the directly attached phosphorus atom. In substitution reactions at the phosphorus atom the triflyloxy moiety serves as a leaving group and enables the synthesis of rare examples of pseudo-halophosphonium dications.

Carbodiphosphoranes as four electron donors with σ- and π-symmetry are considered as strong donor ligands.1 Their donor abilities were recently used to prepare several main group Lewis acids,2 including the syntheses of phosphenium dications.3 Phosphonium cations are gaining strong reputation as very potent Lewis acids,4 particularly in the field of FLP chemistry,5 as organocatalyst6,7 for molecule transformations8 and as assisting group in boron based molecular receptors for selective anion complexation.9 Electron deficient phosphonium dications of type A bearing at least one electron withdrawing substituent X which can also act as a good leaving group should allow for facile substitution reactions at the phosphonium moiety, thus, should enable the synthesis of a variety of functionalized phosphonium cations (Scheme 1). In this respect, the well-established and conveniently accessible triflyloxy-group (OTf) comprises two important functions – firstly, it has electron withdrawing properties and secondly, the possibility to act as a suitable leaving group via liberation of the weakly coordinating triflate anion in nucleophilic substitution reactions. Thus, triflyloxy-substituted pnictogen derivatives such as Ph3Pn(OTf)2 (Pn = As, Sb, and Bi) were synthesized and used in nucleophilic substitution reactions with a series of Lewis bases.10 The related P-based [Ph3P-OTf][OTf] salt was suggested to form as an intermediate in the reaction of Ph3P(O) with Tf2O to give the well-known Hendrickson reagent [(Ph3P)2O][OTf]2;11 however, to the best of our knowledge, the triflyloxyphosphonium cations of type [R3P-OTf]+ have never been isolated to date.

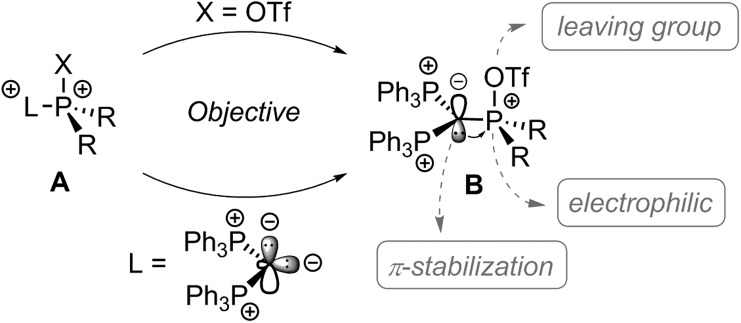

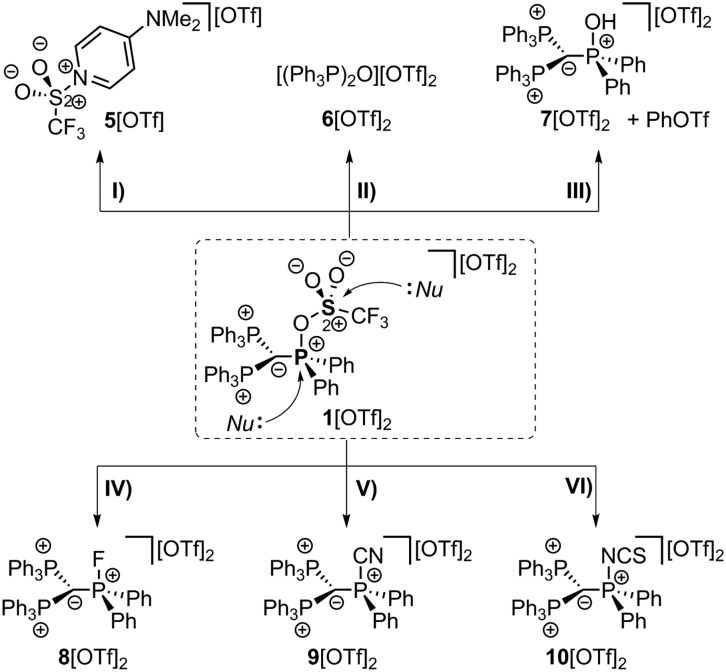

Scheme 1. Proposed synthetic route and reactivity of triflyloxyphosphonium dications of type B.

Thus, triflyloxyphosphonium dications of type B should readily undergo substitution reactions at the P(OTf) atom by releasing the weakly coordinating triflate anion (Scheme 1). In this contribution, we present a carbodiphosphorane mediated synthesis of the first triflyloxyphosphonium salt 1[OTf]2 (Scheme 2), which enables the selective synthesis of a variety of (pseudo)halophosphonium salts.

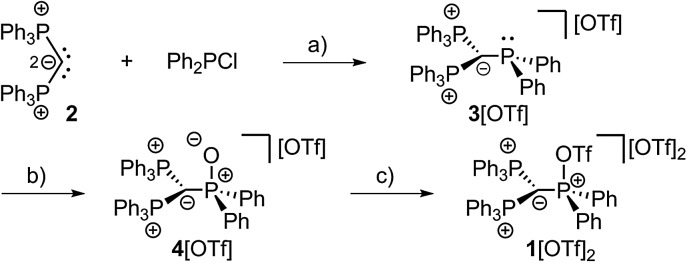

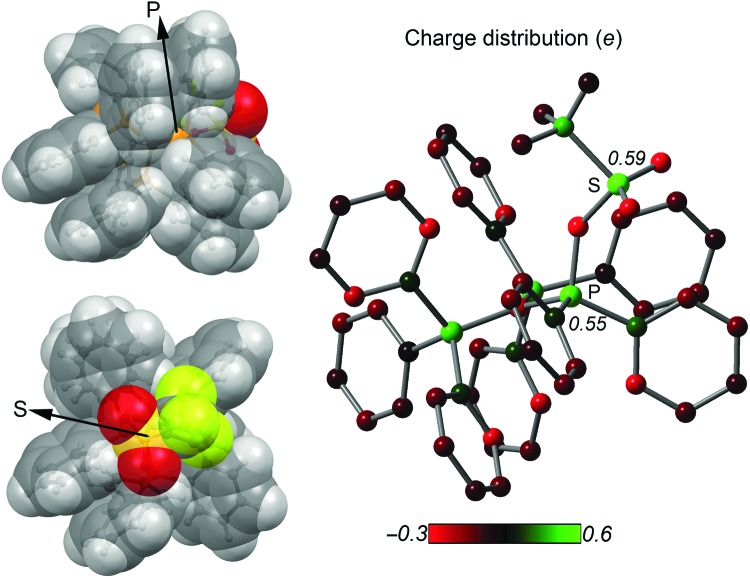

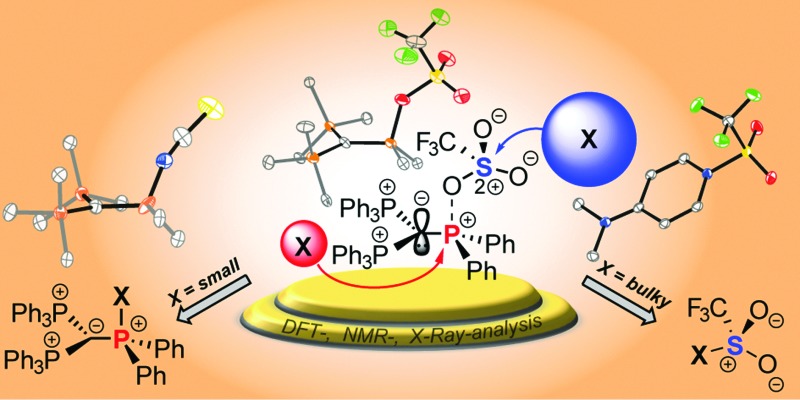

Scheme 2. Preparation of 3[OTf], 4[OTf] and 1[OTf]2; (a) +Me3SiOTf, –Me3SiCl, C6H5F, rt, 1 h, 90%; (b) +tBuO2H, –tBuOH, CH2Cl2, rt, 30 min, 97%; (c) +Tf2O, C6H5F, rt, 12 h, 98%.

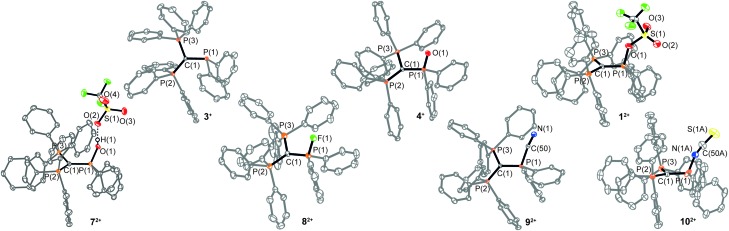

The implementation of a phosphanyl moiety onto carbodiphosphorane (Ph3P)2C (2) was already reported in 1966 as a result of the reaction of 2 with Ph2PCl.12 The formed salt 3[Cl] is conveniently converted to the triflate salt via in situ addition of Me3SiOTf. 3[OTf] is obtained as a colorless and air-stable powder in very good yields (90%, Scheme 2). The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of 3[OTf] displays the expected AX2 spin system with the triplet resonance at δ(PA) = –1.3 ppm and the doublet resonance at δ(PX) = 26.4 ppm (2 J PP = 75 Hz).13 The molecular structure of cation 3+ displays the expected pyramidalized phosphanyl moiety and the trigonal planar arrangement of the substituents around the methanide moiety (angle sum: 360.00(2)°, Fig. 1). The C(1)–P(2) and C(1)–P(3) bonds (1.751(1) Å and 1.747(1) Å) are shortened compared to other phosphonium salts (e.g. [Ph4P]+: P–C(average) 1.80(1) Å) as a result of the negative hyperconjugation from the p-type lone pair of electrons at C(1) into the σ*(P(2)/P(3)–CPh) orbitals.14 3[OTf] reacts cleanly with tBuO2H affording the phosphane oxide triflate salt 4[OTf] (yield: 96%)12 and displays, in contrast to 3[OTf], an A2X spin system with resonances observed at δ(PX) = 26.5 ppm and δ(PA) = 22.8 ppm. The 2 J PP coupling constant of 18 Hz is much smaller in magnitude compared to that of 3[OTf] (2 J PP = 75 Hz) as a result of the coupling between two tetra-coordinated P atoms.13 The molecular structure of cation 4+ (Fig. 1) displays the expected distorted tetrahedral bonding environment for the P(1) atom with a typical P–O bond length of 1.489(1) Å.15 The reaction of 4[OTf] with one equivalent of triflic anhydride (Tf2O) leads to the formation of the highly moisture sensitive triflyloxyphosphonium triflate salt 1[OTf]2 in excellent yield (98%, Scheme 2). We propose that the additional π-donor ability of the (Ph3P)2C moiety leads to a sufficient stabilization of the cation 12+ by increasing electron density at the P(1) atom, which consequently enhances the Lewis basicity of the O(1) atom. The synthesis of 1[OTf]2 succeeds also via the direct oxidation of 3[OTf] with in situ generated PhI(OTf)2,16 which serves as a strong oxidant and an OTf source at the same time. Cation 1 2+ is formed in solution in a spectroscopic yield of 73% according to 31P NMR spectroscopy. The formation of significant amounts of side products17 hampers a high yielding isolation of 1[OTf]2 and, thus, makes the two step method, according to Scheme 2, more efficient. The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of 1[OTf]2 displays an A2X spin system with a pronounced downfield shifted triplet for the PX atom (δ(PX) = 86.0 ppm; 2 J PP = 20 Hz) compared to 4[OTf]. The electron withdrawing properties of the OTf-substituent cause a deshielding of the corresponding PX atom and explain this significant shift. This effect, however, does not influence the resonance observed for the Ph3P-onio substituents (δ(PA)) = 25.8 ppm) and, thus, only a slight downfield shift of Δδ = 3.0 ppm is observed. The 19F NMR spectrum reveals two sharp singlets at δ = –71.9 ppm and –78.5 ppm for the bonded OTf-group and for the non-coordinated OTf anions, respectively. No dynamic behavior for the OTf-substituent in solution at temperatures from –28 °C to 72 °C is observed as evidenced by variable temperature 31P-/19F NMR spectroscopy.17 The molecular structure of 12+ reveals a distorted tetrahedral bonding environment at the P(1) atom with a pronounced shortening of the C(1)–P(1) bond (1.731(5) Å) and elongation of the C(1)–P(2) (1.789(5) Å) and C(1)–P(3) (1.777(5) Å) bonds, in contrast to those in cations 3+ and 4+ (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The shortening of the C(1)–P(1) bond is a result of an increased negative hyperconjugation from the p-type lone pair of electrons at C(1) into the σ*(P(1)–O(1)) orbital. This redistribution of electron densities from the C(1) lone pair in benefit to the P(1) atom may account for the strong stabilization of the electron deficient triflyloxyphosphonium moiety. The P–O bond in 12+ (P(1)–O(1) 1.676(4) Å) is exceptionally long for a typical PV–O bond (cf. Hendrickson reagent [(Ph3P)2O]2+: 1.597(3) Å, 1.598(4) Å18) but an expected consequence of the above-mentioned donation of electron density into the σ*(P(1)–O(1)) orbital (vide supra). This effect is even more pronounced by the highly electron withdrawing properties of the triflyl group – SO2CF3 – and leads to an elongated and strongly activated P–O bond. Similarly, the O(1)–S(1) bond (O(1)–S(1) 1.571(4) Å) is also elongated compared to those observed for non-coordinating triflate anions (S–O(average) 1.43(3) Å). This bonding environment at P(OTf) in cation 12+ indicates an electron deficiency at the S(1)- and P(1) atoms, which was probed in reactions with a variety of nucleophiles. The computed charge distribution in cation 12+ confirms P(1) and S(1) as the most electrophilic sites with almost identical positive charges (P(1): 0.55 e, S(1): 0.59 e, Fig. 2, right). Thus, a preference for a nucleophilic attack at the P(1) or S(1) atom by charge discrimination is not likely. However, the space-filling representation of cation 12+ (Fig. 2, left) indicates a significant difference between both electrophilic centers with regard to their accessibility. The P(1) atom is sterically shielded by the close proximity of three phenyl rings which makes it less accessible for a nucleophilic attack. In contrast, the S(1) atom of the triflyloxy moiety is by far more exposed, which consequently allows a better interaction with nucleophiles. As a consequence, a size discrimination of cation 12 + in the reaction with nucleophiles can be anticipated. To probe our hypothesis, 1[OTf]2 was reacted with selected nucleophiles (Scheme 3). Bulky substituents react preferably at the S(1) atom of cation 12 + and, thus, 1[OTf]2 gives in a quantitative reaction with 4-dimethylaminiopyridine (DMAP) the 1-triflyl-4-dimethylaminopyridinium salt 5[OTf] and 4[OTf] as a result of the nucleophilic substitution at the S(1) atom and transfer of the SO2CF3-group to DMAP (I). Two sets of single crystals of 5[OTf] suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained at different temperatures (–30 °C and 21 °C) displaying two monoclinic polymorphs that vary by their packing mode in the crystal structure (C2/c vs. P21/n; for further details, see the ESI†). Similar to the reaction with DMAP, two equivalents of triphenylphosphaneoxide (Ph3P(O)) react with 1[OTf]2 cleanly to give the Hendrickson reagent [(Ph3P)2O][OTf]2 (6[OTf]2) and 4[OTf] (II). Phenol is converted in a 1 : 1 reaction into phenyltriflate and the hydroxyphosphonium salt 7[OTf]2 (III). 7[OTf]2 displays a rare example of a hydroxyphosphonium dication and can be alternatively prepared directly via the protonation of 4[OTf] with HOTf (yield: 83%). Small nucleophiles should interact with dication 12+ at the P(1) atom preferably via elimination of the triflate anion. 1[OTf]2 reacts cleanly with AgF to give the fluorophosphonium salt 8[OTf]2 and AgOTf (IV), with Me3SiCN to the cyanophosphonium triflate 9[OTf]2 accompanied by the liberation of Me3SiOTf (V), and with NH4SCN to yield the isothiocyanatophosphonium triflate 10[OTf]2 and NH4OTf. We have computed theoretically for F–, CN–, SCN–, DMAP and Ph3P(O) both possible nucleophilic attacks (P(1) and S(1)) at the BP86-D3/def2-TZVP level of theory in a continuum solvent model (reaction energies are given in Table 2).17 The nucleophilic attacks of F–, CN– and SCN– are barrierless processes due to the dicationic nature of the electrophile. The substantial difference is that the nucleophilic attack at the P(1) atom is more exergonic than the attack at the S(1) atom (Table 2). This result further supports that small nucleophiles attack preferentially at the P(1) atom. For the sterically more demanding nucleophiles DMAP and Ph3P(O), only the attack at the S(1) atom is possible, although less favorable than the attack of the anions F–, CN– and SCN– at P(1) due to the stronger electrostatic attraction (see the ESI†). Phosphonium salts 7–10[OTf]2 could be conveniently isolated in good to very good yields (73–88%) and show in the 31P NMR spectra the characteristic A2X spin systems. The 31P NMR spectrum of 7[OTf]2 displays a triplet at δ(PX) = 50.3 ppm and a doublet at δ(PA) = 23.9 ppm (2 J PP = 21.0 Hz). The hydroxy group of 7[OTf]2 is observable in the 1H NMR spectrum, displaying a downfield shifted singlet resonance at δ(OH) = 13.93 ppm. The molecular structures of 72+–102+ were also confirmed by X-ray analysis and are depicted in Fig. 1. The molecular structure of 72+ reveals a distorted tetrahedral bonding environment at the P(1) atom.

Fig. 1. Molecular structures of 3+, 4+, 12+, 72+, 82+, 92+ and 102+ (hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity and thermal ellipsoids are displayed at 50% probability).

Table 1. Selected bond length for crystallographically characterized cations 3+, 4+, 12+, 72+, 82+, 92+ and 102+ .

| Bond length in Å | 3+ | 4+ | 12+ | 72+ | 82+ | 92+ | 102+ |

| P(1)–C(1) | 1.811(1) | 1.803(2) | 1.731(5) | 1.754(1) | 1.721(3) | 1.754(1) | 1.748(5) |

| P(2)–C(1) | 1.751(1) | 1.747(2) | 1.789(5) | 1.780(1) | 1.777(3) | 1.788(3) | 1.777(4) |

| P(3)–C(1) | 1.747(1) | 1.754(2) | 1.777(5) | 1.775(1) | 1.784(3) | 1.780(1) | 1.778(4) |

| P(1)–X | — | X = O(1) | X = O(1) | X = O(1) | X = F(1) | X = C(50) | X = N(1A) |

| 1.489(1) | 1.676(4) | 1.562(1) | 1.561(2) | 1.788(1) | 1.663(7) |

Fig. 2. Left: Two views of the space filling representation of 12+; right: Mulliken charge distribution in 12+.

Scheme 3. Reactions of 1[OTf]2 with different nucleophiles; (I) +DMAP, –4[OTf], yield (5[OTf]): 90%*; (II) +Ph3P(O), –4[OTf], quant. conversion**; (III) +PhOH, quant. conversion**; (IV) +AgF, –AgOTf, 82%*; (V) +Me3SiCN, –Me3SiOTf, 88%*, (VI) +NH4SCN, –NH4OTf, 73%*; (isolated yields are marked with *; by 31P/19F NMR spectroscopy**).17 .

Table 2. Reaction energies (in kcal mol–1) for the two possible nucleophilic attacks (P(1)- and S(1) atoms) given at the RI-BP86/def2-TZVP level of theory.

| ΔE | F– | CN– | SCN– | DMAP | Ph3P(O) |

| P(1) | –76.5 | –48.1 | –40.6 | — | — |

| S(1) | –64.4 | –40.6 | –33.0 | –21.2 | –8.3 |

| Δ(E P–E S) | 12.1 | 7.5 | 7.6 | — | — |

Due to protonation the P–O bond length (P(1)–O(1) 1.562(1) Å) is elongated compared to that of phosphane oxide 4 + but is still shorter than the P(1)–O(1) bond in 12+. A short O–H···O hydrogen bond is observed between the hydroxy group and one of the triflate anions (O(2)–H(1)···O(2) 2.549(2) Å, O(2)–H(1)···O(2) 173(3)°).19 The fluorophosphonium salt 8[OTf]2 displays in the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum a distinct dt resonance at δ(PX) = 85.9 ppm (1 J PF = 1012 Hz; 2 J PP = 21 Hz) and a dd resonance at δ(PA) = 23.8 ppm (3 J PF = 15 Hz) with a dt resonance at δ(F) = –97.5 ppm in the 19F{1H} NMR spectrum. The molecular structure of cation 82+ shows a distorted tetrahedral bonding environment for the P(F) atom with a characteristic P–F bond length of 1.561(2) Å.6 Salt 9[OTf]2 represents the first dicationic cyanophosphonium salt and displays in the 31P NMR spectrum a triplet at δ(PX) = 19.7 ppm and a doublet at δ(PA) = 25.5 ppm (2 J PP = 23 Hz). The 13C{1H} NMR spectrum reveals the expected doublet at δ(C(CN)) = 113.7 ppm (1 J CP = 85 Hz)20 and the presence of the CN group is further supported by IR and Raman spectroscopy, which both display the characteristic cyanide stretching bands at 2191(w) cm–1,21 and 2192(28) cm–1,22 respectively. The molecular structure of cation 92+ shows a distorted tetrahedral bonding environment for the P(CN) atom. The P(1)–C(50) bond (1.788(1) Å) is in the typical range for a P–CN bond length in phosphonium salts and compares well with related examples in the literature.23–25 The P(1)–C(50)–N(1) angle (171.8(1)°) is in comparison slightly more acute ([(Me2N)3PCN]+ (179.2(5)°);23 [(2,4,6-(MeO)C6H2)3PCN]+ (180.0°);24 and Ph3PCN2: (179.0(3)°).25 The 31P NMR spectrum of isothiocyanophosphonium salt 10[OTf]2 shows a triplet at δ(PX) = 36.4 ppm and a doublet at δ(PA) = 24.8 ppm (2 J PP = 22 Hz). The isothiocyanato group resonates in the 13C{1H} NMR spectrum as a doublet at δ(NCS) = 115.7 ppm (2 J CP = 21 Hz)26 and the IR spectrum shows a strong band at 1956(m) cm–1, typical for covalently bonded SCN-groups.27 Cation 102+ is the first crystallographically characterized example of an isothiocyanatophosphonium cation and displays a distorted tetrahedral bonding environment at the P(NCS) atom. Its P(1)–N(1A) bond length (1.663(7) Å) is shorter than those of neutral tetra-coordinated isothiocyanate-substituted PV compounds ((ImN)2P(NCS)S (ImN = 1,3-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)-imidazol-2-imine): 1.728(1) Å,28 (ferrocene)P(NMe2)(NCS)S: 1.700(5) Å);29 a slightly more acute P(1)–N(1A)–C(50A) angle (148.9(6)°) is observed ((ImN)2P(NCS)S: 162.0(1)°, (ferrocene)P(NMe)2(NCS)S: 156.5(6)°). Analogously to dications 12+ and 72+–92+, a shortened C(1)–P(1) bond is observed as the result of the electronic congestion of the substituents (Table 1).

In summary, the preparation of the triflyloxyphosphonium dication 12+ bearing two electrophilic sites that can be selectively addressed by nucleophiles has been achieved. Thus, large nucleophiles react exclusively with the triflyl-moiety via the transfer of the SO2CF2 group, whereas the reaction with small nucleophiles results in a substitution reaction at the P(OTf) atom, consequently releasing the triflate anion. This renders dication 12+ a suitable reaction platform for the synthesis of functionalized phosphonium salts, as demonstrated by the isolation of various (pseudo)halophosphonium dications. The facile functionalization based on dication 12+ allows the precise design and preparation of valuable Lewis acidic phosphonium cations.

This work was supported by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie (FCI, Kekulé scholarship for F. H.) and ERC (ERC starting grant SynPhos: 307616). A. B. and A. F. thank DGICYT of Spain (projects CTQ2014-57393-C2-1-P and CONSOLIDER INGENIO CSD2010–00065, FEDER funds) for funding.

Footnotes

References

- (a) Petz W. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015;291:1. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tonner F., Oxler F., Neumüller B., Petz W., Frenking G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:8038. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ramirez F., Desai N. B., Hansen B., McKelvie N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1961;83:3539. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Chen W.-C., Lee C.-Y., Lin B.-C., Hsu Y.-C., Shen J.-S., Hsu C.-P., Yap G. P. A., Ong T.-G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;136:914. doi: 10.1021/ja4120852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Khan S., Gopakumar G., Thiwl W., Alcarazo M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:5644. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Inés B., Patil M., Carreras J., Goddard R., Thiel W., Alcarazo M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:8400. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Tay M. Q. Y., Ilic G., Zwanziger U. W., Lu Y., Ganguly R., Ricard L., Frison G., Carmichael D., Vidovic D. Organometallics. 2016;35:439. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tay M. Q. Y., Lu Y., Ganguly R., Vidovic D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:3132. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Bayne J. M., Stephan D. W. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:765. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00516g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gabbaï F. P. Science. 2013;341:1348. doi: 10.1126/science.1244423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hounjet L. J., Caputo C. B., Stephan D. W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:4714. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo C. B., Winkelhaus D., Dobrovetsky R., Hounjet L. J., Stephan D. W. Dalton Trans. 2015;44:12256. doi: 10.1039/c5dt00217f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Pérez M., Hounjet L. J., Caputo C. B., Dobrovetsky R., Stephan D. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:18308. doi: 10.1021/ja410379x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Caputo C. B., Hounjet L. J., Dobrovetsky R., Stephan D. W. Science. 2013;341:1374. doi: 10.1126/science.1241764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Werner T. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009;351:1469. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Winkelhaus D., Holthausen M. H., Dobrovetsky R., Stephan D. W. Chem. Sci. 2015;6:6367. doi: 10.1039/c5sc02336j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Weigand J. J., Burford N., Decken A., Schulz A. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2007:4868–4872. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Zhao H., Leamer L. A., Gabbaï F. P. Dalton Trans. 2013;42:8164. doi: 10.1039/c3dt50491c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kim Y., Gabbaï F. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3363. doi: 10.1021/ja8091467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lee M. H., Agou T., Kobayashi J., Kawashima T., Gabbaï F. P. Chem. Commun. 2007:1133–1135. doi: 10.1039/b616814k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Robertson A. P. M., Burford N., McDonald R., Ferguson M. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:3480. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Donath M., Bodensteiner M., Weigand J. J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2014;20:17306. doi: 10.1002/chem.201405196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Hendrickson J. B., Schwartzman S. M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975;4:277. [Google Scholar]; (b) Aaberg A., Gramstad T., Husebye S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979;24:2263. [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of 3[Cl] and subsequent oxidation with tBuO2H to give 4[Cl] are reported in the following ref.: Birum G. H., Matthews C. N., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1966, 88 , 4198 . [Google Scholar]

- For other 2 J PP coupling constants, see: Caminade A.-M., Ocando E., Majoral J.-P., Cristante M., Bertrand G., Inorg. Chem., 1986, 25 , 712 . [Google Scholar]

- Leyssens T., Peeters D. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:2725. doi: 10.1021/jo7025756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandoli G., Bortolozzo G., Clemente D. A., Croatto U., Panattoni C. J. Chem. Soc. A. 1970:2778. [Google Scholar]

- Pell T. P., Chouchman S. A., Ibrahim S., Wilson D. J. D., Smith B. J., Barnard P. J., Dutton J. L. Inorg. Chem. 2012;51:13034. doi: 10.1021/ic302176f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For details, see ESI

- You S.-L., Razavi H., Kelly J. W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003;42:83. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey P. A. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2001;39:S190. [Google Scholar]

- Weigand J. J., Feldmann K.-O., Henne F. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:16321. doi: 10.1021/ja106172d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitson R. E., Griffith N. E. Anal. Chem. 1952;24:334. [Google Scholar]

- Gou H., Yonke B. L., Epshteyn A., Kim D. Y., Smith J. S., Strobel T. A. J. Chem. Phys. 2015;142:194503. doi: 10.1063/1.4919640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes N. A., Godfrey S. M., Halton R. T. A., Pritchard R. G., Safi Z., Sheffield J. M. Dalton Trans. 2007:3252. doi: 10.1039/b705651f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes N. A., Godfrey S. M., Halton R. T. A., Law S., Prichard R. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:1272. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey S. M., McAuliffe C. A., Pritchard R. G., Sheffield J. M. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1998:1919. [Google Scholar]

- Giffard M., Cousseau J., Martin G. J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2. 1985:157. [Google Scholar]

- Lieber E., Rao C. N. R., Ramachandran J. Spectrochim. Acta. 1959;13:296. [Google Scholar]

- Dielmann F., Bertrand G. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015;21:191. doi: 10.1002/chem.201405430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman M. R. S., Slawin A. M. Z., Woollins J. D. Chem. Commun. 1997:1269. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.