The heterogeneous catalase-like activity of ionic crystals consisting of AuI

4CoIII

2 complex cations is studied along with their surface morphologies and oxidation states.

The heterogeneous catalase-like activity of ionic crystals consisting of AuI

4CoIII

2 complex cations is studied along with their surface morphologies and oxidation states.

Abstract

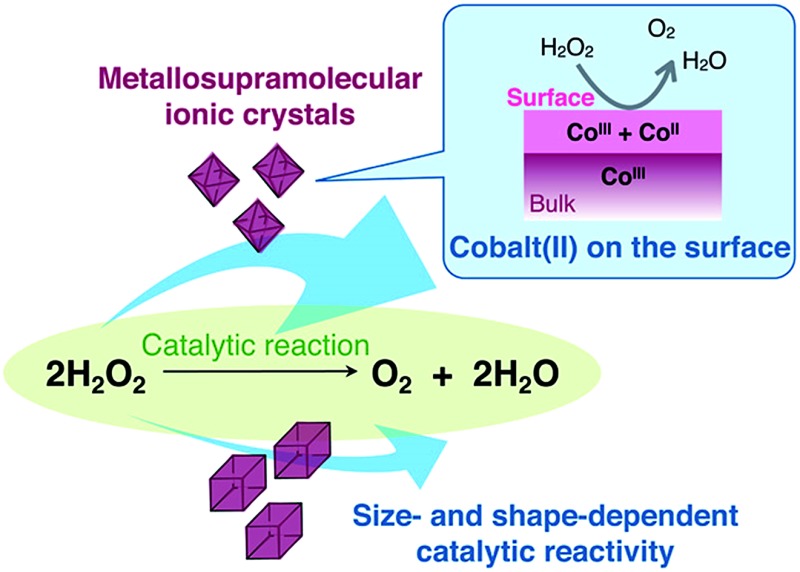

Unique heterogeneous catalase-like activity was observed for metallosupramolecular ionic crystals [AuI 4CoIII 2(dppe)2(d-pen)4]Xn ([1]Xn; dppe = 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)ethane; d-pen = d-penicillaminate; Xn = (Cl–)2, (ClO4 –)2, (NO3 –)2 or SO4 2–) consisting of AuI 4CoIII 2 complex cations, [1]2+, and inorganic anions, X– or X2–. Treatment of the ionic crystals with an aqueous H2O2 solution led to considerable O2 evolution with a high turnover frequency of 1.4 × 105 h–1 for the heterogeneous cobalt complexes, which was dependent on their size and shape as well as the arrangement of cationic and anionic species. These dependencies were rationalized by the presence of cobalt(ii) centers on the crystal surface and their efficient exposure on the (111) plane rather than the (100) plane based on morphological and theoretical studies.

Introduction

Heterogeneous catalysts have been developed for industrial applications because of their facile handling, high durability and reusability.1 Various approaches, such as increasing the surface area by decreasing the particle size,2 attachment to mesoporous carriers,3 introduction of heterogeneous elements, enlargement of dispersion4 and modification of the crystal surface, have been used to control and improve their catalytic activities.5 In particular, the catalytic activities of metals or metal oxides with high durability have been improved by controlling the size and shape of the crystals.6 Compared to metal and metal oxide catalysts, catalysts consisting of coordination compounds (metal complexes) have certain advantages with respect to the precise modulation of their structures and properties through modification of the ligands employed.7 However, the relationship between the size and shape of the crystals and the catalytic activities of coordination compounds has rarely been investigated.

One well-known catalytic reaction is the disproportionation of hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen, which is similar to the catalase reaction in living organisms (eqn (1)).8

| 2H2O2 → O2 + 2H2O | 1 |

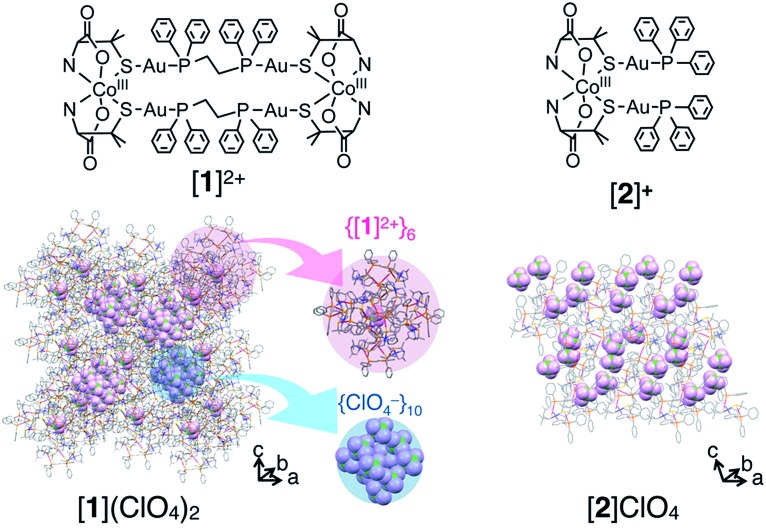

This catalase-like activity has been observed for many coordination compounds under homogeneous and/or heterogeneous conditions. However, only a few cobalt(ii) complexes have been reported to show catalase-like activity under heterogeneous conditions.9 Furthermore, no reports exist on the catalase-like activity of cobalt(iii) complexes except one report of low activity under homogeneous conditions.10 Herein, we report that metallosupramolecular ionic crystals containing cobalt(iii) centers, [AuI 4CoIII 2(dppe)2(d-pen)4]Xn ([1]Xn, dppe = 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)ethane, d-pen = d-penicillaminate, Xn = (Cl–)2, (ClO4 –)2 (NO3 –)2 or SO4 2–, Fig. 1), which were recently synthesized and structurally characterized,11 exhibit high catalase-like activity under heterogeneous conditions. This class of ionic crystals, which we refer to as ‘non-coulombic ionic solids (NCIS)’, consists of AuI 4CoIII 2 hexanuclear complex cations, [1]2+, and inorganic anions, X– or X2–, and adopts an unusual non-alternate arrangement of cationic and anionic species governed by non-coulombic interactions; complex cations [1]2+ are self-assembled into octahedron-shaped cationic supramolecules, {[1]2+}6, and anions X– or X2– are aggregated into adamantane- or octahedron-shaped anionic clusters, {X–}10 or {X2–}6 (Fig. 1, S1 and S2 in the ESI†).11 Mechanistic insight into the appearance of catalase-like activity for crystals of [1]Xn, together with its size and shape dependency, is also reported.

Fig. 1. Structures of the AuI 4CoIII 2 complex [AuI 4CoIII 2(dppe)2(d-pen)4]2+ ([1]2+) and AuI 2CoIII complex [CoIII{AuI(PPh3)(d-pen)}2]+ ([2]+) and crystal packing structures of [1](ClO4)2 and [2]ClO4.11,15 An anion is accommodated at the center of {[1]2+}6. H2O molecules are omitted for clarity.

Results and discussion

Catalase-like activity of ionic crystals of [1]Xn

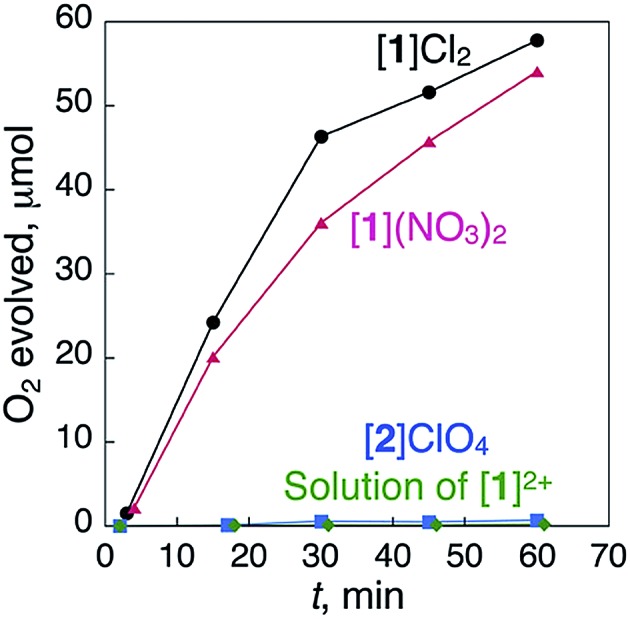

When ionic crystals of the octahedron-shaped [1]Cl2 or [1](NO3)2 were soaked in a 5% aqueous solution of H2O2 at room temperature without stirring, the generation of bubbles was observed within a few minutes. Based on the gas chromatography (GC) results, we confirmed that this phenomenon is due to the evolution of O2 gas caused by a heterogeneous catalase-like reaction (Fig. 2).12,13 Similar treatment of aqueous H2O2 with ionic crystals of the AuI 4CrIII 2 hexanuclear complexes,11 [Au4Cr2(dppe)2(d-pen)4]Cl2, which are isomorphous with [1]Cl2, showed no significant evolution of O2 gas (Fig. S4†). The same result was obtained when the digold(i) complex, [Au2(dppe)(d-Hpen)2],11 which is a precursor to the preparation of [1]Cl2 and [1](NO3)2, was treated with aqueous H2O2 (Fig. S5†). Thus, the cobalt centers in [1]Cl2 or [1](NO3)2, rather than gold centers, are the active sites of this catalytic reaction. One may suspect that Co0 nanoparticles that act as catalysts are produced over the course of the reaction.14 However, no peaks attributed to Co0 were detected near 778 eV in the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of the crystal [1]Cl2 after treatment with H2O2 (Fig. S6†),15 which indicates the absence of Co0 species.

Fig. 2. Time-dependent profiles of the evolution of O2 during treatment with a catalytic amount of [1]Cl2 (5.0 mg), [1](NO3)2 (4.9 mg), [2]ClO4 (5.0 mg) and a homogeneous saturated solution of [1]Cl2 in H2O (0.83 mL) with 5% aqueous H2O2 (1.00 mL total) at 298 K.

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) measurements revealed that the crystallinity of [1]Cl2 and [1](NO3)2 is retained after treatment with H2O2 (Fig. S7†). The durability of [1]Cl2 was revealed by the 1H and 31P NMR and XPS measurements of the samples after the reaction (Fig. S6 and S8†). Furthermore, the second reaction of the [1]Cl2 crystals, which were collected after reaction for 60 min, had an activity comparable to that in the first run, thus indicating reusability (Fig. S9†).

The turnover number (TON) and frequency (TOF) of the [1]Cl2/[1](NO3)2 crystals at 15 min were estimated as 3.2 × 104/3.4 × 104 and 1.2 × 105/1.4 × 105 h–1, respectively, assuming that only the cobalt centers located on the crystal surface are involved in the reaction.16 Notably, the TOF values for [1]Cl2 and [1](NO3)2 were much higher than that for cobalt complexes with the highest heterogeneous catalase-like activity at room temperature, as has been reported previously (5.5 × 103 h–1).9b,17

To determine the effect of the arrangement of cationic and anionic species in the crystal on the appearance of the catalase-like activity, ionic crystals of [CoIII{AuI(PPh3)(d-pen)}2]ClO4 (ref. 18) ([2]ClO4, Fig. 1), which has the same coordination environment around the CoIII center as that in [1]2+ but adopts a typical alternating arrangement of cations and anions in the crystal, were treated with aqueous H2O2 under the same conditions (Fig. 2). Remarkably, no evolution of O2 gas was observed with this treatment, which was also the case during treatment of a saturated solution of [1]Cl2 in H2O with aqueous H2O2.12 Thus, the arrangement of cationic and anionic species plays a key role in the appearance of the heterogeneous catalase-like activity of the [1]Cl2 and [1](NO3)2 crystals.

Since the activity of heterogeneous catalysts often depends on the surface area, we examined the catalase-like activity of [1]Cl2 and [1](NO3)2 using crystals of different sizes (Fig. S10 and S11†).19 The use of small crystals (0.4 × 0.4 × 0.4 mm for [1]Cl2 and 0.05 × 0.05 × 0.05 mm for [1](NO3)2) led to greater evolution of O2 gas compared to the use of large crystals (1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm for [1]Cl2 and [1](NO3)2), which is expected from the larger surface area per unit mass. The TOFs at 15 min, which were calculated by considering the number of Co atoms on the crystal surface, were equivalent for the small and large crystals. Furthermore, a proportional relationship between the catalytic activities and the amounts of crystal used was observed, which is consistent with the surface-area dependency of the catalytic activities (Fig. S12†).

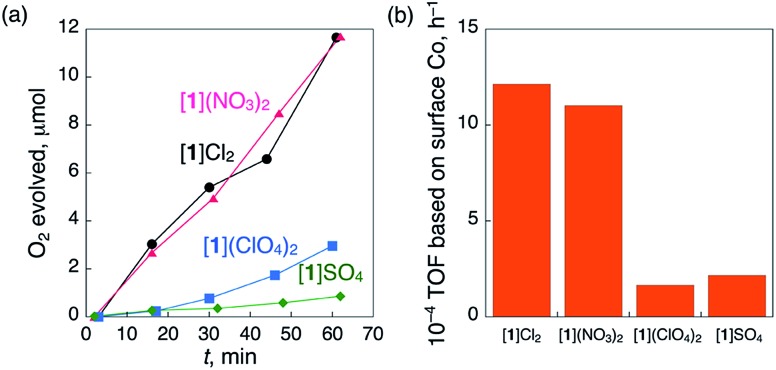

We observed that the crystal shapes of [1](ClO4)2 and [1]SO4 are cubic, unlike the octahedral shape of the [1]Cl2 and [1](NO3)2 crystals. To determine the difference in the catalase-like activities between the octahedral and cubic crystals, the same size of crystals (ca. 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm) of these compounds were treated with aqueous H2O2 under the same conditions, eliminating the size-dependent effect (Fig. S13†). As expected, all the crystals showed O2 evolution, which was confirmed by GC measurements (Fig. 3a). The TOFs at 15 min for the octahedral crystals [1]Cl2 and [1](NO3)2 were more than 5 times higher than those for the cubic crystals [1](ClO4)2 and [1]SO4 (Fig. 3b). No significant difference in the TOF values was observed between [1]Cl2 and [1](NO3)2 or between [1](ClO4)2 and [1]SO4. This result clearly indicates that the heterogeneous catalytic activity of [1]Xn is highly dependent on the crystal shape, rather than the type of anionic species in the crystal.

Fig. 3. (a) Time-dependent profiles of the evolution of O2 during treatment with a catalytic amount of 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm-sized crystals of [1]Cl2 (5.2 mg), [1](NO3)2 (5.1 mg), [1](ClO4)2 (4.8 mg) or [1]SO4 (5.3 mg) with 5% aqueous H2O2 (1.00 mL) at 298 K and (b) TOF calculated based on the number of surface Co atoms at 15 min.

Crystal surface morphology and oxidation state of cobalt centers of [1]Xn

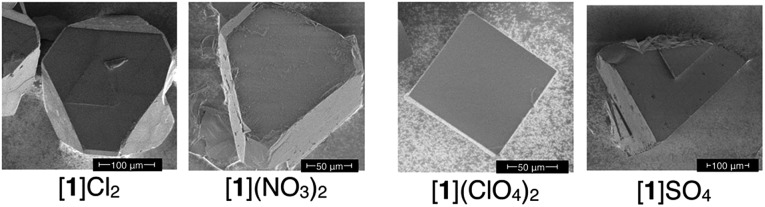

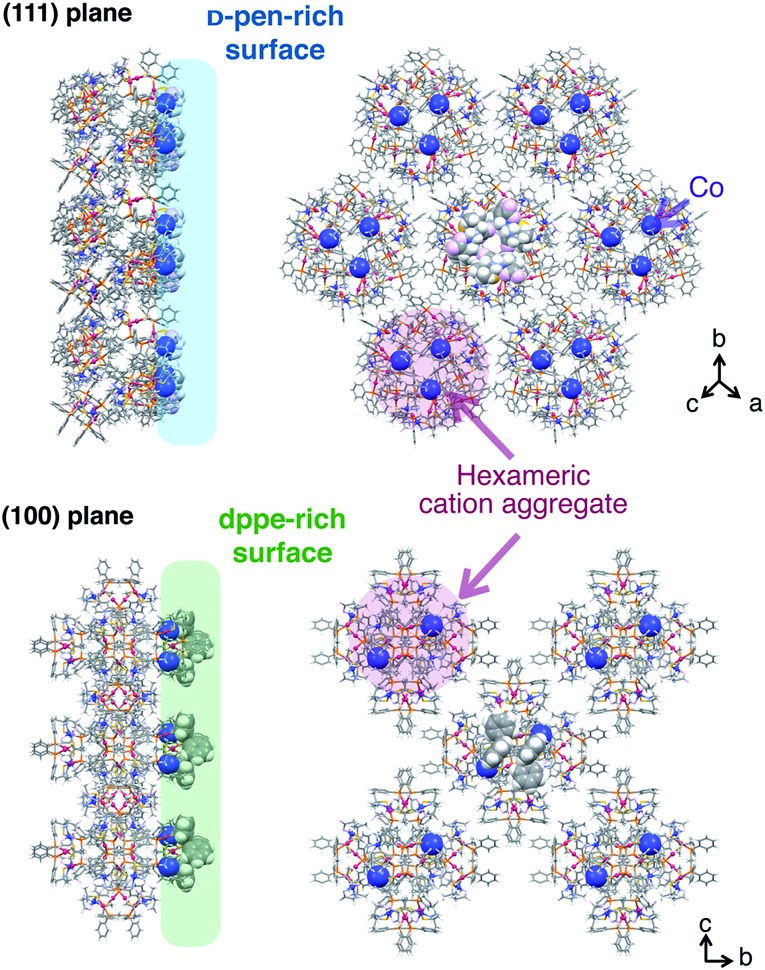

The crystal-shape dependency of the catalase-like activity of [1]Xn can be discussed from the viewpoint of the surface morphology. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the crystal surfaces revealed that the crystal growth of the (111) plane is dominant for [1]Cl2 and [1](NO3)2, whereas growth of the (100) plane is dominant for [1](ClO4)2 and [1]SO4, as expected based on their macroscopic crystal shapes (Fig. 4).6 Thus, it is reasonable to assume that the catalytic activity on the (111) plane is higher than that on the (100) plane, considering the higher activity of the [1]Cl2 and [1](NO3)2 crystals. This tendency contrasts with the catalytic activities of platinum nanoparticles, for which the (100) plane has higher activity than the (111) plane; this phenomenon has been ascribed to a looser alignment of platinum atoms on the (100) plane.6 The surface structure of each crystal plane of [1]Xn, determined by single-crystal X-ray analysis, is shown in Fig. 5.11 The (111) plane is a d-pen-rich surface, and the cobalt centers are fully exposed by the easy dissociation of the carboxyl group of d-pen, as discussed below. On the other hand, the (100) plane is a dppe-rich surface, and the cobalt centers are much less exposed. Thus, the (111) plane is advantageous due to the exposure of the cobalt centers on the crystal surface, which leads to high catalytic activity.

Fig. 4. SEM images of crystals [1]Cl2, [1](NO3)2, [1](ClO4)2, and [1]SO4.

Fig. 5. Side and top views of the arrangement of cationic supramolecular octahedrons {[1]2+}6 on the crystal surface of the (100) plane and the (111) plane.11 .

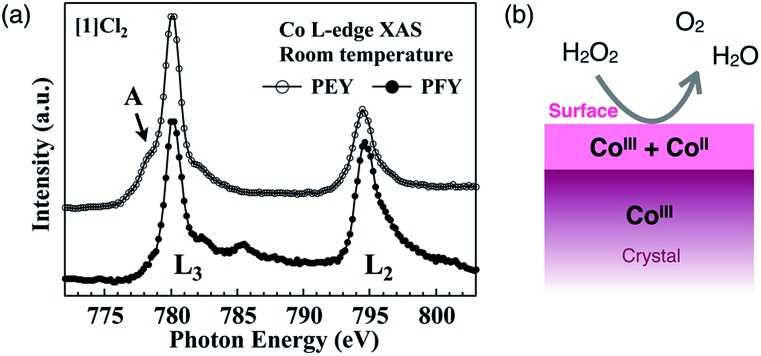

Here, we reconsider the oxidation state of the cobalt centers by focusing on the crystal surface. Cobalt centers in [1]Xn have a +III oxidation state in the crystal as well as in solution. Consistent with this, in the partial fluorescence yield (PFY) mode of X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), which is appropriate for bulk-layer observations, the crystal [1]Cl2 exhibited a single L3-edge peak at 780 eV due to cobalt(iii) species (Fig. 6a). However, in the partial electron yield (PEY) mode of XAS, which is appropriate for surface-layer observations, a clear shoulder (mark A) was observed at a lower energy of the L3-edge peak. The presence of this shoulder is indicative of the presence of cobalt(ii) species;20–22 therefore, the cobalt species located on the crystal surface at least partially exist in a +II oxidation state, although cobalt(iii) species are dominant in the bulk sample (Fig. 6b).23 This is supported by the EPR spectra of crystal [1]Cl2 at 4 K, which showed a very weak, broad signal at approximately g = 6 that is assigned to cobalt(ii).24 For [2]ClO4, which does not exhibit catalase-like activity, the EPR-silent state suggests the absence of cobalt(ii). It is quite reasonable that the aggregated cluster structure of inorganic anions in [1]Xn cannot be maintained on the crystal surface due to high repulsive energy among inorganic anions. This disruption of the aggregated anionic cluster structure should generate defects of inorganic anions, which in turn, leads to the reduction of cobalt(iii) to cobalt(ii) on the crystal surface to balance the total charge of the ionic crystal. Thus, the presence of cobalt species with a +II oxidation state, which are efficiently exposed at the (111) surface of the crystal, is key to the high catalase-like activity of the octahedral crystals [1]Cl2 and [1](NO3)2.

Fig. 6. (a) Co L-edge XAS of [1]Cl2 measured in the PEY and PFY modes at 298 K and (b) the estimated oxidation states of Co in the bulk and at the surface of the crystal [1]Xn.

The mechanism of the catalase-like reaction of [1]Xn

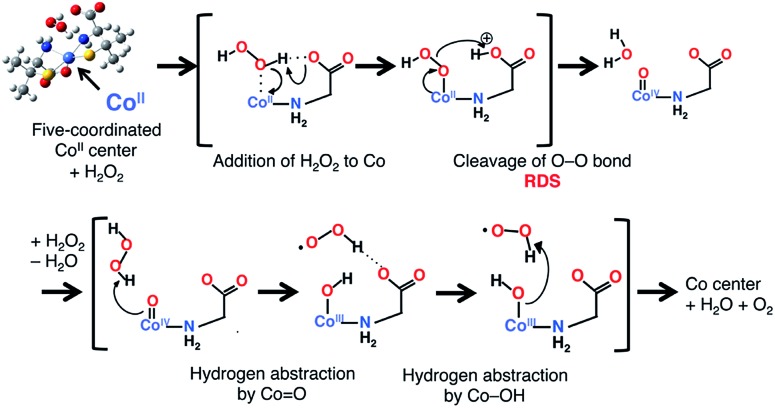

The mechanism of the catalase-like reaction in this system was estimated as follows, based on the mechanism proposed for the iron(iii) center of native catalase25 but replacing the redox active site from iron to cobalt and the deprotonation site from histidine to carboxylate (Scheme 1). In the first step of this reaction, an H2O2 molecule approaches an octahedral cobalt(ii) center, with the concomitant dissociation of a carboxyl group to form a five-coordinated cobalt(ii) center. The carboxylate group acts as a base in the deprotonation of the H2O2 molecule, giving rise to a Co–OOH intermediate. The next step involves the formation of an oxo-cobalt(iv) center and the release of an H2O molecule via heterolytic O–O bond cleavage. Finally, another H2O2 molecule attacks the oxo-cobalt(iv) center to produce the original octahedral cobalt(ii) center, with the concomitant release of H2O and O2 molecules during the formation of a hydroxo-cobalt(iii) center and an HOO˙ radical. Each transition state was calculated with the effect of solvent (H2O) at the UB3LYP-D/6-31G* level,26 which revealed that the O–O bond cleavage is the rate-determining step (RDS) with an activation energy of 21.2 kcal mol–1 relative to the substrate complex (Fig. S14†). We also calculated each transition state of the cobalt(iii) model, in which the cobalt(ii) center is replaced by a cobalt(iii) center. In the cobalt(iii) model, the activation energy of the RDS (O–O bond cleavage) was calculated as 26.7 kcal mol–1, which is higher than that in the cobalt(ii) model (Fig. S15†). This result indicates that the cobalt(ii) model is preferable for this catalase-like reaction.

Scheme 1. The proposed mechanism of the catalase-like catalytic reaction of [1]Xn. Only the main parts of the Co center and substrates are shown for clarity.

Conclusions

We showed that [1]Xn ionic crystals, which consist of AuI 4CoIII 2 complex cations ([1]2+) and inorganic anions (X = Cl–, NO3 –, ClO4 –, and SO4 2–), act as heterogeneous catalysts for a catalase-like reaction. To our knowledge, this is the first example of cobalt(iii) coordination compounds that exhibit catalase-like activity under heterogeneous conditions. Of note is the remarkably high catalytic activity, which is dependent on the crystal shape (octahedral vs. cubic) rather than the charge (–1 vs. –2) and the geometry of the inorganic anions. This is due to the unusual arrangement of cations and anions in the crystal [1]Xn, leading to the generation of cobalt(ii) centers on the crystal surface, which are efficiently exposed on the (111) plane with readily dissociated carboxyl groups compared to the (100) plane. This study demonstrated that the oxidation state and exposure of metal centers on the crystal surface that are required for heterogeneous catalytic activity can be controlled via the arrangement of cationic and anionic components as well as the crystal shape and morphology. These results provide significant insight into the future design and creation of various heterogeneous catalysts based on ionic crystals.

Experimental

Materials

Chemicals were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification. Aqueous solutions of hydrogen peroxide (30 wt%) were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries. Ultra-pure water was obtained from a Millipore Direct-Q3 UV water purification system, wherein the electronic conductance was 18.2 MΩ cm–1. [AuI 4CoIII 2(dppe)2(d-pen)4]Xn ([1]Xn, Xn = (Cl–)2, (ClO4 –)2, (NO3 –)2 or SO4 2–), [Au4Cr2(dppe)2(d-pen)4]Cl2, [CoIII{AuI(PPh3)(d-pen)}2]ClO4 ([2]ClO4) and [Au2(dppe)(d-Hpen)2] were prepared according to the methods reported in the literature.11a,18

Catalase-like catalytic disproportionation of hydrogen peroxide

A typical procedure for the catalase-like catalytic disproportionation of hydrogen peroxide is as follows. A vial containing 1.0 mL of 5 wt% aqueous H2O2 and another vial containing [1]Cl2 (5.0 mg) were sealed with rubber septa. The two vials were carefully deaerated by bubbling Ar for 15 min. The aqueous H2O2 solution was transferred to the vial containing crystals via a Teflon tube to start the reaction without stirring at 298 K. At each reaction time, 100 μL of Ar gas was injected into the vial, and the same volume of gas in the headspace was then sampled by a gastight syringe and quantified on a Shimadzu GC-17A gas chromatograph (GC) [Ar carrier gas, capillary column with molecular sieves (Agilent Technologies 19094PMS0, 30 m × 0.53 mm), 313 K] equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). Microscopic observation of the crystal sizes and filtration treatment were performed as needed.

ICP-AES measurements

ICP-AES was measured on a Shimadzu ICPS-8100. The samples were obtained by filtration of the reaction mixture at 20–30 min in conditions similar to the reaction for GC measurements.

XPS measurements

XPS spectra were measured on a Kratos Axis 165x with a 165 mm hemispherical electron energy analyzer. The incident radiation was a Mg-Kα X-ray (1253.6 eV) at 120 W (12 kV, 10 mA), and a charge neutralizer was turned on for acquisition. Each sample was mounted on a stainless-steel stage with double-sided carbon scotch tape. The binding energy of each element was corrected using the C 1s peak (284.5 eV) from the residual carbon.

NMR measurements

1H and 31P NMR spectra were measured on an ECA 500 spectrometer at 298 K. The NMR spectra were calibrated with TMS (methanol-d 4) = 0 ppm as an internal standard.

PXRD measurements

High-quality powder X-ray diffractions were recorded at room temperature, in transmission mode [synchrotron radiation λ = 0.999139(2) Å; 0° ≤ 2θ ≤ 30°; step width = 0.006°; data collection time = 30 s] on a diffractometer equipped with a MYTHEN microstrip X-ray detector (Dectris Ltd.) at the SPring-8 BL02B2 beamline. The crystals were loaded into glass capillary tubes (diameter = 0.3 mm), and the samples were rotated during the measurements.

SEM measurements

SEM observations were performed on an FEI Magellan 400L instrument at 5 × 10–5 Pa. The working distance was set to 1.9–2.7 mm. Secondary electrons were collected with an Everhart-Thornley detector. The observations were performed at a beam landing voltage of 200 or 1000 V, and 200 V imaging was performed by applying 800 V of the beam deceleration bias onto the sample against the primary electron beam accelerated at 1 kV.

EPR measurements

The sample for EPR was prepared by flowing N2 for 15 min through a Teflon tube to the crystals in a quartz EPR tube (2.0 mm i.d.). EPR spectra of the solutions were obtained on a JEOL X-band spectrometer (JES-FA200) at 4 K. The g value was calibrated using a Mn2+ marker. The EPR spectra were obtained under non-saturating microwave power conditions. The magnitude of modulation was chosen to optimize the resolution and signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio of the observed spectra.

XAS measurements21

The XAS measurements were carried out at BL-11 of the Synchrotron Radiation Center at Ritsumeikan University, Japan. In this beamline, so-called varied-line-spacing plane gratings were employed to supply monochromatic photons with hν = 40–1000 eV. The Co L2,3-edge XAS spectra (hν = 760–810 eV), were taken simultaneously in the partial fluorescence yield (PFY) and partial electron yield (PEY) modes with a photon energy resolution of ∼300 meV. For the Co L2,3-edge XAS measurements, the luminescence with hν = 700–950 eV, including the Co L lines, was detected as a signal. On the other hand, in PEY mode, the microchannel plate (MCP) for detecting the Auger and secondary electrons was set in the 45°-depression to the photon propagation. On the front of the MCP, a gold mesh was installed to enable the application of a voltage. We applied the voltage of –550 V to the mesh for the Co L2,3-edge measurements in order to suppress a strong background caused by the C, N and O K-edge absorptions in the spectra. The powder-like single-crystalline samples of [1]Cl2 and [2]ClO4 were thinly expanded on the conductive carbon tape attached on the sample holder in air before transferring them to the vacuum chamber. We repeatedly measured the spectra on the same and different sample positions to confirm the data reproducibility with neither serious radiation damage nor a sample-position dependence of the Co L2,3-edge XAS spectra. The measurements were performed at room temperature. Energy values were calibrated with the top of the L3-edge peak of LiCoIIIO3 (780.32 eV).

Theoretical calculations

Geometry optimizations were carried out at the UB3LYP-D/6-31G* level of theory for each transition state, as implemented in Gaussian 09, revision C.01.26a The effect of solvent (H2O) was included implicitly using the polarizable continuum model (PCM)26c with the cavity constructed by the universal force-field (UFF) bond radii. The charges and spin multiplicities of the Co center models in the initial state were –2 and 4 for the CoII center model and –1 and 1 for the CoIII center model, respectively.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by CREST, JST. One of the authors (M. Yamada) acknowledges the Futaba Electronics Memorial Foundation. K. Yamagami and T. Saito were supported by the Program for Leading Graduate Schools “Interactive Materials Science Cadet Program”. The synchrotron radiation experiments were performed at the BL02B2 of SPring-8 with the approval of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (JASRI) (Proposal No. 2015B1241). The soft XAS study was supported by the Project for Creation of Research Platforms and Sharing of Advanced Research Infrastructure, Japan (Proposal No. R1511). We appreciate Prof. Dr. Mitsutaka Okumura (Osaka University) and Prof. Dr. Shunichi Fukuzumi (Ewha Womans University and Meijo University) for their support with the theoretical calculations and the catalytic reactions, respectively, and fruitful discussions.

Footnotes

References

- (a) Fukuzumi S., Ohkubo K. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2015;4:836–845. [Google Scholar]; (c) Fukuzumi S., Yamada Y. ChemSusChem. 2013;6:1834–1847. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201300361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Copéret C., Comas-Vives A., Conley M. P., Estes D. P., Fedorov A., Mougel V., Nagae H., Núñez-Zarur F., Zhizhko P. A. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:323–421. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Corma A., García H., Llabrés i Xamena F. X. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:4606–4655. doi: 10.1021/cr9003924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Linsebigler A. L., Lu G., Yates J. T. Chem. Rev. 1995;95:735–758. [Google Scholar]; (g) Henry C. R. Surf. Sci. Rep. 1998;31:231–325. [Google Scholar]; (h) Mizuno N., Misono M. Chem. Rev. 1998;98:199–217. doi: 10.1021/cr960401q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Ertl G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:3524–3535. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Zhang L., Wang B., Ding Y., Wen G., Hamid S. B. A., Su D. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016;6:1003–1006. [Google Scholar]; (b) Li G., Jin R. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:1749–1758. doi: 10.1021/ar300213z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M., Karlin K. D., Fukuzumi S. Chem. Sci. 2016;7:2856–2863. doi: 10.1039/c5sc04312c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuld S., Thorhauge M., Falsig H., Elkjær C. F., Helveg S., Chorkendorff I., Sehested J. Science. 2016;352:969–974. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf0718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauermann S., Nilius N., Shaikhutdinov S., Freund H.-J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:1673–1681. doi: 10.1021/ar300225s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Kotani H., Hanazaki R., Ohkubo K., Yamada Y., Fukuzumi S. Chem.–Eur. J. 2011;17:2777–2785. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen Z., Kronawitter C. X., Koel B. E. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015;17:29387–29393. doi: 10.1039/c5cp02876k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Berrisford D. J., Bolm C., Sharpless K. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1995;34:1059–1070. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tolman C. A. Chem. Rev. 1977;77:313–348. [Google Scholar]; (c) Komarov I. V., Börner A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40:1197–1200. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010401)40:7<1197::aid-anie1197>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso-Prieto M., Vidossich P., Rovira C. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012;525:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Shivankar V. S., Thakkar N. V. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2005;64:496–503. [Google Scholar]; (b) Prasad R. V., Thakkar N. V. J. Mol. Catal. 1994;92:9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pires B. M., Silva D. M., Visentin L. C., Rodrigues B. L., Carvalho N. M. F., Faria R. B. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0137926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Lee R., Igashira-Kamiyama A., Okumura M., Konno T. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2013;86:908–920. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yoshinari N., Konno T. Chem. Rec. 2016;16:1647–1663. doi: 10.1002/tcr.201600026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lee R., Igashira-Kamiyama A., Motoyoshi H., Konno T. CrystEngComm. 2012;14:1936–1938. [Google Scholar]

- The saturated solution of [1]Cl2 (0.18 mM) was produced by standing crystals [1]Cl2 in H2O overnight (Table S1 in the ESI)

- The O2 evolution was completely stopped when the crystals of [1]Cl2 were removed from the reaction mixture (Fig. S3). The ICP-AES showed that only a quite small portion of the crystals (<0.2% for [1]Cl2, <0.03% for [1](NO3)2) was dissolved during the reaction (Table S2)

- Gual A., Godard C., Castillón S., Curulla-Ferré D., Claver C. Catal. Today. 2012;183:154–171. [Google Scholar]

- Moulder J. F., Stikle W. F., Sobol P. E. and Bomben K. D., in Handbook of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy, ed. J. Chastain and R. C. King Jr, Physical Electronics, Inc., Minnesota, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- The number of Co atoms at the crystal surface was evaluated based on the X-ray analysis, assuming that each crystal has a perfect octahedral shape with uniform size

- Representatives of the reported best catalase-like activities are summarized in Table S3 in comparison with those of [1]Cl2 and [1](NO3)2

- Hashimoto Y., Yoshinari N., Kuwamura N., Konno T. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2015;88:1144–1146. [Google Scholar]

- Gas leak with overpressure can cause saturation of O2 evolution considering saturation at a similar level regardless of the different reaction rates and reusability of the catalyst. Partial cracking of crystals may also affect the reaction rate

- de Groot F. M. F. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 1994;67:529–622. [Google Scholar]

- Yamagami K., Fujiwara H., Imada S., Kadono T., Yamanaka K., Muro T., Tanaka A., Itai T., Yoshinari N., Konno T. and Sekiyama A., arXiv:1603.04590v1 [cond-mat.mtrl-sci], 2016.

- The ratio of CoII : CoII was calculated to be 11% : 89% by simulated fitting of PEY from CoII and CoIII standards to reproduce the XAS spectra

- Robinson J. M. Phys. Rep. 1979;51:1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Park S.-K., Kurshev V., Lee C. W., Levan L. Appl. Magn. Reson. 2000;19:21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kato S., Ueno T., Fukuzumi S., Watanabe Y. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:52376–52381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403532200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Frisch M. J., Trucks G. W., Schlegel H. B., Scuseria G. E., Robb M. A., Cheeseman J. R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Mennucci B., Petersson G. A., Nakatsuji H., Caricato M., Li X., Hratchian H. P., Izmaylov A. F., Bloino J., Zheng G., Sonnenberg J. L., Hada M., Ehara M., Toyota K., Fukuda R., Hasegawa J., Ishida M., Nakajima T., Honda Y., Kitao O., Nakai H., Vreven T., Montgomery Jr J. A., Peralta J. E., Ogliaro F., Bearpark M., Heyd J. J., Brothers E., Kudin K. N., Staroverov V. N., Kobayashi R., Normand J., Raghavachari K., Rendell A., Burant J. C., Iyengar S. S., Tomasi J., Cossi M., Rega N., Millam J. M., Klene M., Knox J. E., Cross J. B., Bakken V., Adamo C., Jaramillo J., Gomperts R., Stratmann R. E., Yazyev O., Austin A. J., Cammi R., Pomelli C., Ochterski J. W., Martin R. L., Morokuma K., Zakrzewski V. G., Voth G. A., Salvador P., Dannenberg J. J., Dapprich S., Daniels A. D., Farkas O., Foresman J. B., Ortiz J. V., Cioslowski J. and Fox D. J., Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2009.; (b) Grimme S. J. Comput. Chem. 2006;27:1787–1799. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Scalmani G., Frisch M. J. J. Chem. Phys. 2010;132:114110. doi: 10.1063/1.3359469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.