Abstract

Background

Intracranial pseudoaneurysm formation due to a ruptured non-traumatic aneurysm is extremely rare. We describe the radiological findings and management of pseudoaneurysms due to ruptured cerebral aneurysms in our case series and previously reported cases.

Patients and methods

Four additional and 20 reported patients presenting with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) are included. Radiological findings and clinical features of these patients were reviewed.

Results

In our series, three-dimensional computed tomographic angiography (3D-CTA) and/or angiography showed an irregular- or snowman-shaped cavity extending from the parent artery. The radiological examination additionally revealed delayed filling and retention of contrast medium. These findings were the same as previously reported cases. One patient underwent direct clipping of the true aneurysm. For the other three patients with aneurysms at the basilar and anterior communicating arteries, the true portion of the aneurysm was embolized with platinum coils. During the procedures, care was taken not to insert the coils into the distal pseudoaneurysm portion to prevent rupture. The review of 24 cases revealed that the location of the aneurysms was most frequent in the anterior communicating artery (41.7%), and 86.7% of patients were in a severe stage of SAH (>Grade 3 in WFNS or Hunt & Kosnik grading) implying abundant SAH.

Conclusions

Pseudoaneurysm formation in SAH after non-traumatic aneurysm rupture is rare. However, in cases with an irregular-shaped aneurysm cavity, pseudoaneurysm formation should be taken into consideration.

Keywords: Pseudoaneurysm, cerebral aneurysm, subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracerebral hematoma

Introduction

Pseudoaneurysms usually result from trauma, mycotic infection, vessel dissection, or congenital collagen deficiency.1–3 We previously reported a case of pseudoaneurysm in a thrombus located at the rupture site of a cerebral aneurysm for the first time.2 Since then, several reports describing pseudoaneurysm formation after aneurysmal rupture have been published.4–12 However, intracranial pseudoaneurysm formation due to a ruptured non-traumatic aneurysm is still rare, and remains to be clarified.3–12 Furthermore, pseudoaneurysms are difficult to manage and associated with a high risk of rupture during treatment. Recently, we encountered four additional cases of pseudoaneurysm formation at the rupture site of cerebral aneurysms. In this report, we present a case series and a review of the literature for reported cases of pseudoaneurysms formed after cerebral aneurysm rupture. We describe and review the clinical course, radiological findings, and management of this rare condition.

Case presentation

Four cases and 20 reported cases with ruptured aneurysms accompanied by pseudoaneurysms are summarized in Table 1. The mean patient age was 58.4 (range 28–87) years.

Table 1.

Summary of the cases with pseudoaneurysms.

| Case | Age (y.o.) | Sex | Location of aneurysm | Initial symptom | Grade (H&K) | Treatment | Treatment day | Size of an. (mm) | Modality | Radiological findings | Pathological findings | Outcome | Others | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 44 | F | Left ICA-AChA | IV | Coiling | 0 | 4 | Angiography | Rough wall | Good recovery | Coil migration Extravasation | 3 | ||

| 2 | 67 | F | Left ICA-PCoA | III | Coiling | 4 | 3 | Angiography | Rough wall CM retention | Death | Coil perforation Extravasation | 3 | ||

| 3 | 45 | M | AComA | II | Coiling (trial)→ clipping | 0 | 3 | 3D-CTA angiography | Lobular CM retention Incomplete filling of CM | Good recovery | Aneurysm thrombosis | 3 | ||

| 4 | 76 | F | Left ICA-PCoA | IV | Coiling | 1 | 4 | 3D-CTA angiography | Elongation Tapering Delayed filling of CM Irregular accessory cavity | Death | Perforation extravasation | 3 | ||

| 5 | 63 | M | AComA | IV | Coiling (partial) | 45 | 10 | 3D-CTA angiography | Lobular Delayed filling of CM | Vegetative state | 3 | |||

| 6 | 28 | M | Right MCA | I | Clipping | 0 | 3 | 3D-CTA angiography | Elongation CM retention Delayed filling of CM | Good recovery | 3 | |||

| 7 | 38 | F | Right ICA-PCoA | III | Clipping | 1 | 5 | Angiography | Dumbbell shape Incomplete filling of CM CM retention | Moderate disability | Right third nerve palsy | 3 | ||

| 8 | 50 | F | AComA | III | Clipping | 0 | 6 | 3D-CTA angiography | Elongation Tapering Delayed filling of CM Irregular accessory cavity | Good recovery | 3 | |||

| 9 | 42 | M | Left MCA | Headache | Clipping | 36 | 3D-CTA angiography | Irregular-shaped an. Snowman-like appearance Delayed opacification Delayed clearance of CM | Fibrin layer Hemosiderin deposition | Good recovery | Premature bleeding | 4 | ||

| 10 | 77 | F | Right MCA | Headache Vomiting | WFNS V | Clipping | 0 | 4 | 3D-CTA angiography | Irregular-shaped an. Heterogeneously opacified Delayed filling Partially remained CM | Vegetative state | 5 | ||

| 11 | 73 | F | Right A1/2 | Cons. loss | WFNS V | Clipping | 0 | 6 | 3D-CTA angiography | Irregular-shaped an. Late opacification Changing shape Retention of CM | Died on day 16 | Hypertension | 5 | |

| 12 | 63 | F | Left ICA (C2, blister an.) | Headache | IV | Coiling | 40 | Angiography | Stasis of CM | Moderate disability | Rerupture on Day 40 | 6 | ||

| 13 | 37 | M | AComA | Headache | Clipping | Angiography | Irregular | Blood clot enclosed with connective tissue | Good recovery | Rerupture during dissection | 7 | |||

| 14 | 55 | M | AComA | None → seizure Headache | Clipping | 1 | 3 × 2 | 3D-CTA angiography | Irregular-shaped an. Delayed filling Outpouching of CM | Good recovery | Family history of aneurysmal SAH | 8 | ||

| 15 | 52 | F | BA apex | Headache Cons. loss | Coiling | 0 | True: 4–5 | Angiography | Delayed and unequal filling Irregular stasis and delayed washout of CM | Good recovery | 9 | |||

| 16 | 61 | M | Left MCA | Speech dist. Cons. loss | IV | Clipping | 5 | 3D-CTA | Like a large an. | Thrombus destroyed an. wall | Died on day 10 | On warfarin | 10 | |

| 17 | 79 | F | AComA | Headache Cons. loss | IV | Coiling | 0 | Angiography | Irregular shape Delayed appearance Changing shape Unclear neck Retention of CM | Moderate disability | Embolization of the proximal true part | 11 | ||

| 18 | 87 | M | AComA | Headache Cons. loss | WFNS IV | Coiling | 2 | True: 3 Pseudo: 5 | Angiography | Delayed filling Changing shape Unclear neck Retention of CM | Died on day 9 | Embolization of the proximal true part | 12 | |

| 19 | 60 | M | AComA | Headache Cons. loss | WFNS V | Coiling | 9 | True: 2 Pseudo: 3 → 7 | Angiography | Irregular shape | mRS: 3 | Embolization of both true and false lumen | 12 | |

| 20 | 79 | F | AComA | Headache Cons. loss | WFNS IV | Coiling | 1 | True: 3 Pseudo: 7 | Angiography | Delayed appearance Changing shape Unclear neck Retention of CM | mRS: 3 | Embolization of the proximal true part | 12 | |

| Present case 1 | 56 | F | Left A2/3 | Cons. loss | 3 | Clipping | 0 | 9 × 6 × 5 | 3D-CTA | Distal: oval Proximal: thin cavity | Fresh thrombus without aneurysm wall | 3 | On warfarin | |

| Present case 2 | 53 | M | BA-SCA | Cons. loss | 5 | Coiling | 0 | True: 10 × 6 × 5 Pseudo: 20 × 5 × 5 | 3D-CT Aangiography | Irregular-shaped an. Delayed filling Retention of CM | NA | 6 | Hypertension | |

| Present case 3 | 43 | M | AComA | Cons. loss | 4 | Coiling | 0 | 2.7 × 2.2 × 2 | 3D-CTA | Irregular-shaped an. not detected on angiography | NA | 3 | Coil compaction → second coiling | |

| Present case 4 | 73 | F | BA tip | Cons. loss | 4 | Coiling | 0 | True: 6 × 4 × 3 Pseudo: 4.5 × 3.5 × 3 | Angiography | Delayed opacification Faint | NA | 5 | Four years ago: coil embolization |

an.: aneurysm; 3D-CTA: three dimensional-computed tomography angiography; AComA: anterior communicating artery; AChoA: anterior choroidal artery; BA: basilar artery; CM: contrast medium; cons: consciousness; F: female; H&K: Hunt and Kosnik; ICA: internal carotid artery; M: male; MCA: middle cerebral artery; mRS: modified Rankin Scale; NA: not applicable; PCoA: posterior communicating artery; SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage; SCA: superior cerebellar artery; y.o.: years old; WFNS: World Federation of Neurological Surgeons.

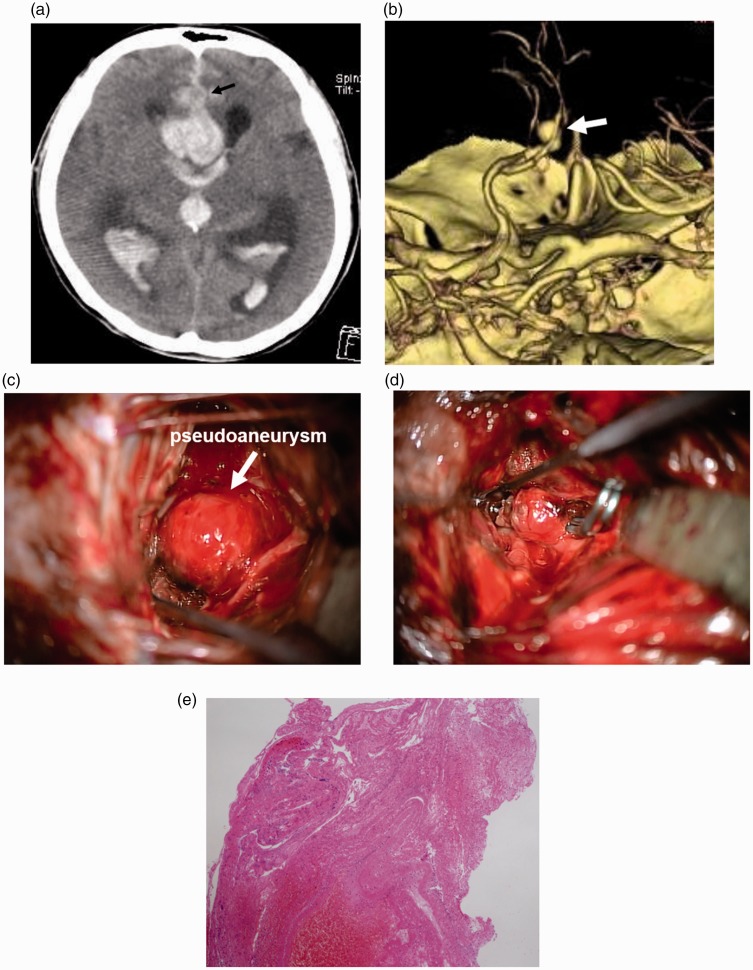

Case 1

A 56-year-old woman with a past history of multiple aneurysms in systemic arteries was found unconscious. She had been taking warfarin. Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), an intracerebral hematoma around the A2/3 portion of the anterior cerebral artery (ACA), and ventricular enlargement (Figure 1(a)). Three-dimensional CT angiography (3D-CTA) demonstrated an irregular-shaped aneurysm at the left A2/3 junction of the ACA (Figure 1(b)). The aneurysm configuration was composed of a distal oval portion and thin proximal cavity, and the inner surface was smooth on 3D-CTA. After the intravenous administration of menatetrenone and factor IX, an emergency craniotomy was performed. The aneurysm was exposed via the interhemispheric fissure. The round aneurysm was found. However, the wall of the aneurysm seemed to be very thin (Figure 1(c)), and different from that of a common aneurysm. During manipulation of the aneurysm, several points of the lesion ruptured and bled. The aneurysm wall was extremely prone to rupture. The lesion with thin wall was considered to be a pseudoaneurysm covered with connective tissue formed at the rupture point of a true aneurysm. Clipping of the pseudoaneurysm with multiple clips achieved transient hemostasis. Then, the pseudoaneurysm was carefully dissected from the surrounding tissue, and the neck of the true aneurysm was found at the junction of A2/3 behind the pseudoaneurysm. The aneurysm neck was clipped and complete hemostasis was achieved (Figure 1(d)). The portion thought to be the pseudoaneurysm dome was incised and subjected to pathological examination. The examination revealed that the specimen was consistent with a fresh thrombus without an aneurysm wall (Figure 1(e)). These findings indicated that the lesion observed on 3D-CTA was composed of a proximal true aneurysm and distal pseudoaneurysm formed at the rupture point of the aneurysm. The pseudoaneurysm portion was much larger than the true aneurysm. After clipping, an intra-arterial injection of fasudil hydrochloride for vasospasm and ventricle-peritoneal shunt for hydrocephalus were necessary. She was transferred to another hospital for rehabilitation on the 66th day.

Figure 1.

(a) CT demonstrating SAH and intracerebral hematoma around A2/3 of the ACA. An aneurysm is demonstrated as a low-density lesion (arrow). (b) 3D-CTA showing an irregular-shaped lesion at A2/3 (arrow). (c) Intra-operative photograph showing a round and thin-walled portion of the aneurysm. (d) The true aneurysm portion is clipped. (e) Microphotograph showing that the specimen is composed of a thrombus without a vascular wall. Hematoxylin and eosin, ×40.

CT: computed tomography; SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage; ACA: anterior cerebral artery; 3D-CTA: three-dimensional computed tomography angiography.

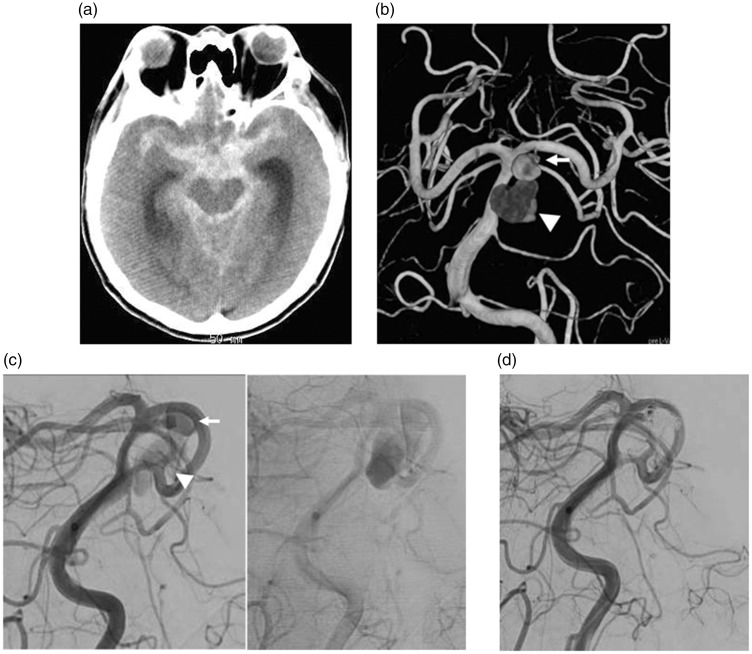

Case 2

A 53-year-old man with hypertension developed consciousness disturbance. CT on admission demonstrated SAH and ventricular enlargement (Figure 2(a)). 3D-CTA demonstrated an irregular-shaped aneurysm of the basilar artery (BA) at the bifurcation of the superior cerebellar artery (SCA) (Figure 2(b)). Endovascular treatment was performed immediately after the insertion of a ventriculo-external drainage tube. Angiography demonstrated a snowman-shaped aneurysm of the BA. Opacification of the distal side of the aneurysm was delayed and retention of the contrast medium (CM) was seen (Figure 2(c)). Therefore, the distal part of the aneurysm was considered as a pseudoaneurysm formed at the rupture point of the BA-SCA true aneurysm. The proximal portion of the aneurysm was embolized with a total of 12 platinum coils (Figure 2(d)). Postoperatively, he was treated with propofol to control the intracranial pressure; however, he died five days after embolization.

Figure 2.

CT demonstrating SAH (a), and 3D-CTA (b) showing a BA-SCA aneurysm (arrow) and a cavity (arrowhead) extending from the aneurysm. (c) The distal portion of the aneurysm showing delayed CM filling and washout on angiography. (d) Only the proximal portion of the aneurysm is embolized.

CT: computed tomography; SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage; 3D-CTA: three-dimensional computed tomography angiography; BA-SCA: basilar artery-superior cerebellar artery.

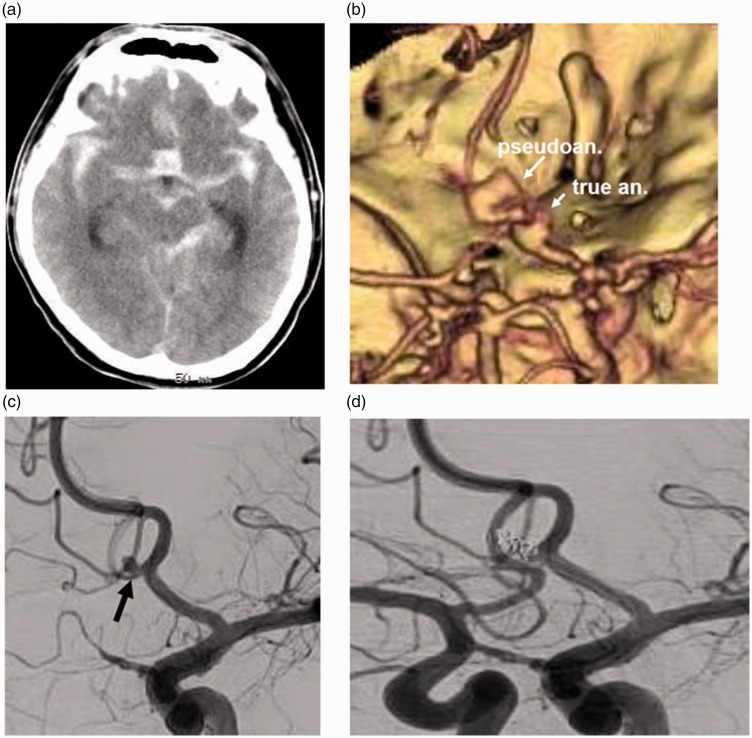

Case 3

A 43-year-old man without a significant past history was found unconscious. CT demonstrated diffuse SAH (Figure 3(a)). 3D-CTA demonstrated an irregular-shaped aneurysm at the portion of the anterior communicating artery (AComA) (Figure 3(b)). Angiography demonstrated an aneurysm at AComA (2.7 × 2.2 × 2 mm) (Figure 3(c)). The irregular-shaped aneurysm observed on 3D-CTA was diagnosed as a pseudoaneurysm formed at the rupture point of a true aneurysm, or the extravasation of CM. The aneurysm was embolized with four platinum coils. Several loops of the second coil protruded into the pseudoaneurysm cavity (Figure 3(d)). Twenty-seven days after onset, a right ventriculo-peritoneal shunt operation was performed. Sixty-three days after the first endovascular treatment, additional endovascular treatment was performed because of coil compaction. This may have been because the aneurysm with pseudoaneurysm had shrunk during the acute stage of aneurysm rupture. He was transferred to another hospital for rehabilitation with mild right hemiparesis 72 days after onset.

Figure 3.

(a) CT demonstrating SAH. (b) 3D-CTA demonstrating an irregular-shaped aneurysm cavity at AComA. (c) Angiography demonstrating an aneurysm at the AComA (arrow). However, an irregular-shaped additional cavity observed on 3D-CTA is not demonstrated. (d) The true aneurysm portion is embolized with platinum coils. A few loops of coils protrude outside the aneurysm.

CT: computed tomography; SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage; 3D-CTA: three-dimensional computed tomography angiography; AComA: anterior communicating artery.

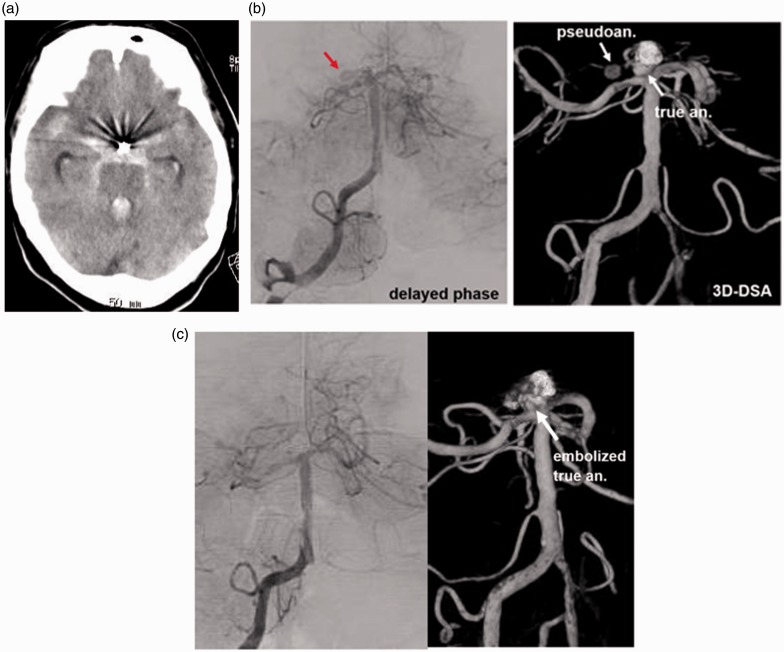

Case 4

A 73-year-old woman was found unconscious. She had suffered from SAH four years ago, and a ruptured BA tip aneurysm had been embolized in another hospital. CT on admission revealed SAH with ventricular rupture and hydrocephalus (Figure 4(a)). Emergency angiography demonstrated a partially embolized aneurysm at the BA tip. After embolization of the anterior part of the aneurysm, the posterior protrusion (4.5 × 3.5 × 3 mm) was still opacified with CM. Continuing from the posterior portion of the aneurysm, a cavity with delayed opacification and retention of CM was observed protruding to the right (Figure 4(b)). This portion was considered as a pseudoaneurysm formed in the thick SAH. The portion of the true aneurysm was embolized with seven platinum coils. After embolization, the pseudoaneurysm portion was not opacified (Figure 4(c)). During the procedures, only the true portion was embolized, and care was taken not to insert the coils into the pseudoaneurysm portion.

Figure 4.

(a) CT showing SAH. (b) Angiography demonstrating a cavity protruding to the right from the recurrent BA tip aneurysm. Angiography showing delayed filling and washout of CM in the additional cavity. (c) Post-embolization angiography demonstrating complete obliteration of the aneurysm and disappearance of the pseudoaneurysm.

CT: computed tomography; SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage; CM: contrast medium.

Discussion

Pseudoaneurysm formation at the rupture site of a non-traumatic cerebral aneurysm is extremely rare.3,4 A pseudoaneurysm is formed in a blood clot adhering to the rupture point. There are several reports describing cerebral pseudoaneurysms.3–12

Recently, we encountered four additional patients with pseudoaneurysms. One patient with an A2/3 aneurysm (Case 1) was treated by direct clipping, and three other cases (Cases 2–3) with BA and AComA aneurysms were treated with an endovascular technique. For Case 1, preoperative 3D-CTA clearly showed a round lesion with a proximal stem-like portion. The small proximal portion continued from the parent artery, and the initial diagnosis was a large aneurysm. In this case, preoperative 3D-CTA showed features of a pseudoaneurysm. For the other three cases with pseudoaneurysms, endovascular treatment was performed. In Case 2, the pseudoaneurysm was observed on both 3D-CTA and angiography. In Case 3, the pseudoaneurysm was observed on preoperative 3D-CTA, but not on angiography. The pseudoaneurysm cavity continued from the AComA true aneurysm. This pseudoaneurysm cavity might be a space formed in a thick SAH. In the fourth case with a previously embolized aneurysm, a pseudoaneurysm was detected on angiography. In Cases 2 and 4, opacification of pseudoaneurysms were faint on angiography. As mentioned above, a pseudoaneurysm can be detected with both 3D-CTA and angiography. However, it cannot always be detected with both modalities at the same time. These variations might be due to differences in the timing of examinations, intracranial pressure, and injection power of the CM.

We initially reported that the radiological findings of the pseudoaneurysms were irregular aneurysm wall, delayed opacification of the lesion, and delayed washout and retention of the CM.3 Ide et al.4 reported a pseudoaneurysm case with a snowman-like appearance. Mori et al.5 additionally reported radiological characteristics such as delayed appearance, late opacification, changing shape, and retention of the CM after venous phase. They proposed calling the aneurysm with pseudoaneurysm a “ghost aneurysm.” Other reports described similar radiological findings, unequal filling or outpouching of the CM, and unclear neck6–12 as shown in Table 1. These radiological features are identical to those of traumatic pseudoaneusyms.1,2 Even though the etiology is different, a pseudoaneurysm is composed without a vascular wall. A pseudoaneurysm due to a ruptured cerebral aneurysm is located in the thrombus. Therefore, the pseudoaneurysm wall is very weak and prone to rupture during manipulation. Special care of the pseudoaneurysm portion is necessary during operation procedures.

The pseudoaneurysm at the tip of the true aneurysm was formed in the thick SAH or intracerebral hematoma. Mori et al.5 described that an extraluminal hematoma may recanalize or remain in communication with the true aneurysm arising from the parent artery. Therefore, for pseudoaneurysm formation, thick hematoma around the aneurysm is necessary. D’Urso et al.8 reported a case of AComA aneurysm, in which a pseudoaneurysm newly developed after the second bleeding. Initial SAH around the AComA aneurysm was thin. The second rupture resulted in a sufficient amount of SAH for a pseudoaneurysm to be formed. In fact, in cases of aneurysms accompanied by pseudoaneurysms, SAH was thick, including a pseudoaneurysm cavity in the hematoma. Therefore, most of the cases with pseudoaneurysms were in a severe state with abundant SAH. Our four cases were graded 3–5 on the Hunt and Kosnik (H&K) scale of SAH grading. And in a previous 11 cases with detailed description, nine were graded more than 3 of H&K or World Federation of Neurological Surgeons (WFNS) grading. In cases with thick hematoma, if the aneurysm possesses an unusual radiological countenance, pseudoaneurysm formation should be taken into consideration. For cases with pseudoaneurysms, accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment are mandatory.

As for location of the aneurysm with pseudoaneurysm, 41.7% of the lesions were located at the AComA, followed by 16.6% each of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) and the internal carotid artery (ICA). Incidence of pseudoaneurysm occurring in the AComA is almost twice the distribution of common AComA aneurysms. In cases with AComA aneurysms, thick hematoma may be formed around the aneurysm in the interhemispheric fissure. Interhemispheric fissure is usually tight compared to Sylvian fissure and carotid cistern. Atrophic change around the AComA is usually less than that of the superficial brain. And further, the parent arteries are complex. Around an AComA aneurysm, there are at least four normal arteries. These anatomical features may contribute to form localized thick hematoma around the AComA and further pseudoaneurysm.

Concerning treatment for an aneurysm with a pseudoaneurysm, among 24 cases including ours, 11 cases were treated by direct clipping and the 13 other cases underwent endovascular treatment. Advancement of endovascular technique enabled us to treat cerebral aneurysms with pseudoaneurysms safely. Reports describing the usefulness of endovascular embolization have been published.9,11,12 In these reports, only the true portion of the aneurysm was embolized with platinum coils in most cases. In one case reported by Ito et al.,12 both true and pseudoaneurysm were embolized on day 9. The authors described that fibrosis might occur around the pseudoaneurysm in the nine days after onset, and possibility of rupture during procedure might decrease. Our three patients underwent endovascular embolization on day 0, and the true aneurysm was embolized, which resulted in the successful disappearance of the lesions. For direct surgery, if the aneurysm neck is easily recognized before manipulating the pseudoaneurysm portion, direct clipping might be performed safely as in Case 16.10 However, if the pseudoaneurysm portion is shallow in the operative field, observation of the true portion behind the large pseudoaneurysm is difficult. As in Case 1 of our series, the pseudoaneurysm portion is very fragile and easy to bleed. Manipulation of the pseudoaneurysm before exposure of the true aneurysm neck resulted in intraoperative hemorrhage. For such a case, direct clipping might not be easy, and endovascular embolization may be a suitable treatment. Or an operative approach to be able to expose the true aneurysm prior to the pseudoaneurysm portion should be selected.

Conclusion

Pseudoaneurysm formation after rupture of an intracranial aneurysm is rare. However, in a case with an irregular-shaped aneurysm cavity, pseudoaneurysm formation should be taken into consideration.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions include the following: Motohiro Nomura: study conception and design, drafting of manuscript, critical revision, treatment of patient; Kentaro Mori: drafting of manuscript, critical revision; Akira Tamase: drafting of manuscript, critical revision; Tomoya Kamide: drafting of manuscript, critical revision, treatment of patient; Shunsuke Seki: drafting of manuscript, critical revision, treatment of patient; Yu Iida: drafting of manuscript, critical revision; Yuichi Kawabata: drafting of manuscript, critical revision; Tatsu Nakano: drafting of manuscript, critical revision; Taro Kitabatake: radiological examination, drafting of manuscript, critical revision; Teruyuki Nakajima: radiological examination, drafting of manuscript, critical revision; Kiyoyuki Yasutake: radiological examination, drafting of manuscript, critical revision; Kei Egami: radiological examination, drafting of manuscript, critical revision; Tatsunori Takahashi: radiological examination, drafting of manuscript, critical revision; Mitsuyuki Takahashi: radiological examination, drafting of manuscript, critical revision; and Kunio Yanagimoto: pathological examination, drafting of manuscript, critical revision.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Lampert TE, Halbach VV, Higashida RT, et al. Endovascular treatment of pseudoaneurysms with electrolytically detachable coils. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998; 19: 907–911. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teitelbaum GP, Dowd CF, Larsen DW, et al. Endovascular management of biopsy-related posterior inferior cerebellar artery pseudoaneurysm. Surg Neurol 1995; 43: 357–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nomura M, Kida S, Uchiyama N, et al. Ruptured irregular shaped aneurysm: Pseudoaneurysm formation in a thrombus located at the rupture site. J Neurosurg 2000; 93: 998–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ide M, Kobayashi T, Tamano Y, et al. Pseudoaneurysm formation at the rupture site of a middle cerebral artery aneurysm. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2003; 43: 443–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mori K, Kasuya C, Nakao Y, et al. Intracranial pseudoaneurysm due to rupture of a saccular aneurysm mimicking a large partially thrombosed aneurysm (“ghost aneurysm”): Radiological findings and therapeutic implications in two cases. Neurosurg Rev 2004; 27: 289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanoue S, Kiyosue H, Matsumoto S, et al. Ruptured “blisterlike” aneurysm with a pseudoaneurysm formation requiring delayed intervention with endovascular coil embolization. J Neurosurg 2004; 101: 159–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding H, You C, Yin H. Nontraumatic and noninfectious pseudoaneurysms on the circle of Willis: 2 Case reports and review of the literature. Surg Neurol 2008; 69: 414–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Urso P, Loumiotis I, Milligan BD, et al. “Real time” angiographic evidence of “pseudoaneurysm” formation after aneurysm rebleeding. Neurocrit Care 2011; 14: 459–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yanamadala V, Lin N, Zarzour H, et al. Endovascular coiling of a ruptured basilar apex aneurysm with associated pseudoaneurysm. J Clin Neurosci 2014; 21: 1637–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nomura M, Tamase A, Kamide T, et al. Pseudoaneurysm formation in intracerebral hematoma due to ruptured middle cerebral artery aneurysm. Surg J 2015; 1: e47–e49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito H, Morishima H, Onodera H, et al. Acute phase endovascular intervention on a pseudoaneurysm formed due to rupture of an anterior communicating artery aneurysm. J Neurointervent Surg 2015; 7: e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito H, Sase T, Uchida M, et al. Coil embolization of a ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm forming a pseudoaneurysm: Report of three cases [in Japanese]. No Shinkei Geka 2016; 44: 323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]