Abstract

Acute necrotizing encephalopathy is characterized by multiple, symmetrical lesions involving the thalamus, brainstem, cerebellum, and white matter and develops secondarily to viral infections. Influenza viruses are the most common etiological agents. Here, we present the first case of acute necrotizing encephalopathy to develop secondarily to human bocavirus.

A 3-year-old girl presented with fever and altered mental status. She had had a fever, cough, and rhinorrhea for five days. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit with an initial diagnosis of encephalitis when vomiting, convulsions, and loss of consciousness developed. Signs of meningeal irritation were detected upon physical examination. There was a mild increase in proteins, but no cells, in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Brain magnetic resonance imaging showed symmetrical, heterogeneous hyperintensities bilaterally in the caudate nuclei and putamen. Ammonium, lactate, tandem mass spectroscopy, and urine organic acid were normal. No bacteria were detected in the CSF cultures. Human bocavirus was detected in a nasopharyngeal aspirate using real-time PCR, while no influenza was detected. Oseltamivir, acyclovir, 3% hypertonic saline solution, and supportive care were used to treat the patient, who was discharged after two weeks. She began to walk and talk after one month of physical therapy and complete recovery was observed after six months.

Human bocavirus is a recently identified virus that is mainly reported as a causative agent in respiratory tract infections. Here, we present a case of influenza-like acute necrotizing encephalopathy secondary to human bocavirus infection.

Keywords: Acute necrotizing encephalopathy, basal ganglion, human bocavirus, child

Introduction

Mizuguchi et al. first described acute necrotizing encephalopathy (ANE) in 1995; it is characterized by altered mental status, seizures, and coma preceded by a viral upper respiratory tract infection, with multiple, symmetrical brain lesions involving the thalamus, brainstem, tegmentum, and cerebral white matter.1 Influenza infection is the most common preceding event of ANE.2 Here, we present a pediatric patient who developed ANE after a respiratory tract infection caused by human bocavirus (HBoV).

Case report

An otherwise healthy 3-year-old girl presented to our hospital with fever, altered mental status and right-sided focal seizure activity. She had a five-day history of fever with rhinorrhea and cough and the more recent development of lethargy, nausea, vomiting and ataxia. There was no past medical history of neurological problems such as seizure activity or an immunodeficiency condition. On physical examination, the patient was unconscious and undergoing a right focal convulsion. The muscle tone was increased and more prominent on the right side. She had nuchal rigidity and positive Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs. Muscle strength and the deep tendon reflexes were normal. She had no papillary edema. The serum sodium, glucose, hepatic enzymes, complete blood count, procalcitonin level, and C-reactive protein were normal. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed slightly increased protein (48 mg/l) and normal glucose (61 mg/l) levels, without pleocytosis. Gram staining and cultures of the CSF, blood, and urine were negative. The serum ammonium level and other metabolic tests were normal. Electroencephalography (EEG) showed intermittent, isolated spikes with slow wave discharge with underlying activity in the left hemisphere. Antiepileptic therapy was given. Contrast-enhanced cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed heterogeneous involvement of the bilateral caudate nuclei and putamen, which was more prominent on the left side (Figures 1–3). Based on these findings, ANE was diagnosed. Follow-up MRI on day 14 showed progression of the basal ganglion lesions. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of a nasopharyngeal aspirate was positive for HBoV and negative for influenza. Intravenous immunoglobulin was started at a dose of 0.4 g/kg for five days. Baclofen and L-DOPA were prescribed for one month because the patient had a hand tremor and marked rigidity. The patient was referred to physical therapy. At the end of three months, the patient was awake, reactive, and could talk spontaneously and play with her friends. She had no difficulty feeding. Follow-up MRI obtained at six months showed near-complete resolution of the lesions.

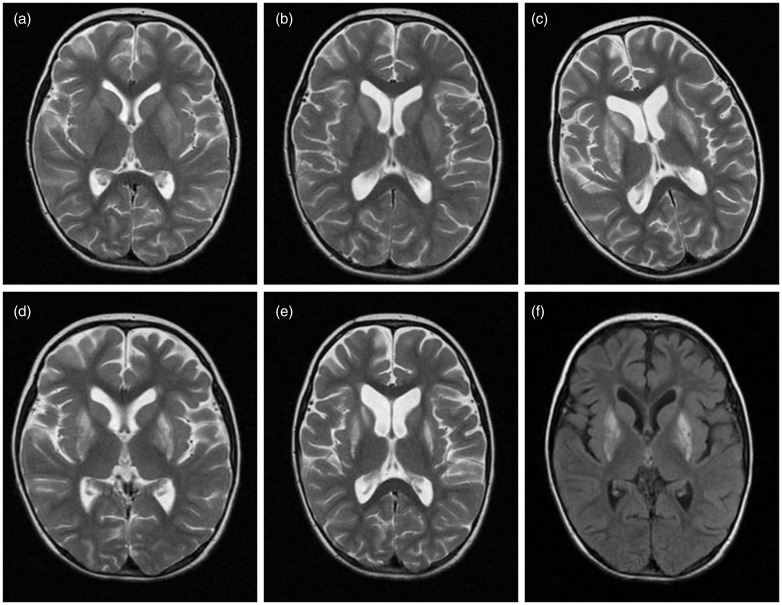

Figure 1.

Symmetrical, heterogeneous, hyperintense signal changes in the caudate nuclei and putamen on T2-weighted axial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) obtained at baseline ((a), (b)), 14 days (c), and one month ((d), (e)), and on axial flair MRI obtained at one month (f).

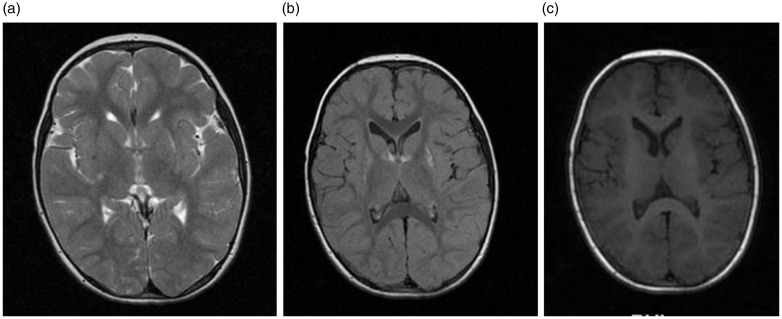

Figure 2.

Marked regression and resolution of the lesions in the caudate nuclei and putamen on T2-weighted axial ((a), (b)) and flair (c) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) obtained six months after treatment.

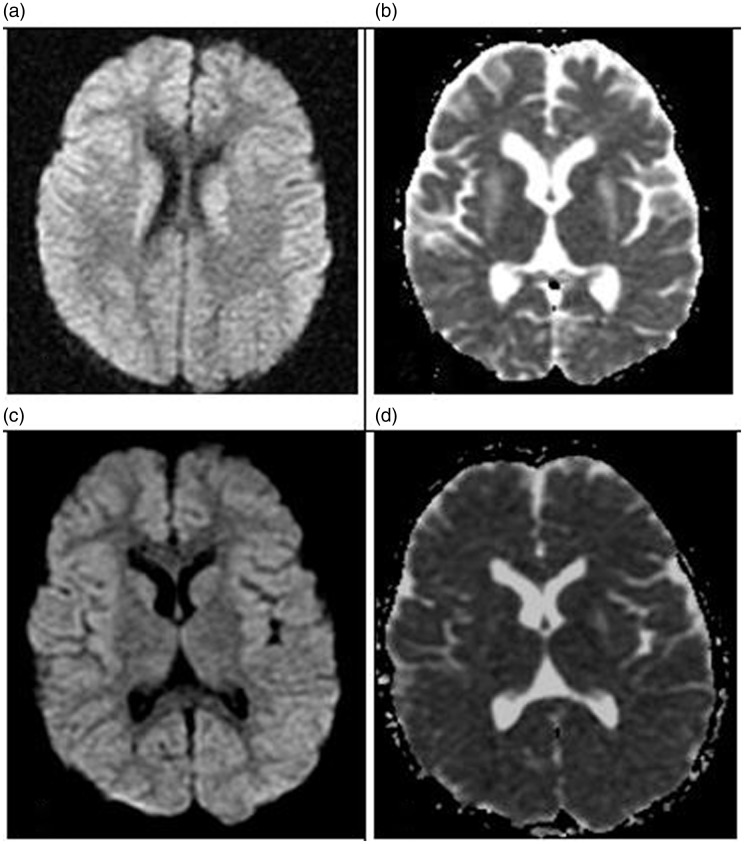

Figure 3.

Diffusion restriction in the caudate nuclei and putamen was seen on diffusion-weighted imaging-apparent diffusion coefficient magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) ((a), (b)) as was marked regression and resolution of the lesions after treatment ((c), (d)).

Discussion

Here, we described a possible association between HBoV and ANE in a pediatric patient. Mizuguchi et al. proposed the following diagnostic criteria for ANE: (a) acute encephalopathy following a viral febrile disease with rapid deterioration in consciousness or convulsions; (b) increased protein in the CSF without CSF pleocytosis; (c) neuroimaging findings of multiple, symmetric brain lesions involving the bilateral thalami, brainstem, periventricular white matter, internal capsule, putamen, and cerebellum; (d) elevated serum aminotransferases to varying degrees, but no hyperammonemia, and hypoglycemia; and (e) the exclusion of similar diseases.1

Our case met these criteria, with the exception of elevated serum aminotransferases. Multiple, symmetrical brain lesions in both thalami are the most prominent feature of ANE. In our patient, there were no thalamic lesions, but she had lesions in the bilateral caudate nuclei and putamen that were more prominent on the left side. ANE can rarely involve the cerebral white matter, internal capsule, basal ganglion, putamen, brainstem, and cerebellum.3

Influenza A (H1N1) is the most commonly associated virus of ANE.2 Encephalitis caused by human HboV has also been reported,4,5 although HboV has not been reported as causing ANE. Our patient had MRI findings consistent with those described in ANE, and no influenza A virus was isolated from the upper respiratory tract, while HboV was positive in the nasal specimen. The patient presented with findings of encephalitis following a viral upper respiratory tract infection. HboV was detected in a nasal specimen using a real-time PCR method. She had no pre-existing neurological or metabolic disease. No other cause of encephalopathy was found after a thorough investigation. For these reasons, we believe the ANE was related to HboV in our patient.

In summary, although ANE is often linked to influenza, it may develop secondarily to HboV, a recently identified respiratory tract pathogen.

Acknowledgments

The English in this document has been checked by at least two professional editors, both native speakers of English. For a certificate, please see: http://www.textcheck.com/certificate/29Ucs0.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Mizuguchi M, Abe J, Mikkaichi K, et al. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy of childhood: A new syndrome presenting with multifocal, symmetric brain lesions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1995; 58: 555–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surana P, Tang S, McDougall M, et al. Neurological complications of pandemic influenza A H1N1 2009 infection: European case series and review. Eur J Pediatr 2011; 170: 1007–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoganathan S, Sudhakar SV, James EJ, et al. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy in a child with H1N1 influenza infection: A clinicoradiological diagnosis and follow-up. BMJ Case Rep 2016; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mori D, Ranawaka U, Yamada K, et al. Human bocavirus in patients with encephalitis, Sri Lanka, 2009–2010. Emerg Infect Dis 2013; 19: 1859–1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akturk H, Sık G, Salman N, et al. Atypical presentation of human bocavirus: Severe respiratory tract infection complicated with encephalopathy. J Med Virol 2015; 87: 1831–1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]