Abstract

Introduction

Some of the latest groundbreaking trials suggest that noncontrast cranial computed tomography and computed tomography-angiography are sufficient tools for patient selection within six hours of symptom onset. Before endovascular stroke therapy became the standard of care, patient selection was one of the most useful tools to avoid futile reperfusions. We report the outcomes of endovascularly treated stroke patients selected with a perfusion-based paradigm and discuss the implications in the current era of endovascular treatment.

Material and methods

After an interdisciplinary meeting in September 2012 we agreed to select thrombectomy candidates primarily based on computed tomography perfusion with a cerebral blood volume Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Scale (CBV-ASPECTS) of <7 being a strong indicator of futile reperfusion. In this study, we retrospectively screened all patients with an M1 thrombosis in our neurointerventional database between September 2012 and December 2014.

Results

In 39 patients with a mean age of 69 years and a median admission National Institute of Health Stroke Scale of 17 the successful reperfusion rate was 74% and the favourable outcome rate at 90 days was 56%. Compared to previously published data from our database 2007–2011, we found that a two-point increase in median CBV-ASPECTS was associated with a significant increase in favourable outcomes.

Conclusion

Computed tomography perfusion imaging as an additional selection criterion significantly increased the rate of favourable clinical outcome in patients treated with mechanical thrombectomy. Although computed tomography perfusion has lost impact within the six-hour period, we still use it in cases beyond six hours as a means to broaden the therapeutic window.

Keywords: CBV-ASPECTS, mechanical thrombectomy, reperfusion, stroke time-window, penumbra

Introduction

Mechanical thrombectomy has been a therapeutic option in the treatment of stroke patients for more than two decades. After several years of technical improvements and advances in the imaging of acute ischaemic stroke, several randomised trials have justified the superiority of endovascular therapy compared to standalone treatment with intravenous (i.v.) thrombolysis.1,2 During the ongoing developments in the field of endovascular stroke therapy, several generations of revascularisation devices have been introduced so far and reperfusion rates have been herewith significantly improved over time.3–6 In addition to technical changes, several different imaging strategies have been utilised to select patients for the endovascular approach and, even in the post-evidence era, there is no clear consensus on the most advantageous patient selection algorithm. One of the imaging strategies that has been used in some of the recently published trials is computed tomography perfusion (CTP),2,7 mainly due to its sensitivity in the detection of large ischaemic cores. Both studies used an automated software analysis of the CTP datasets. In another trial published in 2015 a multi-phase computed tomography (CT)-angiography was used as a surrogate CTP to assess collaterals.8 Other studies have found that the analysis of cerebral blood volume (CBV) images with the Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Scale (ASPECTS) has a better positive and negative predictive value regarding clinical outcome compared to noncontrast CT or CT-angiography scores.9,10 In contrast, other trials like the Multi Center Randomized Clinical trial of Endovascular Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke in the Netherlands (MR CLEAN) used only noncontrast CT and CT-angiography images to select patients for endovascular stroke therapy, thereby proving the benefit of endovascular stroke therapy, albeit being less selective.1 Remarkably, it was not until publication of the MR CLEAN results in 20151 that endovascular stroke therapy was established as the standard of care for acute stroke with underlying large artery occlusion. Therefore, we and others7 have been deploying rather strict selection criteria for patient treatment, including the analysis of CBV. The aim of this study is to retrospectively show how CTP image-based selection has indeed improved the rate of favourable outcome in our department and to discuss its potential role in the imaging strategy of acute ischaemic stroke in the future.

Material and methods

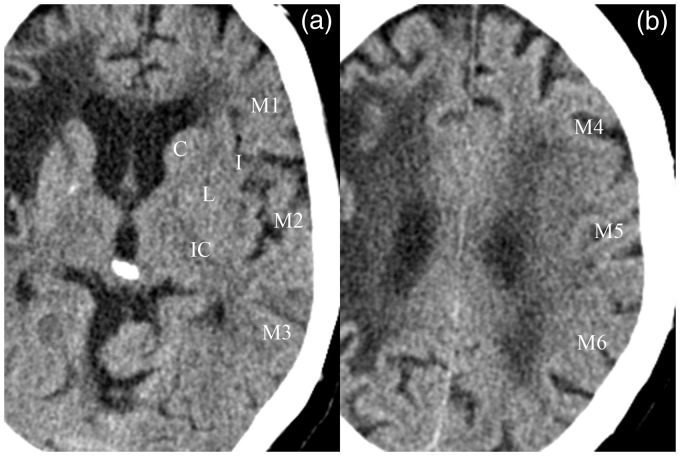

The publication of the MR CLEAN study results in 20151 has established endovascular stroke therapy as the standard of care for acute stroke with underlying large artery occlusion. MR CLEAN suggests noncontrast CT and CT-angiography images as mainstream selection criteria of endovascular thrombectomy candidates. In the pre-evidence era, after an interdisciplinary meeting in September 2012 we decided to select thrombectomy candidates amongst stroke patients primarily based on CTP, with a CBV-ASPECTS of <7 being a strong indicator of futile reperfusion.11 All patients with an M1 thrombosis of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) treated between September 2012 and December 2014 were included in this study. Patient data, neuroradiological scores and clinical outcomes were extracted from our prospectively assessed university hospital stroke database. All stroke patients with a large artery occlusion were assessed at admission, discharge and follow-up (90 days after symptom onset) by a certified stroke neurologist (more than five years of experience). Neuroradiological scores were evaluated by a neuroradiology resident with more than three years of experience and validated by a neuroradiology senior with more than 10 years of experience. All patients underwent multimodal CT workup consisting of noncontrast CT, CTP and CT-angiography on a 128-slice multidetector CT scanner (Siemens Definition AS+, Siemens Healthcare Sector, Forchheim, Germany). CTP consisted of 30 near whole-brain spiral scans (96 mm coverage of the z-axis, 2 s delay after start of contrast agent injection, 45 s total acquisition time, 80 kV, 200 mAs and effective dose of ∼5 mSv). Contrast agent was injected at a rate of 6 ml/s for 6 s followed by 30 ml of saline chaser. Renal function was not tested prior to multimodal stroke workup in order to save time and promote fast endovascular treatment. However, serum creatinine levels were analysed and glomerular filtration was calculated after thrombectomy in order to monitor renal function and treat possible dysfunction. CTP data were reconstructed with a slice thickness of 5 mm every 3 mm (H20f Kernel, 512 matrix) and analysed by a neuroradiologist using a commercial analysis package (Volume Perfusion CT Neuro; Siemens) with a delay-invariant deconvolution method, automatic motion correction and a dedicated noise reduction technique for dynamic data. Patients eligible for intravenous thrombolytic therapy received 0.9 mg/kg of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (i.v. rtPA) directly after noncontrast CT. Detection of large artery occlusion led to further analysis of CBV data with the ASPECTS, a 10-point scale for the assessment of early ischaemic changes of the MCA territory (Figure 1). Every MCA region with early ischaemic changes leads to a subtraction of one point from 10, resulting in an ASPECTS of zero for a complete MCA infarction and an ASPECTS of 10 for a regular CT. After interdisciplinary discussion and decision, patients were transferred to the angiography suite and treated with mechanical thrombectomy, either with distal aspiration or with a combination of distal aspiration and stent retrieval. A post-interventional flat-panel CT was acquired in order to exclude angiographic subtle complications such as contrast extravasation or haemorrhage. A follow-up CT was acquired with the aforementioned multidetector CT scanner, either after 24 h or upon clinical deterioration.

Figure 1.

Noncontrast computed tomography images of a 79-year-old patient delineating the 10 areas of the Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Scale (ASPECTS). (a) shows the seven regions of the ganglionic while (b) the three regions of the supraganglionic level on the left side. One point is subtracted from 10 for signs of early ischemia in each of the 10 ASPECTS regions. An older cerebral infarction is depicted in the right middle cerebral artery territory.

Statistical analysis was conducted with the MedCalc statistical package (MedCalc v14, Ostend, Belgium). Clinical and neuroradiological parameters were compared between patients with favourable [modified Rankin Scale (mRS) ≤2] and poor (mRS >2) 90 day clinical outcome. Continuous parameters were compared either with the Welch t-test in cases of normal distribution or with the Mann-Whitney U-test in cases of non-normal or ordinal distribution. Categorical variables were compared between the two groups by Fischer exact test. Selected variables were further examined by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis and optimal criterion values were calculated. Additionally, we calculated the probability of favourable outcome at follow-up by stepwise logistic regression using all variables that were significantly different between groups in the univariate analysis.

Results

Thirty-nine consecutive patients with an M1 occlusion were treated in our stroke centre between September 2012 and December 2014 and included in this study. Median age was 72 [interquartile range (IQR) 61–77, range 40–81], 16/39 (41%) were female. The admission median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) was 17 (IQR 13–21) and the median mRS was 5 (IQR 4–5). Eighty percent of the patients showed a dense media sign with a mean length of 14 mm (SD ± 7). Eighteen patients were treated with a combination of i.v. rtPA, intraarterial (i.a.) rtPA and mechanical thrombectomy; 12 patients received i.v. rtPA and mechanical thrombectomy; seven patients were ineligible for i.v. lysis and received only mechanical thrombectomy while two patients were treated with a combination of i.a. rtPA and mechanical thrombectomy. After treatment we found a median discharge NIHSS of 6 (IQR 2–13) and a median discharge mRS of 3 (IQR 2–4). Imaging parameters were significantly different between patients with favourable and patients with poor clinical outcome, as shown in Table 1, while medical comorbidities did not differ between the two groups. A newly published outcome predictor scale (GSS), combining CBV-ASPECTS, age and admission NIHSS, was significantly different between patients with favourable and poor outcome. A sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 65% were found for CT-ASPECTS with an optimal criterion value of >6 (area under the curve 0.795, P < 0.001). A sensitivity of 73% and a specificity of 65% were found for CBV-ASPECTS with an optimal criterion value of >8 (area under the curve 0.765, P < 0.001). A sensitivity of 45% and a specificity of 82% were found for CTA-ASPECTS with an optimal criterion value of >8 (area under the curve 0.713, P = 0.008). Eighty-seven percent of the patients presented with an angiographic thrombolysis in cerebral infarction (TICI) score of zero, while 13% had a TICI of one on initial digital subtraction angiography. We documented a successful reperfusion [modified TICI score (mTICI) ≥ 2b] in 74% of the cases. Successful reperfusion was associated with better outcomes (P = 0.071). Lateralization was not associated with better outcomes as 57% of the patients with a right-sided and 56% of the patients with a left-sided thrombus presented with a favourable neurological outcome after 90 days (P = 1). Pre-interventional administration of i.v. rtPA was also not associated with better outcomes (P = 0.141). There was a trend for worse clinical outcomes with general anaesthesia (P = 0.093) as 46% of the patients showed favourable outcome after thrombectomy with general anaesthesia versus 77% of the patients without general anaesthesia. Symptomatic intracranial haemorrhages were sparse with only one documented case (2.6%). In seven patients (18%) we documented an intracranial haemorrhage until discharge; amongst them we observed one case of type-1 haemorrhagic transformation, five patients with a type-2 haemorrhagic transformation and another with a type-1 parenchymal haematoma. A mortality of 18% was documented after 90 days. In the stepwise logistic regression, age [P = 0.007, odds ratio (OR) 0.84, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.75–0.96] and CBV-ASPECTS (P = 0.010, OR 4.10, 95% CI 1.39–12.14) were significant predictors of the outcome (Figure 2), both independent of the time from symptom onset.

Table 1.

Baseline and imaging characteristics, treatment times and clinical outcome between patients with favourable and poor outcome at follow-up.

| Total (n = 39) | Follow-up mRS ≤ 2 (n = 22, 56%) | Follow-up mRS > 2 (n = 17, 44%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 72 (61–77) | 66 (60–72) | 77 (73–79) | 0.001a |

| Admission NIHSS, median (IQR) | 17 (13–21) | 16 (8–19) | 19 (13–22) | 0.129 |

| Admission mRS, median (IQR) | 5 (4–5) | 4 (4–5) | 5 (4–5) | 0.059 |

| Discharge NIHSS, median (IQR) | 6 (2–14) | 3 (1–6) | 18 (11–25) | <0.0001 |

| Discharge mRS, median (IQR) | 3 (2–4) | 2 (1–2) | 5 (4–6) | <0.0001 |

| Medical comorbidities | ||||

| Hyperlipidaemia | 22 (56%) | 12 (55%) | 10 (59%) | 1 |

| Hypertension | 30 (77%) | 16 (73%) | 14 (82%) | 0.704 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 (21%) | 3 (14%) | 5 (29%) | 0.261 |

| Smoking | 15 (39%) | 11 (50%) | 4 (24%) | 0.111 |

| PAD | 2 (5%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (6%) | 1 |

| Obesity | 13 (34%) | 6 (29%) | 7 (41%) | 0.501 |

| Imaging scores, median (IQR) | ||||

| CT-ASPECTS | 9 (8–10) | 9 (8–10) | 8 (7–9) | 0.004a |

| CTA-ASPECTS | 8 (7–9) | 8 (8–9) | 8 (6–8) | 0.021a |

| CBV-ASPECTS | 8 (8–9) | 8 (7–9) | 6 (5–8) | 0.001a |

| CBF-ASPECTS | 4 (3–5) | 5 (3–6) | 3 (2–4) | 0.004a |

| TTD-ASPECTS | 2 (1–4) | 3 (1–5) | 1 (1–2) | 0.023a |

| MTT-ASPECTS | 3 (2–5) | 4 (2–5) | 2 (1–3) | 0.013a |

| Δ(CBV-CBF) ASPECTS | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–5) | 0.818 |

| Δ(CBV-TTD) ASPECTS | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) | 5 (3–5) | 0.229 |

| Δ(CBV-MTT) ASPECTS | 4 (3–5) | 4.5 (4–5) | 4 (3–5) | 0.208 |

| GSS | 0 (−2–2) | 1 (0–3) | −2 (−3–0) | 0.001a |

| Timeline | ||||

| Onset to mTICI ≥ 2b, mean (SD) | 206 (±78) | 188 (±75) | 241 (±73) | 0.078 |

| Groin to mTICI ≥ 2b, mean (SD) | 51 (±32) | 51 (±35) | 50 (±28) | 0.980 |

mRS: modified Rankin scale; SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health stroke scale; PAD: peripheral artery disease; ASPECTS: Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Scale; CT: computed tomography; CTA: CT angiography; CBV: cerebral blood volume; CBF: cerebral blood flow; TTD: time to drain; MTT: mean transit time; GSS: Goettinger stroke scale; mTICI: modified thrombolysis in cerebral infarction.

P < 0.05.

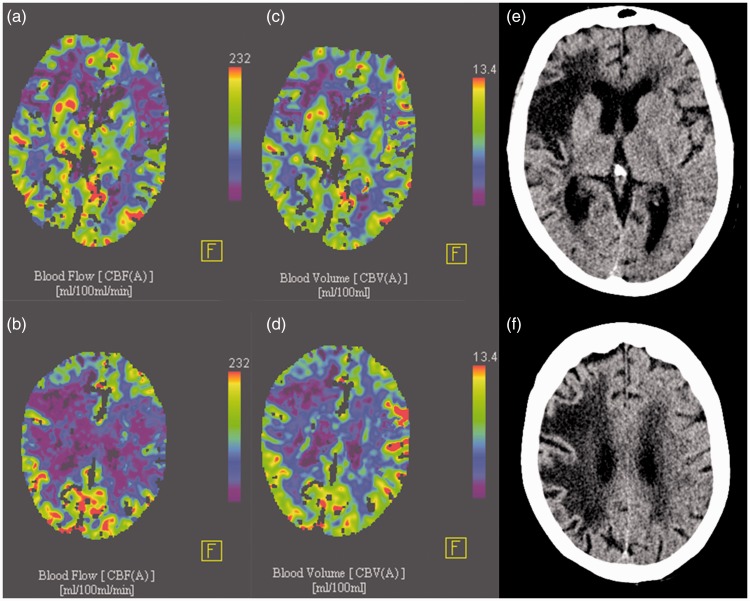

Figure 2.

(a, b) Cerebral blood flow images of the same (as in Figure 1) 79-year-old patient presenting with a right hemiparesis and aphasia nine hours after symptom onset. A cerebral blood flow-ASPECTS (Alberta stroke program early computed tomography scale) of four and a cerebral blood volume-ASPECTS of nine (c, d) were assigned indicating a small core and relevant mismatch, even nine hours after symptom onset. Follow-up noncontrast computed tomography images (e, f) of the same patient 52 hours after successful mechanical thrombectomy of the left medial cerebral artery thrombosis show no infarction of the left middle cerebral artery territory.

Discussion

In the pre-evidence era, the percentage of favourable outcome after mechanical thrombectomy was one of the most relevant endpoints in acute stroke therapy. Our data suggest that favourable outcome rates can be increased by implementing CBV-ASPECTS analysis as a patient selection criterion.

Limitations of our study include the retrospective design and the small number of cases. However, data were extracted from a prospectively assessed university hospital stroke database and included all patients with a M1 occlusion of the MCA treated in our department in the aforementioned time period.

Compared to historical data from our department, the two-point increase of median CBV-ASPECTS led to a 23% increase in favourable outcome (57% in our current dataset; 34% in the period 2007–2011) (publications anonymised for review purposes). Favourable outcome rates are known to be affected by better reperfusion rates and faster symptom-to-reperfusion times. However, even with better reperfusion quotas and faster time to successful reperfusion, only CBV-ASPECTS and age proved to be significant predictors of outcome (OR 4.10 and 0.84, respectively) in our study. A significant parameter that cannot be reconstructed with our data is the overall favourable outcome percentage of M1 occlusions (both treated and not treated due to imaging selection) in our hospital during this time period.

After publication of the MR CLEAN results, we decided to change our selection paradigm and started implementing noncontrast CT, as opposed to CTP, for imaging selection within the six-hour window. MR CLEAN was the trial with the loosest selection criteria (no ASPECTS restriction on noncontrast CT, CTP or use of collateral status) and thus showed a low percentage of favourable clinical outcome in the endovascular arm (33%), but nevertheless showed the superiority of endovascular therapy compared to i.v. rtPA alone (OD 1.66; 95% CI 1.21–2.28).1,2 The “Extending the Time for Thrombolysis in Emergency Neurological Deficits – Intra-Arterial” trial used CTP as a selection criterion and documented the highest percentage of favourable outcomes in the endovascular arm (72%).7 Our argument against such a tight selection paradigm in treating acute stroke patients with large artery occlusion within the first six hours is the reduction of patients treated with the most effective therapy. Untreated patients may still have profited from treatment, albeit not as much as those with a positive imaging profile. In contrast, there is no sufficient evidence from randomised trials about the advantages of a loose selection paradigm in the >6 hour time period.8,12

Multiple studies have shown the value of CTP and especially of CBV-ASPECTS in predicting favourable outcome after mechanical thrombectomy.3,9,11,13–15 As most of these studies included patients within the first six hours after symptom onset, one could argue that the predictive value of CBV-ASPECTS cannot be reliably applied to the six to 18 hour time window. However, data from the CT Perfusion to predict Response to recanalization in Ischemic Stroke Project presented at the International Stroke Conference 201616 suggest that a high percentage of patients with a CTP mismatch profile benefit from mechanical thrombectomy at 6–18 hours. This supports our current decision to select/exclude patients in the 6–18 hour window according to CTP analysis. Psychogios et al. reported in their study that a CBV-ASPECTS < 5 has a near 100% negative predictive value for good clinical outcome.11 Thus, our current consensus in favour of thrombectomy within the 6–18 hour window is primarily based, among other factors like age and previous clinical condition, on a CBV-ASPECTS ≥ 5.

Conclusion

Implementation of CTP imaging as a selection criterion of thrombectomy candidates significantly increased the rates of favourable clinical outcome within the treated population. Although CTP has lost impact within the six-hour period, it should be still considered in cases beyond six hours as a means to broaden the therapeutic window.

Author contributions

MNP, JL and MK designed the study and defined the concept and intellectual content. MNP prepared the manuscript. MNP, DB, RB, KS, IT and IM contributed in data acquisition and analysed data. IEP edited the manuscript. MK and DB guarantee the scientific integrity of the study.

Ethical standards

All patient data derived from the stroke database of the university hospital of Göttingen. Patients have given informed consent for all therapeutic decisions. Data were analysed retrospectively, fully anonymised, in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments as well as with the guidelines of the local Ethical Committee for clinical studies. No therapeutic decision has been influenced by the purpose of this study.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, et al. Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA alone in stroke. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2285–2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Psychogios MN, Kreusch A, Wasser K, et al. Recanalization of large intracranial vessels using the penumbra system: a single-center experience. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 1488–1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menon BK, Hill MD, Eesa M, et al. Initial experience with the Penumbra Stroke System for recanalization of large vessel occlusions in acute ischemic stroke. Neuroradiology 2011; 53: 261–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penumbra Pivotal Stroke Trial Investigators. The penumbra pivotal stroke trial: safety and effectiveness of a new generation of mechanical devices for clot removal in intracranial large vessel occlusive disease. Stroke J Cereb Circ 2009; 40: 2761–2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabbasch C, Mohlenbruch M, Stampfl S, et al. First-line lesional aspiration in acute stroke thrombectomy using a novel intermediate catheter: Initial experiences with the SOFIA. Interv Neuroradiol 2016; 22: 333–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, et al. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1009–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1019–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lum C, Ahmed ME, Patro S, et al. Computed tomographic angiography and cerebral blood volume can predict final infarct volume and outcome after recanalization. Stroke 2014; 45: 2683–2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsogkas I, Knauth M, Schregel K, et al. Added value of CT perfusion compared to CT angiography in predicting clinical outcomes of stroke patients treated with mechanical thrombectomy. Eur Radiol 2016; 26: 4213–4219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Psychogios MN, Schramm P, Frolich AM, et al. Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Scale evaluation of multimodal computed tomography in predicting clinical outcomes of stroke patients treated with aspiration thrombectomy. Stroke 2013; 44: 2188–2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet 2016; 387: 1723–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Padroni M, Bernardoni A, Tamborino C, et al. Cerebral Blood Volume ASPECTS Is the Best Predictor of Clinical Outcome in Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Retrospective, Combined Semi-Quantitative and Quantitative Assessment. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0147910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sillanpaa N, Saarinen JT, Rusanen H, et al. The clot burden score, the Boston Acute Stroke Imaging Scale, the cerebral blood volume ASPECTS, and two novel imaging parameters in the prediction of clinical outcome of ischemic stroke patients receiving intravenous thrombolytic therapy. Neuroradiology 2012; 54: 663–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jovin TG, Chamorro A, Cobo E, et al. Thrombectomy within 8 hours after symptom onset in ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2296–2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lansberg MG, Christensen S, Kemp S, et al. Abstract 57: Main Results of the CTP to Predict Response to Recanalization in Ischemic Stroke Project (CRISP). Stroke 2016; 47: A57–A57. [Google Scholar]