Abstract

The treatment of brain arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) remains a significant challenge, especially hemorrhagic AVMs which are unsuitable for microsurgery or radiosurgery. We demonstrate an AVM located in the left basal ganglia area, supplied by slender arteries, and treated by the transvenous pressure cooker technique. Herein, we describe the procedure and outline the crucial points and indications for this technique.

Keywords: Brain arteriovenous malformation, pressure cooker technique, transvenous embolization

Introduction

In recent years, the treatment for brain arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) has advanced significantly, and includes surgical resection, endovascular embolization, and radiosurgery. However, resection of AVMs located in the functional or deep areas may cause severe disability. Gamma knife is a long term treatment, with satisfactory results up to 2 years from radiosurgery. Treatment may fail due to recurrent hemorrhage and radio damage. Endovascular therapy with Onyx is an effective treatment, but not suitable for all patients with AVMs. Thus, the treatment of AVMs remains a significant challenge. Some difficult AVMs may be embolized through the transvenous approach.

The pressure cooker technique, or PCT, is a new endovascular technique that is often used in the treatment of dural arteriovenous fistula. While we know that transarterial PCT is a good treatment for brain AVMs, we do not know whether transvenous PCT is an approach that can contribute to the approach of transvenous embolism.

We describe a patient with an AVM located in the left basal ganglia area. The AVM was fed by slender arteries and drained by a single vein. The nidal diameter was approximately 2 cm. We treated this AVM by transvenous PCT. Herein, we describe the indications for and crucial points of this technique.

Clinical presentation

A 58-year-old female with a history of cerebroventricular hemorrhage 6 months prior to admission underwent diagnostic brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which revealed an AVM in the left basal ganglia area. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) revealed an AVM unsuitable for microsurgery or embolism treatment; gamma knife treatment was recommended. Four months later, the patient presented with a sudden headache following by unconsciousness several minutes later. She was admitted to our emergency department and computed tomography (CT) revealed a cerebroventricular hemorrhage with acute hydrocephalus. She underwent immediate insertion of an external ventricular drain (Figure 1). The patient underwent repeat DSA and the AVM was treated by transvenous PCT one week later. The AVM was fed by lenticulostriate arteries with some branches arising from the left anterior cerebral artery. The AVM had a single point of drainage and a small nidus measuring 2 cm in diameter (Figure 2).

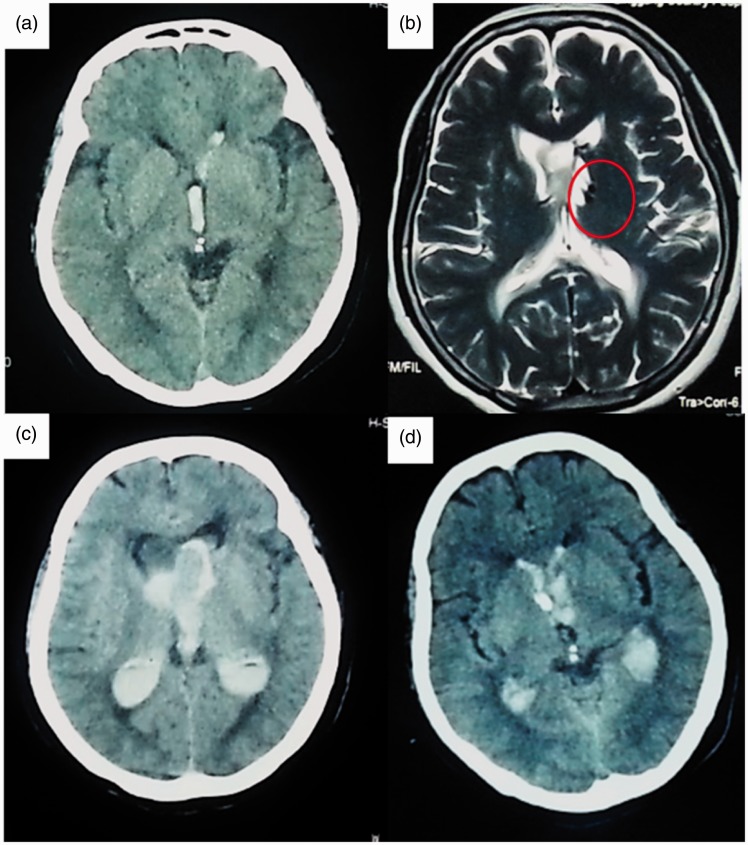

Figure 1.

(a) The first CT scan showed a cerebroventricular hemorrhage. (b) Diagnostic brain MRI revealed an AVM located in the left basal ganglia area. Gamma knife treatment was then recommended. (c) Four months later, the patient presented with a severe headache followed by unconsciousness and repeat CT revealed a cerebroventricular hemorrhage with acute hydrocephalus. She underwent immediate external ventricular drainage. (d) CT scan after external ventricular drainage.

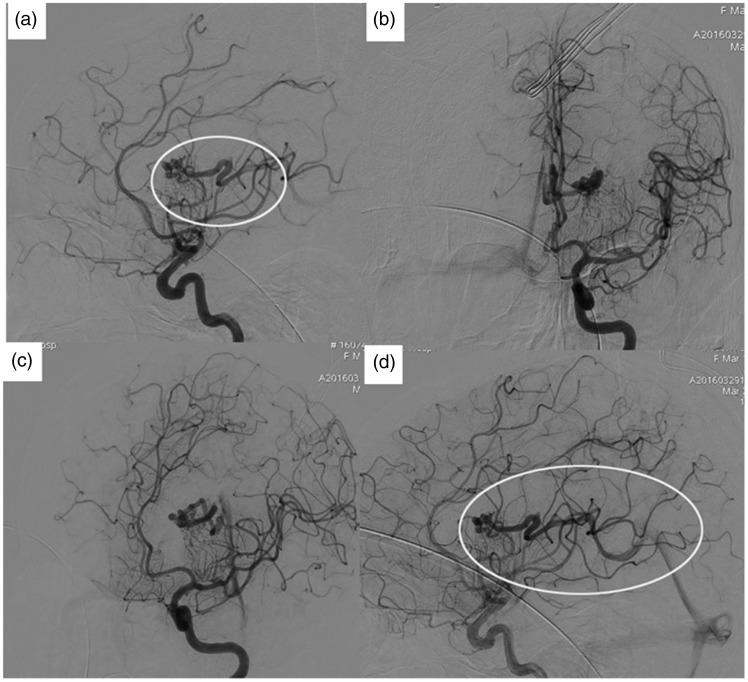

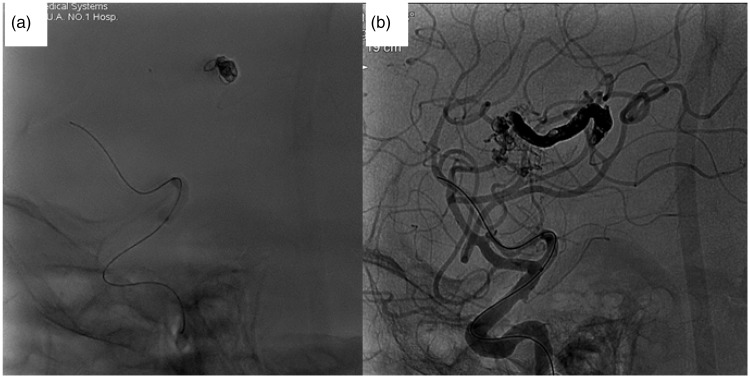

Figure 2.

DSA revealed an AVM fed by the lenticulostriate arteries and some branches arising from the left anterior cerebral artery. The AVM had a single drainage site and a small nidus measuring 2 cm in diameter.

Technical description

The patient was placed under general endotracheal anesthesia with full heparinization. We used right transfemoral access to obtain angiograms and placed a balloon in the internal carotid artery. Through the left femoral vein, a 6-French guiding catheter was placed in the left internal jugular vein. A microcatheter (Sonic, Balt, Montmorency, France) was placed as close as possible to the nidus (Figure 3).

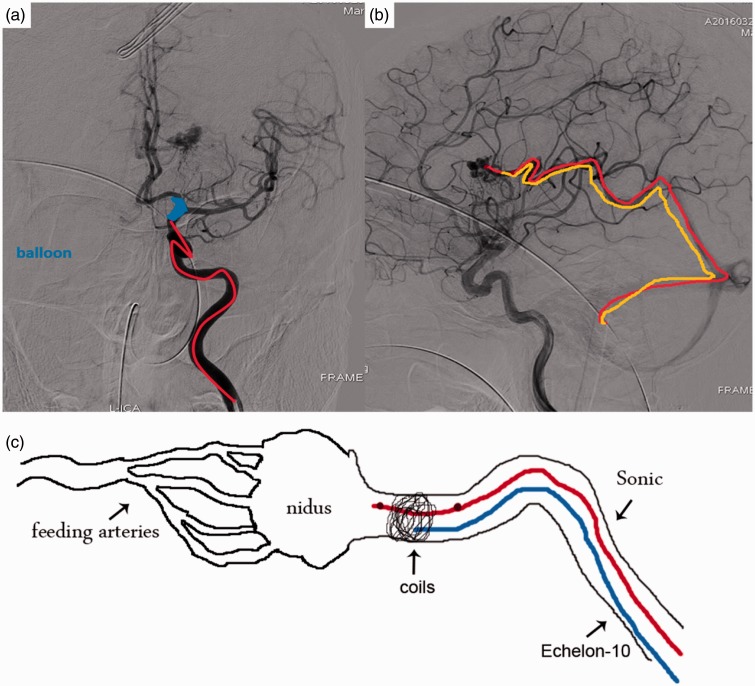

Figure 3.

Diagrammatic sketch of transvenous PCT.

Then, another microcatheter (Echelon-10, Ev3, Irvine, CA) was navigated alongside the Sonic into the draining vein. Its tip was positioned between the most distal marker and the detachment zone of the Sonic microcatheter. We placed coils into the draining vein through the Echelon-10 microcatheter to create a plug (Figure 4). These coils served three main purposes:

by coiling upstream of the drainage, this technique could protect these possible confluent veins into the draining vein from being occluded;

to prevent the Onyx (Ev3, Irvine, CA) from refluxing and causing pulmonary embolism;

to increase the operator’s ability to push more Onyx continuously into the nidus.

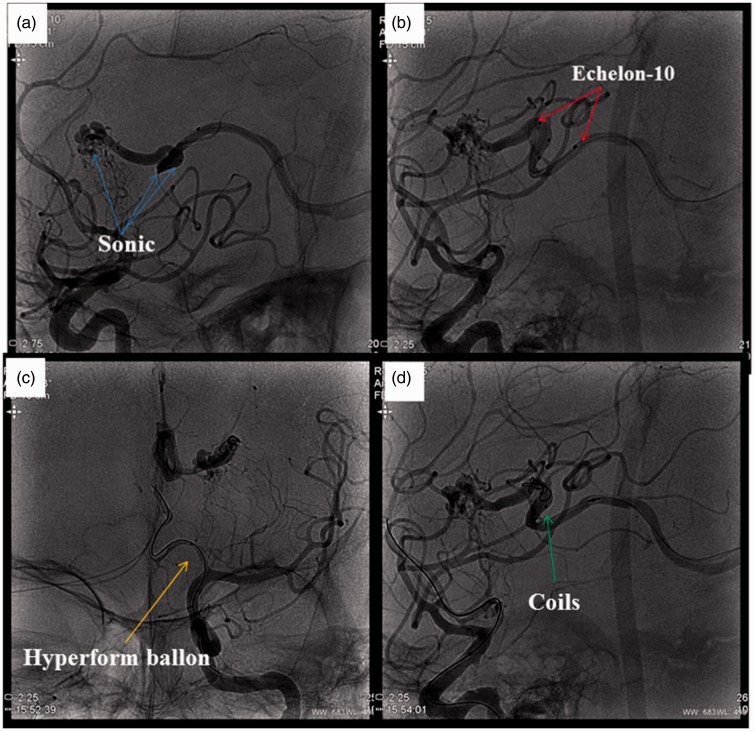

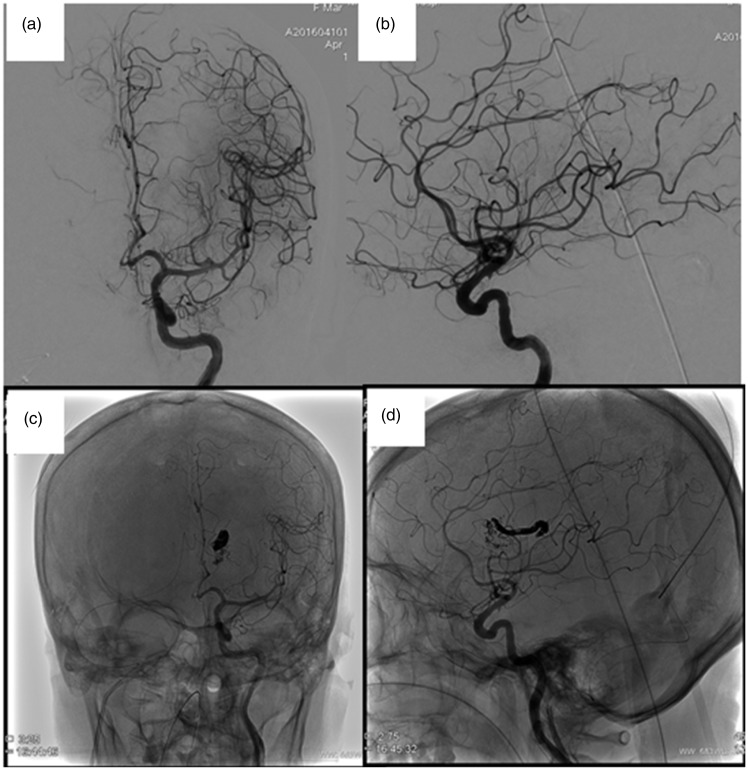

Figure 4.

(a) A microcatheter (Sonic, Balt, France) was placed as close as possible to the nidus. (b) Another microcatheter (Echelon-10, Ev3, Irvine, California, USA) was navigated alongside the Sonic into the draining vein. Its tip was positioned between the most distal marker and the detachment zone of the Sonic. (c) A balloon was placed from the anterior cerebral artery to the end of the carotid artery. (d) Then, coils were placed in the draining vein through the Echelon-10 microcatheter to create a plug.

Before Onyx injection, we used a hyperform balloon (Ev3, Irvine, CA) to block the left internal carotid artery, in order to decrease the feeding arteries’ flows and nidal pressures.

After these three procedures, we injected Onyx slowly but at a higher rate than the arterial injection. A reflux of Onyx was tolerated, unless it went across the coils. (In the instructions for use, Onyx should be injected under low pressure over several minutes to create a safe proximal plug and minimize Onyx backflow, particularly during the initial stage; Figure 5). After full retrograde filling of the nidus with Onyx and anatomic obliteration of the AVM, we detached the tip of the Sonic microcatheter and retrieved it carefully. Then, the control DSA confirmed anatomic resolution of the lesion (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Onyx was injected slowly, but at a higher rate than arterial injection.

Figure 6.

After treatment, control DSA confirmed anatomic resolution of the lesion.

Discussion

A few reports have described successful transvenous embolization of brain AVMs but transvenous embolism is still a hazardous choice.1,2 It may cause severe intracranial hemorrhage and pulmonary embolism. The transvenous PCT, a new endovascular approach, may contribute to the safety of embolization. The technique can be traced to treatment of dural arteriovenous fistulas,3 but transvenous PCT has never been described for brain AVMs.

When to consider the transvenous PCT

The size, location, and symptomatology of an intracranial AVM can determine the type of treatment.4 The patient described in this case report had a small size AVM located in the deep left basal ganglia area, with slender feeding arteries, so was unsuitable for transarterial embolism, microsurgery, and radiosurgery for her history of recurrent ventricular hemorrhage.4 Transvenous embolization may have been the only treatment for this patient.

It is known that transvenous PCT cannot replace traditional embolism. But, being similar to the indications for simple transvenous embolism, transvenous PCT may be a good choice in the following special cases:2

deep brain AVMs – unsuitable for surgical resection;

failed gamma knife treatment;

slender feeding artery, unsuitable for transarterial embolism;

hemorrhagic AVMs

diameter of nidus less than 2 cm;

drained by a single vein and could be easy navigated.

Thus, transvenous PCT may make the treatment of these AVMs safer and easier.

However, this technique may have disadvantages compared to transvenous approach alone. It may be difficult and dangerous to navigate with stiffer microcatheter to put coils in small and fragile veins.

The crucial points of transvenous PCT

It was important to maintain venous egress until the nidus was eliminated, and prevent the Onyx from refluxing.5,6 The crux depended on three points. One was systemic and local hypotension at the AVM nidus; in other words, in order to control blood pressure and temporary occlude the feeding arteries, we placed a balloon from the anterior cerebral artery to the end of the carotid artery.7 This placement could also block the blood from the anterior communicating artery. Blood arrest decreased draining vein pressure, and contributed to injecting Onyx into the nidus.8 Another crucial point was placing the venous microcatheter as close as possible to the nidus. Finally, it was important to embolize the nidus as much as possible. In our case, transvenous Onyx completely filled the venous pouch.

Is a detachable microcatheter a good choice?

A detachable microcatheter has previously been used in transvenous treatment, and in this case, we also used a detachable microcatheter to inject Onyx.9 We detached the tip of the catheter and retrieved it successfully, but more power was required during this procedure than previously expected. Thus, this could be a pitfall and may injure the draining vein.10 Fortunately, this did not occur in our case. However, we also advise to cut the microcatheter with a blade at the level of the jugular sheath after treatment. According to initial experience, other complications are not anticipated.

Conclusions

The transvenous PCT is a good approach for certain cases, particularly for hemorrhagic AVMs unsuitable for traditional therapy. The transvenous PCT may enlarge the range of AVMs amenable to curative embolization.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Consoli A, Renieri L, Nappini S, et al. Endovascular treatment of deep hemorrhagic brain arteriovenous malformations with transvenous onyx embolization. Am J Neuroradiol 2013; 34: 1805–1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler I, Riva R, Ruggiero M, et al. Successful transvenous embolization of brain arteriovenous malformations using Onyx in five consecutive patients. Neurosurgery 2011; 69: 184–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loumiotis I, Cloft HJ, Lanzino G. Intercavernous sinus dural arteriovenous fistula successfully treated with transvenous embolization. a case report. Interv Neuroradiol 2011; 17: 208–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peschillo S, Caporlingua A, Colonnese C, et al. Brain AVMs: an endovascular, surgical, and radiosurgical update. Sci World J 2014; 2014: 834931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choudhri O, Ivan ME, Lawton MT. Transvenous approach to intracranial arteriovenous malformations: challenging the axioms of arteriovenous malformation therapy? Neurosurgery 2015; 77: 644–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steiger HJ, Hanggi D. Retrograde venonidal microsurgical obliteration of brain stem AVM: a clinical feasibility study. Acta Neurochir 2009; 151: 1617–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massoud TF. Transvenous retrograde nidus sclerotherapy under controlled hypotension (TRENSH): hemodynamic analysis and concept validation in a pig arteriovenous malformation model. Neurosurgery 2013; 73: 332–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapot R, Stracke P, Velasco A, et al. The pressure cooker technique for the treatment of brain AVMs. J Neuroradiol 2014; 41: 87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Limbucci N, Spinelli G, Nappini S, et al. Curative transvenous Onyx embolization of a maxillary arteriovenous malformation in a child: report of a new technique. J Craniofacial Sur 2016; 27: e217–e219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendes GA, Iosif C, Silveira EP, et al. Transvenous embolization in pediatric plexiform arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery 2016; 78: 458–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]