Abstract

The rapidly-acting antidepressant properties of ketamine are a trend topic in psychiatry. Despite its robust effects, these are ephemeral and can lead to certain adverse events. For this reason, there is still a general concern around the off-label use of ketamine in clinical practice settings. Nonetheless, for refractory depression, it should be an indication to consider. We report the case of a female patient admitted for several months due to a treatment-resistant depressive bipolar episode with chronic suicidal behaviour. After repeated intravenous ketamine infusions without remarkable side effects, the patient experienced a complete clinical recovery during the 4 weeks following hospital discharge. Unfortunately, depressive symptoms reappeared in the 5th week, and the patient was finally readmitted to hospital as a result of a suicide attempt.

Keywords: antidepressive agents, bipolar disorder, depression, ketamine, suicide

Introduction

Ketamine, a noncompetitive antagonist of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) subtype of excitatory amino acid receptor, is a dissociative anaesthetic agent [Krystal et al. 1994]. It is commonly handled in anaesthesiology due to its safety in various clinical conditions, being used more in the paediatric population [Green et al. 2011]. Nevertheless, its management in adult patients has been controversial based on dissociative and psychotomimetic side effects [Strayer and Nelson, 2008], a fact that has led to its popularity as a drug of abuse [Schifano et al. 2008].

The first study showing the antidepressant effects of ketamine was reported 15 years ago [Berman et al. 2000]. Since then, a substantial body of evidence has gradually accumulated, as evidenced by several recently published systematic reviews and meta-analyses [Caddy et al. 2013; Kishimoto et al. 2014; Fond et al. 2014; Coyle and Laws, 2015; Lee et al. 2015; McGirr et al. 2015; Romeo et al. 2015; Parsaik et al. 2015; Xu et al. 2016; Alberich et al. 2016]. In these, the rapid and robust antidepressant and anti-suicidal properties of ketamine are highlighted, while there are warnings about its temporary effect and the methodological difficulties of double-blind trials [Aan Het Rot et al. 2012]. Consequently, the main objective of future research is to determine how best to sustain ketamine’s efficacy. It has been established that repeated infusions achieve superior outcomes compared with a single infusion [Murrough et al. 2013; Shiroma et al. 2014; Rasmussen et al. 2013; Diamond et al. 2014; Singh et al. 2016; Cusin et al. 2016], but strategies for maintenance are still lacking. Therefore, despite the enthusiasm generated, the off-label use of ketamine is still not yet widespread in clinical practice for treatment-refractory depression (TRD). For example, at the time of writing only two case reports have been published in Spain. [Cortiñas-Saenz et al. 2013; Montes et al. 2015].

Case

Clinical background

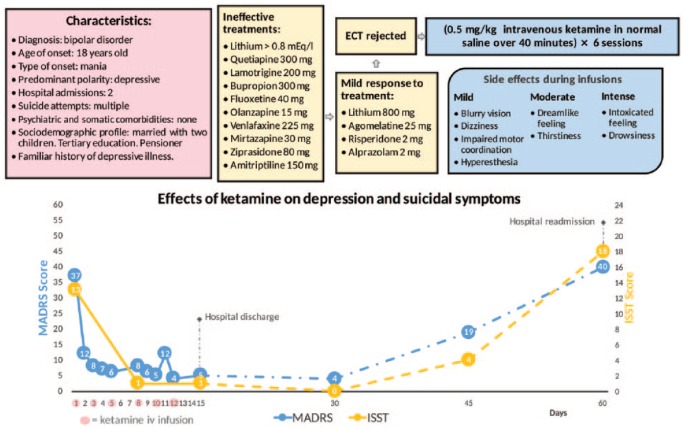

A 45-year-old female patient with refractory bipolar depression (as assessed in a structured psychiatric interview) and chronic suicidal thoughts was admitted to care after an aborted suicide attempt at home. During admission, her evolution was underlined by the presence of major depressive feelings of hopelessness and intense anxiety levels that led the patient to exhibit recurring suicidal behaviour.

Several changes of medication (antidepressants, mood stabilisers and antipsychotics) and intensive programmes of psychotherapy were carried out, all of which were ineffective. A pharmacogenetic test (Neuropharmagen® AB Biotics, Spain) was conducted in order to identify the most suitable medication, with no findings of a specific profile in favour of certain psychotropic drugs. A lack of response to antidepressant treatment was established after a 4-week course at the doses recommended in the datasheet. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) was offered but rejected by the patient, citing stigma and side effects. Without further possible therapeutic resources at our disposal, and 6 months after her hospitalisation, the off-label use of ketamine was put forward. Authorisation was requested from the hospital’s ethics committee, department of pharmacy and medical director, all approving the indication after a detailed technical report. With the informed consent of the patient and her relatives, all ethical requirements were met, leading to the treatment then being initiated (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of ketamine on depression and suicidal symptoms.

ECT, electroconvulsive therapy; ISST, InterSePT Scale for Suicidal Thinking; MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale.

Intravenous ketamine therapy

According to previously obtained evidence [Murrough et al. 2013; Shiroma et al. 2014; Rasmussen et al. 2013; Diamond et al. 2014], repeated administration was chosen, at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg of intravenous ketamine in normal saline over 40 min on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays over 2 weeks (i.e. six sessions in total). Previous oral medication was sustained at the same doses because, although it was ineffective for depressive symptoms, it was useful to treat anxiety, impulsivity and sleep disturbances. Psychometric assessment included the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and the InterSePT Scale for Suicidal Thinking (ISST). Vital signs (blood pressure and heart rate) and side effects were periodically measured up to 4 h after each infusion.

Results

An impressive clinical response was registered just a few hours after the first session. In the following five infusions, this improvement was successfully consolidated, abating symptoms of depression and suicide risk. At 2 weeks after the start of treatment, the patient was discharged from hospital and referred to outpatient psychiatric care. Euthymia was maintained for 4 weeks, in which the patient developed a functional recovery process. Unfortunately, this positive course was cut short in the 5th week, during which depressive symptoms abruptly reappeared until another suicide attempt brought about readmission to hospital (see Figure 1). In addition, it is notable that the episode remitted despite the fact that the patient was taking alprazolam. Recently, a number of authors have shown that benzodiazepines may attenuate the effectiveness of ketamine when administered concomitantly [Ford et al. 2015; Frye et al. 2015], although this interaction has been observed only in non-responsive patients.

With regard to side effects, these were confined to the period of ketamine infusion and were mainly of a sedative nature, disappearing entirely within the following 2 h. Neither psychotomimetic nor dissociative effects were recorded, as noted in several papers [Rasmussen et al. 2013; Diamond et al. 2014; Montes et al. 2015; Singh et al. 2016; Cusin et al. 2016]. Vital signs were also undisturbed (see Figure 1).

Discussion

The mechanism underlying the antidepressant effect of ketamine is complex and not yet well understood [Newport et al. 2015]. At low doses, ketamine might rapidly increase synaptic glutamate release and expression of the α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor, and relieve inhibition of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) synthesis [Romeo et al. 2015]. Furthermore, in animal models, ketamine activates the pathway involving the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and is conducive to synaptogenesis in neural circuits damaged due to chronic depression and stress [Li et al. 2010]. All these properties, which differ from the usual mechanisms of current antidepressants, place ketamine in a central role for the development of new interventions in TRD [Abdallah et al. 2015]. However, there is still caution over its use in clinical practice because of the risks of abuse and the occurrence of adverse effects (dissociative and psychomimetic) during administration although in this case report the patient did not present any notable side effect.

In the view of the authors, intravenous ketamine infusion is an intervention to be considered in hospital settings when patients with TRD have recurrent suicidal ideations. The next challenge is what to do when depressive symptoms return, which is the norm, as can be seen in this case report.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patient for her informed consent to the use of her clinical documentation for publication.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Álvaro López-Díaz, Hospital San Juan de la Cruz, Mental Health Inpatient Unit, Úbeda, Jaén, Spain.

José Luis Fernández-González, Hospital San Juan de la Cruz, Mental Health Inpatient Unit, Úbeda, Jaén, Spain.

José Evaristo Luján-Jiménez, Hospital San Juan de la Cruz, Mental Health Inpatient Unit, Úbeda, Jaén, Spain.

Sara Galiano-Rus, Hospital San Juan de la Cruz, Mental Health Inpatient Unit, Úbeda, Jaén, Spain.

Luis Gutiérrez-Rojas, Hospital San Juan de la Cruz, Mental Health Inpatient Unit, Úbeda, Jaén, Spain.

References

- Aan Het Rot M., Zarate C., Charney D., Mathew S. (2012) Ketamine for depression: where do we go from here? Biol Psychiatry 72: 537–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah C., Sanacora G., Duman R., Krystal J. (2015) Ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: a window into a new neurobiology for mood disorder therapeutics. Annu Rev Med 66: 509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberich S., Martínez-Cengotitabengoa M., López P., Zorrilla I., Núñez N., Vieta E., et al. (2016) Efficacy and safety of ketamine in bipolar depression: a systematic review. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment pii S1888–9891(16): 30025–30028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman R., Cappiello A., Anand A., Oren D., Heninger G., Charney D., et al. (2000) Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry 47: 351–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caddy C., Giaroli G., White T., Shergill S., Tracy D. (2013) Ketamine as the prototype glutamatergic antidepressant: pharmacodynamics actions, and a systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 4: 75–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortiñas-Saenz M., Alonso-Menoyo M., Errando-Oyonarte C., Alférez-García I., Carricondo-Martínez M. (2013) Effect of sub-anaesthetic doses of ketamine in the postoperative period in a patient with uncontrolled depression. Rev Esp Anestesiol 60: 110–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle C., Laws K. (2015) The use of ketamine as an antidepressant: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Psychopharm Clin 30: 152–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusin C., Ionescu D., Pavone K., Akeju O., Cassano P., Taylor N., et al. (2016) Ketamine augmentation for outpatients with treatment-resistant depression: preliminary evidence for two-step intravenous dose escalation. Aust N Z J Psychiatry pii: 0004867416631828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond P., Farmery A., Atkinson S., Haldar J., Williams N., Cowen P., et al. (2014) Ketamine infusions for treatment resistant depression: a series of 28 patients treated weekly or twice weekly in an ECT clinic. J Psychopharmacol 28: 536–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye M., Blier P., Tye S. (2015) Concomitant benzodiazepine use attenuates ketamine response implications for large scale study design and clinical development. J Clin Psychopharmacol 35: 334–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fond G., Loundou A., Rabu C., Macgregor A., Lançon C., Brittner M., et al. (2014) Ketamine administration in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 231: 3663–3676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford N., Ludbrook G., Galletly C. (2015) Benzodiazepines may reduce the effectiveness of ketamine in the treatment of depression. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 49(12): 1227–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green S., Roback M., Kennedy R., Krauss B. (2011) Clinical practice guideline for emergency department ketamine dissociative sedation: 2011 update. Ann Emerg Med 57: 449–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto T., Chawla J., Kane J., Correll C. (2014) Ketamine and non-ketamine NMDA receptor antagonists for unipolar and bipolar depression: a meta-analysis. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 17: 56–57. [Google Scholar]

- Krystal J., Karper L., Seibyl J., Freeman G., Delaney R., Bremner J., et al. (1994) Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, ketamine, in humans: psychotomimetic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry 51: 199–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E., Della Selva M., Liu A., Himelhoch S. (2015) Ketamine as a novel treatment for major depressive disorder and bipolar depression: a systematic review and quantitative meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 37: 178–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Lee B., Liu R., Banasr M., Dwyer J., Iwata M., et al. (2010) mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists. Science 329: 959–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGirr A., Berlim M., Bond D., Fleck M., Yatham L., Lam R. (2015) A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of ketamine in the rapid treatment of major depressive episodes. Psychol Med 45: 693–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montes J., Luján E., Pascual F., Beleña J., Perez-Santar J., Irastorza L., et al. (2015) Robust and sustained effect of ketamine infusions coadministered with conventional antidepressants in a patient with refractory major depression. Case Rep Psychiatry 2015: 815673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrough J., Perez A., Pillemer S., Stern J., Parides M., Aan het Rot M., et al. (2013) Rapid and longer-term antidepressant effects of repeated ketamine infusions in treatment-resistant major depression. Biol psychiatry 74: 250–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport D., Carpenter L., McDonald W., Potash J., Tohen M., Nemeroff C. (2015) Ketamine and other NMDA antagonists: early clinical trials and possible mechanisms in depression. Am J Psychiatry 172: 950–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsaik A., Singh B., Khosh-Chashm D., Mascarenhas S. (2015) Efficacy of ketamine in bipolar depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Pract 21: 427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K., Lineberry T., Galardy C., Kung S., Lapid M., Palmer B., et al. (2013) Serial infusions of low-dose ketamine for major depression. J Psychopharmacol 27: 444–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo B., Choucha W., Fossati P., Rotge J. (2015) Meta-analysis of short- and mid-term efficacy of ketamine in unipolar and bipolar depression. Psychiatry Res 230: 682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schifano F., Corkery J., Oyefeso A., Tonia T., Ghodse A. (2008) Trapped in the “K-hole”: overview of deaths associated with ketamine misuse in the UK (1993–2006). J Clin Psychopharmacol 28: 114–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiroma P., Johns B., Kuskowski M., Wels J., Thuras P., Albott C., et al. (2014) Augmentation of response and remission to serial intravenous subanesthetic ketamine in treatment resistant depression. J Affect Disord 155: 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J., Fedgchin M., Daly E., De Boer P., Cooper K., Lim P., et al. (2016) A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-frequency study of intravenous ketamine in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry 173: 816–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strayer R., Nelson L. (2008) Adverse events associated with ketamine for procedural sedation in adults. Am J Emerg Med 26: 985–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Hackett M., Carter G., Loo C., Gálvez V., Glozier N., et al. (2016) Effects of low-dose and very low-dose ketamine among patients with major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 20: 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]