Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Due to the increasing number of elderly and an increase in the number of cases of cancer by age, cancer is a common problem in the elderly. For elderly patients with cancer, the disease and its treatment can have long-term negative effects on their quality of life (QoL). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of progressive muscle relaxation, body image and deep diaphragmatic breathing on the QoL in the elderly with cancer.

Materials and Methods:

This study was a randomized controlled trial in which 50 elderly patients with breast or prostate cancer were randomized into study and control groups. Progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, and deep diaphragmatic breathing were given to the study group, but not to the control group. The effect of the progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery and deep diaphragmatic breathing was measured at three different time points. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and QoL Questionnaire-Core questionnaires was completed before, after and 6 weeks after the intervention for the patients in both groups simultaneously. The data were analyzed by SPSS.

Results:

There was statistically significant improvement in QoL (P < 0.001) and physical functioning (P < 0.001) after progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery and deep diaphragmatic breathing intervention.

Conclusions:

The findings indicated that concurrent application of progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, and deep diaphragmatic breathing would improve QoL in the elderly with breast or prostate cancer.

Keywords: Cancer, diaphragmatic breathing, elderly, guided imagery, progressive muscle relaxation, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Cancer, as one of the health problems, has a rapid ascending trend in the world,[1] and is counted as the second cause of mortality in the world. In Iran, it is the third cause of mortality. Based on WHO prediction, incidence of cancer in Iran will reach 85,000 cases from all population with mortality rate of 62,000 in year 2020.[2]

Cancer is a common problem among the elderly.[3] With regard to the increasing trend of older adults’ population in the world (with an increase from 605 million in year 2000 to 2 billion in 2050), the number of cancer patients is expected to increase.[4] In USA, older adults comprise almost 60% of the 11 million cancer patients.[3] In Iran, cancer is the third mortality cause, and WHO reports its annual mortality as 12%.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women. In year 2013, 234,000 new cases of breast cancer were reported in US, of which 39,000 led to death.[5] Prostate cancer is the second known cancer in men with the highest rate in developed countries and the lowest in Far East countries.[6] In 2013, almost 238,000 new cases of prostate cancer were reported in US of which 29,000 resulted in death.[5] Not only cancer itself but also its complications and side effects of the treatments, as well as length of disease, can have numerous negative effects on patients’ function and quality of life (QoL).[7] Various studies showed that cancer and its treatment can result in physical, emotional and social pressure that lead to a reduction in function, incidence of sexual function disorder, and a change in body image, followed by probable structural changes, a reduction in self-confidence and possibility of familial, emotional, and economic problems, anxiety and suffering from psychological problems, and a severe reduction in psychological and physical function[8] that can influence QoL of the individuals and their families.[9] Long-term complications of treatment such as incontinence, sexual disability, and inflammation of the rectum due to radiotherapy have negative effects on the elderly.[10] Various treatments are administered for the patients with different goals to control the signs, relieve pain, prolong life and improve QoL, but they cannot fulfill all patients’ needs.[11] Therefore, using complementary methods to reduce patients’ problems seems necessary. With regard to the high prevalence of cancer among the elderly, incidence of numerous complications due to cancer and its treatment, high costs of treatment, severe effects of the disease and trend of treatment on their physical and psychological conditions, non meditational methods can be adopted. One of the basic and low-risk interventions, which can be used parallel to the treatment for these patients, is complementary or alternative medicine.[11] Using different methods of complementary, alternative medicine is more common among cancer patients, compared to other patients.[12] Research showed that adopting such methods can affect sign and complications control among cancer patients. On the other hand, these methods are the most cost effective, efficient and functional methods and have lower complications[13] and are less invasive and addictive, and more accessible, compared to other treatments. These methods can improve QoL, as a goal of WHO in its program of “health for all,” through causing an increase in the years of patients’ life. It should be also noted that although cancer patients need support, physicians do not fulfill their needs as they should.[14]

One of the complementary medicine methods is using behavioral intervention such as progressive muscle relaxation and body – mind interventions such as guided imagery. Progressive muscle relaxation is a physical stimulation and mental peace with emphasis on muscle systematic stretching and release (contraction-release).[15] Progressive muscle relaxation can be applied in all stages of cancer patients and can notably reduce cancer complications.[16]

Guided imagery is also one of the complementary medicine methods that can be applied in different conditions and in various populations to improve QoL and reduce cancer pain.[17] Guided imagery of beautiful and attractive views causes endorphins to release in the body leading to feeling of peace and removal of stressful thoughts, and consequently, feeling of euphoria. It should be noted that no complications have been yet reported for this technique.[18]

Deep diaphragmatic breathing is a sort of purposive smoother, deeper and standard breathing through which the person achieves peace and comfort and is one of the relaxation methods that provides the body with more oxygen. Good respiration behaviors increase individuals’ ability to cope with physical tension and lead to stress management.[19]

Concurrent application of relaxation methods can affect QoL in cancer patients.[15] With regard to the reduction in QoL of the older adults with cancer and aging trend of population in Iran as well as high prevalence of breast or prostate cancers in Iranian older adults, the necessity of applying such non meditational methods in these patients with no complications is of paramount importance. On the other hand, about no side effects in non meditational method, and their positive effects on QoL, nurses can use these methods for the patients. As no study has investigated concurrent application of three methods of complementary medicine in older adults with cancer so far, the present study aimed to define the effect of progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery and deep diaphragmatic breathing on QoL of the older adults with breast or prostate cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a two-group three-stage clinical trial, conducted in Seyed-Al-Shohada University Hospital in Isfahan, Iran in 2013. Effect of concurrent guided imagery, progressive muscle relaxation and deep diaphragmatic breathing on QoL in the elderly with cancer was investigated before, immediately after and 6 weeks after the intervention in study and control groups.

With regard to similar studies and consideration of test power of 0.80, the number of the subjects was calculated 25 in each group (n = 25, n = 25). Inclusion criteria were age over 65 years, involvement in breast or prostate cancer, not undergoing chemotherapy, absence of any metastasis and adequate physical ability to administrate relaxation techniques.

Exclusion criteria were progression of the disease, incidence of metastasis, beginning of advanced treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery, and any physical disability occurring among the subjects preventing the intervention. Firstly, based on inclusion criteria, the subjects were selected through convenient sampling, and then, were assigned to study and control groups through random allocation. Word “study” and “control” were written on two cards, which were put into a bag. A person, unaware of the research, was asked to take out one the cards and the subjects were assigned to either control or study group accordingly. Sampling lasted for 5 months from May to December 2014.

Data were collected by a two-section questionnaire and referring to patients’ medical files. The first section of the questionnaire was on demographic characteristics, and the second was QoL questionnaire of European Cancer Organization. This multi-dimensional questionnaire contained 30 item of QoL in five functional domains (physical, role play, emotional, cognitive, and social), nine domains of signs (fatigue, pain nausea and vomiting, respiration distress, diarrhea, constipation, loss of sleep, loss of appetite and economic problems due to the disease), and one general domain of QoL. Scoring of two items of general QoL was based on a seven-point Likert's scale, and the rest, based on a four-point Likert's scale. During data analysis stage, the scores were calculated between 0 and 100. In functional and general domains of QoL, higher scores showed a better condition and QoL. Meanwhile, a higher score in the domain of signs revealed more problems. This questionnaire has been frequently adopted in domestic and international studies and enjoys an established validity and reliability. Its validity and reliability were investigated in the study. Study of Safaei and Tabatabaei in which Cronbach alpha = 0.7 showed a proper reliability.[20]

First of all, the goal of the study was explained, and adequate information was given to the patients and their accompanying persons, and an informed written consent was obtained from them. They were assured about the confidentiality of their data and their right to leave the study whenever they liked. Then, the subject filled the questionnaire with the help of his/her accompanying person.

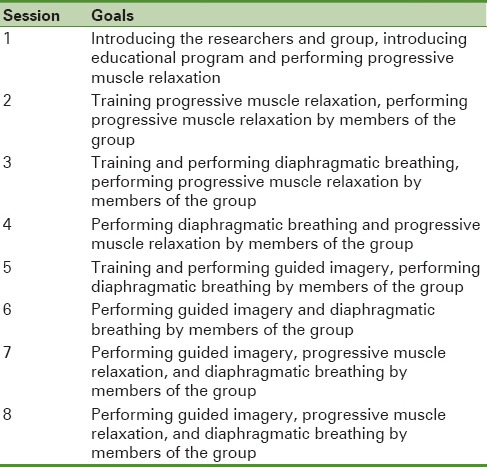

In study groups, the subjects were asked to attend an appropriate place in the hospital with one of their caregivers. Attendance of the caregiver was obligatory due to subjects’ high age and their need to be assisted in learning. The subjects in study group were divided into two groups of eight members and one group of seven members. Education and practice sessions were separately held for each group in form of eight 45-min sessions during four sequential weeks as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Education and practice sessions in study group

In the present study, progressive muscle relaxation referred to contraction and release of muscles for eight groups of muscles (lower hand, upper hand, lower leg and upper leg, abdomen, shoulders, lower chest and upper forehead), showed to the subjects through data show while being asked to imitate the practice.

In deep diaphragmatic breathing technique, the subjects were asked to be in a comfortable position and to put one hand on the abdomen and the other on their chest. The subjects were asked to gently breathe through their nose, gently count until number four while inhaling and feel their abdomen rising with their hand. Then, after number four, they gently exhaled, and waited for 4 s before next inhalation. This practice was administrated for 2 min.

Guided imagery was conducted in a way that firstly, pictures from relaxing sceneries were shown to the patients, and they were asked to visualize the scenery that was the most pleasant to them for 10–15 min. The subjects in study group were asked to conduct this technique at least twice a day at home.

After a 1-month education and practice period, the patients were asked to complete QoL questionnaire once more. These techniques were also conducted for 6 weeks under indirect supervision of the researcher. The researcher followed-up correct administration of the techniques through phone calls and getting information from the patients’ caregivers. After 6 weeks, QoL questionnaire was completed once more in study group.

In control group, three usual sessions on lifestyle and life experiences were conducted, and QoL questionnaire was filled concurrently with study group before, immediately after and 6 weeks after the intervention. Data were analyzed by paired t-test, independent t-test, and repeated measures ANOVA through SPSS 20 (IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

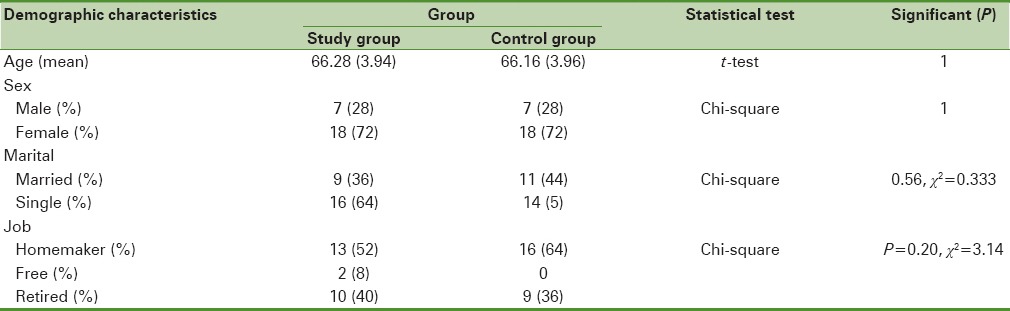

Demographic characteristics showed that both groups were homogenous concerning the demographic characteristics (there was no significant difference) as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the subjects in study and control groups

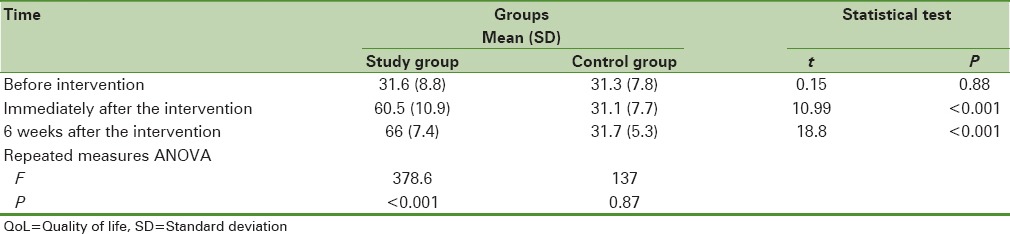

Independent t-test showed no significant difference in mean scores of functional domains before intervention between two groups (P = 0.88), but showed a significant increase in mean scores of functional domains in study group immediately after (P < 0.001), and 6 weeks after intervention (P < 0.001) [Table 3]. Repeated measure ANOVA showed no significant difference in mean scores of QoL in functional domains between 3 times points in the control group (P = 0.87). In study group, there was a significant difference (P < 0.001). Least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test showed that mean score of functional domain of QoL was significantly higher immediately after intervention, compared to before (P < 0.001), and 6 weeks after intervention, compared to immediately after respectively (P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Determination and comparison of the differences in the mean scores of functional domains of QoL between two groups before, immediately after and 6 weeks after the intervention

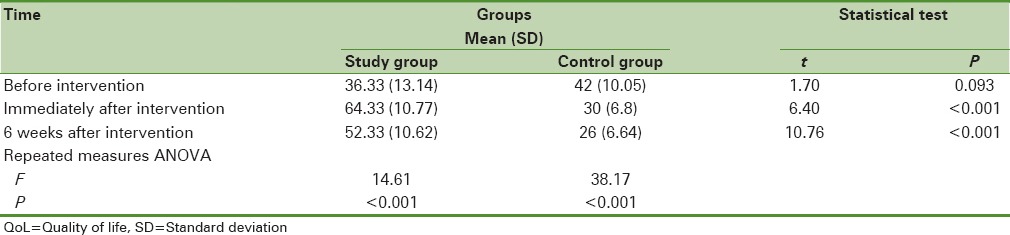

Repeated measure ANOVA showed that mean scores of QoL overall domain were not the same in study group (P < 0.001). LSD post hoc showed that mean scores of QoL overall domain were significantly higher immediately after intervention, compared to before (P < 0.001) and 6 weeks after, compared to immediately after intervention respectively (P < 0.001).

Repeated measure ANOVA showed that mean scores of QoL overall domain were not the same in 3 times points (P < 0.001) in control group, but LSD post hoc showed that mean score of QoL overall domain was significantly less after intervention, compared to before intervention (P < 0.001), and 6 weeks after intervention, compared to immediately after (P < 0.001).

Independent t-test showed no significant difference in mean scores of QoL overall domain between two groups before intervention (P = 0.093), but after intervention (P < 0.001) and 6 weeks after (P < 0.001), mean scores of QoL overall domain were significantly more in the study group, compared to control group [Table 4].

Table 4.

Determination and comparison of the differences in the mean scores of general domain of QoL between two groups before, immediately after and 6 weeks after intervention

DISCUSSION

The results showed that mean scores of functional and overall domains of QoL had a significant difference immediately after and 6 weeks after the intervention in study group, compared to control. It shows the positive effect of concurrent application of three relaxation techniques of progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery and diaphragmatic deep breathing on improvement of QoL in the older adults with breast or prostate cancer. Cheung et al., in a study on the effect of progressive muscle relaxation in cancer patients on reduction of anxiety signs and improvement of various domains of QoL in gastric cancer patients undergoing surgery, reported positive effects.[21] Kwekkeboom et al., in a study on the effect of two concurrent progressive muscle relaxation techniques and guided imagery on pain score of cancer patients, reported positive effects for both techniques.[22] Dehdari et al., investigating the effect of progressive muscle relaxation on QoL in cardiac patients after surgery, showed that this technique improved QoL in noncancer patients after surgery.[23] Results of the present study, in line with other studies, showed that scores of QoL in functional and overall domains were significantly different 6 weeks after intervention, compared to immediately after, revealing better effect of applying three concurrent techniques of progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, and deep diaphragmatic breathing. In progressive muscle relaxation, mind learns to concentrate on different body organs and be separated from the environment through this concentration, release and reduce muscular tension, and consequently, achieve peace and comfort. Beautiful and attractive pictures cause endorphins release in the body that leads to removal of stressful thoughts and achieving peace, and finally, feeling of euphoria. Diaphragmatic deep breathing provides the body with more oxygen. This technique, as a good respiration behavior, increases individuals’ ability to manage stress, especially physical tension. Based on the aforementioned explanations, all three techniques naturally lead to an improvement in QoL functional and overall domains.

Our results showed that mean scores of QoL functional and overall domains were not significantly different between study and control group before intervention, but immediately after and 6 weeks after, the difference was significant. Consistent with the present study, Yoo et al. reported that guided imagery and progressive muscle relaxation were effective on reduction of chemotherapy complications and improvement of QoL in cancer patients.[24] León-Pizarro et al. showed that relaxation generally improves QoL in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.[25]

Application of various and concurrent methods has a better effect, compared to applying each method alone. Sloman showed that progressive muscle relaxation and guided imagery had positive effects on depression of cancer patients. In their study, both techniques of relaxation and guided imagery were applied once separately and once concurrently in different groups. Results showed that the concurrent application of both techniques had a higher effect on QoL and depression of cancer patients.[26] The difference between the present study and their study is just application of concurrent three techniques of progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery and diaphragmatic deep breathing. On the other hand, application of a single complementary medicine method has yielded controversial results. Bordeleau et al. showed that relaxation practices had no effect on QoL of cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. In their study, the patients were intervened after chemotherapy, and the only method was relaxation.[27] Meanwhile, in the present study, not only three concurrent techniques were adopted, but also group education and having accompanying persons were among the differences between the present and other studies. Different socio-cultural contexts in different countries can affect people's behavior and reactions. Therefore, individuals’ responses to different relaxation techniques can be different, which needs further studies to be conducted in other countries.

Selection of the appropriate time to administrate these techniques is also important as Aswadi-Kermani et al. showed that relaxation had no effect on stress, anxiety and QoL of the patients undergoing chemotherapy as the complications of chemotherapy are so high that relaxation techniques have no effect on patients’ recovery and improvement of QoL.[28]

Hard work with older adults with cancer and their psychological and physical conditions in response to relaxation methods as well as their personal, psychological, and environmental differences and cultural level, their understanding from health, and consequently, their QoL scores, which might have affected our results, can be named as the limitations in the present study.

CONCLUSION

The results showed that progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, and deep diaphragmatic breathing are effective on improvement of QoL in breast or prostate cancer patients, and can be suggested as a cost-effective and convenient treatment. These methods can complete the main treatments and n relieve cancer patients and improve their QoL. As nurses can learn these techniques and apply them for their patients, holding related educational workshops to apply such complementary treatment methods for cancer patients recommend for the nurses.

Financial support and sponsorship

School of Nursing and Midwifery, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge to all study participants, nursing staffs in Seyed-Al-Shohada Medical Center. We also extend our gratitude to Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Newoton S, Hicky M, Marrs J. Oncology Nursing Advisor Comperhensive Guide to Clinical Practice. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noncommunicable Disease Profile. 2006. [Last accessed on 2014 Jul]. Available from: http://www.behdasht.gov.ir.pdf .

- 3.World Health organization. Noncommunicable Disease, Countries Profile. Geneva: WHO Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larrañaga N, Galceran J, Ardanaz E, Franch P, Navarro C, Sánchez MJ, et al. Prostate cancer incidence trends in Spain before and during the prostate-specific antigen era: Impact on mortality. Annals of Oncology. 2010;21(3):83. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larrañaga N, Galceran J, Ardanaz E, Franch P, Navarro C, Sánchez MJ, et al. Prostate cancer incidence trends in Spain before and during the prostate-specific antigen era: Impact on mortality. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 3 iii):83–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazovich D, Robien K, Cutler G, Virnig B, Sweeney C. Quality of life in a prospective cohort of elderly women with and without cancer. Cancer. 2009;115(18 Suppl):4283–97. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smeltzersc B. Brunner and Sudarth's Textbook of Medical-Surgical Nursing. 12th ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donavan KA, Thompson LM, Jacobsen PB. Handbook of Pain and Palliative Care. New York: Springer Publication; 2013. Pain, depression, and anxiety in cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ameli PJ, Bahadori M. Early detection of prostatic cancers. J Med Counc Islam Repub Iran. 1999;3:231–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Depiro NW. Help for the cancer patients. Patient Care. 2000;3:20–1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hickok JT, Roscoe JA, Morrow GR, Ryan JL. A phase II/III randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial of ginger (Zingiber officinale) for nausea caused by chemotherapy for cancer: A currently accruing URCC CCOP Cancer Control Study. Support Cancer Ther. 2007;4:247–50. doi: 10.3816/SCT.2007.n.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCann J. Therapies. 2th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waldspurger Robb WJ. Self-healing: A concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2006;41:60–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2006.00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwekkeboom KL, Cherwin CH, Lee JW, Wanta B. Mind-body treatments for the pain-fatigue-sleep disturbance symptom cluster in persons with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:1, 26–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molassiotis A, Yung HP, Yam BM, Chan FY, Mok TS. The effectiveness of progressive muscle relaxation training in managing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in Chinese breast cancer patients: A randomised controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 2002;10:237–46. doi: 10.1007/s00520-001-0329-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snyder M, Lindquist R. Complementary and Alternative Therapies in Nursing. 5th ed. New York: Springer Publication; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pine DS, Klein RG, Mannuzza S, Moulton JL, Jr, Lissek S, Guardino M, et al. Face-memory and emotion: Associations with major depression in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:1199–1208. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charalambous A. Integrative oncology in the Middle East: Role of traditional medicines in supportive cancer care, a conference of the Middle East Cancer Consortium. Eur J Integr Med. 2011;3:125–31. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Safaei A, Tabatabaei S. Reliability and validity of the QLQ-C30 questionnaire in cancer patients. Armaghan Danesh. 2007;12(2):79–87. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheung YL, Molassiotis A, Chang AM. The effect of progressive muscle relaxation training on anxiety and quality of life after stoma surgery in colorectal cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2003;12:254–66. doi: 10.1002/pon.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwekkeboom KL, Hau H, Wanta B, Bumpus M. Patients’ perceptions of the effectiveness of guided imagery and progressive muscle relaxation interventions used for cancer pain. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2008;14:185–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dehdari T, Heidarnia A, Ramezankhani A, Sadeghian S, Ghofranipour F. Effects of progressive muscular relaxation training on quality of life in anxious patients after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Indian J Med Res. 2009;129:603–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoo HJ, Ahn SH, Kim SB, Kim WK, Han OS. Efficacy of progressive muscle relaxation training and guided imagery in reducing chemotherapy side effects in patients with breast cancer and in improving their quality of life. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:826–33. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0806-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.León-Pizarro C, Gich I, Barthe E, Rovirosa A, Farrús B, Casas F, et al. A randomized trial of the effect of training in relaxation and guided imagery techniques in improving psychological and quality-of-life indices for gynecologic and breast brachytherapy patients. Psychooncology. 2007;16:971–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sloman R. Relaxation and imagery for anxiety and depression control in community patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2002;25:432–5. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200212000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bordeleau L, Szalai JP, Ennis M, Leszcz M, Speca M, Sela R, et al. Quality of life in a randomized trial of group psychosocial support in metastatic breast cancer: Overall effects of the intervention and an exploration of missing data. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1944–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aswadi-Kermani I, Harizchi Ghadim S, Piri E, Golchin R, Shanloei R, Sanaat Z. Effects of progressive relaxation technique on stress, anxiety and QOL of the patients undergoing chemotherapy as the complications of chemotherapy. Clin Psychol Psychiatr Iran (Thought and Behaviour) 2010;16:272. [Google Scholar]