Abstract

Objectives

To identify the core “domains” (i.e., patient outcomes, health-related conditions, or aspects of health) that relevant stakeholders agree are essential to assess in all clinical research studies evaluating the outcomes of acute respiratory failure survivors after hospital discharge.

Design

A two-round consensus process, using a modified Delphi methodology, with participants from 16 countries, including patient and caregiver representatives. Prior to voting, participants were asked to review: 1) results from surveys of clinical researchers, acute respiratory failure survivors, and caregivers, that rated the importance of 19 preliminary outcome domains, and 2) results from a qualitative study of acute respiratory failure survivors’ outcomes after hospital discharge, as related to the 19 preliminary outcome domains. Participants also were asked to suggest any additional potential domains for evaluation in the first Delphi survey.

Setting

Web-based surveys of participants representing 4 stakeholder groups relevant to clinical research evaluating post-discharge outcomes of acute respiratory failure survivors: clinical researchers, clinicians, patients and caregivers, and US federal research funding organizations.

Interventions

None.

Measurements and Main Results

Survey response rates were 97% and 99% in Round 1 and Round 2 respectively. There were 7 domains that met the a priori consensus criteria to be designated as core domains: physical function, cognition, mental health, survival, pulmonary function, pain, and muscle and/or nerve function.

Conclusion

This study generated a consensus-based list of core domains that should be assessed in all clinical research studies evaluating acute respiratory failure survivors after hospital discharge. Identifying appropriate measurement instruments to assess these core domains is an important next step toward developing a set of core outcome measures for this field of research.

Keywords: Patient Outcome Assessment, Follow-up studies, Intensive care, Disability Evaluation, Quality of Life, Clinical Trials

Introduction

Increasing intensive care unit (ICU) survival rates (1) and growing recognition that some ICU survivors experience new and long-lasting problems with their physical, cognitive, and mental health outcomes (2–5) highlight the diversity and magnitude of the challenges of ICU survivorship. In response, many groups, including the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI); Society of Critical Medicine; American Thoracic Society; and the Multi-society Task Force for Critical Care Research, have recommended prioritizing research on the outcomes of ICU survivors after hospital discharge (6–12). Although there have been >300 original research publications on ICU survivors’ outcomes after hospital discharge since 2000 (13), comparing, synthesizing, and interpreting this work has been difficult. (14) A recent scoping review found that 250 unique measurement instruments were used between 1970 and 2013 to assess ICU survivors’ outcomes after hospital discharge (13) making comparisons between studies difficult. Additionally, the psychometric properties of many of the instruments used in these studies have not been well-evaluated among ICU survivors.(15)

A core outcome set (COS) is a minimum collection of outcome measures reported in all studies within a specific field (16, 17). Importantly, a COS does not prevent investigators from collecting data on additional outcomes. Instead, a COS sets a minimum standard to ensure that the most basic and crucial outcomes in a given field are consistently assessed in the same way to facilitate comparisons, meta-analyses, and prevent bias from selective outcome reporting (18, 19). In developing a COS, relevant stakeholders participate in a deliberate and systematic process to identify measurement instruments that: 1) evaluate vitally important outcome domains, 2) have sound measurement properties, and 3) are accessible and feasible for the proposed purpose (20). As of September 2016, there are 7 projects registered with the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) Initiative (http://www.comet-initiative.org/) to develop COS related to critical care (21).

Before selecting measurement instruments for a COS there must be consensus on “Core Domains,” defined as patient outcomes, health-related conditions, or aspects of health, that are essential to evaluate within a clinical field (20, 22). The process of identifying Core Domains focuses on “what” types of outcomes to measure (e.g., muscle strength), before a subsequent step of determining “how” to measure these outcomes (e.g., hand grip dynamometry). Despite the hundreds of measurement instruments used to evaluate ICU survivors, it is likely that valid, reliable, and accessible instruments for measuring some core domains do not yet exist. However, focusing on those outcomes that are truly essential to evaluate in all clinical research studies of ICU survivors, regardless of current availability and feasibility, helps set long-term goals and identify methodologic research priorities within a field. Hence, our objective was to identify the Core Domains for clinical research evaluating the outcomes of survivors of acute respiratory failure (ARF), including acute respiratory distress syndrome, after hospital discharge using a rigorous consensus methodology and an international panel of relevant stakeholders.

Methods

We conducted a two-round, international consensus development process using a rigorous modified Delphi methodology with web-based communication and anonymous voting. The Delphi consensus methodology uses expert opinion to address questions for which empirical data are unavailable or inadequate (23). Recently, the Delphi method has been used to develop COS for research on conditions as diverse as multiple sclerosis (24), stroke (25), and preterm birth (26). More information about Delphi methodology, identifying outcome domains, and survey development is available in Table E1. We have reported this research study in accordance with current recommendations for establishing COS via the Delphi process (17, 27). A copy of the complete study protocol can be accessed at http://www.improvelto.com/. This project was registered with COMET Initiative (http://www.comet-initiative.org/studies/details/360) and funded by NHLBI (Grant R24HL111895, Improving Long-Term Outcomes Research for Acute Respiratory Failure – see www.ImproveLTO.com).

Recruitment of the Delphi Panel

We sought to recruit a diverse panel with emphasis on end-users of the COS (i.e., clinical researchers evaluating patient outcomes after ARF). Based on methodological guidance from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) (28), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (29), and Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) (20), four stakeholder groups relevant to clinical research evaluating post-discharge outcomes of acute respiratory failure survivors were identified for this consensus project: 1) critical care clinical researchers, 2) clinicians caring for ARF patients/survivors, 3) ICU survivors or caregivers of ICU survivors, and 4) representatives of federal organizations that fund ARF clinical research. Given that the target end users were clinical researchers, we focused on an international recruitment strategy, as described in Table E1 and E2 of the electronic supplementary materials. For recruiting clinicians, and patients and caregivers to the consensus process, we focused on representatives from the U.S., U.K., Australia, and Canada as these were the top 4 English-speaking countries represented in a scoping review of outcome measurement in ICU survivorship research (13) and participants will be asked to review individual English-language measurement instruments in a future study. Recruitment methods and response rates by stakeholder group, as well as the list of panel members are provided in Table E1 and Table E2. Invitation e-mails to all invited stakeholder representatives explained that survey completion would serve as informed consent and specified the need for commitment to, and timely participation in, the entire Delphi process. The Qualtrics online survey platform was used to collect demographic information about expert panel members, and DelphiManager software (COMET Initiative, Liverpool, UK) was used to administer the Round 1 and Round 2 surveys. The institutional review board of Johns Hopkins University approved this study.

Modified Delphi Methodology

At the start of both Delphi rounds, participants were reminded of the goal of the consensus project and the definition of a core domain. Each domain was rated using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) scale (30), which is a 9-point scale that is commonly divided into 3 categories for COS projects: Not Important (1 – 3), Important but Not Critical (4 – 6), and Critical (7 – 9). Additionally, panel members were provided an “Unable to Score” response and instructed to use it if they did not feel comfortable rating any specific domain. Consensus for designation as a “Core Domain” was defined a priori as: ≥70% of responses rating the domain as “Critical” (i.e., a score ≥7) and ≤15% of responses rating the domain as “Not Important” (i.e., score ≤3). This consensus definition has been used in other Delphi studies (31–34) and ensured that a domain would not achieve consensus if a minority stakeholder group (i.e. patients/caregivers or clinicians) commonly rated it as “Not Important”. All steps in the Delphi process took place on-line, and the anonymity of panel members was maintained throughout.

Round 1

Round 1 started January 8, 2016. Prior to voting, participants were asked to review: 1) results from surveys of clinical researchers, ARF survivors, and caregivers, that rated the importance of 19 preliminary outcome domains, and 2) results from a qualitative study of ARF survivors’ outcomes after hospital discharge, as related to the 19 preliminary outcome domains. The Round 1 survey asked Delphi panel members to rate the importance of each of the 19 preliminary domains without consideration of the availability, ease of use, feasibility, or measurement properties of any available instruments to assess the domain. Participants who scored the cognitive function domain as Critical (score ≥7) were then asked to rate the 9 cognitive function sub-domains, as described above. The survey asked an open-ended question about other potential core domain(s) missing from the preliminary list. Panel members were given the option to provide text-based comments or feedback after scoring each domain and at the end of the survey. To help prevent any potential bias from response order effects (i.e., primacy and recency effects(35)), the 19 preliminary domains were presented in one of four unique orders randomly generated using R statistical software (version 3.0.1; R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria). Panel members were asked to complete the Round 1 survey within 7 days of receipt and encouraged to contact the research team if any of the following were needed: clarification regarding the instructions, additional information about the Delphi process, technical support, or additional time to complete the survey. Panel members who had not responded after 7 days received up to three reminder e-mails, and after two weeks, non-respondents were contacted by phone or text message to encourage completion of the survey.

Round 2

All panel members were invited to complete the Round 2 survey regardless of Round 1 participation. The documents from Round 1 (as described above) were provided with Round 2. Within Round 2, histograms of ratings for each domain aggregated from all Round 1 participants, as well as stratified by each stakeholder group, were displayed. Participants who completed Round 1 also were shown their personal Round 1 rating alongside group ratings. The Round 2 survey asked participants to re-rate the 19 preliminary domains as well as 8 new domains proposed during Round 1, and the 9 cognitive subdomains. As in Round 1, panel members were instructed to rate the importance of each domain in Round 2 without consideration of the availability, ease of use, feasibility, or measurement properties of any available instruments to assess the domain. Panel members were asked to complete the Round 2 survey within 72 hours. Those who had not responded after 7 days received up to four reminder e-mails, and after two weeks non-respondents were contacted by phone or text message.

Statistical Reporting

Response rates were defined as the proportion of recruited panel members who completed each survey. Survey responses were summarized with descriptive statistics using SAS® version 9.4 (2013, Cary, NC).

Results

The expert panel had 77 participants, comprised of 35 (45%) clinical researchers, 19 (25%) clinicians and representatives of professional associations, 19 (25%) patients/caregivers, and 4 (5%) representatives of U.S. federal research funding organizations.(Table 1) There were 42 (55%) panel members from outside of the US, and 36 (47%) were female. The median years of professional experience (excluding patient and caregiver stakeholder group) was 14.5 (Interquartile range (IQR) 9 – 21).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Panel Members

| Characteristic | All Panel Members (n=77)a |

Clinical Researchers (n=35) |

Clinicians / Professional Assoc. (n=19) |

Patients and Caregivers (n=19)b |

US Federal Research Funding Organizations (n=4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, n (%) | |||||

| 25 – 44 | 31 (40%) | 14 (40%) | 7 (37%) | 9 (47%) | 1 (25%) |

| 45 – 64 | 43 (56%) | 21 (60%) | 12 (63%) | 7 (37%) | 3 (75%) |

| ≥65 | 3 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (16%) | 0 (0%) |

| Female, n (%) | 36 (47%) | 11 (31%) | 12 (63%) | 10 (53%) | 3 (75%) |

| Years of education, median (IQR) | 20 (18 – 22) | 21 (19 – 22.5) | 20 (19 – 21) | 16 (15 – 18) | 22 (21 – 22) |

| Country of residence, n (%) | |||||

| United States | 35 (45%) | 8 (23%) | 10 (53%) | 13 (68%) | 4 (100%) |

| Canada, United Kingdom, and Australia | 28 (37%) | 13 (37%) | 9 (47%) | 6 (32%) | 0 (0%) |

| Otherc | 14 (18%) | 14 (40%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Professional interest in critical illness, n (%)d | |||||

| Research – Clinical | 51 (66%) | 35 (100%) | 15 (79%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) |

| Research – Basic or translational | 16 (21%) | 11 (31%) | 4 (21%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) |

| Clinical work | 44 (57%) | 23 (66%) | 18 (95%) | 2 (11%) | 1 (25%) |

| None of the above | 19 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 17 (89%) | 2 (50%) |

| Years of professional experience, median (IQR)e | 14.5 (9 – 21) | 13 (9.5 – 19.5) | 17 (9.5 – 21) | NA | 18.5g |

| Area of professional expertise, n (%)d | |||||

| Physical health and functioning | 42 (55%) | 27 (77%) | 13 (68%) | NA | 1 (25%) |

| Mental health | 17 (22%) | 12 (34%) | 4 (21%) | NA | 0 (0%) |

| Cognitive function | 17 (22%) | 11 (31%) | 6 (32%) | NA | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 8 (10%) | 4 (11%) | 3 (16%) | NA | 1 (25%) |

| None | 8 (10%) | 3 (9%) | 3 (16%) | NA | 1 (25%) |

| Clinical work: Type of training, n (%)f | |||||

| Physician – Critical Care | 25 (57%) | 20 (87%) | 5 (28%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) |

| Physical, Occupational, or Respiratory Therapist and/or Speech Language Pathologist |

12 (27%) | 6 (26%) | 7 (39%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Nurse or Nurse Practitioner | 6 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (22%) | 2 (11%) | 0 (0%) |

| Physician – Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other clinical training | 4 (9%) | 3 (13%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Abbreviations: IQR, Inter-quartile Range; Assoc, Association

One panel member represented Clinical Researcher and Clinician/Professional association groups; total number of survey respondents n=76.

A patient caregiver was replaced by another patient caregiver member after round 2. Data from both panel members presented (patients n= 10, Caregivers n = 9).

Other countries: Singapore = 1, China = 1, Brazil = 1, Panama = 1, France = 2, Germany = 1, Belgium = 1, Greece = 1, Netherlands = 1, Norway = 1, Italy = 1, Ireland = 1

Panel members could select >1 response

All panel members from the Clinical Researcher, Clinicians /Professional Associations, and U.S. Federal Research Funding Organizations (n=58) provided data

44 (57%) panel members selected Clinical training, 5 of which selected 2 types of clinical work. Other clinical training includes Anesthesiology = 2, Internal medicine = 1, Pharmacy = 1.

Two funding body representatives responded and reported 14 and 23 years of professional experience.

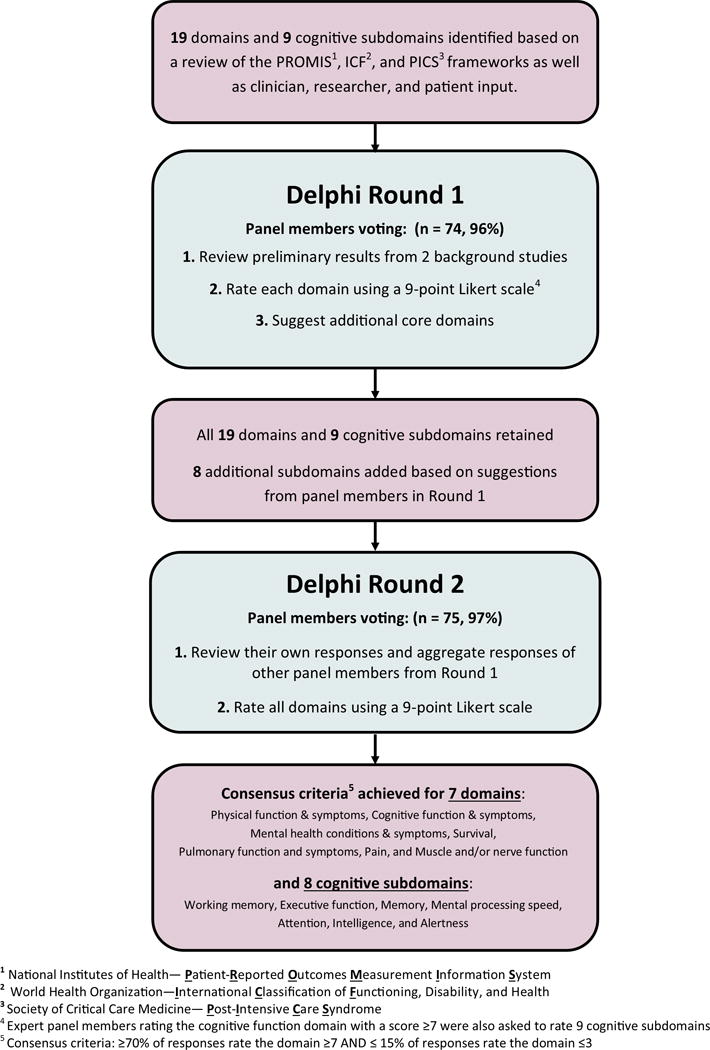

In Round 1, 74 of 76 panel members (97%) responded, with non-response from 2 clinical researchers. Among the 19 outcome domains provided, 7 (37%) met consensus criteria as Core Domains: physical function, cognition, mental health, survival, pulmonary function, pain, and muscle and/or nerve function.(Table 2) Support for individual domains was similar across stakeholder groups except 2 domains that had substantially higher support from patients/caregivers vs. other stakeholder groups: financial impact on the patient (78% vs. 38%), and healthcare resource utilization (67% vs. 41%). Conversely, the domain of survival was rated as “Critical” by 94% of clinical researchers and only 50% of patients/caregivers. Among the 9 cognitive sub-domains, 7 (78%) met the consensus criteria. (Table 4) Panel members suggested 8 additional domains for consideration in Round 2: fatigability/endurance, susceptibility to repeated infections, renal function, self-efficacy/management, management of complex medication regimens, resilience, hearing, and loss of taste.(Figure 1)

Table 2.

Round 1 Survey Results by Stakeholder Group

| Domain | Score | Proportion of stakeholders rating the domain ≥7 on a 9-point Likert scale | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Mean (SD) (n=74) |

All Panel Members (n=74) |

Clinical Researchers (n=33) |

Clinicians / Professional Associations (n=19) |

Patients and Caregivers (n=18) |

US Federal Research Funding Organizations (n=4) |

|

| Domains meeting consensus criteriaa | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Cognitive function and symptoms | 8.1 (1.1) | 68 (92%) | 32 (97%) | 18 (95%) | 14 (78%) | 4 (100%) |

| Physical function and symptoms | 8.1 (1.0) | 66 (89%) | 30 (91%) | 17 (89%) | 15 (83%) | 4 (100%) |

| Mental health conditions and symptoms | 7.9 (1.0) | 64 (86%) | 30 (91%) | 16 (84%) | 14 (78%) | 4 (100%) |

| Survival | 7.9 (1.6) | 56 (76%) | 31 (94%) | 14 (74%) | 9 (50%) | 2 (50%) |

| Pain | 7.2 (1.5) | 54 (73%) | 23 (70%) | 15 (79%) | 13 (72%) | 3 (75%) |

| Muscle and/or nerve function | 7.3 (1.5) | 52 (70%) | 23 (70%) | 12 (63%) | 13 (72%) | 4 (100%) |

| Pulmonary function and symptoms | 7 (1.6) | 52 (70%) | 20 (61%) | 14 (74%) | 15 (83%) | 3 (75%) |

|

| ||||||

| Domains not meeting consensus criteriaa | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Satisfaction with life, or personal enjoyment | 7.1 (1.4) | 51 (69%) | 21 (64%) | 14 (74%) | 14 (78%) | 2 (50%) |

| Return to work or prior activities | 6.9 (1.6) | 45 (61%) | 24 (73%) | 11 (58%) | 8 (44%) | 2 (50%) |

| Fatigue | 6.8 (1.7) | 44 (59%) | 20 (61%) | 11 (58%) | 11 (61%) | 2 (50%) |

| Impact on family and/or caregivers | 6.7 (1.7) | 40 (54%) | 17 (52%) | 11 (58%) | 11 (61%) | 1 (25%) |

| Swallowing function and symptoms | 6.4 (1.8) | 37 (50%) | 15 (45%) | 9 (47%) | 11 (61%) | 2 (50%) |

| Financial impact on patient | 6.2 (1.9) | 35 (47%) | 13 (39%) | 7 (37%) | 14 (78%) | 1 (25%) |

| Healthcare resource utilization | 6.3 (1.7) | 35 (47%) | 16 (48%) | 5 (26%) | 12 (67%) | 2 (50%) |

| Sleep function and symptoms | 6.3 (1.6) | 35 (47%) | 16 (48%) | 7 (37%) | 10 (56%) | 2 (50%) |

| Social roles, activities or relationships | 6.3 (1.8) | 34 (46%) | 17 (52%) | 7 (37%) | 9 (50%) | 1 (25%) |

| Type of residence | 6.2 (1.8) | 32 (43%) | 13 (39%) | 10 (53%) | 8 (44%) | 1 (25%) |

| Gastrointestinal function and symptoms | 5.5 (1.8) | 21 (28%) | 7 (21%) | 5 (26%) | 7 (39%) | 2 (50%) |

| Sexual function and symptoms | 4.8 (1.8) | 11 (15%) | 3 (9%) | 2 (11%) | 5 (28%) | 1 (25%) |

Abbreviations: SD, Standard Deviation

The consensus criteria for inclusion as a core domain was defined as ≥70% of all panel members rating a domain ≥7 and no more than 15% rating the domain ≤3 on a 9-point scale. Domains are ordered by the proportion of panel members rating the domain ≥7.

A total of 7 of 74 (9%) unique panel members ever selected “Unable to Score.” The number of panel members selecting “Unable to Score” by domain: Physical function and symptoms (1), Mental health conditions and symptoms (1), Survival (3), Muscle and/or nerve function (1), Pulmonary function and symptoms (1), Return to work or prior activities (3), Impact on family and/or caregivers (3), Swallowing function and symptoms (2), Healthcare resource utilization (1), Sleep function and symptoms (1), and Social roles, activities or relationships (1).

Table 4.

Results for Cognitive Subdomains by Stakeholder Group

| Score | Proportion of stakeholders scoring the domain ≥7 on a 9-point Likert scalea | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Subdomain | Mean (SD) | All Panel Membersb | Clinical Researchers | Clinicians / Professional Associations | Patients and Caregivers | US Federal Research Funding Organizations |

| ROUND 1 | ||||||

| Domains meeting consensus criteriaa | (n=74) | (n=74) | (n=33) | (n=19) | (n=18) | (n=4) |

|

| ||||||

| Working memory | 8.0 (1.0) | 60 (81%) | 28 (85%) | 16 (84%) | 12 (67%) | 4 (100%) |

| Executive function | 8.1 (1.0) | 58 (78%) | 26 (79%) | 16 (84%) | 12 (67%) | 4 (100%) |

| Memory | 8.0 (1.0) | 58 (78%) | 24 (73%) | 18 (95%) | 12 (67%) | 4 (100%) |

| Mental processing speed | 7.6 (1.2) | 56 (76%) | 27 (82%) | 13 (68%) | 12 (67%) | 4 (100%) |

| Attention | 7.8 (1.2) | 54 (73%) | 28 (85%) | 12 (63%) | 10 (56%) | 4 (100%) |

| Intelligence | 7.6 (1.3) | 54 (73%) | 27 (82%) | 12 (63%) | 12 (67%) | 3 (75%) |

| Alertness | 7.5 (1.3) | 52 (70%) | 22 (67%) | 15 (79%) | 12 (67%) | 3 (75%) |

|

| ||||||

| Core domain consensus criteria: ≥70% of all stakeholders rating the domain ≥7 | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Language / Verbal fluency / Naming | 7.5 (1.4) | 50 (68%) | 25 (76%) | 11 (58%) | 11 (61%) | 3 (75%) |

| Visuospatial ability or construction | 7.0 (1.5) | 42 (57%) | 20 (61%) | 10 (53%) | 10 (56%) | 2 (50%) |

|

| ||||||

| ROUND 2 | ||||||

| Domains meeting consensus criteriaa | (n=75) | (n=75) | (n=35) | (n=19) | (n=17) | (n=4) |

|

| ||||||

| Working memory | 8.3 (0.8) | 72 (96%) | 34 (97%) | 18 (95%) | 16 (94%) | 4 (100%) |

| Memory | 8.3 (0.9) | 70 (93%) | 33 (94%) | 18 (95%) | 15 (88%) | 4 (100%) |

| Mental processing speed | 8.2 (0.9) | 69 (92%) | 34 (97%) | 15 (79%) | 16 (94%) | 4 (100%) |

| Executive Function | 7.8 (0.9) | 69 (92%) | 33 (94%) | 18 (95%) | 14 (82%) | 4 (100%) |

| Attention | 7.9 (1.1) | 65 (87%) | 33 (94%) | 15 (79%) | 13 (76%) | 4 (100%) |

| Intelligence | 7.8 (1.1) | 63 (84%) | 32 (91%) | 15 (79%) | 12 (71%) | 4 (100%) |

| Alertness | 7.4 (1.0) | 62 (83%) | 29 (83%) | 15 (79%) | 14 (82%) | 4 (100%) |

| Language / Verbal Fluency / Naming | 7.7 (1.2) | 59 (79%) | 31 (89%) | 12 (63%) | 13 (76%) | 3 (75%) |

|

| ||||||

| Core domain consensus criteria: ≥70% of all stakeholders rating the domain ≥7 | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Visuospatial Ability or Construction | 7.1 (1.2) | 51 (68%) | 25 (71%) | 10 (53%) | 13 (76%) | 3 (75%) |

Abbreviations: SD, Standard Deviation

The consensus criteria for inclusion as a core domain was defined as ≥70% of all panel members rating a domain ≥7 and no more than 15% rating the domain ≤3 on a 9-point scale. Domains are ordered by the proportion of panel members rating the domain ≥7.

In Round 1 a total of 13 of 74 (18%) unique panel members ever selected “Unable to Score”. Number of panel members selecting “Unable to Score” by domain: Working memory (8), Executive function (10), Memory (10), Mental processing speed (6), Attention (8), Intelligence (6), Alertness (8), Language/Verbal fluency/Naming (7), and Visuospatial ability or construction (7). In Round 2 a total of 3 of 75 (4%) unique panel members ever selected “Unable to Score”. Number of panel members selecting “Unable to Score” by domain: Working memory (1), Memory (1), Mental processing speed (1), Executive function (1), Attention (1), Intelligence (1), Alertness (1), Language/Verbal fluency/Naming (1), and Visuospatial ability or construction (1).

Figure 1. Modified Delphi Process Flow Diagram.

1National Institutes of Health – Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

2World Health Organization – International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health

3Society of Critical Care Medicine – Post-Intensive Care Syndrome

4Expert panel members rating the cognitive function domain with a score ≥7 were also asked to rate 9 cognitive subdomains

5Consensus criteria: ≥70% of responses rate the domain ≥7 and ≤15% of responses rate the domain ≤3

The results of Round 2 are summarized in Tables 3 and 4. The overall response rate was 99% (75 of 76), with 1 patient/caregiver not responding. Each of the 7 domains meeting consensus criteria in Round 1 were rated as Critical (score ≥7) by even larger proportions of the panel in Round 2. None of the 8 additional domains suggested by panel members in Round 1 met the consensus criteria. Among the 9 cognitive sub-domains, 8 (89%) met the consensus criteria, with all cognitive subdomains receiving similar levels of support and 13 (18%) of panel members selecting “Unable to score” for at least one domain. (Table 4) Patients/caregivers (vs. other stakeholder groups) continued to more strongly rate two domains as “Critical” for inclusion: financial impact on the patient (88% vs. 48%), and healthcare resource utilization (71% vs. 50%). However, with only 57% and 55%, respectively, of all panel members rating these domains as “Critical,” they did not meet the consensus criteria as Core Domains. As in Round 1, support for the survival domain remained much greater among clinical researchers (100%) than patients/caregivers (59%). The distributions of responses for each domain in Round 2 are displayed in Table E3.

Table 3.

Round 2 Survey Results by Stakeholder Group

| Domain | Score | Proportion of stakeholders scoring the domain ≥7 on a 9-point Likert scale | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Mean (SD) (n=75) |

All Panel Members (n=75) |

Clinical Researchers (n=35) |

Clinicians / Professional Associations (n=19) |

Patients and Caregivers (n=17) |

US Federal Research Funding Organizations (n=4) |

|

| Domains meeting consensus criteriaa | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Physical function and symptoms | 8.4 (0.8) | 73 (97%) | 34 (97%) | 18 (95%) | 17 (100%) | 4 (100%) |

| Cognitive function and symptoms | 8.4 (0.9) | 71 (95%) | 34 (97%) | 18 (95%) | 15 (88%) | 4 (100%) |

| Mental health conditions and symptoms | 8.0 (0.8) | 70 (93%) | 33 (94%) | 18 (95%) | 15 (88%) | 4 (100%) |

| Survival | 8.2 (1.3) | 64 (85%) | 35 (100%) | 16 (84%) | 10 (59%) | 3 (75%) |

| Pulmonary function and symptoms | 7.3 (1.4) | 64 (85%) | 29 (83%) | 14 (74%) | 17 (100%) | 4 (100%) |

| Pain | 7.5 (1.1) | 63 (84%) | 29 (83%) | 17 (89%) | 14 (82%) | 3 (75%) |

| Muscle and/or nerve function | 7.3 (1.2) | 62 (83%) | 27 (77%) | 16 (84%) | 15 (88%) | 4 (100%) |

|

| ||||||

| Domains not meeting consensus criteriaa | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Satisfaction with life, or personal enjoyment | 7.2 (1.2) | 52 (69%) | 22 (63%) | 14 (74%) | 14 (82%) | 2 (50%) |

| Impact on family and/or caregivers | 7.1 (1.4) | 50 (67%) | 23 (66%) | 12 (63%) | 13 (76%) | 2 (50%) |

| Fatigue | 6.9 (1.4) | 49 (65%) | 23 (66%) | 12 (63%) | 12 (71%) | 2 (50%) |

| Return to work or prior activities | 7.0 (1.3) | 48 (64%) | 23 (66%) | 13 (68%) | 10 (59%) | 2 (50%) |

| Swallowing function and symptoms | 6.7 (1.6) | 47 (63%) | 20 (57%) | 11 (58%) | 13 (76%) | 3 (75%) |

| Financial impact on patient | 6.7 (1.5) | 43 (57%) | 19 (54%) | 8 (42%) | 15 (88%) | 1 (25%) |

| Healthcare resource utilization | 6.6(1.2) | 41 (55%) | 20 (57%) | 7 (37%) | 12 (71%) | 2 (50%) |

| Sleep function and symptoms | 6.4 (1.4) | 38 (51%) | 17 (49%) | 7 (37%) | 12 (71%) | 2 (50%) |

| Social roles, activities or relationships | 6.6 (1.3) | 37 (49%) | 19 (54%) | 6 (32%) | 11 (65%) | 1 (25%) |

| Type of residence | 6.3 (1.6) | 30 (40%) | 12 (34%) | 9 (47%) | 8 (47%) | 1 (25%) |

| Gastrointestinal function and symptoms | 5.5 (1.5) | 16 (21%) | 4 (11%) | 5 (26%) | 6 (35%) | 1 (25%) |

| Sexual function and symptoms | 4.9 (1.2) | 7 (9%) | 3 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (24%) | 0 (0%) |

|

| ||||||

| Domains suggested by stakeholders during Round 1 (none meeting consensus criteriaa) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Fatigability / endurance | 6.9 (1.4) | 47 (63%) | 19 (54%) | 12 (63%) | 14 (82%) | 2 (50%) |

| Susceptibility to repeated infections | 6.7 (1.5) | 46 (61%) | 17 (49%) | 12 (63%) | 14 (82%) | 3 (75%) |

| Renal Function | 6.5 (1.5) | 42 (56%) | 17 (49%) | 9 (47%) | 14 (82%) | 2 (50%) |

| Self-efficacy/management | 6.4 (1.7) | 36 (48%) | 16 (46%) | 7 (37%) | 10 (59%) | 3 (75%) |

| Management of Complex Medication Regimens | 6.2 (1.7) | 35 (47%) | 13 (37%) | 10 (53%) | 11 (65%) | 1 (25%) |

| Resilience | 6.4 (1.7) | 34 (45%) | 14 (40%) | 6 (32%) | 12 (71%) | 2 (50%) |

| Hearing | 5.8 (1.6) | 23 (31%) | 14 (40%) | 3 (16%) | 3 (18%) | 3 (75%) |

| Loss of Taste | 5.6 (1.6) | 18 (24%) | 10 (29%) | 3 (16%) | 4 (24%) | 1 (25%) |

Abbreviations: SD, Standard Deviation

The consensus criteria for inclusion as a core domain was defined as ≥70% of all panel members rating a domain ≥7 and no more than 15% rating the domain ≤3 on a 9-point scale. Domains are ordered by the proportion of panel members rating the domain ≥7.

Discussion

This study used a two-round, modified Delphi consensus methodology with an international panel of 77 stakeholders to identify core domains for clinical research evaluating post-discharge outcomes of ARF survivors. The panel considered a preliminary list of 19 outcome domains, suggested 8 additional domains for consideration, and ultimately reached the a priori consensus criteria for 7 domains. Participation and retention of all stakeholder groups was excellent across both Delphi rounds.

Core domains are defined as patient outcomes, health-related conditions, or aspects of health, that are essential to evaluate within a specific field of research (20, 22). Notably, the “essential” nature of core domains may vary by stakeholder group. Hence, assembling a consensus panel requires careful consideration. Clinical trials seek to assess the efficacy of interventions so that evidence-based treatment decisions can be made for individual patients. Current guidelines recommend that these treatment decisions be shared by patients, their families, and their clinicians (36), making them the ultimate end-users of research. However, the potential benefits of many COS have not been realized because the COS was not widely adopted by clinical researchers who perform trials (37, 38). Unless research funders and journal editors require the use of COS, clinical researchers may not fully embrace them. Thus, to be successful, a COS must address outcomes that clinical researchers and their funders believe are important and that assist patients, their families, and clinicians in clinical decision-making (39). We chose to include representatives from each of these stakeholder groups in our expert panel.

A recent systematic review of studies to achieve consensus on domains for COS found that only 16% of studies involved patients or caregivers in the consensus process (40). An even smaller subset of these studies permitted patients or caregivers to participate in the prioritization of outcomes. The public is commonly excluded from Delphi panels because it can be challenging to identify appropriate patient and caregiver representatives, provide them with information tailored to their health literacy level, and incorporate them into the consensus process in a way that effectively utilizes and respects their area of expertise(41–43). We purposefully recruited a sufficient number of patient/caregiver representatives to ensure that if the most patient/caregivers rated a domain as “Not Important” (score ≤3) the domain would not meet our a priori consensus criteria, effectively giving patients and caregivers veto power. Clinicians and professional association representatives also had similar veto power given the size of their membership on the panel.

Stakeholder groups rated the vast majority of domains similarly. The 3 notable exceptions were the domains of financial impact on patients, healthcare resource utilization, and survival. These differences likely reflect distinct stakeholders’ perspectives. After hospital discharge, ARF survivors experience high rates of hospital readmission and unemployment(2, 44) creating a direct financial burden for patients and caregivers. Similarly, clinical researchers were likely aware of mortality as a competing risk in evaluating functional outcomes (45, 46) and thus, universally viewed survival as essential whereas all caregivers on the panel had family members who were still alive years after ARF. Additional research is needed to determine whether the outcomes prioritized by caregivers of living ARF survivors differ from those of caregivers to ARF “survivors” who subsequently died shortly hospital discharge.

The 7 core domains identified in this study encompass aspects of physical, mental, and cognitive health. Notably, there were no core domains within social health (20, 47). This might reflect an assumption that social health is largely determined by physical, cognitive, and mental health. However, the domain “Satisfaction with life, or personal enjoyment”, which was rated as “Critical” by 69% of all panel members, including 82% of patients and caregivers, may reflect some aspects of social health. Notably, in previous pilot testing conducted before starting this project, the domain “health related quality of life” received strong support (48) as a core domain, but many clinical researchers struggled to conceptualize this domain separate from its most well-known measurement instruments. Thus, we re-named the domain, which may have resulted in lower ratings among clinical researchers (vs. patients/caregivers). Consistent with prior expert groups (6, 9, 48), we believe it is important to include a measure addressing survivors’ subjective quality of life in a COS. We also encourage clinical researchers to consider assessing outcome domains that failed to meet the criteria for inclusion in a COS, but were rated as critical by the vast majority of patient and caregiver representatives, such as financial impact on patients (88%) and impact on family and/or caregivers (76%).

Limiting invitations to representatives of U.S. federal research funding organizations combined with the 50% recruitment rate of these organizations represents a limitation of this study. After consultation with their internal ethics advisors, three-quarters of the non-participating federal organizations believed that participating in this NIH-funded research represented a conflict of interest. However, COS may be less likely to be adopted if research funders do not endorse and enforce them, making funder input into COS development desirable. We also cannot determine how our results would have differed if the Delphi panel had included patient and caregiver representatives from countries other than the four major English-speaking countries included in this project.

In conclusion, research evaluating post-discharge outcomes of ARF survivors has flourished without any deliberate effort to standardize the outcome domains assessed or the measurement instruments used. Via a rigorous modified Delphi process, an international panel of clinical researchers, clinicians, patients and caregivers, and US federal research funding organizations reached consensus on the following 7 core domains for clinical research evaluating post-discharge outcomes of ARF survivors: physical function, cognition, mental health, survival, pulmonary function, pain, and muscle and/or nerve function. These 7 domains should always be measured in this field of research. The next step is achieving consensus on what measurement instruments should be used to assess these core domains.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Wesley Davis for assistance with survey development, Paula Williamson for methodological advice, and Bronagh Blackwood and John Marshall for assistance with recruitment of stakeholder representatives.

Funding Support: This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [R24HL111895]. Dr. Bingham also receives support through a Methods Award from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI, SC14-11402-10918) and the Rheumatic Diseases Research Core Center Human Subjects Core funded by the National Institutes of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIH P30-AR053503).

Footnotes

Copyright form disclosure: All authors received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Turnbull’s institution received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Dr. Needham’s institution received funding from the NIH/NHLBI, Gordon & Betty Moore Foundation, NIH, and NHMRC (Australia).

References

- 1.Zimmerman JE, Kramer AA, Knaus WA. Changes in hospital mortality for United States intensive care unit admissions from 1988 to 2012. Crit Care Lond Engl. 2013;17:R81. doi: 10.1186/cc12695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, et al. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:683–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan E, Dowdy DW, Colantuoni E, et al. Physical complications in acute lung injury survivors: a two-year longitudinal prospective study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:849–859. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1306–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang M, Parker AM, Bienvenu OJ, et al. Psychiatric Symptoms in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Survivors: A 1-Year National Multicenter Study. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:954–965. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angus DC, Carlet J. 2002 Brussels Roundtable Participants: Surviving intensive care: a report from the 2002 Brussels Roundtable. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:368–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1624-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angus DC, Mira J-P, Vincent J-L. Improving clinical trials in the critically ill. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:527–532. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c0259d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spragg RG, Bernard GR, Checkley W, et al. Beyond mortality: future clinical research in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:1121–1127. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0024WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lieu TA, Au D, Krishnan JA, et al. Comparative effectiveness research in lung diseases and sleep disorders: recommendations from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:848–856. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0634WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:502–509. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deutschman CS, Ahrens T, Cairns CB, et al. Multisociety task force for critical care research: key issues and recommendations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:96–102. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201110-1848ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carson SS, Goss CH, Patel SR, et al. An Official American Thoracic Society Research Statement: Comparative Effectiveness Research in Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201310-1790ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turnbull AE, Rabiee A, Davis WE, et al. Outcome Measurement in ICU Survivorship Research From 1970 to 2013: A Scoping Review of 425 Publications. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1267–1277. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Needham DM. Understanding and improving clinical trial outcome measures in acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:875–877. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0362ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson KA, Davis WE, Dinglas VD, et al. A systematic review finds limited data on measurement properties of instruments measuring outcomes in adult intensive care unit survivors. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke M. Standardising outcomes for clinical trials and systematic reviews. Trials. 2007;8:39. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, et al. Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials: issues to consider. Trials. 2012;13:132. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dwan K, Altman DG, Arnaiz JA, et al. Systematic Review of the Empirical Evidence of Study Publication Bias and Outcome Reporting Bias. PLOS ONE. 2008;3:e3081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirkham JJ, Dwan KM, Altman DG, et al. The impact of outcome reporting bias in randomised controlled trials on a cohort of systematic reviews. BMJ. 2010;340:c365. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boers M, Kirwan JK, Tugwell PT, et al. OMERACT Handbook. Ottowa, ON, Canada: 2015. OMERACT Handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Search Results: Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials Initiative (COMET) [Internet] 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.06.007. [cited 2016 Sep 11] Available from: http://www.comet-initiative.org/studies/searchresults?guid=79a21fb5-4236-45a5-a63c-0db9398351a0. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Boers M, Kirwan JR, Wells G, et al. Developing core outcome measurement sets for clinical trials: OMERACT filter 2.0. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:745–753. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dalkey N, Helmer O. An Experimental Application of the DELPHI Method to the Use of Experts. Manag Sci. 1963;9:458–467. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan F, Pallant JF. Use of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) to identify preliminary comprehensive and brief core sets for multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:205–213. doi: 10.1080/09638280600756141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salinas J, Sprinkhuizen SM, Ackerson T, et al. An International Standard Set of Patient-Centered Outcome Measures After Stroke. Stroke. 2015 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010898. STROKEAHA.115.010898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van ʼt Hooft J, Duffy JMN, Daly M, et al. A Core Outcome Set for Evaluation of Interventions to Prevent Preterm Birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:49–58. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirkham JJ, Gorst S, Altman DG, et al. Core Outcome Set–STAndards for Reporting: The COS-STAR Statement. PLOS Med. 2016;13:e1002148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.PCORI’s Stakeholders | PCORI [Internet] [cited 2016 Sep 8]] Available from: http://www.pcori.org/funding-opportunities/what-we-mean-engagement/pcoris-stakeholders.

- 29.The Effective Health Care Program Stakeholder Guide -Chapter 3 [Internet] 2014 [cited 2016 Sep 8] Available from: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/evidence-based-reports/stakeholderguide/index.html.

- 30.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008;336:995–998. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39490.551019.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bartlett SJ, Hewlett S, Bingham CO, et al. Identifying core domains to assess flare in rheumatoid arthritis: an OMERACT international patient and provider combined Delphi consensus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1855–1860. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanekom S, Van Aswegen H, Plani N, et al. Developing minimum clinical standards for physiotherapy in South African intensive care units: the nominal group technique in action. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21:118–127. doi: 10.1111/jep.12257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prinsen CAC, Vohra S, Rose MR, et al. How to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a “Core Outcome Set” – a practical guideline. Trials. 2016;17:449. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1555-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Response Order Effects [Internet] 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks California 91320 United States of America: Sage Publications, Inc; 2008. Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods. [cited 2016 Sep 17] Available from: http://methods.sagepub.com/reference/encyclopedia-of-survey-research-methods/n488.xml. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kon AA, Davidson JE, Morrison W, et al. Shared Decision-Making in Intensive Care Units. Executive Summary of the American College of Critical Care Medicine and American Thoracic Society Policy Statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:1334–1336. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0269ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mulla SM, Maqbool A, Sivananthan L, et al. Reporting of IMMPACT-recommended core outcome domains among trials assessing opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2015;156:1615–1619. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Copsey B, Hopewell S, Becker C, et al. Appraising the uptake and use of recommendations for a common outcome data set for clinical trials: a case study in fall injury prevention. Trials. 2016;17:131. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1259-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tunis SR, Clarke M, Gorst SL, et al. Improving the relevance and consistency of outcomes in comparative effectiveness research. J Comp Eff Res. 2016;5:193–205. doi: 10.2217/cer-2015-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gargon E, Gurung B, Medley N, et al. Choosing Important Health Outcomes for Comparative Effectiveness Research: A Systematic Review. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e99111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harman NL, Bruce IA, Kirkham JJ, et al. The Importance of Integration of Stakeholder Views in Core Outcome Set Development: Otitis Media with Effusion in Children with Cleft Palate. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0129514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turnbull AE, Sahetya SK, Needham DM. Aligning critical care interventions with patient goals: A modified Delphi study [Internet] Heart Lung J Acute Crit Care. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2016.07.011. [cited 2016 Sep 15] Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S014795631630156X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Major ME, Kwakman R, Kho ME, et al. Surviving critical illness: what is next? An expert consensus statement on physical rehabilitation after hospital discharge. Crit Care. 2016;20:354. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1508-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruhl AP, Lord RK, Panek JA, et al. Health care resource use and costs of two-year survivors of acute lung injury. An observational cohort study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:392–401. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201409-422OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wolkewitz M, Cooper BS, Bonten MJM, et al. Interpreting and comparing risks in the presence of competing events. BMJ. 2014;349:g5060. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Walraven C, McAlister FA. Competing risk bias was common in Kaplan–Meier risk estimates published in prominent medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:170–173.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hodgson CL, Turnbull AE, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Clinician and researcher perspectives on core domains in evaluating post-discharge patient outcomes after acute respiratory failure. Phys Ther J. 2016 doi: 10.2522/ptj.20160196. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.