Abstract

Rit is one of the original members of a novel Ras GTPase subfamily that uses distinct effector pathways to transform NIH 3T3 cells and induce pheochromocytoma cell (PC6) differentiation. In this study, we find that stimulation of PC6 cells by growth factors, including nerve growth factor (NGF), results in rapid and prolonged Rit activation. Ectopic expression of active Rit promotes PC6 neurite outgrowth that is morphologically distinct from that promoted by oncogenic Ras (evidenced by increased neurite branching) and stimulates activation of both the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling pathways. Furthermore, Rit-induced differentiation is dependent upon both MAP kinase cascades, since MEK inhibition blocked Rit-induced neurite outgrowth, while p38 blockade inhibited neurite elongation and branching but not neurite initiation. Surprisingly, while Rit was unable to stimulate ERK activity in NIH 3T3 cells, it potently activated ERK in PC6 cells. This cell type specificity is explained by the finding that Rit was unable to activate C-Raf, while it bound and stimulated the neuronal Raf isoform, B-Raf. Importantly, selective down-regulation of Rit gene expression in PC6 cells significantly altered NGF-dependent MAP kinase cascade responses, inhibiting both p38 and ERK kinase activation. Moreover, the ability of NGF to promote neuronal differentiation was attenuated by Rit knockdown. Thus, Rit is implicated in a novel pathway of neuronal development and regeneration by coupling specific trophic factor signals to sustained activation of the B-Raf/ERK and p38 MAP kinase cascades.

Members of the Ras subfamily of GTP-binding proteins are intracellular signaling molecules that mediate a wide variety of cellular functions, including proliferation, cell survival, and differentiation (64). The Ras subfamily consists of more than 35 highly conserved proteins, including the classical Ras proteins (H-Ras, N-Ras, and K-Ras), R-Ras, TC21, Rap1, Rheb, RalA, and the newest members of the family, Rit, Rin, and Ric (45). As molecular switches, the Ras-related proteins respond to external signals by exchanging GTP for bound GDP, and the GTP-bound active proteins interact with a variety of cellular effector proteins, thereby channeling externally derived signals from a repertoire of cell surface receptors to specific intracellular signaling cascades (6).

A large body of work has defined a critical role for the classical Ras proteins in the processes of cell growth and differentiation (6), while other members of the subfamily have been shown to be oncogenically activated in human tumors and to possess the ability to transform rodent fibroblasts in culture. These proteins include the classical Ras proteins (H-Ras, N-Ras, and K-Ras) (4), R-Ras (50), TC21 (7), and R-Ras3/M-Ras (28, 34). However, it is now clear that members of the wider Ras-related protein family possess distinct biochemical and biological activities and express both overlapping and unique functions (45). We and others have previously described the cloning of Rit, a novel member of the Ras-related proteins (31, 56, 69). Although Rit shares more than 50% sequence identity with Ras and is expressed in a majority of embryonic and adult tissues and its GTP binding and hydrolysis activities have been confirmed (56), it shares a unique effector domain with the closely related Rin and Drosophila Ric proteins and lacks a known recognition site for C-terminal lipidation required for the association of Ras proteins with the cellular membranes (56). These similarities have generated speculation that like Ras, Rit might activate similar signal transduction pathways and regulate important aspects of growth control and motivated studies examining the ability of activated Rit mutants to regulate cell growth and oncogenic transformation (25, 49, 55, 56, 59). These studies have demonstrated that Rit signals to a variety of Ras-responsive elements and transforms NIH 3T3 cells to tumorigenicity, binds and activates RGL3, a novel RalGEF, to activate Ral GTPase signaling pathways but fails to activate the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), Jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK), p38, or phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt kinases in mouse fibroblasts, suggesting that Rit uses novel effector pathways to regulate proliferation, transformation, and differentiation.

The rat pheochromocytoma cell line PC12 has been used extensively as a model system to implicate multiple signaling pathways in nerve growth factor (NGF)-dependent neuronal survival and differentiation. NGF treatment of PC12 cells leads to their differentiation into a sympathetic-like neuronal cell phenotype characterized by neurite outgrowth (20). Previous studies have suggested that NGF-induced, sustained activation of the ERK mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathway is crucial for neuronal differentiation of these cells, since blockade of ERK activation inhibits neurite induction, while constitutive activation of the ERK pathway results in neurite outgrowth (11, 17). However, recent studies have suggested that both PI3K and p38 MAP kinase signaling pathways also participate in the NGF-induced differentiation of PC12 cells. NGF induces sustained activation of both of these signaling pathways, and selective blockade of either the p38 (36) or PI3K (30) signaling cascade results in inhibition of neurite outgrowth. Surprisingly, neurite outgrowth induced by the expression of constitutively active MEK, a recognized regulator of ERK activity, also depends in part on p38 activity, since MEK activates both ERK and p38 MAP kinases, and MEK-induced PC12 cell neurite outgrowth is sensitive to inhibition of p38 kinase by SB203580 (36). Thus, a well-balanced activation of the ERK and p38 MAP kinase pathways and PI3K signaling may be necessary for neuronal differentiation of PC12 cells in response to NGF. Consistent with these findings, we have previously reported that activated Rit stimulates the MEK/ERK pathway, but not PI3K signaling, in PC6 cells and supports neurite outgrowth and promotes cell survival (59). However, ERK MAP kinase activity was not found to be elevated in Rit-transformed NIH 3T3 cells (49, 51). Furthermore, despite sharing a highly conserved effector core region with Ras, no interaction was detected between wild-type Rit and C-Raf or B-Raf in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae two-hybrid system (56). Thus, questions concerning both the mechanism of Rit-dependent ERK activation and the signal transduction pathways mediating Rit-induced neuronal differentiation remain.

In the present study, we investigated the signaling pathways controlled by Rit during neurite elongation of PC6 cells. We demonstrate that activated Rit stimulates sustained activation of both p38 and ERK MAP kinase signaling pathways, but not the JNK, ERK5, or PI3K/Akt kinase cascades. Coimmunoprecipitation analysis shows that a constitutively activated Rit mutant (RitL79) is capable of robust association with the B-Raf serine-threonine kinase but only weakly bound C-Raf. In accordance with these data, we also observe the constitutive activation of the ERK MAP kinase cascade, including ERK1/2, MEK1/2, and B-Raf, but importantly, not C-Raf, in RitL79-transformed PC6 cells. Inhibition of MEK/ERK activity in PC6 cells expressing RitL79 inhibits neurite outgrowth, while inhibition of p38 MAP kinase signaling inhibited Rit-induced neurite elongation and branching but not neurite initiation. Furthermore, expression of dominant-negative B-Raf, but not dominant-negative C-Raf, inhibited both Rit-mediated neurite elongation and ERK activation. We have also explored the upstream signaling events leading to Rit activation and find that Rit is rapidly stimulated after exposing PC6 cells to epidermal growth factor (EGF) and NGF. To assess directly the contribution of Rit to NGF signaling pathways, we selectively inhibited the expression of Rit using small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated RNA interference (14-16). Inhibiting Rit expression in PC6 cells both potently inhibited NGF-mediated ERK and p38 MAP kinase activation and disrupted NGF-dependent neuronal differentiation. These observations establish Rit as a critical component of the cellular machinery that is involved in maintaining normal nervous system function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction and reagents.

The mammalian expression constructs containing human Rit or H-Ras and their mutants in N-terminal glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged vector pEBG (kindly provided by J. H. Kehrl, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health) or N-terminal triple-Flag-tagged vector p3xFLAG-CMV-10 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) were generated by PCR amplification. The recombinant adenovirus containing green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Ad-GFP), wild-type Rit (Ad-RitWT/GFP), constitutively active Rit-Q79L (Ad-RitL79/GFP) or constitutively active Ras-Q61L (Ad-RasL61) have been described previously (59). Hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged mammalian expression vector pcDNA3 constructs of wild-type B-Raf, the dominant-negative B-Raf mutant (B-RafAA in which both T598 and S601 were replaced by alanine), Flag-tagged full-length wild-type C-Raf, and a kinase-inactive C-Raf mutant (C-RafKD, in which T491 was replaced by glutamic acid and S494 was replaced by aspartic acid) were provided by K. L. Guan (University of Michigan) (78) and recloned into pEBG and pCMV-Myc (BD Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.).

The GST-RGL3-Ras binding domain (RBD) and GST-Raf-Ras interaction domain (RID) (1 to 140 amino acids) glutathione-agarose beads were prepared from bacterially expressed GST-RGL3-RBD and GST-Raf-RID as described previously (55). Anti-Flag and anti-ERK5 monoclonal antibodies were from Sigma. Phospho-ERK1/2 monoclonal (MAP kinase [MAPK] p44/42), phospho-MEK1/2 polyclonal, phospho-ERK5 polyclonal, phospho-p38 monoclonal, phospho-Akt (Ser473) polyclonal, p38 polyclonal, and Akt polyclonal antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, Mass.). MEK1 polyclonal, p42/44 MAPK/ERK polyclonal, B-Raf polyclonal, C-Raf (Raf-1) polyclonal, and actin goat polyclonal antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, Calif.). Phospho-specific Raf (Ser338) rat monoclonal antibody and Ras monoclonal antibodies were from Upstate Biotechnology, Inc. (Lake Placid, N.Y.). Phospho-specific JNK1/2 (pTpY183/185) polyclonal antibody was from Biosource (Camarillo, Calif.). Biotinylated anti-HA (12CA5), anti-Myc (9E10), and anti-Flag antibodies were generated using the Amersham protein biotinylation system (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) following the manufacturer's recommendations. The anti-Rit monoclonal (R0003U) and anti-Rin monoclonal (R0005U) antibodies have been described previously (59). Recombinant human EGF and rat β-NGF were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn.), while phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and A23187 were from Sigma.

Tissue culture, infection, and transfection.

PC6 is a subline of PC12 cells that produces neurites in response to NGF but also grows isolated cells, rather than clumps of cells (42) (generous gift of T. Vanaman, University of Kentucky, Lexington). The cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Life Technologies) containing 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Life Technologies), 5% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated horse serum (Life Technologies), 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, and 100 U of penicillin per ml at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. COS cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.) and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, and 100 U of penicillin per ml at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Recombinant adenoviruses were constructed by the Vogelstein method and purified by two rounds of CsCl gradient banding using ultracentrifugation (21) as described previously (59). Viral stock concentrations were determined by standard plaque assays. To infect PC6 cells, cells were seeded at either 10,000 cells/cm2 (for neurite outgrowth studies) or 100,000 cells/cm2 (for kinase activation analysis) on plates coated with poly-l-lysine (Sigma). After 24 h, cells were exposed to purified adenoviruses (multiplicity of infection [MOI] of 200) for 16 h and subsequently washed and placed in fresh culture medium. Transfection of PC6 cells was performed using Effectene (QIAGEN) as described previously (59).

Transfection of COS cells was performed using Superfect (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, COS cells were seeded into either six-well plates or 100-mm-diameter plates and 50 to 70% confluent monolayers were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), incubated with preformed DNA-Superfect complex (1 μg of plasmid DNA/3.5 to 5 μl of Superfect) in Opti-MEM I medium (GIBCO) for 4 h, washed, and placed in fresh culture medium.

GST pull-down analysis, immunoprecipitation, and immunoblotting.

To examine the association of Rit and Raf proteins, cell lysates were prepared from COS cells transiently transfected with 3 μg of empty pEBG (expressing unfused GST), pEBG-Rit-Q79L or pEBG-H-Ras-Q61L and either 2 μg of pcDNA3-HA-B-Raf-WT or pcDNA3-HA-C-Raf-WT-Flag. Cell monolayers were cultured for 36 h after transfection and harvested after an additional 5-h incubation in serum-free DMEM. The cells were harvested by scraping the cells in PBS and resuspending them in ice-cold kinase buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 50 mM KF, 50 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail [Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.]). Cells in the cell suspension were lysed by sonication on ice. The homogenate was centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min to eliminate the insoluble material, the protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad), and the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube. Detergent-soluble lysates (400 μg) were incubated with 22 μl of a 50% slurry of glutathione-Sepharose 4B (Amersham Biosciences) in a total volume of 1 ml for 1 to 2 h at 4°C with end-over-end rotation to allow isolation of the GST fusion proteins. The glutathione beads were then collected in a microcentrifuge (CR3i; Jovan, Winchester, Va.) for 5 min at 104 rpm at 4°C, and the supernatant was discarded. The pelleted glutathione beads were then washed twice with ice-cold kinase buffer, once with ice-cold 1 M NaCl kinase wash buffer (kinase buffer containing 1 M NaCl), and twice with ice-cold kinase buffer. The bound proteins were then released by boiling in Laemmli sample loading buffer for 5 min and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 10% polyacrylamide gels. To examine the interaction of Rit and endogenous Raf kinase isoforms, cell lysates (10 mg of total cell lysate per reaction mixture) were prepared from COS cells transiently transfected with pEBG, pEBG-Rit-Q79L, or pEBG-H-Ras-Q61L and subjected to GST pull-down analysis as described above.

To examine the interaction of Rit and Raf proteins by coimmunoprecipitation, cell lysates were prepared from COS cells transiently cotransfected with 3 μg of empty 3xFlag vector, 3xFlag-RitWT, 3xFlag-RitQ79L, or 3xFlag-H-RasQ61L together with 2 μg of Myc-B-Raf-WT or Myc-C-Raf-WT expression vector. Cell monolayers were allowed to recover for 36 h after transfection and serum starved for 5 h in serum-free DMEM in an incubator. The cells were then harvested by scraping the cells in PBS, resuspending them in ice-cold kinase buffer, and lysing them by sonication on ice. The homogenate was centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min (1.4 × 104 rpm in a refrigerated microcentrifuge) to eliminate the insoluble material, and the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube. Cleared cell lysates (400 μg) were incubated with either 2 μg of an anti-B-Raf or anti-C-Raf polyclonal antibody or 2 μg of anti-Myc monoclonal antibody as well as mouse or rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Santa Cruz) as a specificity control in a total volume of 1 ml for 2 h with gentle rotation at 4°C. Immunocomplexes were affinity absorbed onto 30 μl of protein G-Sepharose beads (Amersham) for an additional hour at 4°C with constant rotation. The Sepharose resin was collected by brief centrifugation (5 min at 104 rpm at 4°C) and washed extensively (as described above), and bound proteins were eluted by incubation for 5 min at 100°C in Laemmli buffer. Bound proteins and 10 μg of total cell lysate from each sample were resolved using SDS-10% polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Protran; Schleicher & Schuell Bioscience, Dassel, Germany) and subjected to immunoblotting using biotin-labeled anti-Flag or anti-Myc antibody, isoform-specific B-Raf and C-Raf antibody, or anti-phospho-specific Raf (Ser338) rat monoclonal antibody to detect phosphorylated Raf. Blots were stripped and reprobed with the appropriate antibody to ensure that equal amounts of recombinant proteins were expressed.

Immunoblots were blocked in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) and 1% casein (Sigma) for 1 h at 25°C and incubated with an appropriate dilution of the primary antibody in PBST containing 1% casein or 5% bovine serum albumin for 1 to 2 h. The immunoblots were washed three times with PBST before the addition of a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Zymed Laboratories, Inc., San Francisco, Calif.) or HRP-conjugated streptavidin (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) diluted 1:20,000 or 1:40,000 in PBST containing 1% casein, respectively. The signal was detected by chemiluminescence (SuperSignal West Pico system; Pierce) as described previously (59, 60). Immunoblots were stripped and reprobed to ensure equal expression of recombinant proteins as described previously (55, 59).

Raf kinase assays.

Raf kinase activation was determined by two methods. In vivo Raf kinase assays were also performed using a Raf kinase cascade assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology). Briefly, COS cells were transiently transfected using Superfect with 2 μg of pEBG-B-Raf-WT, pEBG-C-Raf-WT, or empty pEBG vector expressing unfused GST in the absence or presence of 6 μg of either 3xFlag-Rit-WT, 3xFlag-Rit-Q79L, 3xFlag-Rit-S35N, 3xFlag-H-Ras-Q61L, or empty 3xFlag vector. Cells were allowed to recover for 36 h and serum starved for 5 h by transfer to serum-free DMEM, and cell lysates were prepared in ice-cold kinase buffer. GST-B-Raf and GST-C-Raf were isolated by subjecting 1 mg of cell lysate to glutathione-Sepharose 4B resin pull down, and the resulting protein-bound glutathione resin was divided into two equal fractions. Half of the resin was subjected to a standard series of wash steps (see above), and the bound proteins were eluted by boiling in Laemmli buffer. Western blot analysis was performed using isoform-specific B-Raf and C-Raf antibodies to examine the levels of recombinant Raf protein in the kinase assays. Whole-cell lysates (12.5 μg) were subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti-GST (recombinant Raf protein), anti-Rit, or anti-Ras antibody to ensure that equal amounts of recombinant protein were expressed. The remaining portion of the GST pull-down buffer was washed twice with ice-cold kinase buffer and then three times with ice-cold assay dilution buffer (ADBI) (20 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid [MOPS] [pH 7.2], 25 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM dithiothreitol).

Coupled kinase reactions were initiated by adding the following mixture to the washed resin (final reaction volume of 38 μl): 10 μl of magnesium/ATP cocktail (75 mM MgCl2, 500 μM ATP in ADBI), 1.6 μl of purified MEK1 (0.4 μg), and 4 μl of purified ERK2 (1 μg). The resulting mixture was incubated with gentle shaking at 30°C for 30 min. An aliquot of the reactivated MEK1-ERK2 supernatant (4 μl) was then removed and added to a second-stage kinase reaction mixture containing 10 μl of ADBI, 10 μl of myelin basic protein (MBP) substrate (Upstate Biotechnology) (2 mg/ml, diluted in ADBI), and 10 μl of [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol) (ICN Inc.) (1 μCi/μl diluted in MgCl2/ATP cocktail) in a final volume of 34 μl. The second-stage reactions were performed in triplicate by incubation for 10 min at 30°C. Of the triplicate reaction mixtures, one reaction mixture was boiled in Laemmli buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide gels), and exposed to Kodak X-OMAT AR film for 30 min to 2 h at room temperature to visualize radiolabeled MBP. The amount of radiolabeled MBP in each reaction mixture was then quantified using a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager SF (model 455A). The remaining reaction mixtures (25 μl of each sample) were spotted onto P81 filter paper. The filter paper was washed three times for 5 min each time with 7.5% phosphoric acid, washed once with acetone for 5 min, and allowed to dry. The amount of 32P-labeled MBP was determined by scintillation counting. Background radioactivity in all cases was determined using lysates transfected with empty vector.

MAP kinase activation studies.

For transient-transfection assays, 70% confluent COS cell monolayers were transfected using Superfect reagent. To examine the effect of wild-type B-Raf overexpression on Rit signaling pathways, transfection reaction mixtures contained 1 μg of 3xFlag-Rit-Q79L, 3xFlag-H-Ras-Q61L, or an empty Flag vector and 1 μg of Myc-B-Raf-WT or empty Myc vector. To examine the requirement of B-Raf function on Rit-mediated ERK activation, cell monolayers were cotransfected with 2 μg of 3xFlag-Rit-Q79L, 3xFlag-H-Ras-Q61L, or p3xFlag and with 1 μg of either Myc-B-Raf-AA or an empty Myc vector. One day after transfection, cells were placed in serum-free DMEM for 5 h and then solubilized in 300 μl of ice-cold kinase lysis buffer. Approximately 50 μg of cell lysate was boiled in Laemmli buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blot analysis with anti-phospho-ERK or anti-phospho-MEK antiboduy Blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-ERK or anti-MEK antibody to ensure equal protein loading. Similar MAP kinase assays were performed in PC6 cells, with the exception that cells were transfected using Effectene (QIAGEN).

To determine the effects of kinase inhibitors on Rit-induced p38 MAPK and ERK1/2 activation, COS or PC6 cells were either left untreated or pretreated with Opti-MEM I medium supplemented with 10 μM SB203580 (Tocris, Ellisville, Mo.) or 10 μM PD98059 (Calbiochem) for 30 min and then transiently transfected with 2 μg of 3xFlag-Rit-Q79L, 3xFlag-H-Ras-Q61L, or empty Flag vector. Cells were incubated for an additional 4 h (COS cells) or 16 h (PC6 cells) in the presence of 10 μM inhibitor to allow for maximal gene expression. Thirty-six hours after transfection, cells were cultured in serum-free DMEM (with or without 10 μM SB203580 or PD98059) for 5 h and harvested in ice-cold kinase buffer, and 50 μg of total cell lysate was subjected to SDS-PAGE. The activation status of ERK1/2 or p38 MAPK was determined by immunoblot analysis using phospho-specific antibodies as described previously.

Neurite outgrowth studies.

To determine the effects of a variety of kinase inhibitors on Rit-induced neurite outgrowth, PC6 cells seeded at 104 cells/cm2 in poly-l-lysine-coated, 35-mm-diameter dishes were pretreated with either dimethyl sulfoxide, 10 μM PD98059, 10 μM GW5074, 25 μM SP600125 (Tocris), 10 μM LY294002, 10 μM PP2 or 10 μM PP3 (Calbiochem) for 30 min and then incubated overnight in the presence of Ad-GFP, Ad-Rit-Q79L/GFP, or Ad-Ras-Q61L plus Ad-GFP adenoviruses, each at an MOI of 200 (total virus MOI of 300 for the Ad-RasL61/Ad-GFP coinfection). As a positive control for neurite elongation, rat β-NGF (100 ng/ml) was added to a set of Ad-GFP-infected PC6 cell cultures at the time of infection. Infected cell cultures were incubated in fresh medium with or without inhibitors for an additional 24 h to allow neurite elongation to proceed, and the length of the neurites was determined in GFP-expressing cells by epifluorescence microscopy (59). GFP-expressing PC6 cells with neurites longer than one cell body in length were counted as positive. At least 200 cells were counted per experiment (in 9 to 12 random fields) with each experiment performed in triplicate. Images were examined under the appropriate illumination with an ×40 objective lens on an Axiovert 200 M microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) using OpenLab 3.1.4 imaging software (Improvision, Inc., Lexington, Mass.).

A second method for examining Rit-mediated neurite outgrowth involved transient transfection of PC6 cells with mammalian expression vectors. For these studies, PC6 cells were exposed to DNA-Effectene complexes for 9 to 16 h, replated after dilution (1:4 dilution), and treated with G418 drug (400 μg/ml) (GIBCO, San Diego, Calif.). Drug selection continued for 3 to 7 days, the cells were fixed with methanol-acetone (3:1), and the images were captured on an Axiovert 200 M phase-contrast microscope (Zeiss) with a 20 × lens objective using OpenLab 3.1.4 imaging software. We analyzed the percentage of neurite-bearing cells, neurite number per cell body, neurite length, and the number of branch points per neurite in two to four separate experiments as described previously (25).

To investigate the involvement of ERK and p38 MAP kinase signaling pathways on Rit-mediated neurite outgrowth, PC6 cells were pretreated with SB203580 (10 μM) or PD98059 (10 μM) for 30 min and transfected with 3xFlag-Rit-Q79L or 3xFlag-H-Ras-Q61L. To examine the requirement of isoform-specific Raf kinase function on Rit-induced neurite outgrowth, PC6 cells were transfected with 3xFlag-Rit-Q79L in the absence or presence of Myc-B-Raf-WT, Myc-B-Raf-AA, or Myc-C-RafKD, with empty Flag or Myc vector used as negative controls and 3xFlag-H-Ras-Q61L serving as a positive control for these studies.

Rit-GTP and Ras-GTP precipitation assays.

GST fusion proteins containing the Ras binding domain of C-Raf (residues 1 to 140) and the Rit binding domain of RGL3 (residues 610 to 709) were expressed and purified as described previously (55, 60). Rit and Ras activation was assessed essentially as described previously (60) with minor modifications. PC6 cells seeded in six-well plates were transfected with Flag-tagged wild-type Rit and Ras using Effectene and incubated for an additional 36 h to allow maximal gene expression. Cells were then starved in serum-free DMEM for an additional 12 h and stimulated for different times. Cell monolayers were washed once in ice-cold PBS and lysed in GST pull-down assay buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 250 mM NaCl, 50 mM KF, 50 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail) with sonication on ice. GST resin (10 μg of the appropriate fusion protein/20 μl of glutathione beads) was added to Rit (400 μg)- or Ras (200 μg)-expressing cell lysates in a total volume of 1 ml and incubated with rotation for 1 h at 4°C, and the resin was recovered in a 4°C microcentrifuge (5 min at 10,000 rpm). Rit-GTP assays were washed twice with GST pull-down buffer, once with GST pull-down buffer supplemented with 500 mM NaCl, and finally twice with ice-cold GST pull-down buffer before SDS-PAGE analysis. Ras-GTP assays were washed once with GST pull-down buffer, once with GST pull-down buffer plus 500 mM NaCl, once with GST pull-down buffer plus 1 M NaCl, once with GST pull-down buffer plus 500 mM NaCl, and finally twice with GST pull-down buffer. Bound GTP-Rit and GTP-H-Ras were detected by immunoblot analysis using anti-Flag monoclonal antibody.

RNA interference.

The mammalian expression vector pSUPER.gfp/neo (OligoEngine) was used for expression of siRNA in PC6 cells. The vector allows direct synthesis of siRNA transcripts using the polymerase-H1-RNA gene promoter and coexpresses GFP to allow detection of transfected cells. The gene-specific insert sequence ATGGCCAGTACTAACTCCT (target sequence [sense]), which was separated by a 9-nucleotide noncomplementary spacer (TCTCTTGAA ) from the reverse complement of the same Rit-specific 19-nucleotide sequence, was synthesized, subcloned into the BglII and HindIII sites of pSUPER.gfp/neo to generate pSUPER-Rit, and the insert was verified by DNA sequence analysis. Empty vector (pSUPER.gfp.neo) was used as a negative control in these studies. Expression constructs were introduced into PC6 cells by transfection using Effectene reagents, and the cells were subjected to G418 (200 μg/ml) selection. The expression of Rit, Ras, or Rin GTPase was analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Rit, anti-Ras, or anti-Rin monoclonal antibody as described above.

To determine the effects of siRNA-mediated knockdown of endogenous Rit on NGF signaling, PC6 cells seeded in six-well plates were transfected with either pSUPER-Rit or pSUPER.gfp.neo siRNA vector. Cell monolayers were subjected to G418 (400 μg/ml) selection for 2 days, serum starved for 5 h, stimulated with NGF (100 ng/ml) for 10, 15, or 60 min or left alone, and then harvested in kinase lysis buffer. The phosphorylation levels of p44/42 MAPK and p38 MAPK were detected by immunoblotting with phospho-specific antibodies.

To explore the requirement for Rit function in NGF-mediated neurite outgrowth, PC6 cells were transfected with the appropriate siRNA construct and then reseeded onto 35-mm-diameter dishes (1:4 dilution) in complete DMEM containing 400 μg of G418 per ml with or without NGF (100 ng/ml) stimulation to initiate differentiation. Pretreatment with PD98059 (10 μM) or SB203580 (10 μM) was used as control for these studies. The neurite outgrowth was analyzed, and the cells were photographed as described above 3 and 7 days after exposing the cells to NGF.

RESULTS

Rit activates p38 and ERK MAP kinase cascades in PC6 cells.

The biological functions of Ras-related GTP-binding proteins are dependent on their ability to activate diverse intracellular signaling pathways, many of which result in the stimulation of members of the MAP kinase superfamily of serine-threonine kinases (47). Since we have shown that activated Rit has a profound biological activity in PC6 cells (59) and there is a body of evidence that suggests that the ERK (2), JNK (32), p38 (36, 75), ERK5 (68), and PI3K/Akt kinase (30) pathways are involved in neuronal differentiation and survival signaling, we examined whether Rit activates additional MAP kinase family members in these cells. For these experiments, recombinant adenoviruses expressing GFP alone, coexpressing GFP and either wild-type or constitutively active Rit (RitL79), or expressing activated Ras (RasL61) alone were used to infect PC6 cells (25, 59, 60). As seen previously, a majority (>80%) of the PC6 cells infected with Ad-RitL79/GFP, Ad-RasL61, or control Ad-GFP adenovirus and then stimulated with NGF demonstrate robust neurite outgrowth, a prominent marker of PC6 cell differentiation (Fig. 1A) (2, 20, 59). In contrast, no change in morphology relative to that of uninfected PC6 cells was detected for cells infected with control GFP adenovirus alone or for cells stimulated with EGF (data not shown).

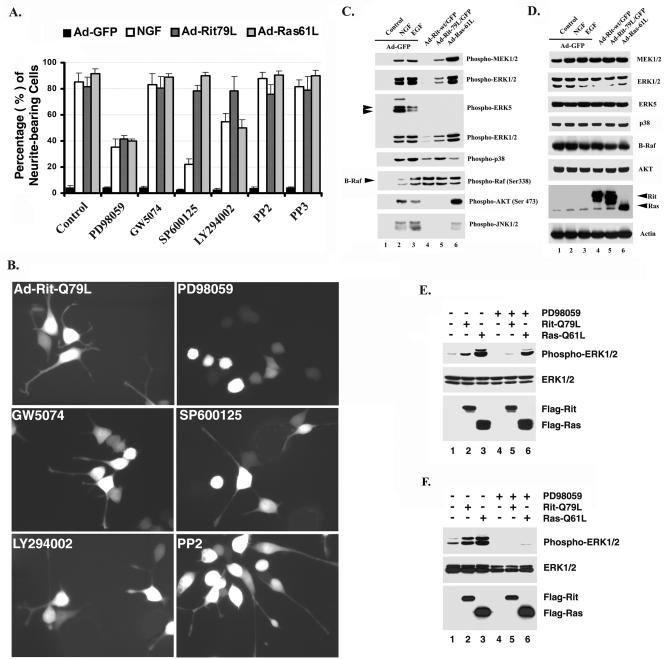

FIG. 1.

Activation of ERK and p38 MAP kinase pathways by constitutively active Rit. (A and B) Rit-induced neurite outgrowth is MEK1/2 dependent. PC6 cells were preincubated with dimethyl sulfoxide (control), PD98059 (10 μM), GW5074 (10 μM), SP600125 (25 μM), LY294002 (10 μM), PP2 (10 μM), or PP3 (10 μM) as indicated prior to infection with Ad-GFP or Ad-Rit-Q79L or coinfection with Ad-Ras-Q61L and Ad-GFP as described in Materials and Methods. Infected cells were identified by epifluorescence microscopy. Ad-GFP-infected PC6 cells stimulated with β-NGF (100 ng/ml) served as a positive control, while unstimulated cells provide a negative control for neurite outgrowth. Cells bearing neurites exceeding 1 cell body length were scored as a percentage of the total number of infected cells 36 h after infection. Values are means ± standard deviations (error bars) from four or five individual experiments. (C and D) RitL79 stimulates MEK1/2, ERK1/2, and p38 MAP kinase and B-Raf phosphorylation, but not ERK5, Akt, or JNK1/2. PC6 cells were cultured and infected with recombinant adenovirus expressing GFP alone (Ad-GFP) (lanes 1 to 3) or coexpressing GFP and wild-type Rit (Ad-Rit-wt) (lane 4), constitutively active Rit (Ad-Rit-79L) (lane 5), or activated H-Ras (Ad-Ras-61L) (lane 6) (MOI of 200) as described in Materials and Methods. After 36 h, cells were serum starved for 12 h and stimulated with NGF (100 ng/ml, 10 min) (lane 2) or EGF (100 ng/ml, 5 min) (lane 3) as indicated before preparation of whole-cell lysates. Cell lysates (50 μg) were resolved on SDS-10% polyacrylamide gels and subjected to immunoblot analysis. Blots were probed with anti-phospho-specific antibody against MEK1/2, ERK1/2, ERK5, p38, Raf (S338), Akt (S473), or JNK1/2 (pTpY183/185). Expression of recombinant Rit and Ras was evaluated by immunoblotting with anti-Rit and anti-Ras monoclonal antibodies, while equal protein loading was verified using an antiactin antibody. The endogenous levels of MEK1/2, ERK1/2, ERK5, p38 MAPK, B-Raf, and Akt were determined using protein-specific antibodies. (E and F) RitQ79L-mediated ERK activation is inhibited by PD98059. COS cells (E) or PC6 cells (F) were transfected with 2 μg of empty 3xFlag vector, 3xFlag-Rit-Q79L, or 3xFlag-H-Ras-Q61L after pretreatment with PD98059 (10 μM, lanes 4 to 6). Thirty-six hours after transfection, whole-cell lysates (50 μg) were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-phospho-ERK1/2 antibody. All data are representative of those obtained in at least three separate experiments.

In an initial attempt to define the potential roles of additional MAP kinase pathways in Rit-mediated neurite outgrowth, we examined whether Rit-induced PC6 cell differentiation resulted in the activation of protein kinases with demonstrated roles in PC12 neurite outgrowth or whether this process was attenuated by the addition of a series of specific kinase inhibitors. For these studies, PC6 cells were infected with either Ad-RasL61, Ad-RitL79/GFP, or control Ad-GFP adenoviruses and treated with pharmacological inhibitors that have been previously shown to be specific and were used at noncytotoxic concentrations (10, 39, 40, 59, 73), and the extent of neurite outgrowth was quantified 36 h postinfection. As shown in Fig. 1A and B, inhibiting either Src family kinases (PP2) (10 μM), JNK (SP600125) (25 μM), or the C-Raf inhibitor GW5074 (10 μM) had no effect on RasL61- or RitL79-mediated neurite outgrowth, although SP600125 strongly inhibited NGF-stimulated PC6 cell neuritogenesis. Interestingly, inhibiting PI3K (LY294002) (10 μM) inhibited NGF- and RasL61-induced neurite elongation, but as reported previously (59), inhibiting PI3K had no effect on RitL79-mediated morphological differentiation.

To extend this analysis, immunoblotting with antibodies that specifically recognize the phosphorylated forms of ERK, JNK, p38, ERK5, Raf, and Akt was used to examine the activation status of these kinases. As expected, RasL61 demonstrated potent stimulation of both the Raf-MEK-ERK kinase cascade and Akt kinase and modest activation of p38 and JNK MAP kinases but did not stimulate ERK5 (Fig. 1C and D). In contrast, infection with Ad-RitL79/GFP and Ad-Rit-WT/GFP resulted in potent stimulation of Raf phosphorylation, and cells expressing RitL79 developed a modest increase in the phosphorylation of MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 kinases but failed to activate JNK, ERK5, or Akt kinases. However, activated Rit potently stimulated the phosphorylation of p38. Even wild-type Rit induced levels of phospho-p38 that were slightly higher than those seen after infection with RasL61 adenovirus (Fig. 1C, lanes 4 and 6). Infection with GFP-expressing adenovirus did not result in stimulation of any kinase pathway, although as expected, both NGF and EGF stimulation of cells infected with GFP adenovirus resulted in potent activation of all the kinases that were examined (Fig. 1C, lanes 2 and 3).

Sustained activation of the MEK/ERK pathway has been suggested to play a crucial role in oncogenic Ras- and NGF-mediated differentiation of PC12 cells and in Rit-mediated neuritogenesis of PC6 cells (59). The importance of MEK/ERK signaling in Rit-differentiated PC6 cells was assessed using the specific MEK1 inhibitor PD98059. As expected, attenuating the ERK pathway with PD98059 (10 μM) markedly inhibited both NGF- and Ad-RasL61-mediated neurite outgrowth (Fig. 1A and B). Importantly, MEK inhibition also potently suppressed neurite outgrowth from PC6 cells after Ad-RitL79 infection (Fig. 1A and B). Immunoblotting with antibodies that specifically recognize the active phosphorylated form of ERK confirmed the inhibitory effect of PD98059 treatment on RitL79- and RasL61-mediated ERK activation in both COS and PC6 cells (Fig. 1E and F). Similar results were also found with a second MEK inhibitor, U0126 (data not shown). Thus, activation of the MEK/ERK pathway contributes to Rit-induced PC6 cell differentiation.

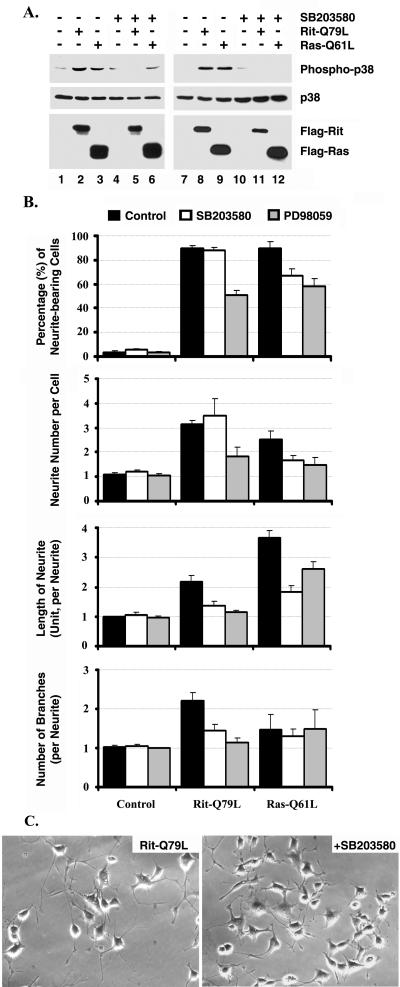

Rit activates p38 MAP kinases to promote neurite branching.

The importance of p38 MAP kinase signaling in Rit-induced neurite outgrowth of PC6 cells was assessed using the specific p38 inhibitor SB203580 (10 μM [12]). As shown in Fig. 2, exposure to SB203580 inhibited RitL79-mediated p38 activation in both COS and PC6 cells (Fig. 2A) but did not significantly decrease either the number of neurites per cell or the percentage of neurite-bearing PC6 cells (Fig. 2B and C). However, p38 MAP kinase inhibition potently decreased Rit-induced neurite length and the number of branch points per neurite from those of control cultures (e.g., in cells expressing RitL79, there were 2.21 ± 0.2 branch points per neurite and neurites were 2.17 ± 0.23 cell body lengths compared with 1.43 ± 0.16 branch points and 1.36 ± 0.17 cell body lengths for cells exposed to SB203580) (Fig. 2B and C). SB203580 treatment of Ad-RasL61-infected PC6 cells had a strikingly different effect, inhibiting both the percentage of neurite-bearing cells, number of neurites per cell, and total neurite length per cell (Fig. 2B). Therefore, constitutive activation of the p38 MAP kinase pathway is required for RasL61-induced neurite outgrowth in PC6 cells but has a more limited role in Rit-mediated PC6 cell neuronal differentiation, regulating neurite elongation and branching but not neurite initiation. These data indicate that the distinct morphology promoted by Rit in both PC6 and SHSY-5Y cells (25), evidenced by increased neurite elongation and arborization, is mediated in part through a signaling pathway that involves p38 MAP kinase.

FIG. 2.

Rit-induced neurite branching and elongation are SB203580 sensitive. (A) SB203580 inhibits Rit-mediated p38 activation. COS cells (lanes 1 to 6) or PC6 cells (lanes 7 to 12) were transfected with 2 μg of empty 3xFlag vector, 3xFlag-Rit-Q79L, or 3xFlag-H-Ras-Q61L after pretreatment with SB203580 (10 μM, lanes 4 to 6 and 10 to 12) for 30 min. Thirty-six hours after transfection, celllysates (50 μg) were prepared, resolved on SDS-10% polyacrylamide gels, and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-phospho-p38 MAPK antibody (top blots), anti-p38 antibody (middle blots), or anti-Flag antibodies (bottom blots). (B and C) Rit-induced neurite outgrowth is MEK and p38 dependent. The PC6 cells were transfected with 3xFlag vector (B), 3xFlag-Rit-Q79L (B and C), or 3xFlag-H-Ras-Q61L (B), subjected to G418 selection, in medium containing SB203580 (10 μM) (B and C) or PD98059 (10 μM) (B) as indicated. Random fields were photographed 72 h (C) after transfection, and cells bearing neurites of greater than 1 cell body length were counted. Values are means ± standard deviations (error bars) of three experiments.

Rit activates the Raf/MAP kinase cascade in a cell type-specific manner.

Since previous studies have failed to demonstrate elevated ERK activity in Rit-transformed NIH 3T3 cells (49, 51), next we investigated the mechanism by which Rit demonstrates cell-specific activation of ERK signaling in PC6 versus NIH 3T3 cells. The Raf kinases are major activators of the MEK/ERK cascade in Ras-induced signal transduction (6). Raf kinases interact with the core effector domain of Ras, and this region is highly conserved in Rit. However, tyrosine 32 and serine 39 in H-Ras were replaced by histidine and alanine, respectively, in the Rit effector domain (31, 56, 69). Of these residues, Ser39 has been found to provide important contacts stabilizing the Ras/Raf complex (38). Residues outside this domain are also involved, including arginine 41 in H-Ras which was replaced by a lysine residue in Rit (38). Therefore, it is unclear from sequence analysis whether the effector domain of Rit supports Raf protein association. Indeed, yeast two-hybrid analysis failed to demonstrate Rit interaction with any member of the Raf kinase family (55, 56).

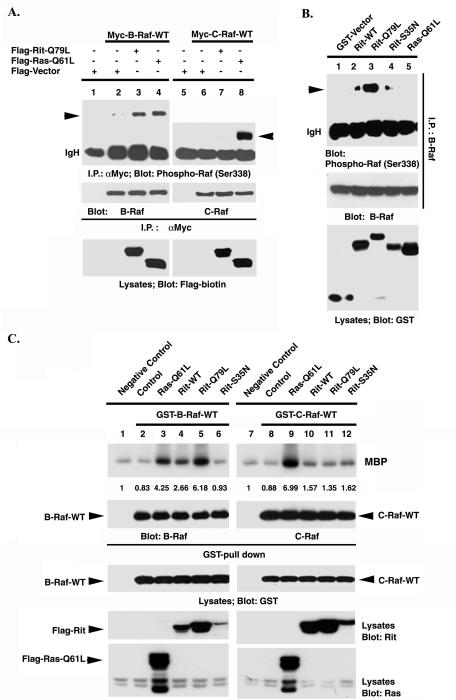

Given the presence of activated Raf kinase in Ad-RitL79/GFP-infected PC6 cell lysates (Fig. 1C, lane 5), we examined the ability of Rit to interact with Raf proteins using GST pull-down and coimmunoprecipitation analyses (Fig. 3). Because a vast literature has demonstrated that Raf kinases are genuine Ras effectors (6), the abilities of Rit and Ras to bind and activate Raf proteins were compared. For these studies, COS cells were transiently cotransfected with plasmids expressing unfused GST, GST-RitL79, or GST-RasL61 and either Flag-tagged wild-type C-Raf or HA-tagged wild-type B-Raf, and cell lysates were exposed to glutathione resin to isolate the GST fusion proteins. As shown in Fig. 3A, epitope-tagged C-Raf and B-Raf both coprecipitated with activated GST-Rit and GST-Ras proteins, but not with unfused GST (Fig. 3A, top blots, compare lanes 2 and 6 with lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8). To extend this analysis, COS cells were cotransfected with expression vectors for Flag-tagged wild-type Rit, activated Rit, or activated Ras, and Myc-epitope-tagged C-Raf or B-Raf and Raf kinase association was analyzed by anti-B-Raf or C-Raf immunoprecipitation. As seen in Fig. 3B, wild-type Rit, activated Rit, and activated Ras each coprecipitated from COS cell lysates in a Raf protein dependent-manner but were not precipitated using rabbit IgG in the reaction mixture or with anti-Myc antibody in the absence of coexpressed Raf protein (data not shown). Although RitL79 consistently bound both C-Raf and B-Raf, Rit demonstrated strong binding with B-Raf and only weakly associated with C-Raf in these studies (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 3 and 7). Wild-type Rit demonstrated slightly reduced binding compared to RitL79, suggesting that Raf association is dependent upon the GTP-bound state of Rit (Fig. 3B).

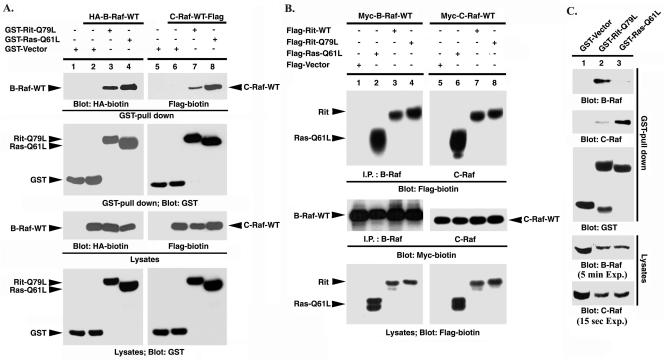

FIG. 3.

Rit binds both B-Raf and C-Raf. (A) Association of B-Raf and C-Raf with Rit. COS cells were transfected with empty GST vector, GST-Rit-Q79L, or GST-H-Ras-Q61L plus HA-B-Raf-WT (lanes 2 to 4), C-Raf-WT-Flag (lanes 6 to 8), or empty vector (lanes 1 and 5), and protein association was examined by GST pull-down analysis as described in Materials and Methods. The presence of Raf protein in the pull-down complex was detected by immunoblotting with biotinylated anti-HA or anti-Flag antibody. The efficiency of GST pull down and expression of transfected Rit or Ras proteins were examined by immunoblot analysis using anti-GST antibody, and expression of recombinant Raf was determined using biotinylated anti-HA or anti-Flag antibody. The results are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Association of B-Raf and C-Raf with Rit. COS cells were transfected with Myc-B-Raf-WT, Myc-C-Raf-WT, or empty Myc vector in the presence of 3xFlag-Rit-WT, 3xFlag-Rit-Q79L, 3xFlag-H-Ras-Q61L, or empty Flag vector as indicated, and protein association was examined by coimmunoprecipitation using anti-B-Raf or anti-C-Raf antibody as described in Materials and Methods. The precipitated Rit or Ras was detected by immunoblotting with biotinylated anti-Flag antibody, while the efficiency of coimmunoprecipitation and the expression of recombinant proteins were determined using biotinylated anti-Myc or anti-Flag antibody. The results are representative of three individual experiments. I.P., immunoprecipitation. (C) Rit interacts with endogenous B-Raf. COS cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding GST-Rit-Q79L, GST-H-Ras-Q61L, or GST alone, whole-cell lysates were prepared, and aliquots of each cell lysate (10 mg) were subjected to GST pull-down analysis as described in Materials and Methods. The Raf proteins precipitated by glutathione-agarose-bound GST-Rit or GST-Ras were identified by immunoblot analysis with anti-B-Raf or anti-C-Raf antibody. Exp., exposure.

To confirm these interactions and to further examine the relative affinity of Rit binding to the Raf kinases, we expressed GST-RitL79 and GST-RasL61 proteins in COS cells, precipitated the GST fusion proteins from whole-cell lysates, and assayed for coprecipitation of endogenous Raf proteins by immunoblotting with isoform-specific anti-Raf antibodies (Fig. 3C). Both C-Raf and B-Raf were found to associate in a GST-Ras61L complex, although GST-RasL61 consistently bound more C-Raf than B-Raf (Fig. 3C, compare lanes 3 of the top two blots). In contrast, GST-RitL79 was found to robustly associate with B-Raf but only weakly bound endogenous C-Raf (Fig. 3C, compare lanes 2 of the top two blots), although C-Raf is the predominant Raf isoform expressed in these cells (see Fig. 5A). Thus, although Rit is capable of interacting with both C-Raf and B-Raf, it preferentially associates with B-Raf even in the presence of a large excess of endogenous C-Raf.

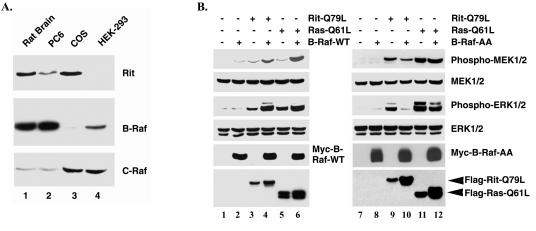

FIG. 5.

Rit promotes ERK activation in a B-Raf-dependent manner. (A) Rit and Raf protein distribution. Whole-cell lysates (100 μg) prepared from adult rat brain or from PC6, COS, or HEK293 cells were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the expression of endogenous Rit, B-Raf, and C-Raf proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with specific antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Rit activates MEK/ERK signaling in a B-Raf-dependent manner. COS cells were transfected with 3xFlag-Rit-Q79L, 3xFlag-H-Ras-Q61L, or empty Flag vector in the presence of Myc-B-Raf-WT, Myc-B-Raf-AA, or empty Myc vector as indicated. Cell lysates (50 μg) were resolved on SDS-10% polyacrylamide gels and subjected to immunoblot analysis using either anti-phospho-MEK or anti-phospho-ERK antibody. The levels of endogenous ERK/MEK expressed and transfected proteins were examined by immunoblotting with the appropriate antibodies as indicated. The results shown are from one experiment that was representative of the three independent experiments performed.

Rit activates B-Raf.

The experimental results shown in Fig. 3 suggest that Rit interacts directly with B-Raf to induce its activation. To prove that Rit could serve as a signaling intermediate to regulate B-Raf activation, we examined the nucleotide dependence of Rit association and activation of B-Raf. Confirmation of the ability of Rit to activate B-Raf was obtained in COS cells transiently transfected with expression vectors for the Raf proteins and wild-type, dominant-negative (predominantly GDP-bound, RitN35), or constitutively active Rit (predominantly GTP-bound, RitL79), or an empty control vector (Fig. 4A and B). Activated H-Ras, which has been shown to activate both Raf isoforms, was used as a control for these studies. Lysates normalized for levels of exogenously expressed Raf protein were immunoprecipitated and assayed by using either a phospho-specific Raf antibody (Fig. 4A and B) or an in vitro kinase assay (Fig. 4C). As illustrated in Fig. 4A and C, whereas RasL61 resulted in robust ∼7-fold activation of C-Raf, activated Rit only modestly activated C-Raf (1.35-fold) and failed to exhibit stimulation above that for either wild-type or dominant-negative Rit under similar experimental conditions. In contrast, activated Rit and Ras both elicited potent B-Raf activation, although RitL79 resulted in more robust stimulation (6.2- versus 4.2-fold, respectively) (Fig. 4B and C). Importantly, even wild-type Rit induced a nearly threefold activation (2.7-fold) of B-Raf, perhaps explaining its ability to induce neurite outgrowth when expressed in PC6 cells (59). As expected, the predominantly GDP-bound dominant-negative Rit mutant (RitN35) failed to stimulate B-Raf activation, as monitored by phospho-specific Raf immunoblotting and in vitro kinase assay (Fig. 4B and C). Taken together, these results reveal a potential novel signaling pathway involved in Rit-induced neuronal differentiation through B-Raf and ERK.

FIG. 4.

Activation of B-Raf by Rit. (A) Rit stimulates B-Raf phosphorylation in COS cells. COS cells seeded in 100-mm-diameter dishes were transfected with 6 μg of 3xFlag vector, 3xFlag-Rit-Q79L, or 3xFlag-H-Ras61L in the absence (lanes 1 and 5) or presence of 2 μg of Myc-B-Raf-WT (lanes 2 to 4) or Myc-C-Raf-WT (lanes 6 to 8), whole-cell lysates were prepared, and Raf proteins were immunoprecipitated (I.P.) using anti-Myc (αMyc) monoclonal antibody as described in Materials and Methods. The resultant immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-phospho-Raf (S338) antibody (top blots) to determine the activation status of the Raf proteins, anti-B-Raf or C-Raf antibody (middle blots) to determine the levels of Raf protein in the precipitates, and biotinylated anti-Flag antibody (bottom blots) to determine the expression of transfected Rit and Ras protein. Similar results were seen in several independent experiments. (B) Rit-induced B-Raf activation is GTP dependent. PC6 cells were transfected with 1.5 μg of empty GST vector (lane 1), GST-Rit-WT (lane 2), GST-HA-Rit-Q79L (lane 3), GST-Rit-S35N (lane 4), or H-Ras-Q61L (lane 5) in the presence of 0.5 μg of HA-B-Raf-WT. B-Raf was immunoprecipitated (I.P.) using anti-B-Raf antibody as described in Materials and Methods, and the amount of active B-Raf was examined by immunoblotting with anti-phospho-Raf (S338) antibody. (C) Rit induces B-Raf kinase activity in COS cells. COS cells were transfected with GST-B-Raf-WT, GST-C-Raf-WT, or empty GST vector in the absence or presence of 3xFlag-Rit-WT, 3xFlag-Rit-Q79L, 3xFlag-Rit-S35N, or 3xFlag-H-Ras-Q61L as indicated. Raf kinase activity was determined in GST pull-down fractions by the incorporation of 32Pi into MBP as described in Materials and Methods. The data are representative of two or three experiments with similar results. Immunoblot analysis using both anti-GST and anti-Raf antibodies was used to demonstrate equal loading of GST-Raf protein in the kinase assays, while anti-Rit and anti-Ras antibodies were used to examine recombinant Rit and Ras expression as shown.

Rit-mediated neurite outgrowth is B-Raf dependent.

The studies in Fig. 4 suggest that the inability of Rit to activate ERK/MAPK in NIH 3T3 cells can be explained by its inability to stimulate C-Raf. In addition, these data suggest that an essential protein is absent in NIH 3T3 cells that is normally present in PC6 cells. An obvious candidate for such a protein would be B-Raf, whose expression is highly restricted to the nervous system (62). In fact, NIH 3T3 cells predominantly express C-Raf, but not B-Raf, while PC6 cells express both Raf isoforms (Fig. 5A) (67). To determine whether limiting B-Raf levels might affect the ability of Rit to activate ERK, we examined Rit signaling in COS cells overexpressing wild-type B-Raf. Immunoblotting with isoform-specific Raf antibodies demonstrates that COS cells normally express high levels of endogenous C-Raf and Rit but only very low levels of B-Raf (Fig. 5A). The activation state of the Raf-MEK-ERK kinase cascade was monitored by phospho-specific antibodies that recognize the activated forms of MEK and ERK. As shown in Fig. 5B (left blots, compare lanes 1, 4, and 6), COS cells coexpressing wild-type B-Raf and RitL79 displayed robust MEK-ERK MAP kinase activity, a level only slightly lower than that elicited by coexpressing constitutively active H-Ras and B-Raf. In contrast, the expression of wild-type B-Raf, RasL61, or RitL79 resulted in modest ERK activation (Fig. 5B, lanes 2, 3, and 5).

A second condition of this hypothesis is the notion that Rit signaling should be sensitive to alterations in B-Raf function. To examine this issue, we made use of a B-Raf mutant (B-RafAA) in which the major sites for oncogenic Ras-induced phosphorylation (threonine 598 and serine 601) that are essential for Ras-mediated B-Raf activation are replaced by alanine (78). These substitutions abolish Ras-induced B-Raf activation without altering the association of B-Raf with other signaling molecules. As shown in Fig. 5B (right blots), the expression of mutant B-RafAA potently inhibited RitL79-induced ERK kinase activation (compare lanes 9 and 10) but only modestly reduced RasL61-mediated ERK kinase stimulation (compare lanes 11 and 12). Consistent with these results was the finding that treatment with a C-Raf-specific inhibitor (GW5074) had no effect on Ad-RitL79-induced PC6 cell differentiation (Fig. 1A and B).

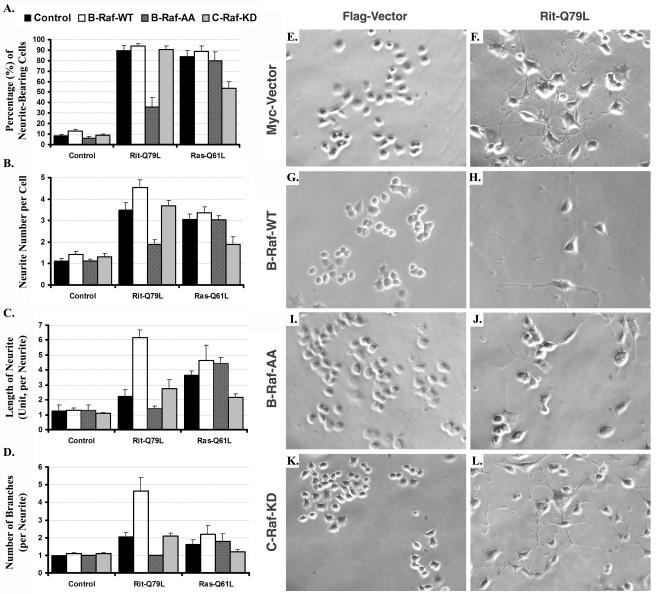

The experiments of Fig. 5 suggest that Rit-mediated signaling is greatly affected by the presence of B-Raf. Since B-Raf is the major neuronal Raf isoform and is highly expressed in the central nervous system and PC6 cells (Fig. 5A), next we examined the role of the Raf kinase isoforms in Rit-mediated PC6 cell differentiation. For this comparison, PC6 cells were transiently transfected with plasmids expressing RitL79, RasL61, or a control vector and either wild-type B-Raf, B-RafAA, or a kinase-inactive C-Raf mutant (C-RafKD) (78), and neurite outgrowth was assessed 3 days (results were similar; data not shown) or 1 week after transfection.

As shown in Fig. 6, RasL61 expression resulted in robust neurite elongation, which was only modestly altered by coexpression of wild-type B-Raf or B-RafAA. In contrast, expression of C-RafKD markedly inhibited all aspects of RasL61-induced neurite outgrowth, reducing the percentage of neurite-bearing cells (Fig. 6A), number of neurites per cell (Fig. 6B), total neurite length per cell (Fig. 6C), and number of branch points per neurite (Fig. 6D). As expected, RitL79 expression resulted in robust PC6 cell differentiation (25, 59), and in agreement with our model, coexpression of C-RafKD failed to inhibit Rit-mediated morphological differentiation (Fig. 6L). Although dominant-negative C-Raf had no effect on neurite outgrowth, expression of B-RafAA potently inhibited RitL79-mediated differentiation (Fig. 6). This result is in accordance with the previous finding that B-Raf activity plays an essential role in Rit-mediated ERK kinase activation (Fig. 5) and the importance of ERK kinase signaling in Rit-dependent neuronal differentiation (25, 59). Surprisingly, although PC6 cells express high levels of endogenous B-Raf (Fig. 5A), coexpression of exogenous B-Raf had a potent stimulatory effect on Rit-mediated neuronal differentiation (Fig. 6H). Compared with cells expressing RitL79 alone, cells coexpressing activated Rit and B-Raf possessed more neurites per cell body (Fig. 6B and J), exhibited dramatic increases in total neurite length per cell (Fig. 6C), and developed more than twice the number of branch points per neurite (Fig. 6D). Taken together, these results demonstrate that activation of a B-Raf/ERK kinase pathway is required for Rit-induced neurite outgrowth.

FIG. 6.

Rit induces neurite outgrowth in a B-Raf-dependent manner in PC6 cells. PC6 cells were transfected with 3xFlag-Rit-Q79L, 3xFlag-H-Ras-Q61L, or empty Flag vector plus Myc-B-Raf-WT, Myc-B-Raf-AA, Myc-C-RafKD, or empty Myc vector and then subjected to G418 selection. The percentage of neurite-bearing cells (A), number of neurites per cell (B), neurite length (C), and number of branch points per neurite (D) were analyzed 7 days after reseeding as described in Materials and Methods. Values are means ± standard deviations (error bars) from two separate experiments performed in triplicate. Random fields were photographed (using OpenLab 3.1.4 imaging software) by phase-contrast microscopy (E to L).

Growth factors activate Rit.

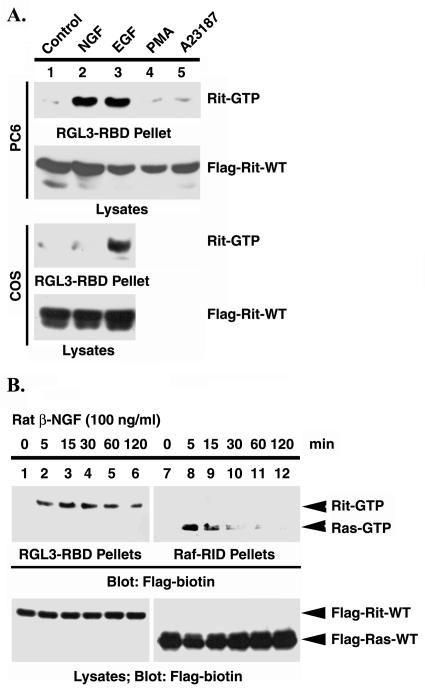

Because of the potent biological actions of Rit in PC6 cells, we wished to investigate the signaling pathways that result in Rit activation. Due to the lack of an effective Rit antibody for use in conventional radiolabeled GTP-loading experiments (18, 52), we developed an affinity pull-down assay system, which has been widely applied to the analysis of Ras-like GTPases (60). Previous studies have demonstrated a GTP-dependent interaction between Rit and RID of RGL3, a novel RalGEF first identified in a yeast two-hybrid screen for Rit effector proteins (55). Thus, we utilized this interaction to determine the in vivo levels of GTP-bound Rit. For this purpose, the RGL3-RID was fused to GST (GST-RGL3-RID) and purified from bacteria for use as a pull-down probe. The specificity of this probe was confirmed in studies demonstrating the ability of GST-RGL3-RID to affinity precipitate GTP-bound, but not GDP-bound, wild-type Rit (55).

Previous studies have demonstrated the importance of members of the Ras gene family in controlling cell growth and differentiation in response to trophic factors in PC12 cells, including NGF-mediated activation of the closely related Rin GTPase (60). As an initial step in characterizing the regulation of Rit in vivo, the involvement of polypeptide growth factors and the second messengers, diacylglycerol and calcium, on the activation of Rit transiently expressed in PC6 cells was examined. PC6 cells transiently transfected with Flag-tagged Rit were incubated in growth factor-deficient medium for 12 h prior to treatment with NGF, EGF, the diacylglycerol analogue PMA (100 ng/ml), or the calcium ionophore A23187 (5 μM). Cell lysates were prepared after stimulation, and GTP-bound Rit was retrieved using GST-RGL3-RBD precoupled to glutathione resin. Subsequently, Rit-GTP levels were analyzed by immunoblot analysis.

Figure 7A shows that whereas serum-starved PC6 cells had low levels of Rit-GTP, NGF and EGF stimulation rapid increased the amount of Flag-Rit-GTP collected by GST-RGL3-RID, while no response was observed for both PMA and A23187 under the same experimental conditions. The time course of NGF-mediated Rit activation was also examined (Fig. 7B). Activation of Rit reached a maximal level between 5 and 15 min after NGF stimulation and remained elevated for at least 2 h. The alterations in the level of Rit-GTP were not a consequence of changes in Flag-Rit expression in response to growth factor stimulation, because Rit protein remained constant (Fig. 7B). A similar time course was seen with EGF-mediated Rit activation (data not shown). Rit activation was correlated with the onset of NGF-induced Ras activation, a known downstream effect of NGF-mediated signaling (53, 60). However, time course analysis revealed that both the activation kinetics and duration of the GTP-bound state for these two G proteins differed, with H-Ras activation occurring more rapidly and being far more transient than that for Rit (Fig. 7B, compare the top blots). Taken together, these results demonstrate that stimulation of both NGF and EGF receptor signaling pathways in PC6 cells results in the rapid and prolonged activation of Rit.

FIG. 7.

Growth factor-induced Rit activation. (A) PC6 cells and COS cells were transiently transfected with expression constructs for 3xFlag-Rit-WT. Prior to preparation of whole-cell lysates, cells were serum starved for 12 h and then stimulated with either NGF (100 ng/ml, 10 min), EGF (100 ng/ml, 5 min), PMA (100 ng/ml, 1 h), or A23187 (5 μM, 1 h). Rit-GTP was recovered with GST-RGL3-RBD. Each reaction mixture contained (in a final volume of 1 ml) 200 μg of clarified cell lysate, 10 μg of GST-RGL3-RBD, and glutathione-agarose resin. After incubation for 1 h at 4°C, the samples were pelleted and washed as described in Materials and Methods. The Rit-GTP precipitated by GST-RGL3 was detected by immunoblot analysis with biotinylated anti-Flag monoclonal antibody. The expression level of recombinant GTPase present in the lysate was also determined by immunoblot analysis. (B) NGF induces prolonged Rit activation in PC6 cells. PC6 cells were transiently transfected with 3xFlag-Rit-WT or 3xFlag-Ras-WT, stimulated with NGF (100 ng/ml) for the indicated periods of time, and Rit-GTP and H-Ras-GTP levels were determined using GST-RGL3 or GST-Raf-RBD (for H-Ras) as described in Materials and Methods. The data are from one experiment that was representative of the three experiments performed.

Previous studies have shown that the closely related Rin GTPase is regulated by growth factor signaling in neuronal cell lines, but not in nonneuronal cell types, suggesting a requirement for neuronal-cell-specific regulatory factors (60). To examine whether Rit might share tissue-restricted regulatory factors with Rin, the ability of EGF to induce Rit activation in COS cells was analyzed. Consistent with its wide tissue expression profile, EGF stimulation resulted in Rit activation in COS cells (Fig. 7A, two bottom blots). Thus, Rit can be activated by receptor tyrosine kinase signaling pathways in a variety of cell lines.

Involvement of Rit in NGF-induced MAP kinase activation and neurite formation.

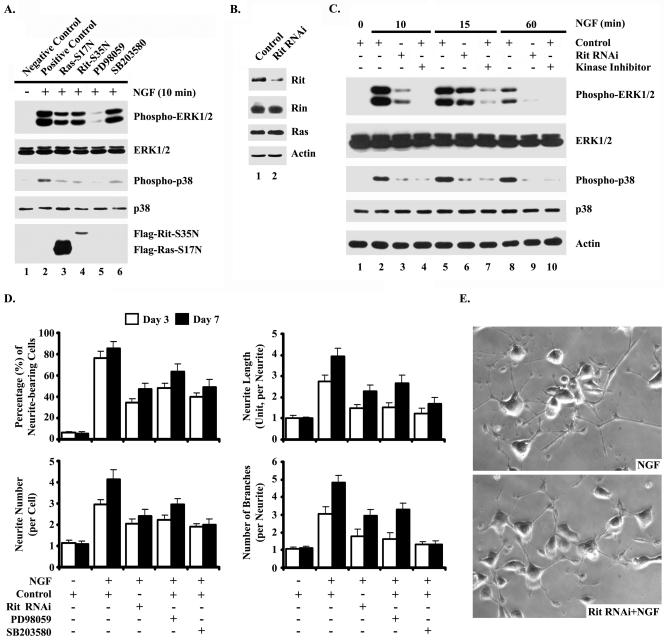

Since both NGF and Rit stimulate neurite outgrowth and NGF can activate Rit, it is possible that Rit may be a critical downstream signaling molecule for neuronal differentiation (59). To begin to test this possibility, we examined the ability of a dominant-negative mutant of Rit (Rit-S35N) to disrupt NGF-mediated activation of MAP kinase signaling pathways in PC6 cells. For this analysis, PC6 cells were transiently transfected with vectors expressing Flag-RitN35, Flag-RasN17 (dominant-negative H-Ras mutant), or control plasmid and maintained in G418-containing growth medium to isolate transfected cells. Exposing cultures transfected with empty vector to NGF for 10 min resulted in potent activation of both ERK and p38 MAP kinase cascades, as expected (Fig. 8A). Expression of either RitN35 or RasN17 (Fig. 8A) resulted in the potent inhibition of the NGF-mediated activation of both ERK and p38 MAP kinases. Interestingly, expression of both dominant-negative mutant GTPases result in approximately equal inhibition of the MAP kinase cascade, although Flag-RitN35 is expressed at significantly lower levels than RasN17 (Fig. 8A, compare lanes 3 and 4 in the bottom blot). These data suggest that Rit function is required for NGF-mediated MAP kinase activation in PC6 cells.

FIG. 8.

Rit is an essential component of NGF-mediated neurite outgrowth and MAP kinase signaling pathways. (A) Dominant-negative Rit attenuates NGF-mediated signaling. PC6 cells were transfected with 3xFlag-Rit-S35N, 3xFlag-H-Ras-S17N, or empty 3xFlag vector and then subjected to G418 selection. Prior to preparation of whole-cell lysates, cells were serum starved for 12 h in the presence of kinase inhibitor (PD98059 or SB203580) as indicated and stimulated with NGF (100 ng/ml) for 10 min, and the phosphorylation status of ERK1/2 and p38 MAP kinases was analyzed by immunoblotting with phospho-specific antibodies. The expression levels of recombinant Rit or Ras protein and endogenous ERK1/2 and p38 MAP kinases were examined by Western blotting. The results are from one experiment that was representative of the four experiments performed. (B) siRNA-mediated inhibition of Rit. PC6 cells were transiently transfected with either empty vector (control) or with an si-Rit RNA construct designed to selectively target endogenous Rit. Whole-cell lysates were prepared 40 h posttransfection, and equivalent amounts of total protein were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for the indicated proteins. Actin was used as a loading control. RNAi, RNA interference. (C) Rit is required for NGF-dependent MAP kinase signaling. PC6 cells were transfected with si-Rit (lanes 3, 6, and 9) or empty vector (lanes 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, and 10) and subjected to G418 selection. Pretreatment of control cells with either MEK/ERK (10 μM PD98059; phospho-ERK panel) or p38 (10 μM, SB203580 phospho-p38 panel) kinase inhibitors was used as control (lanes 4, 7, and 10). Cells were serum starved and then stimulated with NGF (100 ng/ml) for the indicated periods of time. The activation status of ERK1/2 and p38 MAP kinases was analyzed by immunoblotting with the appropriate phospho-specific antibodies. The expression levels of ERK1/2 and p38 MAP kinases were determined with protein-specific antibodies. Actin was used as a loading control. (D and E) Rit is required for NGF-mediated neurite extension. PC6 cells were transfected with si-Rit or empty vector, stimulated with NGF (100 ng/ml), and selected with G418 as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were pretreated with PD98059 (10 μM) or SB203580 (10 μM) as controls. The percentage of neurite-bearing cells, number of neurites, length of neurites, and number of branch points at days 3 and 7 were determined (panel D). Random fields were photographed at days 3 and 7 (day 7 micrographs are shown in panel E). At least 300 cells were assessed in each experiment, and values are means ± standard deviations (error bars) from two experiments.

To assess directly the contribution of Rit GTPase to NGF-dependent PC6 cell differentiation, we selectively inhibited the expression of Rit in PC6 cells using siRNA-mediated RNA interference (14). First, we prepared and examined the ability of an si-Rit RNA construct to down-regulate the expression of endogenous rat Rit. Transiently transfected PC6 cells (50 to 60% transfection efficiency) were analyzed for Rit expression by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 8B, expression of the si-Rit construct significantly reduced endogenous Rit expression but not that of the closely related Rin or H-Ras GTPases. Inhibiting Rit expression had no noticeable effect on cell proliferation or morphology under standard in vitro growth conditions (data not shown).

Since the expression of dominant-negative Rit appears to interfere with NGF-dependent MAP kinase pathway activation (Fig. 8A), we next assessed the effect of Rit knockdown on MAP kinase signaling pathways in PC6 cells. Cells were transiently transfected with the si-Rit construct or with empty vector, the population of transfected cells was enriched by antibiotic selection for 48 h, and the surviving cells were serum starved for 5 h prior to treatment with NGF. As expected, NGF stimulation of serum-starved PC6 cells expressing the control vector demonstrated a robust and rapid stimulation of both the ERK and p38 MAP kinases. As reported previously (36), the duration of NGF-mediated activation for these two MAP kinase cascades differed, with ERK activation being more transient than that for p38 (Fig. 8C). In contrast, siRNA-mediated inhibition of Rit expression resulted in a significant disruption in NGF-dependent MAP kinase signaling, causing an almost complete blockade in p38 stimulation and inhibiting both the duration and amplitude of ERK activation. The alterations in MAP kinase activation were not a consequence of changes in protein expression, because both ERK and p38 protein levels remained constant (Fig. 8C). These results define Rit as a novel component of the regulatory machinery in PC6 cells contributing to the integration of MAP kinase signaling in response to NGF stimulation.

We used the same strategy to examine the requirement for Rit in NGF-mediated neuronal differentiation. As shown in Fig. 8D and E, exposing cultures transfected with empty vector to NGF for 3 or 7 days resulted in the appearance of neurite outgrowth in approximately 80% of G418-resistant cells, whereas uninduced cultures expressing either si-Rit or empty vector continued to divide and showed no evidence of neurite formation in the absence of NGF (Fig. 8D). However, expression of si-Rit resulted in potent inhibition of all aspects of NGF-mediated neurite outgrowth, including a reduction in the percentage of neurite-bearing cells, neurite length, number of neurites per cell body, and neurite branching (Fig. 8D and E). Indeed, the effects arising from the loss of endogenous Rit on NGF-mediated PC6 cell differentiation rivaled those resulting from chronic exposure to MEK or p38 inhibitors (Fig. 8D). Taken together, these data suggest that Rit plays a crucial role in coupling NGF stimulation to the activation of both ERK and p38 MAP kinase signaling pathways in PC6 cells and function in NGF-dependent neuronal differentiation.

DISCUSSION

The continued discovery of novel Ras-related small GTPases has stimulated studies designed to investigate whether these newly identified G proteins serve redundant physiological roles or possess distinct cellular functions (45, 64). Previous studies have demonstrated the importance of members of the Ras gene family in controlling cell growth and differentiation in response to trophic factors in PC12 cells, including NGF-mediated activation of the closely related Rin GTPase (60). Sequence comparisons suggest that the Rit, Rin, and Drosophila Ric small GTPases represent the original members of a novel branch of Ras-related GTPases (56, 69), whose conservation from flies to humans suggests preservation of important physiological functions. We have previously shown that Rit can signal to Ras-responsive elements and transform NIH 3T3 cells to tumorigenicity without activating the ERK, JNK, p38, or PI3K/Akt kinases, indicating that Rit regulates growth control by different effector pathways than other transforming members of the Ras subfamily (25, 49, 59). In addition, we have demonstrated that expression of activated Rit is capable of inducing potent neurite outgrowth in both PC6 and SHSY-5Y neuronal cell lines in a MEK/ERK-dependent, PI3K/Akt-independent manner (25, 59). These studies suggest that Rit likely serves as a critical signal transducer of signals regulating both cellular growth and differentiation. Indeed, in this report, we demonstrate that Rit activation is a direct downstream effect of growth factor receptor activation, including NGF, and that selective inhibition of Rit expression can attenuate NGF-induced differentiation events and MAP kinase signaling. In addition, we used expression of constitutively active Rit in PC6 cells to explore the signaling pathways required for neurite outgrowth.

The important and novel findings of these studies include the following. (i) Rit plays a crucial role in coupling NGF stimulation to MAP kinase signaling pathways and PC6 cell neuritogenesis. (ii) Rit activates ERK and p38 MAP kinases, but not JNK, ERK5, or PI3K/Akt kinase signaling pathways in PC6 cells. (iii) Rit demonstrates isoform-specific Raf kinase binding and activation, associating with and activating the neuronal B-Raf isoform, but not C-Raf, explaining its cell type-specific activation of the ERK MAP kinase cascade. (iv) Inhibition of MEK inhibits Rit-induced neurite initiation. (v) Inhibition of p38 MAP kinase activity inhibits Rit-induced neurite elongation and branching, but not initiation. Together, these data indicate that two distinct signaling mechanisms mediate Rit-induced neurite outgrowth in pheochromocytoma cells: (i) a MEK-dependent signaling mechanism that supports neurite initiation and (ii) a p38-dependent signaling pathway that supports neurite arborization.

Considerable knowledge has been generated in the identification of trophic factors that support differentiation of neurons and neural tumor cells. Many growth factors, cytokines, and hormones have been found to regulate axonal and dendritic growth (24), although neurotrophins appear to have especially prominent and widespread effects (8, 23). For example, axonal outgrowth in sympathetic cervical neurons, such as those derived from PC12 cells and superior cervical ganglia, is increased upon NGF exposure (1, 35, 57). In addition, increases in intracellular cyclic AMP (58, 66) and calcium ion levels (48) have been shown to regulate neuron morphology. Recent studies indicate that Rit signaling promotes differentiation and cell survival in PC6 cells (25, 59).

To determine whether Rit is involved in transducing neuronal differentiation and survival signaling, we investigated in vivo Rit regulation. When PC6 cells are stimulated with NGF or EGF, Rit is rapidly activated (Fig. 7A). These studies provide the first demonstration of ligand-induced Rit activation and establish Rit as a direct downstream target of growth factor-induced receptor tyrosine kinase signaling pathways in both PC6 and COS cells. In addition, Rit does not appear to be regulated by second messenger signaling pathways known to regulate neuronal differentiation, since both agents that increase intracellular calcium levels and treatment with PMA, which mimics diacylglycerol, failed to stimulate cellular Rit-GTP levels in PC6 cells (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, although NGF- and EGF-induced activation of Rit and Ras is rapid, Rit remains activated for an extended period, whereas the activation of Ras is more transient (Fig. 7B). Because the activation cycle of Ras GTPases is regulated by their interaction with specific guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) (3, 44), these results suggest that Rit and Ras are probably regulated by distinct regulatory proteins. To date, no Ras-GEF has been demonstrated to stimulate guanine nucleotide exchange on Rit either in vivo or in vitro. However, there are a variety of Ras-family GEFs expressed in the central nervous system which might serve as Rit regulators (44). Given the fact that many of these GEFs have demonstrated activity towards H-Ras, it will be important to determine whether they also regulate Rit, and if so, it is likely that the differential regulation of Ras and Rit activation will be quite complex. Identification of the GEFs and GAPs that regulate Rit function and determining whether additional extracellular stimuli control cellular Rit-GTP levels will be topics of future investigation.

Studies reported here also provide evidence implicating Rit function in NGF-mediated neuronal differentiation. Rit is temporally and spatially expressed in many tissues, including the developing brain (31, 59), which suggests a function for Rit during neuronal development (25, 59). We have shown that the ability of NGF to induce neuronal differentiation in PC6 cells can be blocked by expression of a dominant-negative RitN35 mutant (59), and more importantly, by selective inhibition of endogenous Rit expression (Fig. 8). Thus, Rit function plays a critical role in the process of neurite outgrowth in PC6 cells. The molecular mechanisms governing the cytoskeletal changes necessary for neurite outgrowth are only beginning to be understood, although members of the Ras and Rho small GTPase subfamilies are involved in mediating neuronal development and regeneration (24). NGF is known to induce neurite outgrowth through the activation of Ras, and a study in NIE115 neuroblastoma cells indicates that Rac and Cdc42 act downstream of Ras during neurite outgrowth (9, 13). Whether Rit modulates the activity of Rac1 or Cdc42 or the activity of another protein involved in neurite outgrowth remains to be addressed. To more firmly define a role for Rit in NGF-mediated differentiation signaling, it is therefore necessary to undertake a detailed analysis of Rit function in primary neurons and to characterize cells derived from mice with absolutely no Rit expression.

Previous studies have shown that only some members of the Ras subfamily, such as H-Ras, Rap1A, Rap1B, R-Ras3, Ral, and now Rit (2, 19, 25, 29, 59, 63, 77), play a role in NGF-dependent PC12 cell differentiation, while other Ras-related GTPases, such as RheB, TC21, and R-Ras, do not display this biological activity (26, 46, 54). Indeed, Ral and RheB appear to antagonize neuronal differentiation in PC12 cells (19, 26). More importantly, whereas the expression of a number of activated Ras-related GTPases can promote PC12 cell differentiation, only dominant-inhibitory mutants of H-Ras, R-Ras3, and Rit have been found to inhibit NGF-dependent neurite outgrowth (29, 63). Constitutive activation of the ERK cascade appears to be a critical aspect of the differentiation cascades induced by each of these activated GTPases (29, 59, 72, 77). The importance of ERK signaling in PC12 differentiation is further supported by studies in which activated versions of Raf and MEK can mimic, at least in part, the effects of activated Ras and NGF (11, 71). Moreover, inhibition of the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway inhibits stimulus-induced neurite outgrowth. Thus, neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells requires the activity of MEK and ERK. Previous studies have shown, at least in NIH 3T3 cells, that Rit does not activate these kinase pathways (49, 51).