Abstract

AIM

To evaluate the feasibility, safety and peri- and postoperative outcomes of robotic single-site supracervical hysterectomy (RSSSH) for benign gynecologic disease.

METHODS

We report 3 patients who received RSSSH for adenomyosis of the uterus from November 2015 to April 2016. We evaluated the feasibility, safety and outcomes among these patients.

RESULTS

The mean surgical time was 244 min and the estimated blood loss was 216 mL, with no blood transfusion necessitated. The docking time was shortened gradually from 30 to 10 min. We spent 148 min on console operation. Manual morcellation time was also short, ranging from 5 to 10 min. The mean hospital stay was 5 d. Lower VAS pain score was also noted. There is no complication during or after surgery.

CONCLUSION

RSSSH is feasible and safe, incurs less postoperative pain and gives good cosmetic appearance. The technique of in-bag, manual morcellation can avoid tumor dissemination.

Keywords: Robotic surgery, Single-site, Supracervical hysterectomy, Single port, Subtotal hysterectomy

Core tip: Robotic single-site surgery (RSS) is feasible and safe in performing supracervical hysterectomy for benign gynecologic disease. Less pain and cosmetic value are important advantages of RSS. Manual morcellation can be done through single port setting.

INTRODUCTION

The first laparoscopic subtotal hysterectomy (LSH) was reported in 1991[1]. Retaining the cervix may preserve sexual, urinary and bowel function[2].

LSH is approached in the same manner as total laparoscopic hysterectomy (LTH). After uterine vessels are secured, the cervix is transected at the level of internal os. However, the ascending branch of uterine vessel is sometimes hard to approach. During transection, severe bleeding may occur. Amputation of the cervix is also a time-consuming procedure. The loop is also designed for cervical amputation and could save 80% of the time required for performing this procedure[3]. Retrieval of uterine corpus after the transection was achieved by mechanical or manual morcellation through an extended abdominal port[4]. The mean surgical time of LSH ranged from 70 min to 134 min[5]. Complications and outcomes are comparable with those of LTH. Above all, the technique involved in LSH is more difficult than LTH because of the time required for amputation of cervix.

Robotic assisted hysterectomy (RAH) has been increased from 0.5% in 2007 to 9.5% in 2010[6,7]. Although RAH is a safe approach to hysterectomy, but the longer surgical time required[8-10]. Compared to open surgery, RAH provides advantages for reduced length of hospital stay and blood transfusions[11].

Laparo-endoscopic single-site surgery (LESS) offered a new way to perform minimally invasive gynecological surgery[12-14]. The advantages of LESS included less post-operative pain, lower dosage of analgesic required[13], greater cosmetic satisfaction[14], lower morbidity and comparable outcomes compared with those of standard laparoscopic surgery[14,15]. Nevertheless, LESS involves technical challenges such as loss of port triangulation, clashing of instruments and long learning curve. Robotic single-site surgery (RSS) may provide advantages to overcome these shortages[16,17].

Here we described supracervical hysterectomy performed with single-site da Vinci Surgical System (Si version, Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, United States) in three patients affected by adenomyosis of the uterus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Three women presented with adenomyosis of the uterus complicated with menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea. Two patients had previous history of abdominal surgery. One woman had anemia (Hb: 10.3 g/dL) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients received robot single-site supracervical hysterectomy

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | Mean |

| Diagnosis | Adenomyosis | Adenomyosis | Adenomyosis | |

| Age (yr) | 44 | 43 | 48 | 45 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.5 | 23.6 | 26.6 | 24.2 |

| Previous surgery | Partial oophorecotmy | Nil | C/S | |

| Largest diameter of uterus (cm) | 8 | 10 | 11.9 | 10 |

| Total op time (min) | 200 | 233 | 300 | 244.3 |

| Docking time (min) | 30 | 20 | 10 | 20 |

| Console time (min) | 120 | 160 | 165 | 148.3 |

| Morcellated time (min) | 5 | 5 | 10 | 6.7 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 100 | 300 | 250 | 216.7 |

| VAS (1 h) | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.7 |

| VAS (24 h) | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| VAS (48 h) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.7 |

| Hospital stay (d) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Complication | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

VAS: Pain score; BMI: Body mass index.

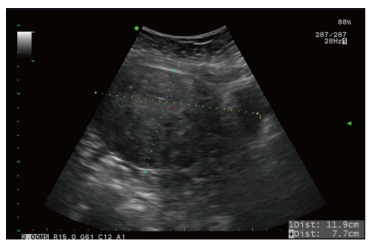

Abdominal ultrasound was performed for all patients; their maximum diameters of uterus were listed in Table 1. Figure 1 shows the uterus of the largest diameter of 11.9 cm with the suspected lesion of adenomyosis located at the posterior uterine wall.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound of adenomyosis of uterus. The largest diameter of uterus measured was 11.9 cm.

The patients were then scheduled for robotic-assisted supracervical hysterectomy. The single-port device is a multichannel non-reusable specific port with space for four cannulas and an insufflation valve. A target anatomy arrow indicator is marked on the cannula. Two 25-cm curved cannulas for robotic instruments, one cannula for the high-definition three-dimensional endoscope, and one 5-mm assistant cannula were used in the surgery.

The uterine manipulator was placed to adjust the uterine position. After catching the bilateral skin along the umbilicus with two Allis clamps, a 2-cm midline umbilical skin incision was made. Through this incision, a wound retractor (Lagis, Taichung, Taiwan) was introduced into the abdominal cavity, then a single-site port (da Vinci Surgical System) was introduced into the abdominal cavity grasped by an atraumatic clamp through the wound retractor.

The patient was placed supine in lithotomy position with 30° Trendelenburg position, and the robotic patient cart was positioned between the patient’s legs. Then the robotic arms were opened in the opposite position. The 30° endoscope was placed in camera trocar and a watchful inspection of total abdominal cavity was performed.

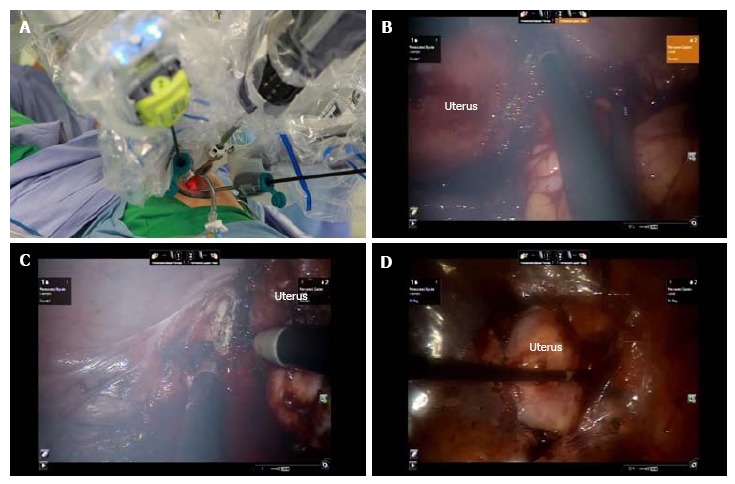

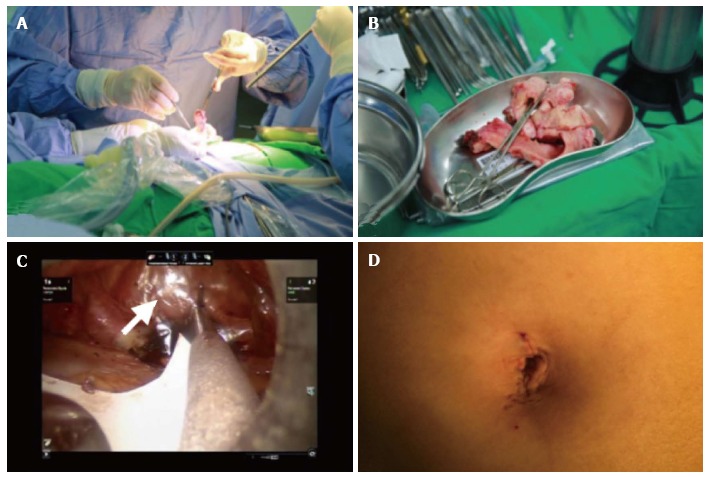

Then the other three cannulas were inserted through the port and their positions were adjusted according to the scope view and mark. The remaining cannula was placed in front of the uterus and then held still to allow docking. Finally, robotic instruments including fenestrated bipolar and hook unipolar instruments were introduced (Figure 2A). One Veress needle (COVIDIEN) was inserted at suprapubic region under direct vision by endoscope for evacuation the smoke. After cutting both right and left endocervical regions (Figure 2B and C), the amputated uterus was rolled and placed into a tissue bag (Cook, Figure 2D). Then the robot was undocked and the tissue bag was grasped to the umbilical port using an assistant port grasper. Then the uterus was manually morcellated from the umbilical wound (Figure 3A) and all morcellated pieces were placed onto a plate (Figure 3B). Then one sheet of Seprafilm was cut into four pieces and placed with or without docking robot arms onto surgical sites to prevent adhesion (Figure 3C). After all robotic procedures were completed, the umbilical wound was closed using interrupted 0 Vicryl for the fascia layer and 3-0 Vicryl for the subcutaneous layer (Ethicon, Figure 3D).

Figure 2.

Intraoperative view of supracervical hysterectomy. A: Placement of robotic trocars using a single-site device; B: Cutting right cervical region; C: Cutting left cervical region; D: Amputated uterus placed into tissue bag.

Figure 3.

Intraoperative view of manual morcellation of the uterus and the placement of seprafilm. A: Manual morcellation of uterus through the single-site wound; B: Morcellated uterus; C: Seprafilm placed onto surgical sites (arrow); D: Postoperative umbilical scar.

Statistical analysis

Statistics using Student’s t-test was performed when compare pain score of the two groups, and the differences between the groups were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

The mean operative time was 244 min and the estimated blood loss was 216 mL (Table 1), with no blood transfusion necessitated. The docking time was shortened gradually from 30 to 10 min. We spent 148 min on console operation. Manual morcellation time was also short, ranging from 5 to 10 min. The post-operative course was uneventful and all patients were discharged 3 d after operation. The VAS pain score was 3.7, 3.0 and 0.7 at 1, 24 and 48 h, respectively. The mean hospital stay was 4 d. The surgical specimens conformed adenomyosis of the uterus. There is no complication during or after surgery.

DISCUSSION

Single-site surgery has become popular due to improved cosmetic appearance, multiple incisions avoided, and minimal post-operative pain and recovery time[13,14]. Nevertheless, LESS surgery is characterized by longer surgical time and technical challenge. Robotic single-site surgery (RSS) is the same as LESS, but the instrument was more ergonomic compared with other single-site methods[18,19]. In our experience, RSS supracervical hysterectomy (SH) is a valid alternative to laparoscopic and standard robotic SH and provides the same surgical outcome.

There is only one study report on the RSSSH experience in gynecology[20]. However, there is no detailed information regarding RSSSH except the number of patients while there are several reports on RSS hysterectomy (RSSH)[16,18,21-23]. RSSH was first reported in 2011[23] and concluded to be feasible offering several advantages such as smaller scar, less pain and the same outcome compared with standard robotic surgery[23]. Moreover, in preclinical models of human cadavers, the RSS technique is effective and reproducible in various gynecological surgeries[24].

There is a more surgical time in RSSSH than in RSSH. The total surgical time is 134 min in RSSH but 244 min in RSSSH[19]. The cause of more surgical time may be attributed to our initial experience and the type of surgery performed. The pelvic adhesiolysis have also contributed to longer operating time. A lot of surgical time was spent in the endocervical ring cutting. The cutting efficiency of robot hook is not efficient. Coagulate the bleeding caused by cutting the endocervical ring is also time consuming. However, we assume the surgical time can be shortened after more surgical experiences.

There is more blood loss after RSSSH than after RSSH[19]. The mean blood loss is 50 mL in RSSH but 240 mL in RSSSH. The cause of greater blood loss may be attributed to our initial experience and the type of surgery performed. In RSSH, the vagina is cut after securing the uterine vessels. However, in RSSSH, the ascending branch of uterine vessels cannot be easily secured using a bipolar instrument. Therefore, after cutting the bilateral endocervical region, bleeding can sometimes be vigorous. This condition is the same for LESS supracervical hysterectomy[25].

The advantage of RSS is less post-operative pain, thus necessitating less pain control[13,14]. This study also demonstrated these advantages. The VAS pain score was 3.7, 3.0 and 0.7 at 1, 24 and 48 h, respectively. In contrast, the VAS in LESS hysterectomy was 5.6, 3.7 and 2.2 at 1, 24 and 48 h, respectively (Table 2)[13], indicating significantly lower VAS pain score in RSSSH than in LESS hysterectomy at 1 and 48 h (P < 0.05). Infiltration wound with ropivacaine or other long-acting local anesthetics also provide good pain control[19,26].

Table 2.

Comparison of postoperative pain

| Time | LESS hysterectomy (n = 36) | RSSSH (n = 3) | P value |

| VAS pain score | |||

| 0-2 h | 5.68 ± 2.11 | 3.7 ± 0.6 | < 0.05 |

| 24 h | 3.75 ± 1.61 | 3.0 ± 1.0 | > 0.05 |

| 48 h | 2.25 ± 1.59 | 0.7 ± 1.6 | < 0.05 |

LESS: Laparoendoscopic single-site surgery; RSSSH: Robot single-site supracervical hysterectomy; VAS: Visual analog scale.

The mean hospital stay in this study is 4 d. Nevertheless, the hospital stay is only 3 d in the previous study[19]. The long hospital stay in our study is due to the health insurance in our country. The insurance offers the patient can stay in hospital for 4 d.

Power morcellation had been widely used in laparoscopic surgery to speed removal of specimen[27]. However, owing to the risk of leiomyosarcoma dissemination after power morcellation, removal of specimen in a bag was suggested[28,29]. Therefore, techniques for safe specimen removal have been reported[30]. We also developed a technique of manual morcellation[31]. In this study, we used the same technique for placing the specimen into a tissue bag and for manual morcellation through the single-port wound. This morcellation method is relatively safe without tumor cell or tissue dissemination.

The use of Seprafilm as adhesion barrier was approved by the FDA in 1996. However, Seprafilm is seldom used in laparoscopic surgery because it easily breaks and sticks[32]. We applied a simple technique (using wet gauze and paper roll) for rapid and safe placement of Seprafilm onto the surgical sites[33].

Another problem encountered during RSS is surgical smoke that could influence the vision. With RSS using both unipolar and bipolar energies, there is no additional port for passage of smoke in the single-port device. To overcome this problem, a small Veress needle is used for smoke release, thus achieving good vision outcome.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that RSSSH is feasible and safe in gynecologic patients. Less postoperative pain and greater cosmetic satisfaction were the major advantages of RSSSH. The technique of in-bag, manual morcellation could avoid tumor dissemination. Nevertheless, randomized study and the outcome of long-term follow-up are still needed in the future.

COMMENTS

Background

Minimally invasive surgery has been popular in gynecologic surgery. Therefore, despite conventional multi-port laparoscopic surgery, laparoscopic single-site surgery (LESS) emerges since 2009. However, there are some technical difficulties and instrument design hurdling the progress of LESS. Nevertheless, Robotic single-site surgery (RSSS) solves the technical and instrument problems in LESS.

Research frontiers

RSSS is in its beginning stage. Although there are several papers discussing the RSSS, there is still a lot of space to improve the RSSS on supracervical hysterectomy (SH). The authors attempted to use RSSS to perform SH and to test if RSSS is a feasible and safe method to perform SH.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The present study demonstrated RSSSH is a feasible and safe method for the patients with adenomyosis of the uterus.

Applications

The data in this study suggested that RSSSH could be a feasible and safe modality for patients with adenomyosis of the uterus.

Terminology

Adenomyosis of the uterus is a condition of endometrial glands presented in the myometrium and enlarged of the uterus. The symptoms of adenomyosis are including dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia that cause the major reason for women receiving hysterectomy.

Peer-review

The authors investigated the feasibility of RSSSH for adenomyosis of the uterus and found that this approach is safe and acceptable in the management of the similar patients in the future based on the analysis of outcome from the 3 patients.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Buddhist Tzu Chi General Hospital.

Informed consent statement: This study is a retrospective chart review and approved by IRB. Therefore, no informed consent was needed.

Conflict-of-interest statement: There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: October 10, 2016

First decision: December 1, 2016

Article in press: March 2, 2017

P- Reviewer: Blumenfeld Z, Cosmi E, Rovas L, Wang PH S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

References

- 1.Semm K. [Hysterectomy via laparotomy or pelviscopy. A new CASH method without colpotomy] Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1991;51:996–1003. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1026252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cipullo L, De Paoli S, Fasolino L, Fasolino A. Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy compared to total hysterectomy. JSLS. 2009;13:370–375. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallwiener M, Taran FA, Rothmund R, Kasperkowiak A, Auwärter G, Ganz A, Kraemer B, Abele H, Schönfisch B, Isaacson KB, et al. Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (LSH) versus total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH): an implementation study in 1,952 patients with an analysis of risk factors for conversion to laparotomy and complications, and of procedure-specific re-operations. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;288:1329–1339. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-2921-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donnez O, Jadoul P, Squifflet J, Donnez J. A series of 3190 laparoscopic hysterectomies for benign disease from 1990 to 2006: evaluation of complications compared with vaginal and abdominal procedures. BJOG. 2009;116:492–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giep BN, Giep HN, Hubert HB. Comparison of minimally invasive surgical approaches for hysterectomy at a community hospital: robotic-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy, laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy and laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy. J Robot Surg. 2010;4:167–175. doi: 10.1007/s11701-010-0206-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright JD, Ananth CV, Lewin SN, Burke WM, Lu YS, Neugut AI, Herzog TJ, Hershman DL. Robotically assisted vs laparoscopic hysterectomy among women with benign gynecologic disease. JAMA. 2013;309:689–698. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smorgick N, Patzkowsky KE, Hoffman MR, Advincula AP, Song AH, As-Sanie S. The increasing use of robot-assisted approach for hysterectomy results in decreasing rates of abdominal hysterectomy and traditional laparoscopic hysterectomy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289:101–105. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-2948-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paraiso MF, Ridgeway B, Park AJ, Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Falcone T, Einarsson JI. A randomized trial comparing conventional and robotically assisted total laparoscopic hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:368.e1–368.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarlos D, Kots L, Stevanovic N, von Felten S, Schär G. Robotic compared with conventional laparoscopic hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:604–611. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318265b61a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lönnerfors C, Reynisson P, Persson J. A randomized trial comparing vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy vs robot-assisted hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Neill M, Moran PS, Teljeur C, O’Sullivan OE, O’Reilly BA, Hewitt M, Flattery M, Ryan M. Robot-assisted hysterectomy compared to open and laparoscopic approaches: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;287:907–918. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2681-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fanfani F, Fagotti A, Scambia G. Laparoendoscopic single-site surgery for total hysterectomy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;109:76–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong MK, Wang JH, Chu TY, Ding DC. Laparoendoscopic single-site hysterectomy with Ligasure is better than conventional laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2014;3:78–81. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SM, Park EK, Jeung IC, Kim CJ, Lee YS. Abdominal, multi-port and single-port total laparoscopic hysterectomy: eleven-year trends comparison of surgical outcomes complications of 936 cases. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291:1313–1319. doi: 10.1007/s00404-014-3576-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li M, Han Y, Feng YC. Single-port laparoscopic hysterectomy versus conventional laparoscopic hysterectomy: a prospective randomized trial. J Int Med Res. 2012;40:701–708. doi: 10.1177/147323001204000234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Escobar PF, Fader AN, Paraiso MF, Kaouk JH, Falcone T. Robotic-assisted laparoendoscopic single-site surgery in gynecology: initial report and technique. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:589–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Hachem L, Andikyan V, Mathews S, Friedman K, Poeran J, Shieh K, Geoghegan M, Gretz HF. Robotic Single-Site and Conventional Laparoscopic Surgery in Gynecology: Clinical Outcomes and Cost Analysis of a Matched Case-Control Study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:760–768. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cela V, Freschi L, Simi G, Ruggiero M, Tana R, Pluchino N. Robotic single-site hysterectomy: feasibility, learning curve and surgical outcome. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2638–2643. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bogliolo S, Mereu L, Cassani C, Gardella B, Zanellini F, Dominoni M, Babilonti L, Delpezzo C, Tateo S, Spinillo A. Robotic single-site hysterectomy: two institutions’ preliminary experience. Int J Med Robot. 2015;11:159–165. doi: 10.1002/rcs.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheib SA, Fader AN. Gynecologic robotic laparoendoscopic single-site surgery: prospective analysis of feasibility, safety, and technique. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:179.e1–179.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vizza E, Corrado G, Mancini E, Baiocco E, Patrizi L, Fabrizi L, Colantonio L, Cimino M, Sindico S, Forastiere E. Robotic single-site hysterectomy in low risk endometrial cancer: a pilot study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2759–2764. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2922-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mereu L, Carri G, Khalifa H. Robotic single port total laparoscopic hysterectomy for endometrial cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:644. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.07.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nam EJ, Kim SW, Lee M, Yim GW, Paek JH, Lee SH, Kim S, Kim JH, Kim JW, Kim YT. Robotic single-port transumbilical total hysterectomy: a pilot study. J Gynecol Oncol. 2011;22:120–126. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2011.22.2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Escobar PF, Kebria M, Falcone T. Evaluation of a novel single-port robotic platform in the cadaver model for the performance of various procedures in gynecologic oncology. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;120:380–384. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hobson DT, Imudia AN, Al-Safi ZA, Shade G, Kruger M, Diamond MP, Awonuga AO. Comparative analysis of different laparoscopic hysterectomy procedures. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285:1353–1361. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-2140-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joshi GP, Bonnet F, Kehlet H. Evidence-based postoperative pain management after laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:146–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsai HW, Ocampo EJ, Huang BS, Chen SA. Effect of semi-simultaneous morcellation in situ during laparoscopic myomectomy. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2015;4:132–136. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin KH, Ho-Jun S, Chen CL, Torng PL. Effect of tumor morcellation during surgery in patients with early uterine leiomyosarcoma. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2015;4:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park JY, Park SK, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim YT, Nam JH. The impact of tumor morcellation during surgery on the prognosis of patients with apparently early uterine leiomyosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levine DJ, Berman JM, Harris M, Chudnoff SG, Whaley FS, Palmer SL. Sensitivity of myoma imaging using laparoscopic ultrasound compared with magnetic resonance imaging and transvaginal ultrasound. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:770–774. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu MY, Ding DC, Chu TY, Hong MK. “Contain before transection, contain before manual morcellation” with a tissue pouch in laparoendoscopic single-site subtotal hysterectomy. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2016;5:178–181. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chuang YC, Lu HF, Peng FS, Ting WH, Tu FC, Chen MJ, Kan YY. Modified novel technique for improving the success rate of applying seprafilm by using laparoscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:787–790. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong MK, Ding DC. Seprafilm application method in laparoscopic surgery. JSLS. 2017:In press. doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2016.00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]