Abstract

AIM

To investigate the effect of a low-FODMAP diet on irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)-like symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

METHODS

This was a randomised controlled open-label trial of patients with IBD in remission or with mild-to-moderate disease and coexisting IBS-like symptoms (Rome III) randomly assigned to a Low-FODMAP diet (LFD) or a normal diet (ND) for 6 wk between June 2012 and December 2013. Patients completed the IBS symptom severity system (IBS-SSS) and short IBD quality of life questionnaire (SIBDQ) at weeks 0 and 6. The primary end-point was response rates (at least 50-point reduction) in IBS-SSS at week 6 between groups; secondary end-point was the impact on quality of life.

RESULTS

Eighty-nine patients, 67 (75%) women, median age 40, range 20-70 years were randomised: 44 to LFD group and 45 to ND, from which 78 patients completed the study period and were included in the final analysis (37 LFD and 41 ND). There was a significantly larger proportion of responders in the LFD group (n = 30, 81%) than in the ND group (n = 19, 46%); (OR = 5.30; 95%CI: 1.81-15.55, P < 0.01). At week 6, the LFD group showed a significantly lower median IBS-SSS (median 115; inter-quartile range [IQR] 33-169) than ND group (median 170, IQR 91-288), P = 0.02. Furthermore, the LFD group had a significantly greater increase in SIBDQ (median 60, IQR 51-65) than the ND group (median 50, IQR 39-60), P < 0.01.

CONCLUSION

In a prospective study, a low-FODMAP diet reduced IBS-like symptoms and increased quality of life in patients with IBD in remission.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Web-based management, Irritable bowel syndrome, Low-FODMAP diet

Core tip: This is one of the first randomized controlled studies showing that low-FODMAP diet had ameliorative effect on irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)-like symptoms in a Danish inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) population in remission. The IBD quality of life were also improved on the same diet. Based on the results of this study, a low-FODMAP diet could be recommended for IBD patients in remission who are experiencing IBS-like symptoms. The diet requires guidance from a dietician for closely monitoring of the nutritional adequacy with dietary restriction.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are gastrointestinal disorders (GI) that include ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). The disease course of IBD is intermittent, with periods of remission and activity[1]. Even though periods of remission enhance a patient’s well-being, IBD patient will often still suffer from various functional symptoms which may affect their quality of life (QOL)[2]. Some IBD specific symptoms overlap symptoms similar to irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) such as bloating, abdominal pain, altered bowel habits (diarrhoea and/or constipation) and abdominal distension[3,4].

Approximately 40% of IBD patients may suffer from IBS-like symptoms[5,6]. It has been suggested that certain diets, such as one with increased dietary fiber or a lactose free diet[7,8], can influence IBS-like symptoms. However, the benefits of these diets have not been verified. Recently, it has been shown that FODMAPs (Fermentable, Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides and Polyols), which are poorly absorbed in the small intestine and fermented by bacteria in the colon, can trigger symptoms such as bloating, abdominal pain, alter bowel habits (diarrhoea and/or constipation), and gas in sensitive individuals[9-11].

A diet containing high quantities of FODMAPs has been shown to increase GI symptoms[10,12], while a low-FODMAP diet (LFD) has been shown to ameliorate symptoms in IBS patients[13-17] and in IBD patients with IBS[18,19]. In a retrospective study from 2009, consisting of 72 IBD patients that had previously been on a LFD, Gearry et al[18], demonstrated significant (56% of patients) improvement of functional overall abdominal symptoms (pain, bloating, wind and diarrhoea) in patients on a LFD. In a recent prospective study of 88 patients with IBD in remission with functional-like gastrointestinal symptoms (FGS) on a LFD, Prince et al[19] demonstrated a satisfactory relief of the FGS at week 5 when compared to week 0 (16% vs 78%, P < 0.001). Furthermore, a significant improvement of overall and individual symptoms such as stool consistency and frequency in this study has been observed. However, prospective randomized controlled data on the effects of a LFD on IBD patients are lacking.

The aim of this study was to investigate whether a LFD would alter IBS-like symptoms and improve the quality of life among IBD patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This was a randomized, open-label 6-wk study with the primary aim of evaluating the effect of a LFD on IBS-like symptoms in IBD patients with quiescent or mild-to-moderate activity where the primary end-point was the number of patients achieving a 50-point reduction in IBS-SSS after six weeks, and secondarily, whether a LFD could improve QOL. All patients were allocated to either a treatment group (LFD group) or a control group on a normal habitual diet (ND group). A person not involved in the study generated the random allocation sequence and numbered the envelopes.

Study subjects

Patients were recruited from a tertiary hospital in Copenhagen, Denmark between June 2012 and November 2013.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) IBD patients in remission or with mild-to-moderate disease activity and coexisting IBS-like symptoms (Rome III criteria)[20,21] with a baseline IBS-SSS (IBS-symptom severity score) of at least 75 points[22]; and (2) IBD patients on maintenance therapy with 5-aminosalic acid (5-ASA), azathioprine (AZA) or biologicals or a combination of these, on a stable dose (no dose adjustments or additional medications were taken by patients in the 4 wk prior to entry in the study). Furthermore, no dose adjustments or additional medications were allowed during the study.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) IBD patients with moderate-to-severe relapse (SCCAI > 6, HBI > 12) at inclusion; (2) steroid treatment less than four weeks before inclusion; and (3) vegetarians or patients with coeliac disease, lactose intolerance (lactose blood and lactose gene test), allergies, or those on an alternative diet regimen.

Outcome measurements

IBS severity: Overall IBS-like symptoms were measured by the internationally validated IBS-SSS[22]. The IBS-SSS score is structured as a five-subscore visual analog scale (VAS), which can be self-administered or completed by a physician. It evaluates the intensity of IBS-like symptoms during the preceding 10 d with regards to the following subscores: abdominal pain intensity and duration, abdominal distension, stool frequency and consistency, and interference with life in general. Each of the five subscores generates a maximum score of 100 points, which gives a maximum IBS-SSS total score of 500 points. A minimum of 50 points reduction in total IBS-SSS during the study was considered an improvement[22]. A minimum of 10 points reduction or more of each of the five subscores was also considered an improvement[13,15,18].

IBD activity: Disease activity of UC was measured by the Simple Clinical Colitis Index (SCCAI)[23]. A SCCAI score of ≤ 2 defines remission, > 2 mild-to-moderate, and > 6 severe disease activity.

Disease activity in CD was measured by the Harvey Bradshaw Index (HBI)[24]. A score < 5 defines remission, 5-7 mild activity, 8-12 moderate, and > 12 severe disease activity.

Additionally, inflammatory biomarkers, faecal calprotectin (FC) and C-reactive protein (CRP), were used to measure disease activity at 0 and 6-wk of the study. Cut-off values of FC for remission was ≤ 100 μg/g in UC[25,26] and ≤ 200 μg/g in CD[27-29]. A CRP cut-off value of ≤ 10 mg/L was used to define remission[28,30].

Additional measurements: Disease-related quality of life was assessed using the Short IBD Questionnaire (SIBDQ)[31] and the IBS Quality of Life (IBS-QOL)[32] questionnaire. A self-constructed food frequency questionnaire (FFQ)[33] was used to measure adherence to the diets. It contains lists of the most commonly consumed high-FODMAP foods adapted to a Danish population, Supplementary Table 1 (Supplemental Digital Content 1). Patients’ FFQ was used to calculate their FODMAP intake in gram per day (g/d).

Dietary procedure

At baseline, all patients underwent a 30-min, appointment for dietary assessment (including nutritional status) with nutritionists and a dietary intake was obtained from all patients using the FFQ. Thereafter, patients in the intervention group were given an individual one-hour counseling session about the LFD. Detailed information regarding the LFD was provided, including handouts with recipes, tips, and meal plans. Patients in the ND group were requested to follow an unchanged habitual diet during the 6-wk. At the end of the study all LFD patients had a 30-min follow up counseling session with the nutritionists, in which they were reintroduced to the high-FODMAP foods that had been restricted or forbidden during the 6-wk study period.

Web-based application: www.ibs.constant-care.dk

The web-based application www.ibs.constant-care.dk[16,34,35] was specifically designed for IBS and IBD patients in order to facilitate self-management with the registration of IBS-like symptoms and to monitor the severity of their disease and QOL. At baseline, all patients underwent a medical history assessment, including prior treatment, and were introduced (30-min session) to the web-based questionnaires (IBS-SSS, IBS-QOL) and non-web-based questionnaires (IBDQ, SCCAI, HBI), all completed by participants at 0 and 6-wk. Detailed information on the application and patient registration are shown in Supplementary Figures 1 (Supplemental Digital Content 2) and 2 (Supplemental Digital Content 3).

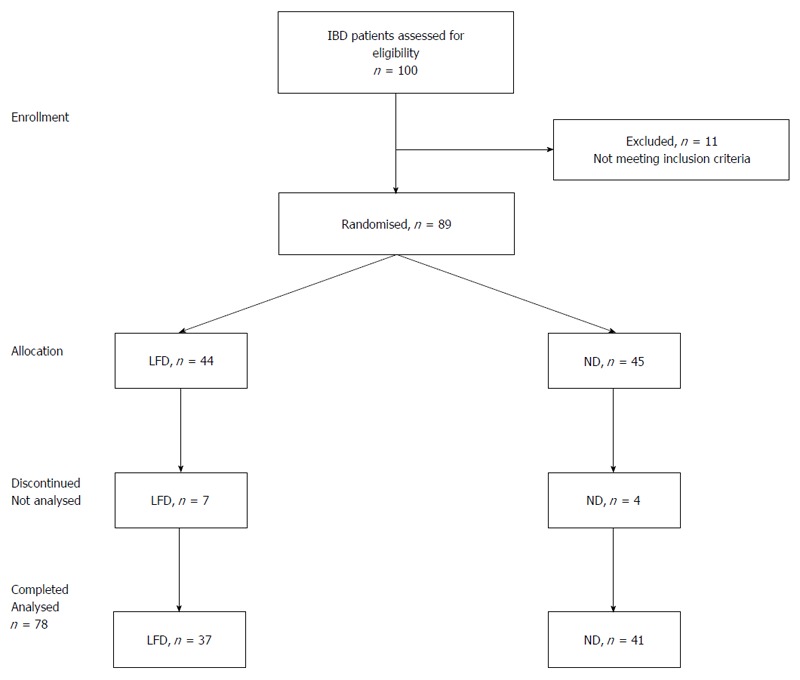

Figure 1.

Enrollment and progress of patients in the study. IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; ND: Normal diet; LFD: Low-FODMAP diet.

Sample size determination

Sample size was estimated to be 80 patients in total: 40 patients in the ND group and 40 patients in the intervention group. The assumed standard deviation (SD) of 6-wk IBS-SSS scores and the smallest relevant clinical difference between groups were 80 and 50, respectively[21,36]. The standard deviation for IBS-SSS was based on a previous study[34] α and β were set to 5 % and 20 %, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed, including frequency distributions for categorical data and means, medians/interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables. Per protocol (PP) and intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses were performed on primary end-point. Inflammatory biomarkers (CRP, FC) were analyzed as geometric means and coefficient of variations (CVs) were added. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for comparing paired samples (0-wk vs 6-wk) within each treatment group, testing for a decrease in IBS-SSS score within each treatment group. The Mann-Whitney U test was performed to compare treatment groups with respect to a decrease in IBS-SSS score. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Corelation analysis between outcomes was performed using the non-parametric Spearman’s rank correlation.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the impact on change/response of the total IBS-SSS and IBS-SSS subscores of the following factors/covariates: baseline IBS-SSS, diet, age ≤ 40 years, BMI, diagnosis, gender, IBD duration ≤ 5 years, smoking, prior surgery, IBD maintenance therapy (5-ASA, thiopurines and biologicals) and disease activity.

All data were processed in SPSS software Version 20 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc. Care. NC, Unites States).

Ethical considerations

The Ethical Committee, Denmark (protocol number H-2-2012-05/38987) approved the study. All patients included in this study signed an informed consent document.

RESULTS

Patients flow and baseline characteristics

A total of 100 IBD patients with coexisting IBS-like symptoms were screened for their eligibility in the study, of which 89 patients [61 (69%) with UC and 28 (31%) with CD] were randomly assigned to either the LFD (n = 44) or ND (n = 45) groups. Eleven patients (12%) discontinued the study one week after enrolment, seven (8%) patients in the LFD and four (4%) in the ND group, due to difficulty with the diet in the LFD group and a lack of compliance with the web program in the ND group. The final group comprised 78 patients (LFD, n = 37 vs ND, n = 41) and were included in a PP analysis. Additionally, all 89 patients were included in an ITT analysis of primary outcome.

There were not significant differences in demographic and disease characteristics data between groups apart from there being more smokers and prior surgery observed in the LFD group. The flow of the patients in the study is shown in Figure 1. Baseline characteristics of patients by treatment group are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients

| Low-FODMAP diet, n = 44 | Normal diet, n = 45 | P value | |

| Male/Female | 12 (27)/32 (73) | 10 (23)/35 (77) | 0.64 |

| Age, median (range) | 40 (20-70) | 41 (24-69) | 0.55 |

| Body mass index, median (range) | 25 (18-39) | 24 (18-52) | 0.44 |

| Smoking | 0.01 | ||

| Current | 8 (18) | 2 (4) | |

| Former | 19 (43) | 12 (28) | |

| Never | 17 (39) | 30 (68) | |

| IBD diagnosis type | 0.93 | ||

| Ulcerative colitis (UC) | 30 (68) | 31 (69) | |

| Crohn’s disease (CD) | 14 (32) | 14 (31) | |

| UC extent | 0.34 | ||

| E1, proctitis | 7 (23) | 11 (36) | |

| E2, left side | 15 (50) | 10 (32) | |

| E3, extensive | 8 (27) | 10 (32) | |

| CD location | 0.51 | ||

| L1, small bowel | 4 (29) | 3 (21) | |

| L2, colonic | 4 (29) | 7 (50) | |

| L3, ilea-colonic | 6 (42) | 4 (29) | |

| CD behavior | 0.13 | ||

| B1, inflammatory | 6 (43) | 11 (79) | |

| B2, stricturing | 6 (43) | 2 (14) | |

| B3, penetrating | 2 (14) | 1 (7) | |

| IBD duration, median (range) | 7 (1-40) | 5 (1-39) | 0.41 |

| IBD disease activity (yes) | 6 (14%) | 7 (16%) | 0.52 |

| UC disease activity (SCCAI) | 3 (1-4) | 2 (1-4) | 0.75 |

| CD disease activity (HBI) | 7 (3-8) | 5 (4-11) | 0.61 |

| IBS severity (IBS-SSS) | 210 (190-270) | 245 (180-320) | 0.40 |

| IBS-quality of life | 73 (19-99) | 77 (30-98) | 0.25 |

| Short-IBD-quality of life (SIBDQ) | 47 (42-55) | 50 (40-57) | 0.88 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L), median (range) | 2 (2-35) | 2 (2-52) | 0.32 |

| Faecal calprotectin (μg/L), median (range) | 50 (2-1259) | 39 (2-1600) | 0.28 |

| FODMAPs (g/d), median (range) | 24 (9-81) | 26 (4-58) | 0.53 |

| Surgery prior study | 11 (25) | 2 (4) | 0.01 |

| Medication: Yes/No | 34/10 | 38/7 | 0.41 |

| 5-ASA/Sulphasalazine | 23 (52) | 25 (55) | |

| Azathioprine (AZA)/Methotrexate | 4 (9) | 7 (15)/1 (2) | |

| Biologicals ± AZA | 5 (11) | 4 (9) |

Data are expressed as n (%), median (IQR: Interquartile range). IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; IBS: Irritable bowel disease; SSS: Symptom severity scale; SCCAI: Simple clinical colitis index; HBI: Harvey Bradshaw index.

IBS-like symptoms (IBS-SSS)

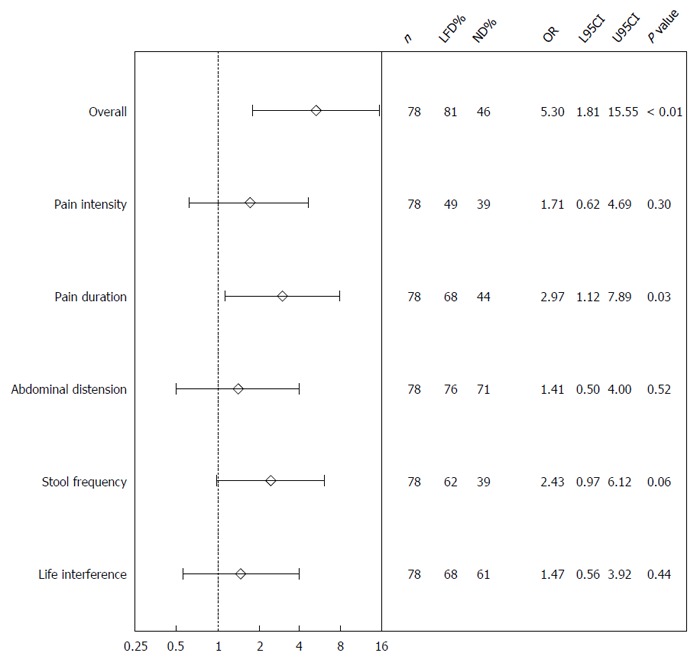

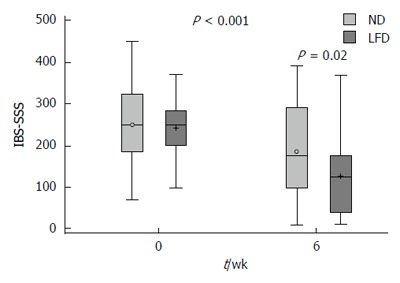

A total of 30 (81%) patients were responders in the LFD group as opposed to 19 (46%) in the ND group, P < 0.01. The response rates in IBS-SSS subscores among IBD patients are illustrated in Figure 2. At 6-wk, a significantly lower IBS-SSS score was observed in the LFD group (median IBS-SSS 115, IQR 33-169) as compared to the ND group (median IBS-SSS 170, IQR 91-288), P = 0.02 (Table 2, Figure 3). Adjusted for baseline characteristics, logistic regression analysis identified IBS-SSS LFD/ND treatment Odds ratio (OR) (OR = 5.30, 95%CI: 1.81-15.55, P < 0.01) as clearly associated with the overall IBS-SSS response (Figure 2). The analysis of IBS-SSS subscores showed that patients on a LFD had a significantly greater reduction in pain duration as compared to those on a ND (OR = 2.97, 95%CI: 1.12-7.89, P = 0.03) as well as a trend towards an improvement in stool frequency and consistency (OR = 2.43, 95%CI: 0.97-6.12, P = 0.06) (Figure 2). IBD duration ≤ 5 years was associated with pain intensity reduction (OR = 0.23, 95%CI: 0.08-0.65, P < 0.01) and less interference with life in general (OR = 0.33, 95%CI: 0.12-0.88, P = 0.03), Supplementary Table 2 (Supplemental Digital Content 4).

Figure 2.

Logistic regression analysis of the total irritable bowel syndrome-severity score system response and its subscores for the normal diet and low FODMAP diet groups at 6-wk. IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome; SSS: Symptom severity score; ND: Normal diet; LFD: Low-FODMAP diet; N: Number; L95CI: Lower 95% confidence interval; U95CI: Upper 95% confidence interval.

Table 2.

Results of main outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease patients on low-FODMAP diet

| Number | Week 0 | Week 6 | P value | |

| Irritable Bowel Syndrome-Symptom Severity System (IBS-SSS) | ||||

| Low-FODMAP | 37 | 210 (190-270) | 115 (33-169) | < 0.001 |

| Normal diet | 41 | 245 (180-320) | 170 (91-288) | < 0.001 |

| 0.021 | ||||

| Simple Clinical Colitis Index (SCCAI) | ||||

| Low-FODMAP | 24 | 3 (1-4) | 1 (0-3) | 0.04 |

| Normal diet | 29 | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-4) | 0.98 |

| 0.021 | ||||

| Harvey and Bradshaw Index (HBI) | ||||

| Low-FODMAP | 9 | 7 (3-8) | 3 (1-5) | 0.05 |

| Normal diet | 12 | 5 (4-11) | 6 (3-9) | 0.25 |

| 0.091 | ||||

| Irritable Bowel Syndrome Quality of Life (IBS-QOL) | ||||

| Low-FODMAP | 36 | 73 (19-99) | 78 (18-99) | < 0.01 |

| Normal diet | 41 | 77 (30-98) | 81 (26-99) | 0.30 |

| 0.091 | ||||

| Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ) | ||||

| Low-FODMAP | 34 | 47 (42-55) | 60 (51-65) | < 0.01 |

| Normal diet | 40 | 50 (40-57) | 50 (39-60) | 0.54 |

| < 0.011 | ||||

P: Mann-Whitney U test comparison of change in outcomes between treatment groups at 6-wk. All data are presented as median (IQR: Interquartile range). P: Wilcoxon signed rank test, comparison of paired samples 0 vs 6-wk for all subjects; All IBS-QOL results on 0-100 scale (0 worst, 100 best).

Figure 3.

Box plot of irritable bowel syndrome-severity score system crude data in means ± SD, medians (range) for the normal diet and low FODMAP diet groups at 0 vs 6-wk. IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome; SSS: Symptom severity score; ND: Normal diet; LFD: Low-FODMAP diet.

The subgroup analysis of IBS-SSS according to disease activity (Table 3) showed that IBD patients in remission had a significantly better response on LFD (median IBS-SSS 105, IQR 26-167) than on ND (median IBS-SSS 175, IQR 77-298), P < 0.01. No difference in IBS-SSS was observed in IBD patients with mild-to-moderate disease activity, LFD (median IBS-SSS 169, IQR 105-332) vs ND (median IBS-SSS 140, IQR 96-211, P = 0.53). Furthermore, CD patients on LFD had a significantly greater IBS-SSS reduction (median IBS-SSS 58, IQR 18-173) than those on ND (median IBS-SSS 220, IQR 57-357), P = 0.02, while no impact of diet in UC was seen, LFD (median IBS-SSS 120, IQR 36-170) vs ND (median IBS-SSS 141, IQR 52-263, P = 0.37) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of irritable bowel syndrome-symptom severity system response in subgroups of inflammatory bowel disease patients on low FODMAP

| Number | Week 0 | Week 6 | P value | |

| Ulcerative colitis (UC) | ||||

| UC | 55 (71) | 220 (190-300) | 124 (40-198) | < 0.01 |

| LFD | 26 (47) | 225 (187-260) | 120 (36-170) | < 0.01 |

| ND | 29 (53) | 220 (185-315) | 141 (52-263) | < 0.01 |

| 0.371 | ||||

| Crohn’s disease (CD) | ||||

| CD | 23 (29) | 245 (170-320) | 170 (56-294) | < 0.01 |

| LFD | 11 (48) | 210 (160-320) | 58 (18-173) | 0.02 |

| ND | 12 (52) | 250 (172-382) | 220 (57-357) | 0.54 |

| 0.021 | ||||

| UC vs CD, P = 0.241 | ||||

| IBD-Remission by SCCAI/HBI | ||||

| Remission | 65 (83) | 230 (175-305) | 140 (39-212) | < 0.01 |

| LFD | 31 (48) | 220 (170-250) | 105 (26-167) | < 0.01 |

| ND | 34 (52) | 242 (177-322) | 175 (77-298) | < 0.01 |

| < 0.011 | ||||

| IBD Mild-to-Moderate Activity by SCCAI/HBI | ||||

| Activity | 13 (17) | 210 (200-350) | 140 (103-252) | 0.53 |

| LFD | 6 (46) | 210 (194-391) | 169 (105-332) | 0.17 |

| ND | 7 (54) | 260 (200-330) | 140 (96-211) | 0.06 |

| 0.531 | ||||

| Remission vs Activity, P < 0.011 | ||||

| FC-remission (≤ 100 μg/g UC, ≤ 200 μg/g CD), n = 53 | ||||

| Remission | 53 (73) | 220 (179-305) | 113 (34-225) | < 0.01 |

| LFD | 25 (47) | 220 (174-305) | 60 (29-169) | < 0.01 |

| ND | 28 (53) | 230 (180-307) | 174 (66-298) | < 0.01 |

| 0.061 | ||||

| FC-activity (> 100 μg/g UC; > 200 μg/g CD), n = 20 | ||||

| Activity | 20 (27) | 250 (204-330) | 160 (110-211) | < 0.01 |

| LFD | 11 (55) | 210 (200-250) | 157 (95-198) | 0.04 |

| ND | 9 (45) | 320 (230-360) | 170 (103-291) | 0.03 |

| 0.501 | ||||

| FC-Remission vs FC-Activity, P = 0.291 | ||||

| CRP-remission (< 10 mg/L), n = 75 | ||||

| Remission | 75 (96) | 230 (180-320) | 140 (50-211) | < 0.01 |

| LFD | 35 (47) | 210 (187-260) | 114 (30-169) | < 0.01 |

| ND | 40 (53) | 248 (180-320) | 176 (78-288) | < 0.01 |

| < 0.011 | ||||

| CD, prior surgery (bowel/ileo-coecal resections), n = 13/23 (57%) | ||||

| LFD | 11 | 225 (178-302) | 10 (32-223) | < 0.01 |

| ND | 2 | - | - | |

P: Mann-Whitney U test comparison of change in outcomes between treatment groups at 6-wk. All data are presented as median (IQR: Interquartile range), n (%) (- only 2 cases). P: Wilcoxon signed rank test, comparison of paired samples within each treatment group. IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome; SSS: Severity score system; IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; LFD: Low FODMAP diet; ND: Normal Diet.

IBS-SSS response according to disease activity measured by FC (total n = 73) (Table 3) showed that patients experiencing FC-remission (< 100 μg/g in UC, < 200 μg/g in CD) n = 53/73 (73%) had a better response to LFD (median IBS-SSS 60, IQR 29-169) than to a ND (median IBS-SSS 174, IQR 66-298), P = 0.06. In those with FC-activity (FC > 100 μg/g in UC and > 200 μg/g in CD), n = 20/73 (27%) both LFD and ND patients responded significantly at 6-wk, with no significant difference observed between groups LFD (median IBS-SSS 150, IQR 95-198) vs ND (median IBS-SSS 170, IQR 103-291), P = 0.49.

IBS-SSS response according to disease activity measured by CRP (Table 3) showed that patients experiencing CRP-remission (< 10 mg/L) (96%), had a significant response in both the LFD and ND groups at 6-wk, with a larger response in the LFD group (median IBS-SSS 114, IQR 30-169) vs ND group (median IBS-SSS 176, IQR 78-288), P < 0.01.

The IBS-SSS response rates in different subgroups of IBD patients on the LFD and ND are shown in Supplementary Table 3 (Supplemental Digital Content 5). No significant difference in response rates between UC 36 (66%) vs CD patients 13 (57%), P = 0.31 was observed.

As with PPT analysis, ITT responder analysis of all 89 patients showed a statistically significant increase of the response rates of IBS-SSS in LFD as compared to that of ND (OR = 3.34, 95%CI: 1.28-8.30, P = 0.01).

Disease activity in UC and CD

In total, 65 (83%) patients were in remission and 13 (17%) had mild-to-moderate activity upon entry to the study (Table 1). A statistically significant reduction in SCCAI change was observed for the LFD in UC patients (median 1, IQR 0-3) as compared to the ND (median 2, IQR 1-4), P = 0.02 [Table 2, Supplementary Figure 3, (Supplemental Digital Content 6)]. In patients with CD no significant reduction of HBI was observed in those on a LFD (median 3, IQR 1-5) vs ND (median 6, IQR 3-9), P = 0.09 (Table 2). A significant correlation between HBI and IBS-SSS improvement was found (rho = 0.4, P = 0.005). Furthermore, among UC patients a significant correlation between reduction of SCCAI and improvement in IBDQ (r = -0.53, P < 0.001) was observed. However, in CD patients the correlation between HBI and IBDQ was not significant (rho = 0.38, P = 0.09).

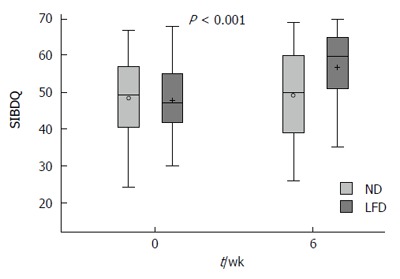

Quality of life

At wk-6, a statistically significant improvement in SIBDQ was observed in those on a LFD (median 60, IQR 51-65) when compared to those on a ND (median 50, IQR 39-60), P < 0.01 (Table 2, Figure 4). IBS-QOL did not improve significantly in either the LFD (median 78, IQR 51-65) or ND (median 81 IQR 26-99) groups, P = 0.09 (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Box plot of short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire crude data in means ± SD, medians (range) for the normal diet and low FODMAP groups at 0 vs 6-wk. SIBDQ: Short inflammatory bowel disease quality of life; ND: Normal diet; LFD: Low-FODMAP diet.

C-reactive protein

Seventy-five (96%) and 74 (95%) patients had C-reactive protein (CRP) levels lover than 10 mg/L at week 0 and 6, respectively. There was a significant difference in geometric mean CRP in the ND group at 6-wk (2.6; 95%CI: 2.1-3.3) as compared to 0-wk (2.2; 95%CI: 1.8-2.5), P = 0.04. While no difference in mean CRP in the LFD group was observed at 6-wk (2.8; 95%CI: 2.2-3.5) compared 0-wk (2.7; 95%CI: 2.2-3.2), P = 0.57. Likewise, no significant difference between the LFD and ND groups with regards to CRP change at the end of the study was observed, P = 0.23, Supplementary Table 4 (Supplemental Digital Content 7).

FC

Seventy-three (94%) patients collected FC at the baseline. Of these, 53 (73%) at baseline and 51 (69%) at 6-wk had FC levels < 100 μg/g among UC patients or < 200 μg/g among CD patients. There was no significant difference in geometric mean FC in either the LFD 6-wk (mean 53; 95%CI: 30-93) vs 0-wk (mean 65; 95%CI: 37-113), P = 0.75 or ND 6-wk (mean 46; 95%CI: 27-81) vs ND 0-wk (mean 44; 95%CI: 23-83) vs, P = 0.46. Likewise, no significant difference between the LFD and ND groups with regards to FC change at the end of the study was observed, P = 0.41, Supplementary Table 4 (Supplemental Digital Content 7).

Adherence to the diets

The quantity of FODMAPs in g/d was determined for all 78 patients (100%) at 0-wk and in 73 patients (94%) at 6-wk. At baseline, there was no significant difference in FODMAP g/d ingested by ND (median 26, range 4-58) vs LFD patients (median 24, range 9-81), P = 0.53. At the end of the study, the LFD patients had a significantly lower FODMAP g/d intake (median 2, range 0-49) than the ND patients (median 24, range 2-68), P = 0.04, Supplementary Table 5 (Supplemental Digital Content 8).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge this study is the first prospective, randomized study conducted in a Danish population investigating the impact of a LFD among IBD patients in remission or with mild-to-moderate disease activity with IBS-like symptoms. This study showed a greater response rate for patients on a LFD and a substantial reduction in overall IBS-like symptoms measured by IBS-SSS in patients on a LFD compared to a ND by the end of the study (6-wk).

Subgroup analysis of this study in IBS-SSS response indicates that LFD is beneficial for IBD patients in remission. Since only six IBD patients had activity in their disease while being on a LFD in this study the question of the efficacious role of a LFD in patients with mild-to-moderate-activity remains inconclusive and further studies are needed.

Subgroup analysis of IBS-SSS showed that CD patients benefited most from the LFD, many of whom had a history of bowel surgery. UC patients, on the other hand, did not show any considerable improvement on IBS-SSS even though they were greater in number than CD patients. UC treated with a LFD did, however, show improvement in the disease activity (SCCAI). Furthermore, a strong correlation between SCCAI and IBDQ is shown in this study and demonstrates that UC patients are likely to benefit from a LFD.

The results of this study are consistent with the retrospective results of an Australian study with regards to overall IBS-like symptoms and separate IBS-SSS subscores[18]. The authors demonstrated a considerable reduction of diarrhoea (58% for UC and 46% for CD). A newly published prospective study from England, based on 88 IBD patients, also supports the effect of a LFD in treating IBS-like symptoms in IBD patients[19]. This study found a substantial relief in functional-like gastrointestinal symptoms, stool type and frequency; however, due to the design they were not able to form conclusions as to the effect of a LFD on disease activity.

A validated IBS-SSS questionnaire was used for assessment of severity of IBS-like symptoms in this study. However, it seems that the IBS-SSS questionnaire might be suited to monitoring IBS-like symptoms in CD than in UC since the subgroup analysis only showed a response among CD patients. One explanation for this could be that two-fifths of the questions on the IBS-SSS score address abdominal pain and this is the main symptom in CD, while only one-fifths of questions of the IBS-SSS concerns stool habits and these are especially relevant in UC. Perhaps the Australian method, using a self-developed GI rating VAS questionnaire on specific and general symptoms would be more accurate for measuring IBS-like symptoms in IBD patients[9,12,13,17].

IBS-like symptoms could be triggered by FODMAPS, which are osmotic molecules that can cause diarrhea, flatulence, and bloating (gas production) that may lead to abdominal pain[10]. Data from this study suggest that a LFD may affect disease activity indices (that measure functional symptoms) by altering IBS-like symptoms such as abdominal pain and stool consistency/frequency, overlapping symptoms included in the HBI and SCCAI activity indices[37-40]. Although no mucosal endoscopic evaluation in this study was performed, inflammatory biomarkers (CRP, FC) were used to assess disease activity in the study. Results from this study did not show that the LFD affects inflammatory biomarkers (CRP, FC), suggesting that the dietary interventions did not improve inflammation either.

Additionally, the effect of the LFD on the microbiome and metabolites will also be important when evaluating the nutritional adequacy of the LFD since many IBD patients have a dysbiotic microbiota with for instance, a decreased Faecalibacterium prausnitzii[41]. Halmos et al[42] have demonstrated that a LFD can decrease the abundance of bifidobacteria and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in IBS patients. The nutritional adequacy, including weight gain or loss while on the restrictive LFD, needs to be examined in future studies since both parameters are essential for many IBD patients. Based on these findings the authors recommend a LFD for short-term use only in managing IBS symptoms, after which, high FODMAP foods should be reintroduced. As such, reintroduction of FODMAPs after a 6-wk LFD likewise be encouraged among IBD patients due to a lack of evidence regarding the long-term effects and consequences of the diet[9,43].

Besides improvements in IBS-like symptoms, this study also demonstrated a substantial improvement of the QOL in patients on a LFD for six weeks, which can partly be explained by the ranked correlations between SIBDQ and IBS-SSS/SCCAI. In a retrospective long-term follow-up study of 43 IBD patients on a LFD, Maagaard et al[44] demonstrated an improvement in their Copenhagen IBS disease course type from a more chronic intermittent course to a milder, indolent one.

The aim of using a web-based approach for monitoring IBS-like symptoms is to involve patients in the self-management of their disease[34]. The web-based symptom monitoring approach in this study is a kind of diary in which the IBS-like symptoms and data on IBS quality of life were registered at least at the baseline and the end of the study. This approach may have had an impact on IBS-like symptoms independent of dietary intervention, as previously reported by Pedersen et al[16]. Nevertheless, web monitoring was used in both groups of patients, and thus one can assume that the differences observed between the LFD and ND groups are attributable to their specific diets.

The strength of this study is that it is the first prospective, randomized study performed in a European population. The sample size is relatively large, and the results are significant, based on relevant questionnaires. The study evaluates subjective clinical symptoms, QOL and objective markers of inflammation.

A major limitation of this study is that the groups were not blinded with regard to their diets and therefore it was possible for the ND patients to search for information about the topic on the internet and subsequently change their eating habits accordingly. While a blinded diet is possible in dietary trials, as shown by Halmos et al[15], these interventions are difficult to carry out as they require special facilities, are time consuming, expensive and do not represent standard clinical practice. Although the diet in our study was not blinded, the results of FFQ (LFD group consumed less FODMAPS compared to the ND), confirm that patients had an optimal adherence to the diet, obtained by a tight diet control by nutritionists during the study period.

A LFD may be difficult to follow without guidance from a dietician to help individualize and optimize the diet in order to obtain a greater symptom response[45]. In addition, guidance from a dietician ensures better nutritional adequacy during the use of the restrictive LFD.

Finally, the heterogeneity of IBD patients makes it difficult to distinguish IBS-like symptoms from IBD and considering the significant placebo effects (diet and web) in this study, both make it difficult to draw any firm conclusions[40].

In conclusion, this study supports the claim that LFD intervention has a beneficial effect among IBD patients in remission with IBS-like symptoms, as the results from this study show amelioration of symptoms and improvement in the quality of life. Based on these results a dietician-assisted LFD could be recommended in the short-term for IBD patients in remission who are experiencing IBS-like symptoms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank dieticians Lisbeth Jensen and Mette Simonsen (Herlev Hospital) for their assistance with the follow-up of low-FODMAP diet in some patients after the study ended.

COMMENTS

Background

Diet low in FODMAPs has shown to be beneficial in reducing symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Furthermore, it has as well been shown to ameliorate IBS-like symptoms in patients suffering from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in one retrospective and one prospective study, however, no randomized controlled trail (RCT) has ever substantiated the beneficial effect of the diet for IBD.

Research frontiers

The study demonstrates the effect of the low FODMAP diet in IBD patients in remission with IBS-like symptoms in a RCT.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This is the first RCT investigating the effect of the low FODMAP diet on IBD patients in remission with co-existing IBS symptoms. The study supports the current evidence that the diet ameliorates IBS symptoms and improves quality of life for IBD patients.

Applications

Low-FODMAP may be recommended for patients with IBD in remission and co-existing IBS-like symptoms, however, further studies are need in order to specify how this diet regime should be implemented with focus on time on the diet, gut microbiota and nutritional status.

Terminology

Fermentable, oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) are poorly absorbed and rapidly fermentable carbohydrates and sugar alcohols triggering abdominal symptoms. IBS-like symptoms in IBD patients are presented by abdominal symptoms such as abdominal distension, bloating, abdominal pain and diarrhoea. IBS-severity scoring system (IBS-SSS) is an international validated score used for the measuring of the severity of the IBS symptoms. www.ibs.constant-care.dk is a web-based database for monitoring of IBS symptoms and quality of life constructed to be used by both IBS patients and IBD patients.

Peer-review

The author showed in their study that low-FODMAP diet reduces irritable bowel symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in remission while the question of the efficacious role of LFD in patients with mild-to-moderate-activity remains inconclusive. Further studies are required to demonstrate possible changes in inflammatory cytokines, microbiota profile, and SCFAs, which may have consequences for gut health with the low FODMAP diet. In addition to appropriate FODMAP manipulation, a dietician will assess and closely monitor nutritional adequacy with dietary restriction and manage as appropriate, including patients in whom nutrient absorption is impaired or dietary intake is altered.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Denmark

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: The study was approved by Ethics Committee of Science, Denmark (protocol H-2-2012-05/38987).

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data sharing statement: Data set are available from the corresponding author (natalia.pedersen@regionh.dk). The Danish Data Protection Agency approved the study design for ensuring the protection of the data. The presented data are anonymized and the risk of identification is low. No additional data are available.

Peer-review started: November 17, 2016

First decision: December 24, 2016

Article in press: March 20, 2017

P- Reviewer: Day AS, Torres MI S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Burisch J, Pedersen N, Čuković-Čavka S, Brinar M, Kaimakliotis I, Duricova D, Shonová O, Vind I, Avnstrøm S, Thorsgaard N, et al. East-West gradient in the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe: the ECCO-EpiCom inception cohort. Gut. 2014;63:588–597. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minderhoud IM, Oldenburg B, Wismeijer JA, van Berge Henegouwen GP, Smout AJ. IBS-like symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in remission; relationships with quality of life and coping behavior. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:469–474. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000020506.84248.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jonefjäll B, Strid H, Ohman L, Svedlund J, Bergstedt A, Simren M. Characterization of IBS-like symptoms in patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical remission. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:756–e578. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keohane J, O’Mahony C, O’Mahony L, O’Mahony S, Quigley EM, Shanahan F. Irritable bowel syndrome-type symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a real association or reflection of occult inflammation? Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1788, 1789–1794; quiz 1795. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halpin SJ, Ford AC. Prevalence of symptoms meeting criteria for irritable bowel syndrome in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1474–1482. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simrén M, Axelsson J, Gillberg R, Abrahamsson H, Svedlund J, Björnsson ES. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease in remission: the impact of IBS-like symptoms and associated psychological factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:389–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moayyedi P, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, Soffer EE, Spiegel BM, Ford AC. The effect of fiber supplementation on irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1367–1374. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herfarth HH, Martin CF, Sandler RS, Kappelman MD, Long MD. Prevalence of a gluten-free diet and improvement of clinical symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1194–1197. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Staudacher HM, Lomer MC, Anderson JL, Barrett JS, Muir JG, Irving PM, Whelan K. Fermentable carbohydrate restriction reduces luminal bifidobacteria and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Nutr. 2012;142:1510–1518. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.159285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ. Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: The FODMAP approach. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:252–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ. Personal view: food for thought--western lifestyle and susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. The FODMAP hypothesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1399–1409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halmos EP, Muir JG, Barrett JS, Deng M, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. Diarrhoea during enteral nutrition is predicted by the poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrate (FODMAP) content of the formula. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:925–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Roest RH, Dobbs BR, Chapman BA, Batman B, O’Brien LA, Leeper JA, Hebblethwaite CR, Gearry RB. The low FODMAP diet improves gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:895–903. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shepherd SJ, Parker FC, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Dietary triggers of abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: randomized placebo-controlled evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:765–771. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:67–75.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedersen N, Vegh Z, Burisch J, Jensen L, Ankersen DV, Felding M, Andersen NN, Munkholm P. Ehealth monitoring in irritable bowel syndrome patients treated with low fermentable oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyols diet. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6680–6684. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i21.6680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Staudacher HM, Whelan K, Irving PM, Lomer MC. Comparison of symptom response following advice for a diet low in fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs) versus standard dietary advice in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24:487–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2011.01162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gearry RB, Irving PM, Barrett JS, Nathan DM, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. Reduction of dietary poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates (FODMAPs) improves abdominal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease-a pilot study. J Crohns Colitis. 2009;3:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prince AC, Myers CE, Joyce T, Irving P, Lomer M, Whelan K. Fermentable Carbohydrate Restriction (Low FODMAP Diet) in Clinical Practice Improves Functional Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:1129–1136. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drossman DA. Rome III: the new criteria. Chin J Dig Dis. 2006;7:181–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-9573.2006.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–1491. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Francis CY, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:395–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.142318000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jowett SL, Seal CJ, Phillips E, Gregory W, Barton JR, Welfare MR. Defining relapse of ulcerative colitis using a symptom-based activity index. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:164–171. doi: 10.1080/00365520310000654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Best WR. Predicting the Crohn’s disease activity index from the Harvey-Bradshaw Index. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:304–310. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000215091.77492.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guardiola J, Lobatón T, Rodríguez-Alonso L, Ruiz-Cerulla A, Arajol C, Loayza C, Sanjuan X, Sánchez E, Rodríguez-Moranta F. Fecal level of calprotectin identifies histologic inflammation in patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical and endoscopic remission. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1865–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedersen N, Thielsen P, Martinsen L, Bennedsen M, Haaber A, Langholz E, Végh Z, Duricova D, Jess T, Bell S, et al. eHealth: individualization of mesalazine treatment through a self-managed web-based solution in mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:2276–2285. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lehmann FS, Burri E, Beglinger C. The role and utility of faecal markers in inflammatory bowel disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2015;8:23–36. doi: 10.1177/1756283X14553384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D’Haens G, Ferrante M, Vermeire S, Baert F, Noman M, Moortgat L, Geens P, Iwens D, Aerden I, Van Assche G, et al. Fecal calprotectin is a surrogate marker for endoscopic lesions in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2218–2224. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith LA, Gaya DR. Utility of faecal calprotectin analysis in adult inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6782–6789. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i46.6782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vermeire S, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P. Laboratory markers in IBD: useful, magic, or unnecessary toys? Gut. 2006;55:426–431. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.069476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drossman D, Morris CB, Hu Y, Toner BB, Diamant N, Whitehead WE, Dalton CB, Leserman J, Patrick DL, Bangdiwala SI. Characterization of health related quality of life (HRQOL) for patients with functional bowel disorder (FBD) and its response to treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1442–1453. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drossman DA, Patrick DL, Whitehead WE, Toner BB, Diamant NE, Hu Y, Jia H, Bangdiwala SI. Further validation of the IBS-QOL: a disease-specific quality-of-life questionnaire. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:999–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barrett JS, Gibson PR. Development and validation of a comprehensive semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire that includes FODMAP intake and glycemic index. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:1469–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pedersen N, Andersen NN, Végh Z, Jensen L, Ankersen DV, Felding M, Simonsen MH, Burisch J, Munkholm P. Ehealth: low FODMAP diet vs Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16215–16226. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pedersen N. EHealth: self-management in inflammatory bowel disease and in irritable bowel syndrome using novel constant-care web applications. EHealth by constant-care in IBD and IBS. Dan Med J. 2015;62:B5168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kennedy T, Jones R, Darnley S, Seed P, Wessely S, Chalder T. Cognitive behaviour therapy in addition to antispasmodic treatment for irritable bowel syndrome in primary care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;331:435. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38545.505764.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farrokhyar F, Marshall JK, Easterbrook B, Irvine EJ. Functional gastrointestinal disorders and mood disorders in patients with inactive inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence and impact on health. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:38–46. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000195391.49762.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fukuba N, Ishihara S, Tada Y, Oshima N, Moriyama I, Yuki T, Kawashima K, Kushiyama Y, Fujishiro H, Kinoshita Y. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome-like symptoms in ulcerative colitis patients with clinical and endoscopic evidence of remission: prospective multicenter study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:674–680. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.898084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gracie DJ, Ford AC. IBS-like symptoms in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2015;8:101–109. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S58153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lahiff C, Safaie P, Awais A, Akbari M, Gashin L, Sheth S, Lembo A, Leffler D, Moss AC, Cheifetz AS. The Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) is similarly elevated in patients with Crohn’s disease and in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:786–794. doi: 10.1111/apt.12262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Casén C, Vebø HC, Sekelja M, Hegge FT, Karlsson MK, Ciemniejewska E, Dzankovic S, Frøyland C, Nestestog R, Engstrand L, et al. Deviations in human gut microbiota: a novel diagnostic test for determining dysbiosis in patients with IBS or IBD. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:71–83. doi: 10.1111/apt.13236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Halmos EP, Christophersen CT, Bird AR, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. Diets that differ in their FODMAP content alter the colonic luminal microenvironment. Gut. 2015;64:93–100. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Staudacher HM, Whelan K. Altered gastrointestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome and its modification by diet: probiotics, prebiotics and the low FODMAP diet. Proc Nutr Soc. 2016;75:306–318. doi: 10.1017/S0029665116000021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maagaard L, Ankersen DV, Végh Z, Burisch J, Jensen L, Pedersen N, Munkholm P. Follow-up of patients with functional bowel symptoms treated with a low FODMAP diet. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:4009–4019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i15.4009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Halmos EP, Gibson PR. Dietary management of IBD--insights and advice. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:133–146. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]