Abstract

Introduction

The purpose of this study was to perform a direct comparison of several existing risk-stratification tools for localized prostate cancer in terms of their ability to predict for biochemical failure-free survival (BFFS). Two large databases were used and an external validation of two recently developed nomograms on an independent cohort was also performed in this analysis.

Methods

Patients who were treated with external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) and/or brachytherapy for localized prostate cancer were selected from the multi-institutional Genitourinary Radiation Oncologists of Canada (GUROC) Prostate Cancer Risk Stratification (ProCaRS) database (n=7974) and the Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM) validation database (n=2266). The primary outcome was BFFS using the Phoenix definition. Concordance index (C-index) reported from Cox proportional hazards regression using 10-fold cross validation and decision curve analysis (DCA) were used to predict BFFS.

Results

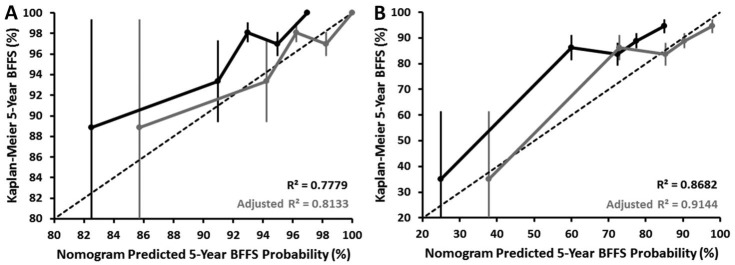

C-index identified Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment (CAPRA) score and ProCaRS as superior to the historical GUROC and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) risk-stratification systems. CAPRA modeled as five and three categories were superior to GUROC and NCCN only for the CHUM database. C-indices for CAPRA score, ProCaRS, GUROC, and NCCN were 0.72, 0.72, 0.71, and 0.72, respectively, for the ProCaRS database, and 0.66, 0.63, 0.57, and 0.60, respectively, for the CHUM database. However, many of these comparisons did not demonstrate a clinically meaningful difference. DCA identified minimal differences across the different risk-stratification systems, with no system emerging with optimal net benefit. External validation of the ProCaRS nomograms yielded favourable calibrations of R2=0.778 (low-dose rate [LDR]-brachytherapy) and R2=0.868 (EBRT).

Conclusions

This study externally validated two ProCaRS nomograms for BFFS that may help clinicians in treatment selection and outcome prediction. A direct comparison between existing risk-stratification tools demonstrated minimal clinically significant differences in discriminative ability between the systems, favouring the CAPRA and ProCaRS systems. The incorporation of novel prognostic variables, such as genomic markers, is needed.

Introduction

Risk-stratification for localized prostate cancer can assist clinicians in selecting the most appropriate treatment for their patients based on pertinent clinical and pathological factors. A variety of pre-treatment tools have been reported based primarily on the prognostic power of initial prostate-specific antigen (PSA), biopsy Gleason score, and clinical T stage.1 One of the first systems, and arguably still the most widely used, was proposed by D’Amico et al, which stratified patients into three groups based on their risk of biochemical failure after either radical prostatectomy or external beam radiotherapy (EBRT).2 Health organizations, such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), have also published classification systems for prostate cancer. The NCCN guideline adds very low-risk and very high-risk groups to the traditional three-group classification.3

Common risk-stratification tools, such as the D’Amico and NCCN classifications, can help clinicians predict treatment outcomes. One limitation of these tools is that they assume patients within each risk group are essentially similar and do not distinguish, for instance, between Gleason 3 + 4 vs. 4 + 3 or by the number of intermediate or high-risk features. Consequently, several new risk-stratification systems that incorporate these clinical variables have been developed. One such system developed by the Genitourinary Radiation Oncologists of Canada (GUROC), known as the Prostate Cancer Risk Stratification (ProCaRS) is based on an updated version of a risk-stratification system first published in 2001.4,5

Also, clinical nomograms have been developed to predict treatment outcomes prior to radiotherapy. For instance, the GUROC have published two separate nomograms to predict for biochemical failure after exclusive low-dose rate (LDR)-brachytherapy and exclusive EBRT.4 Several studies have demonstrated that nomograms can yield accurate models with predictability comparable to risk-stratification models.6–9

Deciding which risk-stratification model to use in the clinical setting can be difficult with so many different, but related models in existence. To our knowledge, no direct comparison between the ProCaRS and other risk-stratification models has yet been published.

The present study aimed to compare the different risk-stratification systems in two large databases, with an overarching hypothesis being that newer risk-stratification systems would demonstrate more favourable predictability compared to older systems. An additional goal of this work was to validate the GUROC ProCaRS nomograms for LDR-brachytherapy only and for EBRT only in a single-institution database.

Methods

Patient selection

The CHUM database (validation database)

The Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM) database has been described previously.10 The database contains retrospectively collected data from 2266 patients treated with conventionally fractionated or hypofractionated EBRT, LDR-brachytherapy, high-dose rate (HDR)-brachytherapy, or combined therapy for primary localized prostate cancer. All patients were treated between 1994 and 2015. Patients receiving radical prostatectomy as primary treatment were excluded. Institutional research ethics board approval was obtained from CHUM prior to study initiation.

The GUROC ProCaRS database

The GUROC ProCaRS database is a retrospective, multi-institutional database containing data from 7974 patients with localized prostate cancer. All patients received LDR-brachytherapy, HDR-brachytherapy, conventionally fractionated EBRT, or combination. Similarly, patients receiving radical prostatectomy as primary treatment were excluded. All patients were treated between 1994 and 2010 at one of four participating Canadian institutions (British Columbia Cancer Agency [n=3771], Princess Margaret Hospital [n=1752], McGill University Health Centre [n=194], and L’Hotel Dieu de Québec [n=2257]). Additional details pertaining to the creation of the GUROC ProCaRS database have been previously published.11

Clinical outcomes

Biochemical failure-free survival (BFFS) was selected as the primary endpoint for this investigation, calculated as time from initiation of radiotherapy to date of last followup and/or biochemical failure (according to the ASTRO II Phoenix consensus definition of a PSA increase of 2 ng/mL above the nadir PSA), and/or death, whichever came first.12 Benign PSA bounces were classified as technical biochemical failures only, and were adjusted using a quality assurance procedure previously reported.11,13,14

Risk-stratification systems

This investigation examined the ability of four distinct prognostic risk-stratification systems to predict for BFFS.

The Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment (CAPRA) tool classifies patients on a continuous scale from 0–10 based on: (1) age at diagnosis (≥50 [one point]); (2) PSA at diagnosis measured in ng/mL (6.1–10 [one point]; 10.1–20 [two points]; 20.1–30 [three points]; >30 [four points]); (3) Gleason score (secondary pattern 4 or 5 [one point]; primary pattern 4 or 5 [three points]); T-stage (T3a [one point]); and percentage of positive biopsy cores (>34 % [one point]).15 For this analysis, CAPRA was examined as a continuous 10-point scale (CAPRA score) as a three-risk category system (CAPRA-3) defining risk as low (0–2), intermediate (3–5), and high (6–10); and as a novel five-risk category system (CAPRA-5) defining risk as low (0–2), low-intermediate (3), high-intermediate (4–5), high (6–7) and very high (8–10).16

The GUROC system groups patients into three risk categories: low (T1–T2a and PSA ≤10 ng/mL and Gleason ≤6); intermediate (T1–T2 and PSA ≤20 ng/mL and Gleason ≤7 and not otherwise low-risk); and high (T3–T4 or PSA >20 ng/mL or Gleason 8–10).11

The ProCaRS (ProCaRS-5) system groups patients into five risk categories according to the GUROC system: low (T1–T2a and PSA ≤10 ng/mL and Gleason ≤6); low-intermediate (T1–T2 and PSA ≤20 ng/ml and PSA ≤10 ng/mL or [PSA >10 ng/mL and T1–T2a or Gleason ≤6]); high-intermediate (T1–T2 and PSA ≤20 ng/mL and [PSA >10 ng/mL and T2b/c or Gleason 7]); high (T3–T4 or [PSA >20 ng/mL and PSA <30 ng/mL or Gleason 8–10] and positive core percentage <87.5%); and very high ([T3–T4 or Gleason 8–10 or PSA >20 ng/mL] and [PSA ≥30 ng/mL or positive core percentage ≥87.5%]).11

The NCCN risk stratification system groups patients into fve risk categories: very low (T1c and Gleason ≤6 and PSA <10 ng/mL and <3 positive core biopsies); low (T1–T2a and Gleason ≤6 and PSA <10 ng/mL); intermediate (T2b–T2c or Gleason 7 or PSA=10–20 ng/mL); high (T3a or Gleason 8–10 or PSA >20 ng/mL); and very high (T3b–T4 or Gleason primary pattern 5).3

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated for baseline patient, tumour, and treatment characteristics for all patients and compared between databases (ProCaRS [n=7974], CHUM [n=2266]) using the Chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, two-sample T-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test, as appropriate. Univariable Cox proportional hazards regression was performed for BFFS for each risk-stratification variable, separately by database. Kaplan-Meier estimates of BFFS were generated for each risk-stratification variable for the CHUM database only, and compared using the Log-rank test.

The concordance index (C-index) was calculated and reported from Cox proportional hazards regression for BFFS using 10-fold cross-validation for all possible risk-stratification variables, as described previously (CAPRA score, CAPRA-5, CAPRA-3, ProCaRS, GUROC, and NCCN).17 Decision curve analysis (DCA) was performed, measured at five years following initiation of radiotherapy for BFFS. CAPRA score, CAPRA-5, CAPRA-3, ProCaRS, GUROC, and NCCN were compared to the scenarios of all patients having no recurrence (“none”) and all patients having recurrence (“all”).18

External validation of the previously published ProCaRS nomograms to predict five-year BFFS (as defined previously) for LDR-brachytherapy only and EBRT only was performed using the CHUM database.4 This was performed using calibration plots of nomogram-predicted probability compared to corresponding Kaplan-Meier five-year BFFS estimates, respectively, and restricted to patients with a minimum of six months of followup, as reported previously.4 All statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS institute, Cary, NC, U.S.) and the R language environment for statistical computing version 3.3.0 (open source, www.r-project.org), using two-sided statistical testing at the 0.05 significance level.

Results

Baseline patient characteristics of both databases are shown in Table 1. Biochemical failure was observed in 134 patients (6%) and death in 102 patients (5%) with a corresponding five-year BFFS of 92.9% for the CHUM database (Supplementary Table 1; available at www.cuaj.ca). Clinical outcomes and patient characteristics for the ProCaRS database have been described in detail previously.11,19 Median followup was 3.67 years for the CHUM database compared to 6.57 years in the ProCaRS database (p<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline tumour, patient, and treatment characteristics for all patients stratified by database

| Characteristic | n | ProCaRS database (n=7974) | n | CHUM database (n=2266) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD, median (min, max) | 7970 | 66.5 ± 7.4 | 2241 | 67.0 ± 6.7 | 0.002 |

| 67.0 (34.0, 88.0) | 68.0 (44.0, 87.0) | ||||

| Baseline PSA (ng/mL), median (min, max) | 7844 | 2252 | <0.001 | ||

| 6.8 (0.1, 250.0) | 6.4 (0.2, 145.0) | ||||

| T stage, n (%) | |||||

| T1 | 7860 | 3553 (45.2) | 2238 | 1413 (63.1) | <0.001 |

| T2 | 3613 (46.0) | 724 (32.4) | |||

| T3 | 644 (8.2) | 100 (4.5) | |||

| T4 | 50 (0.6) | 1 (0.04) | |||

| Gleason score, n (%) | |||||

| 2–5 | 7839 | 885 (11.3) | 2223 | 24 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| 6 | 4267 (54.4) | 1030 (46.3) | |||

| 7 | 2301 (29.4) | 1021 (45.9) | |||

| 8–10 | 386 (4.9) | 148 (6.7) | |||

| Positive cores %, mean ± SD, median (min, max) | 4475 | 40.2 ± 24.6 | 2218 | 42.8 ± 23.7 | <0.001 |

| 33.3 (0.0, 100.0) | 37.5 (0.0, 100.0) | ||||

| Positive cores ≥50%, n (%) | 4475 | 1686 (37.7) | 2218 | 961 (43.3) | <0.001 |

| Positive cores <34%, n (%) | 4475 | 2403 (53.7) | 2218 | 1079 (48.7) | <0.001 |

| Radiotherapy treatment year, median (min, max) | 7973 | 2003 (1994, 2010) | 2237 | 2010 (1998, 2015) | <0.001 |

| Radiotherapy treatment year, n (%) | |||||

| 1994–1999 | 7973 | 1953 (24.5) | 2237 | 1 (0.04) | – |

| 2000–2002 | 1973 (24.8) | 54 (2.4) | |||

| 2003–2005 | 2238 (28.1) | 181 (8.1) | |||

| 2006–2010 | 1809 (22.7) | 951 (42.5) | |||

| 2011–2015 | -- | 1050 (46.9) | |||

| Radiotherapy type, n (%) | |||||

| LDR–brachytherapy only | 7974 | 4508 (56.5) | 2266 | 1055 (46.6) | <0.001 |

| EBRT only | 2677 (33.6) | 967 (42.7) | |||

| HDR–brachytherapy + EBRT | 711 (8.9) | 168 (7.4) | |||

| LDR–brachytherapy + EBRT | 52 (0.7) | 76 (3.4) | |||

| HDR–brachytherapy only | 26 (0.3) | – | |||

| EBRT: Dose (Gy), mean ± SD, median (min, max) | 3439 | 63.3 ± 11.8 | 984 | 68.5 ± 12.6 | <0.001 |

| 66.0 (19.0, 79.8) | 73.5 (36.0, 80.0) | ||||

| EBRT: Dose per fraction (Gy), mean ± SD, median (min, max) | 2838 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 692 | 2.4 ± 1.0 | <0.001 |

| 2.0 (1.8, 3.0) | 2.0 (1.8, 7.4) | ||||

| EBRT: Biologic equivalent dose1 (Gy), mean ± SD, median (min, max) | 2838 | 137.5 ± 13.6 | 692 | 139.2 ± 24.2 | <0.001 |

| 136.0 (37.1, 165.0) | 150.0 (80.0, 173.9) | ||||

| ADT, n (%) | 7974 | 2999 (37.6) | 2266 | 310 (13.7) | <0.001 |

| ADT (months), mean ± SD, median (min, max) | 2660 | 10.5 ± 14.4 | 289 | 17.0 ± 12.7 | <0.001 |

| 6.0 (0.1, 143.7) | 18.0 (3.0, 36.0) | ||||

| Death, n (%) | 7974 | 1230 (15.4) | 2266 | 102 (4.5) | <0.001 |

| ASTRO II Phoenix biochemical failure, n (%) | 7550 | 1254 (16.6) | 2266 | 134 (5.9) | <0.001 |

| CAPRA score, mean ± SD, median (min, max) | 4394 | 3.1 ± 1.9 | 2212 | 3.3 ± 1.8 | <0.001 |

| 3 (0, 10) | 3 (1, 10) | ||||

| CAPRA-5, n (%) | |||||

| Low (0–2) | 4394 | 2050 (46.7) | 2212 | 881 (39.8) | <0.001 |

| Low-intermediate (3) | 1509 (34.3) | 850 (38.4) | |||

| High-intermediate (4–5) | 341 (7.8) | 194 (8.8) | |||

| High (6–7) | 369 (8.4) | 224 (10.1) | |||

| Very high (8–10) | 125 (2.8) | 63 (2.9) | |||

| CAPRA-3, n (%) | |||||

| Low (0–2) | 4394 | 2050 (46.7) | 2212 | 881 (39.8) | <0.001 |

| Intermediate (3–5) | 1850 (42.1) | 1044 (47.2) | |||

| High (6–10) | 494 (11.2) | 287 (13.0) | |||

| ProCaRS, n (%) | |||||

| Low | 7781 | 3928 (50.5) | 879 (39.6) | ||

| Low-intermediate | 2255 (29.0) | 926 (41.7) | |||

| High-intermediate | 501 (6.4) | 2220 | 157 (7.1) | <0.001 | |

| High | 759 (9.8) | 165 (7.4) | |||

| Very high | 338 (4.3) | 93 (4.2) | |||

| GUROC, n (%) | |||||

| Low | 7913 | 3928 (49.6) | 2257 | 879 (39.0) | <0.001 |

| Intermediate | 2883 (36.4) | 1120 (49.6) | |||

| High | 1102 (13.9) | 258 (11.4) | |||

| NCCN, n (%) | |||||

| Very low | 7913 | 877 (11.1) | 2257 | 291 (12.9) | <0.001 |

| Low | 2742 (34.7) | 556 (24.6) | |||

| Intermediate | 3191 (40.3) | 1151 (51.0) | |||

| High | 758 (9.6) | 245 (10.9) | |||

| Very high | 345 (4.4) | 14 (0.6) | |||

| Median followup (years)2, median (95% CI) | 7974 | 6.57 (6.42, 6.71) | 2266 | 3.67 (3.33, 4.00) | <0.001 |

Calculated using an α/βof 2;

reverse Kaplan-Meier Method; p values <0.05 are statistically significant.

ADT: androgen-deprivation therapy; CAPRA: Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment; CI: confidence interval; EBRT: external beam radiotherapy; GUROC: Genitourinary Radiation Oncologists of Canada; HDR: high-dose rate; LDR:low-dose rate; NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; ProCaRS: Prostate Cancer Risk Stratification; PSA: prostate-specific antigen; SD: standard deviation.

Comparison of different risk-stratification tools

The C-indices demonstrated a narrow range of improvement across the systems, with minimal clinically significant differences observed, particularly for the ProCaRS database (Table 2). This resulted in a maximum difference of 0.023 (range 0.700–0.723) for the ProCaRS database and 0.088 (range 0.568–0.656) for the CHUM database. However, C-index identified CAPRA score and ProCaRS as superior to the historical GUROC and NCCN risk-stratification systems for both databases. CAPRA-5 and CAPRA-3 were found to be superior to GUROC and NCCN for the CHUM database only. C-indices for CAPRA score, ProCaRS, GUROC, and NCCN were 0.723 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.701–0.745), 0.723 (95% CI 0.707, 0.739), 0.707 (95% CI 0.691–0.723), and 0.716 (95% CI 0.698–0.734) for the ProCaRS database and 0.656 (95% CI 0.599–0.713), 0.632 (95% CI 0.579–0.685), 0.568 (95% CI 0.517–0.619), and 0.600 (95% CI 0.547–0.653) for the CHUM database, respectively. DCA plots are shown in Fig. 1. Similarly, most of the risk-stratification systems demonstrated comparable net benefit to threshold probability profiles, with minimal clinically significant differences. For both databases, the CAPRA systems showed either equivalent or modest improvements in net benefit overall (as shown in grey).

Table 2.

Summary of concordance indices reported from Cox proportional hazards regression using 10-fold cross validation for biochemical failure-free survival for risk stratification variables separately by database

| Variable | ProCaRS database (n=7974) | CHUM database (n=2266) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| C-Index | 95% CI | C-Index | 95% CI | |

| CAPRA | 0.723 | (0.701, 0.745) | 0.656 | (0.599, 0.713) |

| CAPRA-5 | 0.713 | (0.691, 0.735) | 0.636 | (0.583, 0.689) |

| CAPRA-3 | 0.700 | (0.678, 0.722) | 0.635 | (0.584, 0.686) |

| ProCaRS | 0.723 | (0.707, 0.739) | 0.632 | (0.579, 0.685) |

| GUROC | 0.707 | (0.691, 0.723) | 0.568 | (0.517, 0.619) |

| NCCN | 0.716 | (0.698, 0.734) | 0.600 | (0.547, 0.653) |

CAPRA: Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment; CI: confidence interval; C-Index: concordance index; ProCaRS: Prostate Cancer Risk Stratification; GUROC: Genitourinary Radiation Oncologists of Canada; NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Fig. 1.

Decision curve analysis plots measured at five years following radiotherapy for (A) biochemical-failure-free survival (binary); (B) overall survival (binary); (C) biochemical failure-free survival (time-to-event); and (D) overall survival (time-to-event), comparing CAPRA Score, CAPRA-5, CAPRA-3, ProCaRS, and GUROC to the “treat all” condition for the CHUM database (n=2266). CAPRA: Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment; GUROC: Genitourinary Radiation Oncologists of Canada; NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; ProCaRS: Prostate Cancer Risk Stratification.

Additionally, each of the examined risk-stratification systems was found to be an overall significant predictor of BFFS for both databases (all p<0.001). For example, the CAPRA score (per one unit increase) was associated with a hazard ratio (HR) for BFFS of 1.39 (p<0.001) and 1.24 (p<0.001) for the ProCaRS and CHUM databases, respectively. Comparing CAPRA-3 intermediate- and high-risk to low-risk resulted in HRs of 3.27 (p<0.001) and 7.60 (p<0.001) for the ProCaRS database and 2.07 (p=0.001) and 3.74 (p<0.001) for the CHUM database, respectively. Compared to ProCaRS low-risk, this resulted in HRs of 2.22 (p<0.001), 5.61 (p<0.001), 5.95 (p< 0.001), and 10.87 (p<0.001) for the ProCaRS database for each respective ProCaRS risk category vs. HRs of 2.13 (p<0.001), 2.83 (p<0.001), 1.90 (p=0.050), and 3.77 (p<0.001) for the CHUM database.

Validation of the ProCaRS nomograms

The calibration plots of the ProCaRS nomograms predictive of five-year BFFS for LDR-brachytherapy and EBRT are shown in Fig. 2 (nomograms reproduced in Supplementary Fig. 1 with permission; available at www.cuaj.ca). External validation of the ProCaRS nomograms yielded favourable calibrations of R2=0.778 (LDR-brachytherapy) and R2=0.868 (EBRT). Given the consistent underestimation of survival for both nomograms, more validation is required to further calibrate the nomograms.

Fig. 2.

ProCaRS nomogram calibration plots predicting five-year ASTRO II Phoenix biochemical failure-free survival for (A) LDR-brachytherapy only; and (B) EBRT only (with and without linear probability adjustment) for the CHUM database (n=2266). BFFS: biochemical failure-free survival; EBRT: external beam radiotherapy; LDR: low-dose rate; ProCaRS: Prostate Cancer Risk Stratification.

Discussion

The importance of key clinical factors as prognostic tools is well known and has formed the basis of several commonly used prostate cancer risk-stratification models. As such, this study sought to compare predictive models that have been available for several years with recently developed tools in a combined cohort of over 10 000 patients treated with primary radiotherapy or brachytherapy.

First, we compared the different clinical predictive tools in the ProCaRS and CHUM databases. We found that the CAPRA score and ProCaRS were superior to the GUROC and NCCN risk-assessment models for predicting BFFS in both cohorts. However, many of these comparisons did not yield a clinically meaningful difference, with maximum concordance index differences of 0.023 and 0.088 for the ProCaRS and CHUM databases, respectively. This finding was also consistent with the degree of similarity observed between the various systems using DCA. As such, it is reasonable to conclude that all of the models tested differ little in their ability to stratify patients with prostate cancer. Thus, in order to warrant a more complex and possibly more time-consuming risk-stratification tool, a clinically meaningful improvement in predictability must be demonstrated. Given our results, it is probably more important to use a system that is user-friendly and easy to calculate in clinical practice.

Although our results demonstrate that clinical scoring systems perform reasonably well in predicting BFFS, further improvement in risk-stratification is possible. In order to increase our ability to discriminate patients and ultimately better tailor our treatments, we will likely need to complement clinical information with other potential prognostic factors, such as genomic biomarkers and/or radiological information. Currently, there exist several commercially available genomic biomarker tests for prostate cancer that are performed on biopsy or radical prostatectomy specimens.20–22 These are presently being validated in retrospective cohorts using various endpoints. Analogous to tests such as the Oncotype DX® Breast Cancer Assay,23 which can help define the benefit of chemotherapy and has been integrated into clinical practice, these new prostate cancer assays may help answer pertinent clinical questions. For instance, these tools might aid clinicians to decide between active surveillance and immediate treatment, adjuvant radiotherapy vs. observation, and radiation with or without hormones or hormones alone as salvage therapy upon PSA rise.24 The combination of a clinical score (CAPRA-S) with a genomic assay25 to predict for metastasis after prostatectomy26 have been recently studied. In the study by Cooperberg et al, patients with elevated scores on both CAPRA-S and a genomic assay were at very high risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality and should be considered for more aggressive therapies.25 However, the genomic assay was found to re-classify a significant number of patients classified as high-risk to intermediate-risk using CAPRA-S. Many of these patients subsequently experienced a biochemical failure. Finally, genomic markers might also be used in prospective clinical trials as inclusion/exclusion factors that enhance comparative cohorts for the desired endpoints. Future investigations will explore the development of hybrid risk-assessment tools to integrate existing prognostic factors currently in use with novel genomic markers.

This study also validated the ProCaRS five-year BFFS nomograms for LDR-brachytherapy and EBRT in an independent cohort. However, both nomograms consistently produced an underestimation of the true five-year BFFS values. This finding may be partially attributed to the limited number of patients with observed BFFS <90%, but is more likely due to the observed shorter followup in the CHUM database (p<0.001) in combination with the detection of fewer biochemical failures. Thus, it is possible that with additional followup and detection of previously unidentified biochemical failures, more favourable results would be observed. Further validation and adjustment of the nomograms may be required to account for variation in length of followup in future studies.

We believe these nomograms are clinically useful tools that can give clinicians prognostic information, which may be used in helping patients select the most appropriate treatment. For instance, the LDR-brachytherapy nomogram may help identify which patients will benefit most from exclusive LDR-brachytherapy. However, institution-specific adjustments may be needed, in part due to shorter followup in the CHUM database as compared to the ProCaRS database.

This study was limited by its retrospective nature and heterogeneity in data-collection between institutions. Given the range in treatment years for both databases, changes in data collection techniques may have occurred during this period. In addition to the type of radiotherapy offered (e.g. LDR-brachytherapy vs. EBRT), EBRT was offered under a range of conditions, including in combination with HDR-brachytherapy, conventional fractionation, and dose-escalation. Although some previous work had focused on these groups individually, the present study reports on the entire cohort to preserve maximum statistical power. Androgen-deprivation therapy was examined and incorporated into the development the ProCaRS nomograms,4 as validated in the current study, but was not adjusted for in the comparison of existing risk-stratification tools. As previously mentioned, the shorter followup of the CHUM database may have introduced a bias in the nomogram validation portion, but also precluded analysis of BFFS at later time points (e.g. >5 years) and other survival outcomes. Finally for concordance index comparisons, no consensus exists for what designates a clinically meaningful difference, although differences <0.10 are generally thought to be minimal (as was observed in the current study).

Conclusion

A direct comparison between existing risk-stratification tools, using a variety of statistical techniques, demonstrated minimal clinically significant differences in discriminative ability between the systems, favouring the CAPRA and ProCaRS systems. This study also externally validated two ProCaRS nomograms for BFFS that may help clinicians in treatment selection. The incorporation of novel prognostic variables, such as genomic markers, is needed in order to usher in a new era of risk-stratification for prostate cancer.

Supplementary Information

Footnotes

Supplementary data available at www.cuaj.ca

See related commentary on page 101.

Competing interests: Dr. Pickles has been a consultant for AbbVie, Astellas, and Janssen; and has received honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bayer, and Ferring. Dr. Morris has received speaker fees and travel expenses from Varian and is participating in clinical trials supported by Oncura and Sanofi. Dr. Crook has participated in clinical trials for the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group and for the British Columbia Cancer Agency. Dr. Catton has received payment from Abbott for developing content for patient information materials; and has received fellowship support from Abbott, AstraZeneca, and Paladin. Dr. Lukka has received grants and personal fees from AbbVie, Actavis, Amgen, Astellas, Astra Zeneca Bayer, Ferring, Janssen, and Sanofi, all outside of the submitted work. Dr. Taussky has received research support from Sanofi. The remaining authors report no competing personal or financial interests.

Research grants from the Ontario Institute of Cancer Research (High Impact Clinical Trials), the Canadian Association of Radiation Oncology (ACURA), Janssen, Inc. (unrestricted grant), and the Motorcycle Ride for Dad (London Chapter) supported this research project.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Rodrigues G, Warde P, Pickles T, et al. Pre-treatment risk stratification of prostate cancer patients: A critical review. Can Urol Assoc J. 2012;6:121. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.11085. https://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.11085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998;280:969–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.969. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.280.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohler JL, Armstrong AJ, Bahnson RR, et al. Prostate cancer, Version 1.2016. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:19–30. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warner A, Pickles T, Crook J, et al. Development of ProCaRS clinical nomograms for biochemical failure-free survival following either low-dose rate brachytherapy or conventionally fractionated external beam radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer. Cureus. 2015;7 doi: 10.7759/cureus.276. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lukka H, Warde P, Pickles T, et al. Controversies in prostate cancer radiotherapy: Consensus development. Can J Urol. 2001;8:1314–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell JA, Cooperberg MR, Elkin EP, et al. Ability of two pretreatment risk assessment methods to predict prostate cancer recurrence after radical prostatectomy: Data from CaPSURE. J Urol. 2005;173:1126–31. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000155535.25971.de. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000155535.25971.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kattan MW, Zelefsky MJ, Kupelian PA, et al. Pretreatment nomogram that predicts five-year probability of metastasis following three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4568–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.046. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kattan MW, Zelefsky MJ, Kupelian PA, et al. Pretreatment nomogram for predicting the outcome of three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy in prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3352–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.19.3352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zelefsky MJ, Kattan MW, Fearn P, et al. Pretreatment nomogram predicting 10-year biochemical outcome of three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy and intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Urology. 2007;70:283–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.03.060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2007.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delouya G, Krishnan V, Bahary J-P, et al. Analysis of the cancer of the prostate risk assessment to predict for biochemical failure after external beam radiotherapy or prostate seed brachytherapy. Urology. 2014;84:629–33. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.05.032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2014.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodrigues G, Lukka H, Warde P, et al. The prostate cancer risk stratification (ProCaRS) project: Recursive partitioning risk stratification analysis. Radiother Oncol. 2013;109:204–10. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.07.020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roach M, Hanks G, Thames H, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: Recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:965–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith GD, Pickles T, Crook J, et al. Brachytherapy improves biochemical failure-free survival in low-and intermediate-risk prostate cancer compared with conventionally fractionated external beam radiation therapy: A propensity score-matched analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91:505–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.11.018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson A, Keyes M, Pickles T, et al. Evaluating the Phoenix definition of biochemical failure after 125 I prostate brachytherapy: Can PSA kinetics distinguish PSA failures from PSA bounces? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:415–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooperberg MR, Pasta DJ, Elkin EP, et al. The University of California, San Francisco Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment score: A straightforward and reliable preoperative predictor of disease recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2005;173:1938–42. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000158155.33890.e7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000158155.33890.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooperberg MR, Broering JM, Carroll PR. Time trends and local variation in primary treatment of localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1117–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.0133. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.26.0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, D’Agostino RB, et al. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: From area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27:157. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vickers AJ, Elkin EB. Decision curve analysis: A novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Making. 2006;26:565–74. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06295361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X06295361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodrigues G, Lukka H, Warde P, et al. The prostate cancer risk stratification project: Database construction and risk stratification outcome analysis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:60–9. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuzick J, Berney D, Fisher G, et al. Prognostic value of a cell cycle progression signature for prostate cancer death in a conservatively managed needle biopsy cohort. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1095–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.39. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karnes RJ, Bergstralh EJ, Davicioni E, et al. Validation of a genomic classifier that predicts metastasis following radical prostatectomy in an at risk patient population. J Urol. 2013;190:2047–53. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.06.017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knezevic D, Goddard AD, Natraj N, et al. Analytical validation of the oncotype DX prostate cancer assay—a clinical RT-PCR assay optimized for prostate needle biopsies. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:690. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-690. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-14-690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, et al. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2817–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041588. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa041588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis JW. Novel commercially available genomic tests for prostate cancer: A roadmap to understanding their clinical impact. BJU Int. 2014;114:320–2. doi: 10.1111/bju.12695. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.12695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooperberg MR, Davicioni E, Crisan A, et al. Combined value of validated clinical and genomic risk stratification tools for predicting prostate cancer mortality in a high-risk prostatectomy cohort. Eur Urol. 2015;67:326–33. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.05.039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Den RB, Yousefi K, Trabulsi EJ, et al. Genomic classifier identifies men with adverse pathology after radical prostatectomy who benefit from adjuvant radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:944–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.0026. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.59.0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.