Abstract

Guided by Bronfenbrenner's ecological systems framework and informed by the rejection-identification model, this study examined the relationship between acculturation, discrimination, and ethnic–racial identity (ERI) searching and affirmation among a sample of Latino youths (N = 830; mean age = 12.2 years). Results revealed that higher levels of acculturation were associated with lower levels of searching and affirmation. Furthermore, higher perceived discrimination was associated with higher affirmation, but unrelated to searching. Finally, perceived discrimination significantly attenuated the negative associations between acculturation and adolescents’ ERI searching and affirmation. The article concludes with a discussion of practice implications.

Keywords: acculturation, discrimination, ethnic identity, Latino youths

Latino people represent over 16% of the U.S. population (Passel, Cohn, & Lopez, 2011), and 64% of them are of Mexican descent (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). By 2050, more than one-quarter of the U.S. population is projected to be Latino (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). This is a youthful subgroup, with Americans of Mexican origin being particularly young. The median age of Mexican Americans in the United States is 26 (Pew Research Center, 2016), compared with 37 for the general population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). Furthermore, Latino adolescents represent the fastest growing segment of the U.S. population (Ramirez, 2004), making research with this population particularly timely and important.

Adolescence is a critical period during which individuals undergo much psychosocial development. As with all adolescents, Latino youths experience the important and normative task of identity formation during adolescence (Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2012). However, as an ethnic minority population, Latino youths also encounter the additional task of developing an ethnic–racial identity (ERI) (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). ERI is a multidimensional construct that reflects the normative developmental task of exploring one's ethnic–racial background and gaining a sense of clarity regarding the meaning of this aspect of one's identity; ERI also involves the content of one's identity, such as the affect individuals feel toward their ethnic–racial background (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). The development of ERI is vital to adolescents’ psychosocial adjustment, including the development and maintenance of self-esteem (Cislo, 2008; Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen, & Guimond, 2009).

Researchers have explored a number of factors that predict ERI. One process posited to affect ERI is the ongoing process of acculturation, in which ethnic minority youths are also involved; acculturation may be defined as the shifting of values, belief systems, and behaviors that occurs from continuous contact between two cultures (Berry, 1997, 2003) and is thought to influence adolescents’ ERI development (Cavazos-Rehg & DeLucia-Waack, 2009; Cuéllar, Nyberg, Maldonado, & Roberts, 1997; Schwartz, Hernandez Jarvis, & Zamboanga, 2007). An additional influence on ERI that individuals become perceptive to during adolescence is ethnic discrimination; evidence suggests perceived discrimination is positively related to ERI (Branscombe, Schmitt, & Harvey, 1999; Cislo, 2008; Fisher, Wallace, & Fenton, 2000; Rosenbloom & Way, 2004). Guided by Bronfenbrenner's (1977, 1979) ecological systems theoretical framework and the rejection-identification model (Branscombe et al., 1999), this study examined the roles played by acculturation and discrimination in ERI development among a sample of Latino adolescents from a southwestern U.S. state.

Literature Review

Adolescence is an important time for ERI development (Phinney & Ong, 2007; Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2012). Broadly, ERI pertains to the extent to which one psychologically affiliates with his or her heritage culture and ethnic group (Phinney, 1992; Phinney, Horenczyk, Liebkind, & Vedder, 2001; Roberts et al., 1999). The construct has been conceptualized and operationalized for empirical study in a variety of ways (Phinney, 2003; Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2012). Perhaps most relevant to the study of adolescents is the Eriksonian conceptualization of identity development that emphasizes the importance of identity exploration (Erikson, 1968). Applied to ERI, scholars suggest that ERI involves multiple dimensions including (a) exploration or searching, and (b) affirmation or belonging (Phinney, 1992; Phinney & Ong, 2007; Umaña-Taylor Yazedjian, & Bámaca-Gómez, 2004). The current study focuses on these two dimensions of ERI (that is, searching and affirmation) because they are closely related to the process of cultural adaptation (reflected in our focus on acculturation) and evaluations of one's group (reflected in our focus on ethnic–racial discrimination). Ethnic searching, an action component, involves the pursuit of cultural experiences and information about one's ethnicity (Phinney & Ong, 2007). It can involve a variety of activities, such as attending cultural events or reading and talking to others about one's culture (Phinney & Ong, 2007). Although it is an ongoing process, ethnic exploration occurs most intensively during adolescence (Pahl & Way, 2006; Phinney, 2006). Ethnic affirmation is an affective aspect of ERI and is defined by the positive or negative feelings individuals’ ascribe to their ethnic background (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004). It is through searching of options and then affirmation of a set of core beliefs that adolescents develop a sense of ERI (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014).

Acculturation and ERI

Immigration yields ongoing cultural and psychological changes, a process known as acculturation (Berry, 1997, 2003). Acculturation occurs as a result of prolonged contact between two distinctive cultures and involves value, belief, attitudinal, and behavioral shifts in the individual (Berry, 1997, 2003). There are two main models of acculturation: (1) unidimensional and (2) bidimensional. According to the unidimensional model, acculturation is linear and similar to assimilation (Gordon, 1964). Acculturation exists on a scale of retention of heritage culture to adoption of receiving culture, with biculturalism falling somewhere in the middle of the continuum (Lawton & Gerdes, 2014). The bidimensional measurement of acculturation does not assume that an increase in orientation to the host culture results in a decrease in heritage culture orientation; new culture adoption and heritage culture maintenance are posited to be independent aspects of acculturation that exist on separate continuums (Berry, Phinney, Sam, & Vedder, 2006; Lawton & Gerdes, 2014).

Although inextricably linked, acculturation and ERI represent distinct aspects of an individual's broader cultural identity (Cuéllar et al., 1997; Schwartz et al., 2007). Because acculturation involves the adaptive integration of cultural influences and ERI involves gaining an understanding of and coming to a resolution regarding the role that one's ethnic–racial background will play in one's identity, it follows that acculturation may inform adolescents’ ERI development (Cavazos-Rehg & DeLucia-Waack, 2009). With a unidimensional approach, there is some empirical evidence that higher acculturation was associated with lower ERI among Mexican American college students (Cuéllar et al., 1997). Focusing just on Spanish proficiency among Mexican-origin adolescents, Phinney, Romero, Nava, and Huang (2001) found lower proficiency to be associated with lower ERI. The current study used a unidimensional measure of behavioral acculturation (that is, language) to assess the extent to which higher levels of mainstream Anglo orientation, relative to the heritage culture orientation, would be associated with ERI. Language has an integral effect on learning, culture, and socialization. The ability to speak English has an influence on an adolescent's ability to effectively communicate with, learn from, and develop values associated with the dominant culture. Previous studies have demonstrated that language is a comparable measure of acculturation to multidimensional measures (Marsiglia, Nagoshi, Parsai, & Castro, 2012). Also, there is currently a lack of valid and reliable developmentally appropriate measures that address the cognitive–behavioral domains of acculturation for youths and adolescents (Marsiglia, Kulis, Wagstaff, Elek, & Dran, 2005). Based on findings from prior work (that is, Cuéllar et al., 1997; Phinney, Horenczyk, et al., 2001), we hypothesized that higher acculturation would be associated with lower ERI searching and affirmation. Specifically, we expected that as adolescents feel relatively more engaged to the mainstream Anglo culture (that is, higher acculturation), they may be less motivated to engage in processes related to developing the aspect of their identity focused on their ethnic–racial heritage (for example, ERI search).

Discrimination and ERI

As with acculturation, discrimination is also posited as a predictor of ERI development (Branscombe et al., 1999; Rosenbloom & Way, 2004). Feagin and Eckberg (1980) described racial–ethnic discrimination as the product of actions and practices on the part of the dominant racial–ethnic group that differentially and negatively affect a minority racial–ethnic group. Perceived discrimination is salient among Latino youths who report experiencing differential treatment in their educational settings and among peers (Benner & Graham, 2011, 2013; Rosenbloom & Way, 2004). The rejection-identification model posits that discrimination is a manifestation of social rejection that activates individuals’ desire to belong and leads socially devalued outgroups (that is, ethnic minorities) to develop a heightened sense of ERI (Branscombe et al., 1999). In an active attempt to maintain a positive self-evaluation in the face of discrimination, ethnic minority members’ identification with the dominant in-group diminishes while their identification with the socially devalued outgroup increases (Branscombe et al., 1999).

The relationship between perceived discrimination and ERI has been empirically supported with a number of socially devalued groups (Branscombe et al., 1999; Garstka, Schmitt, Branscombe, & Hummert, 2004; Schmitt, Branscombe, Kobrynowicz, & Owen, 2002). Among Latino adolescents, research on the impact of discrimination on ERI formation is inconclusive and suggests a nuanced relationship. Cislo (2008) reported perceived discrimination to be positively associated with ERI, but noted ethnic group differences. Armenta and Hunt (2009) found discrimination to be differentially related to ERI depending on the type or level of discrimination assessed. Other researchers have reported no relationship (Pahl & Way, 2006) or a negative relationship between perceived discrimination and certain dimensions of ERI among Latino adolescents (Romero & Roberts, 2003). The inconclusive nature of findings may point toward the presence of important moderating variables (Fuller-Rowell, Ong, & Phinney, 2013). However, regardless of inconclusive results, ERI development is believed to be stimulated by processes that are typically considered racial in nature, including discrimination (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014).

The Current Study

Bronfenbrenner's (1977, 1979) ecological systems framework was used to orient the current study and contextualize the relevant constructs using a person-in-environment perspective. The framework posits that five nested environmental systems (micro-, meso-, exo-, macro-, and chronosystem) act on and influence adolescents and their development processes (Bronfenbrenner, 1994; Watling-Neal & Neal, 2013). Discriminatory experiences, acculturation processes, and ethnic identity development primarily involve the micro-, macro-, and chronosystem. The microsystem is the most immediate environment to individuals and comprises interactions between the individual and his or her surroundings. Experiences within the microsystem involving peer groups, family, and school impress upon individuals and influence their level of acculturation and ethnic identity; the microsystem is also the setting in which interpersonal discrimination occurs. The macrosystem represents cultural and social factors and patterns, such as customs and values. This broader system is also responsible for igniting acculturation processes and influencing ethnic identity development; furthermore, structural discrimination takes place within the macrosystem. The chronosystem involves transitions and changes in the individual over time, such as developmental shifts and migration. As experiences influenced by developmental stage and dependent on migration history, acculturation and ethnic identity are also shaped by the chronosystem (Bronfenbrenner, 1994; Watling-Neal & Neal, 2013).

In accordance with this orienting framework, we considered the way in which contextual factors in various systems act independently and interactively to inform adolescents’ ERI development. Specifically, we examined the impact of acculturation and discrimination on ERI searching and affirmation among young Latino adolescents in the southwestern United States. Furthermore, discrimination was examined as a moderator of the relationship between acculturation and ERI searching and affirmation. Based on prior literature, we hypothesized that acculturation would be negatively associated with ethnic–racial searching and affirmation (Cuéllar et al., 1997; Phinney, Horenczyk, et al., 2001). In line with the rejection-identification model (Branscombe et al., 1999), we hypothesized that perceived discrimination would be positively related to searching and affirmation (Cislo, 2008; Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2012). Finally, considering the prior literature on acculturation in the context of the rejection-identification model, we hypothesized that discrimination would interact with acculturation to inform searching and affirmation, such that the negative relationship between acculturation and the two ERI constructs would be attenuated at higher levels of perceived discrimination.

Method

Procedure

The data for this study came from a four-year-long randomized controlled trial (RCT) testing Families Preparing the New Generation, a parenting intervention developed to accompany Keepin’ it REAL, a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration–recognized classroom-based substance use prevention program for Mexican heritage youths (Marsiglia et al., 2012). All participants (parents and youths) were recruited at the school the youths attended. Eligible schools were those that had a large percentage (>70%) of Latino students and were located within the boundaries of the city of Phoenix. Nine schools agreed to participate in this study.

The eligible sample was drawn from two cohorts. Cohort 1 included youths who were in seventh grade during the 2009–2010 school year, and cohort 2 included youths who were in seventh grade during the 2010–2011 school year. Regardless of the cohort, the procedures remain the same. Trained study personnel initiated procedures to obtain informed parental consent at each school. Parents could choose one of three options: (1) to consent both parent and youth; (2) to consent only youth; or (3) to not consent either parent or youth. It should be noted that both parent and youth consent referred to data collection only, not administration of an intervention. The overall consent rate for the study was 77%, with a 76% consent rate for youths. In compliance with institutional review board requirements, consented youths had to first agree to participate through a written assent. In the fall (September to November) of the school year, a preintervention survey (wave 1) was administered. Only the results from wave 1 were used in this analysis. All surveys were available in English and Spanish and were translated following the procedures described in Rogler (1989); only 3% of youths completed the surveys in Spanish.

Sample

The youth participants (N = 846) self-identified as Hispanic or Latino, with 90% identifying as Mexican American. Demographic information related to the sample is presented in Table 1. Participants were on average 12.2 years old, with a fairly equal distribution between boys (48.8%) and girls (51.2%). The vast majority of respondents were born in the United States (78.9%) and lived in the country all of their lives (67.8%). The vast majority of participants were also second generation, with 64.3% reporting their mother was born in Mexico and 68.6% reporting their father was born in Mexico. A majority of respondents reported receiving As and Bs in school (40%), and the majority received free or reduced-price lunch (94.2%).

Table 1:

Sample Demographics (N = 846)

| Demographic Characteristic | f | % | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 12.20 (.49) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 425 | 51.20 | |

| Male | 405 | 48.80 | |

| Birthplace | |||

| United States | 656 | 78.85 | |

| Mexico | 167 | 20.07 | |

| Another country | 7 | 0.84 | |

| Mother's birthplace | |||

| United States | 234 | 28.57 | |

| Mexico | 527 | 64.35 | |

| Another country | 40 | 4.88 | |

| Father's birthplace | |||

| United States | 185 | 22.76 | |

| Mexico | 558 | 68.63 | |

| Another country | 39 | 4.80 | |

| Length of time in the United States | |||

| <1 year | 9 | 1.09 | |

| 1–5 years | 49 | 5.92 | |

| 6–10 years | 107 | 12.92 | |

| >10 years | 102 | 12.32 | |

| All of life | 561 | 67.75 | |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Free lunch | 705 | 85.98 | |

| Reduced-price lunch | 67 | 8.17 | |

| Neither | 48 | 5.85 | |

Measures

Acculturation

Acculturation was assessed through a measure of linguistic acculturation, given prior work demonstrating that linguistic acculturation is an adequate proxy for acculturation (Valencia & Johnson, 2008). Marin, Sabogal, Marin, Otero-Sabogal, and Perez-Stable's (1987) measure of linguistic acculturation (α = .74; current study α = .70) included three items (for example, “When talking with family members, what language do you usually speak?” “When you watch TV, listen to the radio, or listen to music, in what language do you usually listen?”); responses were scored on a five-point scale with response options of 1 = Spanish only, 2 = mostly Spanish, 3 = both languages, 4 = mostly English, and 5 = English only. Higher values represented a higher level of acculturation or more Anglo culture orientation.

Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure

ERI was measured using the revised six-item Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (Phinney & Ong, 2007) (α = .80), which assesses two dimensions of ERI, ethnic searching and affirmation. Ethnic searching was measured with three items, including “I have tried to learn more about my own ethnic group, such as its history and customs.” Ethnic affirmation was measured with three items, including “I am happy to be a part of my ethnic group.” Responses were scored on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly agree to 4 = strongly disagree. Responses were averaged for each subscale, and higher scores represented more searching or affirmation (that is, stronger ERI).

Perceived Discrimination

The Perceived Discrimination Scale was adapted from multiple scales. Three statements, (1) “People don't like me because of my ethnic group,” (2) “Kids at school say bad things or make jokes about me because of my ethnic group,” and (3) “People think my English is bad,” were taken from the Bicultural Stressors Scale (Romero & Roberts, 2003). One statement (“Kids my age exclude me from their activities or games because of my ethnic group”) was taken from the SAFE Acculturative Stress Scale (Mena, Padilla, & Maldonado, 1987). One statement (“Kids like me, who are from my ethnic group, can't get good grades at school) was taken from the Acculturative Hassles Scale (Vinokurov, Trickett, & Birman, 2002). The scale (α = .80) was developed due to the lack of valid and reliable measures to assess discrimination, particularly for Latino youths and adolescents. Responses ranged from 1 = strongly agree to 4 = strongly disagree. Responses were averaged, and higher scores indicated more perceived discrimination.

Analytic Plan

Multiple regression analysis was performed using SPSS (version 22) to assess whether acculturation and discrimination were significant predictors of ERI. The bivariate correlations, means, and standard deviations for the variables of interest are presented in Table 2. The analyses controlled for gender, age, length of time in the United States, birthplace, free or reduced-price lunch, and academic grades. A moderation analysis examined whether discrimination and acculturation interacted to significantly predict ERI searching and affirmation. Acculturation, perceived discrimination, and ERI searching and affirmation were centered prior to analysis. Following the guidelines set by Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken (2013), two conditions had to be satisfied for a moderation effect to be deemed to exist: (1) an interaction term with a statistically significant coefficient and (2) a significant increase in the amount of variance explained in ERI searching and affirmation.

Table 2:

Correlation Matrix, Means, and Standard Deviations of Variables of Interest

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Acculturation | — | 2.53 | 0.81 | |||

| 2. Discrimination | .06 | — | 1.48 | 0.54 | ||

| 3. Ethnic–racial identity exploration | –.15*** | .00 | — | 1.97 | 0.59 | |

| 4. Ethnic–racial identity commitment | –.12*** | .15*** | .49*** | — | 1.56 | 0.56 |

***p < .001.

Results

Direct Effects

Multiple regression analysis was used to test the direct effects of acculturation and discrimination on ERI affirmation (see Table 3) and searching (see Table 4). Results revealed a significant model [F(8, 713) = 3.398, p < .01] in which acculturation [t(713) = –3.920, p < .001], but not discrimination, was a significant predictor of ERI searching. As adolescents’ acculturation levels increased, searching behaviors decreased; acculturation explained 3.5% of the variance in ERI searching ( = .035). Results also showed a significant model [F(8, 713) = 7.279, p < .001] in which both acculturation [t(713) = –3.143, p < .01] and discrimination [t(713) = 4.259, p < .001] were significant predictors of ERI affirmation. As adolescents’ acculturation levels increased, their sense of affirmation decreased. However, as adolescents’ perceived discrimination increased, their ERI affirmation increased. Together, acculturation and discrimination explained 7.6% of the variance in ERI affirmation ( = .076).

Table 3:

Regression Analysis: Predicting Ethnic–Racial Identity Searching

| Predictor | b | β | r | 95% CI for p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acculturation | –.113*** | –.153*** | .035 | –.170 | –.057 |

| Discrimination | .010 | .009 | .016 | –.070 | –.091 |

| Acculturation × discrimination | .125** | .486** | .085 | .010 | –.183 |

Note: CI = confidence interval. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Table 4:

Regression Analysis: Predicting Ethnic–Racial Identity Affirmation

| Predictor | b | β | r | 95% CI for p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acculturation | –.088** | –.131** | .050 | –.139 | –.037 |

| Discrimination | .156*** | .155*** | .059 | .084 | .228 |

| Acculturation × discrimination | .125** | .436** | .049 | .044 | .001 |

Note: CI = confidence interval. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Interaction Effects

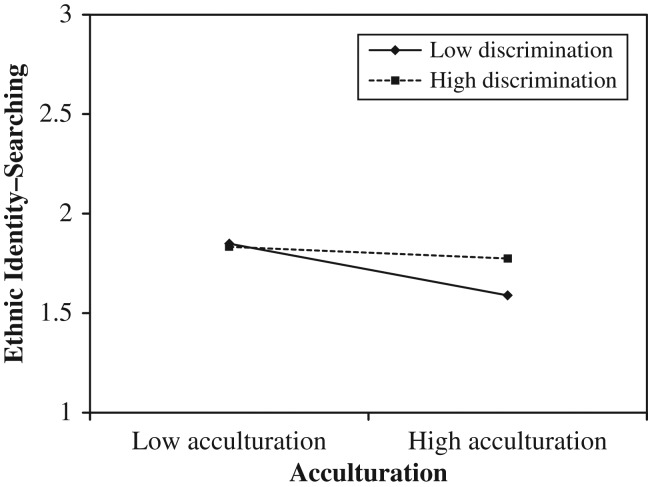

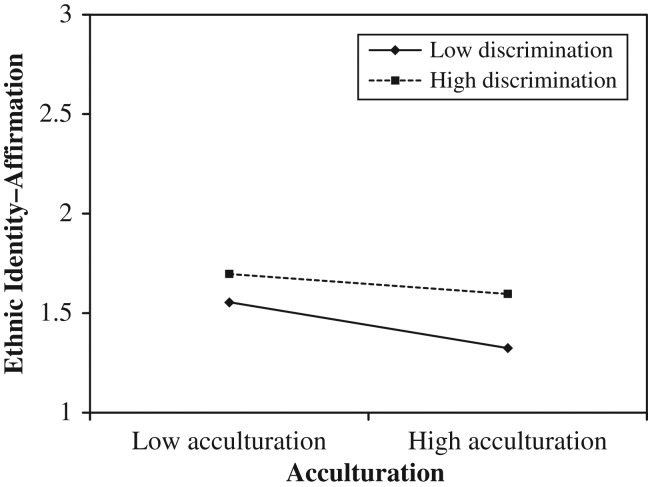

Results also showed a significant interaction between acculturation and discrimination in predicting both ERI searching and ERI affirmation. As hypothesized, discrimination moderated the relationship between acculturation and ERI searching [Δ = .01, ΔF(6, 715) = 7.675, p < .001, β = .125, t(715) = 2.770, p < .01] (see Figure 1), such that for those reporting high perceived discrimination, the negative association between acculturation and ERI searching was weaker, relative to those who reported low levels of perceived discrimination. Similarly, perceived discrimination moderated the relationship between acculturation and ERI affirmation [Δ = .012, ΔF(1, 712) = 9.321, p < .001, b = .153, t(712) = 3.053, p < .01] (see Figure 2), such that for those reporting high levels of discrimination, the negative association between acculturation and ERI affirmation was weaker, relative to those reporting low levels of discrimination.

Figure 1:

Discrimination as a Moderator of Acculturation and Ethnic–Racial Identity Searching

Figure 2:

Discrimination as a Moderator of Acculturation and Ethnic–Racial Identity Affirmation

Discussion

This study sought to further understand the relationship between acculturation, discrimination, and ERI. Acculturation is an important factor in identity development for Mexican-heritage youths in the United States; furthermore, like all minority youths, Mexican-heritage youths are at risk for experiencing discrimination (Benner & Graham, 2011, 2013; Pérez, Fortuna, & Alegría, 2008; Ramirez, 2004; Rosenbloom & Way, 2004). These culturally informed experiences may modify the normative developmental process of developing an ERI. Therefore, it is important to not only understand how acculturation can affect young people's sense of connection to their culture and, ultimately, the development of their identity (that is, ERI), but also understand how perceived discrimination may inform that association.

Results show that, as individual factors, acculturation and perceived discrimination were significant predictors of ERI affirmation for Mexican-heritage youths in hypothesized directions. Specifically, those who felt more connected to the dominant culture (that is, high acculturation) were less likely to explore their culture of origin (that is, lower searching) and less likely to feel positively about those traditions and values (that is, lower affirmation). Those who experienced more discrimination were more likely to affirm their culture of origin (that is, high levels of ethnic–racial affirmation), but were not more likely to participate in more searching for a connection to their traditional culture. As previously stated, the rejection-identification theory posits that youths seek a more in-depth connection with their culture of origin when experiencing discrimination. The results of this study are in line with this theory (that is, rejection-identification model) (Branscombe et al., 1999) because youths potentially sought a connection to their culture of origin to maintain a positive self-perception despite the negative emotions associated with discrimination. However, it appears that adolescents may only affirm the connection to their culture of origin, but may not be prompted to further explore it. Adolescents may feel that they have already learned as much as they possibly can about their culture of origin and may not feel the need to further explore it. Close familial ties (familisimo) (Ayón, Marsiglia, & Bermudez-Parsai, 2010) could also be a contributing factor to adolescents already possessing an extensive knowledge of their culture, despite a relationship with the dominant culture. However, this connection to the dominant culture may have lessened the connection to that culture. So perhaps adolescents feel that although they have the knowledge of their culture, they need a deeper relationship with it to combat the negative psychological and emotional effects of discrimination.

The results of the moderation analysis also provide insight into how discrimination and acculturation interact to affect ERI searching and affirmation. As expected, experiencing high levels of perceived discrimination attenuated the negative links between acculturation and ERI searching and affirmation. It is possible that, as youths who are more acculturated experience higher levels of discrimination, they may be thrust into ERI developmental processes and may do more searching and be motivated to feel more positive about their ethnic–racial group, particularly because they are attempting to understand why they are victims of ethnic–racial discrimination. As youths become highly acculturated, they perceive themselves to be fully a part of mainstream culture; thus, experiences with high levels of ethnic–racial discrimination are not consistent with youths’ perceptions of how they fit in with mainstream society. In contrast, youths who are not experiencing high levels of discrimination do not have to find a way to manage this dissonance (that is, high ethnic–racial discrimination in the context of perceiving oneself to be a member of mainstream society) and, therefore, may not be prompted to engage in ERI processes. It is important to note that these ideas are speculative and that future work is necessary to more comprehensively understand the direction of these effects and the mechanisms at play. Nevertheless, findings clearly indicate that the interface of perceived discrimination and acculturation is necessary to consider in attempts to understand how adolescents develop their ERI.

Although, in general, a large amount of the variance in ERI is not explained by discrimination and acculturation, the results are still significant. Although only 3.5% of ERI searching is explained by acculturation, its statistical significance means that it still plays a role in adolescents’ exploration of their culture of origin. Also, acculturation and discrimination only explain 5% and 5.9% of the variance, respectively, in ERI affirmation. Therefore, only a small portion of ERI can be explained through adolescent experiences of acculturation and discrimination. It is important to recognize how these factors that are an important part of Latino youths’ experiences affect their development. The results of this analysis also demonstrate that many other factors may be influencing ERI development; those factors need to be examined in future studies.

Implications for Practice

These findings have several implications for social work practice. The finding that those who are more Anglo-involved have lower ERI informs intervention planning; intervention efforts aimed at increasing ERI may be most effective when targeted at youths who are more acculturated. Furthermore, because perceived discrimination was found to buffer the loss of ERI that occurs with acculturation, interventions may have the greatest impact on Anglo-involved youths who perceive low discrimination. Helping youths enhance their connection to their culture of origin is important given the protective nature of ERI against antisocial behavior, maladjustment, and other negative outcomes (Cislo, 2008; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2009). In addition, the finding that perceived discrimination is positively related to ERI commitment reinforces the importance and value of using the strengths perspective when working with Latino youths. This study supports the resiliency of Latino youths in the face of discrimination; mental health practitioners and school counselors can help youths recognize that they know what they need in the face of adversity and affirm connection to culture as a coping mechanism and strength. Practitioners working with Latino youths can reinforce the development of ERI by encouraging youths to engage in cultural activities and take pride in their heritage and cultural background.

Limitations and Future Research

The current study offers important insights with respect to how two aspects of youths’ culturally informed experiences (that is, acculturation and discrimination) inform a third component of youths’ cultural orientation (that is, ERI); nevertheless, there are important limitations to consider, which provide direction for future research. First, although linguistic acculturation has been shown to be a valid proxy for acculturation (Valencia & Johnson, 2008), recent developments in the study of acculturation have led to the proliferation of a bidimensional model of acculturation in which culture of origin and dominant culture are assessed as separate subscales. However, as previously mentioned, scales need to be developed to properly assess the complexities of acculturation with youths and adolescents. Therefore, future research should include the development of those scales. Because linguistic acculturation is currently the most valid measure of acculturation, the results of this analysis have enormous implications for Latino adolescents and the development of their ERI. Once developmentally appropriate valid and reliable measures have been developed, it would be useful for future research to examine the relationship between acculturation, discrimination, and ERI using a bidimensional conceptualization of acculturation. Furthermore, future research should attempt to broaden the sample by including more youths who were not born in the United States, as the vast majority of this sample was born in the United States (79%). Comparison of those born in the United States with those born in Mexico can provide greater insight into how Mexican-heritage youths develop their identities and connect to their culture of origin. Although these data originated from a longitudinal study, wave 2 and wave 3 data collection points did not include measurements of discrimination and ERI. Therefore, the analysis was cross-sectional due to the limitations of the larger RCT. The cross-sectional nature of the current analysis does not enable conclusions to be drawn with respect to the direction of effects; however, the inability to establish a cause-and-effect relationship does not negate the importance of discovering significant relationships between acculturation, discrimination, and ERI development in adolescents. Future research should include a path analysis to understand the directional effects and potentially a mediating relationship between acculturation and discrimination.

Conclusion

Latino adolescents often struggle with acculturating to the dominant culture and maintaining their ERI. This study helps expand knowledge concerning ERI and what influences an adolescent's sense of self, particularly among Latino adolescents. For social workers in particular, this study provides insight into how Latino adolescents cope with external factors such as discrimination and acculturation, and how those factors may inform how adolescents develop their sense of ethnic identity and, in essence, who they are. This study also demonstrated that both acculturation and perceived discrimination inform youths’ ERI. Therefore, social workers working with Latino adolescents should consider how the dominant culture affects adolescents’ connection to protective influences such as ERI and the family. This study also contributes to the literature by providing a foundation for further understanding of the relationship between acculturation, discrimination, and ERI, and what factors influence ERI and could potentially strengthen that sense of ERI to provide a significant protective influence on Latino youths. A strong sense of ERI could potentially be a strong protective factor against maladaptive behaviors, such as substance use.

References

- Armenta B. E., & Hunt J. S. (2009). Responding to societal devaluation: Effects of perceived personal and group discrimination on the ethnic group identification and personal self-esteem of Latino/Latina adolescents. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 12(1), 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ayón C., Marsiglia F. F., & Bermudez‐Parsai M. (2010). Latino family mental health: Exploring the role of discrimination and familismo. Journal of Community Psychology, 38, 742–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner A. D., & Graham S. (2011). Latino adolescents’ experiences of discrimination across the first 2 years of high school: Correlates and influences on educational outcomes. Child Development, 82, 508–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner A. D., & Graham S. (2013). The antecedents and consequences of racial/ethnic discrimination during adolescence: Does the source of discrimination matter. Developmental Psychology, 49, 1602–1613. doi:10.1037/a0030557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 46, 5–68. [Google Scholar]

- Berry J. W. (2003). Conceptual approaches to acculturation In Chun K. M., Organista P. B., & Marin G. (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 17–37). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Berry J. W., Phinney J. S., Sam D. L., & Vedder P. (Eds.). (2006). Immigrant youth in cultural transition: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation across national contexts. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe N. R., Schmitt M. T., & Harvey R. D. (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32, 513–532. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. (1994). Ecological models of human development In Postlethwaite T. N. & Husen T. (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 568–587). Oxford, UK: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg P. A., & DeLucia-Waack J. L. (2009). Education, ethnic identity, and acculturation as predictors of self-esteem in Latino adolescents. Journal of Counseling and Development, 87, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cislo A. M. (2008). Ethnic identity and self-esteem. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 30(2), 230–250. doi:10.1177/0739986308315297 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J., Cohen P., West S. G., & Aiken L. S. (2013). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar I., Nyberg B., Maldonado R. E., & Roberts R. E. (1997). Ethnic identity and acculturation in a young adult Mexican-origin population. Journal of Community Psychology, 6, 535–549. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: W. W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin J. R., & Eckberg D. L. (1980). Discrimination: Motivation, action, effects, and context. Annual Review of Sociology, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher C. B., Wallace S. A., & Fenton R. E. (2000). Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29, 679–695. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Rowell T. E., Ong A. D., & Phinney J. S. (2013). National identity and perceived discrimination predict changes in ethnic identity commitment: Evidence from a longitudinal study of Latino college students. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 62, 406–426. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00486.x [Google Scholar]

- Garstka T. A., Schmitt M. T., Branscombe N. R., & Hummert M. L. (2004). How young and older adults differ in their responses to perceived age discrimination. Psychology and Aging, 19, 326–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M. M. (1964). Assimilation in American life: The role of race, religion, and national origins. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton K. E., & Gerdes A. C. (2014). Acculturation and Latino adolescent mental health: Integration of individual, environmental, and family influences. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 17, 385–398. doi:10.1007/s10567-014-0168-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G., Sabogal F., Marin B. V., Otero-Sabogal R., & Perez-Stable E. J. (1987). Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 9(2), 183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia F. F., Kulis S., Wagstaff D. A., Elek E., & Dran D. (2005). Acculturation status and substance use prevention with Mexican and Mexican-American youth. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 5(1–2), 85–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia F. F., Nagoshi J. L., Parsai M., & Castro F. G. (2012). The influence of linguistic acculturation and parental monitoring on the substance use of Mexican-heritage adolescents in predominantly Mexican enclaves of the Southwest US. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 11(3), 226–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mena F. J., Padilla A. M., & Maldonado M. (1987). Acculturative stress and specific coping strategies among immigrant and later generation college students. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 9(2), 207–225. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl K., & Way N. (2006). Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity among urban black and Latino adolescents. Child Development, 77, 1403–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passel J. S., Cohn D., & Lopez M. H. (2011, March 24). Hispanics account for more than half of nation's growth in past decade Retrieved from Pew Research Center, Hispanic Trends Web site: http://www.pewhispanic.org/2011/03/24/hispanics-account-for-more-than-half-of-nations-growth-in-past-decade/

- Pérez D. J., Fortuna L., & Alegría M. (2008). Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 421–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center (2016). The nation's Latino population is defined by its youth. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2016/04/20/the-nations-latino-population-is-defined-by-its-youth/

- Phinney J. S. (1992). The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7, 156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney J. S. (2003). Ethnic identity and acculturation In Chun K. M., Organista P. B., & Marin G. (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 63–81). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney J. S. (2006). Ethnic identity exploration in emerging adulthood In Arnett J. J. & J. L., Tanner (Eds.), Coming of age in the 21st century: The lives and contexts of emerging adults (pp. 117–134). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney J. S., Horenczyk G., Liebkind K., & Vedder P. (2001). Ethnic identity, immigration, and well-being: An interactional perspective. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 493–510. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney J. S., & Ong A. D. (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 271–281. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271 [Google Scholar]

- Phinney J. S., Romero I., Nava M., & Huang D. (2001). The role of language, parents, and peers in ethnic identity among adolescents in immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30, 135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez R. R. (2004). We the people: Hispanics in the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, Department of Commerce. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R. E., Phinney J. S., Masse L. C., Chen Y. R., Roberts C. R., & Romero A. (1999). The structure of ethnic identity in young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. Journal of Early Adolescence, 19, 301–322. [Google Scholar]

- Rogler L. H. (1989). The meaning of culturally sensitive research. American Journal of Psychiatry, 146, 296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero A. J., & Roberts R. E. (2003). The impact of multiple dimensions of ethnic identity on discrimination and adolescents’ self-esteem. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33, 2288–2305. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom S. R., & Way N. (2004). Experiences of discrimination among African American, Asian American, and Latino adolescents in an urban high school. Youth & Society, 35, 420–451. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt M. T., Branscombe N. R., Kobrynowicz D., & Owen S. (2002). Perceiving discrimination against one's gender group has different implications for well-being in women and men. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S. J., Hernandez Jarvis L., & Zamboanga B. L. (2007). Ethnic identity and acculturation in Hispanic early adolescents: Mediated relationships to academic grades, prosocial behaviors, and externalizing symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13, 364–373. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña‐Taylor A. J., Gonzales‐Backen M. A., & Guimond A. B. (2009). Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity: Is there a developmental progression and does growth in ethnic identity predict growth in self‐esteem. Child Development, 80, 391–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor A. J., & Guimond A. B. (2012). A longitudinal examination of parenting behaviors and perceived discrimination predicting Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 1, 14–35. doi:10.1037/2168-1678.1.S.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor A. J., Quintana S. M., Lee R. M., Cross W. E., Rivas‐Drake D., Schwartz S., et al. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development, 85, 21–39. doi:10.1111/cdev.12196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor A. J., Yazedjian A., & Bámaca-Gómez M. Y. (2004). Developing the Ethnic Identity Scale using Eriksonian and social identity perspectives. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 4, 9–38. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau (2009). Hispanic heritage month 2009: September 15–October 15. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/facts_for_features_special_editions/cb09-ff17.html

- U.S. Census Bureau (2011). Hispanic heritage month 2011: September 15–October 15. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/pdf/cb11ff-18_hispanic.pdf

- Valencia E. Y., & Johnson V. (2008). Acculturation among Latino youth and the risk for substance use: Issues of definition and measurement. Journal of Drug Issues, 38(1), 37–68. [Google Scholar]

- Vinokurov A., Trickett E. J., & Birman D. (2002). Acculturative hassles and immigrant adolescents: A life-domain assessment for Soviet Jewish refugees. Journal of Social Psychology, 142, 425–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watling-Neal J., & Neal Z. P. (2013). Nested or networked? Future directions for ecological systems theory. Social Development, 22, 722–737. [Google Scholar]