Abstract

Background and purpose

The use of a cemented cup together with an uncemented stem in total hip arthroplasty (THA) has become popular in Norway and Sweden during the last decade. The results of this prosthetic concept, reverse hybrid THA, have been sparsely described. The Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association (NARA) has already published 2 papers describing results of reverse hybrid THAs in different age groups. Based on data collected over 2 additional years, we wanted to perform in depth analyses of not only the reverse hybrid concept but also of the different cup/stem combinations used.

Patients and methods

From the NARA, we extracted data on reverse hybrid THAs from January 1, 2000 until December 31, 2013. 38,415 such hips were studied and compared with cemented THAs. The Kaplan-Meier method and Cox regression analyses were used to estimate the prosthesis survival and the relative risk of revision. The main endpoint was revision for any reason. We also performed specific analyses regarding the different reasons for revision and analyses regarding the cup/stem combinations used in more than 500 cases.

Results

We found a higher rate of revision for reverse hybrids than for cemented THAs, with an adjusted relative risk of revision (RR) of 1.4 (95% CI: 1.3–1.5). At 10 years, the survival rate was 94% (CI: 94–95) for cemented THAs and 92% (95% CI: 92–93) for reverse hybrids. The results for the reverse hybrid THAs were inferior to those for cemented THAs in patients aged 55 years or more (RR =1.1, CI: 1.0–1.3; p < 0.05). We found a higher rate of early revision due to periprosthetic femoral fracture for reverse hybrids than for cemented THAs in patients aged 55 years or more (RR =3.1, CI: 2.2–4.5; p < 0.001).

Interpretation

Reverse hybrid THAs had a slightly higher rate of revision than cemented THAs in patients aged 55 or more. The difference in survival was mainly caused by a higher incidence of early revision due to periprosthetic femoral fracture in the reversed hybrid THAs.

The reverse hybrid THA is the combination of a cemented all-polyethylene cup and an uncemented stem. It has become popular in Norway and Sweden (Lindalen et al. 2011). Based on the findings from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR) in the 1990s with poorer results with uncemented cups than with cemented cups, and good long-term results for some uncemented stems in young patients, Havelin et al. (2000) suggested performing randomized trials to evaluate the efficacy of cemented cups combined with uncemented stems in young patients.

McNally et al. (2000) reported more than 90% survival with a cemented cup/uncemented stem combination after 12 years. The reverse hybrid concept also found support in some Nordic registery studies, which demonstrated that in young patients some uncemented femoral stems could outperform some cemented stems, and that cemented cups could outperform uncemented metal-backed cups with UHMWPE that was not crosslinked (Havelin et al. 2002, Hallan et al. 2007, Hailer et al. 2010, Mäkelä et al. 2010).

In 2011, the NAR published results of 3,963 reverse hybrid THAs and found no improvement in implant survival compared to cemented THA at 5 and 7 years, regardless of age (Lindalen et al. 2011). The Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association (NARA) (Mäkelä et al. 2014) showed better results for cemented THAs than for reverse hybrid THAs in patients who were 65 years or older. In a study on patients younger than 55 years from the same collaboration, a tendency was found of a lower revision rate for any reason with reverse hybrid THAs than with cemented THAs (Pedersen et al. 2014).

In the present study, we compared the results of reverse hybrid THAs with those of cemented THAs based on larger numbers and a longer follow-up than previously published. We also wanted to perform detailed analyses regarding cup/stem combinations of reverse hybrid THAs and to compare highly crosslinked and non- or low-crosslinked cups.

Patients and methods

The NARA was established in 2007 (Havelin 2011). It is a collaboration of the national arthroplasty registries of Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden. Individual data on primary and revision THAs are collected in each country. A common THA dataset with anonymous data has been established. 496,567 primary THAs were registered in the 4 national registries between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2013. All primary cemented and reverse hybrid THAs operated during the period 2000–2013 were included, regardless of the reason for hip replacement. Surface replacements and THAs with unknown or missing information on fixation were excluded.

The diagnoses Calve-Legg-Perthes, slipped femoral capital epiphyses, and dysplasia were merged into 1 group named childhood hip disease. Patients with bilateral procedures were included, as earlier research has shown that this does not bias the results (Lie et al. 2004, Ranstam and Robertsson 2010).We found 38,415 reverse hybrid THAs and 267,755 cemented THAs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data for cemented and reverse hybrid THAs. Comparison of survival (in %) and relative risk (RR) of revision, with all revisions as endpoint for the total material

| Cemented | Reverse hybrid | |

|---|---|---|

| n = 267,755 | n = 38,415 | |

| Revisions | 9,975 | 1,426 |

| Median follow-up (IQR) | 6.2 (3.2–9.3) | 3.3 (1.6–5.9) |

| Median age (IQR) | 73 (67–79) | 64 (57–72) |

| % Men | 35 | 40 |

| Deceased | 65,379 | 2,242 |

| Diagnosis, % | ||

| Osteoarthritis | 81.0 | 79.0 |

| RA/inflammatory | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Sequelae hip fracture | 11.2 | 8.0 |

| Childhood disease | 1.7 | 6.4 |

| Femoral head necrosis | 2.2 | 2.4 |

| Others | 1.3 | 1.5 |

| 5-year survival, % | 97 (97–97) | 96 (96–96) |

| number at risk | 55,864 | 11,717 |

| 10-year survival, % | 95 (94–95) | 92 (92–93) |

| number at risk | 52,477 | 2,045 |

| RRa (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) |

Adjusted for age, sex, period, and diagnosis

IQR: interquartile range.

In this study, we decided to use cemented THAs as comparator since this combination had the lowest overall revision rate for all age groups in the previous studies (Mäkelä et al. 2014; Pedersen et al. 2014).

We analyzed the results for the 2 modes of fixation in general and in 4 age groups (< 55, 55–64, 65–74, and >74 years) and we studied the assessed relative risks of revision caused by fracture, infection, loosening, and dislocation. We also performed separate analyses of males and females regarding periprosthetic fractures. Furthermore, we studied the influence of death as a possible competing risk for revision.

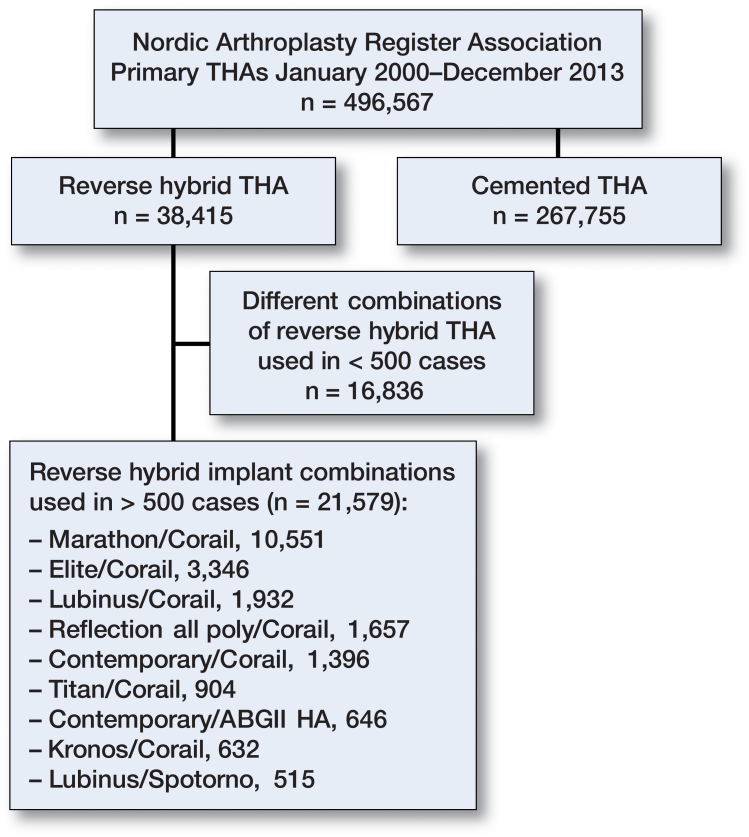

35 stem and cup combinations had each been used in more than 100 cases. 9 combinations had been used in more than 500 cases. These 9 combinations were studied more closely with Cox analyses for 3 different follow-up periods (0–1, 1–5, and >5 years) with adjustments for age, sex, and diagnosis. Cemented THAs were used as a reference (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study.

Highly crosslinked all-polyethylene cups were introduced onto the Nordic market during the study period. The influence of this potential confounder was studied in separate analyses. Lastly, we looked at the influence of head size and bearing materials on the overall results.

Statistics

The endpoint in the analyses was implant revision, meaning the exchange or removal of either the whole THA or any part of it. To estimate the survival of the THAs, we used the Kaplan-Meier method with 95% confidence interval (CI). We stopped calculating survival probabilities when less than 20 hips remained at risk. The follow-up time was calculated from primary operation until implant revision or the patient was censored at the end of the study (December 31, 2013), at death, or emigration. To calculate median follow-up time, we used the reverse Kaplan-Meier method. The relative risk of revision (RR) were estimated (with 95% CI) by using Cox regression analyses with adjustments for age (< 55, 55–64, 65–74, and >74 years), sex, diagnosis, and time period. We considered p-values of less than 0.05 to be statistically significant. To investigate death as a possible competing risk for revision, we performed a competing-risk analysis (Fine and Gray 1999). For statistical analysis, we used SPSS version 22.0 and the R statistical software package version 3.2.1.

Results

The median length of follow-up was 6 years for the cemented THAs and 3 years for the reverse hybrid THAs. Mean age at the time of surgery for the reverse hybrid THAs was 64 years, as compared to 73 years for cemented THAs (Table 1). There was a higher proportion of males in the reverse hybrid group (40%) than in the cemented group (35%) (Table 1). The implant survival of the cemented THAs was 97% (CI: 97–97) at 5 years, as opposed to 96% (CI: 96–96) for reverse hybrid THAs, using any reason for revision as endpoint. At 10 years, implant survival was 95% (CI: 94–95) for cemented THAs and 92% (CI: 92–93) for reverse hybrid THAs (Table 1).

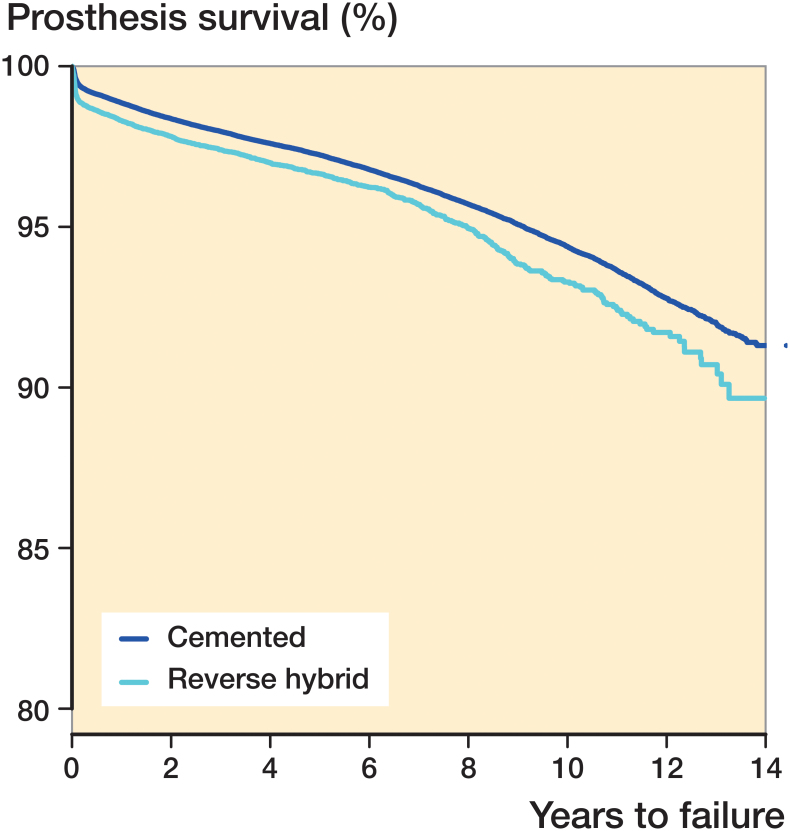

After adjustment for sex, age, diagnosis, and time period, reverse hybrid THAs had a relative risk of revision of 1.4 (CI: 1.3–1.5; p < 0.001) (Figure 2) compared to cemented THAs. When stratifying for time period and age groups, the results did not change when accounting for death as a competing risk.

Figure 2.

Cox survival analysis with adjustment for age, sex, time period, and diagnosis, and with any revision of the implant as endpoint. RR =1.4 (CI: 1.3–1.5; p < 0.001).

Aseptic loosening, deep infection, and dislocation were the 3 most frequent causes of revision for both reverse hybrid THA and cemented THA (36% vs. 41%, 22% vs. 20%, 15% vs. 26%, respectively, expressed as percentage of all causes of revision with each concept).

The relative risk of revision for loosening was higher in reverse hybrids in patients aged ≥65 years (RR =1.6, CI: 1.4–2.0; p < 0.001). We were not able to analyze separate results for loosening of the cups and stems, since the data from the NARA do not differentiate between revisions of different parts of the prosthesis.

There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of revision for infection in the younger patient groups. For patients older than 74 years with a reverse hybrid THA, there was a 1.7 times (CI: 1.3–2.1; p < 0.001) higher risk of revision due to infection. We found no significant difference in the risk of revision due to dislocation.

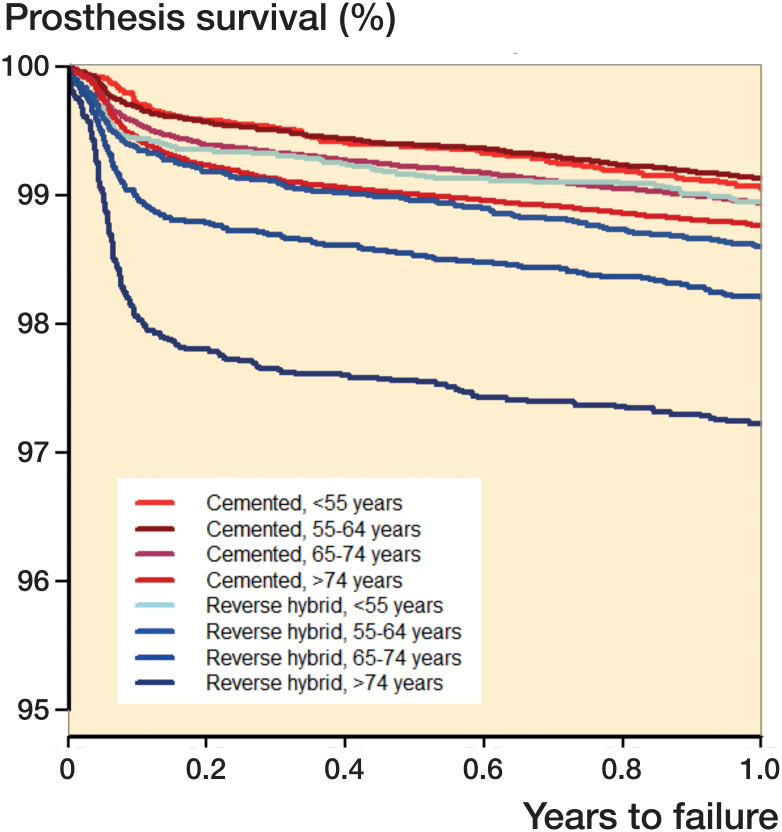

During the first year after the index operation, the risk of revision in patients younger than 55 years was similar between reverse hybrid and cemented THAs. From the age of 55 years, those with reverse hybrid THA had a higher risk of early revision than those in the corresponding age group with cemented THAs (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Revisions in the first 12 months after surgery. Cox survival analysis with adjustment for sex, diagnosis, and period.

Reverse hybrid THAs were associated with an elevated risk of revision due to periprosthetic fracture in all age groups except those less than 55 years old. The relative risk increased with age from 3 in patients 55–64 years of age to 6 in patients aged >74 years (Table 2). The highest increase was observed in women over 74 years old when compared to cemented implants in the corresponding age group (RR =8, CI: 5–12; p < 0.001) (Table 3). Of all the fractures reported (n = 878), two-thirds were reported within the first year after surgery.

Table 2.

Comparison of reverse hybrid THAs and cemented THAs in corresponding age groups regarding risk of revision. Cemented THAs were defined as 1 when calculating RR. Cox analysis was used, with adjustment for gender, primary diagnosis, and period

| Age group | RRa | CI (95%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 55 years | |||

| All revisions | 0.9 | 0.8–1.0 | 0.07 |

| Fracture | 1.4 | 0.8–2.5 | 0.3 |

| Infection | 0.7 | 0.5–1.1 | 0.08 |

| Loosening | 0.9 | 0.7–1.1 | 0.2 |

| Dislocation | 0.8 | 0.5–1.1 | 0.2 |

| 55–64 years | |||

| All revisions | 1.1 | 1.0–1.3 | 0.013 |

| Fracture | 3.1 | 2.2–4.5 | <0.001 |

| Infection | 1.1 | 0.8–1.4 | 0.7 |

| Loosening | 1.1 | 0.9–1.3 | 0.5 |

| Dislocation | 0.8 | 0.6–1.0 | 0.1 |

| 65–74 years | |||

| All revisions | 1.5 | 1.3–1.7 | <0.001 |

| Fracture | 4.0 | 2.9–5.3 | <0.001 |

| Infection | 1.1 | 0.9–1.3 | 0.6 |

| Loosening | 1.6 | 1.4–2.0 | <0.001 |

| Dislocation | 0.8 | 0.6–1.0 | 0.08 |

| > 74 years | |||

| All revisions | 2.0 | 1.8–2.3 | <0.001 |

| Fracture | 5.8 | 4.3–7.9 | <0.001 |

| Infection | 1.7 | 1.3–2.1 | <0.001 |

| Loosening | 2.6 | 2.0–3.5 | <0.001 |

| Dislocation | 1.2 | 0.9–1.6 | 0.2 |

Cemented THA same age group =1

Table 3.

Relative risk of revision due to fracture in men and women

| Men |

Women |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRa | 95% CI | p-value | RRa | 95% CI | p-value | |

| < 55 | 1.4 | 0.5–3.4 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 0.6–3.0 | 0.4 |

| 55–64 | 2.1 | 1.2–3.5 | 0.006 | 4.9 | 2.9–8.3 | < 0.001 |

| 65–74 | 2.1 | 1.3–3.4 | 0.004 | 6.7 | 4.5–9.9 | < 0.001 |

| > 74 | 3.5 | 2.0–6.0 | < 0.001 | 7.9 | 5.4–11.5 | < 0.001 |

Cemented THA same age group =1, with adjustment for diagnosis and period.

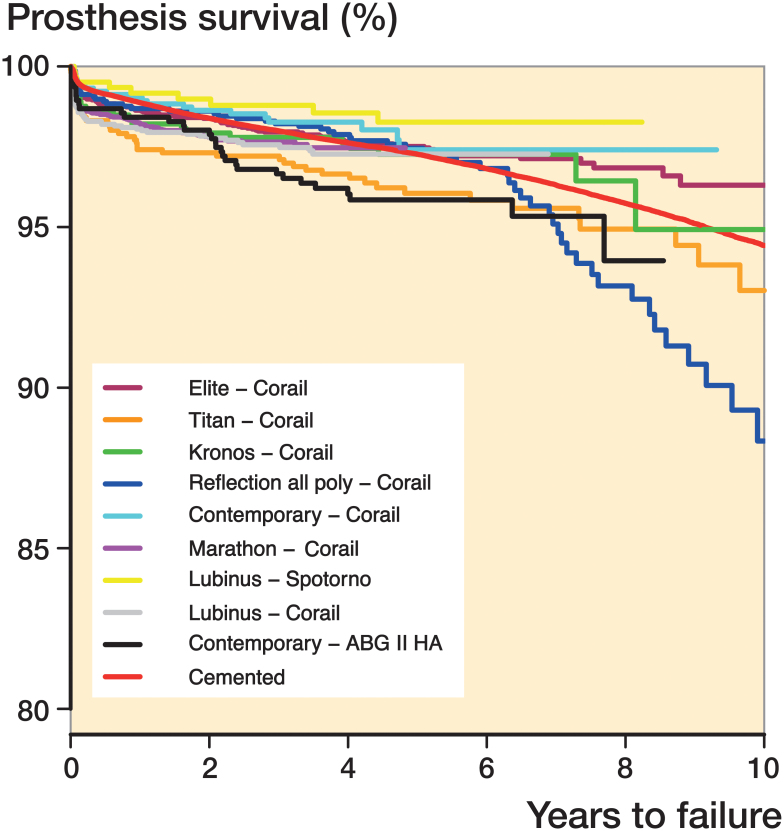

9 different cup/stem combinations in reverse hybrids were studied in detail (those that had each been used in more than 500 cases) (Figure 4 and Table 4). We found no significant difference in survival for 7 out of the 9 different combinations studied compared to cemented THAs. The combination Marathon cup/Corail stem, which also had the shortest follow-up, showed an increased risk of revision when compared to the entire group of cemented implants (RR =1.3, CI: 1.2–1.5; p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Prosthesis survival with revision of either cup or stem for any reason, and with adjustment for sex, age, diagnosis, and period.

Table 4.

Cox regression results for reverse hybrid brand combinations compared to cemented THAs, with adjustment for age, sex, period, and diagnosis. The endpoint was any revision. Median follow-up was calculated by "reverse Kaplan-Meier"

| Prosthesis cup/stem | Total n | Revised n | RR | 95% CI | p-value | Median follow-up (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cemented THA | 267,755 | 9,975 | 1 | 6.2 (3.2–9.3) | ||

| Elite/Corail | 3,346 | 107 | 0.8 | 0.7–1.0 | 0.05 | 5.3 (3.5–6.8) |

| Titan/Corail | 904 | 45 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.7 | 0.2 | 5.6 (4.1–8.6) |

| Kronos/Corail | 632 | 22 | 0.9 | 0.6–1.3 | 0.5 | 5.5 (4.3–6.9) |

| Reflection all-poly/Corail | 1,183 | 60 | 1.3 | 1.0–1.7 | 0.05 | 5.2 (4.1–7.2) |

| Contemporary/Corail | 902 | 20 | 0.7 | 0.5–1.1 | 0.1 | 4.0 (2.9–5.2) |

| Marathon/Corail | 8,856 | 202 | 1.3 | 1.2–1.5 | < 0.001 | 1.6 (0.8–2.6) |

| Lubinus/Spotorno | 515 | 10 | 0.6 | 0.3–1.0 | 0.06 | 5.1 (3.1–6.3) |

| Lubinus/Corail | 1,932 | 54 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.5 | 0.3 | 3.1 (1.8–4.3) |

| Contemporary/ABG II HA | 646 | 32 | 1.4 | 1.0–1.9 | 0.08 | 5.0 (3.9–6.8) |

IQR: interquartile range.

Studies of different time periods showed that 6 reverse hybrid implant combinations had a higher risk of revision than cemented THAs in the first period (0–1 year of follow-up) (Table 5). In the third period (> 5 years of follow-up), which included 6 combinations, the Elite/Corail combination had a lower risk of revision than cemented THAs (RR =0.4, CI: 0.2–0.7; p = 0.02) whereas Reflection all-poly/Corail had a higher risk of revision (RR =2.0, CI: 1.4–3.1; p < 0.001) (Table 6).

Table 5.

Cox regression results for reverse hybrid brand combinations compared to cemented THAs concerning early revision (< 1 year), with adjustment for age, sex, period, and diagnosis

| Prosthesis cup/stem | Total n | Revised n | RR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cemented THA | 267,755 | 3,038 | 1 | ||

| Elite/Corail | 3,346 | 56 | 1.5 | 1.2–2.0 | 0.002 |

| Titan/Corail | 904 | 26 | 2.8 | 1.9–4.1 | < 0.001 |

| Kronos/Corail | 632 | 13 | 1.8 | 1.0–3.1 | 0.04 |

| Reflection all-poly/Corail | 1,183 | 18 | 1.4 | 0.9–2.3 | 0.1 |

| Contemporary/Corail | 902 | 10 | 0.9 | 0.5–1.7 | 0.8 |

| Marathon/Corail | 8,856 | 172 | 1.8 | 1.5–2.1 | < 0.001 |

| Lubinus/Spotorno | 515 | 5 | 0.9 | 0.4–2.3 | 0.9 |

| Lubinus/Corail | 1,932 | 43 | 1.8 | 1.4–2.5 | < 0.001 |

| Contemporary/ABG II HA | 646 | 12 | 2.0 | 1.1–3.5 | 0.01 |

Table 6.

Cox regression results for reverse hybrid brand combinations compared to cemented THAs with follow-up of more than 5 years, and with adjustment for age, sex, and diagnosis

| Prosthesis cup/stem | Total n | Revised n | RR | 95% CI | p-value | At 8 years n | At 10 years n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cemented THA | 155,845 | 2,825 | 1 | 90,886 | 52,447 | ||

| Elite/Corail | 1,818 | 11 | 0.4 | 0.2–0.7 | 0.02 | 426 | 168 |

| Titan/Corail | 499 | 7 | 0.6 | 0.3–1.3 | 0.2 | 239 | 107 |

| Kronos/Corail | 369 | 2 | 0.3 | 0.1–1.4 | 0.1 | 74 | 30 |

| Reflection all-poly/Corail | 628 | 25 | 2.0 | 1.4–3.1 | < 0.001 | 217 | 88 |

| Contemporary/ABG II HA | 311 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.1–1.8 | 0.3 | 51 | – |

Different head sizes and different bearing materials did not affect the results significantly.

Because of low numbers during the first years of the study period, we were only able to compare the results for the highly crosslinked and the non- or low-crosslinked all-poly cups from 2004–2013. We found similar survival for the 2 different cups.

Discussion

We found that reverse hybrid THA had a slightly higher rate of revision than all-cemented THAs at 10-year follow-up. The main reason was a higher number of early revisions, especially due to periprosthetic femoral fractures in reverse hybrid THAs used in elderly patients.

Reverse hybrid THA has been used on a regular basis since the year 2000 in Norway, and reached a proportion of one-third of all primary THAs implanted in the year 2011 (Norwegian Arthroplasty Register Annual Report 2012). The proportion in Sweden was 13% for the same year (Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register Annual Report 2012). In Finland and Denmark, reverse hybrid is an uncommonly used concept, with only 861 in Denmark and 3,022 in Finland during the study period.

McNally et al. (2000) published very good results for the Furlong stem together with a cemented ultra-high-density polyethylene cup at 10–11 years, with 99% survival for the stem and 95% for the cup. Lindalen et al. (2011) found equal survival of reverse hybrid THAs and cemented THAs at 5 years and 7 years (cemented: 97.0% and 96.0%, respectively; reverse hybrid: 96.7% and 95.7%) whereas we found higher survival rates with use of all-cemented THAs at 5 and 10 years. This difference can be explained by the lower number of implants studied by Lindalen et al., the higher mean age in our study (63 vs. 61 years), and the fact that our follow-up was longer.

Inclusion of 2 more years did not change the overall conclusion that we came to in previous studies on reverse hybrid THAs, with similar 10-year survival for reverse hybrid and cemented THAs in patients between 55 and 65 years of age. In patients aged 65 years or more, however, the 10-year survival of the cemented implants was higher than that of the reverse hybrids (Mäkelä et al. 2014, Pedersen et al. 2014).

To study the effect of age on implant survival, we compared the 2 types of fixations in different age groups. The main findings were a 4 times higher risk of periprosthetic femoral fracture in patients with reverse hybrid THAs who were 65 years old or more, which increased to almost 6 times higher risk in patients over 74 years old. Periprosthetic femoral fractures are seen more often when using uncemented stems, especially during the first 6 months after surgery (Thien et al. 2014). In our study, two-thirds of the fractures were seen during the first 12 months after surgery. Fractures during surgery might occur either during broaching or when inserting the stem; to achieve primary stability of the implant, the broaching must be more aggressive than when using cement. In older patients, the bone is more fragile and the risk of cracks and fractures is therefore higher. On the other hand, cement reinforces the weak bone, making a stronger construct.

Reverse hybrid implant, female sex, and age over 74 years was the worst combination regarding the risk of periprosthetic femoral fractures. For women in general, the bone starts to become more fragile at an earlier age than for men and osteoporosis is more common in women than in men. We believe that this could be the main reason for the higher incidence of periprosthetic femoral fractures in this patient group. According to the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register (Annual Report 2013), periprosthetic femoral fractures might be under-reported—and especially those fractures that are treated only with internal fixation. We do, however, believe that this possible source of error would be distributed equally between cemented and reverse hybrid THAs.

We found no difference in the rate of revision due to deep infection between cemented and reverse hybrid THAs except in patients over 74 years, who had double the risk of revision. In a previous study from the NARA covering THAs operated until 2009, Dale et al. (2012) found no difference in the relative risk of revision due to infection between reverse hybrid and cemented THAs in general. Our findings in the oldest patients can be explained by the fact that there is often a correlation between higher age and a higher rate of comorbidity, and therefore a higher risk of infection. Later on, our dataset included also cases operated until 2013, which may have influenced the results. Antibiotic-loaded cement is believed to protect against infection (Dale et al. 2012), and since the stem is uncemented there might be a higher risk of infections in susceptible patients.

According to the National Joint Replacement Registry of Australia (2013), uncemented THAs have more early revisions than cemented ones, but from 8 years onwards the survival of uncemented THAs was better than that of cemented THAs.

In young patients, Havelin et al. (2000) found better performance of some uncemented stems than of cemented stems in the NAR, mainly because of less aseptic loosening. Hallan et al. (2007) showed in another study that included younger patients than those studied by us, that all uncemented stems that were frequently used at that time had a 10-year survival of more than 96% with this endpoint. It might be that our follow-up has been too short to show any benefits of the uncemented stems in reverse hybrid THAs. Since the data from the NARA do not distinguish between loosening of the stem and the cup, one should be careful when making any conclusions on this issue. Despite this, we believe that the higher incidence of aseptic loosening in patients aged 65 years or more could be related to inadequate primary fixation of the uncemented stems.

Since the Corail stem was used in most of the cup/stem combinations studied, differences in survival can most probably be explained by differences on the acetabular side. There was no statistically significant difference in survival when we compared the different combinations to all-cemented THAs for the entire period studied, except for one combination: Marathon/Corail. The median age of Marathon/Corail patients was 68 (60–78) years, as compared to 64 (57–72) years for all reverse hybrids. This might explain some of the difference, since age is one of the risk factors—especially for early revision in reverse hybrid THA. This is also supported by the findings when studying results for different time periods. Marathon/Corail had inferior results to those of cemented THAs only in the first postoperative period studied. Looking at the period 1–5 years post operatively, Corail/Marathon performed as well as cemented THAs.

In the first postoperative period (0–1 year of follow-up), all reverse hybrid combinations performed worse than cemented THAs except for 3 combinations: Reflection all-poly/Corail, Contemporary/Corail, and Lubinus/Spotorno. In the second period (1–5 years), we found no difference in survival between the different combinations of reverse hybrid THAs and cemented THAs. This confirms the fact that the poorer result with reverse hybrid THAs is mainly related to a higher rate of revisions within the first year after surgery. In the third period studied (> 5 years of follow-up), there was a trend showing better results for reverse hybrids than for cemented THA, but only the Elite/Corail combination performed statistically significantly better. The Reflection all-poly/Corail combination had inferior results to all other combinations after 5 years of follow-up. We believe that this was due to inferior long-term results for the Reflection all-poly cups with conventional polyethylene. Espehaug et al. (2009) published results for this cup in 2009 showing that it was inferior, and a later RSA study has shown high wear rates (Kadar et al. 2011).

The implant survival was not improved by the use of highly crosslinked polyethylene. This is different from what is reported in the annual report of the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (2013). It was found that crosslinking of liners for uncemented modular cups improved the medium-term results compared to conventional PE. Our follow-up was probably too short to show any difference. Furthermore, cemented cups may be less vulnerable to wear-related problems than uncemented ones (Clement et al. 2011).

That study was based on data from the NARA, but since reverse hybrid THA is mainly used in Norway and Sweden only, the study reflects the results mainly from 2 of the 4 countries in the NARA. This is a weakness of our study, and reflects one problem when combining databases from different countries. Another weakness is the fact that the same stem (Corail) was used in most of the reverse hybrid THAs.

The main conclusions from this study are as follows. (1) Reverse hybrid THA had inferior implant survival than cemented THA in patients aged 65 years or more, because the first concept entails a higher risk of early revision for periprosthetic femoral fracture in this age group, and especially in women. (2) In patients younger than 65 years, reverse hybrid THAs and all-cemented THAs were equally good options. (3) According to the results of this study, the increasing use of reverse hybrid THAs in elderly patients (at least 65 years of age) does not appear to be justified because of a higher rate of early postoperative complications.

HW wrote the manuscript. AMF preformed all the statistical analyses. LIH, GH, OF, ABP, SO, JK, GG, KM, AE, and LN contributed to planning, interpretation of data, and critical review of the manuscript.

We thank the surgeons in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden for conscientious reporting of THAs to their national registry, and the staff of all 4 Nordic national registries for their continuous work with quality assurance of registration.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry Annual Report 2013. https://aoanjrr.sahmri.com/annual-reports-2013 [Google Scholar]

- Clement N D, Biant L C, Breusch S J.. Total hip arthroplasty: to cement or not to cement the acetabular socket? A critical review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2011; 132(3): 411–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale H, Fenstad AM, Hallan G, Havelin L I, Furnes O, Overgaard S, Pedersen A B, Kärrholm J, Garellick G, Pulkkinen P, Eskelinen A, Mäkelä K, Engesæter L.. Increasing risk of prosthetic joint infection after total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2012; 83(5): 449–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espehaug B, Furnes O, Engesaeter L B, Havelin L I.. 18 years of results with cemented primary hip prostheses in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register: concerns about some newer implants. Acta Orthop 2009; 80(4): 402–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine J P, Gray R J.. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association. Taylor & Francis 1999; 94(446): 496–509. [Google Scholar]

- Hailer N P, Garellick G, Kärrholm J.. Uncemented and cemented primary total hip arthroplasty in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2010; 81(1): 34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallan G, Lie S A, Furnes O, Engesaeter L B, Vollset S E, Havelin L I.. Medium- and long-term performance of 11,516 uncemented primary femoral stems from the Norwegian arthroplasty register. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007; 89(12): 1574–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelin L I, Engesaeter L B, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Lie S A, Vollset S E.. The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register: 11 years and 73,000 arthroplasties. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71(4): 337–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelin L I, Espehaug B, Engesaeter L B.. The performance of two hydroxyapatite-coated acetabular cups compared with Charnley cups. From the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002; 84(6): 839–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelin L I. A Scandinavian experience of register collaboration: The Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association (NARA). J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93(Supplement 3): 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadar T, Hallan G, Aamodt A, Indrekvam K, Badawy M, Skredderstuen A, Havelin L I, Stokke T, Haugan K, Espehaug B, Furnes O.. Wear and migration of highly cross-linked and conventional cemented polyethylene cups with cobalt chrome or Oxinium femoral heads: A randomized radiostereometric study of 150 patients. J Orthop Res 2011; 29(8): 1222–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie S A, Engesæter L B, Havelin L I, Gjessing H K, Vollset S E.. Dependency issues in survival analyses of 55,782 primary hip replacements from 47,355 patients. Stat Med 2004; 23(20): 3227–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindalen E, Havelin L I, Nordsletten L, Dybvik E, Fenstad A M, Hallan G, Furnes O, Høvik Ø, Röhrl S M.. Is reverse hybrid hip replacement the solution? Acta Orthop 2011; 82(6): 639–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkelä K T, Eskelinen A, Paavolainen P, Pulkkinen P, Remes V.. Cementless total hip arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis in patients aged 55 years and older. Acta Orthop 2010; 81(1): 42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkelä K T, Matilainen M, Pulkkinen P, Fenstad A M, Havelin L, Engesaeter L, Furnes O, Pedersen A B, Overgaard S, Kärrholm, Malchau H, Garellick G, Ranstam J, Eskelinen A.. Failure rate of cemented and uncemented total hip replacements: register study of combined Nordic database of four nations. BMJ 2014; 348: f7592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally S A, Shepperd J A N, Mann C V, Walczak J P.. The results at nine to twelve years of the use of a hydroxyapatite-coated femoral stem. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000; 82-B(3): 378–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Arthroplasty Register Annual Report 2012. www.nrlweb.ihelse.net/Rapporter/Rapport2012.pdf

- Pedersen A B, Mehnert F, Havelin L I, Furnes O, Herberts P, Kärrholm J, Garellick G, Mäkelä K, Eskelinen A, Overgaard S.. Association between fixation technique and revision risk in total hip arthroplasty patients younger than 55 years of age. Results from the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014; 22(5): 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranstam J, Robertsson O.. Statistical analysis of arthroplasty register data. Acta Orthop 2010; 81(1): 10–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register Annual Report 2012. www.shpr.se/Libraries/Documents/arsrapport_2012_WEB.sflb.ashx

- Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register Annual Report 2013. www.shpr.se/Libraries/Documents/arsrapport_2013_3_WEB.sflb.ashx

- Thien T M, Chatziagorou G, Garellick G, Furnes O, Havelin L I, Mäkelä K, Overgaard S, Pedersen A, Eskelinen A, Pulkkinen P, Kärrholm J.. Periprosthetic femoral fracture within two years after total hip replacement: analysis of 43 Thien 7,629 operations in the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association database. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96(19): e167–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]