Abstract

Background and purpose

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) due to posttraumatic fracture osteoarthritis (PTFA) may be associated with inferior prosthesis survival. This study is the first registry-based study solely addressing this issue. Both indications and predictors for revision were identified.

Patients and methods

52,518 primary TKAs performed between 1997 and 2013 were retrieved from the Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register (DKR). 1,421 TKAs were inserted due to PTFA and 51,097 due to primary osteoarthritis (OA). Short-term (< 1 year), medium-term (1–5 years), and long-term (> 5 years) implant survival were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox regression after age stratification (< 50, 50–70, and >70 years). In addition, indications for revision and characteristics of TKA patients with subsequent revision were determined.

Results

During the first 5 years, TKAs inserted due to PTFA had a higher risk of revision than OA (with adjusted hazard ratio ranging from 1.5 to 2.4 between age categories). After 5 years, no significant differences in the risk of revision were seen between the groups. Infection and aseptic loosening were the most common causes of revision in both groups, but TKA instability was a more frequent indication for revision in the PTFA group. In both groups, the revision rates were higher with younger age and extended duration of primary surgery.

Interpretation

We found an increased risk of early and medium-term revision of TKAs inserted due to previous fractures in the distal femur and/or proximal tibia. Predictors of revision such as age <50 years and extended duration of primary surgery were identified, and revision due to instability occurred more frequently in TKAs performed due to previous fractures.

Fractures of the distal femur or proximal tibia are relatively common, accounting for 1.6% of the fractures admitted to a casualty department annually (Court-Brown and Caesar 2006). Of these, between 21% and 44% have been reported to develop posttraumatic fracture osteoarthritis (PTFA) (Honkonen 1995, Papadopoulos et al. 2002, Weiss et al. 2003a,b, Mehin et al. 2012). Hence, posttraumatic osteoarthritis (including PTFA) is estimated to account for 12% of all symptomatic arthritis (Brown et al. 2006). The risk of developing PTFA because of fractures around the knee is most likely related to altered knee mechanics, joint surface incongruence, and bone or soft-tissue damage (Furman et al. 2006, Piedade et al. 2013, Riordan et al. 2014). A total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is often indicated to relieve pain and improve function of knees with severe PTFA or primary osteoarthritis (OA).

Recent studies have investigated the outcome of TKA due to PTFA after fractures of the distal femur and/or proximal tibia when compared to primary OA (Papadopoulos et al. 2002, Haidukewych et al. 2005, Bala et al. 2015, Lizaur-Utrilla et al. 2015, Scott et al. 2015, Houdek et al. 2016). Most of the studies have been conducted on small cohorts and/or have been limited to a single institution, thus reducing the generalizability of the results. Still, the current consensus is that TKAs inserted due to PTFA have an increased risk of revision when compared to OA. The inferior survival is thought to be due to compromise of the soft-tissue envelope, poor bone quality, and extended procedures due to hardware retained from the fracture surgery (Roffi and Merritt 1990, Papadopoulos et al. 2002, Weiss et al. 2003a). To our knowledge, no large observational registry-based study has yet been conducted solely to confirm the inferior survival of TKA inserted due to PTFA. In addition to determining the survival, in this large registry-based study we compared the indications for revision between the revised TKAs to identify potential differences that might be explained by previous fractures and/or might be avoidable during primary operation. Finally, we analyzed characteristics of patients and surgery that may predict a subsequent revision.

Patients and methods

Study cohort

The present study was based on registrations in the Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register (DKR), which has prospectively collected data on knee arthroplasties inserted in Denmark (with a population of 5.6 million) since January 1, 1997. The DKR has recently been described as being applicable to epidemiological studies, with a reported registry completeness of 88% in 2010 rising to 97% in 2014 (Pedersen et al. 2012, DKR 2015). The data in the DKR are reported by all Danish TKA surgeons using a standardized form containing patient characteristics including Charnley class (Bjorgul et al. 2010), operation time, perioperative complications (fractures or tendon injuries), and the need for component supplementation including cones/sleeves, augments, or stems. Subsequent revisions are also registered in the DKR, and the indications for revision are grouped as aseptic loosening, pain, instability, infection, polyethylene failure (including both breakage and wear), secondary insertion of patella component, and other (including periprosthetic fractures). Only patients who received a conventional primary TKA from January 1, 1997 through December 31, 2013—due either to PTFA from distal femur or proximal tibia fractures (excluding secondary osteoarthritis from other causes) or to primary OA—were included. The DKR was linked to the Danish Civil Registry System (DCRS) by using the unique Danish civil registration number, which is part of all Danish registries. The DCRS has been collecting data on vital status and emigration for all Danish residents since its origin in 1968 (Schmidt et al. 2014). In patients with bilateral TKA, only the first TKA to be inserted was included to avoid potential problems regarding bilateral observations (Ranstam 2002). During the study period, 54,977 patients with primary TKA performed due to OA or PTFA were registered in the DKR. 2,459 of these patients (PTFA: 54; OA: 2,405) were excluded due to missing observations of possible confounders outlined in Table 1 (see Supplementary data). The influence of these patients was tested by creating dummy variables of the missing observations, and they were found to be randomly distributed. In addition, the inclusion of the patients who were removed did not alter the results of the study. Based on these analyses, the patients were excluded without further analysis. In total, 52,518 primary TKAs were included in this study. Of these, 1,421 (3%) were inserted due to PTFA and 51,097 (97%) were inserted due to OA.

Analyses and statistics

Revision for any cause was considered to be the primary endpoint, and TKA with no endpoint was censored at December 31, 2013. Follow-up was divided into short-term (< 1 year), medium-term (1–5 years), long-term (> 5 years), and cumulative (entire). The patients were divided in 3 age categories (< 50, 50–70, and >70 years). Kaplan-Meier (KM) analysis and Cox regression were used to estimate survival and hazard ratios (HRs) of TKAs inserted due to PTFA, with OA as reference (Ranstam et al. 2011a,b). HRs were adjusted for possible confounding from sex, weight, Charnley class (with class A as reference), perioperative complications, and the use of component supplementation. The confounders were chosen based on clinical experience and the previous literature (Khan et al. 2016). All covariates fulfilled the assumption of proportional hazards when tested by Schoenfeld residual test. The revised TKAs were grouped by the indication for revision. If more than 1 indication was registered, the revision was considered as a single endpoint but the revision contributed to the listed indication groups, so the number of causes of revision was higher than the number of revisions. Survival estimates were compared by log-rank test, categorical variables were compared by chi-squared test or Fischer’s exact test, and numeric variables were compared by Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Standard derivations (SDs) were clustered at the hospital level to shield against inter-hospital variations such as tradition in decision-making and surgeon experience. We calculated the 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values of ≤0.05 were regarded as being significant. Raw data were prepared using SAS 9.4 and the statistical analyses were performed using STATA14.

Ethics and funding

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (entry no. 2008-58-0028). The study was financed from the authors’ institutions. No competing interests declared.

Results

Characteristics of the patients and the surgery (Table 2)

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| < 50 years |

50–70 years |

> 70 years |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | PTFA | OA | PTFA | OA | PTFA | OA |

| Observations | 227 (14%) | 1.377 (86%) | 771 (3%) | 24,259 (97%) | 423 (2%) | 25,461(98%) |

| Mean follow-up, years | ||||||

| (range, days–years) | 6.1 (19–16.2) | 4.6 (14–16.7) | 6.0 (20–16.9) | 5.2 (1–17) | 5.8 (2–16.8) | 5.1 (1–17) |

| Revisionsa | 50 (22%)e | 154 (11%)e | 80 (10%) | 1,390 (6%) | 29 (7%) | 817 (3%) |

| Mean ageb | 42 (SD 6)e | 46 (SD 4)e | 60 (SD 6)e | 62 (SD 5)e | 77 (SD 5) | 77 (SD 5) |

| Sexa | ||||||

| Female | 88 (39%)e | 854 (62%)e | 408 (53%)e | 14,670 (60%)e | 311 (74%)d | 16,899 (66%)d |

| Fracture | ||||||

| Femoral | 63 (28%) | NA | 170 (22%) | NA | 67 (16%) | NA |

| Tibial | 164 (72%) | NA | 601 (78%) | NA | 356 (84%) | NA |

| Weight, kgb | 83 (SD 23)e | 92 (SD 21)e | 81 (SD 21)e | 88 (SD 20)e | 73 (SD 20)e | 79 (SD 18)e |

| Charnley class, na | ||||||

| A | 207 (91%)e | 796 (58%)e | 610 (79%)e | 10,710 (45%)e | 292 (69%)e | 10,639 (42%)e |

| B1 | 10 (4.5%)e | 350 (25%)e | 76 (10%)e | 8,351 (34%)e | 50 (12%)e | 8,715 (34%)e |

| B2 | 1 (0.5%)e | 158 (12%)e | 18 (2%)e | 3,971 (16%)e | 14 (3%)e | 4,327 (17%)e |

| C | 9 (4%)e | 73 (5%)e | 67 (9%)e | 1,227 (5%)e | 67 (16%)e | 1,780 (7%)e |

| Mean duration of | ||||||

| primary surgery, minb | 102 (SD 33)e | 73 (SD 24)e | 96 (SD 38)e | 73 (SD 22)e | 94 (SD 33)e | 72 (SD 21)e |

| Perioperative complicationsa | 2 (1%) | 10 (1%) | 28 (3.5%)e | 158 (0.5%)e | 10 (2.5%)e | 201 (1%)e |

| Component supplementationb | 43 (19%)e | 24 (1.5%)e | 129 (17%)e | 504 (2%)e | 92 (22%)e | 546 (2%)e |

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test.

Level of significance: c p < 0.05, dp < 0.01, ep < 0.001.

The PTFA group had longer follow-up than the OA group, irrespective of the age category. In general, the length of follow-up ranged from 4.6 to 6.1 years. The proportion of females was slightly lower in the PTFA group, but varied between each age category. The patients in the PTFA group weighed an average of 6–9 kg less than in the OA group (p < 0.001). In general, more patients in the PTFA group belonged to Charnley class A, but the proportion of patients in Charnley class C increased with age in the PTFA group whereas it remained similar in the OA group. The mean operating time was longer in the PTFA group (ranging from 94 to 102 min, as compared to 72–73 min in the OA group) (p < 0.001). Perioperative complications were more frequent in the PTFA group in patients over 50 years of age, and component supplementation was needed almost 10 times as often in the PTFA group than in the OA group, irrespective of age category.

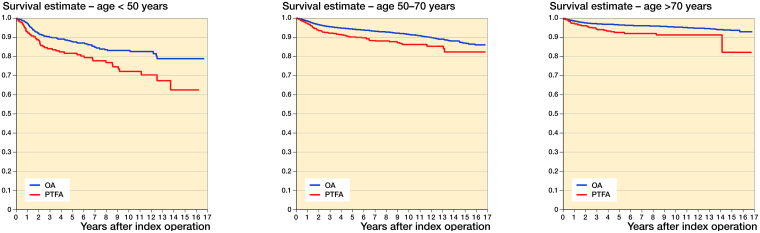

Survival function and hazard ratios (Figure 1 and Table 3, see Supplementary data)

Figure 1.

Survival estimation by Kaplan-Meier method for TKA inserted due to PTFA (red line) and due to primary OA (blue line).

A. Patients younger than 50 years. A significant difference was found by log-rank test (p = 0.001). The estimated survival in the PTFA group at 1, 5, and 10 years following primary operation was 0.93 (CI: 0.88–0.95), 0.82 (CI: 0.76–0.86), and 0.72 (CI: 0.64–0.79), respectively. Similarly, the corresponding survival rates in the OA group were 0.97 (CI: 0.96–0.98), 0.88 (CI: 0.86–0.89), and 0.83 (CI: 0.80–0.86).

B. Patients aged between 50 and 70 years. A significant difference was found by log-rank test (p < 0.001). The estimated survival at 1, 5, and 10 years following primary operation in the PTFA group was 0.97 (CI: 0.96–0.98), 0.90 (CI: 0.87–0.92), and 0.86 (CI: 0.83–0.89). Similarly, the 1-, 5-, and 10-year survival in the OA group was 0.98 (CI: 0.98–0.99), 0.94 (CI: 0.94–0.95), and 0.91 (CI: 0.91–0.92).

C. Patients aged more than 70 years. A significant difference was found by log-rank test (p < 0.001). The estimated survival at 1, 5, and 10 years following primary operation in the PTFA group was 0.97 (CI: 0.95–0.99), 0.93 (CI: 0.89–0.95), and 0.91 (CI: 0.87–0.94). Similarly, the 1-, 5-, and 10-year survival in the OA group was 0.99 (CI: 0.98–0.99), 0.97 (CI: 0.96–0.97), and 0.95 (CI: 0.95–0.96).

There was a higher incidence of revision in the PTFA group, for all age categories (p ≤ 0.001 for all comparisons).

Age <50 years – In this age category, 50 TKAs (22%) in the PTFA group and 154 TKAs (11%) in the OA group were revised. The temporal distribution of revisions in the PTFA group was 16 (7%) within the first year, 21 (9%) from the first year until the fifth year, and 13 (6%) following the fifth year after surgery. Likewise, the distribution of revisions in the OA group was 36 (2.5%) during the first year, 96 (7%) from the first until the fifth year, and 22 (1.5%) following the fifth year after primary operation. This corresponds to an adjusted HR of 1.6 (95% CI: 1.1–2.2; p = 0.01) for the PTFA group relative to the OA group, for the entire follow-up, with the highest revision risk occurring during the first year after TKA (adjusted HR =2.5, 95% CI: 1.4–4.5, p = 0.002). After the first year, the HRs were similar between the 2 groups.

Age between 50 and 70 years – In this age category, 80 TKAs (10%) in the PTFA group and 1,390 TKAs (6%) in OA group were revised. The temporal distribution of revisions in the PTFA group was 22 (2.5%) within the first year, 43 (5.5%) from the first until the fifth year, and 15 (2%) following the fifth year after primary surgery. Similarly, the distribution in the OA group was 380 (2%) within the first year, 749 (3%) from the first until the fifth year, and 261 (1%) following the fifth year after operation. Again, an increased risk of revision was found in the PTFA group relative to the OA group, with an estimated adjusted HR of 1.5 (95% CI: 1.2–1.8; p < 0.001) for the entire follow-up. Again, the highest HR was for short-term follow-up (adjusted HR =1.6, 95% CI: 1.1–2.4, p = 0.02), and following the fifth year after the primary operation, the HRs for revision were similar between the 2 groups.

Age >70 years – In this age category, 29 TKAs (7%) in the PTFA group and 817 TKAs (3%) in the OA group were revised. The temporal distribution of revisions in the PTFA group was 10 (2.5%) within the first year, 16 (3.5%) from the first until the fifth year, and 3 (1%) following the fifth year after the primary operation. Likewise, the distribution of revisions in the OA group was 343 (1.2%) during the first year after operation, 377 (1.4%) from the first until the fifth year after operation, and 97 (0.4%) following the fifth year after the primary operation. The highest adjusted HR for the entire follow-up was found in this age category (HR =1.9, 95% CI: 1.4–2.7; p < 0.001). Surprisingly, this was due to a high risk of revision in the medium-term follow-up (adjusted HR =2.4, 95% CI: 1.5–3.8; p < 0.001). Again, following the fifth year of primary operation the HRs were similar between the 2 groups.

Indications for revision (Table 4, see Supplementary data)

In general, revisions were more frequent in the PTFA group, with an almost 3-fold increase in incidence proportion for infection (3.2% vs. 1.4%), aseptic loosening (3.2% vs. 1%), and instability (3.5% vs. 1.1%) of the inserted primary TKA during the entire follow-up. The largest difference between the groups was found in revisions due to instability and infection, with infection as the leading cause in both, and with instability as a notably more frequent indication in the PTFA group (23% vs. 17%). During short-term follow-up, infection was the most frequent indication for revision in the OA group (35%), but had the same frequency as instability in the PTFA group (32% for both indications). In the medium-term follow-up, aseptic loosening became more frequent and, together with infection and instability, was the most frequent indication in the PTFA group (26% vs. 25% and 20%, respectively). A similar shift occurred in the OA group, where aseptic loosening alone was the most frequent indication during medium-term follow-up (29%). In general, revisions were less frequent and indications were more comparable during long-term follow-up, with aseptic loosening being the most frequent indication in both groups (PTFA: 36%; OA: 34%).

Characteristics of patients and operations with subsequent revision (Table 5, see Supplementary data)

Patients with subsequent revision were younger in both groups, with the largest difference of means in the PTFA group (6 years; p < 0.001). The average duration of primary surgery was longer in both groups, and again the largest difference of means was found in the PTFA group (106 min vs. 95 min; p < 0.01). Some other characteristics differed statistically significantly in the OA group, but most were not of clinical interest—except the incidence of perioperative complications, which was almost twice as frequent in revised TKAs (1.2% vs. 0.7%; p < 0.01), and increased need for component supplementation (3% vs. 2%; p < 0.05).

Sensitivity analysis

The adjusted hazard ratios were calculated both as presented, and when adjusted only for sex, weight, and Charnley class. This was due to the possible connection between perioperative complications and the need for additional component supplementation, and PTFA. In general, the adjusted hazard ratios were higher when less covariates were used, but this was not of major clinical importance (mean difference =0.11, range: 0.02–0.39) and without any change in the level of statistical significance (data not shown). In addition, we conducted cumulative incidence function with death as competing risk, and Fine and Grey analysis to estimate the adjusted HR due to the long-term follow-up in an old population. When death is a competing risk, Kaplan-Meier analyses (KM) might lead to overestimation of the risk of revision when compared to analytical approaches that account for competing risks (Gillam et al. 2010). However, since KM and Cox regression are more widely used in the orthopedic literature, and there was only a minor—clinically insignificant—difference in the estimated survival using these 2 methods, we have presented results based on KM and Cox regression.

Discussion

In this population-based study based on 52,518 patients in the Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register (DKR), we found inferior survival of TKAs that were inserted due to PTFA after distal femur or proximal tibia fractures, relative to primary OA. Not surprisingly, the highest cumulative failure rate was found in the youngest age group and the lowest rate was found in the highest age group for both types of arthritis. This may have been due to an inferior threshold for revision, as well as increased wear in TKAs inserted in younger patients. Surprisingly, the association between PTFA and revision risk in the entire follow-up period was strongest in patients aged over 70 years, which might be explained by the higher number of Charnley class C patients and a possibly inferior bone quality in the PTFA group compared to the OA group. This variance indicated a compromised active daily living in a frail group of patients, and might result in an increased risk of complications such as secondary infections or periprosthetic fractures. In all age categories, the increased risk of revision was most pronounced during short- and medium-term follow-up and a similar risk of revision between the groups was found beyond the fifth year after primary operation.

The overall inferior survival is in accordance with several other studies addressing the survival of TKA inserted in knees with either PTFA or posttraumatic osteoarthritis in general (Lonner et al. 1999, Papadopoulos et al. 2002, Weiss et al. 2003a, Haidukewych et al. 2005, Abdel et al. 2015, Lizaur-Utrilla et al. 2015, Scott et al. 2015). In a recent study, Houdek et al. (2016) reported an adjusted HR of 2.2 (adjusted for multiple preoperative factors including sex, age, and weight) observed in a single-center retrospective cohort study involving 531 cases with a mean follow-up of 6 years. Bala et al. (2015) published a large retrospective database study involving 3,509 patients (with an average follow-up of 5 years) and reported an odds ratio of 1.2 for revision and an increased risk of some postoperative complications, such as infections and wound complications. Furthermore, 2 recent studies based on data from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register concluded that there was a similar increased risk of revision—either due to infection or for any reason—in knees with posttraumatic osteoarthritis when compared to OA (Jamsen et al. 2009, Julin et al. 2010). Our study complements these studies by concentrating solely knees with previous fractures in a large population and also by reporting an equal risk of revision following the fifth postoperative year for both types of arthritis, irrespective of patient age. Furthermore, our study revealed a higher occurrence of instability in the PTFA group, which may have been due to the preceding injury—resulting in a reduced quality of the bones and ligaments and also the need for larger surgical exposure to deal with retained surgical hardware (Saleh et al. 2001). To try to prevent subsequent revisions due to instability, the surgeon must meticulously balance the knee during primary surgery and choose optimal implants in cases where the soft-tissue conditions do not allow satisfactory balancing of the knee (Lombardi et al. 2014). The main cause of revisions shifted towards aseptic loosening during the later follow-up periods, making it the most common cause of revision during long-term follow-up in both groups. A similar observation was recently reported in a major review study conducted by Khan et al. (2016), where a shift from infection to aseptic loosening occurred 2.5 years after the primary TKA operation.

Several predictors for revision of TKAs performed due to PTFA have been suggested in the recent literature. Shearer et al. (2013) found the complexity of the deformity following fractures to be a major predictor, and specially noted combined tibial and femoral deformities as a major predictor of later revision. In addition, Parratte et al. (2011) reported malalignment, joint fibrosis, insufficiency of the collateral ligaments, and bone/cartilage destruction as being other main predictors of an inferior outcome in knees with intraarticular malunion. They also reported that additional component supplementation was needed in 40% of the cases. In our study, additional component supplementation was used far more often when TKA was performed due to PTFA, which might indicate an inferior bone and/or ligament condition in these patients. However, no substantial increase in the risk of revision was found when component supplementation was needed, and there was no difference in this need between revision and primary TKAs performed due to PTFA (data not shown). The comparison between patients with and without revision revealed some interesting additional predictors of later revision—such as younger age, extended operation time, and perioperative complications. The extended operation time and perioperative complications were more pronounced in the PTFA group, indicating more demanding surgery associated with a higher revision rate in this group.

Our study had some limitations. Firstly, the diagnosis reported in the DKR has not yet been validated, so there is the possibility of misclassification. Secondly, even though Charnley class is an accepted assessment of patients’ comorbidity (Greene et al. 2015), it does not give comprehensive information about potential systemic diseases such as liver cirrhosis or diabetes mellitus, which have been shown to influence the survival of TKA in other studies (Bolognesi et al. 2008, Bjorgul et al. 2010, Deleuran et al. 2015). Thirdly, selection bias and information bias is often found in this type of study, although the accuracy and completeness of the registry used have been validated (Pedersen et al. 2012). Finally, the long study period and the pooling of all sorts of TKAs may have masked the specific outcome of certain type(s) of TKA(s) for certain time periods (Robertsson et al. 2001).

In summary, this registry-based study confirmed the inferior survival of TKA inserted due to PTFA from previous fractures of the distal femur or proximal tibia. However, the study also revealed that following the fifth year of operation, the risk of revision was like that of TKAs inserted due to primary OA. Instability was a major cause of revision, highlighting the importance of meticulous preoperative planning.

Supplementary data

Tables 1 and 3–5 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1290479.

AG, PTN, AK, and MU planned the study. SH and AG analyzed the data in collaboration with AP. AG wrote the manuscript in collaboration with the other authors.

Supplementary Material

References

- Abdel M P, von Roth P, Cross W W, Berry D J, Trousdale R T, Lewallen D G.. Total knee arthroplasty in patients with a prior tibial plateau fracture: a long-term report at 15 years. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30(12): 2170–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bala A, Penrose C T, Seyler T M, Mather R C 3rd, Wellman S S, Bolognesi M P.. Outcomes after total knee arthroplasty for post-traumatic arthritis. Knee 2015; 22(6): 630–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorgul K, Novicoff W M, Saleh K J.. Evaluating comorbidities in total hip and knee arthroplasty: available instruments. J Orthop Traumatol 2010; 11(4): 203–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolognesi M P, Marchant M H Jr., Viens N A, Cook C, Pietrobon R, Vail T P.. The impact of diabetes on perioperative patient outcomes after total hip and total knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty 2008; 23(6 Suppl 1): 92–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T D, Johnston R C, Saltzman C L, Marsh J L, Buckwalter J A.. Posttraumatic osteoarthritis: a first estimate of incidence, prevalence, and burden of disease. J Orthop Trauma 2006; 20(10): 739–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Court-Brown C M, Caesar B.. Epidemiology of adult fractures: a review. Injury 2006; 37(8): 691–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleuran T, Vilstrup H, Overgaard S, Jepsen P.. Cirrhosis patients have increased risk of complications after hip or knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2015; 86(1): 108–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DKR Annual Report. https://www.sundhed.dk/content/cms/99/4699_knæallop.pdf: Danish Knee Arthroplasty Registry; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Furman B D, Olson S A, Guilak F.. The development of posttraumatic arthritis after articular fracture. J Orthop Trauma 2006; 20(10): 719–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillam M H, Ryan P, Graves S E, Miller L N, de Steiger R N, Salter A.. Competing risks survival analysis applied to data from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Acta Orthop 2010; 81(5): 548–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene M E, Rolfson O, Gordon M, Garellick G, Nemes S.. Standard comorbidity measures do not predict patient-reported outcomes 1 year after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015; 473(11): 3370–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidukewych G J, Springer B D, Jacofsky D J, Berry D J.. Total knee arthroplasty for salvage of failed internal fixation or nonunion of the distal femur. J Arthroplasty 2005; 20(3): 344–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honkonen S E. Degenerative arthritis after tibial plateau fractures. J Orthop Trauma 1995; 9(4): 273–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houdek M T, Watts C D, Shannon S F, Wagner E R, Sems S A, Sierra R J.. Posttraumatic total knee arthroplasty continues to have worse outcome than total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty 2016; 31(1): 118–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamsen E, Huhtala H, Puolakka T, Moilanen T.. Risk factors for infection after knee arthroplasty. A register-based analysis of 43,149 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009; 91(1): 38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julin J, Jamsen E, Puolakka T, Konttinen YT, Moilanen T.. Younger age increases the risk of early prosthesis failure following primary total knee replacement for osteoarthritis. A follow-up study of 32,019 total knee replacements in the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2010; 81(4): 413–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M, Osman K, Green G, Haddad F S.. The epidemiology of failure in total knee arthroplasty: avoiding your next revision. Bone Joint J 2016; 98-B (1 Suppl A): 105–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizaur-Utrilla A, Collados-Maestre I, Miralles-Munoz F A, Lopez-Prats F A.. Total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis secondary to fracture of the tibial plateau: a prospective matched cohort study. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30(8): 1328–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi A V Jr., Berend K R, Adams J B.. Why knee replacements fail in 2013: patient, surgeon, or implant? Bone Joint J 2014; 96-B (11 Supple A): 101–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonner J H, Pedlow F X, Siliski J M.. Total knee arthroplasty for post-traumatic arthrosis. J Arthroplasty 1999; 14(8): 969–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehin R, O’Brien P, Broekhuyse H, Blachut P, Guy P.. Endstage arthritis following tibia plateau fractures: average 10-year follow-up. Can J Surg 2012; 55(2): 87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos E C, Parvizi J, Lai C H, Lewallen D G.. Total knee arthroplasty following prior distal femoral fracture. Knee 2002; 9(4): 267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parratte S, Boyer P, Piriou P, Argenson J N, Deschamps G, Massin P.. Total knee replacement following intra-articular malunion. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2011; 97 (6 Suppl): S118–S23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen A B, Mehnert F, Odgaard A, Schroder H M.. Existing data sources for clinical epidemiology: The Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register. Clin Epidemiol 2012; 4: 125–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piedade S R, Pinaroli A, Servien E, Neyret P.. TKA outcomes after prior bone and soft tissue knee surgery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013; 21(12): 2737–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranstam J. Problems in orthopedic research: dependent observations. Acta Orthop Scand 2002; 73(4): 447–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranstam J, Karrholm J, Pulkkinen P, Makela K, Espehaug B, Pedersen A B, Mehnert F, Furnes O.. Statistical analysis of arthroplasty data. I. Introduction and background. Acta Orthop 2011a; 82(3): 253–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranstam J, Karrholm J, Pulkkinen P, Makela K, Espehaug B, Pedersen AB, Mehnert F, Furnes O.. Statistical analysis of arthroplasty data. II. Guidelines. Acta Orthop 2011b; 82(3): 258–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan E A, Little C, Hunter D.. Pathogenesis of post-traumatic OA with a view to intervention. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2014; 28(1): 17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, Knutson K, Lewold S, Lidgren L.. The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register 1975-1997: an update with special emphasis on 41,223 knees operated on in 1988-1997. Acta Orthop Scand 2001; 72(5): 503–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roffi R P, Merritt P O.. Total knee replacement after fractures about the knee. Orthop Rev 1990; 19(7): 614–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh K J, Sherman P, Katkin P, Windsor R, Haas S, Laskin R, Sculco T.. Total knee arthroplasty after open reduction and internal fixation of fractures of the tibial plateau: a minimum five-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001; 83-A (8):1144–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sorensen H T.. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol 2014; 29(8): 541–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott C E, Davidson E, MacDonald D J, White T O, Keating J F.. Total knee arthroplasty following tibial plateau fracture: a matched cohort study. Bone Joint J 2015; 97-B (4): 532–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer D W, Chow V, Bozic K J, Liu J, Ries M D.. The predictors of outcome in total knee arthroplasty for post-traumatic arthritis. Knee 2013; 20(6): 432–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss N G, Parvizi J, Hanssen A D, Trousdale R T, Lewallen D G.. Total knee arthroplasty in post-traumatic arthrosis of the knee. J Arthroplasty 2003a; 18(3 Suppl 1): 23–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss N G, Parvizi J, Trousdale R T, Bryce R D, Lewallen D G.. Total knee arthroplasty in patients with a prior fracture of the tibial plateau. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003b; 85-A (2): 218–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.