Neglected traumatic dislocations of the hip are rarely seen in high-income countries, and the modern literature is limited on the subject. Reports on neglected anterior hip dislocations are especially scarce. At Kamuzu Central Hospital, in Lilongwe, Malawi, we have treated 4 patients for neglected traumatic dislocation of the hip over the last 3 years. Open reduction is difficult in these cases using traditional approaches, and this has resulted in the recommendation of salvage procedures such as intertrochanteric osteotomy (Hamada 1957, Aggarwal and Singh 1967) or modified excision arthroplasty (Nagi et al. 1992).

In 2013, we saw a 50-year-old builder who had fallen from a roof of a house and landed on his feet with an extended hip. According to the patient, a radiograph was obtained at a district hospital, but it was described as normal and he was sent home. He was seen at Kamuzu Central Hospital 4 months later with a painful right hip that was held in extension and external rotation. A pelvic radiograph revealed an anterior pubic hip dislocation. Open reduction was attempted with an anterior approach, but it was not possible for us to get good exposure of the acetabulum with the dislocated femoral head and neck covering the acetabulum, without substantial soft tissue release. We therefore ended up opting for a modified excision arthroplasty as recommended by Nagi et al. (1992). When seen at follow-up approximately 3 months after surgery, the patient was still using 2 crutches and had pain and instability of the hip if he tried to walk without support. As is so often the case in our setting (Young et al. 2013), the patient was lost to follow-up after this.

In September 2014, SY heard Dr Duane Anderson present his experiences from Ethiopia using the Bernese trochanteric flip osteotomy (Ganz et al. 2001) for neglected traumatic posterior hip dislocations. We have since used this method successfully on 2 male patients with neglected posterior hip dislocations (3 and 4 months after trauma), and we have become convinced that this is the approach of choice for open reduction of neglected traumatic hip dislocations. In both of these cases, the approach gave the necessary exposure of the acetabulum to remove all the firm scar tissue that filled it. In the first case, the labrum was inverted into the acetabulum and needed to be cut and everted to allow reduction. The approach preserves the blood supply to the femoral head, if it is not already damaged at the time of injury. By drilling a small hole in the femoral head at the border of the joint cartilage, one can assess whether there is a viable blood supply to the head and whether this changes after reduction. In these 2 cases, reduction was possible without undue force. In the first case, there was no bleeding from the drill hole in the femoral head. The patient quickly recovered and was discharged after a few days with partial weight bearing axilla crutches. The patient unfortunately never came back for review. The second patient had good bleeding from the drill hole before and after reduction. He was reviewed 3 and 8 months later and made a full recovery. Radiographs showed no sign of avascular necrosis or osteoarthritis at the last review.

When we received a 51-year-old man with a 6-week-old neglected anterior pubic dislocation in November 2015, we thought that the approach would be worth using in this case also. The injury had happened as he was walking home in the dark and fell into a well, falling backwards with hyperextension of the hip. He was bedridden at home without being able to look after himself and was brought in by family members.

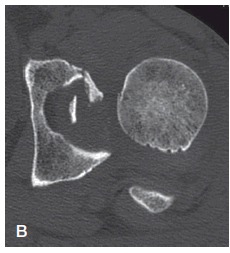

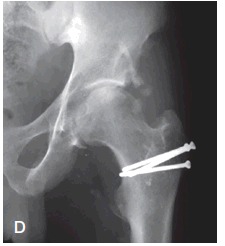

At this point, the hospital had not had a working X-ray machine for 4 months, but the patient had a radiograph from a district hospital confirming the diagnosis and showing some small bone fragments in the acetabulum (Figure). Our CT machine was still working at the time, and a CT scan confirmed that there were several small fragments from the anterior lip lying in the acetabulum. 3D reconstructions showed how the dislocated proximal femur lay in the way of good exposure of the acetabulum with traditional anterior and lateral approaches. We worried that the external rotation of the hip would make the trochanteric flip osteotomy impossible, but after the spinal anesthesia was administered, the leg could be internally rotated to almost the neutral position and this turned out not to be a problem. The patient was placed in the lateral position and a digastric trochanteric flip osteotomy as described by Ganz was performed (Ganz et al. 2001). A 2.5-mm drill hole at the edge of the femoral head cartilage confirmed that the circulation of the femoral head was intact. Good exposure of the acetabulum revealed several fragments from the anterior lip still attached to an almost totally detached anterolateral labrum. The totally avulsed anterolateral labrum and fragments were removed along with some soft, immature scar tissue that filled the acetabulum, and the acetabulum was irrigated to remove any remaining debris. The anteromedial labrum was better preserved and included another small acetabular edge fragment that was retained. Reduction was easily achieved. The hip was stable in extension with neutral rotation, but it re-dislocated with full extension and external rotation when tested before repair of the trochanter. The osteotomized trochanter was fixed with 3 small fragment cortex screws. The patient was kept in bed for 1 week postoperatively with the injured leg on a Braun frame, to hold the hip in neutral rotation and slight flexion. He was mobilized with non-weight-bearing axilla crutches for 6 weeks.

The patient was seen 3 and 7 months postoperatively. He was then walking without crutches, with a normal gait and without pain. There was a negative Trendelenburg test, no tenderness over the trochanter, and full, painless range of motion at the hip. The AP pelvic radiograph at 7-month follow-up showed some calcification of the periarticular soft tissues, but maintained joint space height and no signs of avascular necrosis.

A 51-year-old man with 6-week-old anterior hip dislocation. Bone fragments can be seen lying in the acetabulum.

CT image confirming dislocation and fracture of the anterior acetabular rim.

3D CT image before reduction showing how the proximal femur covers the acetabulum in anterior dislocations, making a lateral approach difficult also.

7 months postoperatively. The joint space is preserved and there is no sign of avascular necrosis. Some periarticular soft tissue calcifications can be seen.

Discussion

Sir Astley Cooper (1768–1841) gave an accurate account of neglected traumatic hip dislocations nearly 200 years ago in his “A treatise on dislocations, and on fractures of the joints”, first published in 1822 in London (Cooper 1822). He classified hip dislocations as “upwards, or onto the dorsum ilii”, “backwards, or into the ischiatic notch”, “downwards, or into the foramen ovale” (obturator foramen), and anterior or “on the pubes”, and estimated their relative frequency to be 60% (“dorsum ilii”), 25% (“ischiatic”), 10% (obturator), and 5% (pubic). This is remarkably consistent with more modern research from the twentieth century giving estimates of anterior dislocations (usually combining both pubic and obturator dislocations, and therefore less precise than Sir Astley Cooper) as between 7% and 13% (Thompson and Epstein 1951, Stewart and Milford 1954, Brav 1962, Lima et al. 2014). However, most present-day surgeons would probably agree that Astley Cooper’s posterior and ischiatic dislocations are variations of the same and can both be described as posterior.

Very little has been written about neglected traumatic hip dislocations, and what has is mostly from the 1950s to the 1980s. Even less is to be found about neglected anterior—or pubic—dislocations. Most authors have grouped obturator and pubic dislocations under a common heading as “anterior” (Hamada 1957, Aggarwal and Singh 1967, Nagi et al. 1992, Pai 1992). In our opinion, the term anterior dislocation of the hip should be reserved for true anterior, or pubic, dislocations as described by Cooper. Neglected traumatic hip dislocations (not counting acetabular floor fractures with central dislocation) should be classified into 1 of these 3 clinically useful groups: anterior (pubic), posterior, and obturator.

Of the few cases of neglected anterior dislocations published, Hamada (1957) reported 4 cases that were actually obturator dislocations, 1 of them due to a neglected septic hip. He used a proximal intertrochanteric osteotomy and a hip spica for 3–4 months to correct the hip deformity, and reported improvement in gait and posture.

Aggrarwal and Singh (1967) reported 7 anterior dislocations, only 1 of which was an actual anterior pubic dislocation. This hip had been dislocated for 13 months and was treated by “Arthroplasty. The articular cartilage was shaved off the femoral head, covered with fascia lata and reduced into the acetabulum.” The patient improved for 1 year but then deteriorated, and radiographs “showed absorption of the femoral head”—a probable case of avascular necrosis.

Pai (1992) reported 3 of 29 neglected dislocations to be anterior but did not define whether they were pubic or obturator. 1 was only 3 weeks old, closed reduction was achieved, and the patient made a “satisfactory” recovery. The second failed a regimen of “heavy traction” for several weeks and an unspecified open reduction was done. The patient had a “satisfactory” result. The last patient had a Girdlestone excision arthroplasty and did badly.

Nagi et al. (1992) reported 4 neglected anterior dislocations, arguing for the use of a modified excision arthroplasty retaining the femoral neck by performing a subcapital osteotomy to retain the possibility of a total hip replacement at a later stage. However, both patients who received this treatment had obturator dislocations. Of the 2 actual anterior (pubic) dislocations, 1 was treated with a subtrochanteric osteotomy, and ended up with a “pronounced limp and 7.5 cm shortening”. The other was treated with open reduction through an anterior Smith-Petersen approach. He had reduced range of motion and a painful hip at 10-month follow-up. Despite the fact that the authors’ recommended technique was never used by them in true anterior dislocations, this method is presented in textbooks as an option for neglected anterior dislocations (Canale and Beaty 2008).

More recently, however, Alva et al. (2013) reported a 5-month-old neglected anterior dislocation of the hip in a 25-year-old man. Avascular necrosis was diagnosed preoperatively on an MRI scan. A modified Girdlestone procedure as described by Nagi et al. (1992) was performed, and at 3-year follow-up the patient had a “fairly stable hip” and only 2.5 cm shortening.

Gupta and Shravat (1977) used “heavy traction” with 7–18 kg skeletal traction and sedation of 7 patients for up to 20 days, and achieved reduction in 6 of the patients. The successful reductions were in patients with dislocations that were less than 3 months old.

Since the detailed description of the anatomy of the blood supply to the femoral head and the technique for safe “surgical dislocation of the adult hip” by Ganz and the team in Bern (Gautier et al. 2000, Ganz et al. 2001), the Bernese trochanteric flip osteotomy for approach to the hip has increasingly been used in difficult cases of acute fracture dislocations of the hip. The approach preserves the blood supply to the femoral head and gives ample exposure of both the head and the acetabulum (Tannast et al. 2009, Keel et al. 2010, 2012), allowing removal of the scar tissue that fills it after about 3 months (Cooper 1822, Mikhail 1956, Nixon 1976). Despite our limited experience, we recommend attempting this approach in both posterior and anterior neglected traumatic hip dislocations.

We have not treated any neglected obturator dislocations at our institution. However, the few cases we have seen when they present acutely have not had an extreme external rotation and, in theory at least, a trochanteric flip osteotomy should also be possible in these patients. Judging from the literature, these patients often appear to have extensive ossification surrounding the femoral head, producing a neo-acetabulum (Cooper 1822, Mikhail 1956, Aggarwal and Singh 1967). Removal of this and the scar tissue in the acetabulum should be possible through the Bernese approach.

Our patient only had 7 months of follow-up, and it is possible that he could develop late complications such as avascular necrosis or osteoarthritis. However, the head was found to be viable intraoperatively, and even if he should develop 1 of these complications he will still have a better functioning hip and a more normal anatomy that is suited to THR or arthrodesis at a later stage. It is our opinion that open reduction using the Bernese trochanteric flip approach is a far better solution to this difficult problem than previously suggested heavy traction regimens (Gupta and Shravat 1977) and salvage operations, and we recommend that this should be attempted before resorting to intertrochanteric osteotomies or excision arthroplasties.

SY treated all 4 patients, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and performed revisions. LB treated 2 of the patients and revised the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the interpretation and discussion of the findings and the available literature.

References

- Aggarwal N D, Singh H.. Unreduced anterior dislocation of the hip. Report of seven cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1967; 49 (2): 288–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alva A, Shetty M, Kumar V.. Old unreduced traumatic anterior dislocation of the hip. BMJ Case Rep 2013. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-008068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brav E A. Traumatic dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg 1962; 44 (6): 1115–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Canale S T, Beaty J H (Eds.) Old unreduced dislocations In: Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. 11th ed., Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper S A. On dislocations of the hip-joint In: A Treatise on Dislocations, and on Fractures of the Joints. Paternoster Row, London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown; 1822. [Google Scholar]

- Ganz R, Gill TJ, Gautier E, Ganz K, Krügel N, Berlemann U.. Surgical dislocation of the adult hip a technique with full access to the femoral head and acetabulum without the risk of avascular necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001; 83 (8): 1119–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier E, Ganz K, Krügel N, Gill T, Ganz R.. Anatomy of the medial femoral circumflex artery and its surgical implications. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000; 82 (5): 679–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R C, Shravat B P.. Reduction of neglected traumatic dislocation of the hip by heavy traction. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1977; 59 (2): 249–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada G. Unreduced anterior dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1957; 39-B (3): 471–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel M J, Bastian J D, Büchler L, Siebenrock K A.. Surgical dislocation of the hip for a locked traumatic posterior dislocation with associated femoral neck and acetabular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010; 92 (3): 442–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel M J, Ecker T M, Siebenrock KA, Bastian JD.. Rationales for the Bernese approaches in acetabular surgery. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2012; 38 (5): 489–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima L C, Nascimento R A, Almeida V M T, Façanha Filho F A M.. Epidemiology of traumatic hip dislocation in patients treated in Ceará, Brazil. Acta Ortop Bras 2014; 22 (3): 151–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhail I K. Unreduced traumatic dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1956; 38-B (4): 899–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagi O N, Dhillon M S, Gill S S.. Chronically unreduced traumatic anterior dislocation of the hip: a report of four cases. J Orthop Trauma 1992; 6 (4): 433–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon J R. Late open reduction of traumatic dislocation of the hip. Report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1976; 58 (1): 41–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai V S. The management of unreduced traumatic dislocation of the hip in developing countries. Int Orthop 1992; 16 (2): 136–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart M J, Milford L W.. Fracture-dislocation of the hip; an end-result study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1954; 36 (A:2): 315–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannast M, Mack P W, Klaeser B, Siebenrock KA.. Hip dislocation and femoral neck fracture: decision-making for head preservation. Injury 2009; 40 (10): 1118–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson V P, Epstein H C.. Traumatic dislocation of the hip; a survey of two hundred and four cases covering a period of twenty-one years. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1951; 33-A (3): 746–78; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young S, Banza L N, Hallan G, Beniyasi F, Manda K G, Munthali B S, et al. . Complications after intramedullary nailing of femoral fractures in a low-income country. Acta Orthop 2013; 84 (5): 460–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]