Abstract

Introduction:

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a microvascular complication of diabetes. DN is clinically manifested as an increase in urine albumin excretion. Total white blood cell count is a crude but sensitive indicator of inflammation and studied in many cardiac and noncardiac diseases as an inflammatory marker such as acute myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure. In this study, the association of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) with DN is studied.

Patients and Methods:

It is an observational cross-sectional study. Totally 115 diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus patients were registered in this study. NLR was calculated by analyzing differential leukocyte count in complete blood picture. Albuminuria was tested by MICRAL-II TEST strips by dipstick method.

Results:

Totally 115 diabetic patients were registered. About 56 patients had DN and 59 had normal urine albumin. Mean NLR for a normal group is 1.94 ± 0.65 and in DN group is 2.83 ± 0.85 which was highly significant (P < 0.001). Estimated glomerular filtration rate (P = 0.047) and serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase (P < 0.001) were also significant.

Conclusion:

The results of our study show that there was a significant relation between NLR and DN. Therefore, NLR may be considered as a novel surrogate marker of DN in early stages.

Keywords: Diabetic nephropathy, inflammation, microvascular, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, urine albumin

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is a systemic disease having serious microvascular and macrovascular complications. Microvascular complications include diabetic nephropathy (DN), diabetic retinopathy, and diabetic neuropathy while macrovascular complications include stroke, cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), and peripheral vascular diseases.[1]

DN is a common micro-angiopathic complication in patients with diabetes. DN is one of the most common causes of end-stage renal disease (ESRD).[2] DN is clinically manifested as increased albumin urea excretion starting from microalbuminuria to macroalbuminuria and eventually ESRD.[3] However, the degree of albuminuria is not necessarily linked to disease progression in patients with DN associated with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).[4,5] In type 1 diabetes, once overt DN develops, there is persistent proteinuria, and progression toward ESRD could only be slowed but could not be stopped.[6,7] Due to this, there is a need of early predictors of DN by which we can predict the disease and can halt the progression of the disease. The Asian Indian population has more prevalence of DN as compared to the Caucasian population.[8]

Several studies that have explored the relationship between systemic inflammation and vascular disease indicated that chronic inflammation promotes the development and acceleration of micro- and macro-angiopathic complications in patients with diabetes. Total white blood cell (TWBC) count is a crude but sensitive indicator of inflammation which can be done easily in laboratory routinely. It is a cost-effective investigation. Increase in the neutrophil count is seen in thrombus formation and ischemic diseases. The neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) in complete blood count is studied in many cardiac and noncardiac diseases as an inflammatory marker and is used to predict the prognosis of diseases such as acute myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and heart failure.[9,10]

DN in T2DM has an inflammatory pathology. Many inflammatory markers have been found to be related to DN, such as interleukin-1 (IL1), IL6, IL8, transforming growth factor beta 1, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and cytokines. However, their measurement is not used routinely as it is not easy to do it.[11,12] In this respect, NLR has emerged as a novel surrogate marker.

In the present study, the association of NLR with DN in Indian patients is studied, whether or not NLR can be used as a surrogate marker of DN in this population.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

An observational cross-sectional study was done from March 2015 to March 2016 in patients referred to the endocrine outpatient department. All diagnosed T2DM patients were included in this study. Patients with type 1 DM; patients with infections, for example, urinary tract infection (UTI), upper respiratory tract infection, lower respiratory tract infections, gastrointestinal infection, otitis media, viral hepatitis, pyrexia of unknown origin, parasitic infection, viral infection, tuberculosis, local infection, skin infection, AIDS; patients with systemic disorder such as CVD, chronic kidney disease (CKD), chronic liver disease, blood disorders, autoimmune disorders, malignancy, poisoning; patients on anti-inflammatory drugs, systemic or topical steroids, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, alcohol; patients with uncontrolled blood pressure (BP); patients having diseases affecting urinary protein excretion as nephritic syndrome, urolithiasis, renal insufficiency, renal artery stenosis, dehydration state, and UTI; and patients having low glomerular filtration rate (GFR) without microalbuminuria were excluded from the study.

Diagnosed T2DM patients were screened. Information about duration of DM, treatment history, age, sex, smoking, alcohol intake history, family history, and other chronic illness was collected. Complete physical examination was done including height, weight, waist to hip ratio (WHR), body mass index (BMI), pulse rate, BP, cyanosis, clubbing, pallor, icterus, jugular venous pressure, acanthosis, and other abnormal signs were noted such as dehydration and pyrexia.

Routine blood investigations such as complete blood picture, liver function tests (LFTs), kidney function tests, urine routine microscopy, urine microscopy, lipid profile, fasting blood sugar (FBS)/postprandial blood sugar (PPBS), chest X-ray, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and ultrasonography of the abdomen with kidney size were done. Fundus examination was done to assess diabetic retinopathy; nerve conduction velocity of all limbs was done to assess for diabetic neuropathy.

Albuminuria was tested by MICRAL-II TEST strips by dipstick method. Urinary albumin excretion (UAE) of 20–200 mg/L was assessed as microalbuminuria. It is a semi-quantitative method of urine albumin analysis. Test was repeated within 3 months of interval.

Evaluation of DN was done by examining urine for albuminuria. According to the American Diabetes Association and Mogensen DN diagnostic criteria, DM patients with UAE ratio reaching 20 mcg/min to 200 mcg/min or 30 mg/day to 300 mg/day are considered to have early stage of DN.[13,14,15] GFR was calculated using CKD-Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula. SPSS statistical software (SPSS for Windows, version 20.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical calculation. Ethical approval for this study was provided by the Instructional Ethics Committee, Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal.

RESULTS

In this study, diagnosed T2DM patients were screened for DN.

A total of 115 diabetic patients were registered. Of these, 56 patients had DN and 59 had normal urine albumin. All these patients were similar in their age distribution, dietary habits, smoking and alcohol consumption, and other profiles. These groups were compared for various variables such as age, BMI, WHR, BP, total leukocyte count, absolute neutrophil count (ANC), absolute lymphocyte count (ALC), NLR, serum creatinine, blood urea, serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase (SGPT), serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT), FBS, PPBS level, total cholesterol, triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), very LDL (VLDL), and HbA1c.

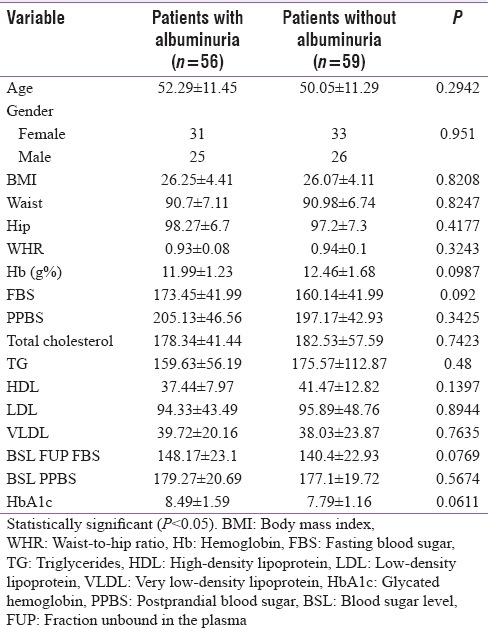

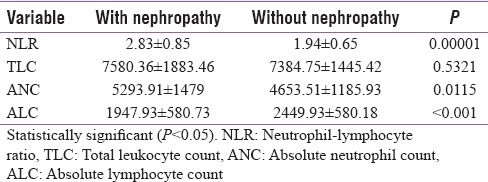

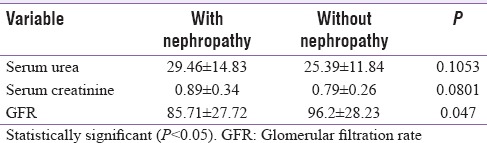

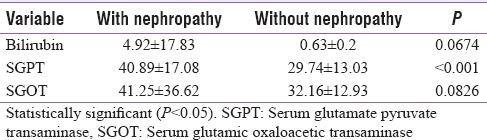

In the present study, the mean age of patients of normal group and DN group was 52.29 ± 11.45 years and 50.05 ± 11.29 years, respectively. Both groups had similar distribution of age (P = 0.294). In addition, there was no sex-related variability (in normal group, male = 26, female = 33, and in DN group, male = 25, female = 31) (P = 0.951). Metabolic and laboratory parameters such as BMI, lipid profile (total cholesterol, TG, HDL, LDL) and glycemic parameters (blood sugar level [BSL] fraction unbound in the plasma FBS, BSL PPBS, HbA1c) were compared in both groups and are shown in Table 1. There was a significant difference between the normal group and DN group with relation to NLR (P < 0.001), but individually, the TWBC count did not differ in the two groups [Table 2]. There was also a significant difference between normal group and DN group with relation to ANC (P < 0.001) and ALC (P < 0.001) [Table 2]. In the present study, renal function tests of all patients were carried out, and estimated GFR (eGFR) was calculated by CKD-EPI formulae. In relation to eGFR, there was a significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.047) [Table 3]. Patients with albuminuria had a significantly low eGFR (mean eGFR = 85.71 ± 27.72) than the normal group (mean eGFR = 96.2 ± 28.23). However, other investigations such as blood urea and serum creatinine had no difference in these two groups [Table 3]. LFTs for all patients were carried out, and SGPT (mean SGPT = 40.89 ± 36.62) was found to be significantly raised in DN patients' group as compared to normal patients' group (mean SGPT = 9.74 ± 13.03), which was highly statistically significant (P < 0.001) [Table 4]. In reference to glycemic parameters, we did not observe any significant difference with respect to FBS (P = 0.0769), PPBS (P = 0.5674), and HbA1c (P = 0.06) in the two groups, i.e., normal diabetic patients and patients with DN. In our study, by applying linear regression analysis, we found HBA1c as a risk factor for DN.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic and laboratory parameters of diabetic patients

Table 2.

Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and other laboratory parameters of diabetic patients

Table 3.

Renal function test of diabetic patients

Table 4.

Liver function test of diabetic patients

DISCUSSION

The key finding of this study was that NLR levels were found to be significantly associated (P = 0.001) with patients who were diagnosed with early-stage DN as compared to those with normal albumin levels. This study is one of the first in India to assess the relationship between NLR and DN.

Over the past decade, multiple studies have shed light on the role and importance of inflammatory molecules (such as adipokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, and cytokines) and endothelial dysfunction in the development of insulin resistance, diabetes, and its various complications.[16,17,18,19,20,21] The exact pathogenesis of DN is unknown. However, a cascade of pathological events (with glomerular damage being an early sign, which gives rise to proteinuria, followed by progressive renal damage, fibrosis, inflammation, and finally loss of functional nephrons) is known to play an important role in the development and progression of DN.[21,22,23,24,25] Renal inflammation in the setting of DN is known to play a critical role.[21] WBC count and its subtypes are among the readily available and inexpensive classic inflammatory markers.[26] Multiple studies have established that inflammatory markers such as neutrophilia and relative lymphocytopenia are independent markers of many diseases, especially complications of DM, such as DN.[10,11,12,20,21,27] However, establishing a diagnosis individually based on WBC, neutrophil, or lymphocyte counts has its own biases, unlike NLR, which is a dynamic parameter that has a higher prognostic value.[11,12,28]

NLR is a novel marker of chronic inflammation that exhibits a balance of two interdependent components of the immune system; neutrophils that are the active nonspecific inflammatory mediator forms the first line of defense whereas lymphocytes are the regulatory or protective component of inflammation.[29] Interestingly, NLR has been found to have a positive relation with not only the presence but also the severity of metabolic syndrome.[30] A study by Imtiaz et al.[31] has suggested that chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes have a significant association with systemic inflammation, reflected by NLR. Shiny et al.[32] have shown that NLR is correlated with increasing severity of glucose intolerance and insulin resistance and can be used as a prognostic marker for macro- and micro-vascular complications in patients with glucose intolerance. Initially, NLR was recognized as a predictive marker in multiple types of cancer that might assist in patient stratification and individual risk assessment.[33,33,35] But recently, multiple other studies have indicated that NLR might be a predictive marker for vascular diseases also. Tsai et al.[36] had shown that NLR correlated strongly with the risk of ischemic CVDs. Other studies have shown NLR to be an independent predictor of major adverse cardiac events in patients with MI,[37] and NLR was also associated with poor survival rates after coronary artery bypass grafting.[12]

Recently, several studies have suggested that NLR could play a predictive role for assessing the development of microvascular complications of diabetes. In a study, Ulu et al.[38] demonstrated NLR to be a quick and reliable prognostic marker for diabetic retinopathy and its severity. Another recent study by Ulu et al.[27] concluded that NLR can be considered as a predictive and prognostic marker for sensorineural hearing loss in diabetic patients. A study conducted in geriatric population also suggested that increased NLR levels were in itself an independent predictor for microvascular complications of DM.[39]

In CKD patients, NLR has shown to be an easy and inexpensive laboratory parameter that provides significant information regarding inflammation.[40] Moreover, in a 3-year follow-up study of diabetic patients, NLR served as a predictor of worsening renal function.[41] Afsar has shown that NLR could be related to DN and is also correlated as an indicator of ESRD.[42] In another study, Akbas et al.[43] have shown that NLR was significantly elevated in patients with increased albuminuria pointing toward a relationship between inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in diabetics with nephropathy.

Similarly in our study, the mean NLR among diabetic patients with albuminuria (2.83 ± 0.85) was significantly higher than among those without albuminuria (1.94 ± 0.65). In addition, ANC and ALC levels were also found to be significantly correlated with patients with albuminuria. In concordance with our results, Huang et al.[44] have also found that NLR values were significantly higher in diabetic patients with evidence of nephropathy (2.48 ± 0.59) than in diabetic patients without nephropathy (2.20 ± 0.62) and healthy controls (1.80 ± 0.64). ANC and ALC levels were also found to correlate with DN in their study. Moreover, a recent study in Egyptian patients has shown that NLR values were significantly higher in diabetic patients with retinopathy (P < 0.001), neuropathy (P = 0.025), and nephropathy (P < 0.001) than those of diabetic patients without any microvascular complications and healthy controls.[45] Another recently published study in Turkish patients has also shown that NLR levels significantly increased in parallel to albuminuria levels in diabetic patients.[46]

There was no significant correlation between normal and DN groups in relation to age, sex, BMI, WHR, Hb, total cholesterol, LDL, TG, HDL, and VLDL as observed in the present study although there was significant difference among the two groups in respect to eGFR values (P = 0.047). Patients with albuminuria had significantly low eGFR (mean eGFR = 85.71 ± 27.72) as compared to those patients with normal albumin levels (mean eGFR = 96.2 ± 28.23). eGFR is one of the most specific parameters for kidney function.[47] In case of DN, eGFR decreases as disease progresses. There were no significant intergroup differences for either blood urea or serum creatinine levels.

Among the LFTs, SGPT (mean SGPT = 40.89 ± 36.62) was significantly raised in patients with albuminuria as compared to patients without DN (mean SGPT = 9.74 ± 13.03) (P = 0.0001). In T2DM, there is loss of direct effect of insulin to suppress hepatic glucose production and glycogenolysis in the liver. This in turn causes an increase in hepatic glucose production. In T2DM, hyperinsulinemia in combination with high free fatty acids and hyperglycemia is known to upregulate lipogenic transcription factors. The fatty acids overload the hepatic mitochondrial oxidation system, leading to accumulation of fatty acids in the liver. These mechanisms finally lead to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in T2DM patients. In the majority of cases, NAFLD causes asymptomatic abnormality of liver enzyme levels which include SGPT, SGOT, and ALP. Of these liver enzymes, SGPT is most closely related to liver fat accumulation and consequently SGPT has been used as a marker of NAFLD. Other studies have also identified that hyperglycemia may lead to oxidative stress and glycation reactions resulting in advanced glycation end products. Oxidative stress is also one of the factors which alter liver enzymes (SGPT, SGOT, and ALP).[48]

In reference to glycemic parameters, there were no significant differences between the two groups, in relation to FBS, PPBS, or HbA1c though other studies have shown HbA1c to be an independent risk factor for DN.[44,46] On applying linear regression analysis in the present study, HbA1c was also found to be a predictor for DN.

One of the limitations of this study is that this was a cross-sectional analysis and the sample size was relatively small. Since this was not a prospective controlled study, any conclusive causal associations between NLR and DN could not be investigated.

CONCLUSION

The results of our study have shown that there was a significant correlation between NLR and DN, implying that inflammation and endothelial dysfunction could be an integral part of DN. NLR was significantly and independently raised in patients with type 2 DM having increased albuminuria. Therefore, NLR may be considered as a predictor and a prognostic risk marker of DN. NLR is an easy to calculate parameter in the laboratory by observing the differential leukocyte count. This test is simple, inexpensive, and done routinely. In a setup with limited laboratory facilities, NLR is a simple test which can be an alternative for other costlier inflammatory markers such as ILs, TNF, cytokines, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. Further research with a prospective design and multiple NLR measurements will shed more light on the role of NLR as a marker of inflammation and a probable risk factor for DN.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rathmann W, Giani G. Global prevalence of diabetes: Estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2568–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ritz E, Rychlík I, Locatelli F, Halimi S. End-stage renal failure in type 2 diabetes: A medical catastrophe of worldwide dimensions. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;34:795–808. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(99)70035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chronic Kidney Disease Surveillance System. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 19]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/ckd . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans T, Capell P. Diabetic Nephropathy. [Last accessed 2017 Mar 21]. Available from: http://journal.diabetes.org/clinicaldiabetes/v18n12000/Pg7.htm .

- 5.Perkins BA, Ficociello LH, Roshan B, Warram JH, Krolewski AS. In patients with type 1 diabetes and new-onset microalbuminuria the development of advanced chronic kidney disease may not require progression to proteinuria. Kidney Int. 2010;77:57–64. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caramori ML, Fioretto P, Mauer M. Low glomerular filtration rate in normoalbuminuric type 1 diabetic patients: An indicator of more advanced glomerular lesions. Diabetes. 2003;52:1036–40. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.4.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mogensen CE. Long-term antihypertensive treatment inhibiting progression of diabetic nephropathy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;285:685–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6343.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parving HH, Andersen AR, Smidt UM, Svendsen PA. Early aggressive antihypertensive treatment reduces rate of decline in kidney function in diabetic nephropathy. Lancet. 1983;1:1175–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92462-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brancati FL, Whittle JC, Whelton PK, Seidler AJ, Klag MJ. The excess incidence of diabetic end-stage renal disease among blacks. A population-based study of potential explanatory factors. JAMA. 1992;268:3079–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudiger A, Burckhardt OA, Harpes P, Müller SA, Follath F. The relative lymphocyte count on hospital admission is a risk factor for long-term mortality in patients with acute heart failure. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:451–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Núñez J, Núñez E, Bodí V, Sanchis J, Miñana G, Mainar L, et al. Usefulness of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in predicting long-term mortality in ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:747–52. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson PH, Croal BL, Cuthbertson BH, Small GR, Ifezulike AI, Gibson G, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and outcome from coronary artery bypass grafting. Am Heart J. 2007;154:995–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.KDIGO. Chapter 1: Definition and classification of CKD. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 19];Kidney Int Suppl. 2013 3:19. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2012.64. Available from: http://www.kdigo.org/clinicalpractice_guidelines/pdf/CKD/KDIGO_2012_CKD_GL.pdf . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gross JL, de Azevedo MJ, Silveiro SP, Canani LH, Caramori ML, Zelmanovitz T. Diabetic nephropathy: Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:164–76. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruggenenti P, Remuzzi G. Nephropathy of type-2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:2157–69. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V9112157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldberg RB. Cytokine and cytokine-like inflammation markers, endothelial dysfunction, and imbalanced coagulation in development of diabetes and its complications. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3171–82. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujita T, Hemmi S, Kajiwara M, Yabuki M, Fuke Y, Satomura A, et al. Complement-mediated chronic inflammation is associated with diabetic microvascular complication. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2013;29:220–6. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rivero A, Mora C, Muros M, García J, Herrera H, Navarro-González JF. Pathogenic perspectives for the role of inflammation in diabetic nephropathy. Clin Sci (Lond) 2009;116:479–92. doi: 10.1042/CS20080394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Astrup AS, Tarnow L, Pietraszek L, Schalkwijk CG, Stehouwer CD, Parving HH, et al. Markers of endothelial dysfunction and inflammation in type 1 diabetic patients with or without diabetic nephropathy followed for 10 years: Association with mortality and decline of glomerular filtration rate. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1170–6. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pitsavos C, Tampourlou M, Panagiotakos DB, Skoumas Y, Chrysohoou C, Nomikos T, et al. Association between low-grade systemic inflammation and type 2 diabetes mellitus among men and women from the ATTICA study. Rev Diabet Stud. 2007;4:98–104. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2007.4.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim AK, Tesch GH. Inflammation in diabetic nephropathy. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:146154. doi: 10.1155/2012/146154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Retnakaran R, Cull CA, Thorne KI, Adler AI, Holman RR. UKPDS Study Group. Risk factors for renal dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study 74. Diabetes. 2006;55:1832–9. doi: 10.2337/db05-1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garg JP, Bakris GL. Microalbuminuria: Marker of vascular dysfunction, risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Vasc Med. 2002;7:35–43. doi: 10.1191/1358863x02vm412ra. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McIntyre NJ, Taal MW. How to measure proteinuria? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2008;17:600–3. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328313675c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gai M, Motta D, Giunti S, Fop F, Masini S, Mezza E, et al. Comparison between 24-h proteinuria, urinary protein/creatinine ratio and dipstick test in patients with nephropathy: Patterns of proteinuria in dipstick-negative patients. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2006;66:299–307. doi: 10.1080/00365510600608563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torun S, Tunc BD, Suvak B, Yildiz H, Tas A, Sayilir A, et al. Assessment of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in ulcerative colitis: A promising marker in predicting disease severity. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36:491–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ulu S, Bucak A, Ulu MS, Ahsen A, Duran A, Yucedag F, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a new predictive and prognostic factor at the hearing loss of diabetic patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271:2681–6. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2734-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azab B, Jaglall N, Atallah JP, Lamet A, Raja-Surya V, Farah B, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of adverse outcomes of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2011;11:445–52. doi: 10.1159/000331494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhutta H, Agha R, Wong J, Tang TY, Wilson YG, Walsh SR. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts medium-term survival following elective major vascular surgery: A cross-sectional study. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2011;45:227–31. doi: 10.1177/1538574410396590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buyukkaya E, Karakas MF, Karakas E, Akçay AB, Tanboga IH, Kurt M, et al. Correlation of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio with the presence and severity of metabolic syndrome. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2014;20:159–63. doi: 10.1177/1076029612459675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imtiaz F, Shafique K, Mirza SS, Ayoob Z, Vart P, Rao S. Neutrophil lymphocyte ratio as a measure of systemic inflammation in prevalent chronic diseases in Asian population. Int Arch Med. 2012;5:2. doi: 10.1186/1755-7682-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shiny A, Bibin YS, Shanthirani CS, Regin BS, Anjana RM, Balasubramanyam M, et al. Association of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio with glucose intolerance: An indicator of systemic inflammation in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2014;16:524–30. doi: 10.1089/dia.2013.0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jung MR, Park YK, Jeong O, Seon JW, Ryu SY, Kim DY, et al. Elevated preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts poor survival following resection in late stage gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:504–10. doi: 10.1002/jso.21986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee YY, Choi CH, Kim HJ, Kim TJ, Lee JW, Lee JH, et al. Pretreatment neutrophil: Lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in cervical carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:1555–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mallappa S, Sinha A, Gupta S, Chadwick SJ. Preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio >5 is a prognostic factor for recurrent colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:323–8. doi: 10.1111/codi.12008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsai JC, Sheu SH, Chiu HC, Chung FM, Chang DM, Chen MP, et al. Association of peripheral total and differential leukocyte counts with metabolic syndrome and risk of ischemic cardiovascular diseases in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2007;23:111–8. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akpek M, Kaya MG, Lam YY, Sahin O, Elcik D, Celik T, et al. Relation of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio to coronary flow to in-hospital major adverse cardiac events in patients with ST-elevated myocardial infarction undergoing primary coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:621–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ulu SM, Dogan M, Ahsen A, Altug A, Demir K, Acartürk G, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a quick and reliable predictive marker to diagnose the severity of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2013;15:942–7. doi: 10.1089/dia.2013.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Öztürk ZA, Kuyumcu ME, Yesil Y, Savas E, Yildiz H, Kepekçi Y, et al. Is there a link between neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and microvascular complications in geriatric diabetic patients? J Endocrinol Invest. 2013;36:593–9. doi: 10.3275/8894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okyay GU, Inal S, Oneç K, Er RE, Pasaoglu O, Pasaoglu H, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in evaluation of inflammation in patients with chronic kidney disease. Ren Fail. 2013;35:29–36. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2012.734429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Azab B, Daoud J, Naeem FB, Nasr R, Ross J, Ghimire P, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of worsening renal function in diabetic patients (3-year follow-up study) Ren Fail. 2012;34:571–6. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2012.668741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Afsar B. The relationship between neutrophil lymphocyte ratio with urinary protein and albumin excretion in newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Med Sci. 2014;347:217–20. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31828365cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Akbas EM, Demirtas L, Ozcicek A, Timuroglu A, Bakirci EM, Hamur H, et al. Association of epicardial adipose tissue, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio with diabetic nephropathy. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:1794–801. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang W, Huang J, Liu Q, Lin F, He Z, Zeng Z, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio is a reliable predictive marker for early-stage diabetic nephropathy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2015;82:229–33. doi: 10.1111/cen.12576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moursy EY, Megallaa MH, Mouftah RF, Ahmed SM. Relationship between neutrophil lymphocyte ratio and microvascular complications in Egyptian patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Intern Med. 2015;3:250–5. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kahraman C, Kahraman NK, Aras B, Cosgun S, Gülcan E. The relationship between neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and albuminuria in type 2 diabetic patients: A pilot study. Arch Med Sci. 2016;12:571–5. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.59931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levey AS, Inker LA, Matsushita K, Greene T, Willis K, Lewis E, et al. GFR decline as an end point for clinical trials in CKD: A scientific workshop sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation and the Us Food and Drug Administration. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64:821–35. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alkhouri N, Morris-Stiff G, Campbell C, Lopez R, Tamimi TA, Yerian L, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio: A new marker for predicting steatohepatitis and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2012;32:297–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]