Abstract

This study explores the relative contribution of parental and teacher support to adolescents’ psychosomatic health complaints, with a particular focus on gender and age differences. Based on a survey of 49,172 ninth‐ and eleventh‐grade students in Stockholm (2006–2014), structural equation modeling results demonstrated negative associations between parental and teacher support on psychosomatic health complaints. Parental support had a stronger association with the outcome among girls than boys. It was also more important than teacher support for psychosomatic health complaints. Parental support was more important for younger girls’ health compared to older girls, with opposite patterns for teacher support. These findings highlight the need to consider gender and age to understand the links between social support and health during adolescence.

Over several decades, the importance of supportive relationships in individual's well‐being and longevity has been recognized as an empirical regularity in the field of public health science, leading to general theory formation regarding social support and health (Berkman, Glass, Brissette, & Seeman, 2000; Cohen & Syme, 1985). While primarily originating from studies on adults, these theories have been successfully applied to the adolescent population as well (Colarossi & Eccles, 2003; Furman & Buhrmester, 1992; Kristjánsson & Sigfúsdóttir, 2009). During adolescence, parents and teachers constitute two important sources of social support. Parents are usually the primary providers of emotional (e.g., love and caring) support, while the role of teachers is more oriented toward lending instrumental (tangible and material) support (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985; Malecki & Demaray, 2003). Past research has repeatedly shown that support from parents and teachers is fundamental for adolescent health and well‐being (Brolin Låftman & Östberg, 2006; Cornwell, 2003; Khatib, Bhui, & Stansfeld, 2013; Meehan, Durlak, & Bryant, 1993; Stewart & Suldo, 2011; Thapa, Cohen, Guffey, & Higgins‐D'Alessandro, 2013). With regard to parental support, previous studies have found links to symptoms of psychopathology and life satisfaction (Stewart & Suldo, 2011), psychological and depressive symptoms (Barber, Stolz, & Olsen, 2005; Khatib et al., 2013), and psychosomatic complaints (Brolin Låftman & Östberg, 2006) among adolescents. Concerning teachers as a source of social support, studies suggest that they are important not only for adolescents’ academic success and functioning (Suldo et al., 2009) but also for their self‐esteem (Eccles & Roeser, 2011) and mental well‐being (Thapa et al., 2013). In addition, at least a few studies have investigated the mutual contribution of parental and teacher support to adolescent well‐being, finding that while these two types of support are correlated, they are still independently linked to young people's well‐being (Chong, Huan, Yeo, & Ang, 2006; Walsh, Harel‐Fisch, & Fogel‐Grinvald, 2010).

In general, however, studies on social support and adolescent health have not sufficiently addressed the fact that adolescence is a multifaceted phase in life, nor that adolescents represent a rather heterogeneous group. Adolescence is characterized by growth and change, as manifested in individuals’ striving for increased autonomy from the adult world, particularly from their parents. The importance of parental support tends to decrease over age, whereas support from friends becomes more important; this shift seems to take place between the ages of 12 and 17 for boys and 12 and 14 for girls (Helsen, Vollebergh, & Meeus, 2000). Although poor parental support is linked to a higher level of emotional problems throughout adolescence, this association appears to be particularly strong among younger adolescents (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992). Similarly, supportive relationships with teachers tend to be more important for younger adolescents’ emotional status than to older ones. A possible explanation of these findings could be the transition from compulsory to upper secondary school, where it is more common to have specialist subject teachers rather than one or two class mentors. This might in turn reduce the likelihood of forming close relationships with teachers (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992). It may thus be expected that the importance of parents and perhaps also of teachers as sources of social support is less pronounced in the late stages of adolescence. In addition to age, it is reasonable to expect gender differences in the associations between social support and health. To begin with, girls report more psychosomatic health complaints compared to boys, and this gender gap increases over age (Hauglund, Wold, Stevenson, Aaroe, & Woynarowska, 2001; Kinnunen, Laukkanen, & Kylma, 2010). Gender differences have also been found in how adolescents perceive support from their parents and teachers, with girls reporting stronger connectedness to their parents and more support from both teachers and parents than boys (Kristjánsson & Sigfúsdóttir, 2009; Reddy, Rhodes, & Mulhall, 2003; Rueger, Chen, Jenkins, & Choe, 2014). However, this may differ depending on the type of support that is considered: girls report higher levels of emotional support from teachers, whereas boys perceive higher levels of instrumental and appraisal support in the classroom (Brolin Låftman & Modin, 2012). Considering the reasoning above, the health implications of parental and teacher support may thus differ according to gender. In line with this notion are the findings of previous studies, showing that support from mothers (Rueger et al., 2014) and teachers have a stronger effect on girls’ depressive symptoms, while support from fathers is more strongly associated with depressive symptoms among boys (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992).

In sum, past research investigating the importance of parental and teacher support in adolescent health has usually not paid sufficient attention to gender or age as important stratifying dimensions. Of the studies that do exist, most are based on small‐scale data sources. Through structural equation modeling (SEM) of a representative sample of nearly 50,000 adolescents living in Stockholm, Sweden, this study aims to first investigate the relative importance of support provided by parents and teachers in psychosomatic health complaints. Second, it aims to examine whether there are any gender and age differences in these associations.

Methods

Data Source

The Stockholm School Survey is a cross‐sectional study targeting all ninth‐grade (age 15) and eleventh‐grade (age 17) students in the municipality of Stockholm. It is carried out by the Stockholm City Administration every second year as part of their preventive work against drugs and delinquency and covers all public and most private schools in the municipality. External attrition (i.e., students who do not take part in the survey due to absence from school when the survey took place) and internal attrition due to unreliably completed questionnaires have been estimated to equal 22% by the Stockholm Office of Research and Statistics (Brolin Låftman & Modin, 2012). The current study was based on students who participated in the waves conducted in 2006 (n = 9,947), 2008 (n = 10,910), 2010 (n = 11, 515), 2012 (n = 9,270), and 2014 (7,530). All students participated voluntarily, and the questions were answered anonymously. The survey does not include personal information that enables identification. Studies using the data are exempt from obtaining ethical approval by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (no. 2010/241‐31/5).

Variables

Two independent variables were examined, each of which was based on five items: parental support (praise from parents, encourage, notice, care, and example) and teacher support (praise from teacher, decision, school tell parents, bullying, and help). Higher scores reflect higher levels of support. For these items, the reference category was set to the “worst off” category (i.e., reflecting the least support). The dependent variable was psychosomatic health complaints as measured by 10 items (headache, depressed, frightened, not good enough, slept uneasily, sluggish/uneasy, appetite, change yourself, nervous tummy, and falling asleep), which reflect the individual's experience of various psychological and somatic problems. Higher scores correspond to more frequent or more severe complaints. For each item, the “best off” category (i.e., reflecting the least complaints) was chosen as the reference category. Descriptions of all items, along with the original phrasing of the questions and Cronbach's alpha coefficients, can be seen in Table 1. The items were constructed for the Stockholm School Survey, without any references to the literature. Therefore, we further assessed the unidimensionality of the latent factors through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The following statistics were derived: the root‐mean‐square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI). Values around or below .06 for the RMSEA and close to .95 for the CFI and TLI are generally considered indicators of an acceptable model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). All three latent factors were shown to have satisfactory fit (psychosomatic health complaints: RMSEA = .057, CFI = .957, TLI = .968; parental support: RMSEA = .091, CFI = .935, TLI = .956; teacher support: RMSEA = .036, CFI = .976, TLI = .984).

Table 1.

Outline of the Study Variables: Original Questions and Response Options. Alpha Values From Reliability Analyses (n = 49,172)

| Latent Factors | Items | Original Questions/Statements | Response Options | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental support | Praise from parents | They praise me when I do something good |

|

|

| Boys age 15, α = .80 | Encourage | They usually encourage and support me | ||

| Girls age 15, α = .82 | Notice | My parents notice if I do something good | ||

| Boys age 17, α = .82 | Care | I care about what my parents say | ||

| Girls age 17, α = .84 | Example | My parents are an example to me | ||

| Teacher support | Praise from teachers | Teachers praise students who do something good at school |

|

|

| Boys age 15, α = .72 | Decision | Students take part in making decisions on things that are important to us | ||

| Girls age 15, α = .70 | School tell parents | The school lets my parents know if I've done something good | ||

| Boys age 17, α = .70 | Bullying | Adults step in if anyone is harassed and bullied | ||

| Girls age 17, α = .69 | Help | If you don't understand something, you get help from the teacher straight away | ||

| Psychosomatic health complaints | Headachea | How often have you had headache this school year? |

(a) (b) (c) |

|

| Boys age 15, α = .78 | Depressedb | Do you feel sad and depressed without knowing why? | ||

| Girls age 15, α = .82 | Frightenedb | Do you ever feel frightened without knowing why? | ||

| Boys age 17, α = .79 | Not good enoughb | How often do you feel you are not good enough? | ||

| Girls age 17, α = .81 | Slept uneasilya | How often this school year have you slept uneasily and woken up during the night? | ||

| Sluggish/uneasyb | Do you feel sluggish and uneasy? | |||

| Appetitea | How often have you had a bad appetite? | |||

| Change yourselfc | How much would you like to change yourself? | |||

| Nervous tummya | How often this year have you had “nervous tummy?” | |||

| Falling asleepa | How often this school year have you had difficulties falling asleep? | |||

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was restricted to participants who had complete information on all variables included in the analyses (n = 49,172), corresponding to 77% of the students who participated in the study. In the first step, descriptive statistics of the study variables were derived, with independent sample t‐tests of the mean differences by gender and age.

The associations were analyzed through SEM using Mplus version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998), which enabled the variables to be treated as categorical indicators. The structural equation model first included three latent factors representing parental support, teacher support, and psychosomatic health complaints, producing factor loadings for each item. Secondly, the correlation between parental support and teacher support as well as their respective associations with psychosomatic health complaints were added to the model. Year of data collection was added as a control variable. To examine the differences in these associations across gender and age, a group variable consisting of four categories (boys age 15, girls age 15, boys age 17, and girls age 17) was used. The final model showed the following fit values: RMSEA = .049, CFI = .945 and TLI = .950.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics of the study variables are presented in Table 2. With regard to parental support, the mean levels for boys are significantly lower than those of girls for all included items. Gender differences in the mean levels of teacher support are small overall, although girls report significantly lower levels for some of the items, particularly “praise” and “help.” An interesting finding is that boys in both age groups report less praise from their parents compared to girls, while the reverse is true concerning praise from teachers. Compared to girls, boys in both age groups report that they receive more help from teachers. Moreover, as expected, both 15‐year‐old and 17‐year‐old girls report significantly more psychosomatic health complaints than boys. The comparison between 15‐ and 17‐year‐olds shows no consistent age patterns for parental support or for teacher support. However, it should be noted that both boys and girls in the older age group report to a higher extent than those in the younger age group that they care about what their parents say and that their parents are an example for them. The older adolescents also feel more included in making decisions on things that are important to them in school but report less communication between the school and their parents. Finally, the older boys and girls report more psychosomatic health complaints compared to the younger ones (the only exception being headache among boys and poor appetite and wanting to change oneself among girls).

Table 2.

Descriptions of the Study Variables by Gender and Age (n = 49,172). Comparisons Are Based on Independent Samples t‐Tests

| % The “Worst Off” Response Option | Range | Boys Age 15 (n = 11,327) | Girls Age 15 (n = 11,883) | Boys Age 17 (n = 11,659) | Girls Age 17 (n = 14,346) | Comparison Boys–Girls Age 15c | Comparison Boys–Girls Age 17c | Comparison Age 15–17 Boysd | Comparison Age 15–17 Girlsd | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean diff.g | Mean diff.g | Mean diff.g | Mean diff.g | |||

| Parental supporta | ||||||||||||||

| Praise from parents | 2.5 | 1–4 | 3.51 | .73 | 3.55 | .69 | 3.49 | .73 | 3.56 | .69 | −.05 | −.07 | .02 | −.00 |

| Encourage | 2.7 | 1–4 | 3.43 | .76 | 3.47 | .75 | 3.42 | .74 | 3.52 | .74 | −.04 | −.09 | .01 | −.04 |

| Notice | 3.1 | 1–4 | 3.24 | .77 | 3.25 | .78 | 3.20 | .76 | 3.26 | .77 | −.01 | −.06 | .04 | −.01 |

| Care | 5.2 | 1–4 | 3.17 | .88 | 3.23 | .83 | 3.23 | .83 | 3.35 | .78 | −.06 | −.12 | −.06 | −.13 |

| Example | 8.6 | 1–4 | 2.90 | .96 | 2.93 | .95 | 3.00 | .93 | 3.13 | .90 | −.04 | −.13 | −.11 | −.20 |

| Teacher supporta | ||||||||||||||

| Praise from teacher | 5.2 | 1–4 | 2.90 | .81 | 2.87 | .78 | 2.92 | .78 | 2.86 | .78 | .03 | .06 | −.02 | .01 |

| Decision | 9.9 | 1–4 | 2.50 | .87 | 2.53 | .82 | 2.63 | .82 | 2.70 | .78 | −.03 | −.07 | −.13 | −.16 |

| School tell parents | 42.7 | 1–4 | 1.99 | 1.00 | 1.98 | .96 | 1.87 | .94 | 1.80 | .89 | .02 | .07 | .13 | .18 |

| Bullying | 7.5 | 1–4 | 2.86 | .89 | 2.84 | .86 | 2.86 | .85 | 2.88 | .82 | .02 | −.02 | −.00 | −0.4 |

| Help | 8.8 | 1–4 | 2.74 | .87 | 2.66 | .85 | 2.76 | .84 | 2.69 | .83 | .08 | .07 | −.02 | −.03 |

| % The “Best off” Response Option | Range |

Boys Age 15 (n = 11 327) |

Girls Age 15 (n = 11 883) |

Boys Age 17 (n = 11 659) |

Girls Age 17 (n = 14 346) |

Comparison Boys–Girls Age 15e |

Comparison Boys–Girls Age 17e |

Comparison Age 15–17 Boysf |

Comparison Age 15–17 Girlsf |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean diff.g | Mean diff.g | Mean diff.g | Mean diff.g | |||

| Psychosomatic health complaintsb | ||||||||||||||

| Headache | 14.1 | 1–5 | 2.55 | 1.16 | 3.13 | 1.15 | 2.48 | 1.14 | 3.17 | 1.13 | −.58 | −.69 | .07 | −.04 |

| Depressed | 27.2 | 1–5 | 2.08 | 1.20 | 3.00 | 1.26 | 2.16 | 1.22 | 3.05 | 1.23 | −.92 | −.89 | −.08 | −.05 |

| Frightened | 70.7 | 1–5 | 1.30 | .73 | 1.66 | .97 | 1.28 | .71 | 1.66 | .98 | −.36 | −.38 | .02 | .00 |

| Not good enough | 13.8 | 1–5 | 1.76 | 1.07 | 2.47 | 1.25 | 1.80 | 1.07 | 2.47 | 1.23 | −.71 | −.67 | −0.4 | .00 |

| Slept uneasily | 30.8 | 1–5 | 1.99 | 1.11 | 2.55 | 1.20 | 2.08 | 1.15 | 2.73 | 1.22 | −.56 | −.65 | −.09 | −.17 |

| Sluggish/uneasy | 28.0 | 1–5 | 2.18 | 1.18 | 2.54 | 1.17 | 2.33 | 1.16 | 2.69 | 1.15 | −.36 | −.36 | −.16 | −.15 |

| Appetite | 40.2 | 1–5 | 2.06 | 1.32 | 2.66 | 1.41 | 2.04 | 1.31 | 2.58 | 1.37 | −.60 | −.55 | .01 | .07 |

| Change yourself | 41.4 | 1–5 | 2.41 | 1.11 | 3.02 | 1.19 | 2.45 | 1.09 | 2.95 | 1.14 | −.61 | −.62 | −.04 | .07 |

| Nervous tummy | 25.5 | 1–5 | 2.22 | 1.19 | 2.74 | 1.26 | 2.26 | 1.21 | 2.88 | 1.27 | −.52 | −.12 | −.04 | −.14 |

| Falling asleep | 16.8 | 1–5 | 2.88 | 1.40 | 3.32 | 1.32 | 3.00 | 1.39 | 3.37 | 1.30 | −.44 | −.38 | −.11 | −.05 |

Higher values indicate more parental and teacher support.

Higher values indicate more psychosomatic health complaints.

A negative difference value in parental and teacher support reflects that girls report more support compared to boys.

A negative difference value in parental and teacher support reflects that 17‐year‐olds report more support compared to 15‐year‐olds.

A negative difference value in psychosomatic health complaints reflects that girls report poorer health compared to boys.

A negative difference value in psychosomatic health complaints reflects that 17‐year‐olds report poorer health compared to 15‐year‐olds.

Bold estimates reflect statistically significant differences (p < .05).

Relative Importance of Parental and Teacher Support for Psychosomatic Health Complaints

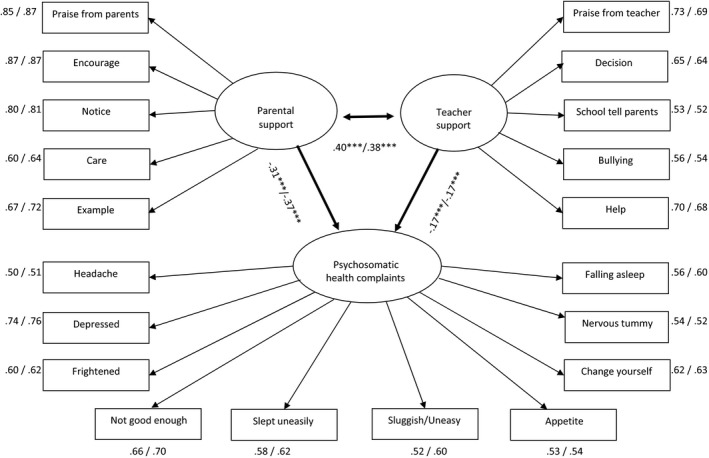

Figure 1 shows the results of the SEM for the 15‐year‐old boys and girls. The items representing the latent variable parental support show factor loadings from .60–.87 for boys and .64–.87 for girls. The factor loadings on items for teacher support range between .53 and .73 for boys and .52 and .69 for girls. Regarding psychosomatic health complaints, the factor loadings are .50–.74 for boys and .51–.76 for girls. The correlation between parental support and teacher support is of moderate strength in both boys (r = .40, p < .001) and girls (r = .38, p < .001). Furthermore, the results show a negative association between parental support and psychosomatic health complaints in boys (B = −.31, p < .001) and girls (B = −.37, p < .001), suggesting that those who report higher levels of parental support have fewer complaints. The results for teacher support and psychosomatic health complaints also show a negative association in boys (B = −.17, p < .001) and girls (B = −.17, p < .001).

Figure 1.

Structural equation model of parental support, teacher support, and psychosomatic health complaints among 15‐year‐old boys and girls (n = 23,166). Estimates (standardized) are displayed as males/females. Adjusted for year of data collection. ***p < .001; ** p < .01; *p < .05.

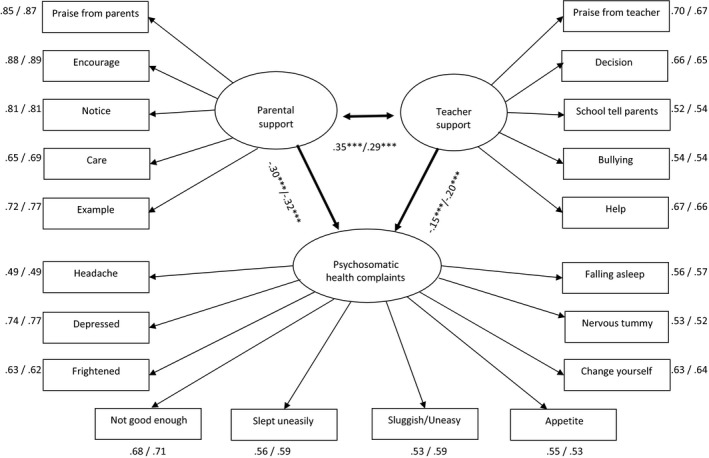

Figure 2 demonstrates the corresponding results for the 17‐year‐olds. The factor loadings for parental support range from .65 to .88 for boys and .69 to .89 for girls and for teacher support between .52 and .70 for boys and .54 and .67 for girls. Concerning psychosomatic health complaints, the factor loadings range from .49 to .74 for boys and .49 to .77 for girls. The results of the structural components show similar results for the 17‐year‐olds as for the 15‐year‐olds. Thus, the correlation between parental support and teacher support is of moderate strength here as well (boys: r = .35, p < .001; girls: r = .29, p < .001). A negative association between parental support and psychosomatic health complaints exists in both genders (boys: B = −.30, p < .001; girls: B = −.32, p < .001). Similar results as those of the 15‐year‐olds are also found for the association between teacher support and psychosomatic health complaints (boys: B = −.15, p < .001; girls B = −.20).

Figure 2.

Structural equation model of parental support, teacher support, and psychosomatic health complaints among 17‐year‐old boys and girls (n = 26,006). Estimates (standardized) are displayed as males/females. Adjusted for year of data collection. ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05.

Gender and Age Differences

Postestimation procedures based on Wald tests were conducted to assess which of the model parameters significantly (p < .05) differed across gender and age. The results show that parental support is more strongly related to psychosomatic health complaints than teacher support. This remained true for boys regardless of age and for the 15‐year‐old girls, but not for the 17‐year‐old girls. Parental support seems to be more important to girls’ psychosomatic health complaints than to the health of the boys, which holds for both age groups. No such gender differences are found in teacher support and health among the 15‐year‐olds. Moreover, support from parents is more important to the 15‐year‐old girls’ reporting of psychosomatic health complaints compared to that of the 17‐year‐old girls, whereas the opposite pattern is found for teacher support.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the contribution of parental support on the one hand and teacher support on the other to adolescents’ psychosomatic health complaints. The study further examined whether there were any gender and age differences in the studied associations.

In line with much previous research (Brolin Låftman & Östberg, 2006; Cornwell, 2003; Khatib et al., 2013; Meehan et al., 1993; Stewart & Suldo, 2011), a negative association was found between parental support and psychosomatic health complaints in both genders. Similarly, a negative association was found between teacher support and psychosomatic health complaints in both boys and girls. Studies in the same area of research have demonstrated contradictory findings; several studies have shown that indicators of social support from teachers are related to adolescents’ mental health (Gustafsson et al., 2010; Thapa et al., 2013), at least one study failed to identify any such association (Ellonen, Kääriäinen, & Autio, 2008).

With the exception of 17‐year‐old girls, parental support was a significantly stronger predictor than teacher support of psychosomatic health complaints in this sample of adolescents. This finding is not surprising; although many adolescents spend more of their time at school than at home, their relationships with their parents are more important. Most likely, parental and teacher support serve different purposes in an adolescent's life. This has also been suggested by Furman and Buhrmester (1985), who found that parents usually provide emotional support, while teachers lend more instrumental support. That said, it should be emphasized that the associations between teacher support and health in the current study were robust even when accounting for parental support. Thus, support from teachers seems to be beneficial to the psychosomatic health complaints of boys and girls regardless of the support that these young people receive from home.

The results indicated that, for both age groups, parental support was more important to girls’ psychosomatic health complaints than those of boys. This is in line with previous research claiming that girls are more closely connected to and receive more support from their parents (Kristjánsson & Sigfúsdóttir, 2009). The results further pointed to parental support as being more important for younger girls’ health than that of older girls, whereas the opposite pattern was found for teacher support. A possible explanation for this may be that as children grow older support from their parents decreases in importance at the same time as they become more reliant on support from their friends and romantic partners, especially among girls (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992). In other words, girls’ transition from their last year of compulsory school (age 15) to upper secondary school (age 17) may reflect a significant change in the types of relationships that most contribute to their health and well‐being.

Finally, our results showed that among 17‐year‐olds, teacher support was a stronger predictor of girls’ psychosomatic health complaints than those of boys. This finding may suggest that the pursuit of good grades, especially evident in upper secondary school, is likely to play an important role in students’ stress levels and health during this stage in life—a situation in which teachers are probably best suited to provide stress‐reducing support. Girls are, in general, more performance‐oriented than boys, and previous research has found that the association between school performance and health complaints has a greater bearing on girls’ well‐being than that of boys (Brolin Låftman & Modin, 2012). Consequently, a possible reason for the relatively stronger impact of teacher support on girls’ health could be that girls’ focus on performance may make them more sensitive to the support provided by teachers situated in the performance‐based context.

Strengths and Limitations

The study was based on a total sample of ninth‐ and eleventh‐grade students in Stockholm, which is a clear strength of the present study. The use of SEM enabled the study to fully capitalize on the advantage of the comprehensive data on parental support, teacher support, and psychosomatic health complaints. Additionally, the SEM framework enabled us to examine age and gender differences within the same statistical model.

As previously stated, the internal attrition was calculated to be 23%. However, an attrition analysis showed that there were only marginal differences between the total sample and the study sample regarding the distribution of parental support, teacher support, and psychosomatic health complaints (data not presented).

The generalizability of the study is limited to adolescents attending schools in Stockholm County. Another limitation is the cross‐sectional study design, which means that assumptions of causality cannot be made. However, the assumed direction of the correlation studied here has a strong justification based on several other studies in the field (Brolin Låftman & Östberg, 2006; Meehan et al., 1993; Stewart & Suldo, 2011). With regard to the measures, they were all self‐reported and thus may have been vulnerable to recall bias and negative affectivity bias. Moreover, the measures of the main independent variables (parental support and teacher support) have not been previously analyzed based on the Stockholm School Survey. The measures of parental support and teacher support may not reflect their exact definition and could therefore have insufficient construct validity. Although the alpha coefficients and model fit statistics from CFA were deemed acceptable for both parental support and teacher support in the current study, it would have been desirable to use validated instruments to measure these concepts. Furthermore, one should be aware of other factors that could explain the associations found here, such as aspects related to school performance and social background. However, a sensitivity analysis (data not shown) controlling for school grades and parental education did not significantly change the main results of the study. It could nevertheless be the case that these types of factors play an important role in how the associations between support and health among young people develop over time.

Conclusions

The results of the current study suggest that gender and age should be emphasized in future research on the associations between social support and health during adolescence. Comparing the results of boys and girls and of younger and older students may provide important insight into the mechanisms linking support to health. This study has also revealed the necessity of considering different types of support—for example, parental and teacher support—simultaneously. While parental support was generally more important for psychosomatic health complaints, there were also robust and independent statistical effects of teacher support on psychosomatic health complaints. In other words, adolescents seem to benefit health‐wise from high levels of teacher support regardless of the levels of support they receive from their parents. Accordingly, teachers have the potential to play a key role in the improvement of adolescents’ health and well‐being. Providing students with a supportive environment at school may be one way of counteracting the high—and seemingly increasing—levels of psychosomatic health complaints that are observed in Sweden and many other countries in the Western world today.

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare and The Swedish Research Council (Forte: 2013‐00159; VR: 2014‐10107). We would also like to thank the Stockholm City Social Development Unit for granting us access to the data, which made the study possible.

References

- Barber, K. B. , Stolz, E. H. , & Olsen, A. J. (2005). Parental support, psychological control, and behavioral control: Assessing relevance across time, culture, and method. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 70, 1–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman, L. F. , Glass, T. , Brissette, I. , & Seeman, T. E. (2000). From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science and Medicine, 51, 843–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brolin Låftman, S. , & Modin, B. (2012). School‐performance indicators and subjective health complaints: Are there gender differences? Sociology of Health and Illness, 34, 608–625. doi:10.1111/j.1467‐9566.2011.01395.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brolin Låftman, S. , & Östberg, V. (2006). The pros and cons of social relations: An analysis of adolescents’ health complaints. Social Science and Medicine, 63, 611–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong, W. H. , Huan, V. S. , Yeo, L. S. , & Ang, R. P. (2006). Asian adolescents’ perceptions of parent, peer, and school support and psychological adjustment: The mediating role of dispositional optimism. Current Psychology, 25, 212–228. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. , & Syme, S. L. (1985). Social support and health. Orlando, FL: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colarossi, L. G. , & Eccles, J. S. (2003). Differential effects of support providers on adolescents’ mental health. Social Work Research, 27, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell, B. (2003). The dynamic properties of social support: Decay, growth, and staticity, and their effects on adolescent depression. Social Forces, 81, 953–978. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J. S. , & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 225–241. doi:10.1111/j.1532‐7795.2010.00725.x [Google Scholar]

- Ellonen, N. , Kääriäinen, J. , & Autio, V. (2008). Adolescent depression and school social support: A multilevel analysis of a Finnish sample. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 552–567. doi:10.1002/jcop.20254 [Google Scholar]

- Furman, W. , & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Children's perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology, 21, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Furman, W. , & Buhrmester, D. (1992). Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development, 63, 103–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, J.‐E. , Allodi Westling, M. , Alin Åkerman, B. , Eriksson, C. , Eriksson, L. , Fischbein, S. , … Persson, R. (2010). School, learning and mental health. A systematic review. Stockholm, Sweden: Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien. [The Royal Swedish Academy of Science]. [Google Scholar]

- Hauglund, S. , Wold, B. , Stevenson, J. , Aaroe, L. E. , & Woynarowska, B. (2001). Subjective health complaints in adolescence. A cross‐national comparison of prevalence and dimensionality. European Journal of Public Health, 11, 4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsen, M. , Vollebergh, W. , & Meeus, W. (2000). Social support from parents and friends and emotional problems in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29, 319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. T. , & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling – A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118 [Google Scholar]

- Khatib, Y. , Bhui, K. , & Stansfeld, S. A. (2013). Does social support protect against depression & psychological distress? Findings from the RELACHS study of East London adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 393–402. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnunen, P. , Laukkanen, E. , & Kylma, J. (2010). Associations between psychosomatic symptoms in adolescence and mental health symptoms in early adulthood. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 16, 43–50. doi:10.1111/j.1440‐172X.2009.01782.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristjánsson, Á. L. , & Sigfúsdóttir, I. D. (2009). The role of parental support, parental monitoring, and time spent with parents in adolescent academic achievement in Iceland: A structural model of gender differences. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 53, 481–496. doi:10.1080/00313830903180786 [Google Scholar]

- Malecki, C. K. , & Demaray, M. K. (2003). What type of support do they need? Investigating student adjustment as related to emotional, informational, appraisal, and instrumental support. School Psychology Quarterly, 18, 231–252. doi:10.1521/scpq.18.3.231.22576 [Google Scholar]

- Meehan, M. P. , Durlak, J. A. , & Bryant, F. B. (1993). The relationship of social support to perceived control and subjective mental‐health in adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology, 21, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K. , & Muthén, B. O. (1998. –2015). Mplus user's guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, R. , Rhodes, J. E. , & Mulhall, P. (2003). The influence of teacher support on student adjustment in the middle school years: A latent growth curve study. Development & Psychopathology, 15, 119–138. doi:10.1017/.S0954579403000075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueger, S. Y. , Chen, P. , Jenkins, L. N. , & Choe, H. J. (2014). Effects of perceived support from mothers, fathers, and teachers on depressive symptoms during the transition to middle school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 655–670. doi:10.1007/s10964‐013‐0039‐x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, T. , & Suldo, S. (2011). Relationships between social support sources and early adolescents’ mental health: The moderating effect of student achievement level. Psychology in the Schools, 48, 1016–1033. doi:10.1002/pits.20607 [Google Scholar]

- Suldo, M. S. , Friedrich, A. A. , White, T. , Farmer, J. , Minch, D. , & Michalowski, J. (2009). Teacher support and adolescents’ subjective well‐being: A mix‐methods investigation. School Psychology Review, 38, 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, A. , Cohen, J. , Guffey, S. , & Higgins‐D'Alessandro, A. (2013). A review of school climate research. Review of Educational Research, 83, 357–385. doi:10.3102/0034654313483907 [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, S. D. , Harel‐Fisch, Y. , & Fogel‐Grinvald, H. (2010). Parents, teachers and peer relations as predictors of risk behaviors and mental well‐being among immigrant and Israeli born adolescents. Social Science & Medicine, 70, 976–984. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]