Abstract

Objective

To assess the efficacy and safety of subcutaneous (SC) belimumab in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Methods

Patients with moderate‐to‐severe SLE (score of ≥8 on the Safety of Estrogens in Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment [SELENA] version of the SLE Disease Activity Index [SLEDAI]) were randomized 2:1 to receive weekly SC belimumab 200 mg or placebo by prefilled syringe in addition to standard SLE therapy for 52 weeks. The primary end point was the SLE Responder Index (SRI4) at week 52. Secondary end points were reduction in the corticosteroid dosage and time to severe flare. Safety was assessed according to the adverse events (AEs) reported and the laboratory test results.

Results

Of 839 patients randomized, 836 (556 in the belimumab group and 280 in the placebo group) received treatment. A total of 159 patients withdrew before the end of the study. At entry, mean SELENA–SLEDAI scores were 10.5 in the belimumab group and 10.3 in the placebo group. More patients who received belimumab were SRI4 responders than those who received placebo (61.4% versus 48.4%; odds ratio [OR] 1.68 [95% confidence interval (95% CI) 1.25–2.25]; P = 0.0006). In the belimumab group, both time to and risk of severe flare were improved (median 171.0 days versus 118.0 days; hazard ratio 0.51 [95% CI 0.35–0.74]; P = 0.0004), and more patients were able to reduce their corticosteroid dosage by ≥25% (to ≤7.5 mg/day) during weeks 40–52 (18.2% versus 11.9%; OR 1.65 [95% CI 0.95–2.84]; P = 0.0732), compared with placebo. AE incidence was comparable between treatment groups; serious AEs were reported by 10.8% of patients taking belimumab and 15.7% of those taking placebo. A worsening of IgG hypoglobulinemia by ≥2 grades occurred in 0.9% of patients taking belimumab and 1.4% of those taking placebo.

Conclusion

In patients with moderate‐to‐severe SLE, weekly SC doses of belimumab 200 mg plus standard SLE therapy significantly improved their SRI4 response, decreased severe disease flares as compared with placebo, and had a safety profile similar to placebo plus standard SLE therapy.

B lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS), also known as B cell–activating factor, is a potent B cell survival and differentiation factor 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Its overexpression drives systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)–like disease in mice 6, 7, 8. BLyS is also associated with SLE in humans 9, 10, 11 and correlates with disease activity 12, 13. Pharmacologic neutralization or genetic elimination of BLyS successfully treats and/or prevents murine SLE 6, 14, 15.

Intravenous (IV) administration of belimumab, a recombinant human monoclonal antibody that binds to and inhibits the biologic activity of BLyS 16, was shown in 2 large, multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trials in patients with SLE (the Study of Belimumab in Subjects with SLE 52‐week trial [BLISS‐52] and the BLISS 76‐week trial [BLISS‐76]) to be safe and efficacious at a dose of 10 mg/kg in combination with standard SLE therapy 17, 18. IV administration of belimumab was subsequently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of patients with active, autoantibody‐positive SLE who are receiving standard SLE therapy, including corticosteroids, antimalarials, immunosuppressants, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs 19, 20.

The approval of a drug for SLE was a breakthrough; however, the IV route of administration poses challenges for some patients. Patients must visit a clinic or infusion center every 2 weeks for the first 3 doses and then every 4 weeks thereafter 21, thereby incurring substantial costs in time for travel to/from the drug‐administering site, time for the infusion itself, and time for postinfusion monitoring. In addition, substantial financial expenses related to clinic personnel and supplies are incurred.

The ability to administer subcutaneous (SC) belimumab away from the clinic would largely eliminate these costs and thereby enhance treatment options for patients with SLE. Indeed, more patients chose SC treatment over IV treatment in a study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, with a decreased need to travel to receive an infusion being an influential factor 22.

A liquid formulation of belimumab has been developed, along with a prefilled syringe and an autoinjector device for administering belimumab SC. In a single‐dose study, healthy volunteers self‐administered belimumab 200 mg SC using the prefilled syringe or the autoinjector device; both injection devices demonstrated good usability, reliability, and safety 23. The 200 mg SC dose was selected in order to achieve a target belimumab steady‐state area under the curve exposure following SC administration similar to that obtained with 10 mg/kg IV every 4 weeks 24, 25.

The objectives of the present study were to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of belimumab SC administered via prefilled syringe in patients with active, autoantibody‐positive SLE. Our findings are presented below.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design and patient population

This was a 52‐week randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study (BLISS‐SC ID BEL112341; ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT01484496) carried out at 177 sites in 30 countries in North, Central, and South America, Eastern and Western Europe, Australia, and Asia between November 2011 and February 2015. All study patients provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. The study and all protocols were institutional review board–approved and were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, 2008 26.

Patients ≥18 years of age were required to have a diagnosis of SLE according to the American College of Rheumatology criteria 27, with antinuclear antibodies and/or anti–double‐stranded DNA (anti‐dsDNA) antibodies and a score of ≥8 on the Safety of Estrogens in Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment (SELENA) version of the SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) at screening (range 0–105) 28. Those with severe lupus kidney disease (proteinuria >6 gm/24 hours or equivalent according to a spot urinary protein‐to‐creatinine ratio or a serum creatinine level >2.5 mg/dl) or severe central nervous system (CNS) lupus were excluded.

Patients were randomized 2:1 to receive weekly doses of belimumab 200 mg or placebo administered SC with a prefilled syringe in addition to stable doses of standard SLE therapy. No loading dose was used. Randomization was stratified by a screening SELENA–SLEDAI score (≤9 versus ≥10), complement level (those with versus those without low C3 and/or C4), and race (black versus non‐black). Patients must have received a stable SLE medication regimen for at least 30 days prior to enrollment. Background SLE medications were restricted, such that patients who received a protocol‐prohibited medication or a dosage that exceeded the protocol‐defined limits were deemed to have failed treatment and were analyzed as nonresponders from the date of treatment failure through week 52. The first and second SC doses of study drug were carried out at the study site under supervision; at the investigator's discretion, patients or caregivers could then administer subsequent doses at home. The injection site was rotated weekly between the abdomen and the thigh. Patients recorded in a logbook the date, injection site, and amount of dose administered.

End points and assessments

The primary end point was the SLE Responder Index (SRI4) response rate at week 52 29. The SRI4 is a composite index requiring a ≥4‐point reduction in the SELENA–SLEDAI score, no worsening (increase of <0.3 from baseline) in the physician's global assessment (on a 0–10‐cm visual analog scale), and no new British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG) A organ domain score or 2 new BILAG B organ domain scores at week 52 compared with baseline. On sensitivity analyses, the primary end point at week 52 was also repeated for the completer and per‐protocol populations.

The end points that supported the primary end point included the SRI4 by visit, SRI4 components by visit, and the SRI5–8 by visit. The definition of SRI5–8 was the same as that of SRI4, except with increasingly higher thresholds for SELENA–SLEDAI score reduction of 5–8 points. The time to first SRI4 that was maintained through week 52 was also assessed. The SRI4 response and change from baseline in SELENA–SLEDAI score, excluding the anti‐dsDNA and complement components, were analyzed post hoc.

Key secondary end points were time to first severe flare (as measured by the SLE flare index, modified to exclude the single criterion of increased SELENA–SLEDAI score to >12) 30, 31, 32 and reduction in corticosteroid dosage (percentage of patients among those receiving >7.5 mg/day at baseline who experienced a mean dosage reduction of ≥25% from baseline to ≤7.5 mg/day during weeks 40–52).

Other prespecified corticosteroid use end points included the percentage of patients with any increase in corticosteroid use, the percentage of patients whose dosage was reduced from >7.5 mg/day at baseline to ≤7.5 mg/day, and cumulative corticosteroid dose.

The SRI4 was analyzed across subgroups, including the baseline SELENA–SLEDAI score (≤9 and ≥10), race (black and non‐black), baseline corticosteroid use (receiving and not receiving corticosteroids), and body weight quartiles (<55.05 kg, ≥55.05 kg to <65.15 kg, ≥65.15 kg to <78.25 kg, and ≥78.25 kg). Subgroup analyses were also completed post hoc for Hispanic or Latino patients. Mean change from baseline in the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue (FACIT‐Fatigue) score (range 0–52) 33 and the percentage of patients with an improvement in the FACIT‐Fatigue score of ≥4 (minimal clinically important difference) were analyzed by visit (weeks 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 52).

The time to first renal flare over 52 weeks was analyzed among patients with baseline proteinuria >0.5 gm/24 hours. Renal flare was defined as the reproducible development (i.e., confirmed at the subsequent clinical visit) of 1 or more of the following 3 features: 1) an increase in 24‐hour urinary protein to >1,000 mg if baseline was <200 mg or to >2,000 mg if baseline was 200–1,000 mg or to more than twice a baseline value of >1,000 mg; 2) a decrease in the glomerular filtration rate of >20%, accompanied by proteinuria (>1,000 mg/24 hours), hematuria (≥4 red blood cells [RBCs]/high‐power field [hpf]), and/or cellular (RBC and white blood cell) casts; and 3) new hematuria (≥11–20 RBCs/hpf) or a 2‐grade increase in hematuria compared with baseline, associated with >25% dysmorphic RBCs, glomerular in origin, and accompanied by an 800‐mg increase in 24‐hour urinary protein level or new RBC casts 34.

Safety was evaluated by adverse event (AE) reporting, laboratory parameters, and immunogenicity testing. AEs were coded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities system organ class and preferred term. A serious AE (SAE) was defined as an AE that resulted in any of the following outcomes: death, was life‐threatening (i.e., an immediate threat to life), inpatient hospitalization, prolongation of an existing hospitalization, persistent or significant disability/incapacity, congenital anomaly/birth defect, or was medically important (i.e., required treatment to prevent one of the medical outcomes above).

Blood samples for pharmacokinetic analyses were obtained from all randomized patients before the injection at weeks 0, 4, 8, 16, 24, and 52 and at the 8‐week follow‐up visit.

Statistical analysis

A sample size of 816 (544 taking belimumab and 272 taking placebo) was calculated to provide at least 90% power at a P = 0.05 significance level, assuming the true treatment difference was 12% improvement (belimumab versus placebo) at week 52; the treatment difference was based on the response in the phase III belimumab IV studies 17, 18. The intent‐to‐treat (ITT) population was defined as all patients who were randomized and received at least 1 dose of study medication. A completer population (patients who completed 52 weeks of treatment) and a per‐protocol population (patients in the ITT who did not have a major protocol deviation) were included in the sensitivity analyses. The pharmacokinetic population included all patients who received at least 1 dose of study medication and who contributed at least 1 post‐belimumab pharmacokinetic sample.

A step‐down sequential testing procedure was used for the primary and 2 key secondary end points to control the overall Type I error rate (the incorrect rejection of a true null hypothesis). The prespecified sequence for assessing statistical significance (2‐sided α = 0.05) was as follows: 1) SRI4 response rate at 52 weeks; 2) time to first severe SLE flare; and 3) percentage of patients with a reduction in corticosteroid dosage. End points in this sequence could only be interpreted as being statistically significant if statistical significance was achieved by all prior tests. The proportion of patients with an SRI4 response at week 52 was compared between treatment groups using a logistic regression model. Analyses of other efficacy end points (all 2‐sided with a significance level of 0.05) were not subjected to a multiple comparison procedure. Patients who withdrew or were deemed to have failed treatment were analyzed as nonresponders in the primary analysis.

RESULTS

Patient population

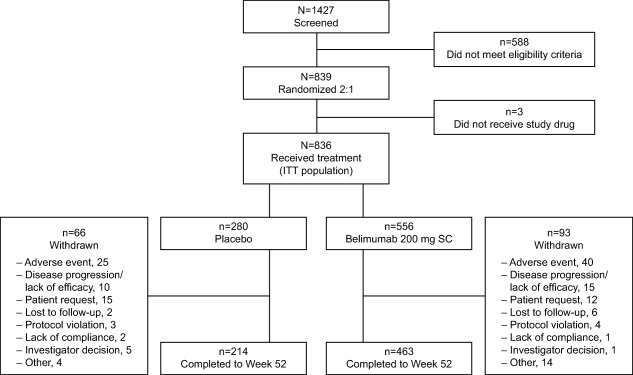

There were 836 patients in the ITT population, and 159 withdrew overall. The most common reasons for withdrawal were AEs, patient request, and disease progression/lack of efficacy (Figure 1). The majority of patients were female (93.7% receiving belimumab, 95.7% receiving placebo), with a mean age of 38.6 years (38.1 years in the belimumab group, 39.6 years in the placebo group) and a mean/median baseline SELENA–SLEDAI score of 10.4/10.0 (10.5/10.0 in the belimumab group, 10.3/10.0 in the placebo group) (Table 1). The majority of patients received corticosteroids at baseline (86.5% belimumab, 86.1% placebo), and approximately one‐third of patients received corticosteroids in combination with antimalarials. Almost half of the patients received immunosuppressants (43.9% belimumab, 48.9% placebo), with azathioprine being the one most commonly received (Table 1). The mean ± SD self‐reported compliance with the SC injections was 96.4 ± 9.37% for belimumab and 96.4 ± 9.75% for placebo.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the disposition of the study patients from initial screening to the end of week 52. ITT = intent‐to‐treat; SC = subcutaneous.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study patients at baseline, by treatment groupa

|

Placebo (n = 280) |

Belimumab 200 mg SC (n = 556) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Female, no. (%) | 268 (95.7) | 521 (93.7) |

| Age, mean ± SD years | 39.6 ± 12.61 | 38.1 ± 12.10 |

| Weight, mean ± SD kg | 69.5 ± 19.76 | 68.6 ± 18.15 |

| Enrollment by region, no. (%) | ||

| US | 84 (30.0) | 153 (27.5) |

| Americas, excluding US | 57 (20.4) | 115 (20.7) |

| Western Europe/Australia/Israel | 19 (6.8) | 48 (8.6) |

| Eastern Europe | 59 (21.1) | 129 (23.2) |

| Asia | 61 (21.8) | 111 (20.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 80 (28.6) | 160 (28.8) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 200 (71.4) | 396 (71.2) |

| Disease duration, median (range) years | 4.6 (0–38) | 4.3 (0–35) |

| SELENA–SLEDAI (range 0–105)b | ||

| Mean ± SD | 10.3 ± 3.04 | 10.5 ± 3.19 |

| Median (range) | 10.0 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 | 10.0 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 |

| Score of ≤9, no. (%) | 112 (40.0) | 204 (36.7) |

| Score of ≥10, no. (%) | 168 (60.0) | 352 (63.3) |

| Organ system involvement, no. (%) | ||

| Mucocutaneous | 248 (88.6) | 487 (87.6) |

| Musculoskeletal | 218 (77.9) | 438 (78.8) |

| Immunologic | 210 (75.0) | 423 (76.1) |

| Renal | 41 (14.6) | 58 (10.4) |

| Hematologic | 23 (8.2) | 40 (7.2) |

| Vascular | 18 (6.4) | 46 (8.3) |

| Cardiovascular and respiratory | 18 (6.4) | 29 (5.2) |

| Constitutional | 3 (1.1) | 7 (1.3) |

| Central nervous system | 2 (0.7) | 7 (1.3) |

| Disease flare, no. (%)c | ||

| At least 1 flare | 57 (20.4) | 92 (16.5) |

| At least 1 severe flare | 4 (1.4) | 8 (1.4) |

|

Physician's global assessment, mean ± SD (0–10‐cm VAS) |

1.5 ± 0.45 | 1.6 ± 0.43 |

| FACIT‐Fatigue, mean ± SD (range 0–52) | 32.1 ± 11.35 | 31.9 ± 12.17 |

| Medications, no. (%) | ||

| Corticosteroids only | 31 (11.1) | 59 (10.6) |

| Immunosuppressants only | 7 (2.5) | 10 (1.8) |

| Antimalarials only | 16 (5.7) | 44 (7.9) |

| Corticosteroids and immunosuppressants only | 50 (17.9) | 88 (15.8) |

| Corticosteroids and antimalarials only | 93 (33.2) | 201 (36.2) |

| Immunosuppressants and antimalarials only | 13 (4.6) | 13 (2.3) |

| Corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and antimalarials | 67 (23.9) | 133 (23.9) |

| Immunosuppressants | ||

| Azathioprine | 58 (20.7) | 107 (19.2) |

| Methotrexate | 39 (13.9) | 52 (9.4) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 34 (12.1) | 70 (12.6) |

SC = subcutaneous; VAS = visual analog scale; FACIT‐Fatigue = Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue subscale.

Patients had a score of ≥8 on the Safety of Estrogens in Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment version of the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SELENA–SLEDAI) at screening (occurring within 35 days prior to baseline). A total of 39 belimumab‐treated patients and 24 placebo‐treated patients had scores that were <8 at baseline (lowest score was 2).

Occurring during the screening period (day −35 to day 0).

SRI4 response

At week 52, 61.4% of belimumab patients were SRI4 responders compared with 48.4% for placebo (odds ratio [OR] 1.68 [95% confidence interval (95% CI) 1.25–2.25]; P = 0.0006) (Figure 2A). The SRI4 response was significantly greater in the belimumab group as compared with the placebo group as early as week 16, and the significant difference was sustained up to week 52 (Figure 2A). At week 52, more patients who received belimumab were SRI4 responders compared with placebo in both the completer population (n = 677) (72.9% versus 63.1%; OR 1.54 [95% CI 1.07–2.20]; P = 0.0185) and the per‐protocol population (n = 789) (61.9% versus 48.3%; OR 1.75 [95% CI 1.29–2.37]; P = 0.0003).

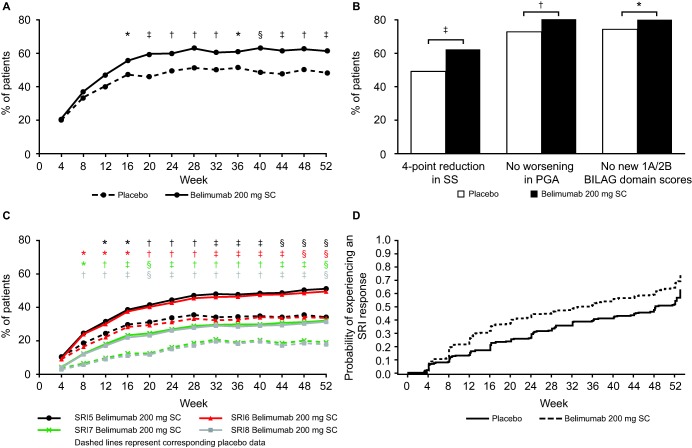

Figure 2.

A, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Responder Index (SRI4) responses over time in patients randomized to receive placebo or belimumab 200 mg subcutaneously (SC). B, Percentage of patients with responses on the individual components of the SRI4 at week 52: the Safety of Estrogens in Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment version of the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SS), the physician's global assessment (PGA), and the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG) domain, by treatment group. C, SRI5, 6, 7, and 8 responses over time in the 2 treatment groups. D, Time to first SRI4 response that was maintained through week 52 in the intent‐to‐treat population, by treatment group. ∗ = P ≤ 0.05; † = P ≤ 0.01; ‡ = P ≤ 0.001; § = P ≤ 0.0001.

All components of the SRI4 showed statistical significance at week 52 (Figure 2B). The immunologic, musculoskeletal, mucocutaneous, and vascular SELENA–SLEDAI organ systems improved significantly more in the belimumab group than in the placebo group at week 52 (data not shown). Improvement in the other organ systems (including renal) favored belimumab numerically, but the analyses in these other organ systems were limited by small sample sizes. Among patients with a BILAG A or B organ domain score at baseline, a significantly greater improvement was observed at week 52 in the belimumab group compared with the placebo group for the vasculitis, mucocutaneous, and musculoskeletal organ domains, but not the other organ domains.

Compared with the placebo group, the SRI5 response was significantly greater in the belimumab group from week 12 through week 52 (Figure 2C). The SRI6, SRI7, and SRI8 responses were significantly greater from week 8 through week 52 (P ≤ 0.0001 for each comparison at week 52). The median time to first SRI4 response that was maintained through week 52 was 235.0 days (interquartile range [IQR] 85.0–not calculable) for belimumab and 338.0 days (IQR 141.0–386.0) for placebo (hazard ratio [HR] 1.48 [95% CI 1.21–1.81]; P = 0.0001) (Figure 2D).

When the anti‐dsDNA and complement components of the SELENA–SLEDAI were excluded from the composite score (post hoc analysis), the SRI4 response rate was significantly greater in the belimumab group as compared with placebo (59.6% versus 48.0%; OR 1.58 [95% CI 1.18–2.13]; P = 0.0023). The least squares mean ± SEM change from baseline in the SELENA–SLEDAI score (excluding anti‐dsDNA and complement components) at week 52 was not significantly different between treatment groups (−3.96 ± 0.246 for belimumab, −3.47 ± 0.295 for placebo; P = 0.0997).

Time to severe flare

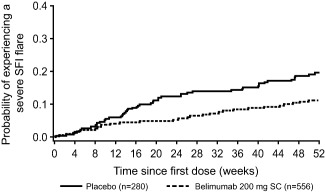

Patients who received belimumab were 49% less likely to experience severe flare as compared with placebo across the 52 weeks of study (HR 0.51 [95% CI 0.35–0.74]; P = 0.0004). Among patients experiencing a severe flare, the median time to severe flare was 171.0 days (IQR 57.0–257.0) for belimumab (n = 59 [10.6%]) versus 118.0 days (IQR 62.0–259.0) for placebo (n = 51 [18.2%]) (Figure 3). The risk of any flare was also significantly lower in the belimumab group compared with placebo (60.6% versus 68.6%; HR 0.78 [95% CI 0.65–0.93]; P = 0.0061).

Figure 3.

Time to severe flare in patients randomized to receive placebo or belimumab 200 mg subcutaneously (SC). The probability of experiencing a severe flare, according to the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Flair Index (SFI), is plotted against the time since the first dose of study drug.

Changes in corticosteroid dosage

At baseline, 335 patients in the belimumab group and 168 in the placebo group were receiving corticosteroids at a dosage of >7.5 mg/day (60.2% of patients overall) and were eligible for this analysis. More patients who received belimumab were able to reduce their corticosteroid dosage by ≥25%, to ≤7.5 mg/day, during weeks 40–52 as compared with placebo (18.2% versus 11.9%), although this difference did not achieve statistical significance (OR 1.65 [95% CI 0.95–2.84]; P = 0.0732). Fewer patients in the belimumab group (8.1% [45 of 556]) than in the placebo group (13.2% [37 of 280]) had an increase in corticosteroid dosage through to week 52 (OR 0.55 [95% CI 0.34–0.87]; P = 0.0117); the differences were significant from week 20 to week 52, with the exception of week 32. The proportion of patients who had a corticosteroid dosage reduction from >7.5 mg/day at baseline to ≤7.5 mg/day at week 52 was 20.0% (67 of 335) in the belimumab group and 14.3% (24 of 168) in the placebo group (P = 0.1181). There was a difference of 633.50 mg in the mean ± SD cumulative dose of corticosteroids over 52 weeks (3,933.8 ± 3,660.76 for belimumab and 4,567.3 ± 5,981.53 for placebo; P = 0.4299).

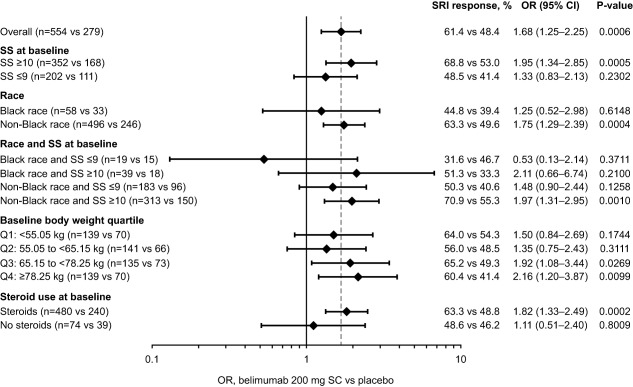

Subgroup responses at week 52

Results of the subgroup analyses are summarized in Figure 4, which includes the number of patients in each subgroup. At week 52, significantly more patients with baseline SELENA–SLEDAI scores of ≥10 who received belimumab were SRI4 responders compared with those who received placebo. There was a trend toward an increase in SRI4 responders for belimumab versus placebo among patients with baseline SELENA–SLEDAI scores of ≤9, although this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Responder Index (SRI4) subgroup responses at week 52 in patients randomized to receive belimumab 200 mg subcutaneously (SC) versus placebo. Bars illustrate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) that are given at the right. Broken vertical line indicates the overall OR. SRI = Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Responder index; SS = the Safety of Estrogens in Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment version of the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index.

The SRI4 response among non‐black patients who received belimumab was statistically significantly higher than that among non‐black patients who received placebo (OR 1.75 [95% CI 1.29–2.39]; P = 0.0004) (Figure 4). Among the black patients, the week 52 SRI4 response was numerically higher for belimumab than for placebo, but the difference did not achieve statistical significance. Post hoc analyses showed that 73.8% (118 of 160) of Hispanic or Latino patients receiving belimumab experienced an SRI4 response at week 52, compared with 50.0% (40 of 80) of those receiving placebo (P = 0.0003). Among patients of non‐Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, 56.3% (belimumab) and 47.7% (placebo) of patients were responders (P = 0.0407). While those receiving belimumab in both ethnic groups reported statistically significant improvements at week 52 (compared with placebo), the numerical difference was greater in the Hispanic or Latino group.

In the third and fourth quartiles for baseline body weight, significantly more patients who received belimumab were SRI4 responders than patients who received placebo (Figure 4). For the first and second quartiles, the differences between treatment arms did not achieve statistical significance.

The SRI4 response at week 52 was significantly greater in belimumab‐treated patients who were receiving corticosteroids at baseline compared with placebo‐treated patients receiving corticosteroids at baseline (Figure 4). There was no significant difference in SRI4 response at week 52 between belimumab and placebo among patients who were not taking corticosteroids at baseline.

FACIT‐Fatigue scores

Scores on the FACIT‐Fatigue scale improved over time in both treatment groups. The mean change from baseline was significantly greater in the belimumab group as compared with the placebo group at weeks 8, 36, and 52 (adjusted mean change at week 52 was 4.4 versus 2.7; P = 0.0130) but not at weeks 4, 12, and 24. The percentage of patients with an improvement in the FACIT‐Fatigue score of ≥4 also generally increased over time. At week 52, more patients who received belimumab had an improvement of ≥4 compared with placebo (44.4% versus 36.1%; OR 1.42 [95% CI 1.05–1.94]; P = 0.0245).

Time to first renal flare

Fewer patients with baseline proteinuria >0.5 gm/24 hours in the belimumab group (11 of 99) had a renal flare compared with those in the placebo group (13 of 48) (11.1% versus 27.1%; HR 0.40 [95% CI 0.18–0.90]; P = 0.0272). The median time to first renal flare for patients with baseline proteinuria >0.5 gm/24 hours who experienced a flare was 83.0 days (IQR 33.0–192.0) for belimumab versus 113.0 days (IQR 85.0–229.0) for placebo. In the overall population, fewer patients in the belimumab group had a renal flare as compared with placebo, although this difference was not statistically significant (4.7% versus 7.5%; HR 0.57 [95% CI 0.32–1.01]; P = 0.0532). All first renal flares had occurred by week 40 and week 48 in the belimumab and placebo groups, respectively.

Safety

Overall, 449 patients in the belimumab group (80.8%) and 236 patients in the placebo group (84.3%) experienced at least 1 AE (Table 2). The most common types were infections and infestations. SAEs were reported for 10.8% and 15.7% of patients, respectively. The most common types were infections and infestations, renal and urinary disorders, and nervous system disorders. Treatment‐related AEs were reported for 31.1% of the belimumab group and 26.1% of the placebo group. For further details, see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 (available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.40049/abstract).

Table 2.

Summary of AEs reported during the studya

|

Placebo (n = 280) |

Belimumab 200 mg SC (n = 556) |

|

|---|---|---|

| All AEs by system organ class | ||

| AEsb | 236 (84.3) | 449 (80.8) |

| Infections and infestations | 159 (56.8) | 308 (55.4) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 68 (24.3) | 125 (22.5) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 66 (23.6) | 124 (22.3) |

| Nervous system disorders | 53 (18.9) | 111 (20.0) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 60 (21.4) | 80 (14.4) |

| SAEsc | 44 (15.7) | 60 (10.8) |

| Infections and infestations | 15 (5.4) | 23 (4.1) |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 7 (2.5) | 8 (1.4) |

| Nervous system disorders | 6 (2.1) | 8 (1.4) |

| Treatment‐related AEs | 73 (26.1) | 173 (31.1) |

| AEs resulting in study discontinuation | 25 (8.9) | 40 (7.2) |

| AEs of special interest | ||

| Malignancies | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) |

| Postinjection systemic reactionsd | 25 (8.9) | 38 (6.8) |

| Serious | 0 | 0 |

| Serious delayed nonacute hypersensitivity reactionsd | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| All infections | 21 (7.5) | 30 (5.4) |

| Serious | 3 (1.1) | 8 (1.4) |

| Opportunistic infectionsd | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) |

| Serious | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

| Herpes zoster | 13 (4.6) | 18 (3.2) |

| Serious | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

| Sepsis | 3 (1.1) | 6 (1.1) |

| Serious | 2 (0.7) | 4 (0.7) |

| Depression | 10 (3.6) | 15 (2.7) |

| Serious | 0 | 0 |

| Serious suicidal ideationd | 0 | 2 (0.4) |

| Suicidal behaviord | 0 | 0 |

| Deaths | 2 (0.7) | 3 (0.5) |

Values are the number (%) of patients reporting the event. SC = subcutaneous.

Adverse events (AEs) that occurred in ≥20% of patients in either treatment group are listed.

Serious adverse events (SAEs) that occurred in >2% of patients in either treatment group are listed.

As adjudicated by GlaxoSmithKline physicians.

Local injection site reactions occurred in 34 patients in the belimumab group (6.1%) and 7 patients in the placebo group (2.5%). All were mild or moderate in severity, and no serious or severe injection site reactions were reported. The incidence of hypersensitivity reactions was similar between treatment groups. Three deaths were reported in the belimumab group (0.5%; 3 infections [bacterial sepsis, urosepsis, and tuberculosis of the CNS]) and 2 were reported in the placebo group (0.7%; 1 vascular [cardiac death] and 1 SLE‐related [thrombocytopenia]). Herpes zoster was reported in 18 patients in the belimumab group (3.2%) and 13 patients in the placebo group (4.6%); 1 case was serious (belimumab group). Fifteen patients in the belimumab group (2.7%) and 10 patients in the placebo group (3.6%) experienced depression; none of these episodes were serious. Two cases of serious suicidal ideation (0.4% taking belimumab, as adjudicated by GlaxoSmithKline physicians) and no cases of suicidal behavior were reported.

Four patients experienced worsening of IgG hypoglobulinemia from grade 0 to grade 2 in each treatment group (0.7% receiving belimumab and 1.4% receiving placebo). An additional case of worsening from grade 0 to grade 4 occurred in the belimumab group (0.2%).

The incidence of AEs was higher in both groups among patients in the highest body weight quartile (≥78.25 kg; 86.3% of the belimumab group and 90.0% of the placebo group) as compared with those in the lowest body weight quartile (<55.05 kg; 76.3% of the belimumab group and 77.1% of the placebo group).

Pharmacokinetics

The median plasma concentration in the group taking belimumab increased from week 4 (65.0 μg/ml) to week 24 (104.8 μg/ml), and decreased slightly at week 52 (86.8 μg/ml) (Supplementary Figure 1, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.40049/abstract).

DISCUSSION

This was the first phase III randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study to investigate the safety and efficacy of belimumab 200 mg SC plus standard SLE therapy in patients with SLE. The results demonstrate that weekly SC doses of belimumab 200 mg plus standard SLE therapy significantly reduced SLE disease activity as early as week 16. The treatment effect for belimumab SC is consistent with that observed with belimumab 10 mg/kg IV in the phase III, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled BLISS‐52 and BLISS‐76 studies 17, 18. The present study was designed to test the efficacy of belimumab SC rather than its equivalence (or lack of same) to belimumab IV, so no conclusion can be drawn with regard to equivalence. Nevertheless, the 2 previous belimumab IV trials and the present belimumab SC trial each met their respective primary end points and demonstrated consistent and significant clinical benefits of belimumab plus standard SLE therapy in patients with SLE.

The inclusion criteria for this study required a SELENA–SLEDAI score of ≥8 at screening, whereas the IV BLISS‐52 and BLISS‐76 studies required a SELENA–SLEDAI score of ≥6 17, 18. This requirement for a higher SELENA–SLEDAI was driven by data from the IV studies that highlighted that patients needed a higher level of disease activity at baseline in order to have the opportunity to achieve the 4‐point reduction in SELENA–SLEDAI that was needed to meet the SRI4 end point. Despite that requirement, the mean baseline SELENA–SLEDAI scores in the present study were similar to those in the IV studies (10.0 and 9.5 for belimumab 10 mg/kg, 9.7 and 9.8 for placebo in the BLISS‐52 and BLISS‐76 studies, respectively). A greater proportion of patients in the present study had SELENA–SLEDAI scores of ≥10 (62%), as compared with those in the BLISS‐52 (53%) and BLISS‐76 (51%) studies 17, 18.

A post hoc analysis of the present (BLISS‐SC) study and the pooled BLISS‐52 and BLISS‐76 studies was undertaken to compare only patients with SELENA–SLEDAI scores of ≥8 at baseline. In this analysis, the SRI4 responses at week 52 were 63.2% for belimumab 200 mg SC versus 50.0% for placebo and 57.4% for belimumab 10 mg/kg IV versus 41.7% for placebo (data on file; GlaxoSmithKline). While no head‐to‐head comparison between SC and IV belimumab was done, the results of the present study and of this post hoc analysis suggest consistency across the IV and SC studies.

Belimumab SC demonstrated further efficacy benefits, such as reduction of severe flare by 49% over 52 weeks, onset of action as early as week 16, and a shorter time to first SRI4 response that was maintained through week 52 compared with placebo. Significant reductions in severe flare were observed with belimumab 10 mg/kg IV over 52 weeks in the BLISS‐52 study 18 and with belimumab 1 mg/kg IV over 76 weeks in the BLISS‐76 study 17. Onset of action was also comparable to that in the BLISS‐52 and BLISS‐76 studies 17, 18. In addition, more patients in the belimumab SC group were able to reduce their corticosteroid dosage as compared with those in the placebo group, although this reduction did not achieve statistical significance. The decrease in corticosteroid dosage occurred in parallel with the reduction in risk of flare among those who received belimumab treatment compared with placebo. Since only patients receiving a baseline corticosteroid dosage >7.5 mg/day were eligible for analysis, the absence of statistical significance may reflect insufficient power to detect such a difference in a subgroup of this size. It should be noted that the study design did not mandate or encourage corticosteroid taper, and treatment blinding may have limited the proactive reduction of corticosteroids due to concerns that a patient may have been receiving placebo. The observed reduction in corticosteroid use may therefore not faithfully reflect clinical practice, where a more aggressive approach to corticosteroid tapering might be taken.

In subgroup analyses, patients with SELENA–SLEDAI scores of ≥10 at baseline had significant treatment responses (SRI4) with belimumab, whereas those with scores of ≤9 did not. The difference in response rates in the subgroup with scores ≥10 appeared to be greater than in the overall population, suggesting that belimumab SC may be especially beneficial in patients with high levels of disease activity. Similarly, belimumab‐treated patients who were receiving corticosteroids at baseline had a significant treatment response relative to placebo‐treated patients, consistent with the findings of a post hoc analysis of the BLISS‐IV studies 35. In the present study, the treatment effect on the SRI4 response in black patients indicated a positive trend, but statistical significance was not achieved. The number of patients in this subgroup was low, and the power was insufficient to draw firm conclusions. A separate study is underway to specifically assess the benefits of belimumab in black patients.

In baseline body weight subgroup analyses, the treatment effect did not appear to vary greatly between body weight subgroups. The effect achieved statistical significance for the third and fourth quartiles, but not for the first and second quartiles. As with other subgroup analyses, the patient numbers were low.

Fatigue is one of the most commonly reported symptoms among patients with SLE and has considerable impact on their lives 36. Patient‐reported fatigue was significantly reduced with belimumab SC at weeks 8, 36, and 52 in the present study. Although the time to first renal flare was reduced in patients receiving belimumab 200 mg SC, few renal flares occurred later in the study in this group, resulting in a shorter median time to flare. Patients receiving belimumab experienced fewer renal flares overall, and fewer patients with baseline proteinuria >0.5 gm/24 hours who were receiving belimumab experienced a renal flare as compared with those receiving placebo. Renal involvement is associated with increased morbidity in SLE 37, and a post hoc analysis of BLISS‐52 and BLISS‐76 study data suggested that belimumab may have beneficial effects in patients with renal involvement 38. However, while these data are encouraging, they offer no insight into efficacy in patients with severe active lupus nephritis, a subgroup that was excluded from the BLISS IV and SC studies 17, 18.

The safety profile of belimumab 200 mg SC plus standard SLE therapy was similar to that of placebo SC plus standard SLE therapy and was consistent with the known safety profile of belimumab IV 21. The overall incidences of AEs and SAEs were numerically lower in the belimumab group compared with the placebo group. The increase in AEs with increasing body weight was similar among patients receiving placebo and belimumab, suggesting that body weight did not affect the safety of belimumab.

The incidence of treatment‐emergent suicidality was low. Two patients in the belimumab group and none in the placebo group experienced serious suicidal ideation, and there were no cases of suicidal behavior. In prior studies of IV belimumab (phase II and 2 phase III studies), there were 2 completed suicides in the belimumab groups (2 of 1,458 [0.1%]) and none in the placebo groups (0 of 675), and serious depression was reported in 0.4% (6 of 1,458) of patients receiving belimumab and 0.1% (1 of 675) of patients receiving placebo 17, 18, 29, 39. In a phase III trial of SC tabalumab, another BLyS antagonist, in SLE, cases of depression and suicidal ideation were more common in the tabalumab groups (120 mg every 2 or 4 weeks) compared with placebo, although the overall incidence was low (depression, 4.0% and 4.5% versus 0.8%; suicide attempts, 0.3% and 0.5% versus 0%; suicidal ideation, 3.0% and 5.3% versus 0.4%; and suicidal behavior, 0.9% and 1.3% versus 0.4%) 40. Other studies of tabalumab did not report such an imbalance 41. Similarly, no cases of suicidal ideation or behavior were reported in patients with SLE taking other BLyS antagonists blisibimod 42, 43 or atacicept 44, 45, 46.

The efficacy and safety results in this study support fixed dosing with the SC dose selection of 200 mg (as opposed to the weight‐based dosing used for the IV infusion) 24. The pharmacokinetic profile is consistent with the simulated steady‐state concentrations for weekly belimumab 200 mg SC (104 μg/ml) and monthly belimumab 10 mg/kg IV (110 μg/ml) 25.

Some aspects of this study may limit interpretation. Not all patients were included in the corticosteroid reduction analyses, as only 503 of 836 (60.2%) patients were receiving corticosteroids at a dosage of >7.5 mg/day at baseline. The inclusion criteria did not permit inclusion of patients with SELENA–SLEDAI scores of <8 at screening, nor did they permit entry of patients with active nephritis or active CNS disease, so no conclusions can be made about these subsets of patients. Sample sizes in some subgroups were small, which limits the conclusions that can be drawn.

In summary, fixed‐dose weekly belimumab 200 mg SC in patients with SLE reduced SLE disease activity in the overall population, and patient‐reported levels of fatigue were improved. Safety results were consistent with the known safety profile of belimumab. The ability of patients with SLE to administer their medication away from the clinic will provide a more convenient treatment regimen for belimumab, which may make it a more viable treatment option for some patients.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Dr. Stohl had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design

Stohl, Kleoudis, Bass, Fox, Roth, Gordon.

Acquisition of data

Stohl, Schwarting, Okada, Scheinberg, Doria, Hammer, Kleoudis, Groark, Bass, Fox, Roth, Gordon.

Analysis and interpretation of data

Stohl, Schwarting, Okada, Scheinberg, Doria, Hammer, Kleoudis, Groark, Bass, Fox, Roth, Gordon.

ROLE OF THE STUDY SPONSORS

GlaxoSmithKline plc (GSK) designed, conducted, and funded the study, contributed to the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and supported the authors in the development of the manuscript. All authors, including those employed by GSK, approved the content of the submitted manuscript. GSK is committed to publicly disclosing the results of GSK‐sponsored clinical research that evaluates GSK medicines and, as such, was involved in the decision and to submit the manuscript for publication. Medical writing and editorial assistance was funded by GSK and was provided by Louisa Pettinger, PhD (Fishawack Indicia Ltd).

ADDITIONAL DISCLOSURES

Author Kleoudis is an employee of Parexel.

Supporting information

Supplementary Figure S1. Belimumab concentration.

Supplementary Table S1. AEs occurring in ≥5% of patients in either treatment group (preferred term)

Supplementary Table S2. Treatment‐related AEs occurring in ≥2% of patients in either treatment group (preferred term)

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01484496.

Supported by GlaxoSmithKline (BLISS‐SC identifier: BEL112341) and Human Genome Sciences, Inc., a subsidiary of GlaxoSmithKline.

Dr. Stohl has received consulting fees and/or honoraria from Akros Pharma, Jansen, Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer (less than $10,000 each). Dr. Schwarting has received speaking fees (less than $10,000) and research grants from GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Okada has received speaking fees and/or honoraria from Santen Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Pfizer, and Abbott Japan (less than $10,000 each). Dr. Scheinberg has received consulting fees from Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Epirus, Samsung Bioepis, and Janssen (less than $10,000 each). Dr. Doria has received speaking fees and/or honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline and Eli Lilly (less than $10,000 each). Ms Hammer, Ms Kleoudis, and Mr. Gordon, and Drs. Groark, Bass, Fox, and Roth own stock or stock options in GlaxoSmithKline.

REFERENCES

- 1. Schneider P, MacKay F, Steiner V, Hofmann K, Bodmer JL, Holler N, et al. BAFF, a novel ligand of the tumor necrosis factor family, stimulates B cell growth. J Exp Med 1999;189:1747–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moore PA, Belvedere O, Orr A, Pieri K, LaFleur DW, Feng P, et al. BLyS: member of the tumor necrosis factor family and B lymphocyte stimulator. Science 1999;285:260–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thompson JS, Schneider P, Kalled SL, Wang L, Lefevre EA, Cachero TG, et al. BAFF binds to the tumor necrosis factor receptor–like molecule B cell maturation antigen and is important for maintaining the peripheral B cell population. J Exp Med 2000;192:129–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Do RK, Hatada E, Lee H, Tourigny MR, Hilbert D, Chen‐Kiang S. Attenuation of apoptosis underlies B lymphocyte stimulator enhancement of humoral immune response. J Exp Med 2000;192:953–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Batten M, Groom J, Cachero TG, Qian F, Schneider P, Tschopp J, et al. BAFF mediates survival of peripheral immature B lymphocytes. J Exp Med 2000;192:1453–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gross JA, Johnston J, Mudri S, Enselman R, Dillon SR, Madden K, et al. TACI and BCMA are receptors for a TNF homologue implicated in B‐cell autoimmune disease. Nature 2000;404:995–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Khare SD, Sarosi I, Xia XZ, McCabe S, Miner K, Solovyev I, et al. Severe B cell hyperplasia and autoimmune disease in TALL‐1 transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000;97:3370–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mackay F, Woodcock SA, Lawton P, Ambrose C, Baetscher M, Schneider P, et al. Mice transgenic for BAFF develop lymphocytic disorders along with autoimmune manifestations. J Exp Med 1999;190:1697–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheema GS, Roschke V, Hilbert DM, Stohl W. Elevated serum B lymphocyte stimulator levels in patients with systemic immune–based rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:1313–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stohl W, Metyas S, Tan SM, Cheema GS, Oamar B, Xu D, et al. B lymphocyte stimulator overexpression in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: longitudinal observations. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:3475–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang J, Roschke V, Baker KP, Wang Z, Alarcón GS, Fessler BJ, et al. Cutting edge: a role for B lymphocyte stimulator in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol 2001;166:6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hong SD, Reiff A, Yang HT, Migone TS, Ward CD, Marzan K, et al. B lymphocyte stimulator expression in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus and juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:3400–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Petri M, Stohl W, Chatham W, McCune WJ, Chevrier M, Ryel J, et al. Association of plasma B lymphocyte stimulator levels and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:2453–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jacob CO, Pricop L, Putterman C, Koss MN, Liu Y, Kollaros M, et al. Paucity of clinical disease despite serological autoimmunity and kidney pathology in lupus‐prone New Zealand mixed 2328 mice deficient in BAFF. J Immunol 2006;177:2671–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ramanujam M, Wang X, Huang W, Liu Z, Schiffer L, Tao H, et al. Similarities and differences between selective and nonselective BAFF blockade in murine SLE. J Clin Invest 2006;116:724–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baker KP, Edwards BM, Main SH, Choi GH, Wager RE, Halpern WG, et al. Generation and characterization of LymphoStat‐B, a human monoclonal antibody that antagonizes the bioactivities of B lymphocyte stimulator. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:3253–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Furie R, Petri M, Zamani O, Cervera R, Wallace DJ, Tegzova D, et al. A phase III, randomized, placebo‐controlled study of belimumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits B lymphocyte stimulator, in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:3918–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Navarra SV, Guzman RM, Gallacher AE, Hall S, Levy RA, Jimenez RE, et al. Efficacy and safety of belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011;377:721–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. US Food and Drug Administration . FDA approves Benlysta to treat lupus. March 9, 2011. URL: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm246489.htm.

- 20. European Medicines Agency . Summary of product characteristics: Benlysta (belimumab). September 2011. URL: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002015/human_med_001466.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124.

- 21. Benlysta (belimumab) prescribing information. Rockville (MD): GlaxoSmithKline; 2014. URL: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/125370s016lbl.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chilton F, Collett RA. Treatment choices, preferences and decision‐making by patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Musculoskeletal Care 2008;6:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Struemper H, Murtaugh T, Gilbert J, Barton ME, Fire J, Groark J, et al. Relative bioavailability of a single dose of belimumab administered subcutaneously by prefilled syringe or autoinjector in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2016;5:208–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cai WW, Fiscella M, Chen C, Zhong ZJ, Freimuth WW, Subich DC. Bioavailability, pharmacokinetics, and safety of belimumab administered subcutaneously in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2013;2:349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yapa SW, Roth D, Gordon D, Struemper H. Comparison of intravenous and subcutaneous exposure supporting dose selection of subcutaneous belimumab systemic lupus erythematosus phase 3 program. Lupus 2016;25:1448–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. World Medical Association . WMA declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. URL: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html. [PubMed]

- 27. Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus [letter]. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Petri M, Kim MY, Kalunian KC, Grossman J, Hahn BH, Sammaritano LR, et al, for the OC‐SELENA Trial. Combined oral contraceptives in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2550–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Furie RA, Petri MA, Wallace DJ, Ginzler EM, Merrill JT, Stohl W, et al. Novel evidence‐based systemic lupus erythematosus responder index. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1143–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Petri M, Buyon J, Kim M. Classification and definition of major flares in SLE clinical trials. Lupus 1999;8:685–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Petri M, Kim MY, Kalunian KC, Grossman J, Hahn BH, Sammaritano LR, et al. Combined oral contraceptives in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2550–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Buyon JP, Petri MA, Kim MY, Kalunian KC, Grossman J, Hahn BH, et al. The effect of combined estrogen and progesterone hormone replacement therapy on disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:953–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cella D, Yount S, Sorensen M, Chartash E, Sengupta N, Grober J. Validation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Fatigue Scale relative to other instrumentation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2005;32:811–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Alarcon‐Segovia D, Tumlin JA, Furie RA, McKay JD, Cardiel MH, Strand V, et al. LJP 394 for the prevention of renal flare in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: results from a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:442–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Van Vollenhoven RF, Petri MA, Cervera R, Roth DA, Ji BN, Kleoudis CS, et al. Belimumab in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: high disease activity predictors of response. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1343–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tench CM, McCurdie I, White PD, D'Cruz DP. The prevalence and associations of fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:1249–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ward MM. Changes in the incidence of end‐stage renal disease due to lupus nephritis, 1982‐1995. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:3136–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dooley MA, Houssiau F, Aranow C, D'Cruz DP, Askanase A, Roth DA, et al. Effect of belimumab treatment on renal outcomes: results from the phase 3 belimumab clinical trials in patients with SLE. Lupus 2013;22:63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wallace D, Navarra S, Petri M, Gallacher A, Thomas M, Furie R, et al. Safety profile of belimumab: pooled data from placebo‐controlled phase 2 and 3 studies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2013;22:144–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Merrill JT, van Vollenhoven RF, Buyon JP, Furie RA, Stohl W, Morgan‐Cox M, et al. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous tabalumab, a monoclonal antibody to B‐cell activating factor, in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: results from illuminate‐2, a 52‐week, phase III, multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:332–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Isenberg DA, Petri M, Kalunian K, Tanaka Y, Urowitz MB, Hoffman RW, et al. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous tabalumab in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: results from ILLUMINATE‐1, a 52‐week, phase III, multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:323–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Furie RA, Leon G, Thomas M, Petri MA, Chu AD, Hislop C, et al. A phase 2, randomised, placebo‐controlled clinical trial of blisibimod, an inhibitor of B cell activating factor, in patients with moderate‐to‐severe systemic lupus erythematosus, the PEARL‐SC study. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1667–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stohl W, Merrill J, Looney R, Buyon J, Wallace D, Weisman M, et al. Treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus patients with the BAFF antagonist “peptibody” blisibimod (AMG 623/A‐623): results from randomized, double‐blind phase 1a and phase 1b trials. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Isenberg D, Gordon C, Licu D, Copt S, Rossi CP, Wofsy D. Efficacy and safety of atacicept for prevention of flares in patients with moderate‐to‐severe systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): 52‐week data (April‐SLE randomised trial). Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:2006–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pena‐Rossi C, Nasonov E, Stanislav M, Yakusevich V, Ershova O, Lomareva N, et al. An exploratory dose‐escalating study investigating the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intravenous atacicept in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2009;18:547–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dall'Era M, Chakravarty E, Wallace D, Genovese M, Weisman M, Kavanaugh A, et al. Reduced B lymphocyte and immunoglobulin levels after atacicept treatment in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a multicenter, phase Ib, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, dose‐escalating trial. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:4142–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1. Belimumab concentration.

Supplementary Table S1. AEs occurring in ≥5% of patients in either treatment group (preferred term)

Supplementary Table S2. Treatment‐related AEs occurring in ≥2% of patients in either treatment group (preferred term)