Abstract

Background

Onchocerciasis (river blindness) is endemic mostly in remote and rural areas in sub-Saharan Africa. The treatment goal for onchocerciasis has shifted from control to elimination in Africa. For investment decisions, national and global policymakers need evidence on benefits, costs and risks of elimination initiatives.

Methods

We estimated the health benefits using a dynamical transmission model, and the needs for health workforce and outpatient services for elimination strategies in comparison to a control mode. We then estimated the associated costs to both health systems and households and the potential economic impacts in terms of income gains.

Results

The elimination of onchocerciasis in Africa would avert 4.3 million–5.6 million disability-adjusted life years over 2013–2045 when compared with staying in the control mode, and also reduce the required number of community volunteers by 45–53% and community health workers by 56–60%. The elimination of onchocerciasis in Africa when compared with the control mode is predicted to save outpatient service costs by $37.2 million–$39.9 million and out-of-pocket payments by $25.5 million–$26.9 million over 2013–2045, and generate economic benefits up to $5.9 billion–$6.4 billion in terms of income gains.

Discussion

The elimination of onchocerciasis in Africa would lead to substantial health and economic benefits, reducing the needs for health workforce and outpatient services. To realise these benefits, the support and collaboration of community, national and global policymakers would be needed to sustain the elimination strategies.

Key questions.

What is already known about this topic?

The treatment goal of onchocerciasis has shifted from control to elimination in Africa where most infected cases exist.

The African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control has developed a conceptual framework for elimination, and previous studies modelled alternative elimination strategies based on the conceptual framework and showed that elimination strategies are cost-saving when compared with staying in a control mode.

What are the new findings?

This study shows the benefits the elimination strategies would bring about in terms of health and economic gains and the impacts on health systems.

The study predicts that the elimination strategies would lead to disability-adjusted life years averted due to prevented skin itch, low vision and blindness, the reduction in health workforces associated with community-directed onchocerciasis treatments and the reduction in the use of outpatient services and associated out-of-pocket payments.

Recommendations for policy

This study could be used by regional and global donors for their funding decisions on onchocerciasis elimination programmes by providing the quantitative prediction on health and economic benefits associated with onchocerciasis elimination strategies in comparison to staying in a control mode.

Introduction

Onchocerciasis (river blindness) is a parasitic disease transmitted by blackflies. Notable symptoms include severe itching, skin lesions and vision impairment including blindness. The disease is endemic in parts of Africa, Latin America and Yemen, and more than 99% of all cases are found in sub-Saharan Africa.1 Onchocerciasis affects the poor population in remote and rural areas, resulting in negative socioeconomic impacts on them. Fortunately, morbidity has been significantly decreased in Africa mainly through the vector control activities in West Africa under the Onchocerciasis Control Programme (OCP) over 1975–2002 and the community-directed treatment with ivermectin (CDTi) in sub-Saharan Africa and parts of West Africa within the framework of the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control (APOC) since 1995.2 Studies in Mali, Senegal and Uganda and the verified elimination in Colombia (2013), Ecuador (2014), Guatemala (2016) and Mexico (2015) showed that onchocerciasis elimination is feasible through ivermectin administration.1 3 4 The feasibility of elimination in addition to the successful control programmes have provided policymakers and donors with a justification to pursue the elimination of onchocerciasis, as shown by the WHO roadmap for neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) and the London declaration on NTDs.5 6

To invest in onchocerciasis elimination, given the limited resources and competing priorities, national and global policymakers and donors need information on the expected costs and impacts of potential elimination strategies. To generate this information, we assess the potential health and economic impacts in Africa associated with the control and elimination scenarios (box 1).

Box 1. Brief description of scenarios (Source: Kim et al7).

Control scenario: to keep the disease prevalence at a locally acceptable level, annual CDTi is implemented for at least 25 years, and afterwards epidemiological surveillance is conducted to evaluate whether CDTi can be stopped.

Elimination scenario I (African endemic countries without feasibility concerns): to reduce the incidence of infection to zero in a defined area (endemic areas without epidemiological and political concerns), annual or biannual CDTi is implemented and regular epidemiological and entomological surveillance is implemented to track epidemiological trends to decide a proper time to stop CDTi and to detect and respond to recrudescence early.

Elimination scenario II (all African endemic countries): to reduce the incidence of infection to zero in Africa, tailored treatment approaches in addition to annual/biannual CDTi are implemented to deliver sustainable treatments to all endemic areas including challenging areas with epidemiological and political concerns. Regular epidemiological and entomological surveillance is implemented to track epidemiological trends, to decide a proper time to stop CDTi, and to detect and respond to recrudescence early.

Methods

We compared the impacts of the control and elimination scenarios in Africa in health, economic and health system aspects. The time horizon for our analysis is from 2013 to 2045: the initial year was decided considering epidemiological and budget data for the previous epidemiological and cost analysis, which forms a basis for our analysis, were available up until 2012 and the end year was decided, as the earliest expected last year of treatment in the alternative elimination scenarios is early 2040s.7 8 The health and economic impacts were discounted with 3%.

Assessment of the health impact

To evaluate the health impacts of onchocerciasis elimination, we compared the prevalence of severe itching, low vision, and blindness and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) between the elimination scenarios and the control scenario. To predict the trends in the prevalence of the three symptoms by age group for the period 2013–2045, we ran simulations using the dynamical transmission model ONCHOSIM.9 We used the methods that Coffeng et al10 used to evaluate the health impacts of ivermectin treatments under the APOC, in which ivermectin was assumed to relieve severe itching by killing 99% of microfilariae, whereas its effect on reversing some forms of vision impairment (eg, due to punctate keratitis) was not considered, and also accounting for the infection type (savanna or forest), the precontrol endemicity level, the history of treatment coverage and the start year of treatment at project level (implementation unit), all of which were available from APOC databases. The precontrol endemicity level (none, hypo, meso, hyper) was defined for APOC countries based on the precontrol nodule prevalence among adult men, and for former OCP countries based on precontrol microfilariae prevalence among people aged 5 years and above7 (see online supplementary appendix I). For the entire time horizon, we assumed that treatment coverage would be stable at the level of average treatment coverage over 2010–2012 for APOC countries, and at the most recent treatment coverage level for former OCP countries due to the lack of history data. If the average treatment coverage was below 65%, the required minimum for effective control,11 we used the highest treatment coverage achieved during 2010–2012 as the expected treatment coverage. We assumed that if the country decides to shift the goal from control to elimination, treatment coverage will go up at least to the highest level achieved. For potential new projects, we used the national average treatment coverage and, if there were no relevant data, we used the regional average (across available national averages in either APOC or former OCP regions). For the new projects, we used the predicted start years based on donors' strategic plans and epidemiological and political situations in Kim et al.7

bmjgh-2016-000158supp_appendix.pdf (1.5MB, pdf)

We estimated the number of cases by multiplying the predicted prevalence of each symptom by the population living in endemic areas at project level. Community census data for 2011 were available for all projects from the APOC REMO (Rapid Epidemiological Mapping of Onchocerciasis) database, and we adjusted for country-specific population growth rates over 2013–2045.12

To compute DALYs, we estimated the years of life with disability (YLD), multiplying the number of prevalent cases of each symptom by a relevant disability weight, namely 0.187 for severe itching, 0.033 for low vision and 0.195 for blindness.13 We then calculated the years of life lost (YLL) by assigning 8 years of life expectancy loss for each blindness incidence based on the average onset age of blindness and the assumption of 50% reduction in remaining life expectancy.10

The methodological details for evaluating health impacts are described in online supplementary appendix I.

Impacts on health workforce

CDTi has been the primary approach for onchocerciasis treatment in Africa. In CDTi, community volunteers play a central operational role by deciding when and how to distribute drugs, administering drugs, managing adverse reactions, keeping records and reporting to health workers.14 Community health workers train community volunteers, monitor and evaluate CDTi performance, and report to health workers at higher levels to support informed decision-making.15 We estimated the number of community volunteers and community health workers required for implementing CDTi under each scenario. We multiplied the population living in endemic areas by the respective ratio of necessary community volunteers and community health workers over population, using the predicted timelines for the treatment phase at project level for each scenario.7 The ratios of required community volunteers and of community health workers over population were available from 2012 budget documents for 67 of total 112 APOC projects in sub-Saharan Africa (as of November 2013). We assumed that the ratios would be stable until the last year of CDTi. For projects without relevant ratios, we used a national average ratio and, if there were no national average data, we used a regional average ratio.

Impact on the use of outpatient services and associated costs

To assess the impact of onchocerciasis elimination on the use of health services, we predicted the number of outpatient visits and the associated financial costs to health systems and households for each scenario. To predict the number of outpatient visits, we multiplied the predicted number of patients with severe itching and low vision by the health facility usage rate at project level for the pre-CDTi period. As a proxy for the health facility usage rate, we used the average treatment coverages for the first year of CDTi, available from the APOC database for multiple endemic African countries (mean: 40%, SD: 15%),16 assuming that the proportion of people seeking treatments in areas without CDTi is similar to the compliance rate in the first CDTi year.

We then estimated outpatient service costs, multiplying the predicted number of outpatient visits by a country-specific outpatient cost per visit available in the WHO-CHOICE (CHOsing Interventions that are Cost Effective) database (see online supplementary table S4).

We estimated out-of-pocket payments, multiplying the outpatient service cost by a share of out-of-pocket expenditure (% of total health expenditure), and then adding transportation cost which is assumed to be 17% of out-of-pocket expenditure based on cross-country surveys17 (see online supplementary table S4).

Economic impacts

We estimated the potential economic benefits of onchocerciasis elimination by predicting income gains associated with the reduction in the prevalence of severe itching, low vision and blindness. This approach takes a view that disease prevention and treatment are an investment in human capital, and the value of investment can be quantified in terms of individuals' income gains.18 19

We estimated income losses by multiplying the predicted number of patients aged 15 years and above with severe itching, low vision and blindness by a country-specific employment rate and a proxy for income losses for each symptom under each scenario. We assumed that patients would have the same probability of being employed as general population unless they had onchocercal symptoms (see onlinsupplementary table S5). We assumed that patients aged from 15 to 64 years with severe itching would lose 19% of GDP (gross domestic product) per capita, and those with low vision and blindness would lose 38% and 79% of GDP per capita, respectively, based on surveys.20–22 Patients aged 65 years and above were assumed to earn half the income of those aged from 15 to 64 years.23 24 We also estimated income loss for informal caretakers (eg, families and relatives), assuming that one patient with low vision and blindness needs one adult caretaker. We assumed that the caretaker would lose 5% of GDP per capita if the patient has low vision, and 10% of GDP per capita if the patient is blind.24 25 To estimate income losses from mortality due to blindness, we multiplied the predicted YLL by GDP per capita, considering that blindness causes premature death at a fully productive age.26 To calculate income gains from elimination, we compared total income losses between the control scenario and the elimination scenarios.

Uncertainty analysis

We first conducted one-way deterministic sensitivity analysis (DSA) to examine the impact of a single parameter's uncertainty on the results and determine which parameters are key drivers. We then conducted probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) to assess the robustness of the results to the joint uncertainties about all selected parameters. For the PSA, we applied statistical distributions to parameters considering parametric characteristics and fitted to available data. Methodological details on PSA, including statistical distributions and data used for each parameter, are described in online supplementary appendix II.

Results

The predicted impacts of eliminating onchocerciasis in comparison to staying in the control mode are described in terms of health benefits, the required number of health workforces, the number of outpatient visits and associated costs, and economic benefits.

Health impacts

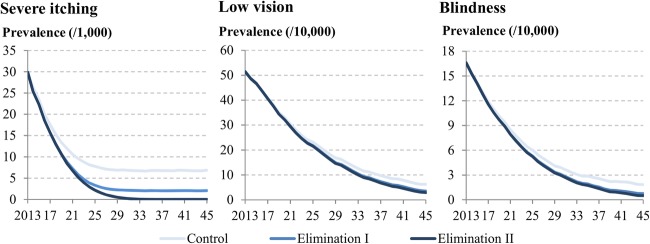

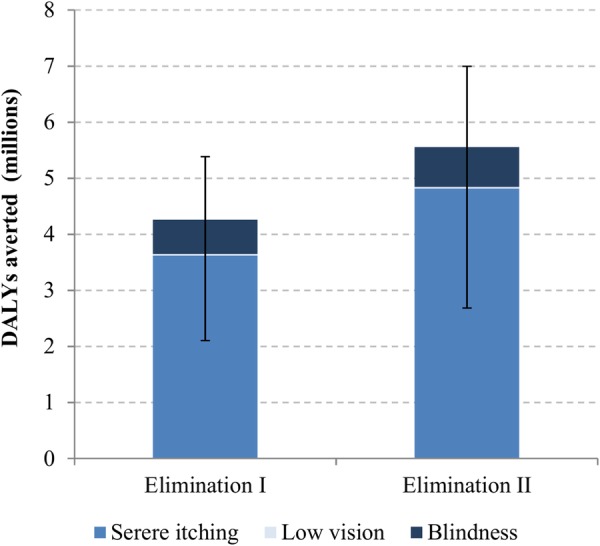

The control and elimination scenarios would lead to the decrease in the prevalence of the onchocercal symptoms (figure 1). The decrease in the prevalence of severe itching was faster than in those of low vision and blindness mainly due to a high effectiveness of ivermectin in killing microfilariae. The decrease in the prevalence of low vision was the slowest, because progression to blindness is largely prevented, resulting in more people staying in the stage of low vision. When compared with the control scenario, the elimination scenarios I and II would lead to DALYs averted by 4.3 million (2.1M−5.4M) and 5.6 million (2.7M−7.0M) years, respectively, over 2013–2045 (figure 2). The majority of DALYs averted are associated with the reduction in severe itching cases. The reasons for lowest DALYs averted for low vision are that the decrease in its prevalence is the slowest among the three symptoms, the disability weight for low vision is lower than those for skin itching and blindness and low vision contributes to only YLD, whereas blindness contributes to both YLD and YLL.

Figure 1.

Simulated trends in the prevalence of severe itching, low vision and blindness in endemic African regions over 2013–2045.

Figure 2.

Disability-adjusted life years averted for the elimination scenarios when compared with the control scenario in endemic African regions over 2013–2045. (The ranges are from probabilistic sensitivity analysis).

Impact on health workforce

The elimination scenarios I and II would lead to a reduction in the number of community volunteers required for implementing CDTi by 45% and 52%, respectively, or 10.7 million (5.9M−14.1M) and 12.4 million (6.9M−15.7M). Moreover, the total number of required community health workers would be reduced by 56% and 60%, respectively, or 1.3 million (0.5M−1.9M) and 1.4 million (0.6M−2.0M).

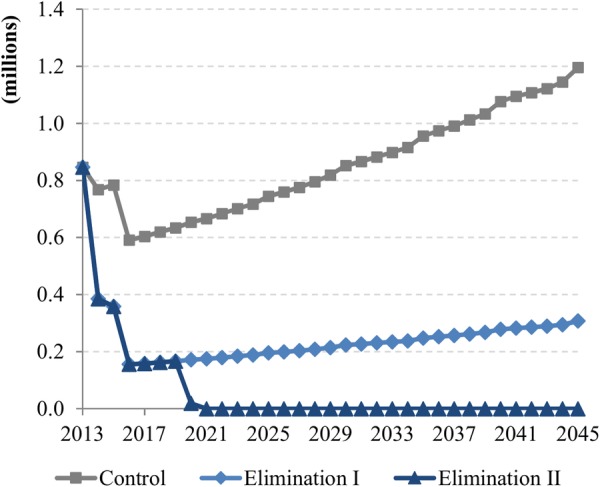

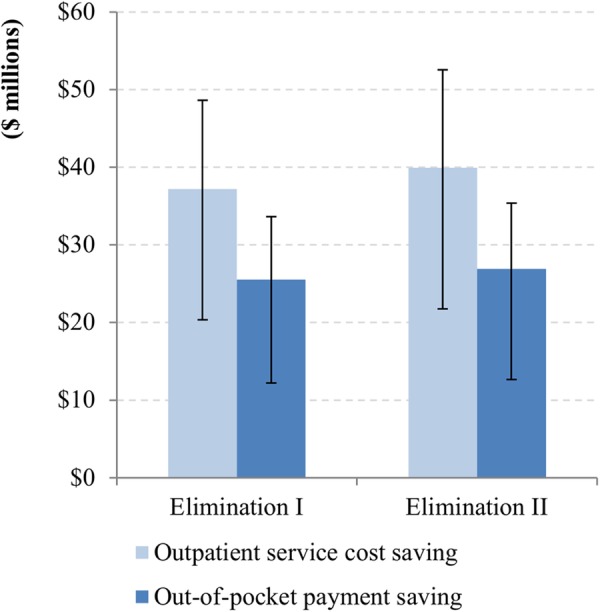

Impact on the use of outpatient services and associated costs

The elimination of onchocerciasis would reduce the financial burden on health systems and individuals associated with the use of outpatient services due to severe itching and low vision. The number of outpatient visits due to those symptoms is predicted to decrease from 846 000 in 2013 to 307 000 in 2045 in elimination scenario I and to <1000 in elimination scenario II, whereas it is predicted to increase to 1.2 million in the control scenario mainly due to population growth (figure 3). This would save outpatient service costs by $35.9 million ($17.8M–$47.1M) and $38.6 million ($19.1M–$50.0M) for the elimination scenarios I and II over 2013–2045, respectively, when compared with the control scenario; and out-of-pocket payments by $24.7 million ($12.2M–$33.6M) and $26.0 million ($12.7M–$36.4M), respectively (figure 4).

Figure 3.

Annual number of outpatient visits in endemic African regions over 2013–2045.

Figure 4.

The savings of outpatient service costs and out-of-pocket payments in endemic African regions for the elimination scenarios when compared with the control scenario over 2013–2045. (The ranges are from probabilistic sensitivity analysis.)

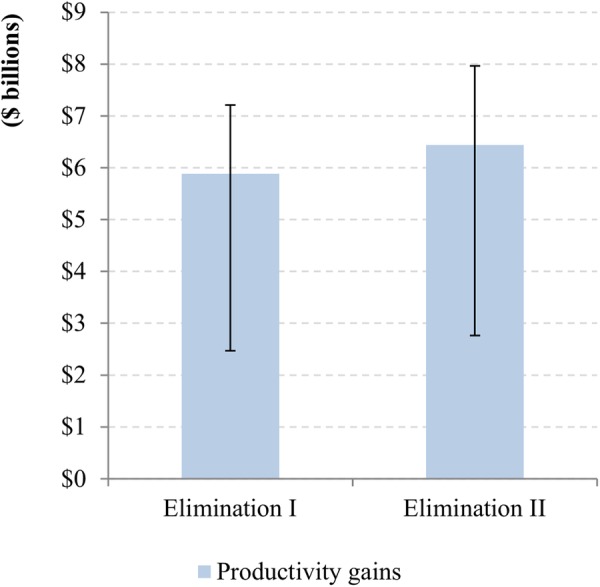

Economic impacts

The economic productivity benefits in terms of income gains for the elimination scenarios I and II when compared with the control scenario are predicted to be $5.9 billion ($2.5bn–$7.2bn) and $6.4 billion ($2.8bn–$8.0bn), respectively (figure 5). Income gains associated with the reduction in severe itching, low vision and blindness would account for 65%, 28% and 7% of total gains, respectively. Ninety-seven per cent of the income gains are expected to be associated with patients and the remaining 3% with their caretakers.

Figure 5.

Income gains in endemic African regions for the elimination scenarios when compared with the control scenario over 2013–2045. (The ranges are from probabilistic sensitivity analysis.)

Uncertainty analysis

One-way DSA indicated that the most influential parameter for the health impact results is the relative level of infection and morbidity in hypoendemic areas to mesoendemic areas (see online supplementary figure S1); for the health workforce needs, the ratio of community volunteers over population and that of community health workers over population (see online supplementary figures S2 and S3); for the savings of outpatient service costs and out-of-pocket payments, the number of patients with severe itching and health facility usage rate (see online supplementary figures S4 and S5); and for the income gains, the number of patients with severe itching, the income level during health years and the income loss due to skin itching (see online supplementary figure S6). Varying the discount rate from 0% to 6% leads the results to vary from 70% to 150% of the point estimates (see online supplementary figures S1 and S4–S6).

bmjgh-2016-000158supp_figures.pdf (97.6KB, pdf)

All results are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of key results (mean and 95% central range from probabilistic sensitivity analysis)

| Elimination I vs control (baseline) | Elimination II vs control (baseline) | |

|---|---|---|

| Health benefits, 2013–2045 | ||

| DALYs averted | 4.3 million (2.1M−5.5M) | 5.6 million (2.7M−7.2M) |

| Health systems impacts, 2013–2045 | ||

| Health workforce | ||

| Reduction in the number of required community volunteers | 10.7 million (5.9M−14.1M) | 12.4 million (6.9M−15.7M) |

| Reduction in the number of community health workers | 1.3 million (0.5M−1.9M) | 1.4 million (0.6M−2.0M) |

| Outpatients services | ||

| Outpatient service cost savings | $35.9 million ($17.8M–$47.1M) | $38.6 million ($19.1M–$50.0M) |

| Out-of-pocket payment savings | $24.7 million ($12.2M–$33.6M) | $26.0 million ($12.7M–$36.4M) |

| Economic benefits, 2013–2045 | ||

| Income gains | $3.9 billion ($2.5bn–$7.2bn) | $6.4 billion ($2.8bn–$8.0bn) |

Discussion

The results of this study show that scaling up treatments from mesoendemic/hyperendemic areas to hypoendemic areas along with regular epidemiological and entomological surveillance with the aim of elimination would lead to substantial health and economic benefits and reduce the burden on health systems in terms of health workforce and outpatient services. Kim et al8 showed in a cost analysis study that the elimination I and II scenarios, compared with the control scenario, would require a similar level of financial costs and significantly lower non-financial economic costs for programme operation over 2013–2045. These results imply that elimination programmes for onchocerciasis would save economic costs for conducting drug administration and surveillance in the long run when compared with control programmes and, at the same time, bring health and economic benefits to people.

Yet there are limitations that should be considered when the results are interpreted. First, although the model ONCHOSIM has been successfully validated by comparing the simulated trends of microfilaria prevalence and blindness to the empirical observations from multiple locations,10 27–31 it should be considered that the model uncertainties remain as it does not account for the possibility of recrudescence (due to unexpected or irregular factors such as civil conflicts, waning compliance to treatment, and human and vector migration), the effect of ivermectin on reversing some forms of vision impairment, the increase in mortality in infected, but not blind, people,32 and so on. Second, the expected last year of treatment could be earlier than 2040 in reality, especially if countries in need of treatment beyond 2030 to achieve elimination (Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Sudan) adopt 6-monthly treatment. Third, DALY was estimated using the new disability weights from the 2010 global burden of disease (GBD) study which raised concerns as the disability weights are different from those in the previous 2004 GBD study, especially the decreased weight for blindness from 0.594 to 0.195.13 33 Overall, DALYs averted in our analysis are higher by 2.0 million–5.6 million than those calculated using the previous disability weights. This is because the main driver of DALYs is the number of skin itching cases, the disability weight (0.187) of which is higher than the previous one (0.068), thereby offsetting the decreased DALYs averted due to low vision and blindness. Also, as shown in the sensitivity analysis (see online supplementary figure S1), for a more accurate estimation of DALYs averted, empirical data for the ratio of infection and morbidity in hypoendemic areas over mesoendemic areas will be required. Fourth, we assumed that the required number of community volunteers and community health workers for CDTi would be available in the estimation of workforce needs. However, the availability of these health workforces could change, for example, due to political circumstances and budgets allocated to keep and develop the health workforces. Fifth, we restricted the time horizon for analysis of the workforce needs to the treatment phase due to the lack of data on the workforce needs for the post-treatment surveillance period. In practice, policy-makers should consider that health workers will be needed for conducting and monitoring surveillance and responding to recrudescence after treatments are safely stopped. Sixth, as shown in the sensitivity analysis for the savings of outpatient service costs and out-of-pocket payments (see online supplementary figures S4 and S5), regular surveys on health facility usage and the relevant unit costs per person will be required for more reliable prediction. Seventh, in real life, income gains may be lower than our estimates, considering that onchocerciasis is concentrated among those with the lowest income, as shown in the lower bound of income gains in the sensitivity analysis (see online supplementary figure S6). More surveys on income and the impact of onchocerciasis on individual income will be needed for more robust economic evaluation. Finally, the economic impact can be evaluated from a more comprehensive perspective, by including psychological well-being gains as well as income gains. A study by Jamison et al34 based on willingness-to-pay studies estimated the economic value of one additional life year at 4.2 times GDP per capita for sub-Saharan Africa. Using their estimate, economic benefits from prevented mortality due to blindness are predicted to be at least four times higher than those in our study. This suggests that the economic impact evaluation is sensitive to a perspective and relevant methodological approaches.

Despite the limitations, the elimination scenarios are predicted to dominate the control scenario as they would lead to health and economic benefits with lower economic costs for operating treatment programmes in the long run. To realise these benefits, collaboration through well-defined arrangements, roles and responsibilities among all stakeholders at community, national and global levels will be critical as shown in the successful smallpox eradication.35 36 Cooperation from global donors and pharmaceutical companies through sustained funding and drug donation is particularly important, especially in the early stage of elimination programmes during which the needs for funding, health workforce and medicines will increase.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control (APOC) for sharing epidemiological and treatment databases.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola.

Twitter: Follow Fabrizio Tediosi @fabrizio2570

Contributors: YEK and FT designed the study. WAS and MT contributed to development of the strategies modelled. WAS contributed to the health impact analysis. YEK and FT did the analysis and wrote the first draft of the report. All authors contributed to data interpretation and writing of the final report.

Funding: This study is part of the Eradication Investment Case (EIC) of onchocerciasis, lymphatic filariasis and human African trypanosomiasis, grant #OPP1037660 of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF). WAS was funded by the NTD Modelling Consortium supported by BMGF in partnership with the Task Force for Global Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.WHO/APOC. Onchocerciasis. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs374/en/ (accessed 4 Dec 2016).

- 2.WHO/APOC. Report of the external mid-term evaluation of the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control. JAF16.8 WHO/APOC, 2010. http://www.who.int/apoc/MidtermEvaluation_29Oct2010_final_printed.pdf (accessed 25 Jan 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katabarwa MN, Walsh F, Habomugisha P et al. Transmission of onchocerciasis in Wadelai focus of northwestern Uganda has been interrupted and the disease eliminated. J Parasitol Res 2012;2012:748540 10.1155/2012/748540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Traore MO, Sarr MD, Badji A et al. Proof-of-principle of onchocerciasis elimination with ivermectin treatment in endemic foci in Africa: final results of a study in Mali and Senegal. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2012;6:e1825 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. Accelerating work to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases—a roadmap for implementation. WHO/HTM/NTD/2012.1. Geneva: WHO; 2012. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2012/WHO_HTM_NTD_2012.1_eng.pdf (accessed 25 Jan 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 6.London Declaration on neglected tropical diseases Uniting to Combat NTDs 2012. http://unitingtocombatntds.org/sites/default/files/resource_file/london_declaration_on_ntds.pdf (accessed 31 Mar 2015).

- 7.Kim YE, Remme JHF, Steinmann P et al. Control, elimination, and eradication of river blindness: scenarios, timelines, and ivermectin treatment needs in Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015;9:e0003664 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim YE, Sicuri E, Tediosi F. Financial and economic costs of the elimination and eradication of onchocerciasis (River Blindness) in Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015;9:e0004056 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plaisier AP, van Oortmarssen GJ, Habbema JDF et al. ONCHOSIM: a model and computer simulation program for the transmission and control of onchocerciasis. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 1990;31:43–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coffeng LE, Stolk WA, Zouré HG et al. African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control 1995–2015: model-estimated health impact and cost. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013;7:e2032 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO/APOC. Revitalising health care delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: the potential of community-directed interventions to strengthen health systems. Ouagadougou: WHO/APOC; 2007. http://www.who.int/apoc/publications/EN_HealthCare07_7_3_08.pdf (accessed 25 Jan 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 12.UN. World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision. http://esa.un.org/wpp/Excel-Data/population.htm (accessed 23 May 2014).

- 13.Salomon JA, Vos T, Hogan DR et al. Common values in assessing health outcomes from disease and injury: disability weights measurement study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013;380:2129–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO. APOC—community-directed distributor (CDDs) WHO 2014. http://www.who.int/apoc/cdti/cdds/en/ (accessed 5 Jul 2015).

- 15.WHO. APOC—community-directed treatment with ivermectin (CDTI) projects WHO 2008. http://www.who.int/apoc/cdti/howitworks/en/ (accessed 9 Apr 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amazigo U, Okeibunor JF, Matovu VF et al. Performance of predictors: evaluating sustainability in community-directed treatment projects of the African programme for onchocerciasis control. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:2070–82. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saksena P, Xu K, Elovainio R et al. Health services utilization and out-of-pocket expenditure at public and private facilities in low-income countries. World Health Report (2010) Background Paper, No 20 2010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.WHO. WHO guide to identifying the economic consequences of disease and injury. Geneva: WHO, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW et al. Cost-benefit analysis. In: Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW et al., eds Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005:211–46. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim A, Tandon A, Hailu A et al. Economic Impact of Onchocercal Skin Disease. Policy Research Working Paper. No. 1836 Washington, DC, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans TG. Socioeconomic consequences of blinding onchocerciasis in West Africa. Bull World Heal Organ 1995;73:495–506. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Workneh W, Fletcher M, Olwit G. Onchocerciasis in field workers at baya farm, teppi coffee plantation project, southwestern Ethiopia: prevalence and impact on productivity. Acta Trop 1993;54:89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frick KD, Foster A, Bah M et al. Analysis of costs and benefits of the Gambian Eye Care Program. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:239–43. 10.1001/archopht.123.2.239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith TS, Frick KD, Holden BA et al. Potential lost productivity resulting from the global burden of uncorrected refractive error. Bull World Health Organ 2009;87:431–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shamanna BR, Dandona L, Rao GN. Economic burden of blindness in India. Indian J Ophthalmol 1998;46:169–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alonso LM, Murdoch ME, Jofre-Bonet M. Psycho-social and economical evaluation of onchocerciasis: a literature review. Soc Med 2009;4:8–31. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plaisier AP, van Oortmarssen GJ, Remme J et al. The risk and dynamics of onchocerciasis recrudescence after cessation of vector control. Bull World Heal Organ 1991;69:169–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plaisier AP, van Oortmarssen GJ, Remme J et al. The reproductive lifespan of Onchocerca volvulus in West African savanna. Acta Trop 1991;48:271–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alley ES, Plaisier AP, Boatin BA et al. The impact of five years of annual ivermectin treatment on skin microfilarial loads in the onchocerciasis focus of Asubende, Ghana. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1994;88:581–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plaisier AP, Alley ES, Boatin BA et al. Irreversible effects of ivermectin on adult parasites in onchocerciasis patients in the onchocerciasis control programme in West Africa. J Infect Dis 1995;172:204–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ozoh GA, Murdoch ME, Bissek AC et al. The African programme for onchocerciasis control: impact on onchocercal skin disease. Trop Med Int Heal 2011;16:875–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walker M, Little MP, Wagner KS et al. Density-dependent mortality of the human host in onchocerciasis: relationships between microfilarial load and excess mortality. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2012;6:e1578 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salomon JA, Vos T, Murray CJL. Disability weights for vision disorders in Global Burden of Disease study—authors’ reply. Lancet 2013;381:23–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62131-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jamison DT, Summers LH, Alleyne G et al. Global health 2035: a world converging within a generation, the returns to investing in health (section 2). Lancet 2013;382:1898–955. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62105-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tarantola D, Foster SO. From smallpox eradication to contemporary global health initiatives: enhancing human capacity towards a global public health goal. Vaccine 2011;29(Suppl 4):D135–40. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klepac P, Metcalf CJE, McLean AR et al. Towards the endgame and beyond: complexities and challenges for the elimination of infectious diseases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2013;368:20120137 10.1098/rstb.2012.0137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2016-000158supp_appendix.pdf (1.5MB, pdf)

bmjgh-2016-000158supp_figures.pdf (97.6KB, pdf)