Abstract

Background

Universal health coverage (UHC) is critical to global poverty alleviation and equity of health systems. Many low-income and middle-income countries, including small island states in the Pacific, have committed to UHC and reforming their health financing systems to better align with UHC goals. This study provides the first comprehensive evidence on equity of the health financing system in Fiji, a small Pacific island state. The health systems of such states are poorly covered in the international literature.

Methods

The study employs benefit and financing incidence analyses to evaluate the distribution of health financing benefits and burden across the public and private sectors. Primary data from a cross-sectional survey of 2000 households were used to assess healthcare benefits and secondary data from the 2008–2009 Fiji Household Income and Expenditure Survey to assess health financing contributions. These were analysed by socioeconomic groups to determine the relative benefit and financing incidence across these groups.

Findings

The distribution of healthcare benefits in Fiji slightly favours the poor—around 61% of public spending for nursing stations and 26% of spending for government hospital inpatient care were directed to services provided to the poorest 20% of the population. The financing system is significantly progressive with wealthier groups bearing a higher share of the health financing burden.

Conclusions

The healthcare system in Fiji achieves a degree of vertical equity in financing, with the poor receiving a higher share of benefits from government health spending and bearing a lower share of the financing burden than wealthier groups.

Key questions.

What is already known about this topic?

Universal health coverage (UHC) is critical to global poverty alleviation and equity of health systems.

Studies have shown that a significant number of people worldwide do not have access to essential health services.

Many low-income and middle-income countries, including Fiji—a small Pacific island state, have committed to UHC and are reforming their health financing systems to better align with UHC goals.

Achieving UHC requires inter alia an equitable health financing system which distributes the burden of paying for healthcare according to ability to pay and benefits from health spending on the basis of need.

What are the new findings?

More than 70% of government spending for healthcare in Fiji is allocated to hospital services.

The healthcare system overall achieves a degree of vertical equity in financing, with the poor receiving a higher share of benefits from government health spending and bearing a lower share of the financing burden than wealthier groups.

The incidence of out-of-pocket payments for health in Fiji, unlike in many low and middle-income countries, is progressively distributed.

Recommendations for policy

The quality of health services for various providers in Fiji remains largely unknown and this currently limits policy discussions on access and usage of health services. There is an urgent need for evidence on the quality of care across different levels of the health system to complement information on the quantity of services used.

While the overall health financing system is progressive, indirect taxes such as value added tax and custom tax, remain regressive. The equity impact of these taxes needs to be comprehensively evaluated and appropriate mechanisms to lessen their impact on poorer households developedc.

Background

Inadequate access to quality healthcare remains widespread in many low and middle-income countries (LMICs), especially among the poor and vulnerable groups.1 An estimated 400 million people do not have access to at least one of the seven essential health services for achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).2 This recognition lends support to the current move and advocacy for universal health coverage (UHC) which has also been embedded in the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).2

In many countries, the inverse care law3 persists as those with the greatest need for quality health services do not receive a fair share of resources.4 Financial barriers are a major hindrance to accessing quality health services. Worldwide, some 1.2 billion people already living in poverty are pushed deeper into it as a result of using health services.2 Many governments in LMICs, including those in small island states in the Pacific, have committed to UHC and reforming their health financing system to better align with UHC goals. UHC seeks to provide people with the health services they need while protecting them against financial hardship from service usage.5 Achieving UHC requires, inter alia, an equitable health financing system which distributes the burden of paying for healthcare according to ability to pay (ATP) and benefits from health spending on the basis of need.5

Fiji is an upper-middle-income country in the Pacific islands with a gross national income per capita of $4870 and a population of nearly 900 000.6 It is one of the largest and most developed economies in the Pacific islands. Fiji's central location and vast natural resources make it an important regional player. Health indicators in Fiji compare favourably with its Pacific island neighbours. For example, maternal mortality in Fiji was 59 per 100 000 live births in 2013 compared with 120 per 100 000 in Tonga and 220 per 100 000 in Papua New Guinea.7 Fiji still faces significant economic and health challenges despite these achievements. Although overall poverty levels have declined, progress in rural areas is slow and lags behind urban areas.8 Non-communicable disease burden is high and rising in addition to the persistent infectious disease morbidity, making Fiji one of the many developing countries facing a double burden of disease, with a third emerging burden in accidents and injuries.9

Healthcare delivery in Fiji is organised at primary, secondary and tertiary levels. Primary healthcare (PHC) services are delivered through a network of 98 nursing stations, 84 health centres and 19 subdivisional hospitals.10 Nursing stations are the lowest health facility in Fiji, similar to health posts in some countries. They are located mainly in rural areas and serve as the first point of contact with the health system for many rural Fijians. Each of the country's four administrative divisions (Central, Northern, Western and Eastern) currently has at least 20 functional nursing stations. A nursing station is typically staffed by one registered nurse and caters for a catchment population of between 100 and 5000. They deliver the most basic of health services including maternal and child health services, such as immunisation, and also provide family planning information and services.11 Guidelines and policies exist in Fiji for the types of conditions that nurses can treat and manage in nursing stations and those that need to be referred to a higher level facility.9 Health centres, in contrast, are staffed by either a doctor or a nurse practitioner. The number of staff ranges from two to 20 depending on location and they usually serve a catchment population of between 3500 in a rural area and 10 000 in urban settings. Health centres provide comprehensive PHC services and also serve as the first level of referral for nursing stations. Provision of secondary care begins in subdivisional hospitals but more complex cases are referred to the three divisional and two specialised hospitals which provide secondary and tertiary level care. There are about 130 private general practitioner (GP) clinics in Fiji that provide services to complement health services provided in the public sector.9 These GP clinics are largely day clinics and provide general outpatient services.

The government of Fiji has recently endorsed a proposal to increase total government health spending to at least 5% of gross domestic product with the expressed aim of expanding access to quality services for the poor.12 The Ministry of Health and Medical Services (MoHMS) Corporate Plan 2015 notes the government is ‘examining a variety of healthcare financing options’ to promote financial risk protection.12 This will require robust evidence on who currently pays for and who benefits from health financing. This paper provides baseline evidence on equity of the current health financing system to inform the debate about pathways to UHC. Box 1 provides an overview of the health financing system in Fiji.

Box 1. Overview of health financing system.

The health system of Fiji is predominately public with government dominating the provision and financing of health services. Government health financing is exclusively from general taxation revenue as there is no social health insurance.13 Budgetary allocation to the MoHMS in 2012 accounted for 66% of total health expenditure, which was equivalent to 9.4% of overall government expenditure.7 This was higher than the 8.5% average government health spending for LMICs, but substantially lower than the WHO Western Pacific regional average of 14.4% and upper-middle-income countries average of 11.6%.7 Total health expenditure as a proportion of gross domestic product (GDP) was 4.0% in 2012, far better than for several countries in the Southeast Asian region, including Timor-Leste (1.4%) and Sri Lanka (3.1%). However, this was again below the WHO Western Pacific regional average of 6.6% and the upper-middle-income country average of 6.0%.7 The Fijian government recognises the need to raise the percentage of GDP allocated to healthcare but it is also keen to consider long-term financing alternatives that will reduce dependence on government funds and improve efficiency.12

Private health expenditure, particularly direct out-of-pocket (OOP) payments, account for more than one-third of total health expenditure in Fiji. OOP spending accounted for 73% of total private spending, or around 0.66% of GDP in 2014.13 Compared with several Southeast Asian countries where OOP spending is around 50% of total health expenditure,14 Fiji's OOP health spending of around 25.3% of total health expenditure in 2014 is relatively low, although across the Pacific islands it remains one of the highest.13 Donors play an important technical role in healthcare delivery in Fiji. However donor funding, estimated to be 4% of total health spending, is only a small component of overall health funding in Fiji.

In common with many LMICs, hospitals in Fiji account for the largest share of total health spending—around 71%.15 Providers of ambulatory care, health centres and nursing stations account for ∼10–12% of total health expenditure. There are 25 government hospitals (including two national referral hospitals) and three private hospitals providing secondary and tertiary care in Fiji. Private facilities do not receive government funding but there are several schemes that may result in public funds going to the private sector. For example, until 2014, the government was providing grants to the Kidney Dialysis Centre (a private facility) and also paying for the treatment of kidney patients. The payment for kidney treatment continues until today. Additionally, since 2015, the government has been paying private pharmacies to render services to public patients. Primary care is provided by a network of 84 health centres and 98 nursing stations.16 In general, health services provided by government facilities in Fiji are free of charge. Fijians use private services at their own expense.13

Methods

Approach

We employed two standard measures of health service usage and financing equity increasingly applied in LMICs—benefit incidence analysis (BIA) and financing incidence analysis (FIA). Standard BIA measures the extent to which different socioeconomic groups benefit from public spending for health through their use of health services.17 FIA (also called progressivity analysis) assesses the distribution of the burden of financing the health system across socioeconomic groups, and the extent to which this burden is proportionate with income.18 An equitable health financing system is one where payments for healthcare are related to ATP and healthcare benefits are distributed according to need.19

Data and analysis

A combination of primary and secondary data was used to assess the distribution of healthcare benefits and financing burden. For the BIA, we conducted a cross-sectional household survey involving 2000 households sampled from three of the four administrative divisions of Fiji. The three divisions have more than 90% of the population of Fiji. The 2000 households were sampled for statistical and pragmatic reasons. Statistically, given the size of Fiji, this number of households was judged adequate to provide reasonable estimates regarding the usage of health services. We worked closely with the Fiji Bureau of Statistics to ensure that this was as nationally representative as possible. On pragmatic grounds, the budget for the study could not support a bigger sample. Information gathered through the survey included rates of usage of health services, the costs incurred for using health services and household living standard data to enable the ranking of households by their socioeconomic status. Full details of the sampling procedure are published elsewhere (http://bmjopen.bmj.com/).20 We also obtained information on health expenditure for different types of services from the Fiji MoHMS. These data were used to calculate the unit costs of inpatient and outpatient services. For the FIA, we drew on existing secondary datasets, notably the 2008–2009 Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) and the 2011–2012 National Health Accounts. We obtained information about marginal tax rates and actual revenue from personal income tax, value added tax (VAT) and other taxes from the Fiji Revenue and Customs Authority and the Ministry of Finance. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval number: HC13269) and the Fiji National Health Research Committee (Approval number: 201371).

Analyses of the BIA and FIA data were undertaken using Stata 13. The BIA data analysis sought to ascertain whether the distribution of benefits from healthcare usage for a given provider was pro-poor or pro-rich and in line with the need for services. We used self-assessed health status by households to proxy health need.21 Self-assessed health status was measured by asking respondents in the survey to rate the health of members of their households. Four response categories ranging from ‘very good’ to ‘poor’ were provided. We followed the approach used by earlier studies in LMICs22 23 and classified individuals into two groups of need: good health (indicating no need for care) if they reported their health status to be very good or good; and poor health (indicating need for care) if they reported their health status to be fair or poor.

To determine healthcare benefit we multiplied the unit cost per service for a given provider by the rate of usage and deducted any out-of-pocket payments made.24 A concentration index (CI) was generated and used to measure the pro-poorness of the distribution of healthcare benefits. The CI, ranging from −1.0 to +1.0, captures the extent to which health payments are distributed among the economically worse off as compared with the better off.24

The FIA assessed equity in healthcare financing by evaluating the healthcare financing contribution across all socioeconomic quintiles. The sources of health financing in Fiji assessed in this study include taxation (direct and indirect), out-of-pocket payments and voluntary health insurance. Household per adult equivalent consumption expenditure was used as a proxy for income.25 To determine the progressivity or regressivity of health financing, we compared the concentration curves of the various financing sources with the Lorenz curve of income to determine if one dominates the other.24 The Lorenz curve illustrates the distribution of income across households, ranked in ascending order. The concentration curve plots the cumulative percentage share of healthcare payments for each household in the same ascending order as the Lorenz curve.19 We conducted a dominance test to ascertain whether any dominance was statistically significant.24 Next, we assessed the relative progressivity of each financing source using the Kakwani Index (KI). The KI compares the distribution of healthcare payments (plotted on the concentration curve), with the distribution of income (plotted on the Lorenz curve) to provide a summary measure of health system progressivity.26 The KI has values ranging from −2 to 1; a positive value indicates a progressive financing system and a negative value the opposite.26

Results

Distribution of healthcare benefits

More than 70% of government spending for healthcare in Fiji was allocated to hospital services. Hospital outpatient care accounted for nearly 47% of the total health spending for 2012, followed by inpatient care (30%). Less than 1% of the total spending was allocated to nursing stations. Private hospitals and clinics accounted for <7% of the total spending. Across all government health facilities, the distribution of healthcare benefits slightly favoured the poor. The poorest quintile received about 61% of the benefits from nursing stations, with only 2.4% going to the richest group (table 1) resulting in a high negative CI of −0.563. Benefit incidence for health centre and hospital outpatient and inpatient care also had negative CIs and were similarly pro-poor. The two poorest quintiles (poorest 40%) in total received slightly more than 41% of the benefits for health centre and public hospital outpatient care. Unlike nursing stations, the benefit incidence of these government facilities was more evenly distributed.

Table 1.

Distribution of healthcare benefits (percentage share)

| Public sector |

Private sector |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income quintile | Nursing station | Health centre | Hospital outpatient | Hospital inpatient | GP/clinic | Hospital outpatient | Hospital inpatient | Total benefit |

| Share of government subsidy | 0.7 | 16.2 | 46.5 | 30.1 | 1.8 | 4.3 | 0.5 | 100.0 |

| Q1-poorest | 61.2 | 17.6 | 15.9 | 25.5 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 18.5 |

| Q2 | 24.7 | 23.8 | 26.9 | 21.3 | 7.1 | 30.9 | 16.9 | 24.5 |

| Q3 | 7.2 | 26.9 | 23.3 | 27.3 | 20.0 | 9.8 | 10.4 | 24.3 |

| Q4 | 4.6 | 15.2 | 16.2 | 12.2 | 35.3 | 15.6 | 14.0 | 15.1 |

| Q5-richest | 2.4 | 16.5 | 17.7 | 13.8 | 36.9 | 41.4 | 58.6 | 17.8 |

| CI | −0.563 | −0.033 | −0.011 | −0.128 | 0.436 | 0.278 | 0.524 | −0.030 |

CI, concentration index; GP, general practitioner.

The distribution of the benefits for private health facilities was pro-rich. Thirty-seven per cent and 41% of the benefits for private GP clinics and private hospital outpatient services, respectively, went to the richest 20% of the Fijian population (table 1). The poorest 20% accounted for only 0.7% and 2.2%, respectively, of the benefits for GP clinics and private hospital outpatient care. The CI of 0.436 for GP clinics and 0.278 for private hospital outpatient care confirm the pro-rich distribution. Private hospital inpatient care was not used at all by the poorest quintile.

The total healthcare benefit, as shown by table 1, was mildly pro-poor with a CI of −0.030. The poorest 40% of the population receive a total of 43% of the benefit, compared with the richest 40%, who received ∼33% of the benefit. The highly pro-rich distribution of the private sector benefit did not significantly influence the overall distribution of healthcare benefit due to the small percentage of government funding going through the private sector (7%).

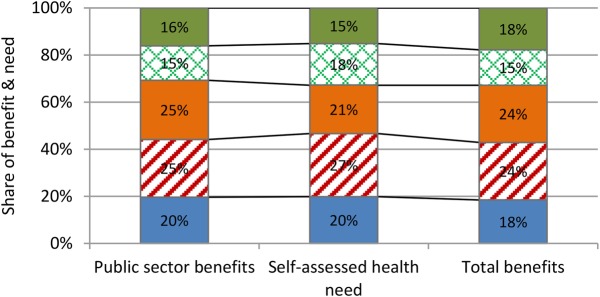

The distribution of healthcare benefits for the public sector as a whole was neither strongly pro-poor nor pro-rich when assessed in relation to the level of need observed in each socioeconomic group. For example, the poorest 40% of the population accounted for 47% of total self-assessed health need but received 45% of public sector benefit and 43% of the total benefit. In contrast, the richest 40% reported 33% of self-assessed health need but received 31% of public sector benefit and 33% of total benefit (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of healthcare benefits relative to need.

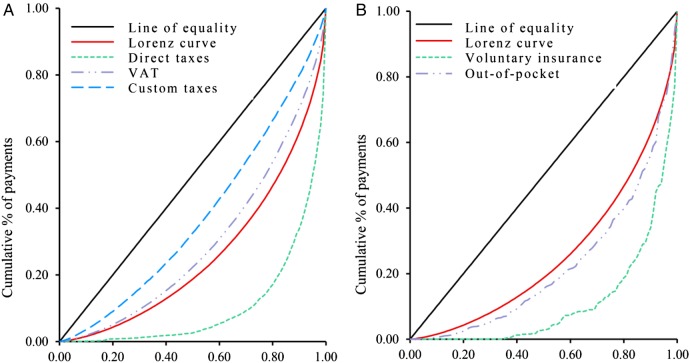

Distribution of health financing incidence

The results indicate that healthcare financing in Fiji is progressively distributed, with wealthier population groups making the greatest contribution. The concentration curves for direct taxes and private voluntary health insurance lie outside the Lorenz curve, indicating that they are progressive sources of health financing (figure 2A,B). More than 80% of the burden of these financing sources is borne by the richest quintile. Out-of-pocket payment was progressive with the richest 20% of the population contributing around 60%, compared with the <3% contribution made by the poorest 20%.

Figure 2.

Lorenz and concentration curves of taxes, private insurance premium and out-of-pocket payment.

Figure 2 also shows that indirect taxes, notably VAT and custom taxes, were regressive—that is, the relative burden of these taxes was concentrated among the poor. In absolute terms, the richest quintile contributed the largest share of these taxes (46% of VAT and 34% of custom taxes compared with 5% and 9%, respectively, contributed by the poorest quintile). However, relative to income, the contributions by the poorest quintile constituted 19% (VAT) and 15% (Customs), compared with 14% and 5% of income contribution by the richest quintile. Dominance tests showed the Lorenz curve dominating the concentration curves of direct taxes, voluntary insurance and out-of-pocket payments, confirming their progressivity. In contrast, the concentration curves for VAT and custom taxes dominate the Lorenz curve.

Table 2 confirms the strongly progressive distribution of direct taxes and private voluntary insurance—the KI was positive for both and in excess of 0.320 in magnitude. This means that the better off contribute the largest share of revenue raised from these sources of finance. The KI for out-of-pocket payment was also positive (0.098) indicating richer Fijians contribute more out-of-pocket to finance the health system than the poor. Finally, the negative KI for the indirect taxes affirms that poorer households contribute more of their income to revenues raised from these taxes. Table 2 shows that overall healthcare financing in Fiji is mildly progressive, with a positive KI of 0.041. This is driven largely by the relatively high progressivity of direct taxes and private voluntary health insurance.

Table 2.

Kakwani index of various financing sources and total health financing

| Payments | Weight | Concentration index | Kakwani index | Dominance test against Lorenz |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct taxes | 0.185 | 0.789 | 0.336 | + |

| Indirect taxes | 0.453 | 0.297 | −0.155 | |

| VAT | − | 0.410 | −0.043 | – |

| Custom taxes | − | 0.251 | −0.202 | – |

| Out-of-pocket payments | 0.287 | 0.551 | 0.098 | + |

| Voluntary insurance | 0.075 | 0.776 | 0.323 | + |

| Total health financing | 1.000 | 0.493 | 0.041 |

Dominance tests: + indicates the Lorenz curve dominates the concentration curve (progressive).

– indicates concentration curve dominates the Lorenz curve (regressive).

VAT, value added tax.

Discussion

Fiji's efforts to improve health equity are underpinned by a relatively fair distribution of healthcare benefits and a progressive financing system. The results of this study indicate that close to 93% of government spending for healthcare is concentrated in the public sector where the distribution of healthcare benefit is mildly pro-poor. Only about 7% of government spending goes to the private sector.

The distribution of nursing station benefits was found to be strongly pro-poor. Nursing stations are the first point of contact with the formal health system for rural residents in Fiji. However, their share of total health spending was <1%. Although, government expenditure on nursing stations has increased, rising from FJ$1.4 million in 2009 to FJ$1.9 million in 2010,13 the overall level of nursing station funding remains low. This mirrors the situation in many LMICs, where governments allocate significant shares of their health spending to hospital-based services, although they tend to be less accessible to the poor. In Vietnam, community health centres are pro-poor but they receive only 2.2% of government health spending.27 With around 47% of the population in Fiji living in rural areas,6 a well-resourced and well-functioning nursing station network could contribute significantly to the national goal of achieving health equity and UHC.

Unlike nursing stations, health centres and hospital outpatient services appear to be used by all Fijians. Benefits from these facilities were relatively evenly distributed, with the poorest and richest quintiles receiving almost equal shares. In several LMICs, benefits from outpatient care at the health centre and hospital levels have been found to be pro-poor. For example, in Thailand, the distribution of benefits from outpatient services provided by the Ministry of Public Health at the health centre, district and provincial hospital levels are all shown to be consistently pro-poor.26 In the case of Fiji, although the negative CIs for health centre and hospital outpatient services demonstrate a slightly pro-poor distribution of benefits, a closer look reveals a proportional rather than pro-poor distribution. Fijians of all socioeconomic status receive some benefits from public spending on outpatient care.

This result can be understood in the context of improved coverage and access to health services in Fiji. About 70–80% of the Fijian population reportedly has access to health services.9 PHC, in particular, has wider coverage partly as a result of the longstanding policy to strengthen health service delivery at the local level. For more than 35 years, Fiji has emphasised increasing coverage of PHC under the umbrella of the Healthy Islands initiative for Pacific Islands.12 As noted earlier, the country has a good network of health facilities (nursing stations, health centres and subdivisional hospitals) that provide primary and secondary care. At tertiary level, a range of services are provided through divisional and specialised hospitals. There are ∼1726 inpatient beds in Fiji—a ratio of about 2.05 beds per 1000 population.10 Recent reforms to decentralise outpatient services from divisional hospitals to health centres is believed to have further enhanced access to services.28 After a successful pilot programme to decentralise general outpatient services from the divisional hospital in Suva (the capital) to health centres in and around the capital,29 the MoHMS has rolled out the outpatient service decentralisation policy across all divisional hospitals in the country. This policy has led to the upgrade of several health centres, making them more capable of providing timely services. This may explain why the better off seek care in health centres as much as the poor. Staff shortages remain a challenge but efforts are also being made to improve human resource availability in the health system. A recent assessment of the health workforce situation has led to the Cabinet of Fiji approving the creation of 553 new positions over a 4-year period.30 A new Fiji Free Medicines Programme allows all eligible Fijians to access 72 prescription medicines free of charge from any government pharmacy or selected private pharmacies.31

The high outpatient spending accruing to the richest quintile may partly relate to the issue of access to private health facilities. O'Donnell and colleagues have observed that the extent to which higher income groups claim benefits from public healthcare is dependent on whether an attractive private sector alternative exists.32 They noted that ‘income-elastic demand for healthcare quality and convenience of service, will lead to greater substitution of private for public care by an expanding middle-class as the economy grows’.32 The private health sector in Fiji is small and relatively underdeveloped. This means the more sophisticated medical treatments can only be accessed in public facilities and it is common to see patients referred from private facilities to public hospitals. Outpatient departments in public facilities also have longer opening hours than private outpatient departments. The rather limited private sector in Fiji may explain why the better off continue to use outpatient services in the public sector and hence compete for subsidies with the poor.

While overall healthcare financing in Fiji was found to be slightly progressive, indirect taxes were regressive. This finding is in line with similar studies in LMICs. In South Africa, all indirect taxes have been shown to be regressive, including VAT.19 In Malaysia, despite the overall progressive healthcare financing system, indirect taxes are reportedly regressive.33 Indirect taxes, particularly VAT, are a major source of revenue for the Fijian government. In 2013, they contributed around 69% of total government revenue, with VAT alone contributing some 36%.8 As a tax on consumption, VAT tends to be regressive. In this study, we found that in absolute terms the better off contribute more in VAT than the poor, but as a proportion of gross consumption the poorest quintile contributes more than the richest (19% compared with 14%). Recent government action to streamline VAT collection is expected to bring some relief to poorer households. The VAT rate, which increased from 12.5 to 15% in 2011, was cut to 9% in January 2016.34 However; the anticipated relief may not be significant as the government has simultaneously removed from the list of zero-rated goods several food and basic items, such as tinned fish and kerosene, that are predominantly purchased by the poor.34

Direct taxes, voluntary health insurance and out-of-pocket payments were all found to be progressive in Fiji. Traditionally, direct taxes have been progressive in many LMICs.19 26 In Fiji, the progressivity of direct taxes is likely to have been intensified by recent government tax reforms resulting in substantial cuts in personal income and corporate taxes.8 However, these taxes make a relatively small contribution to overall healthcare spending. The dominance of indirect taxes in government revenue limits overall progressivity of healthcare financing.

As with many LMICs, fiscal space in Fiji is tightening and the government is embarking on policy reforms to prioritise and consolidate public spending.35 It remains to be seen how this will impact on government health spending generally and on the poor in particular. Out-of-pocket payments, unlike direct taxes, have been found to be regressive in many LMICs, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.19 However, several Asian countries have reported progressive out-of-pocket payments as observed in Fiji.26 33 A significant proportion of out-of-pocket spending in Fiji is linked to the purchase of pharmaceuticals from the private sector;13 pharmaceuticals are free through the public sector.

Limitations

The analysis in this paper has some limitations. First, we were unable to assess the quality of health services for various providers in Fiji as part of the BIA. Such an assessment would have made the results more comprehensive. Next, we drew on secondary data (HIES) for the FIA. Although the HIES was conducted with substantial technical assistance from the World Bank, it was only the second time Fiji had undertaken a nationally representative household socioeconomic survey, and hence, there were limitations in terms of the range of health variables included. Finally, there were no nationally representative health services usage data in Fiji at the time of this study. We therefore conducted our own household survey to gather primary data for the BIA. Although we covered the two main islands of Fiji with nearly 90% of the total population, the remaining islands were not covered. We minimised the potential effects of this on the results by using sampling methods and survey weighting to extrapolate the data to the national level.19

Conclusion

The health financing system in Fiji is equitable in terms of wealthier Fijians bearing a higher share of the financing incidence. The picture is less clear with regards to the distribution of benefits from public spending on health, especially when need is taken into account. The poorest 40% of the population received less total benefits than they would have if benefits were allocated on the basis of need. The private sector, on the other hand, is significantly pro-rich although the volume of activities and the share of total government funds going to the sector are very small. Overall, Fiji appears to be well on the path to UHC, but there is room for improvement. Given the highly pro-poor distribution of the nursing stations' spending, it will be reasonable for the government to boost funding to these facilities. In terms of the incidence of health financing, the equity impact of indirect taxes, particularly VAT, needs to be comprehensively investigated and appropriate mechanisms designed to lessen their effects on poorer households. To improve progressivity, the government needs to consider moving away from indirect taxes towards direct taxation as the major source of revenue for funding the health system.

The value of this study goes beyond supporting Fiji's progress towards UHC; there are lessons for Pacific island countries and other small island states planning their own path to UHC. As evident from this study, the overall health financing system of Fiji is progressive and this has been achieved with limited external funding. The UN SDGs emphasise mobilisation of domestic resources for healthcare.2 Fiji's domestic financing of healthcare demonstrates that regardless of size, the potential exists for upper-middle-income countries to mobilise resources internally to finance their health systems in a progressive manner.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Sanni Yaya.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the design of the study. AA led the drafting of the manuscript, which was reviewed and commented on by all authors.

Funding: This work was funded by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) through the Australian Development Research Awards (ADRAs) Scheme under an award titled ‘An assessment of equity in health care financing in Timor-Leste and Fiji’.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the DFAT or the Australian Government. The Commonwealth of Australia accepts no responsibility for any loss, damage or injury resulting from reliance on any of the information or views contained in his publication. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.WHO. Tracking universal health coverage: first global monitoring report. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Health in 2015: from MDGs, millennium development goals to SDGs, sustainable development goals. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hart JT. The inverse care law. Lancet 1971;1:405–12. 10.1016/S0140-6736(71)92410-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balarajan Y, Selvaraj S, Subramanian SV. Health care and equity in India. Lancet 2011;377:505–15. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61894-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kutzin J. Health financing for universal coverage and health system performance: concepts and implications for policy. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:602–11. 10.2471/BLT.12.113985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Bank. World development indicators 2015. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO. World health statistics 2015. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.IMF. Republic of Fiji: staff report for the 2013 Article IV Consultation. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts G, Irava W, Tuiketei T et al. . The Fiji Islands Health System Review. Health Systems in Transition 2011;1:1–150. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiji Ministry of Health. Health information bulletin 1st quarter 2016—using health information for measuring and improving health outcome. Suva, Fiji, Ministry of Health and Medical Services, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Negin J, Roberts G, Lingam D. The evolution of primary health care in Fiji: past, present and future. Pac Health Dialog 2010;16:13–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiji Ministry of Health and Medical Services. National Strategic Plan 2016–2020 Executive Version. Suva, Fiji: Fiji Ministry of Health and Medical Services, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiji Ministry of Health and Medical Services. Fiji Health Accounts National Health Expenditure 2011–2014. Suva, Fiji: Ministry of Health and Medical Services, Republic of Fiji, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.OECD. Health at a glance 2015: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiji Ministry of Health. Costing study for selected hospitals in Fiji. Suva, Fiji: Ministry of Health and Medical Services, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiji Ministry of Health and Medical Services. Ministry of Health Annual Report 2014. Suva, Fiji: Ministry of Health and Medical Services, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McIntyre D, Ataguba JE. How to do (or not to do)… a benefit incidence analysis. Health Policy Plan 2011;26:174–82. 10.1093/heapol/czq031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagstaff A, Lindelow M. Progressivity in the financing of decentralized government health programs: a decomposition. Health Econ 2007;16:1271–5. 10.1002/hec.1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mills A, Ataguba JE, Akazili J et al. . Equity in financing and use of health care in Ghana, South Africa, and Tanzania: implications for paths to universal coverage. Lancet 2012;380 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60357-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asante AD, Price J, Hayen A et al. . Assessment of equity in healthcare financing in Fiji and Timor-Leste: a study protocol. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006806 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manderbacka K. Examining what self-rated health question is understood to mean by respondents. Scand J Soc Med 1998;26:145–53. 10.1177/14034948980260020301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ataguba JE, McIntyre D. Paying for and receiving benefits from health services in South Africa: is the health system equitable? Health Policy Plan 2012;27(Suppl 1):i35–45. 10.1093/heapol/czs005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chuma J, Maina T, Ataguba J. . Does the distribution of health care benefits in Kenya meet the principles of universal coverage? BMC Public Health 2012;12:20 10.1186/1471-2458-12-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Donnell O, Van Doorslaer E, Wagstaff A et al. . Analyzing health equity using household survey data: a guide to techniques and their implementation. Washington DC: World Bank Publications, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deaton A, Zaidi S. Guidelines for constructing consumption aggregates for welfare analysis. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Limwattananon S, Vongmongkol V, Prakongsai P et al. . The equity impact of Universal Coverage: health care finance, catastrophic health expenditure, utilization and government subsidies in Thailand. Consortium for Research on Equitable Health Systems, Ministry of Public Health, http://r4d dfid gov uk/Output/188980 2011.

- 27.World Bank. Health equity and financial protection report—Vietnam. Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohammed J, North N, Ashton T. Decentralisation of health services in Fiji: a decision space analysis. Int J Health Policy Manag 2016;5:173–81. 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nand D. Decentralisation of general outpatient services from the Colonial War Memorial Hospital to the health centres in the Suva Subdivision. Fiji Journal of Public Health 2012;1:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiji Ministry of Health. Fiji Health Sector Support Program. Suva, Fiji: Ministry of Health and Medical Services, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fiji Ministry of Health. Pharanews Bulletin; Issue #1. Suva, Fiji: Ministry of Health and Medical Services, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Donnell O, van Doorslaer E, Rannan-Eliya RP et al. . The incidence of public spending on healthcare: comparative evidence from Asia. World Bank Economic Rev 2007;21:93–123. 10.1093/wber/lhl009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu CP, Whynes DK, Sach TH. Equity in health care financing: the case of Malaysia. Int J Equity Health 2008;7:15 10.1186/1475-9276-7-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiji Ministry of Finance. Economic and fiscal update—Supplement to the 2016 Budget Address. Suva: Ministry of Finance, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.ADB. Asian development outlook 2015: financing Asia's future growth. The Philippines: Asia Development Bank, 2015. [Google Scholar]