Abstract

Cortical spreading depolarizations are an epiphenomenon of human brain pathologies and associated with extensive but transient changes in ion homeostasis, metabolism, and blood flow. Previously, we have shown that cortical spreading depolarization have long-lasting consequences on the brains transcriptome and structure. In particular, we found that cortical spreading depolarization stimulate hippocampal cell proliferation resulting in a sustained increase in adult neurogenesis. Since the hippocampus is responsible for explicit memory and adult-born dentate granule neurons contribute to this function, cortical spreading depolarization might influence hippocampus-dependent cognition. To address this question, we induced cortical spreading depolarization in C57Bl/6 J mice by epidural application of 1.5 mol/L KCl and evaluated neurogenesis and behavior at two, four, or six weeks thereafter. Congruent with our previous findings in rats, we found that cortical spreading depolarization increases numbers of newborn dentate granule neurons. Moreover, exploratory behavior and object location memory were consistently enhanced. Reference memory in the water maze was virtually unaffected, whereas memory formation in the Barnes maze was impaired with a delay of two weeks and facilitated after four weeks. These data show that cortical spreading depolarization produces lasting changes in psychomotor behavior and complex, delay- and task-dependent changes in spatial memory, and suggest that cortical spreading depolarization-like events affect the emotional and cognitive outcomes of associated brain pathologies.

Keywords: Adult neurogenesis, cortical spreading depression, hippocampus, spatial memory

Introduction

Cortical spreading depolarization (CSD) is a self-propagating wave of neuronal and glial depolarization accompanied by near-complete breakdown of ion gradients and spontaneous electrical activity. Consequences are release of neurotransmitters, neuronal swelling, distortion of dendritic spines, and changes in blood flow and metabolism.1,2 Most of these parameters return to normal within several minutes. Despite such transient and largely benign course, CSD also has lasting consequences, for instance on cerebral gene expression and structure, indicating concomitant changes in brain function.3–5 In terms of structural plasticity, the most striking feature of CSD is the sustained increase in newborn dentate granule cells (DGCs) in the hippocampus, the central brain structure for explicit memory processing.5,6

In the adult hippocampus, new DGCs are continuously generated in the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus (DG). These new neurons pass through a continuous process of maturation and integration, eventually displaying characteristics similar to developmentally born DGCs.7–9 Accumulating evidence suggests that immature DGCs make unique contributions to hippocampal function.10–13 Indeed, between 3 and 5 weeks of age, they exhibit enhanced excitability, reduced inhibition, and stronger synaptic plasticity than mature DGCs, as indicated by a lower threshold for long-term potentiation.7,8 In addition, these new neurons are activated with higher probability than mature DGCs in response to afferent stimulation in vitro or to behavioral experience.14–17 However, behavioral studies suggest that immature DGCs are involved in hippocampus-dependent memory even earlier, at 1–3 weeks of age,18–21 when they just start to establish functional synapses, receive first weak glutamatergic input and are virtually unable to spike.7,8,22–24

Despite considerable evidence pointing towards an important role of CSD-like events in human brain pathologies,1,25 there is no systematic study on the long-term consequences of CSD on behavior. In the past, CSD has been applied as technique to reversibly abolish neuronal activity (i.e. functional decortication) for studying the role of different brain regions in behavior. These studies revealed comprehensive information about acute effects of CSD, such as impairments in postural reflexes, motor coordination, motivational behavior, or memory.26–28 Two of the previous studies extended their analysis to several days and found transient impairments in exploratory behavior, passive avoidance, and visual discrimination learning during days 3–5 after CSD.29,30

The present study was aimed to extend these findings by evaluating long-term consequences of CSD on non-mnemonic behavior and hippocampus-dependent memory. Two, four, or six weeks following CSD independent groups of mice were tested either in a Morris water maze (MWM) or in a Barnes maze (BM), both preceded by open field (OF) and location recognition testing. All mice received 5′-Iodo-2′-deoxyuridin (IdU) during the first week after CSD to assess adult neurogenesis.

Materials and methods

Animals and surgery

All procedures involving living animals were carried out according to the EC directive 86/609/EEC for animal experiments and were approved by the local Animal Care Committee (Thüringer Landesamt für Lebensmittelsicherheit und Verbraucherschutz). Experiments are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines. We used a total of 108 C57Bl/6J males, 10–12 weeks old at the time of surgery. Mice were group-housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. Experiments were carried out during the light phase. Induction of CSD was performed as described earlier for rats.5 Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane in a 2:1 N2O/O2 mixture and fixed in a stereotactic frame. Their rectal temperature was kept constant at 37 ± 0.5℃. Two craniotomies of 1.4 mm diameter were made above the right hemisphere at Bregma +1.5 mm, 1.5 mm lateral, and Bregma −2.5 mm; 2.0 mm lateral, with the dura mater left intact. An Ag/AgCl-reference electrode was placed subcutaneously in the neck. A glass electrode (impedance 2–4 MΩ) filled with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF: 120 NaCl, 2 CaCl2, 5 KCl, 1.8 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 1.25 NaH2PO4, and 10 Glucose; in mmol/L) containing an Ag/AgCl wire was placed on the dura at the anterior position and connected to a high impedance amplifier (EXT-08, NPI, Tamm, Germany). Amplified signals (100×) were continuously digitized and stored on a computer equipped with an A/D converter (CED 1401, Cambridge Electronic Design Ltd., Cambridge, England) and Spike 2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design Ltd.) to record the electrocorticogram (ECoG) and direct current (DC) potential. Recordings were allowed to stabilize, while anesthesia was successively reduced to 1.5% isoflurane. To induce CSD, a small swab soaked with 1.5 mol/L KCl was placed on the dura at the posterior craniotomy and renewed every 5 min. After a period of 110 min, the swab was removed, craniotomies were rinsed with aCSF, sealed with bone wax and the wound was closed at 2% isoflurane. Sham animals received 1.5 mol/L NaCl instead of KCl.

In general, animals were randomly assigned to the experimental groups (n = 8 in each sham group and n = 10 in each CSD group). From the surgery onwards, experimenters were blinded to group allocation.

Labeling of proliferating cells and tissue preparation

On six consecutive days after surgery, animals received daily injections of 5′-Iodo-2′-deoxyuridin (IdU; 57.5 mg/kg in sterile 0.9% NaCl/0.04 N NaOH; MP Biomedicals). During the period of spatial learning, animals received further injections of equimolar 5′-Chloro-2′-deoxyuridin (CldU; 42.5 mg/kg in sterile 0.9% NaCl; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) which was not analyzed for the present study. At the end of the behavioral test battery, mice were deeply anesthetized and transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer pH 7.4. The brains were removed and post-fixed in the same solution overnight at 4℃. After cryoprotection in increasing concentrations of sucrose (10% and 30% sucrose in 0.14 mol/L PBS, 4℃), brains were frozen in 2-methybutan (−25 to −30℃) and stored at −80℃.

Immunohistochemistry

Forty-micro meter coronal sections were treated for 30 min with 1.5% H2O2, denatured for 30 min in 2 N HCl, and neutralized in 0.1 mol/L borate buffer pH 8.5 for 10 min. Sections were blocked in TBSplus, containing 0.1% triton, 3% donkey serum, and donkey α-mouse Fab fragments (1:50; Dianova, Hamburg, Germany), and incubated over night at 4℃ with mouse α-BrdU antibody (AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK). Then, sections were consecutively incubated in biotinylated secondary antibody (donkey α-rat, 1:500; Dianova) for 3 h and Vectastain Elite ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 1 h, followed by DAB (3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride hydrate; Sigma-Aldrich) signal detection. All incubations were intermitted by repetitive rinsing in TBS.

Cell quantification

IdU-stained sections were counted in one-in-six series throughout the entire DG at a magnification of 400× (Axioplan 2 microscope; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Resulting numbers were multiplied by 6 to obtain an estimate of the total numbers of IdU-positive cells.

Behavioral tasks

BM and MWM performance were tested on independent cohorts of mice. To examine whether the behavioral effects of CSD are time-dependent, mice were trained either two, four, or six weeks after CSD (Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Table 1). Before BM or MWM training commenced, all mice were handled for two days and then consecutively examined in an OF and a location recognition task (Supplementary Figure 1). All tests were performed during the light phase. Prior to each test, animals were accustomed to the testing room for ≥45 min. Data were recorded and analyzed using an automated video tracking system (EthoVision 2.3 and XT 6.1.326, Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, The Netherlands) coupled to a CCD camera mounted above the test setup.

OF test

The OF test was used to examine exploratory behavior, locomotion as well as emotionality in response to a new and unfamiliar environment. The apparatus consisted of an opaque acrylic chamber (40 × 40 × 32 cm; illumination 20–25 lx) subdivided into a central (24 × 24 cm) and a peripheral zone. The test was started by placing a mouse into a randomly chosen corner and lasted for 10 min. Before testing the next animal, the chamber was cleaned with 70% ethanol. Time spent in different zones, distance moved, and rearing events were evaluated.

Location novelty recognition test

In this test, we assessed the mice’s ability to recognize changes in the spatial location of familiar objects (place recognition), which depends on an intact hippocampus.31 The apparatus design was similar to the OF but provided access to distal visual cues. One day before testing, animals were habituated to the chamber for 10 min. The test comprised a familiarization phase consisting of three 5-min trials at an interval of 20 min, and a 5-min recognition test performed with a delay of 20 min after the last trial. During familiarization, two identical objects were placed at constant positions close to two adjacent corners. For the recognition test, both of the objects were replaced by two identical objects with one of them moved to a new location. After each trial, the arena and objects were cleaned with 70% ethanol. Data were collected using the multiple body point module of EthoVision. Exploration was defined as directing the nose toward an object at a distance of ≤2 cm. Mice having their home base beside an object or exploring objects for less than 1 s were excluded from further analysis. Spatial discrimination was calculated using an exploration index (tn/(tn + tf)) which reflects the percentage of time animals spent exploring the displaced object (tn) in relation to the total exploration time (tn + tf).

BM

Spatial learning in a dry-land maze was tested using a setup as has been described earlier.32 The maze consisted of a circular white PVC platform, 90 cm in diameter, elevated 100 cm above the floor, and with 20 holes (5 cm in diameter) equally spaced along the perimeter. One of the holes lead to an escape box (17 × 8 × 6 cm, black PVC), whereas the others were closed with shutters made from the same material. An acrylic cylinder (20 cm in diameter, 10 cm high) placed in the center of the maze was used as start box. To increase mice’s motivation to escape, the platform was illuminated from above (∼800 lx). Distal visual cues were available for spatial navigation.

The protocol comprised habituation, six days of acquisition, a probe and a control trial. During habituation, mice were placed into the start box for 1 min, allowed to freely explore the platform for another minute and then placed into the escape box for 2 min. The next day, acquisition commenced with four daily trials at an inter-trial-interval of 2 min. Each trial, mice were placed into the start box for 20 s and then given 4 min to locate the escape box. Mice that failed to find the box were gently guided to it. All mice remained in the escape box for 1 min until returned to their cage. The location of the escape box remained constant for each mouse but varied between animals. To avoid orientation based on intra-maze cues (e.g. odors), the platform was cleaned with 70% ethanol between trials and rotated before each new session. As measure of spatial learning performance, we analyzed the path length, the number of errors (pokes into false holes), and the use of spatial search strategies. A spatial strategy was defined as finding the escape box after making 0 to 3 erroneous visits around the target hole. One week after acquisition, mice received two trials in which the escape box was relocated to a position 180° (probe trial) and 90° (control trial) relative to its original location. The first was intended to test animal’s spatial memory, the second to check whether animals use cues for navigation that do not require spatial memory and potentially bias the interpretation of the results.

MWM

Spatial learning and memory were further assessed in a MWM. It consisted of a circular pool (120 cm diameter and 40 cm height) filled with opaque water (24 ± 1℃), and an escape platform (9 cm in diameter). Testing was done in an indirectly lit room (26 lx) without (habituation and cued learning) or with (place learning) distal cues available for spatial navigation.

The protocol involved habituation, cued learning, place learning (acquisition), and a probe trial. At the beginning of each trial, mice were gently released into the pool at 1 of 4 semi-randomly chosen start locations (N, E, S, W). A trial generally lasted for 60 s or until the mouse escaped by climbing to the platform. Mice that failed were gently guided to the platform. Animals were allowed to stay there for 20 s and returned to a warm holding cage for an inter-trial-interval of 30 s. During habituation, animals were allowed to swim in the pool without a platform for 60 s in order to get acquainted with the test situation and to reduce stress during subsequent learning. On the next day, animals were assessed in four cued trials with a visible platform (0.5 mm above water surface, marked with a flag) placed at variable positions in the pool. Acquisition comprised two daily sessions of three trials with an intersession interval of 6 h and lasted for a total of seven days. Now, the platform was hidden 0.5 cm below the water surface in the center of the NW quadrant. To assess remote reference memory, mice were subjected to a single 60-s probe trial without a platform at one week after training. To evaluate learning performance, we analyzed the swim path length as well as the time spent in the four quadrants. Since during MWM place learning rodents typically display a progression from undirected or non-spatial (i.e. thigmotaxis, random search, scanning, chaining) to increasingly precise, spatial strategies (i.e. directed search, focal search, direct swimming), we furthermore assessed the search pattern animals used to locate the hidden platform, in order to distinguish hippocampus-independent (egocentric) from hippocampus-dependent (allocentric) search strategies. To categorize these strategies from time-coded XY-data, we applied a parameter-based algorithm in Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) as described by Garthe et al.33

Statistics

To examine the effects of CSD on cell numbers, as well as on OF and location novelty recognition test (LNR) behavior, we first evaluated our data using a Shapiro-Wilk test (SigmaPlot 13.0). If normality was given, t-tests or two-way ANOVAs were performed. Otherwise values were ln-transformed prior to testing. If data still violated t-test assumptions, we used a Mann–Whitney-U test. Measures of BM and MWM acquisition were analyzed with a two-way repeated measures ANOVA (2-way RM-ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. As an exception, search strategy use in the MWM was analyzed based on the generalized estimating equations method (Procedure GENLIN; IBM SPSS Statistics 21, IBM Corp., Armonk NY). Testing of BM probe and control trial performance was done with a Friedman test followed by Wilcoxon (hole preference within a group) or Mann–Whitney tests (between-group differences). Furthermore, we evaluated the relationship between CSD rate and dependent parameters (IdU numbers, behavior) using a Pearson’s correlation analysis (SigmaPlot 13.0). All data are presented as group mean±SEM, significance levels were set at 0.05.

Results

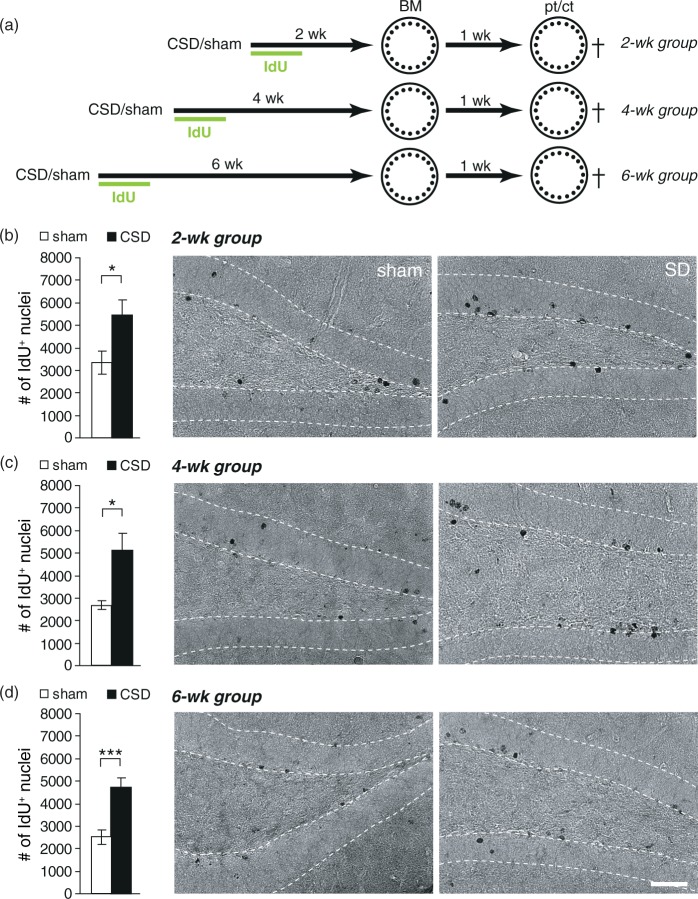

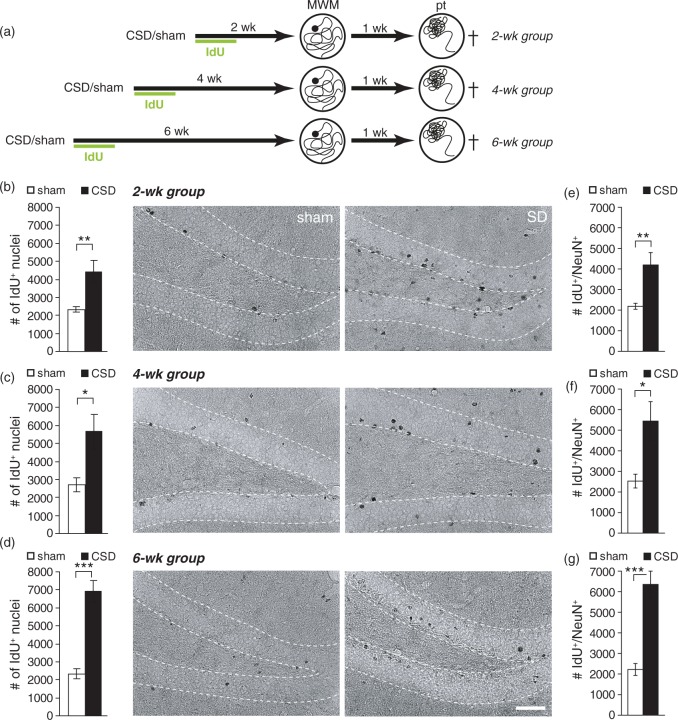

Epidural KCl application for 110 min elicited on average 9.7 ± 0.53 CSD (range 7–13 CSD), whereas sham mice displayed no deflections of the DC potential. Our previous studies on rats have shown that CSD strongly increased BrdU incorporation and neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. To determine if CSD had the desired effect on mouse hippocampal neurogenesis, we injected animals for six days post-surgery with IdU and analyzed IdU immunoreactivity immediately after behavioral testing. CSD increased the number of IdU-positive cells irrespective of the treatment-analysis delay (Figures 1, 2; CSD vs. sham: BM2wk P = 0.038, BM4wk P = 0.016, BM6wk P < 0.001; MWM2wk P = 0.002, MWM4wk P = 0.02, MWM6wk P < 0.001; t-test). Except in the MWM6wk group, this increase was restricted to the ipsilateral side and affected both, the suprapyramidal and the infrapyramidal blade of the DG (P > 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis test, Wilcoxon post hoc test for comparing ipsilateral vs. contralateral sides or suprapyramidal vs. infrapyramidal blades and Mann–Whitney post hoc test for comparing between groups; Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). In CSD and sham mice that had learned the BM (Figure 1(a) to (d)), as well as in sham mice learning the MWM (Figure 2(a) to (d)), numbers of IdU-positive cells were independent from the delay between IdU treatment and analysis. However, in CSD animals that had learned the MWM, numbers of IdU-positive cells significantly accumulated with increasing treatment-analysis intervals (MWM2wk vs. MWM6wk: P = 0.013, two-way ANOVA). This result indicates that MWM selectively increases the pool of 5–6 weeks old DGCs that were excessively born in response to CSD. To confirm that the newborn cells had a neuronal phenotype, we performed a double-labeling against IdU and NeuN (only MWM groups; Supplementary Figure 2). Independently of group or treatment-analysis delay, 95–96% of the newborn cells were immuno-positive for NeuN. Consequently, CSD mice showed a significant increase in double-positive cell numbers that was proportional to the changes observed for IdU-positive cells, indicating a significant increase in adult-born neurons (Figure 2(e) to (g)). The examination of histological sections of CSD and sham mice revealed no evidence for CSD-related neuronal damage in the dentate granule layer (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 1.

CSD-induced changes in dentate gyrus newborn cell numbers in the Barnes maze (BM) cohort. (a) Experimental timeline. After the induction of CSD, all animals received one daily injection of IdU for six days. BM training commenced either two, four, or six weeks following CSD and lasted for six days. One week after the last training, a probe (pt) and a control trial (ct) were performed. (b–d) Numbers and representative photomicrographs of newborn, IdU-positive cells in the 2 (b), 4 (c), and 6 (d) week groups; DAB staining. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001; t-test. Scale bar = 50 µm.

Figure 2.

CSD-induced changes in dentate gyrus newborn cell numbers in the Morris water maze (MWM) cohort. (a) Experimental timeline. After the induction of CSD all animals received one daily injection of IdU for six days. MWM training commenced either two, four, or six weeks following CSD and lasted for seven days. One week after the last training, a probe trial (pt) was performed to test spatial memory. (b–d) Numbers and representative photomicrographs of newborn, IdU-positive cells in the 2 (b), 4 (c), and 6 (d) week groups; DAB staining. (e–g) Numbers of newborn neurons (IdU/NeuN double-positive) in the 2 (e), 4 (f), and 6 (g) week groups. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistics: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; t-test. Scale bar = 50 µm.

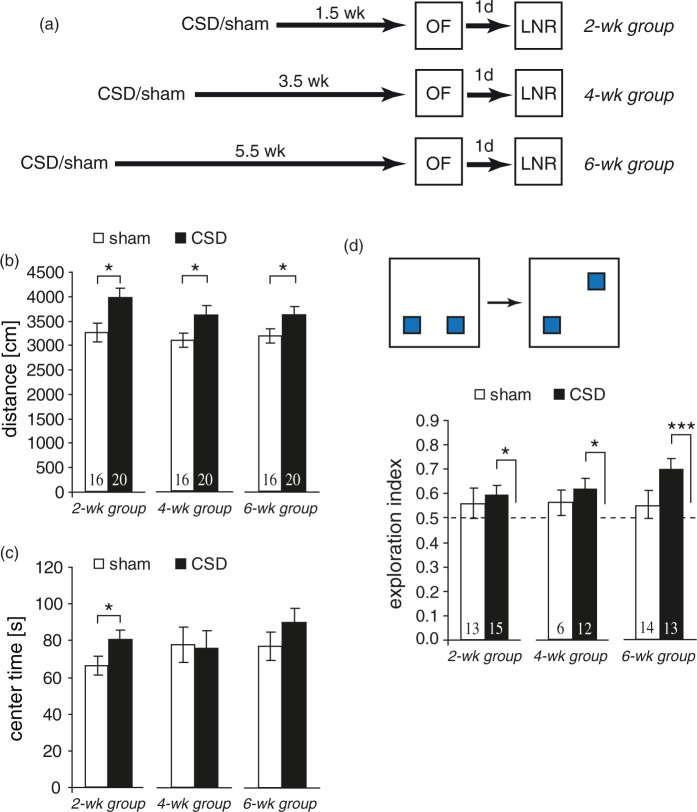

To assess potential changes in basic locomotor, exploratory and emotional behavior, we examined CSD mice in an OF. As shown in Figure 3(b), CSD mice exhibited higher levels of horizontal activity at all treatment-analysis intervals (distance CSD vs. sham: 2wk P = 0.02, 4wk P = 0.04, 6wk P = 0.05), and showed a tendency for increased vertical activity, especially in the 2wk group (rearing, P = 0.052; data not shown). At this early time point, CSD mice also spent significantly more time in the center zone (P = 0.05; Figure 3(c)). Furthermore, CSD increased defecation for up to four weeks (2wk: P = 0.015, 4wk: P < 0.001, Mann–Whitney-U test; data not shown).

Figure 3.

Time-dependent effects of CSD on open field behavior and place recognition memory. (a) Experimental timeline for the three groups. (b, c) Open field behavior. (d) Performance in the location novelty recognition task expressed as exploration index. Dashed lines represent chance level (0.5, equal exploration of both objects). Data are presented as mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; (b, c) t-test or Mann–Whitney-U test, (d) one-sample t-test against chance level. Numbers within bars represent the group size.

We next examined our mice in a location novelty recognition task, in which mice are tested for their ability to remember the location of familiar objects. The exploration index for CSD mice was significantly higher than chance level for all treatment-analysis intervals (2wk: P = 0.048, 4wk: P = 0.027, 6wk: P < 0.001, one-sample t-test; Figure 3(d)). In contrast, sham mice spent an equal amount of time exploring each object, reflected by an exploratory index very close to chance (P > 0.05, one-sample t-test).

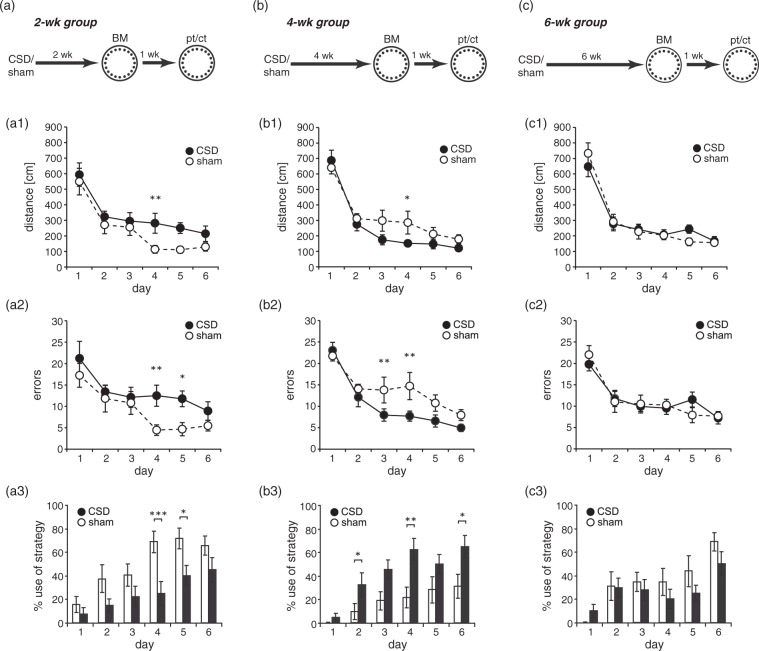

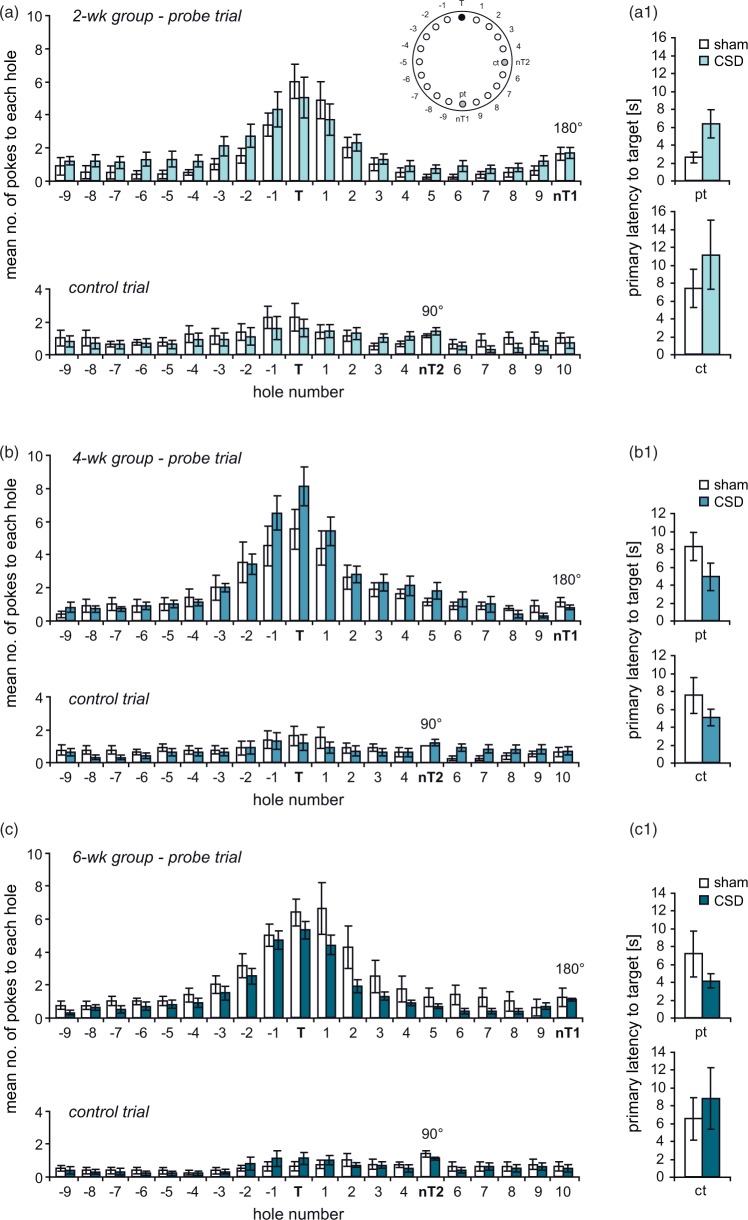

Spatial reference memory was tested in either a BM or a MWM. Both tests follow the same principle (finding a hidden escape at a constant location) and eventually measure hippocampus-dependent reference memory. The two tests were chosen because they differ in strength of reinforcement (water vs. light) and thus vary in their susceptibility to non-cognitive confounders like stress or exploratory drive.34 In the BM, all mice significantly improved across the six days of training. Two-way RM-ANOVA revealed a decrease in distance (2wk: F(5,80) = 21.233, P < 0.001; 4wk: F(5,80) = 52.47, P < 0.001; 6wk: F(5,80) = 53.61, P < 0.001; Figure 4(a1) to (c1)) and the number of errors (2wk: F(5,80) = 8.525, P < 0.001; 4wk: F(5,80)= 24.407, P < 0.001; 6wk: F(5,80) = 22.881, P < 0.001; Figure 4(a2) to (c2)), whereas the use of the spatial strategy progressively increased (2wk: F(5,80) = 13.354, P < 0.001; 4wk: F(5,75) = 10.318, P < 0.001; 6wk: F(5,80) = 9.226, P < 0.001; Figure 4(a3) to (c3)), indicating that all mice learned the task. At neither treatment-analysis interval, there was a main effect of CSD (2wk: F(1,80) = 3.654, P = 0.074; 4wk: F(1,80) = 2.4, P = 0.141; 6wk: F(1,80) = 0.003, P = 0.958) or a CSD × day interaction (2wk: F(5,80) = 0.68, P = 0.64; 4wk: F(5,80) = 1.578, P = 0.42; 6wk: F(5,80) = 1.006, P = 0.176) on total distance (Figure 4(a1) to(c1)). Similarly, we found no CSD × day interaction (2wk: F(5,80) = 0.84, P = 0.525; 4wk: F(5,80) = 1.75, P = 0.133; 6wk: F(5,80) = 1.023, P = 0.41) and no main effects of CSD for total errors, despite in the 4wk group (2wk: F(1,80) = 4.277, P = 0.055; 4wk: F(1,80) = 4.921, P = 0.0416; 6wk: F(1,80) = 0.002, P = 0.965; Figure 4(a2) to (c2)). Evaluation of spatial strategy use showed significant main effects of CSD in the 2wk and 4wk groups (2wk: F(5,80) = 8.038, P = 0.012; 4wk: F(5,75) = 10.134, P = 0.006; 6wk: F(5,80) = 1.462, P = 0.244; Figure 4(a3) to (c3)). Post hoc testing revealed significant impairments of CSD mice in the 2wk group in that they passed a longer distance on day 4 (P = 0.029) and made more errors on day 4 (P = 0.023) and day 5 (P = 0.043). In the 4wk group, CSD mice moved a shorter distance on day 4 (P = 0.035) and made less errors than sham animals during days 3 (P = 0.026) and 4 (P = 0.008), indicating improved learning due to CSD. Consistent with these findings, CSD animals used less spatial strategy than sham mice in the 2wk group on days 4 (P < 0.001) and 5 (P = 0.012), whereas in the 4wk group, their spatial strategy use outreached that of sham mice on days 2 (P = 0.045), 4 (P = 0.004), and 6 (P = 0.021). For neither parameter, we detected significant CSD effects in the 6wk group. The probe trial confirmed that all animals learned the task. All mice, independent of group or treatment-analysis delay, displayed significant differences in the number of pokes into different holes (P < 0.001; Friedman test) and a clear preference for the previous target position (P < 0.05; Wilcoxon; Figure 5(a) to (c)), except occasionally holes −1, −2, +1, or +2. Specific CSD effects on spatial memory could not be detected, neither for target preference, nor for primary latency (Figure 5(a1) to (c1)). During the control trial, when the escape box was moved again by 90°, the preference for the former target hole disappeared (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Time-dependent effects of CSD on spatial learning in the Barnes maze (BM). Animals were tested during the third (a–a3), fifths (b–b3) or seventh (c–c3) week after the induction of CSD. Spatial learning performance was evaluated from the distance covered (a1–c1) and errors made (a2–c2) to find the hidden goal box, as well as from the use of spatial strategies (a3–c3). All data presented as mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; 2-way RM-ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test.

Figure 5.

Assessment of spatial memory and potential contribution of non-spatial cues at one week after BM training. (a–c) The graphs illustrate the number of visits to the 20 holes during the probe trial (pt; target position shifted by 180° relative to acquisition phase; nT1) and the control trial (ct; target position shifted by 90°; nT2) in the 2 (a), 4 (b) and 6 (c) week groups. (a1–c1) illustrate the primary latency to the initial target position learned during task acquisition. Values represent mean ± SEM; Friedman-Test followed by Mann–Whitney or Wilcoxon test.

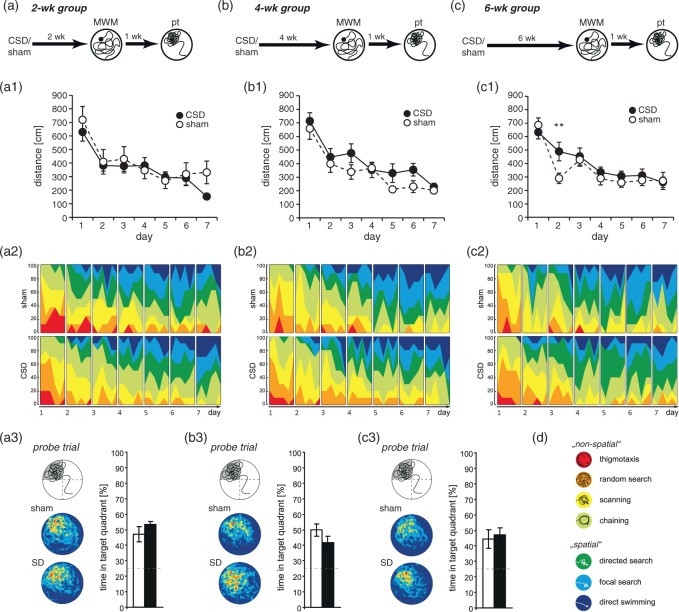

An independent cohort of mice was evaluated in a MWM and total distance was taken as quantitative measure of learning. As in the BM, all mice improved over the course of training (Figure 6(a1) to (c1); 2wk: F(6,96) = 13.426, P < 0.001; 4wk: F(6,96) = 19.644, P < 0.001; 6wk: F(6,96) = 22.90, P < 0.001; 2-way RM-ANOVA). Independent of the treatment-analysis interval, we found neither main effects of CSD (2wk: F(6,96) = 0.636, P = 0.437; 4wk: F(6,96) = 2.542, P = 0.130; 6wk: F(6,96) = 0.823, P = 0.378) nor CSD × day interactions (2wk: F(6,96) = 0.872, P = 0.518; 4wk: F(6,96) = 0.672, P = 0.673; 6wk: F(6,96) = 1.830, P = 0.101). Post hoc testing revealed significant CSD effects only for day 2 in the 6wk group (P = 0.006), the other groups showed no differences (Figure 6(a1) to (c1)). As distance has its limitations in reflecting subtle changes in spatial learning abilities, we qualitatively assessed the search paths by classifying them into seven mutually exclusive strategies.33 In all mice navigation initially relied predominantly on non-spatial, hippocampus-independent search strategies. With ongoing training, there was a progression towards more precise, spatial strategies (Figure 6(a2) to(c2), 6(d)). In the 2wk group, binary logistic regression analysis revealed that CSD mice used significantly more chaining (P = 0.006, GENLIN) over the course of training and specifically on days 3 (P < 0.001), 4 (P = 0.034), and 6 (P = 0.001; Figure 6(a2)). In the 4wk group, we found no general differences between CSD and sham animals, but CSD mice used less chaining on day 4 (P = 0.009) and less focal search on day 6 (P = 0.031; Figure 6(b2)). Analysis of the 6wk group revealed more overall use of random search (P = 0.046) and directed search (P = 0.03) in the CSD groups. Specifically, CSD mice used less scanning (P = 0.039) and more chaining (P = 0.031) on day 1, less chaining (P = 0.007) on day 2, less scanning (P = 0.030), more chaining (P = 0.003), and less focal search (P = 0.024) on day 5, more directed search (P = 0.024) and less focal search (P = 0.002) on day 6 and more directed search (P = 0.005) on day 7 (Figure 6(c2)). In the probe trial, all mice searched selectively, spending more time in the former target quadrant (P < 0.01, one-sample t-test; Figure 6(a3) to (c3)). Furthermore, there were no group-specific differences in this measure (2wk: P = 0.276, 4wk: P = 0.171, 2wk: P = 0.712; t-test). Thus, all mice remembered the previously learned escape location but CSD did not affect this kind of spatial memory.

Figure 6.

Time-dependent effects of CSD on spatial learning and memory in the Morris water maze. Animals were tested during the third (a–a3), fifths (b–b3), or seventh (c–c3) week after the induction of CSD. Spatial learning performance was evaluated from the distance covered to find the hidden platform (a1–c1) and from the classification of spatial strategies (a2–2). The color code for search strategies is shown in (d). (a3–c3) Spatial memory was assessed in a probe trial performed one week after the last training in which the platform was removed from the pool. The graphs show the mean time animals spent in the former target quadrant. The dashed lines indicate chance level (25%). Furthermore, the left panel of each figure shows the occupancy plots illustrating search accuracy. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; **P < 0.01; 2-way RM-ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test, or t-test.

To analyze the relationship between the number of CSD and dependent variables, we performed a Pearson correlation analysis. Similar to our previous studies on rats (unpublished data), we found no clear evidence for a correlation between the number of CSD and the number of newborn cells (separate analysis of CSD mice for each treatment-analysis interval, r2 ≤ 0.1, P > 0.05). We furthermore calculated the correlation between the number of CSD and LNR (exploration index), BM (AUC for distance during acquisition), and MWM performance (AUC for distance during acquisition) which revealed similar results (separate analysis of CSD mice for each treatment-analysis interval, r2 ≤ 0.3, P > 0.05).

Discussion

Since its original discovery by Aristides Leão, a large amount of research has been conducted into phenomenology, mechanisms, and clinical relevance of CSD.1,2,25 Most of these studies mainly focus on the acute events occurring at onset, during or shortly after a CSD, while investigations of long-term consequences are virtually lacking. Here, we induced CSD in mice and examined their impact on adult neurogenesis and on different aspects of hippocampus-dependent memory over a period of several weeks. As expected from our observations in rats,5 CSD induced a significant increase in DGC birth also in mice. Neuronal differentiation and long-term survival of newborn cells paralleled those of sham mice. Our results from behavioral experiments demonstrate for the first time that CSD entails lasting changes in psychomotor behaviors and complex, delay- and task-dependent changes in spatial memory. These findings suggest a possible involvement of CSD-like events in emotional and cognitive changes observed after associated brain pathologies like stroke or traumatic brain injury.35,36

We found that CSD is a potent stimulus for cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the ipsilateral DG. Although the precise mechanisms of how CSD convey their pro-neurogenic effects to the DG are unclear, some hypotheses can be drawn from previous studies. The main afferent input to the DG arises from neurons located in layer II of the ipsilateral entorhinal cortex.37,38 Activation of these afferents, e.g. by tetanic stimulation of the perforant path or by deep brain stimulation of the entorhinal cortex, increases DG neurogenesis to a similar extent as observed in the present study.39,40 In addition, neurotransmitters (e.g. glutamate) and neurotrophins (e.g. BDNF, possibly originating from entorhinal cortex) are likely involved in activity-driven regulation of neurogenesis.39,41,42 CSD in turn propagate through the entire ipsilateral cortex of rodents including the entorhinal cortex and lead to the release of glutamate and BDNF from neurons.4,43,44 Most importantly, ample evidence suggests that CSD activates the hippocampus and eventually changes its physiology: neocortical SD has been shown to increase c-Fos expression in ipsilateral DGCs and to enhance hippocampal long-term potentiation.4,45 Previous studies furthermore showed that, in vivo, CSD do not invade the hippocampus.5,45 Together, these findings suggest that CSD stimulates ipsilateral DG neurogenesis indirectly due to activation of the entorhinal cortex and perforant path fibers, which may eventually lead to the liberation of pro-neurogenic factors in the DG.

Beside the prominent ipsilateral stimulation of hippocampal neurogenesis, a mild increase was observed also in the contralateral DG of CSD mice (Supplementary Table 3). In the light of previous studies showing bilateral alterations of neuronal activity and functional connectivity, as well as a bilateral stimulation of cortical gliogenesis in response to unilateral CSD, this result of the present study was not entirely surprising.3,46,47 However, it remains unclear how exactly the pro-neurogenic signals of CSD are conferred to the contralateral DG. There are two routes connecting the DG directly with the contralateral hemisphere: first, a commissural projection mainly arising from hilar mossy cells in the contralateral DG and second, a weak projection emerging in the contralateral entorhinal cortex.37,38

The rate of neuronal differentiation was not changed by CSD, and nearly all newborn cells, including 22–27 days old ones, expressed the neuronal marker NeuN. This is consistent with earlier findings in healthy mice, showing that as early as one week after BrdU injection 91% of the newborn cells co-express NeuN.15 Furthermore, the present study revealed that the number of newborn DGCs does not decline beyond an age of two weeks, fitting to the concept that apoptosis of adult-born DGCs mostly occurs during the first days after their birth.48

Interestingly, our study reveals that MWM training, if commenced 6 weeks after CSD, leads to an additional increase in newborn cell numbers. Previous studies have shown that MWM learning has complex effects on adult-born cells in the DG, depending on their age at the time of learning; spatial learning promoted survival of cells born around one week before training, decreased the number of cells born just before onset of training and stimulated the proliferation of progenitor cells.49–52 Which of these mechanisms contribute to the increased number of IdU-labeled cells at six weeks after CSD remains elusive. A survival effect appears unlikely, as 5–6 week old neurons already passed the critical time window.13,51 Moreover, increased survival does not explain the rise in cell numbers from 2 to 6 weeks (as has been confirmed by the comparison with time-matched cage-control mice/non-learners; unpublished data). Hence, it appears most likely that MWM learning increases the number of IdU-positive cells by stimulating their proliferation. Although this hypothesis needs further investigation, one can assume that the fraction of IdU+/NeuN− cells (approx. 5%) may comprise early-stage progenitor cells that retained the potential to respond to learning.

Further studies have shown that the degree to which learning influences neurogenesis depends on the type and difficulty of the task.53,54 More challenging tasks, that require more training to learn, resulted in higher cell survival than tasks learned more quickly.54 In our study, asymptotic performance of mice was reached earlier in the BM than in the MWM. Thus, the contradictory effects of MWM and BM learning on the number of IdU-positive cells may probably result from differences in task difficulty.

Assessing non-mnemonic behavior in the OF revealed a sustained increase in locomotor activity after CSD. Such a phenotype lasting from days to several weeks was also observed following mild focal ischemia.55,56 This indicates that spreading depolarizations which propagate from the ischemic tissue to the surrounding, well supplied cortex25,57 may be involved in the induction of post-stroke hyperactivity. However, we detected no signs of anxiety that typically emerge after ischemia or traumatic brain injury.36,56

Through convincing evidence for a role of adult-born neurons in hippocampal function,10–12 we next assessed whether CSD affects hippocampus-dependent memory. We chose three tests of varying cognitive demand to assess place recognition (LNR) and reference memory (BM, MWM). The effects of CSD were clearly task-dependent. While place recognition was consistently improved independent of the delay between CSD and testing, BM learning was affected as a function of time: CSD impaired BM acquisition if the delay was two weeks, facilitated spatial memory formation with a delay of four weeks and had no effects at a six-week delay. In contrast, CSD effects on MWM acquisition were below the detection threshold of classical quantitative measures of MWM performance (i.e. distance, latency), confirming our previous findings in rats.5 Hence, we did a detailed analysis of swim paths that revealed subtle changes in the use of spatial strategies. The CSD-related differences not only manifested later than in the other two tests (earliest at a delay of 4–6 weeks) but also indicated a slight net impairment of CSD mice in the progression towards more spatially precise strategies (i.e. focal search). Such discrepancies in the sensitivity of behavioral tasks towards changes in hippocampal function have been observed earlier.58,59 While all three tasks applied in the present study are tests for spatial memory, they might be differentially prone to effects of CSD not directly affecting the hippocampus. Insofar, the LNR and BM rely on mice’s natural behaviors (i.e. novelty preference or seeking for shelter, respectively) and thus are less stressful and less exhausting than the MWM, in which mice have to locate a hidden escape by swimming in cold water.31,34 At the same time, BM performance might be confounded by changes in exploratory drive and anxiety, which is particularly relevant in the context of the present findings showing that CSD mice were more active in the OF. However, a general bias by the consistently increased exploratory activity of CSD mice appears unlikely to explain the distinct, delay-dependent outcomes in the BM.

It remains to be determined to what extent the observed behavioral changes are caused by the increase in adult neurogenesis. CSD produces a range of other effects that, in principle, could contribute to the observed changes in behavior. For example, it has widespread effects on cortical gene expression and leads to a striking increase in cortical gliogenesis, both lasting for several weeks.3,4 In addition, CSD is associated with a temporary distortion of dendritic structures and loss of dendritic spines which, especially after multiple recurrent CSD, may lead to long-term changes in cortical networks.60 Nevertheless, it is tempting to speculate about a correlation between the two observations, first, because adult-born neurons are involved in hippocampus-dependent memory10–12,42 and second, because the time course of CSD effects on BM learning obviously matches the stages of functional integration of newborn DGCs. Positive effects of CSD were observed around the time that immature DGCs undergo a phase of increased excitability and plasticity, and become activated during spatial memory recall (∼3–4 weeks of age at start of BM).7,8,17 Moreover, there were no more differences at the time when the new DGCs become stably integrated into the hippocampal circuitry (∼5–6 weeks of age).22 The finding that BM learning was impaired at two weeks after CSD was unexpected in the context of adult neurogenesis. In this experiment, new neurons were ∼1–2 weeks old when BM training commenced, an age at which they just start establishing first input/output contacts and cannot sufficiently pass information from entorhinal cortex to CA3.7,8,22,23 Studies using cytostatic drugs or irradiation to ablate proliferating cells from the adult DG suggested that such very young neurons are not required or even support hippocampus-dependent memory processes.15,18,20,58 However, a recent study by Akers et al.21 showed that, while actively integrating, adult-born neurons may promote the loss of recently acquired memories, putatively by competing with existing neurons for established synapses.24,61 Alternatively, the early impairments of CSD mice in BM acquisition might be related to the increased exploratory activity and decreased anxiety at this time, which could, similar to memory impairment, cause mice taking longer, less spatially directed paths.62

Despite the absence of correlation between newborn cell numbers, behavioral changes and the rate of CSD we would not conclude a general lack of a dose–response relationship. Rather, we assume that our finding is related to the relatively high number of CSD induced in the present study (7–13 CSD). A saturation limit is probably achieved with less than seven CSD, with more CSD not further changing cell proliferation or behavior. This assumption is supported by a previous report of Tamura et al.63 who found a correlation between CSD numbers and cortical gliogenesis if mildly stimulated rats (2–3 CSD) were compared to highly stimulated rats (10–18 CSD), whereas no such correlation was evident in the group of highly stimulated rats alone.

Together, our data show for the first time that CSD, which is a transient and largely benign phenomenon, has lasting but distinct and task-specific effects on non-mnemonic behavior and cognition. This finding implies that CSD might contribute to the neurobehavioral consequences of associated brain pathologies, like ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and traumatic brain injury. The mechanisms underlying the behavioral effects of CSD are not entirely clear, but amongst others may include the increase in adult neurogenesis. Furthermore, our data implicate that an excess of very young newborn DGCs far above the physiological level might even disrupt hippocampal memory processing. Future studies using mouse models to conditionally prevent the increase in adult-born DGCs are needed to assess the link between neurogenesis and the behavioral outcome after CSD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Anne Ansorg, Sindy Beck, Johanna Kliche and Beatrix Lippert for excellent technical assistance, and Christian Schmeer for careful language editing. We thank Alexander Garthe for providing the algorithm for strategy analysis.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for this project was provided by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, grant no. 01GI9905 and no. 01GZ0306), the German Research foundation (DFG, grant no. WI830/10-1), the Interdisciplinary Centre for Clinical Research (IZKF; grant no. J15) and the Leibniz Graduate School on Ageing and Age-Related Diseases (LGSA).

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contribution

AU conceived and designed the study, analyzed data, wrote the article, contributed reagents and materials; EB conducted experiments and analyzed data; FB conducted experiments and analyzed data; OW participated in study design, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, revised article.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this paper can be found at http://jcbfm.sagepub.com/content/by/supplemental-data

References

- 1.Lauritzen M, Dreier JP, Fabricius M, et al. Clinical relevance of cortical spreading depression in neurological disorders: migraine, malignant stroke, subarachnoid and intracranial hemorrhage, and traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011; 31: 17–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Somjen GG. Mechanisms of spreading depression and hypoxic spreading depression-like depolarization. Physiol Rev 2001; 81: 65–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urbach A, Brueckner J, Witte OW. Cortical spreading depolarization stimulates gliogenesis in the rat entorhinal cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2015; 35: 576–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urbach A, Bruehl C, Witte OW. Microarray-based long-term detection of genes differentially expressed after cortical spreading depression. Eur J Neurosci 2006; 24: 841–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urbach A, Redecker C, Witte OW. Induction of neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus by cortical spreading depression. Stroke 2008; 39: 3064–3072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eichenbaum H. A cortical-hippocampal system for declarative memory. Nat Rev Neurosci 2000; 1: 41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mongiat LA, Esposito MS, Lombardi G, et al. Reliable activation of immature neurons in the adult hippocampus. PLoS One 2009; 4: e5320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao C, Teng EM, Summers RG, Jr, et al. Distinct morphological stages of dentate granule neuron maturation in the adult mouse hippocampus. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 3–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drew LJ, Fusi S, Hen R. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian hippocampus: why the dentate gyrus? Learn Mem 2013; 20: 710–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng W, Aimone JB, Gage FH. New neurons and new memories: how does adult hippocampal neurogenesis affect learning and memory? Nat Rev Neurosci 2010; 11: 339–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mongiat LA, Schinder AF. Adult neurogenesis and the plasticity of the dentate gyrus network. Eur J Neurosci 2011; 33: 1055–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aimone JB, Deng W, Gage FH. Adult neurogenesis: integrating theories and separating functions. Trends Cogn Sci 2010; 14: 325–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain: significant answers and significant questions. Neuron 2011; 70: 687–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marin-Burgin A, Mongiat LA, Pardi MB, et al. Unique processing during a period of high excitation/inhibition balance in adult-born neurons. Science 2012; 335: 1238–1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snyder JS, Choe JS, Clifford MA, et al. Adult-born hippocampal neurons are more numerous, faster maturing, and more involved in behavior in rats than in mice. J Neurosci 2009; 29: 14484–14495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tashiro A, Makino H, Gage FH. Experience-specific functional modification of the dentate gyrus through adult neurogenesis: a critical period during an immature stage. J Neurosci 2007; 27: 3252–3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kee N, Teixeira CM, Wang AH, et al. Preferential incorporation of adult-generated granule cells into spatial memory networks in the dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci 2007; 10: 355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shors TJ, Miesegaes G, Beylin A, et al. Neurogenesis in the adult is involved in the formation of trace memories. Nature 2001; 410: 372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aasebo IE, Blankvoort S, Tashiro A. Critical maturational period of new neurons in adult dentate gyrus for their involvement in memory formation. Eur J Neurosci 2011; 33: 1094–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng W, Saxe MD, Gallina IS, et al. Adult-born hippocampal dentate granule cells undergoing maturation modulate learning and memory in the brain. J Neurosci 2009; 29: 13532–13542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akers KG, Martinez-Canabal A, Restivo L, et al. Hippocampal neurogenesis regulates forgetting during adulthood and infancy. Science 2014; 344: 598–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esposito MS, Piatti VC, Laplagne DA, et al. Neuronal differentiation in the adult hippocampus recapitulates embryonic development. J Neurosci 2005; 25: 10074–10086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toni N, Laplagne DA, Zhao C, et al. Neurons born in the adult dentate gyrus form functional synapses with target cells. Nat Neurosci 2008; 11: 901–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toni N, Teng EM, Bushong EA, et al. Synapse formation on neurons born in the adult hippocampus. Nat Neurosci 2007; 10: 727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dreier JP. The role of spreading depression, spreading depolarization and spreading ischemia in neurological disease. Nat Med 2011; 17: 439–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panakhova E, Buresova O, Bures J. Functional hemidecortication by spreading depression or by focal epileptic discharge disrupts spatial memory in rats. Behav Processes 1985; 10: 387–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deutsch JA. The Physiological basis of memory, 2nd edn Academic Press: New York, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bures J, Buresova O, Krivanek J. The mechanism and application of Leao’s spreading depression of electroencephalographic activity, New York, NY: Academic Press, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buresova O, Bures J. The effect of prolonged cortical spreading depression on consolidation of visual engrams in rats. Psychopharmacologia 1971; 20: 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buresova O, Bures J. The effect of prolonged cortical spreading depression on learning and memory in rats. J Neurobiol 1969; 1: 135–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mumby DG, Gaskin S, Glenn MJ, et al. Hippocampal damage and exploratory preferences in rats: memory for objects, places, and contexts. Learn Mem 2002; 9: 49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urbach A, Robakiewicz I, Baum E, et al. Cyclin D2 knockout mice with depleted adult neurogenesis learn Barnes maze task. Behav Neurosci 2013; 127: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garthe A, Behr J, Kempermann G. Adult-generated hippocampal neurons allow the flexible use of spatially precise learning strategies. PLoS One 2009; 4: e5464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrison FE, Hosseini AH, McDonald MP. Endogenous anxiety and stress responses in water maze and Barnes maze spatial memory tasks. Behav Brain Res 2009; 198: 247–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson RG. Neuropsychiatric consequences of stroke. Annu Rev Med 1997; 48: 217–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rabinowitz AR, Levin HS. Cognitive sequelae of traumatic brain injury. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2014; 37: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Groen T, Miettinen P, Kadish I. The entorhinal cortex of the mouse: organization of the projection to the hippocampal formation. Hippocampus 2003; 13: 133–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scharfman HE. The Dentate Gyrus: A comprehensive guide to structure function and clinical implications. Vol. 163, Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chun SK, Sun W, Park JJ, et al. Enhanced proliferation of progenitor cells following long-term potentiation induction in the rat dentate gyrus. Neurobiol Learn Mem 2006; 86: 322–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stone SS, Teixeira CM, Devito LM, et al. Stimulation of entorhinal cortex promotes adult neurogenesis and facilitates spatial memory. J Neurosci 2011; 31: 13469–13484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hallbergson A, Peterson LD and Peterson DA. BDNF gene delivery recruits endogenous entorhinal cortical progenitor cells and increases neurogenesis in downstream hippocampal dentate gyrus. In: Society for neuroscience. Washington, DC: Program No. 141.14. 2005 Abstract Viewer/Itinerary Planner, 2005.

- 42.Zhao C, Deng W, Gage FH. Mechanisms and functional implications of adult neurogenesis. Cell 2008; 132: 645–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawahara N, Croll SD, Wiegand SJ, et al. Cortical spreading depression induces long-term alterations of BDNF levels in cortex and hippocampus distinct from lesion effects: implications for ischemic tolerance. Neurosci Res 1997; 29: 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fabricius M, Jensen LH, Lauritzen M. Microdialysis of interstitial amino acids during spreading depression and anoxic depolarization in rat neocortex. Brain Res 1993; 612: 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wernsmann B, Pape HC, Speckmann EJ, et al. Effect of cortical spreading depression on synaptic transmission of rat hippocampal tissues. Eur J Neurosci 2006; 23: 1103–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li B, Zhou F, Luo Q, et al. Altered resting-state functional connectivity after cortical spreading depression in mice. Neuroimage 2012; 63: 1171–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Unekawa M, Tomita Y, Toriumi H, et al. Potassium-induced cortical spreading depression bilaterally suppresses the electroencephalogram but only ipsilaterally affects red blood cell velocity in intraparenchymal capillaries. J Neurosci Res 2013; 91: 578–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sierra A, Beccari S, Diaz-Aparicio I, et al. Surveillance, phagocytosis, and inflammation: how never-resting microglia influence adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Neural Plast 2014; 2014: 610343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ambrogini P, Cuppini R, Cuppini C, et al. Spatial learning affects immature granule cell survival in adult rat dentate gyrus. Neurosci Lett 2000; 286: 21–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dobrossy MD, Drapeau E, Aurousseau C, et al. Differential effects of learning on neurogenesis: learning increases or decreases the number of newly born cells depending on their birth date. Mol Psychiatry 2003; 8: 974–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Epp JR, Chow C, Galea LA. Hippocampus-dependent learning influences hippocampal neurogenesis. Front Neurosci 2013; 7: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Epp JR, Spritzer MD, Galea LA. Hippocampus-dependent learning promotes survival of new neurons in the dentate gyrus at a specific time during cell maturation. Neuroscience 2007; 149: 273–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Epp JR, Haack AK, Galea LA. Task difficulty in the Morris water task influences the survival of new neurons in the dentate gyrus. Hippocampus 2010; 20: 866–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Curlik DM, 2nd, Shors TJ. Learning increases the survival of newborn neurons provided that learning is difficult to achieve and successful. J Cogn Neurosci 2011; 23: 2159–2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Winter B, Juckel G, Viktorov I, et al. Anxious and hyperactive phenotype following brief ischemic episodes in mice. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 57: 1166–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kilic E, Kilic U, Bacigaluppi M, et al. Delayed melatonin administration promotes neuronal survival, neurogenesis and motor recovery, and attenuates hyperactivity and anxiety after mild focal cerebral ischemia in mice. J Pineal Res 2008; 45: 142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dreier JP, Reiffurth C. The stroke-migraine depolarization continuum. Neuron 2015; 86: 902–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Madsen TM, Kristjansen PE, Bolwig TG, et al. Arrested neuronal proliferation and impaired hippocampal function following fractionated brain irradiation in the adult rat. Neuroscience 2003; 119: 635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raber J, Rola R, LeFevour A, et al. Radiation-induced cognitive impairments are associated with changes in indicators of hippocampal neurogenesis. Radiat Res 2004; 162: 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takano T, Tian GF, Peng W, et al. Cortical spreading depression causes and coincides with tissue hypoxia. Nat Neurosci 2007; 10: 754–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yasuda M, Johnson-Venkatesh EM, Zhang H, et al. Multiple forms of activity-dependent competition refine hippocampal circuits in vivo. Neuron 2011; 70: 1128–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harrison FE, Reiserer RS, Tomarken AJ, et al. Spatial and nonspatial escape strategies in the Barnes maze. Learn Mem 2006; 13: 809–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tamura Y, Eguchi A, Jin G, et al. Cortical spreading depression shifts cell fate determination of progenitor cells in the adult cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2012; 32: 1879–1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.