Abstract

In eukaryotic cells, genes are interrupted by intervening sequences called introns. Introns are transcribed as part of a precursor RNA that is subsequently removed by splicing, giving rise to mature mRNA. However, introns are rarely found in bacteria. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans is a periodontal pathogen implicated in aggressive forms of periodontal disease. This organism has been shown to produce cytolethal distending toxin (CDT), which causes sensitive eukaryotic cells to become irreversibly blocked at the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. In this study, we report the presence of introns within the cdt gene of A. actinomycetemcomitans. By use of reverse transcription-PCR, cdt transcripts of 2.123, 1.572, and 0.882 kb (RTA1, RTA2, and RTA3, respectively) were detected. In contrast, a single 2.123-kb amplicon was obtained by PCR with the genomic DNA. Similar results were obtained when a plasmid carrying cdt was cloned into Escherichia coli. Sequence analysis of RTA1, RTA2, and RTA3 revealed that RTA1 had undergone splicing, giving rise to RTA2 and RTA3. Two exon-intron boundaries, or splice sites, were identified at positions 863 to 868 and 1553 to 1558 of RTA1. Site-directed and deletion mutation studies of the splice site sequence indicated that sequence conservation was important in order for accurate splicing to occur. The catalytic region of the cdt RNA was located within the cdtC gene. This 0.56-kb RNA behaved independently as a catalytically active RNA molecule (a ribozyme) in vitro, capable of splicing heterologous RNA in both cis and trans configurations.

Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans is an oral pathogen implicated in the pathogenesis of aggressive forms of periodontal disease (12, 41, 44). This gram-negative bacterium produces a wide range of virulence factors that enhance its capacity to cause periodontal destruction. These include collagenases, endotoxin, leukotoxin, and cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) (13). A. actinomycetemcomitans has also been associated with other human diseases, including endocarditis, meningitis, and osteomyelitis (14, 30).

CDT constitutes a family of genetically related bacterial protein toxins that are produced by a variety of gram-negative mucosal pathogens such as Escherichia coli (31), Shigella dysenteriae (29), Campylobacter jejuni (32), Haemophilus ducreyi (6), and A. actinomycetemcomitans (39). CDT causes sensitive eukaryotic cells to become irreversibly blocked at the G2/M phase of the cell cycle (5). Morphologically, intoxicated cells become distended to several times their normal size over 2 to 5 days, eventually leading to cell death (25, 39). The cdt locus of A. actinomycetemcomitans consists of cdtA, cdtB, and cdtC organized in an apparent operon (38). The gene products have molecular masses of 27, 30, and 20 kDa, respectively. The deduced amino acid sequences derived from the three cdt genes of A. actinomycetemcomitans are about 20 to 50% similar to those from E. coli, S. dysenteriae, and C. jejuni and >95% similar to those from H. ducreyi (33). Expression of all three genes is required for CDT activity. Individually, purified recombinant CdtA, CdtB, or CdtC does not exhibit toxic activity (39). However, the toxin subunits are able to interact with one another to form an active tripartite holotoxin that exhibits full cellular toxicity (21, 37). CdtB is the active subunit of CDT holotoxin (9) and is capable of causing cell cycle arrest when introduced into cells. The CdtB polypeptide exhibits striking pattern-specific homology to members of the DNase I protein family (10, 20). Information about the functions of the CdtA and CdtC subunits of A. actinomycetemcomitans is limited (22). Recombinant CdtA, which has similarities to the carbohydrate-binding domain of the ricin B subunit, binds to the surfaces of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (23). Additionally, this study reported that recombinant CdtC, when introduced into CHO cells, resulted in cellular distension and eventual death. The emerging model for CDT action predicts that CdtA, CdtB, and CdtC form a tripartite complex that facilitates the entry of CdtB into cells by endocytosis (7, 8).

Introns are rarely found in eubacteria. Eubacterial introns identified to date are found mostly in genes associated with conjugal transfer, for instance, Tn5397 of Clostridium difficile (28) and the relaxase gene (ltrb) of Lactobacillus lactis (27). More recently, protein-encoding genes of C. difficile and Bacillus anthracis have been reported to possess introns (2, 15). Bacterial introns typically belong to either group I or group II. These introns are usually self-splicing where cleavage-ligation reactions occur efficiently in the absence of proteins (18, 36). Group I and II introns share little homology at the primary sequence level. Instead, these introns are classified based on their secondary structures and splicing mechanisms (4, 26). The conserved secondary structure of group I introns consists of characteristic stem-loop pairings (P1 to P10) and four conserved sequence elements (P, Q, R, and S) which form the catalytic core of the intron (4). The secondary structure of group II introns consists of six helical domains (I to VI) emerging from a central domain (26). Mechanistically, splicing of group I introns is initiated by a nucleophilic attack of the 3′ OH group of an exogenous guanosine cofactor at the 5′ splice site, resulting in covalent attachment of the guanosine to the 5′ end of the intron and release of the 5′ exon. In the second step, the free 3′ OH of the 5′ exon attacks the 3′ splice site, forming a phosphodiester bond between the 5′ exon and the 3′ exon, and liberating the intron (4). The splicing mechanism of group II introns is similar to that of eukaryotic pre-mRNA. The first step involves nucleophilic attack at the 5′ splice site by the 2′ OH group of a conserved A residue located within the 3′ end of the intron. The reaction yields a lariat structure where the 5′ end of the intron is ligated to the A residue by a 2′→5′ phosphodiester bond. The second step involves the attack of the 3′ splice site by the free 3′ OH group of the 5′ exon, resulting in ligation of the 5′ and 3′ exons and release of the intron lariat (26).

In this study, we report the presence of intervening sequences (IVS), or introns, within the cdt gene of A. actinomycetemcomitans. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first description of the presence of introns not only within the cdt gene family but also in the genome of an oral bacterium. The characteristics of these novel introns are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

A. actinomycetemcomitans strains ATCC 33384 and ATCC 700685, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.), were grown in 3% tryptic soy broth (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.) supplemented with 0.6% yeast extract (Becton Dickinson) at 37°C with 5% CO2. E. coli was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) with aeration at 37°C. The pGEMT-easy vector (Promega, Madison, Wis.) was used as the cloning vector. Purified DNA fragments were cloned into the pGEMT-easy vector by ligation of the 3′-A overhang of the PCR product and the 5′-T overhang of the vector. E. coli JM 109 (Promega) was used for cloning. E. coli BL21pLysS (Invitrogen) was used as the host for in vitro RNA splicing studies. Ampicillin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was added to LB agar to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml for selection of recombinant clones.

DNA manipulations.

Restriction endonucleases, T4 DNA ligase, alkaline phosphatase, and the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.) and used as recommended by the manufacturer. PCR products were purified by using the QIAquick PCR purification system (QIAGEN, Valencia, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmid DNA was extracted by using a QIAprep plasmid kit (QIAGEN). E. coli was transformed by electroporation with a Gene Pulser apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). Electroporation was performed in a 0.1-cm electrocuvette (Bio-Rad) at 1.8 kV, with a pulse setting of 25 μF capacitance and 200 Ω resistance.

RNA isolation.

Total RNA was extracted from A. actinomycetemcomitans at pre-logarithmic, logarithmic, and stationary phases of bacterial growth. Overnight cultures of E. coli were diluted 1:100 and incubated at 37°C with aeration until early-logarithmic phase (optical density at 600 nm, 0.4). Transcription of the cloned gene was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was washed twice by using 1× phosphate-buffered saline. RNA was isolated by using RNAwiz (Ambion, Austin, Tex.) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

cDNA synthesis.

The sequences of primers used in this study are listed in Table 1. A schematic diagram showing the organization of the cdt gene and the locations of the primers is shown in Fig. 1a. Oligonucleotides were purchased from Proligos, Singapore. Prior to reverse transcription, RNA was treated with 2 U of DNase I (Ambion) at 37°C for 30 min. The reverse transcription reaction mixture consisted of 100 ng of DNase I-treated RNA, 20 pmol of a gene-specific primer, 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 40 U of an RNase inhibitor (Fermentas, Hanover, Md.), 200 U of RevertAid H Minus Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Fermentas), and 1× reaction buffer. The negative-control reaction mixture was prepared in the same manner without reverse transcriptase to ensure that the RNA samples were free from contaminating DNA. cDNA synthesis was carried out at 42°C for 1 h. Reverse transcriptase was denatured by heating at 70°C for 10 min prior to PCR.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequencea | Location |

|---|---|---|

| cdtAF | 5′-ATCTAAGGAGAGGTACAATGAAA | 643-665b |

| cdCR | 5′-TTAGCTACCCTGATTTCTCC | 2745-2765b |

| cdtBF | 5′-GCTAAGGAGTTTATATGCAATG | 1329-1350b |

| cdtBR | 5′-TTAGCGATCACGAACAAAACTA | 2173-2194b |

| SDM-2 | 5′-TATTATCGGGAGGACAAGGTGC | 1947-1518b |

| SDM-3 | 5′-GTGCGCCAATTATTATCGGGGGGGCAAGGTGCAG | 1487-1520b |

| cdtCR (PstI) | 5′-aaaCTGCAGTTAGCTACCCTGATTTCTCC | 2745-2765b |

| cdtCF (BglII) | 5′-ggaAGATCTGGAGAATACTATGAAAAAATATT | 2195-2217b |

| cdtAR (BglII) | 5′-tgaAGATCTTTAATTAACCGCTGTTGCTTCT | 1307-1328b |

| cdtAR | 5′-TTAATTAACCGCTGCTGTTGCTTCT | 1307-1328b |

| HX1 | 5′-GCGCCATTTGGTCACAAT | 777-794c |

| HX5R (BglII) | 5′-ggaAGATCTAAGTATCTACATTATTTGTAATGC | 1597-1620c |

| cdtCR2 | 5′-CACCGGTGGTCTTAAAATTTTA | 2723-2744b |

| cdtCR3 | 5′-TTGGCCCAAAAGGAGGTAATA | 2701-2721c |

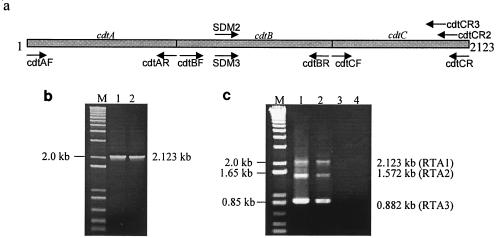

FIG. 1.

Analysis of cdt gene transcription using primers cdtAF and cdtCR. (a) Diagram showing the organization of the cdt genes. Arrows indicate the locations and orientations of the primers used. (b) Lanes 1 and 2, PCR results for the genomic DNAs of strains 33384 and 700685, respectively. (c) Lanes 1 and 2, RT-PCR amplicons of strains 33384 and 700685, respectively. Lanes 3 and 4, RT-PCR without reverse transcriptase of RNAs used in lanes 1 and 2. Lanes M, DNA size marker (1 Kb Plus; Invitrogen).

PCR.

All PCRs were performed by using a thermocycler (iCycler; Bio-Rad Laboratories) in a final volume of 50 μl. The PCR mixture consisted of 50 pmol of forward and reverse primers, 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 2 mM MgSO4, 2 U of Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs), 1× ThermoPol buffer, and 50 ng of DNA template. For reverse transcription-PCRs (RT-PCRs), one-fifth of the reverse transcription mixture was used as a template. Thermal cycle conditions consisted of denaturation at 94°C for 40 s, the optimal annealing temperature for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 2 min. After 30 cycles, the reaction was completed with a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. Following amplification, PCR products were placed on ice, and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega) was added, mixed well, and incubated at 72°C for 10 min to allow addition of the 3′ A-overhang. PCR products were analyzed on a 1% agarose gel.

DNA sequencing and analysis.

RT-PCR products were gel purified from SeaKem GTG agarose (FMC Bioproducts, Philadelphia, Pa.) by using a QIAquick gel purification system (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Purified products were cloned into the pGEMT-easy vector (Promega). Both sense and antisense strands were sequenced. Cycle sequencing was performed by using the BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing kit (version 3.1; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Amplified products were analyzed by using an ABI PRISM model 3100 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Sequence alignment was performed using MegAlign 5.05 (DNASTAR, Madison, Wis.).

In vitro transcription.

RNA was synthesized in vitro by using T7 RNA polymerase (Ambion). A linear PCR DNA template with T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequence upstream was used as a template for in vitro transcription. Radiolabeled and unlabeled transcripts were synthesized by using the Megascript (Ambion) in vitro transcription system according to the manufacturer's instructions. For synthesis of the labeled transcript, an additional 1 μl of [α-32P]rUTP (3,000 Ci/mmol; 10 mCi/ml) (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) was added to the reaction mixture. The RNA was purified by lithium chloride precipitation.

In vitro splicing assay.

Radiolabeled in vitro-transcribed cdt RNA was incubated in the presence of either group I or group II splicing buffers. For the group I intron splicing assay, the labeled RNA was heated at 95°C for 1 min and cooled in the presence of group I splicing buffer containing 100 mM NH4Cl, 100 mM MgCl2, and 50 mM HEPES (43). The reaction was initiated with GTP (Fermentas) to a final concentration of 0.1 mM, and the reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 60 min. For the group II intron splicing assay, the labeled transcripts were incubated at 45°C in 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM MgCl2, and 500 mM NH4Cl for 60 min (11). Reaction products were analyzed by using a 1% glyoxal gel (Ambion). Following electrophoresis, the gel was dried, and a sheet of X-ray film was laid on the gel and exposed in a cassette for 12 h at −70°C. After exposure, the film was developed and fixed.

trans-splicing assay.

In vitro-transcribed cdtC was incubated in the presence of A. actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin A (ltxA) RNA at 37°C for 1 h (16). The reaction mixture consisted of 100 ng of each RNA species in the presence of 1× in vitro transcription reaction buffer (Ambion) in a reaction volume of 10 μl.

SDM.

Site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) was performed by using the Gene Editor in vitro SDM system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sequences of the mutagenic oligonucleotides SDM-2 and SDM-3 can be found in Table 1. SDM mutants were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The cdtAF primer, together with either the cdtCR2 or the cdtCR3 reverse primer, was used to generate two 3′ splice site deletion mutants, W79 and W80.

Plasmid constructs.

A summary of plasmid constructs made in this study can be found in Table 2. All cloned fragments were sequenced to ensure that the cloned insert was inserted in the correct orientation. Primer pair cdtAF(RBS)-cdtCR was used to amplify the complete cdt gene. The PCR fragment was ligated to pGEMT-easy, and the resulting recombinant vector was designated pW78. For construction of pWAC, primer pair cdtAF-cdtAR (BglII) was used to amplify the cdtA gene with the BglII restriction site at the 3′ end. The purified PCR product was cloned into the pGEMT-easy vector, giving rise to pWA. The cdtC gene was amplified by using primer pair cdtCF (BglII)-cdtCR (PstI) and was inserted downstream of cdtA of pWA via the BglII and PstI sites of the insert and vector. Primer pairs cdtBF-cdtCR and cdtAF-cdtBR were used to amplify the cdtBC and cdtAB genes, respectively. A purified PCR product was cloned into the pGEMT-easy vector. The resulting recombinant plasmids were designated pWBC and pWAB, respectively. Primer pair HX1-HX5R (BglII) was used to amplify the leukotoxin A (ltxA) gene from the genomic DNA of A. actinomycetemcomitans by PCR. A purified PCR fragment was cloned into the pGEMT-easy vector to yield pHX. A cdtC fragment amplified by using primers cdtCF (BglII) and cdtCR (PstI) was cloned downstream of the ltxA gene of pHX via the BglII and PstI restriction sites of the gene and vector, giving rise to pHXC.

TABLE 2.

Summary of plasmid constructs

| Plasmid | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pGEMT-easy | Ampr; T7 RNA polymerase promoter upstream of MCSa | Promega |

| pW78 | pGEMT-easy containing 2.213-kb cdtABC genes | This study |

| pSDM-24 | SDM of pW78 with nucleotide A at position 867 bp | This study |

| pSDM-32 | SDM of pW78 with nucleotides GG at positions 867-868 bp | This study |

| pW79 | pGEMT-easy containing cdtABC genes with 21-nt deletion | This study |

| pW80 | pGEMT-easy containing cdtABC genes with 44-nt deletion | This study |

| pWA | pGEMT-easy containing the cdtA gene | This study |

| pWAC | pWA containing the cdtC gene | This study |

| pWBC | pGEMT-easy containing cdtBC genes | This study |

| pWAB | pGEMT-easy containing cdtAB genes | This study |

| pWHX | pGEMT-easy containing the ltxA gene | This study |

| pWHXC | pWHX containing the cdtC gene | This study |

MCS, multiple cloning sites.

Analysis of RNA structure.

RNA secondary structures were analyzed by using Mfold, version 3.1 (46).

RESULTS

Splicing of cdt in A. actinomycetemcomitans.

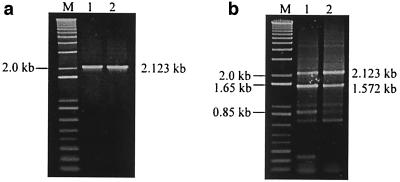

By using primer pair cdtAF-cdtCR, a single PCR product of 2.123 kb was obtained with genomic DNAs of A. actinomycetemcomitans 33384 and 700685 (Fig. 1b). Analysis of cdt transcripts by RT-PCR using the same primers gave three bands of 2.123 kb (RTA1), 1.572 kb (RTA2), and 0.882 kb (RTA3) (Fig. 1c). The control reaction in which reverse transcriptase was not added to the reaction mixture did not yield any amplicon (Fig. 1c), indicating that the RT-PCR products were derived from reverse transcription of cdt RNA and that there was no genomic DNA contamination in the RNA samples used.

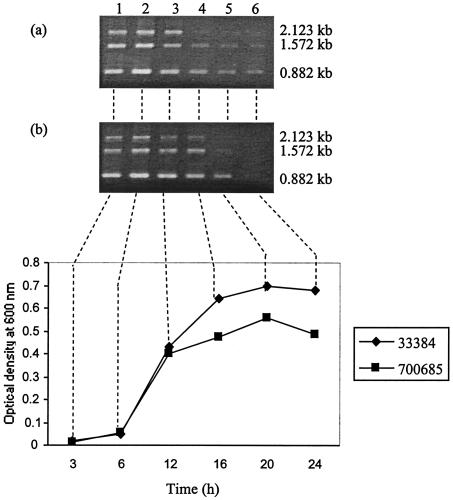

The growth profile of A. actinomycetemcomitans is shown in Fig. 2. RT-PCR analysis of RNAs extracted from 3-, 6-, 12-, 16-, 20-, and 24-h bacterial cultures of A. actinomycetemcomitans 33384 and 700685 using primer pair cdtAF-cdtCR gave three amplicons of 2.123, 1.572, and 0.882 kb (Fig. 2). As the bacteria approached the stationary phase of growth, the 2.123-kb cdt RNA was no longer detectable. The shorter cdt transcripts persisted until stationary phase for strain 700685. For strain 33384, no cdt transcripts were detected from a 24-h culture. Negative-control RT-PCRs of the RNA samples yielded no amplicons (data not shown). A single PCR band of 2.123 kb was obtained from cultures of different ages for both A. actinomycetemcomitans strains studied (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Time course analysis of cdt transcription. Graph shows the growth profiles of strains 33384 and 700685. RT-PCR using the primer pair cdtAF-cdtCR was performed on RNAs extracted from 3-, 6-, 12-, 16-, 20-, and 24-h cultures of A. actinomycetemcomitans. (a and b) Gel electrophoresis results for RT-PCR amplicons of strains 33384 and 700685, respectively.

Splicing of cdt in E. coli.

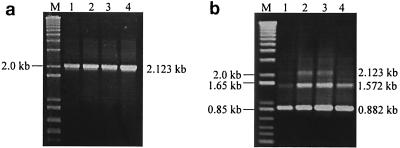

E. coli clone W78 possessed the complete cdt gene cloned downstream of the T7 RNA polymerase promoter of the pGEMT-easy vector. Transcription of cdt was induced by addition of IPTG. RT-PCR analysis of cultures at 1, 2, 3, and 4 h postinduction gave amplicons of 2.123, 1.572, and 0.882 kb (Fig. 3b). In contrast, PCR analysis of these cultures consistently gave a single 2.123-kb product (Fig. 3a). No PCR product was observed for the reaction without reverse transcriptase (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Analysis of cdt gene transcription in E. coli W78, carrying the cdt gene on a recombinant plasmid. Lanes 1 to 4, amplicons obtained from PCR (a) and RT-PCR (b) from cultures at 1 to 4 h postinduction, respectively, by using the primer pair cdtAF-cdtCR. Lanes M, DNA size marker.

Splice site specificity and usage.

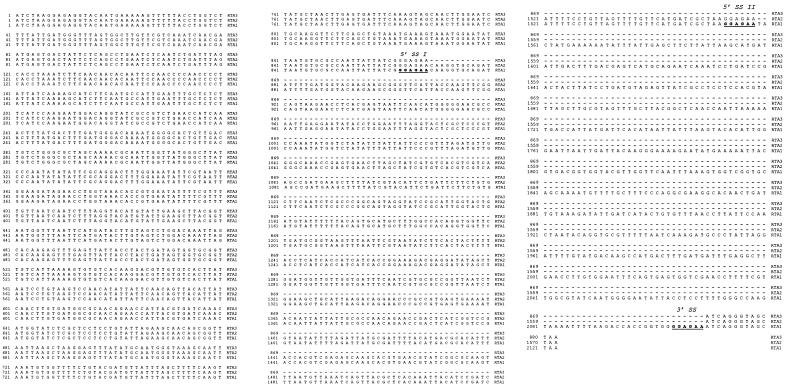

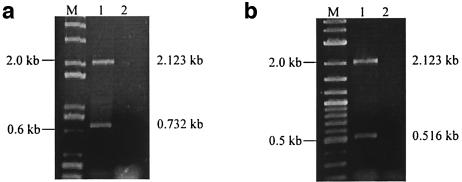

A sequence alignment of the full-length (RTA1) and spliced (RTA2 and RTA3) products of A. actinomycetemcomitans 700685 is shown in Fig. 4. Comparison of the nucleotide sequences of the full-length and spliced transcripts revealed the junctions between the exons and introns, or splice sites. The spliced products RTA2 and RTA3 shared a common 3′ exon but possessed different 5′ exons. The 5′ splice sites were found to be located at positions 863 to 868 and 1553 to 1558. Both 5′ splice sites possessed the hexanucleotide sequence GGA GAA. The 3′ splice site was located at positions 2104 to 2109. The full-length and spliced transcripts possessed ribosome-binding sites upstream. SDM of 5′ splice site I was performed to determine the effect(s) that sequence mutations at the conserved splice site had on splicing. Mutant SDM-24 had a single nucleotide change at position 867, with the nucleotide G instead of A. Mutant SDM-32 had a 2-nucleotide (2-nt) change at positions 867 and 868, with GG instead of AA. PCR amplicons of 2.123 kb were obtained from plasmid DNA of mutants SDM-24 and SDM-32 (Fig. 5a). SDM did not abolish the splicing activity of cdt RNA. Multiple RT-PCR bands were obtained from SDM-24 and SDM-32 (Fig. 5b). Amplicons of 2.123 and 1.572 kb were present in greater amounts than the other RT-PCR products, as estimated from the intensities of RT-PCR products. These RT-PCR products were similar to RTA1 and RTA2 (data not shown). The 0.882-kb spliced product of SDM-24 was present in amounts visibly less than those of the wild-type E. coli clone W78. SDM-32 did not possess any visible RT-PCR band at the 0.882-kb region. No band was observed for reactions without reverse transcriptase.

FIG. 4.

Sequence alignment of full-length (RTA1) and spliced (RTA2 and RTA3) transcripts. Exon-intron boundaries, or splice sites (SS), are underlined and boldfaced.

FIG. 5.

Effects of mutated 5′ splice site I on splicing activity. Lanes 1 and 2, PCR (a) and RT-PCR (b) amplicons of SDM-24 and SDM-32, respectively. Lanes M, DNA size marker.

In the absence of the 3′ splice site, the splicing abilities of mutants W79 and W80 were not abolished. PCR of the plasmid DNAs of these mutants gave bands of the expected sizes (data not shown). Mutant W79 gave two RT-PCR amplicons of 2.123 and 0.732 kb (Fig. 6a). Sequence analysis of the full-length and spliced products of this mutant indicated that splicing had occurred at an upstream cryptic splice site with the sequence GTA AA located at positions 2080 to 2084 (Fig. 6c). Mutant W80, which possessed deletions to both native and cryptic splice sites, gave two RT-PCR amplicons (Fig. 6b). Sequence analysis of these amplicons revealed that splicing occurred at another cryptic splice site with the sequence TAT TAC CT, located at positions 2059 to 2066 (Fig. 6c).

FIG. 6.

Deletion of 3′ splice site results in activation of cryptic splice sites. (a) Lane M, DNA size marker (1 Kb Plus). Lane 1, RT-PCR products of mutant W79. (b) Lane M, DNA size marker (2-Log Ladder; New England Biolabs). Lane 1, RT-PCR products of mutant W80. Lanes 2, negative-control RT-PCRs. (c) Sequences of wild-type and cryptic splice sites are underlined. Determination of the locations of the 3′ splice sites is dependent on a 20- to 24-nt proximity (upstream) to the 3′ exon.

Group I and II intron splicing assay.

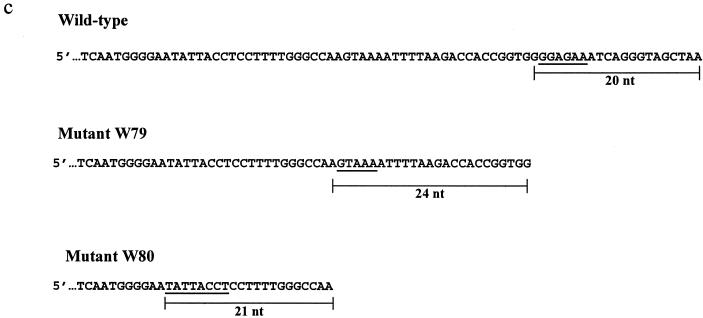

Cleavage at 5′ splice sites I and II would result in the excision of introns of approximately 1.2 and 0.6 kb, respectively. These introns were designated AacdtIVS-1 and AacdtIVS-2, respectively. AacdtIVS-1 and AacdtIVS-2 did not possess the P (AAUUNCNNGAAN), Q (AAUNNGNAGC), R (GUUCAGAGACUANA), and S (AAGAUAUAGUCC) conserved sequence elements that are characteristic of group I introns (3). Group II introns are most easily recognized through the reverse transcriptase encoded by an open reading frame within the intron (19). However, protein-protein BLAST (blastp) performed on AacdtIVS-1 and AacdtIVS-2 showed no similarity with known reverse transcriptases (data not shown). Additionally, the secondary structure of these introns did not resemble that of group II introns, where six helical domains emerge around a central domain (data not shown). We further examined the self-splicing abilities of AacdtIVS-1 and AacdtIVS-2 by incubating radiolabeled cdt RNA under conditions under which group I and II introns typically splice. An in vitro splicing assay failed to give rise to any spliced product (Fig. 7). Based on our results, it is unlikely that AacdtIVS-1 and AacdtIVS-2 belong to group I or II introns. Recently, the p44-1 IVS of Anaplasma phagocytophilum (the causative agent of the tick-borne disease human granulocytic ehrlichiosis) was reported to self-splice in vitro but to be structurally and mechanistically dissimilar to group I and II introns (45). Based on these findings, the authors suggested that p44-1 IVS could belong to a new group of bacterial introns.

FIG. 7.

Group I and group II intron splicing assays. Radiolabeled cdt RNA was incubated in the presence of group I (a) and group II (b) intron-splicing buffers. Lanes 1, 0 min after incubation; lanes 2, 60 min after incubation.

cdtC RNA is catalytically active.

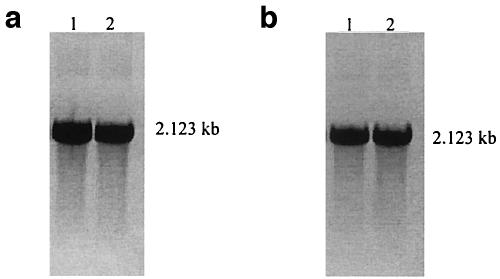

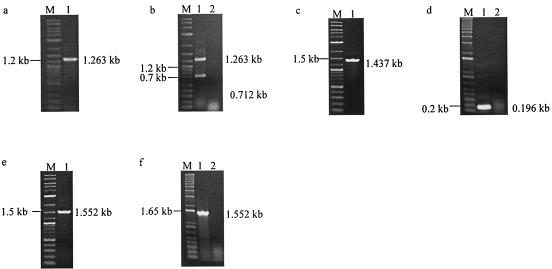

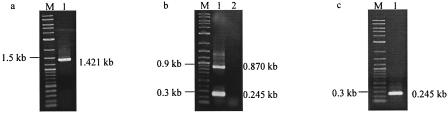

A series of clones with deletions of either cdtA, cdtB, or cdtC was constructed to determine the catalytic region of cdt RNA. Clone WAC, which lacked cdtB, gave the desired PCR band of 1.263 kb. However, two RT-PCR bands of 1.263 and 0.712 kb were obtained. Clone WBC, which possessed a deletion of the entire cdtA gene, gave the desired 1.437-kb PCR band. In contrast, a distinct 0.196-kb RT-PCR band was obtained. Clone WAB gave 1.552-kb PCR and RT-PCR bands, indicating that no splicing had occurred (Fig. 8). These results suggested that the catalytic sequence of cdt resides within cdtC. A fusion construct of ltxA and cdtC (pWHXC) was engineered to determine if cdtC alone could function as a catalytically active ribozyme. This clone gave the desired 1.421-kb amplicon PCR band, while three bands of 1.421, 0.870, and 0.245 kb were obtained by RT-PCR (Fig. 9a and b). In addition, cdtC was found to be capable of splicing ltxA RNA intermolecularly, in the trans configuration (Fig. 9c).

FIG. 8.

Transcription analysis was carried out on a series of clones with deletions of either cdtB (clone WAC), cdtA (clone WBC), or cdtC (clone WAB) to determine the location of the catalytic region of the cdt RNA. (a, c, and e) Lanes 1, PCR products of clones WAC, WBC, and WAB, respectively. (b, d, and f) Lanes 1, RT-PCR products of clones WAC, WBC, and WAB, respectively. Lanes 2, negative-control RT-PCRs without reverse transcriptase. Lanes M, DNA size marker.

FIG. 9.

Demonstration of the cis- and trans-splicing abilities of cdtC RNA. Transcription analysis of E. coli clone WHXC, possessing a fusion construct of ltxA and cdtC, was performed to show that cdtC RNA alone is catalytically active. (a and b) Lanes 1, PCR (a) and RT-PCR (b) products of E. coli clone WHXC. Lane 2, negative-control RT-PCR. (c) In vitro-transcribed cdtC RNAs were incubated in the presence of ltxA. Lanes M, DNA size marker.

DISCUSSION

During the study of the transcription of the cdt gene of A. actinomycetemcomitans, we discovered that the cdt transcript possesses IVS, or introns, that are removed from the precursor RNA by splicing. By RT-PCR, in vivo splicing of cdt was demonstrated in A. actinomycetemcomitans strains 33384 (serotype c) and 700685 (serotype b) and in E. coli. Sequence alignment of the full-length and spliced transcripts revealed the positions of exon-intron boundaries, or splice sites (Fig. 4). The 5′ splice sites were located at positions 863 to 868 and 1553 to 1558, both with the hexanucleotide sequence GGA GAA. The conserved nature of this sequence at both splice sites was intriguing. Mutations introduced at the splice site of Tetrahymena pre-rRNA resulted in the abolishment of splicing activity (35). In contrast, mutations introduced at 5′ splice site I of cdt did not abolish splicing function (Fig. 5). Instead, mutation of the splice site sequence resulted in a lower efficiency of splicing at the mutated site. Some splicing occurred at the 5′ splice site I of SDM-24, which contains a single base change to the site. When a 2-nt substitution was introduced at 5′ splice site I, as in SDM-32, splicing occurred exclusively at 5′ splice site II, the alternative site with the consensus sequence GGA GAA present in the cdt gene. Thus, conservation of the splice site sequence of cdt in A. actinomycetemcomitans is important for splicing to occur efficiently in vivo.

The 5′ splice sites of all group I introns identified to date share sequence and structure similarities. Splicing always occurred at the conserved “wobble” U-G base pair in the first stem-loop (P1) of the introns. Replacement of the consensus U-G with U-A, U-U, G-G, or A-G resulted in decreased splicing activity (1). Deletion of the 3′ splice site of cdt RNA did not abolish splicing function but resulted in activation of a cryptic splice site 24 nt upstream of the native 3′ splice site. The cryptic splice site of cdt possessed the sequence GTA AA, which shows some similarity to the original splice site sequence. However, mutant W80, which possessed deletions to both the native and cryptic splice sites, spliced at another cryptic splice site with the sequence TAT TAC CT, located 45 nt upstream of the original 3′ splice site. It is noteworthy that a cryptic splice site was used only in the absence of the normal site, never in its presence. In the absence of the native splice site sequence, splicing at cryptic sites can occur. In general, cryptic splice sites that are activated possess sequence similarity to the original sequence (34). Comparison between the authentic and cryptic splice site sequences did not reveal much similarity. Instead, it was observed that determination of cryptic splice site activation was dependent on a location 20 to 24 nt upstream from the end of the 3′ exon (Fig. 6c). Based on these observations, it appears possible for us to create a whole new set of “RNA restriction endonucleases” that may be used for sequence-specific cleavage of RNA by modifying the nucleotide sequences within the 3′ exon of the cdt ribozyme.

Deletion analysis was used to identify regions in cdt RNA that are essential for splicing and those that are dispensable. CdtB possesses endonuclease activity capable of nicking a supercoiled plasmid in vitro (10). Additionally, computational analysis of the amino acid sequence of CdtB using the Conserved Domain Database revealed similarity to a predicted RNA nuclease of Schizosaccharomyces pombe (24). Thus, the catalytic region of the cdt RNA was thought to reside within cdtB. However, in the absence of the cdtB gene, splicing of cdt occurred, indicating that that cdtB is dispensable and is not required for splicing. Splicing of cdt RNA was also unaffected in the absence of cdtA. In contrast, clone WAB, which lacks the cdtC gene, was found to be deficient in splicing, suggesting that the catalytically active part of cdt RNA resides within cdtC. Nevertheless, cdtA and cdtB sequences could be required to assist the folding of cdtC RNA into a catalytically active structure, since the activity of an RNA molecule resides in its ability to fold into a specific three-dimensional conformation (43). However, cdtC RNA was able to catalyze splicing of ltxA RNA (a heterologous RNA) in both the cis and trans configurations. These results indicate that cdtC RNA alone is a catalytically active ribozyme. Generally, in vivo splicing is an intramolecular reaction where only sequences on the same RNA molecule can be spliced out. In contrast, trans-splicing refers to the joining of exons found on different RNA molecules. This RNA processing mechanism can be found in lower eukaryotic cells such as trypanosomes, nematodes, and Euglena (17, 40, 42). This involves an interaction between a 5′ splice site present in the spliced leader RNA and a 3′ splice site located near the 5′ end of the pre-mRNAs. More recently, it was reported that viral-cellular hybrid mRNA molecules could be generated in mammalian cells by trans-splicing (3). Since cdtC RNA has the ability to trans-splice in vitro, we speculate that trans-splicing probably occurs within A. actinomycetemcomitans, producing a new combination of RNA species and thus increasing the coding capacity of genes.

Genes encoding endonucleases can often be found within group I introns (19). These endonucleases function in intron mobility; they initiate mobility by recognizing the intron insertion site within an intronless allele, followed by introduction of a DNA double-strand break near that site. A subsequent double-stranded break and repair mechanism using an intron-containing allele as a template leads to insertion of the intron into the target site by gene conversion. This process is called intron homing, because the intron usually inserts into the identical location in an intronless recipient allele. Although AacdtIVS-1 and AacdtIVS-2 do not possess structures and elements characteristic of group I introns, these introns possess a cdtB gene that, coincidentally, possesses endonuclease function (10). Whether CdtB functions as a homing endonuclease facilitating intron mobility in A. actinomycetemcomitans awaits future studies.

The function of introns within protein-encoding genes of eubacteria remains unknown. Intervening sequences found in the tcdA and recA genes of C. difficile and B. anthracis, respectively, are removed from their precursor mRNAs, giving rise to proteins that are functionally indistinguishable from their intronless counterparts (2, 15). More recently, bacterial RNA splicing was shown to function in a temperature-dependent fashion, as a novel means of regulating the expression of the major outer membrane protein gene (p44-18) of A. phagocytophilum (45). In this light, splicing of the cdt transcripts could serve as an avenue for posttranscriptional control, regulating the expression of Cdt proteins. We are currently investigating the roles of introns and RNA splicing of A. actinomycetemcomitans cdt in association with health and disease.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant NMRC/0545/2001 from the National Medical Research Council, Singapore, and Academic Research grant R-222-000-012-112 from the National University of Singapore.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barfod, E. T., and T. R. Cech. 1989. The conserved U · G pair in the 5′ splice site duplex of a group I intron is required in the first but not the second step of self-splicing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9:3657-3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun, V., M. Mehlig, M. Moos, M. Rupnik, B. Kalt, D. E. Mahony, and C. von Eichel-Streiber. 2000. A chimeric ribozyme in Clostridium difficile combines features of group I introns and insertion elements. Mol. Microbiol. 36:1447-1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caudevilla, C., L. D. Silva-Azevedo, B. Berg, E. Guhl, M. Graessmann, and A. Graessmann. 2001. Heterologous HIV-nef mRNA trans-splicing: a new principle how mammalian cells generate hybrid mRNA and protein molecules. FEBS Lett. 507:269-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cech, T. R. 1990. Self-splicing of group I introns. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 59:543-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comayras, C., C. Tasca, S. Y. Peres, B. Ducommun, E. Oswald, and J. De Rycke. 1997. Escherichia coli cytolethal distending toxin blocks the HeLa cell cycle at the G2/M transition by preventing cdc2 protein kinase dephosphorylation and activation. Infect. Immun. 65:5088-5095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cope, L. D., S. Lumbley, J. L. Latimer, J. Klesney-Tait, M. K. Stevens, L. S. Johnson, M. Purven, R. S. Munson, Jr., T. Lagergard, J. D. Radolf, and E. J. Hansen. 1997. A diffusible cytotoxin of Haemophilus ducreyi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:4056-4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cortes-Bratti, X., E. Chaves-Olarte, T. Lagergard, and M. Thelestam. 2000. Cellular internalization of cytolethal distending toxin from Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect. Immun. 68:6903-6911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deng, K., and E. J. Hansen. 2003. A CdtA-CdtC complex can block killing of HeLa cells by Haemophilus ducreyi cytolethal distending toxin. Infect. Immun. 71:6633-6640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elwell, C., K. Chao, K. Patel, and L. Dreyfus. 2001. Escherichia coli CdtB mediates cytolethal distending toxin cell cycle arrest. Infect. Immun. 69:3418-3422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elwell, C. A., and L. A. Dreyfus. 2000. DNase I homologous residues in CdtB are critical for cytolethal distending toxin-mediated cell cycle arrest. Mol. Microbiol. 37:952-963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferat, J. L., and F. Michel. 1993. Group II self-splicing introns in bacteria. Nature 364:358-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haffajee, A. D., and S. S. Socransky. 1994. Microbial etiological agents of destructive periodontal diseases. Periodontol. 2000 5:78-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henderson, B., S. P. Nair, J. M. Ward, and M. Wilson. 2003. Molecular pathogenicity of the oral opportunistic pathogen Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:29-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofstad, T., and A. Stallemo. 1981. Subacute bacterial endocarditis due to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 13:78-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ko, M., H. Choi, and C. Park. 2002. Group I self-splicing intron in the recA gene of Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 184:3917-3922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraig, E., T. Dailey, and D. Kolodrubetz. 1990. Nucleotide sequence of the leukotoxin gene from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: homology to the alpha-hemolysin/leukotoxin gene family. Infect. Immun. 58:920-929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krause, M., and D. Hirsh. 1987. A trans-spliced leader sequence on actin mRNA in C. elegans. Cell 49:753-761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kruger, K., P. J. Grabowski, A. J. Zaug, J. Sands, D. E. Gottschling, and T. R. Cech. 1982. Self-splicing RNA: autoexcision and autocyclization of the ribosomal RNA intervening sequence of Tetrahymena. Cell 31:147-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambowitz, A. M., and M. Belfort. 1993. Introns as mobile genetic elements. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 62:587-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lara-Tejero, M., and J. E. Galán. 2000. A bacterial toxin that controls cell cycle progression as a deoxyribonuclease I-like protein. Science 290:354-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lara-Tejero, M., and J. E. Galán. 2001. CdtA, CdtB, and CdtC form a tripartite complex that is required for cytolethal distending toxin activity. Infect. Immun. 69:4358-4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, R. B., D. C. Hassane, D. L. Cottle, and C. L. Pickett. 2003. Interactions of Campylobacter jejuni cytolethal distending toxin subunits CdtA and CdtC with HeLa cells. Infect. Immun. 71:4883-4890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mao, X., and J. M. DiRienzo. 2002. Functional studies of the recombinant subunits of a cytolethal distending holotoxin. Cell. Microbiol. 4:245-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marchler-Bauer, A., A. R. Panchenko, B. A. Shoemaker, P. A. Thiessen, L. Y. Geer, and S. H. Bryant. 2002. CDD: a database of conserved domain alignments with links to domain three-dimensional structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:281-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayer, M. P., L. C. Bueno, E. J. Hansen, and J. M. DiRienzo. 1999. Identification of a cytolethal distending toxin gene locus and features of a virulence-associated region in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect. Immun. 67:1227-1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michel, F., and J. L. Ferat. 1995. Structure and activities of group II introns. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64:435-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mills, D. A., L. L. McKay, and G. M. Dunny. 1996. Splicing of a group II intron involved in the conjugative transfer of pRS01 in lactococci. J. Bacteriol. 178:3531-3538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mullany, P., M. Pallen, M. Wilks, J. R. Stephen, and S. Tabaqchali. 1996. A group II intron in a conjugative transposon from the gram-positive bacterium Clostridium difficile. Gene 174:145-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okuda, J., H. Kurazono, and Y. Takeda. 1995. Distribution of the cytolethal distending toxin A gene (cdtA) among species of Shigella and Vibrio, and cloning and sequencing of the cdt gene from Shigella dysenteriae. Microb. Pathog. 18:167-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel, P. K., and M. W. Seitchick. 1986. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: a new cause for granuloma of the parotid gland and buccal space. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 77:476-478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pickett, C. L., D. L. Cottle, E. C. Pesci, and G. Bikah. 1994. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the Escherichia coli cytolethal distending toxin genes. Infect. Immun. 62:1046-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pickett, C. L., E. C. Pesci, D. L. Cottle, G. Russell, A. N. Erdem, and H. Zeytin. 1996. Prevalence of cytolethal distending toxin production in Campylobacter jejuni and relatedness of Campylobacter sp. cdtB gene. Infect. Immun. 64:2070-2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pickett, C. L., and C. A. Whitehouse. 1999. The cytolethal distending toxin family. Trends Microbiol. 7:292-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Price, J. V., J. Engberg, and T. R. Cech. 1987. 5′ exon requirement for self-splicing of the Tetrahymena thermophila pre-ribosomal RNA and identification of a cryptic 5′ splice site in the 3′ exon. J. Mol. Biol. 196:49-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Price, J. V., and T. R. Cech. 1988. Determinants of the 3′ splice site for self-splicing of the Tetrahymena pre-rRNA. Genes Dev. 2:1439-1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saldanha, R. G., M. Mohr, M. Belfort, and A. M. Lambowitz. 1993. Group I and group II introns. FASEB J. 7:15-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shenker, B. J., D. Besack, T. McKay, L. Pankoski, A. Zekavat, and D. R. Demuth. 2004. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans cytolethal distending toxin (Cdt): evidence that the holotoxin is composed of three subunits: CdtA, CdtB, and CdtC. J. Immunol. 172:410-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shenker, B. J., R. H. Hoffmaster, T. L. McKay, and D. R. Demuth. 2000. Expression of the cytolethal distending toxin (Cdt) operon in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: evidence that the CdtB protein is responsible for G2 arrest of the cell cycle in human T cells. J. Immunol. 165:2612-2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sugai, M., T. Kawamoto, S. Y. Peres, Y. Ueno, H. Komatsuzawa, T. Fujiwara, H. Kurihara, H. Suginaka, and E. Oswald. 1998. The cell cycle-specific growth-inhibitory factor produced by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans is a cytolethal distending toxin. Infect. Immun. 66:5008-5019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sutton, R. E., and J. C. Boothroyd. 1986. Evidence for trans splicing in trypanosomes. Cell 47:527-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan, K. S., K. P. Song, and G. Ong. 2002. Cytolethal-distending toxin of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: occurrence and association with periodontal disease. J. Periodontal Res. 37:268-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tessier, L. H., M. Keller, R. Chan, R. Fournier, J. H. Weil, and P. Imbault. 1991. Short leader sequences may be transferred from small RNAs to premature mRNAs by trans-splicing in Euglena. EMBO J. 10:2621-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woodson, S. A. 1992. Exon sequences distant from the splice junction are required for efficient self-splicing of the Tetrahymena IVS. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:4027-4032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zambon, J. J. 1985. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in human periodontal disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 12:1-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhi, N., N. Ohashi, and Y. Rikihisa. 2002. Activation of a p44 pseudogene in Anaplasma phagocytophila by bacterial RNA splicing: a novel mechanism for posttranscriptional regulation of a multigene family encoding immunodominant major outer membrane proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 46:135-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zuker, M. 2003. Mfold Web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3406-3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]