Abstract

Objectives

Nonmedical use of opioids during pregnancy is associated with adverse outcomes for women and infants, making it a prominent target for prevention and identification. Using a nationally representative sample, we determined characteristics of US pregnant women who reported prescription opioid misuse in the past year or during the past month.

Methods

We used data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (2005–2014) in a retrospective analysis. The sample included 8,721 (weighted N=23,855,041) non-institutionalized women, ages 12–44, who reported being pregnant when surveyed. Outcomes were nonmedical use of prescription opioid medications during the past 12 months and during the past 30 days. Multivariable logistic models were created to determine correlates of nonmedical opioid use after accounting for potential confounding variables.

Results

Among pregnant women in the US, 5.1% reported nonmedical opioid use in the past year. In adjusted models, depression or anxiety in the past year was strongly associated with past year nonmedical use (AOR=2.15 [1.52,3.04]), as were past year use of alcohol (AOR=1.56 [1.11,2.17]), tobacco (AOR 1.72 [1.17,2.53]), and marijuana (AOR 3.44 [2.47,4.81]).

Additionally, 0.9% of US pregnant women reported nonmedical opioid use in the past month. Past year depression or anxiety and past month use of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana each independently predicted past month nonmedical use.

Conclusions

Characteristics associated with nonmedical opioid use by pregnant women reveal populations with mental illness and co-occurring substance use. Policy and prevention efforts to improve screening and treatment could focus on the at-risk populations identified in this study.

INTRODUCTION

Over the last decade, prescription opioid use for nonmedical purposes during pregnancy nearly doubled.(Pan & Yi, 2013; Patrick et al., 2015) More than 20% of Medicaid beneficiaries filled an opioid prescription during pregnancy, with substantial and growing implications for the health of women and infants.(Desai, Hernandez-Diaz, Bateman, & Huybrechts, 2014) Nonmedical opioid use and associated conditions, including opioid dependence, can heighten the risk for pregnancy complications and birth defects.(ACOG Committee Opinion No. 524, 2012; Desai et al., 2015) In a recent national study, approximately 22% of women who reported past year nonmedical opioid use also met diagnostic criteria for opioid use disorder,(Saha et al., 2016) which carries heightened negative consequences generally and during pregnancy. Opioid dependency may place a pregnant woman at greater risk of experiencing violence, illness (such as Hepatitis C, HIV, or other sexually transmitted infections), as well as other high risk behaviors.(ACOG Committee Opinion No. 524, 2012; Krans & Patrick, 2016) Chronic nonmedical opioid use in pregnancy is associated with increased risk of newborn withdrawal, known as neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), and preterm birth, the largest contributor to infant mortality.(Kramer et al., 2000; Patrick et al., 2015) While not all infants exposed to opioids develop NAS,(Patrick et al., 2015) those who do have longer, more complicated birth hospitalizations with clinical signs that range from feeding difficulty to seizures.(Creanga et al., 2012; De’Souza, 2015; Patrick et al., 2012; Tolia et al., 2015) As the opioid epidemic has impacted more pregnant women, there has been a concomitant rise in the number of infants diagnosed with the syndrome. From 2000 to 2012, the national NAS rate increased from 1.2 to 5.8 per 1000 live hospital births, resulting an estimated $1.5 billion in hospital charges.(Patrick, Davis, Lehman, & Cooper, 2015)

There is a need to better understand the antecedent factors that lead to nonmedical opioid use by pregnant women in order to inform prevention, screening, and treatment efforts.(Krans & Patrick, 2016) While aggregate reports on substance use during pregnancy are available from national survey data,(SAMHSA, 2014) these reports describe broad trends. They do not identify groups at higher risk for prenatal substance use, nor do they specify individual characteristics that may predict nonmedical use of prescription opioids. Studies of hospital discharge data report trends in and correlates of maternal diagnosis of substance abuse (including opioid dependency) complicating childbirth,(Maeda, Bateman, Clancy, Creanga, & Leffert, 2014; Whiteman et al., 2014) but these studies only capture cases that were diagnosed and documented at the time of childbirth. They leave open the question about the scope of the problem of nonmedical opioid use prior to and during pregnancy. Women are highly motivated to care for their health during pregnancy, and they typically interact with clinicians on a regular basis, making this time period a unique window of opportunity for screening, diagnosis and treatment.

The effects of nonmedical opioid use on women and infants have a high potential for prevention and appropriate management.(ACOG Committee Opinion No. 524. 2012, SAMHSA 2008) New prescribing guidelines raise awareness about the risks associated with prescription opioid use during pregnancy, but offer few specific recommendations.(Dowell, Haegerich, & Chou 2016) For pregnant women with opioid dependency, comprehensive treatment, including medication-assisted therapy combined with adequate prenatal care, reduces the risk of obstetric complications and of NAS. (ACOG Committee Opinion No. 524. 2012, SAMHSA 2008) To develop strategies to prevent and appropriately treat nonmedical use of prescription opioids during pregnancy, there is a need for greater precision in knowledge about the correlates of nonmedical opioid use prior to and during pregnancy. There are currently no national studies that characterize pregnant women who report nonmedical use of prescription opioids, and this knowledge gap may constrain current policy efforts to address NAS and other effects of the opioid epidemic. The goal of this study was to use national survey data to describe characteristics of pregnant women who reported nonmedical opioid use in the prior year or over the past month.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data and study population

We analyzed data from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). The NSDUH provides population estimates of substance use and health-related behaviors in U.S. adolescents and adults using multistage area probability sampling. We pooled ten years of data (2005–2014) to create a sample of female respondents who reported being currently pregnant at the time of the survey. The sample included 8,721 (weighted N=23,855,041) non-institutionalized pregnant women, ages 12–44. Descriptive characteristics and model estimates were weighted to be nationally representative, accounting for the NSDUH sample design.

Variable measurement

The dependent variables were based on a pregnant respondent’s having reported using prescription opioids nonmedically or “for the feeling it caused.” Past year nonmedical opioid use occurred either “within the past 30 days” or “more than 30 days ago but within the past 12 months.” Past month use was coded among those with nonmedical opioid use only “within the past 30 days.” The NSDUH survey does not explicitly ask about the frequency or duration of substance use, nor does the survey ask if use was during pregnancy. We expect that most reports of past month nonmedical opioid use reflected use during pregnancy for many of those in the study population (who reported being currently pregnant at the time of the survey), as most pregnancies cannot be detected or confirmed before day 20 of the pregnancy.

An indicator for anxiety or depression was included if the respondent reported having either condition diagnosed in the past 12 months. We measured substance use, including alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana, in the past month and in the past year. Other relevant covariates included age (12–25, >=26), year (2005–2014), trimester of pregnancy, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Caucasian, African American, and Other, and Hispanic), health insurance (Private, Public – including Medicaid/CHIP/CHAMPUS, and None), marital status (married and unmarried), self-reported health status (excellent, very good, good, and fair or poor), and education (age 12–17 or less than high school, high school graduate, and some post-secondary or more,).

Analysis

We estimated the proportion of pregnant women reporting nonmedical opioid use during the past year or during the past month. We also described weighted demographic and clinical characteristics of the women in these groups and compared characteristics between those with nonmedical opioid use and those who do not report use, using Chi-square tests.

We constructed survey-weighted multivariable logistic regression models to examine the associations between patient characteristics and a) past year nonmedical opioid use and b) past month nonmedical opioid use. We modeled past year nonmedical use including the following independent variables: year (entered continuously as a restricted cubic spline with three knots), trimester, age, race, insurance, an indicator for anxiety/depression in the past year, separate indicators for past year use of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana, marital status, self-reported health status, and education. We then fit a model of past month nonmedical opioid use. Due to the limited frequency of events in the past month model (unweighted n=122; weighted n=217,106), we limited the number of covariates in multivariable models in order to avoid overfitting; covariates included: year (again using a restricted cubic spline with three knots), trimester, age, race, insurance, an indicator for anxiety/depression in the past year, and indicators for past 30 day use of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana.

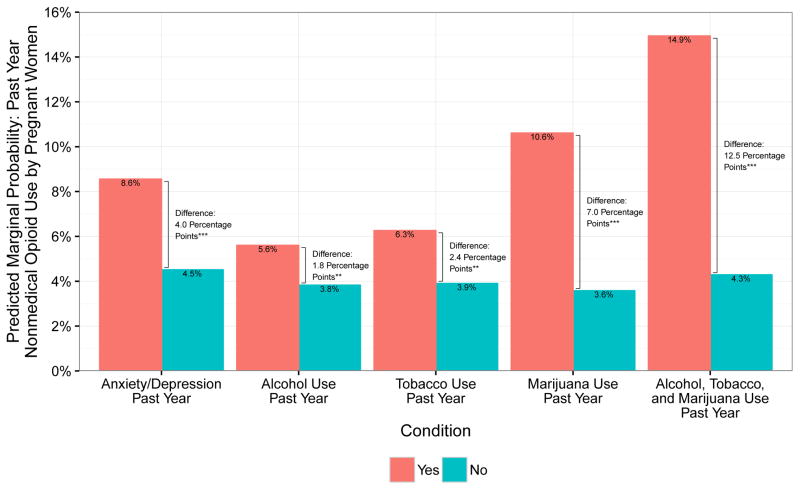

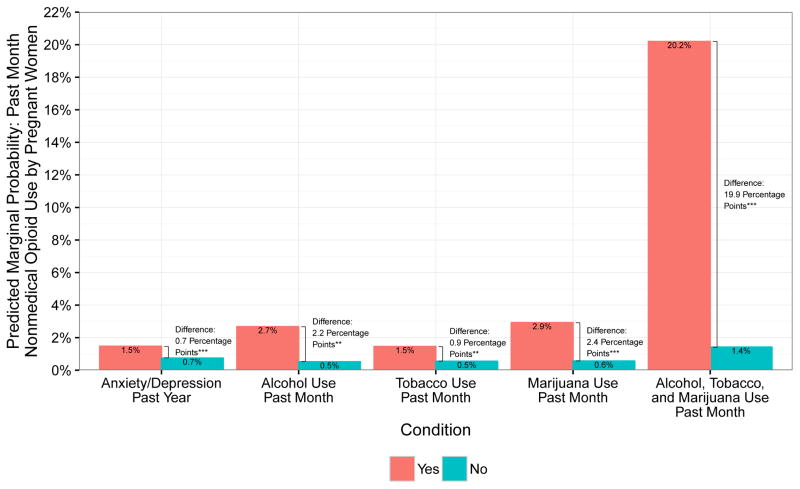

Predicted marginal probabilities of selected covariates based on model estimation are displayed in Figures 1 and 2. The bars in the figures indicate the probability of nonmedical opioid use for each level of, for example, past year alcohol use (yes and no) and setting all other covariate values to each individual’s own values. We then calculated the absolute difference in predicted marginal probabilities of nonmedical opioid use between alcohol users and nonusers and tested statistical significance of the difference. We also calculated predicted marginal probabilities for women with multiple risk factors, focusing on those who reported use of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana. This method puts into clinical perspective the absolute risk differences, based on key correlates of nonmedical opioid use in the past year or in the past month by pregnant women.

Figure 1.

Predicted marginal probabilities of past year nonmedical opioid use by pregnant women across multiple characteristics – anxiety or depression, alcohol use, tobacco use, marijuana use, and multiple substance use (alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana) in the past year. ***p<0.001 **p<0.01 *p<0.05

Figure 2.

Predicted marginal probabilities of past month nonmedical opioid use by pregnant women across multiple characteristics – anxiety or depression, alcohol use, tobacco use, marijuana use, and multiple substance use (alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana) in the past month. ***p<0.001 **p<0.01 *p<0.05

Analyses were conducted using R version 3.1.3, and two-sided P-values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Missing values accounted for <2% of our sample across all variables. This study was designated exempt from review by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Over 5% (5.1, 95% CI, 4.6–6.0) of pregnant women reported nonmedical use of prescription opioids over the past year; nearly 1% (0.9, 95% CI, 0.7–1.0) reported nonmedical opioid use during the past month (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Pregnant Women by Nonmedical Opioid Use in the Past Year and Past Month, 2005–2014

| Nonmedical Opioid Use, Past Year N=1,222,060 | No Nonmedical Opioid Use, Past Year N=22,632,981 | P-value | Nonmedical Opioid Use, Past Month N=217,106 | No Nonmedical Opioid Use, Past Month N=23,637,934 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.1% | 94.9% | 0.9% | 99.1% | |||

|

| ||||||

| Age, years | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| <=25 | 63.3% | 38.8% | 67.8% | 39.8% | ||

| >=26 | 36.7% | 61.2% | 32.2% | 60.2% | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.007 | 0.149 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Caucasian | 66.8% | 57.3% | 51.9% | 57.8% | ||

| Non-Hispanic African American | 14.0% | 14.5% | 24.6% | 14.4% | ||

| Non-Hispanic Other | 4.2% | 8.3% | 5.5% | 8.1% | ||

| Hispanic | 15.0% | 19.9% | 18.0% | 19.7% | ||

| Marital Status | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Married | 29.6% | 61.4% | 23.3% | 60.1% | ||

| Unmarried | 70.4% | 38.3% | 76.7% | 39.9% | ||

| Household Income | <0.001 | 0.004 | ||||

| <$20,000 | 35.6% | 23.2% | 44.3% | 23.7% | ||

| $20,000–$49,999 | 33.5% | 31.6% | 32.2% | 31.7% | ||

| $50,000–$74,999 | 13.8% | 17.2% | 10.1% | 17.1% | ||

| >=$75,000 | 17.1% | 28.0% | 13.4% | 27.6% | ||

| Education | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Age 12–17 or Less Than High School | 30.4% | 18.7% | 37.9% | 19.1% | ||

| High School Graduate | 32.7% | 25.6% | 27.9% | 25.9% | ||

| Some Post-secondary | 36.9% | 55.8% | 34.2% | 55.0% | ||

| Insurance | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Private | 31.8% | 54.2% | 25.2% | 53.3% | ||

| Medicaid/CHIP/CHAMPUS | 48.5% | 32.9% | 46.9% | 33.5% | ||

| None | 19.7% | 12.9% | 28.0% | 13.2% | ||

| Trimester | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| First | 45.2% | 30.7% | 49.1% | 31.3% | ||

| Second | 29.3% | 35.9% | 31.7% | 35.6% | ||

| Third | 25.5% | 33.4% | 19.2% | 33.1% | ||

| Self-reported Health Status | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Excellent | 19.5% | 35.3% | 15.1% | 34.7% | ||

| Very Good | 36.5% | 37.7% | 19.2% | 37.8% | ||

| Good | 30.4% | 22.0% | 43.5% | 22.2% | ||

| Fair or Poor | 13.6% | 5.0% | 22.2% | 5.3% | ||

| Anxiety or Depression | ||||||

| Past Year | 25.9% | 8.1% | <0.001 | 29.8% | 8.8% | <0.001 |

| Alcohol Use | ||||||

| Ever Used in Past Month | 23.9% | 8.1% | <0.001 | 49.2% | 8.6% | <0.001 |

| Ever Used in Past Year | 80.1% | 59.2% | <0.001 | 79.9% | 60.1% | 0.002 |

| Tobacco Use | ||||||

| Ever Used Tobacco in Past Month | 43.5% | 14.5% | <0.001 | 59.3% | 15.6% | <0.001 |

| Ever UsedTobacco in Past Year | 65.2% | 27.1% | <0.001 | 65.8% | 28.7% | <0.001 |

| Marijuana Use | ||||||

| Past Month | 22.9% | 2.6% | <0.001 | 41.6% | 3.3% | <0.001 |

| Past Year | 46.3% | 9.8% | <0.001 | 61.8% | 11.2% | <0.001 |

All descriptive characteristics incorporate NSDUH survey sampling design and weights, and Pearson Chi-square p-values are reported.

Compared to pregnant women who did not report past year nonmedical opioid use, those who did have opioid nonmedical use in the past year had a higher prevalence of anxiety or depression diagnoses (25.9% vs. 8.1%), and more frequently reported alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use in the past year (80.1% vs. 59.2%, 65.2% vs. 27.1% and 46.3% vs. 9.8%, respectively). Women reporting nonmedical opioid use over the past year also tended to be younger (63.3% age 12–25 vs. 38.8%), unmarried (70.4% vs. 38.3%), lower income (35.6% <$20,000 annual income vs. 23.2%), not completed high school (30.4% vs. 18.7%), have fair or poor health (13.6% vs. 5.0%), and to have government or no health insurance (68.2% vs. 45.8%), compared with nonusers (Table 1; p<0.05 for all comparisons shown). Characteristics of pregnant women reporting past month nonmedical use of prescription opioids revealed similar patterns, compared with nonusers. Pregnant women with nonmedical opioid use in the past 30 days reported comparatively higher rates of anxiety or depression and past year as well as higher rates of substance use in the past month, relative to those who did not report nonmedical opioid use in the past 30 days (Table 1).

In adjusted models, the following characteristics were associated with pregnant women’s reports of nonmedical opioid use within previous year: depression or anxiety diagnosis within the previous year (aOR=2.15, 95% CI 1.52–3.04), previous year use of alcohol (aOR=1.56, 95% CI 1.11–2.17), tobacco (aOR=1.72, 95% CI 1.17–2.53), and marijuana (aOR=3.44, 95% CI 2.47–4.81). Past year opioid nonmedical use was associated with younger age (12–25 vs. >35; aOR=3.37, 95% CI 1.20–9.46), being unmarried vs. married (aOR=1.38, 95% CI 1.00–1.90), and having Medicaid (aOR=1.40, 95% CI 1.02–1.94) or no health insurance (aOR=1.57, 95% CI 1.08–2.29), compared to private health insurance. Pregnant Caucasian women had higher odds of reporting past year nonmedical opioid use compared with African American women (aOR=1.61, 95%CI 1.09–2.36), and women reporting fair or poor health had more than twice the odds of past year nonmedical opioid use relative to those reporting excellent health (aOR 2.40, 95%CI 1.20–4.76; Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics Associated with Past Year Nonmedical Opioid Use among US Pregnant Women, 2005–2014

| Characteristic | aOR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| 12–25 | 1.38 (1.00, 1.90) | 0.05 |

| ≥26 | (reference) | |

| Trimester | ||

| First | 1.34 (0.93, 1.92) | 0.12 |

| Second | 0.92 (0.69, 1.24) | 0.60 |

| Third | (reference) | |

| Anxiety or Depression in Past Year | ||

| Yes | 2.15 (1.52, 3.04) | < 0.001 |

| No | (reference) | |

| Alcohol in Past Year | ||

| Yes | 1.56 (1.11, 2.17) | 0.01 |

| No | (reference) | |

| Tobacco in Past Year | ||

| Yes | 1.72 (1.17, 2.53) | 0.01 |

| No | (reference) | |

| Marijuana in Past Year | ||

| Yes | 3.44 (2.47, 4.81) | < 0.001 |

| No | (reference) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic Caucasian | 1.61 (1.09, 2.36) | 0.02 |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 0.96 (0.48, 1.90) | 0.90 |

| Hispanic | 1.16 (0.72, 1.87) | 0.56 |

| Non-Hispanic African American | (reference) | |

| Insurance | ||

| Medicaid/CHIP/CHAMPUS | 1.40 (1.02, 1.94) | 0.04 |

| None | 1.57 (1.08, 2.29) | 0.02 |

| Private | (reference) | |

| Marital Status | ||

| Unmarried | 1.60 (1.10, 2.32) | 0.02 |

| Married | (reference) | |

| Self-reported Health Status | ||

| Very Good | 1.28 (0.85, 1.92) | 0.25 |

| Good | 1.38 (0.89, 2.14) | 0.16 |

| Fair or Poor | 2.40 (1.20, 4.76) | 0.02 |

| Excellent | (reference) | |

| Education | ||

| 12–17 or Some High School | 1.18 (0.85, 1.65) | 0.32 |

| High School Graduate | 1.01 (0.69, 1.48) | 0.98 |

| Some Post-secondary or More | (reference) | |

All model estimates incorporate NSDUH survey sampling design and weights and include a linear spline with three knots to control for year.

Figure 1 displays predicted marginal probabilities of past year nonmedical opioid use among pregnant women by anxiety or depression, alcohol use, tobacco use, and marijuana use in the past year. Differences in predicted marginal probabilities were statistically significant for all characteristics evaluated. For a pregnant woman with a past-year diagnosis of anxiety or depression, the predicted probability of past year nonmedical opioid use was 8.6%, compared with 4.5% for a similar woman without anxiety or depression. Pregnant women who used alcohol, tobacco, or marijuana (vs. nonusers) also had higher predicted marginal probability of nonmedical opioid use in the past year (5.6% vs. 3.8%, 6.3% vs. 3.9%, and 10.6% vs. 3.6%, respectively). The predicted probability of past year nonmedical opioid use was markedly higher for a pregnant woman who reported using three substances (alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana) in the past year (14.9%) compared with a predicted probability of 4.3% for a similar woman who was a nonuser.

Shifting focus from the past year to the past month, Table 3 presents AORs of characteristics associated with pregnant women’s nonmedical opioid use within the previous 30 days, adjusted for covariates. Pregnant women with anxiety or depression in the past year had higher odds of past month nonmedical opioid use compared to women without these conditions (aOR 1.78, 95% CI 1.02–3.09). Those who reported using alcohol, tobacco, or marijuana in the past month had 2–5 times the odds of nonmedical opioid use during that same time period, compared with nonusers (aOR 5.00, 95% CI 2.66–9.40; aOR 2.86, 95% CI 1.49–5.51; aOR 4.71, 95% CI 2.42–9.16 respectively).

Table 3.

Characteristics Associated with Past Month Nonmedical Opioid Use among US Pregnant Women, 2005–2014

| Characteristic | AOR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| 12–25 | 2.13 (0.80, 5.65) | 0.13 |

| ≥26 | (reference) | |

| Trimester | ||

| First | 0.82 (0.36, 1.91) | 0.65 |

| Second | 1.25 (0.58, 2.73) | 0.57 |

| Third | (reference) | |

| Anxiety or Depression in Past Year | ||

| Yes | 1.90 (1.10, 3.30) | 0.02 |

| No | (reference) | |

| Alcohol in Past Month | ||

| Yes | 5.70 (3.11, 10.42) | < 0.001 |

| No | (reference) | |

| Tobacco in Past Month | ||

| Yes | 2.84 (1.55, 5.22) | 0.001 |

| No | (reference) | |

| Marijuana in Past Month | ||

| Yes | 5.74 (3.14, 10.47) | < 0.001 |

| No | (reference) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic Caucasian | 0.73 (0.29, 1.82) | 0.50 |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 0.74 (0.18, 2.94) | 0.67 |

| Hispanic | 1.15 (0.35, 3.73) | 0.82 |

| Non-Hispanic African American | (reference) | |

| Insurance | ||

| Medicaid/CHIP/CHAMPUS | 1.23 (0.46, 2.25) | 0.60 |

| None | 2.10 (0.79, 5.58) | 0.14 |

| Private | (reference) | |

All model estimates incorporate NSDUH survey sampling design and weights and include a linear spline with three knots to control for year.

Figure 2 displays predicted marginal probabilities of past month nonmedical opioid use among pregnant women by the same characteristics of interest – anxiety or depression in the past year, and alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use in the past month, as well as a measure for women who reported past-month use of multiple substances (alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana). Across all categories, the difference in predicted probability of past month nonmedical use of prescription opioids was significantly higher for a woman with a depression/anxiety diagnosis or who reported past month substance use. The most striking differences were predicted for a pregnant woman who reported past month use of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana, for whom the predicted probability of nonmedical opioid use was 20.2%, compared with 1.4% for a similar woman who was a nonuser.

DISCUSSION

Over 6 million US women become pregnant annually,(Curtin, Abma, Ventura, & Henshaw, 2013) and this analysis shows that approximately 300,000 pregnant women (5.1%) reported nonmedical use of prescription opioids during the prior year. More than 44,000 pregnant women (0.9%) reported nonmedical opioid use in the past month, where – for many - their use may coincide with and affect the pregnancy. Notably, pregnant women reporting use of multiple substances (alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana) have a substantially higher predicted probability of nonmedical opioid use.

Physiologic dependence on opioids at birth poses considerable health risks to infants, including the development of NAS.(Desai et al., 2015; Patrick et al., 2015) Pregnant women also suffer health, financial, and emotional decrements as a result of nonmedical use of prescription opioids,(McQueen, Murphy-Oikonen, & Desaulniers, 2015; Pan & Yi, 2013; Roberts & Pies, 2011) and treatment access for pregnant women is extraordinarily limited, especially for women who are low-income or living in rural areas.(De’Souza, 2015) Prevention and treatment strategies for nonmedical opioid use prior to and during pregnancy can effectively reduce perinatal risks,(ACOG Committee Opinion No. 524, 2012, SAMHSA, 2008) but this requires detection and access to appropriate services. In this study, the characteristics associated with nonmedical opioid use by pregnant women reveal populations in contact with the medical system, including women with depression/anxiety diagnoses and concurrent substance use. These populations may also have broader social needs related to their mental illness and substance use. Emerging clinical and policy efforts currently underway to address the opioid epidemic nationally may offer opportunities for targeted efforts to reach pregnant women at risk of nonmedical opioid use.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE AND POLICY

Clinical implications for detection and treatment of maternal opioid misuse

Screening for substance use is an integral part of preconception and maternity care.(ACOG Committee Opinion No. 524, 2012; AGOG Committee Opinion No. 473, 2011) Despite clear recommendations for routine screening for nonmedical opioid use (including opioid dependence), screening patterns are variable, and – where screening is reported – validated instruments are not consistently used, owing in part to limited options for referral and treatment access.(Miller, Lanham, Welsh, Ramanadhan, & Terplan, 2014; Oral & Strang, 2006) For women, early recognition of nonmedical opioid use (and detection and treatment of opioid dependence) may allow for tapering prior to planned pregnancies, and – when detected during pregnancy - appropriate treatment for opioid dependence can effectively reduce its pregnancy-related health risks.(AGOG Committee Opinion No. 473, 2011; SAMHSA, 2009) Additionally, while prescribing guidelines for opioid pain medications have received attention and updates in recent years, little specific attention is paid to reproductive-age women generally and to pregnant women specifically.(Dowell, Haegerich, & Chou 2016) Clinicians who care for women prior to and during pregnancy need clear, actionable guidance regarding appropriate pain management strategies that minimize the potential risks of opioid dependency.

Appropriate treatment for opioid dependence, a clinically-diagnosed condition that may be related to nonmedical opioid use, when detected during pregnancy, requires carefully-managed ongoing use of opioids through medication-assisted treatment.(SAMHSA, 2008) Abrupt discontinuation in an opioid-dependent pregnant woman can result in preterm labor, fetal distress, or fetal death.(Jones, O’Grady, Malfi, & Tuten, 2008) Patient needs are substantial, as is the level of effort and commitment required on the part of both the patient and the health care delivery system to effectively meet these needs. In reality, the ideal laid out in guidelines is rarely achieved owing to myriad barriers and challenges such as stigma, lack of resources, limited clinician capacity, and absence of qualified personnel (or great distance from qualified personnel).(Jackson & Shannon, 2012a, 2012b; Roberts & Pies, 2011; Rosenblatt, Andrilla, Catlin, & Larson, 2015; SAMHSA, 2009) Our analysis revealed that some of the nation’s most vulnerable pregnant women – those with mental illness and/or alcohol, tobacco, or marijuana use – are also most likely to report nonmedical opioid use, highlighting the potential maternal and neonatal clinical effects of under-detection and under-treatment. Some of the women with nonmedical opioid use that co-occurs with substance use or mental illness may also seek and receive treatment for their co-occurring conditions. For example, among the adults in our study sample, 25% of pregnant women with past month nonmedical opioid use and 38% of those with past year use also reported receiving mental health treatment in the past year, implying an important potential role for mental health care providers in screening for nonmedical opioid use.

Policy implications

In 2013, the Department of Health and Human Services estimated that the Affordable Care Act combined with the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act would result in an expansion of mental health and substance use disorder benefits and parity protections for 62 million Americans.(Beronio, Po, Skopec, & Glied, 2013) However, it is unclear whether these predictions have yet come to fruition, especially for pregnant women whose access to opioid-related and other substance use treatment may be hampered by costs, clinician supply shortages, and the choice of their state not to expand Medicaid.(Krans & Patrick, 2016)

Many low-income pregnant women are eligible for Medicaid coverage during pregnancy and for 60 days after childbirth. Nationally, Medicaid finances 48% of births;(Markus, Andres, West, Garro, & Pellegrini, 2014) but up to 25% of pregnant women are uninsured at some point in the year prior to pregnancy,(Kozhimannil, Abraham, & Virnig, 2012) and many lose eligibility for Medicaid coverage after 60 days, because income eligibility thresholds plummet from 250–300% of the Federal Poverty Level to 133% in most states.(Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010) There is wide variability across states in Medicaid coverage for methadone therapy and other treatments for opioid dependence.(Saloner, Stoller, & Barry, 2016) Even though the Affordable Care Act (ACA) provides for greater access to private health insurance coverage, the variability in mental health coverage in private markets mirrors those in Medicaid programs.(Garfield, Lave, & Donohue, 2010)

Also, workforce constraints severely limit the availability of clinicians who are qualified to treat nonmedical opioid use in pregnant women. Professional guidelines recommend co-management of opioid-dependent pregnant women by an obstetrician-gynecologist and an addiction medicine specialist,(ACOG Committee Opinion No. 524, 2012) but this specialized workforce supply is limited, especially in rural areas.(Kozhimannil et al., 2015; Rosenblatt et al., 2015) State and federal policy can influence clinician supply, as indicated by differential growth in physicians credentialed to provide opioid treatment based on state-level ACA implementation.(Knudsen, Lofwall, Havens, & Walsh, 2015)

Recently, the Government Accountability Office released a report highlighting the federal government’s approach to nonmedical opioid use in pregnancy and infants with NAS. The report discussed fragmentation in federal programs and concluded that federal efforts need more coordination and planning.(De’Souza, 2015) Since that time two notable pieces of legislation have been signed into law, aiming to improve access to treatment and outcomes for pregnant women with opioid dependence and infants with NAS – The Protecting Our Infants Act and the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act. Taken together these pieces of legislation aim to improve coordination federal efforts, improve access to treatment for pregnant and postpartum women and improve implementation of safe care plans for infants discharge home after substance exposure. Importantly, however, as this writing, the future of these pieces of legislation and the broader health-reforms on which they are premised is uncertain.

Limitations

There are several limitations of this analysis. First, repeat cross-sections of NSDUH data from 2005–2014 were pooled to increase the analytic sample size, but a longitudinal assessment was not possible. Also, geographic location variables were not added to NSDUH until 2007 and therefore were not included. Although self-report is considered a reliable measure for pregnancy status,(Overbeek et al., 2013) it is possible that respondents may have misreported or been unaware of their pregnancy status. Substance use may be under-reported among pregnant individuals, especially owing to social desirability bias.(Bessa et al., 2010; McQueen et al., 2015) Also, while we examined a number of important covariates, the NSDUH does not include important biological (e.g., gestational age) and contextual (e.g., prenatal care) factors that may inform prevention efforts, nor does it include information on duration or repetition of nonmedical opioid use over time. Finally, the reports by currently-pregnant survey respondents of past year and past month measures of nonmedical opioid use do not provide a precise categorization of use prior to and during pregnancy.

CONCLUSIONS

This analysis of a national sample of pregnant women revealed that depression or anxiety, alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use each independently predicted nonmedical opioid use in this population. Policy and prevention efforts to improve both screening and treatment could focus on the at-risk populations identified in this study.

Acknowledgments

Funding statement: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23DA038720 (S. Patrick). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Katy B. Kozhimannil is Associate Professor in the Division of Health Policy and Management at the University of Minnesota. She conducts research to inform the development, implementation, and evaluation of health policy that impacts health care delivery, quality, and outcomes during critical times in the lifecourse, including pregnancy and childbirth.

Amy J. Graves is Statistician in the Division of Health Policy and Management at the University of Minnesota. She conducts data analyses to inform policy making and clinical care for women, children, and beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid programs.

Bob Levy is Assistant Professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health at the University of Minnesota Medical School. He is a family physician and addiction medicine specialist who treats pregnant women for substance use disorders.

Stephen W. Patrick is Assistant Professor of Pediatrics and Health Policy at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. He is a practicing neonatologist, health services researcher and national expert on neonatal abstinence syndrome and the opioid epidemic.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 524: Opioid abuse, dependence, and addiction in pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012;119(5):1070–6. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318256496e. http://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e318256496e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AGOG Committee Opinion No. 473: substance abuse reporting and pregnancy: the role of the obstetrician-gynecologist. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011;117(1):200–1. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820a6216. http://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820a6216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beronio K, Po R, Skopec L, Glied S. Affordable Care Act Will Expand Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Benefits and Parity Protections for 62 Million Americans. ASPE Research Brief. 2013 Retrieved from http://aspe.hhs.gov/report/affordable-care-act-expands-mental-health-and-substance-use-disorder-benefits-and-federal-parity-protections-62-million-americans.

- Bessa MA, Mitsuhiro SS, Chalem E, Barros MM, Guinsburg R, Laranjeira R. Underreporting of use of cocaine and marijuana during the third trimester of gestation among pregnant adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(3):266–9. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.007. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creanga Aa, Sabel JC, Ko JY, Wasserman CR, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Taylor P, … Paulozzi LJ. Maternal Drug Use and Its Effect on Neonates. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2012;119(5):924–933. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824ea276. http://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824ea276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin SC, Abma JC, Ventura SJ, Henshaw SK. Pregnancy rates for U.S. women continue to drop. NCHS Data Brief. 2013;(136):1–8. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24314113. [PubMed]

- De’Souza V. Prenatal Drug Use and Newborn Health: Federal Efforts Need Better Planning and Coordination. GAO-15-203. Washington, D.C: 2015. Retreived from http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-15-203. [Google Scholar]

- Desai RJ, Hernandez-Diaz S, Bateman BT, Huybrechts KF. Increase in prescription opioid use during pregnancy among Medicaid-enrolled women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2014;123(5):997–1002. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000208. http://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai RJ, Huybrechts KF, Hernandez-Diaz S, Mogun H, Patorno E, Kaltenbach K, … Bateman BT. Exposure to prescription opioid analgesics in utero and risk of neonatal abstinence syndrome: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h2102. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2102. http://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain--United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624–1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield RL, Lave JR, Donohue JM. Health reform and the scope of benefits for mental health and substance use disorder services. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61(11):1081–6. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.11.1081. http://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2010.61.11.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudak ML, Tan RC. Neonatal Drug Withdrawal. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):e540–e560. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3212. http://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A, Shannon L. Barriers to receiving substance abuse treatment among rural pregnant women in Kentucky. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2012a;16:1762–1770. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0923-5. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-011-0923-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A, Shannon L. Examining barriers to and motivations for substance abuse treatment among pregnant women: does urban-rural residence matter? Women & Health. 2012b;52(6):570–86. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2012.699508. http://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2012.699508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HE, O’Grady KE, Malfi D, Tuten M. Methadone maintenance vs. methadone taper during pregnancy: maternal and neonatal outcomes. The American Journal on Addictions. 2008;17(5):372–86. doi: 10.1080/10550490802266276. http://doi.org/10.1080/10550490802266276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid/SCHIP Income Eligibility for Pregnant Women, by State, 2008. 2010 Retreived from statehealthfacts.org.

- Knudsen HK, Lofwall MR, Havens JR, Walsh SL. States’ implementation of the Affordable Care Act and the supply of physicians waivered to prescribe buprenorphine for opioid dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;157:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.09.032. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozhimannil KB, Abraham JM, Virnig B. National trends in health insurance coverage of pregnant and reproductive-age women, 2000 to 2009. Women’s Health Issues. 2012;22(2):e135–41. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.12.002. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozhimannil KB, Casey MM, Hung P, Han X, Prasad S, Moscovice IS. The Rural Obstetric Workforce in US Hospitals: Challenges and Opportunities. The Journal of Rural Health. 2015;v doi: 10.1111/jrh.12112. n/a–n/a. http://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MS, Demissie K, Yang H, Platt RW, Sauvé R, Liston R. The contribution of mild and moderate preterm birth to infant mortality. JAMA. 2000;284(7):843–849. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.7.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krans EE, Patrick SW. Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy: Health Policy and Practice in the Midst of an Epidemic. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016;128(1):4–10. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001446. http://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda A, Bateman BT, Clancy CR, Creanga AA, Leffert LR. Opioid abuse and dependence during pregnancy: temporal trends and obstetrical outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2014;121(6):1158–65. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000472. http://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000000472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus AR, Andres E, West KD, Garro N, Pellegrini C. Medicaid covered births, 2008 through 2010, in the context of the implementation of health reform. Women’s Health Issues. 2014;23(5):e273–80. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.06.006. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen KA, Murphy-Oikonen J, Desaulniers L. Maternal Substance Use and Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome: A Descriptive Study. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2015;19(8):1756–65. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1689-y. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-015-1689-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction during pregnancy. SAHMSA/CSAT Treatment Improvement Protocols. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA); 2008. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C, Lanham A, Welsh C, Ramanadhan S, Terplan M. Screening, testing, and reporting for drug and alcohol use on labor and delivery: a survey of Maryland birthing hospitals. Social Work in Health Care. 2014;53(7):659–69. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2014.916375. http://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2014.916375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral R, Strang T. Neonatal illicit drug screening practices in Iowa: the impact of utilization of a structured screening protocol. Journal of Perinatolog. 2006;26(11):660–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211601. http://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek A, van den Berg MH, Hukkelhoven CWPM, Kremer LC, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Tissing WJE, van Dulmen-den Broeder E. Validity of self-reported data on pregnancies for childhood cancer survivors: a comparison with data from a nationwide population-based registry. Human Reproduction. 2013;28(3):819–27. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des405. http://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/des405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan IJ, Yi HY. Prevalence of hospitalized live births affected by alcohol and drugs and parturient women diagnosed with substance abuse at liveborn delivery: United States, 1999–2008. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2013;17:667–676. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1046-3. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-012-1046-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick SW, Davis MM, Lehman CU, Cooper WO. Increasing incidence and geographic distribution of neonatal abstinence syndrome: United States 2009 to 2012. Journal of Perinatology. 2015;35(8):667. doi: 10.1038/jp.2015.63. http://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2015.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick SW, Dudley J, Martin PR, Harrell FE, Warren MD, Hartmann KE, … Cooper WO. Prescription Opioid Epidemic and Infant Outcomes. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):842–850. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3299. http://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-3299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick SW, Kaplan HC, Passarella M, Davis MM, Lorch Sa. Variation in treatment of neonatal abstinence syndrome in US Children’s Hospitals, 2004–2011. Journal of Perinatology. 2014 Jan;:1–6. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.114. http://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2014.114. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Patrick SW, Schumacher RE, Benneyworth BD, Krans EE, McAllister JM, Davis MM. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome and Associated Health Care Expenditures, United States, 2000–2009. JAMA. 2012;307(18):1934–1940. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3951. http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.3951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA); 2014. NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4863. Retrieved from http://oas.samhsa.gov/NSDUH/2k10NSDUH/2k10Results.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SCM, Pies C. Complex calculations: how drug use during pregnancy becomes a barrier to prenatal care. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2011;15(3):333–41. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0594-7. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-010-0594-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CHA, Catlin M, Larson EH. Geographic and specialty distribution of US physicians trained to treat opioid use disorder. Annals of Family Medicine. 2015;13(1):23–6. doi: 10.1370/afm.1735. http://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha TD, Kerridge BT, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Zhang H, Jung J, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Huang B, Hasin DS, Grant BF. Nonmedical Prescription Opioid Use and DSM-5 Nonmedical Prescription Opioid Use Disorder in the United States. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2016;77(6):772–80. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m10386.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saloner B, Stoller KB, Barry CL. Medicaid Coverage for Methadone Maintenance and Use of Opioid Agonist Therapy in Specialty Addiction Treatment. Psychiatric Services. 2016;1(67):6, 676–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Substance Abuse Treatment: Addressing the Specific Needs of Women. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 51 HHS Publication No. (SMA) 09–4426. Rockville, MD: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolia VN, Patrick SW, Bennett MM, Murthy K, Sousa J, Smith PB, Spitzer AR. Increasing Incidence of the Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome in U.S. Neonatal ICUs. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(22):2118–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1500439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman VE, Salemi JL, Mogos MF, Cain MA, Aliyu MH, Salihu HM. Maternal opioid drug use during pregnancy and its impact on perinatal morbidity, mortality, and the costs of medical care in the United States. Journal of Pregnancy. 2014;2014:906723. doi: 10.1155/2014/906723. http://doi.org/10.1155/2014/906723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]