Summary

Sleep difficulties are emerging as a risk factor for dementia. This study examined the effect of sleep and amyloid deposition on cognitive performance in cognitively normal adults. Sleep efficiency was determined by actigraphy. Cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 levels<500pg/mL, indicating amyloid deposition, was present in 23 participants. Psychometric tests included the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, Trail Making Test A and B, Animal Fluency, Letter Number Sequencing, and the Mini Mental State Examination. The interaction term of sleep efficiency and amyloid deposition status was a significant predictor of memory performance as measured by total Selective Reminding Test scores. While Trail Making Test B performance was worse in those with amyloid deposition, sleep measures did not have an additive effect. In this study, amyloid deposition was associated with worse cognitive performance, and poor sleep efficiency specifically modified the effect of amyloid deposition on memory performance.

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, sleep disturbance, memory, Alzheimer's disease

Introduction

Optimal cognitive performance requires sleep. In cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses, decreased sleep efficiency or poor sleep quality is associated with worse psychometric performance in cognitively normal older adults, especially in memory and executive functioning (Blackwell et al.,2006; Blackwell et al., 2011; Potvin et al, 2012). Experimental models show that the sleep-wake cycle may regulate amyloid-beta levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (Kang et al. 2009; Xie et al., 2013), suggesting poor sleep quality may affect the pathophysiological mechanisms of amyloid-beta deposition, an important step of Alzheimer's Disease (AD)pathogenesis(Ju et al., 2014). Subjective longer sleep latency and poor sleep quality have been associated with increased amyloid burden onpositron emission tomography (Spira et al., 2013; Sprecher et al., 2015; Brown et al., 2016; Branger et al., 2016). Decreased CSF amyloid-beta-42 (Aβ42) levels, an early biomarker of amyloid plaque deposition, have been associated with decreased sleep quality based on objective measures in cognitively normal middle-aged adults (Ju et al., 2013). Additionally, the amyloid burden in the medial prefrontal cortex has been associated with impairment in non-REM slow wave activity, mediating impairment in memory consolidation (Mander et al., 2015). No studies have examined the interaction between amyloid deposition and sleep on psychometric performance in cognitively normal adults. This study assessed the effect of sleep on cognitive performance, accounting for the presence of amyloid deposition based on CSF Aβ42 levels.

Methods

Participants aged ≥45 years were drawn from longitudinal IRB-approved studies at the Washington University Knight Alzheimer's Disease Research Center as previously described (Ju et al., 2013). The Washington University Human Research Protection Office approved all procedures, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants with psychometric testing within one year of CSF donation and within three years of actigraphy recording were included. All had normal cognition based on a Clinical Dementia Rating score of 0 (Morris, 1993).

Trained psychometricians administered the psychometric tests. Free and total scores from the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (SRT) assessed memory, and scores from Trail Making Test A (TMA) and B (TMB), Animal Fluency, and Letter Number Sequencing assessed executive function (Pizzie et al., 2014). The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) assessed general cognitive status (Folstein et al., 1995). All psychometric test scores were analyzed as continuous variables. Higher scores on all tests, except TMA and TMB, indicated better performance.

CSF Aβ42 levels, measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (INNOTEST; Immogenetics, Ghent, Belgium) as previously described, were analyzed as a categorical variable (Ju et al., 2013). A cutoff value of <500 pg/mL was used to indicate amyloid plaque deposition, based on prior studies correlating with cortical amyloid deposition on Pittsburgh Compound B imaging (Fagan et al., 2006; Fagan et al., 2009). A fasting CSF was collected at the same time (7-8am) by lumbar puncture for all participants.

Sleep was objectively measured using wrist actigraphy (Actiwatch2®, Philips Respironics) recording for 7-14 days (mean 13.6 ±1.1 days). Participants pressed a button on the actigraphs to indicate bedtime and wake time, and also kept concurrent sleep diaries. Scoring of actigraphy was performed manually through Actiware (Philips Respironics) using a standardized protocol to reconcile actigraphic and sleep diary data, as previously described (Ju et al., 2013), using wake threshold at the most sensitive “low” setting of 20. Our primary sleep measure was sleep efficiency as a measure of sleep quality, since this measure was associated with amyloid deposition in a prior study (Ju et al., 2013). Sleep efficiency was defined as total sleep time divided by the time in bed. A secondary analysis with total sleep time as a measure of sleep quantity was also performed.

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics 24 (IBM, New York). Student's T-tests were used for continuous variables, and the Chi-squared test for categorical variables. Multivariate linear regressions were performed with cognitive tests as the dependent variables. Separate analyses were initially performed with sleep efficiency or Aβ42 status as predictor variables, with age, sex, race, education, body mass index, and apolipoproteinE-ε4 allele as covariates. To assess the interaction of sleep and Aβ42 status, multivariate linear regression was performed with sleep efficiency or total sleep time (as continuous variables), Aβ42 status, and their interaction term as covariates, also adjusting for the covariates used in the previous models. Since this analysis was an exploratory post-hoc study, we did not correct for multiple comparisons. Race was included as a covariate due to prior literature showing worse sleep efficiency in blacks (Mezick et al., 2008).

Results

Ninety-eight participants met inclusion criteria, of whom 23 had Aβ42< 500 pg/mL, indicating amyloid plaque deposition. Except for age, demographic characteristics and cognitive scores were similar between the Aβ42 groups (Table 1). The absolute duration between actigraphy recording and lumbar puncture, between actigraphy recording and psychometric testing, and between lumbar puncture and psychometric testing were all less than one year on average (Table 1). The order of the three procedures occurred in all six possible combinations, with 59% having lumbar puncture prior to actigraphy, 53% having psychometric testing prior to actigraphy, and 46% having psychometric testing prior to lumbar puncture.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics and Cognitive Test Scores by Aβ42 Status.

| Overall Cohort | Aβ42 <500 pg/mL N = 23 | Aβ42 >500 pg/mL N = 75 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | |||||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 69.0 (7.1) | 72.0 (6.2) | 68.0 (7.0) | 0.016 | |

| Male | 41.8% | 43.5 | 41.3% | 0.855 | |

| White | 95.9% | 95.7% | 96.0% | 0.941 | |

| BMI | 27.7 (5.0) | 27.0 (4.4) | 28.0 (5.2) | 0.447 | |

| Education, years, mean (SD) | 16.0 (2.3) | 15.7 (2.4) | 16.0 (2.3) | 0.474 | |

| Time from actigraphy to LP, d, mean (SD) | 355 (238) | 351 (201) | 356 (250) | 0.918 | |

| Time from LP to CA, d, mean (SD) | 167 (152) | 161 (142) | 169 (156) | 0.817 | |

| Time from CA to actigraphy, d, mean (SD) | 216 (181) | 200 (163) | 220 (187) | 0.645 | |

| Number of actigraphy days | 13.6 (1.1) | 13.8 (0.4) | 13.5 (1.3) | 0.304 | |

| Mean sleep efficiency, % | 82.9 (7.7) | 81.4 (6.8) | 83.4 (7.9) | 0.282 | |

| Total sleep time, minutes | 404 (52) | 402 (38) | 405 (55) | 0.802 | |

| ApoEε4 allele | 39.8% | 47.8% | 37.3% | 0.368 | |

| CSF Aβ42 levels | 705.3 (237.8) | 391.0 (61.5) | 801.6 (181.3) | <0.001 | |

| Cognitive Test Scores | |||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||

| Free SRT, mean (SD) | 34.0 (4.5) | 32.8 (4.3) | 34.4 (4.5) | 0.148 | 0.263 |

| Total SRT, mean (SD) | 47.9 (0.3) | 47.8 (0.5) | 48.0 (0.2) | 0.049 | 0.104 |

| Animal Fluency, mean (SD) | 22.6 (5.4) | 21.6 (5.5) | 22.9 (5.4) | 0.319 | 0.825 |

| TMA, seconds, mean (SD) | 29.9 (8.0) | 30.3 (6.5) | 29.8 (8.5) | 0.822 | 0.462 |

| TMB, seconds, mean (SD) | 71.9 (25.4) | 86.2 (33.4) | 67.6 (21.0) | 0.020 | 0.008 |

| Letter Number, mean (SD) | 9.9 (2.3) | 9.6 (2.1) | 10.0 (2.4) | 0.488 | 0.965 |

| MMSE, mean (SD) | 29.3 (1.0) | 29.0 (1.2) | 29.4 (1.0) | 0.201 | 0.283 |

Abbreviations: Aβ42, β-amyloid 42; BMI, body mass index; CA, cognitive assessment; LP, lumbar puncture; SRT, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test; TMA, Trail Making Test A; TMB, Trail Making Test B; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination.

The presence of amyloid deposition (Aβ42 < 500 pg/mL) worsened total SRT scores by -0.14 points in the unadjusted model, but this effect was not significant after adjustment. Amyloid deposition worsened TMB performance by 18.6 seconds (95 CI 6.89 to 30.29), and this difference remained significant after adjustment for covariates (Table 1).

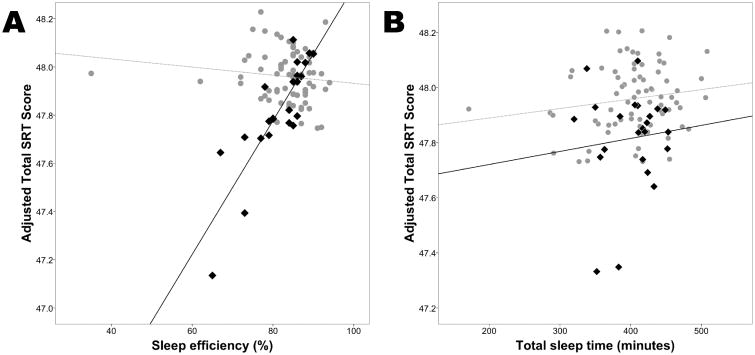

Sleep efficiency alone had no significant effect on any cognitive test, before or after adjustment for covariates. However, the interaction term of sleep efficiency and Aβ42 status had a significant effect on total SRT scores, before (β=0.030, 95 CI 0.010 to 0.049, p=0.003) and after (β=0.026, 95 CI 0.006 to 0.046, p=0.011) adjustment. The interaction term did not have a significant effect on any of the other psychometric test scores. This finding indicates that worse sleep efficiency in the presence of amyloid deposition has negative effects specifically on memory performance (Figure 1A). In a secondary analysis, total sleep time alone had no significant effect on any cognitive test, before or after adjustment for covariates. The interaction term of total sleep time and Aβ42 status had a weak effect on total SRT scores after adjustment for covariates (β=-0.001, 95 CI -0.001 to 0.000, p=0.010) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Interaction of sleep measurements and amyloid deposition on memory performance.

A. In a cognitively normal cohort, sleep efficiency (total sleep time divided by time in bed) was positively correlated with memory performance as measured by the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (SRT) total score, only in those with amyloid deposition as determined by CSF Aβ42levels < 500 pg/mL (black diamonds, black solid line). There was no relationship between sleep efficiency and memory performance in those without amyloid deposition (gray circles, gray dotted line). B. The interaction term of total sleep time and Ab42 status had a weak effect on memory performance. Memory scores were adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, education, and presence of the apolipoproteinE-ε4 allele.

Discussion

We assessed the interaction of sleep and amyloid deposition on psychometric performance. We found that amyloid deposition, as assessed by CSF Aβ42 levels, and sleep efficiency interact in their effects on memory performance as measured by total SRT scores, even though amyloid deposition and sleep measures did not have individual effects on memory performance. Amyloid deposition was associated with worse performance on TMB, a test of executive function, but not after adjustment for age and other covariates. There was no significant independent effect of sleep efficiency or total sleep time on the other psychometric tests assessed in this cognitively normal population.

While worse sleep quality has been associated with worse psychometric performance in older adults (Yaffe, et al., 2015), no studies have examined the possible interaction of amyloid deposition and sleep quality on psychometric performance. This study is the first to report an interaction between CSF AD biomarkers and sleep efficiency on psychometric performance in cognitively normal adults, even after adjustment for covariates, including age and apolipoproteinE-ε4 status.

The relationship between sleep, cognition, and AD pathology is complex. Our results suggest that worse sleep is associated with worse memory function only when amyloid deposition is present. Alternatively, the amyloid deposition may alter or magnify the effects of sleep disturbance on memory performance. Cortical amyloid deposition has been associated with memory consolidation impairment not directly, but through impairment in non-REM slow wave activity (Mander et., 2015). A possible mechanism underlying our results may be that decreased sleep efficiency may be associated with decreased non-REM slow wave activity, leading to worse memory performance in those with amyloid deposition. Improving sleep efficiency and consolidation may lead to increased non-REM slow wave activity, which, in turn, may improve memory performance. Additionally, improved sleep efficiency may mitigate the development of tau-related neurofibrillary tangle pathology in those positive for the apolipoproteinE-ε4 allele (Lim et al., 2013).

Strengths of our study include objective sleep measures, extensive psychometric testing, and known CSF AD biomarkers in a well-defined cohort. The average time between all measurements was less than one year. In a cognitively normal population with cognitive status determined not by psychometric testing but by Clinical Dementia Rating scale, it is unlikely that significant deficits in psychometric testing would develop during this short period. Limitations of this study include the small sample size. There were also no polysomnographic data to determine whether obstructive sleep apnea or other primary sleep disorders caused poor sleep efficiency or reduced total sleep time. However, body mass index, which is correlated with obstructive sleep apnea, was included as a covariate in analysis. Due to the small sample size, mood and anxiety disorders were also not assessed. Additionally, the overall good performance on psychometric tests from this well-educated, cognitively normal group may have contributed to higher scores and therefore reduced effect sizes.

Despite these limitations, we did identify effects of sleep on psychometric performance, when taking amyloid deposition status into account. Longitudinal follow-up will be needed to determine whether these effects become more pronounced overtime. Previous epidemiological studies have shown that poor sleep may contribute to worse cognitive performance, but these studies did not include data on amyloid deposition and may have included those with mild cognitive impairment (Scullin and Bliwise, 2015). Our results suggest that the effect of early AD pathology on cognitive performance may vary as a function of sleep. Future studies that assess more detailed sleep parameters, AD biomarkers, and longitudinal cognitive trajectories will be necessary to determine the contribution of sleep to the progression from preclinical to clinical AD.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Collection and management of research in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging [P50AG005681, P01AG003991, and P01AG026276]; Fred Simmons and Olga Mohan, and the Charles F. and Joanne Knight Alzheimer's Research Initiative of the Washington University Knight Alzheimer's Disease Research Center.

Collection, management, and analysis of data for research in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke [K23NS089922] and the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR000448, sub-award KL2TR000450, from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH.

No funder or sponsor had a role in design and conduct of the study, interpretation of the data, or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. There were no off-label or investigational use materials in this study.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Molano, Ju, Roe

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Molano, Ju, Roe

Drafting of the manuscript: Molano, Ju, Roe

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Molano, Ju, Roe

Statistical analysis: Ju

Data Access, Responsibility, and Analysis: Yo-El Ju had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest associated with this work, including relevant financial interests, activities, relationships, and affiliations.

References

- Blackwell T, Yaffe K, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Poor sleep is associated with impaired cognitive function in older women: The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:405–410. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell T, Yaffe K, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Association of sleep characteristics and cognition in older community-dwelling men: The MrOS sleep study. Sleep. 2011;34:1347–1356. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potvin O, Lorrain D, Forget H, et al. Sleep quality and 1-year incident cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults. Sleep. 2012;35:491–499. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JE, Lim MM, Bateman RJ, et al. Amyloid-beta dynamics are regulated by orex in and the sleep-wake cycle. Science. 2009;326:1005–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1180962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, et al. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science. 2013;342:373–377. doi: 10.1126/science.1241224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju YS, Lucey BP, Holtzman DM. Sleep and Alzheimer disease pathology – a bidirectional relationship. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:115–119. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spira A, Gamaldo AA, An Y, et al. Self-reported sleep and β-amyloid deposition in community-dwelling older adults. 2013;70:1537–1543. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.4258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher KE, Bendlin BB, Racine AM, et al. Amyloid burden is associated with self-reported sleep in nondemented late middle-aged adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:2568–2576. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BM, Rainey-Smith SR, Villemagne VL, et al. The relationship between sleep quality and brain amyloid burden. Sleep. 2016;39:1063–1068. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branger P, Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Tomadesso C, et al. Relationships between sleep quality and brain volume, metabolism, and amyloid deposition in late adulthood. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;41:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju YS, McLeland JS, Toedebusch CD, et al. Sleep quality and preclinical Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:587–593. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mander BA, Marks SM, Vogel JW, et al. β-amyloid disrupts human NREM slow waves and related hippocampus-dependent memory consolidation. Nat Neuroscience. 2015;18:1051–1057. doi: 10.1038/nn.4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzie R, Hindman H, Roe CM, et al. Physical activity and cognitive trajectories in cognitively normal adults. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014;28:50–57. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31829628d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psych Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, et al. Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Abeta42 in humans. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:512–519. doi: 10.1002/ana.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Shah AR, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid tau and ptau(181) increase with cortical amyloid deposition in cognitively normal individuals: implications for future clinical trials of Alzheimer's disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1:371–380. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezick EJ, Matthews KA, Hall M, et al. Influence of race and socioeconomic status on sleep: Pittsburgh SleepSCORE project. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:410–416. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816fdf21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe K, Falvey CM, Hoang T. Connections between sleep and cognition in older adults. Lancet Neurol. 2015;13:1017–1028. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70172-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim AS, Yu L, Kowgier M, et al. Modification of the relationship of the apolipoprotein E ε4 allele to the risk of Alzheimer disease and neurofibrillary tangle density by sleep. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:1544–1551. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.4215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scullin MK, Bliwise DL. Sleep, Cognition, and Normal Aging: Integrating a half-centure of multidisciplinary research. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:97–137. doi: 10.1177/1745691614556680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]