Abstract

The use of standard molecular dynamics simulation methods to predict the interactions of a protein with a material surface have the inherent limitations of lacking the ability to determine the most likely conformations and orientations of the adsorbed protein on the surface and to determine the level of convergence attained by the simulation. In addition, standard mixing rules are typically applied to combine the nonbonded force field parameters of the solution and solid phases the system to represent interfacial behavior without validation. As a means to circumvent these problems, the authors demonstrate the application of an efficient advanced sampling method (TIGER2A) for the simulation of the adsorption of hen egg-white lysozyme on a crystalline (110) high-density polyethylene surface plane. Simulations are conducted to generate a Boltzmann-weighted ensemble of sampled states using force field parameters that were validated to represent interfacial behavior for this system. The resulting ensembles of sampled states were then analyzed using an in-house-developed cluster analysis method to predict the most probable orientations and conformations of the protein on the surface based on the amount of sampling performed, from which free energy differences between the adsorbed states were able to be calculated. In addition, by conducting two independent sets of TIGER2A simulations combined with cluster analyses, the authors demonstrate a method to estimate the degree of convergence achieved for a given amount of sampling. The results from these simulations demonstrate that these methods enable the most probable orientations and conformations of an adsorbed protein to be predicted and that the use of our validated interfacial force field parameter set provides closer agreement to available experimental results compared to using standard CHARMM force field parameterization to represent molecular behavior at the interface.

I. INTRODUCTION

Protein–surface interactions are fundamental in numerous applications in bioengineering and biotechnology, such as biocompatibility of implant biomaterials,1–5 tissue engineering,6–8 drug delivery,9–11 bioseparation surfaces,12–14 biosensors,15–17 and technology for biodefense.18–24 To predict and control the interactions between proteins and material surfaces, it is important to have a basic understanding of the molecular-level details of protein adsorption at the solution–solid material interface.25

Over the past several decades, protein adsorption has been widely studied using an array of experimental techniques such as circular dichroism (CD),26–31 surface plasmon resonance (SPR) spectroscopy,32–35 amino acid labeling/mass spectrometry (AAL/MS),36–38 atomic force microscopy (AFM),39–42 Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy,2,43–45 fluorescence spectra,46–48 and ellipsometry.49–52 However, these experimental techniques alone are not capable of providing complete molecular-level information on the structure of the adsorbed protein on the surface.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations employing all-atom empirical force fields (FFs), on the other hand, are intrinsically capable of capturing the complete picture of the atomistic-level events of molecular interactions. However, MD methods need to be first tuned and validated before they can be confidently applied in the simulation of a particular molecular system. In this context, we address two main limitations of the application of the standard MD methods in the simulation of protein–surface interactions: (1) the FF parameters that govern the molecular interactions between the amino-acid residues of the protein and the material surface, and (2) the ability of MD simulations to effectively provide sufficient sampling of such a large molecular system to capture such events as the conformational shift of the protein upon its interactions with the surface and its orientation with respect to the surface.5,53

The first limitation of the application of the standard MD methods in protein adsorption simulations is that the FF parameters that are used have typically been empirically developed and optimized over a few decades for the simulation of proteins in solution, but not for the simulation of their behavior at a liquid–solid interface. Because of the influence of the material surface on the protein, there can be considerable variation in the conformational behavior of the protein adsorbing on a material surface in comparison to the conformational behavior of the protein simply in aqueous solution. Hence, when the default parameters from a regular MD FF are utilized in the simulation of protein adsorption behavior, the simulation will still run successfully; however, it may produce very unrealistic results. In order to achieve accurate MD simulations of protein–surface interactions, the FF parameters that represent intraphase interactions (i.e., the protein in solution and the solid material surface) may need to be supplemented with a separate third set of tuned and validated nonbonded FF parameters to independently represent the interphase interactions (i.e., interactions between the amino-acid residues of the protein, the aqueous solution, and the solid material surface).54,55

Our previously developed dual-force-field CHARMM program (Dual-FF CHARMM),55 which is an adaptation of the CHARMM molecular simulation program,56 enables the user to control the interphase interactions using this separate set of nonbonded FF parameters, which we call the interfacial FF (IFF), to represent interphase behavior in protein adsorption simulations. We have also incorporated a similar capability in the LAMMPS simulation program.57 Dual-FF CHARMM is a significant development for protein adsorption studies as it allows the IFF to be individually parameterized using experimental data to more accurately represent amino acid–surface interactions whereas the conformational behavior of the protein in solution is separately represented by its own validated protein FF. We hypothesize that using environment-dependent FF parameters of this type will enable MD simulation of protein adsorption behavior to produce realistic results.5

In our previous work using the Dual-FF CHARMM method, we parameterized the IFF for the interactions of amino-acid residues with a (110) surface plane of high-density polyethylene (HDPE),58 silica glass,59 and poly(methyl methacrylate) surfaces, and achieved good correlations with our experimental results. In those studies, adsorption free energies, ΔAoads, of ten small host–guest peptides on each type of surface were calculated using umbrella sampling simulations (with the default CHARMM FF parameters) and compared with the experimental values determined by SPR/AFM experimental methods.35,60 These comparisons showed substantial differences between simulation and experimental adsorption free energy values. Subsequently, IFF parameters were adjusted to decrease these differences, which brought ΔAoads values in agreement with their respective experimental data (e.g., in the peptide−HDPE adsorption study, the R correlation coefficient increased from 0.00 when the default CHARMM parameters were used for the IFF to 0.88 when tuned-IFF parameters were used). Based on the corresponding atom types, we then used the tuned parameters of these ten guest amino acids to similarly adjust the IFF parameters of the remaining ten amino acids.58,59

In addition to the FF requirements, the second limitation of the application of the standard MD methods in protein adsorption simulation is the question of their efficiency to capture the entire adsorption behavior of the protein, including the change in its conformation and orientation on a material surface during adsorption. Experimental measurements of protein adsorption behavior typically provide averaged properties of billions of adsorbed proteins over timeframes of seconds and longer. If simulation results are to be compared to such experimental values, the simulation must also provide such averaged values as well. These values, however, can be very challenging to obtain in a conventional MD simulation5 because the rugged energy landscape of this type of system causes the simulations to become trapped in local energy minima, thus preventing the simulation from sampling the entire configuration space of the system within practical simulation times. Hence, capturing the entire protein adsorption behavior requires either extremely long simulations (hundreds of microseconds or longer), or the use of an advanced sampling method to accelerate the sampling process. While previously developed accelerated sampling methods, such as replica-exchange molecular dynamics (REMD)61,62 and metadynamics,63 are extremely effective for relatively small molecular systems (e.g., small peptide folding and adsorption simulations),24,64 both REMD and metadynamics become excessively computationally expensive and inefficient for large molecular systems. For example, since the number of replicas needed for an REMD simulation scales with the square root of the size of the system, REMD would require an excessively large number of replicas for the simulation of protein adsorption behavior on a material surface. Similarly, because of the enormity of the phase space that must be sampled, the application of metadynamics for the simulation of protein adsorption behavior would be extremely inefficient and impractical as well.

To address this limitation, Latour et al.65 developed TIGER2 as an efficient type of replica-exchange simulation, which implements features similar to the “Smart Walking” sampling algorithm, which was previously developed by Zhou and Berne.66 Further studies, however, revealed that TIGER2 was only effective when used with implicit solvation (i.e., solvation energy calculated using a mean-field approximation). An updated version of this method was subsequently developed for use with systems using explicitly represented solvent, which was called TIGER2A (TIGER2 with solvent-energy Averaging).11,67,68 This method essentially decouples the number of replicas that must be used from the size of the system, thus enabling large molecular systems to be simulated more efficiently and with a smaller number of replicas than required by conventional REMD, hence dramatically reducing computational cost.

While several groups have reported on simulations of peptide interactions with material surfaces using various force fields and advanced sampling methods,69–80 relatively few studies have applied such methods for the more complex problem of the simulation of actual protein adsorption behavior. Previously conducted simulations of protein–surface interactions have primarily used regular MD simulations to predict the protein adsorption behavior;53,81–84 however, as introduced above, there are several disadvantages of the application of brute-force MD in the simulations of such a large molecular system. First, the protein in a regular MD simulation tends to become trapped in a metastable state near the original orientation on the surface, often resulting in a false impression of convergence because the simulation looks to be no longer changing. However, this is simply due to the molecular system being stuck in a state with large energy barriers separating it from other states with potentially lower free energy. Second, while standard MD simulations starting from several different initial orientations of the protein on the surface can provide a range of different adsorbed states, there is then no basis to assess which adsorbed state is preferred over the others. Third, regular MD does not provide a means to quantitatively assess the degree of convergence of the simulation system.

In this study, we present methods to addresses each of these limitations in the simulation of protein adsorption through the application of TIGER2A advanced sampling to generate a Boltzmann-weighted ensemble of adsorbed protein states. Additionally, since previously conducted simulations of protein–surface interactions had no means to calculate the most likely conformations and orientations of the protein on the surface, we employ our previously developed cluster analysis procedure85 to identify similar groups of the sampled states of the adsorbed protein, with their probabilities of occurrence then used to calculate relative free energies between the identified conformational states.

Additionally, in this work, we describe simulations of the adsorption behavior of hen egg-white lysozyme [HEWL, 14.4 kDa, PDB ID: 1GXV (Ref. 86)] on a (110) surface plane of HDPE using the TIGER2A algorithm and the tuned-IFF parameter set to represent interfacial interactions between the amino acid residues of the protein and the HDPE surface.58 The results of these simulations are compared with the adsorbed protein conformation and orientation data set that has been generated in our experimental studies of adsorption of these proteins, using such experimental techniques as CD spectropolarimetry,35 AAL/MS,36 and adsorbed-state bioactivity assays; the results of which are published elsewhere.30,37,87 These comparisons are then used to assess whether the tuned-IFF parameter set enables the orientation and conformational behavior of the protein on the surface to be more accurately predicted by the simulation compared to the use of the standard CHARMM FF.

Since simulations provide molecular-level information beyond what can be presently obtained by experiment, additionally we provide the results of various analysis methods to further assess the conformation and orientation of the adsorbed protein. Moreover, we assess the efficiency of the TIGER2A sampling method in comparison with regular MD when applied in the simulation of protein adsorption behavior.

Thus, the main objective of this work was to demonstrate the combined application of our previously developed methodologies (i.e., advanced sampling, cluster analysis, and tuned interfacial force field) for the prediction of adsorption behavior of a protein on a material surface using molecular simulations. We also present a new method that we have developed to assess the difference in free energy between different adsorbed states of the protein and a new method for assessing the degree of convergence that has been reached for a given amount of sampling. In addition, we present various methods for analyzing conformation and orientation of the adsorbed protein based on the results provided by clustering analysis, with comparison of these values to experimentally measured values for this same protein–surface system.

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS

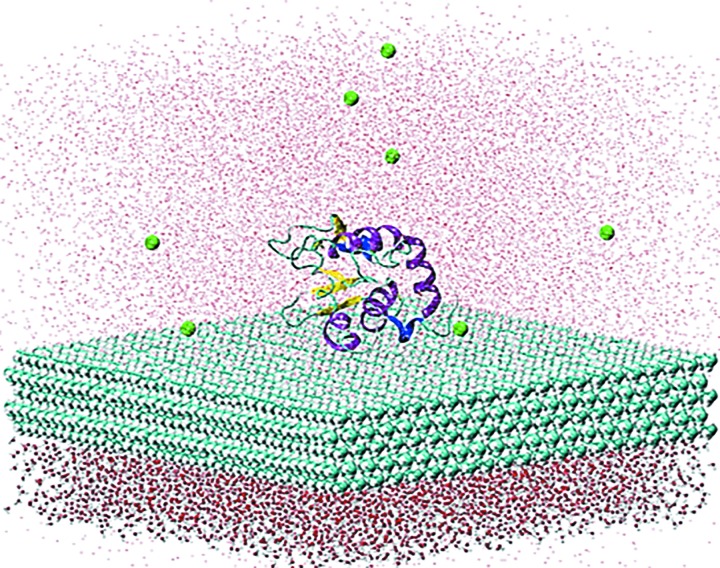

A. Design of the molecular system

The design of the protein–surface systems was similar to the peptide-surface systems used in our interfacial force field parameterization study,58 but with a much larger simulation cell in order to encompass the protein as compared to the prior nine-residue peptide. PDB ID 1GXV (Ref. 86) was used as a model of the HEWL protein in our simulation. Molecular models were constructed in TIP3P water56 (with 8 Cl− counterions added for system neutrality) over a (110) HDPE surface plane with 3-D periodic boundary conditions (PBCs) applied to represent condensed-phase conditions. The HDPE surface extended for ∼100 Å in both the x- and y-directions, which is approximately twice the length of the protein in its native folded state. Preliminary studies showed this to provide sufficient surface area for the protein to unfold partially and adsorb on the surface during the simulations. Because the simulations were performed using 3D PBCs, CHARMM PATCH commands were applied for creating covalent bonds, bond angles, and dihedral angles crossing the boundary between the primary and image cells to represent an infinite HDPE surface. Since PBCs were used, as with our previous peptide simulations, an equilibrated water layer of 15 Å in depth was placed on the bottom of the HDPE surface and kept rigid during simulations to avoid the protein adsorbing to the opposite side of the HDPE surface (Fig. 1). We understand that such a rigid water layer is likely to lead to the formation of an interfacial layer in the mobile water next to the rigid water layer. Although this interfacial mobile water layer can be expected to be less perturbed than it would be if it were adjacent to the HDPE surface itself, it still could have properties different from bulk water. In the construction of our simulation systems, we therefore provided a layer of 15–20 Å of mobile water in between the closest atom of the protein and the bottom of this rigid water layer to represent the protein in aqueous solution over the HDPE surface. In the assembled systems, the initial height of mobile solution phase (consisting of the protein, water, and counterions) was ∼55 Å in the z dimension. The height of the solution phase of the systems was adjusted to provide 1 atm pressure in the solution phase of the system.88 Evaluation of the solution phase pressure of a protein-HDPE system with different folded and unfolded states of the protein under constant volume conditions determined that the pressure change upon unfolding of the protein is statistically insignificant, which indicated that the pressure could be kept at a constant value of about 1 atm independent of its state of unfolding during the simulation.

Fig. 1.

Representative model system for simulations with HEWL on the HDPE surface. The protein is displayed in cartoon representation, fixed water layer bellow the HDPE surface by ball-and-stick representation, and the HDPE surface and Cl− counterions by vdW surface representation. The mobile water layer is shown in points for clarity. The graphical representation was generated using VMD (Ref. 89).

B. TIGER2A enhanced sampling versus regular MD and tuned IFF versus CHARMM FF for the interfacial interactions

To compare the efficiency of the TIGER2A algorithm with the regular MD simulations, each system was simulated using both the TIGER2A replica exchange advanced sampling method and regular MD. As a control, a system of the protein in solution (without the presence of the surface in the simulation system) was also simulated using both methods in order to assess whether the conformational change of the protein during the simulations was due to some inherent instability of the folded protein structure or due to the interactions of the HDPE surface with the protein. Additionally, to evaluate the capability of the tuned IFF parameters58 to more appropriately represent the orientation and conformation of the protein on the surface, each protein-surface system was constructed and simulated using two different sets of parameters for the interfacial interactions—the CHARMM22/CMAP FF (Ref. 56) and our tuned IFF.58 Because our interfacial force field parameterization for HDPE was conducted using the CHARMM22 FF parameter set90 including CMAP cross-terms,91 in the current study, these FF parameters were used for the interfacial interactions in the simulations using this CHARMM FF. The default CHARMM22/CMAP FF was also used for representing the interactions of the protein with the surrounding water and ions in the aqueous solution.

The total series of simulations included a set of five regular MD simulations and four TIGER2A simulations to enable comparisons to be made between these different sampling methods. The regular MD simulations included: (1) HEWL in solution, (2) two systems each with a distinct orientation of HEWL on the HDPE surface using the CHARMM FF, and (3) two systems each with a distinct orientation of the protein on the surface using the tuned IFF. All regular MD simulations were performed at 300 K. The TIGER2A simulations included: (1) HEWL in solution, (2) one system of HEWL over the HDPE surface using the CHARMM FF, and (3) two independent simulations of HEWL over the HDPE surface using the tuned IFF.

Each TIGER2A simulation of HEWL on HDPE was run with eight replicas, with each replica having a different orientation of the protein over the surface to enhance sampling. For each orientation, the HEWL was positioned with its long axis parallel to the material surface plane with its distance from the surface plane set such that its closest atom was 1 Å away from the surface. The orientations differed in the rotation of the protein about this long axis.

The eight temperature replicas in the TIGER2A simulations were uniformly spaced from 300 K to 660 K. The upper temperature limit was determined from preliminary 10 ns simulations of the protein at different elevated temperature levels ranging from 300 to 720 K with 30 K intervals to generate a protein melting curve as designated by the protein's secondary structure composition. From these preliminary studies, it was determined that HEWL underwent full unfolding (i.e., complete loss of helical and sheet structure) at 660 K over this timeframe.

To provide convergence statistics, we performed two independent instances of the TIGER2A simulations of the protein–surface system using the tuned IFF for the interfacial interactions as described above. These two seeds differed from each other in three ways: (1) the orientation of the protein on the surface for each replica, (2) the pseudorandom number seed for the atomic velocities, and (3) the pseudorandom number seed for the Metropolis criterion evaluation used for replica exchange. At the end of the simulations the ensembles of states obtained from these two independent simulations were merged. This merged ensemble of states was then clustered according to the cluster analysis procedure described in Sec. II C 2 b. The degree of convergence between these two simulations for each obtained cluster then was calculated by Eq. (1)

| (1) |

where and are the probabilities of the states from simulation 1 and simulation 2, respectively. This expression reflects the deviation from the expected equilibrium composition of 50%.

All simulations were conducted in the LAMMPS molecular simulation program, including the addition of CMAP cross-terms.57 For each molecular system, simulations were performed for 100 ns in the canonical ensemble using Nosé-Hoover thermostat92 and 2 fs timestep enabled by using SHAKE algorithm93 to constrain bonds involving hydrogens. Electrostatic interactions used 12 Å cutoffs with force-shifting and van der Waals interactions used 8–12 Å force-switching cutoffs. The length of the TIGER2A simulation cycle was 1.0 ns, with each cycle composed of 500 ps heating and sampling at the designated replica temperature, 400 ps quenching and sampling at the baseline temperature (300 K), and 100 ps of solvent-energy averaging.68 All heavy atoms of the material surface were position constrained during all simulations. Since the aim of the study was to sample the adsorbed state of the protein, in order to avoid the desorption of the protein (which was especially relevant in our TIGER2A simulations for replicas that were run at high elevated temperatures), and to ensure the sampling of adsorbed protein states, the protein was harmonically restrained in a way that the closest protein atom to the surface was not allowed to move more than 5 Å away from the surface plane.

It must be pointed out that TIGER2A is an REMD method that generates an ensemble average of states as opposed to an actual dynamic time sequence. Thus, these simulations do not represent 100 ns of continuous MD, but rather 100 ns of sampling. By design, the elevated temperature levels used in this sampling algorithm provide additional thermal energy to rapidly cross energy barriers, which enables an equilibrated system of states to be sampled much more quickly than by a conventional MD simulation.

C. Analysis of the simulation results

1. Comparison with experimental results

The trajectories obtained by the regular MD simulations and the ensembles of states obtained by the TIGER2A simulations for each molecular system were analyzed to calculate average parameters that cannot only be directly compared with the experimental results,37 but can also provide supplemental molecular-level information on protein adsorption, which cannot be determined by the experiment alone. One such simulation parameter that can be directly correlated with experimental values is the secondary structure content of the protein in its adsorbed states, which assesses the conformation of the adsorbed protein. Another such parameter, which can be readily calculated in the simulation and compared with the experiment, is the solvent accessible surface area (SASA) of individual protein residues in the adsorbed state of the protein relative to its solution state. An increase in SASA designates an unfolding of the protein to increase the solvent exposure of a given amino-acid residue and a decrease in SASA designates a loss in solvent accessibility of a specific residue either due to the residue being adsorbed on the HDPE surface or possibly a folding event causing the residue to be buried within the protein. While a simulation provides SASA results of the entire range of residues in the protein, comparison between simulation and experiment is limited to only those residues which have been experimentally labeled, to assist in mass spectrometric analysis of SASA. In our previously published experimental data, these residues for HEWL were as follows: K1, R5, E7, K13, R14, D18, R21, W28, K33, E35, R45, D48, D52, R61, W62, W63, D66, R68, R73, D87, K96, K97, D101, W108, W111, R112, R114, K116, D119, W123, R125, and C128.87

Similar to the experiment, in simulation the solvent accessible “Profile” for each amino-acid residue was calculated through the following expression:

| (2) |

where is the SASA of the amino-acid residue in the adsorbed state of the protein, and is the SASA of the residue in the native state of the protein in solution. If the SASA of a given amino-acid residue in the native state in solution or in its adsorbed states was found to be less than 0.1 Å2, then a low ceiling threshold value of 0.1 was designated for the respective value instead of 0 in order to avoid the mathematical error of either dividing by zero or taking the log of 0 in Eq. (2). CHARMM's COOR (Ref. 56) facility was used to calculate the SASA in simulation (with the radius of the probe rolling over the protein's vdW surface designated to be 1.4 Å).

2. Assessment of adsorbed protein conformation

Two parameters were calculated in order to assess the conformation of the adsorbed protein in the simulation—the secondary structure content of the protein and the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) from the native state of the protein. The RMSD calculations compared the Cα atoms of the protein after simulation with respect to its native state structure. The secondary structure content (% helix, % sheet) was calculated using the DSSP algorithm.94 Both the RMSD and DSSP calculations were performed in MDTraj.95

a. Assessment of the adsorbed protein orientation

The orientation of the adsorbed protein on the HDPE surface was characterized by the angle (Θ) between a vector describing the position of the adsorbed protein and the surface outer normal vector. The position vector for the protein was defined as the cross-product of the two vectors defined by the position of the N and C termini of the protein relative to the protein's center of gravity (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Graphical description of the angle of the adsorbed protein relative to the material surface (Θ°). The angle was defined as the angle between the protein vector (vector N × C) and the surface normal (vector n). The protein vector was calculated as the cross-product of two vectors, both of which start from center of mass of the protein and pass through N-terminus (vector N) or C-terminus (vector C).

Additionally, the height of each amino-acid residue (e.g., Cα atoms) above the material surface can provide important information on the orientation of the adsorbed protein (see Fig. S1 in supplementary material).96 This data can be used to determine the preferential orientation of the protein on the surface by studying the protein residues that have the highest affinity to the surface (i.e., those located closest to the surface and thus interacting most strongly with it).

b. Cluster analysis

To determine the preferred conformations as well as orientations of the protein adsorbed on the surface, cluster analysis of the ensembles of states obtained from TIGER2A sampling was performed following the cluster analysis procedure described in Abramyan et al.85 According to the clustering procedure, the optimal number of clusters was determined from the consensus of 12 combinations of different cluster analysis and validation algorithms. Four different clustering algorithms (single-linkage,97 complete-linkage,98 average-linkage,99 and Ward's method100) were used to group the ensembles of states generated in the TIGER2A simulations for each of the protein–surface systems. For each obtained clustering, three different cluster validation techniques (Calinski-Harabasz,101 Davies-Bouldin,102 and silhouette103 indices) were used. Based on the combined results of these methods, the consensus number of clusters was determined (see Fig. S2 in supplementary material). Subsequently, the Cα values of the three most populated clusters were calculated, and the clustering algorithm that provided the clusters with the lowest values of the Cα was selected as the best clustering solution. In these simulations, this was Ward's clustering algorithm, the results of which were then used for the analysis of the clusters for each TIGER2A simulation (see Table S1 in supplementary material).

Additionally, for these best clustering solutions, the free energies of each cluster relative to smallest cluster () were calculated by their relative probability of occurrence using the equation

| (3) |

where R is the gas constant in kcal mol−1 K−1, T is the baseline temperature of 300 K, is the number of frames (states) present in the cluster for which is being calculated, and is the number of frames (states) in the smallest cluster with the given clustering results. The standard deviation for the number states in each cluster was also calculated (see Table S2 in supplementary material). For the seven most populated clusters, the conformation and orientation of the protein were also assessed as described above.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We emphasize that the key objectives of this research were to demonstrate the need for the application of advanced sampling methods (e.g., TIGER2A) compared to conventional MD methods for the simulation of complex systems like protein adsorption, and to present a method to assess the degree of convergence that is reached for a given amount of sampling. To our knowledge, no previous study has been published that presents a quantitative method to assess the degree of convergence of such simulations. Simulations of protein adsorption behavior involving a protein of the size of lysozyme have never been shown to be carried out to convergence. In fact actual convergence of such a system would most likely require orders-of-magnitude longer simulations, which is to-date prohibitively expensive. One of the key features of our study was, by using our previously developed cluster analysis method, to demonstrate a method to measure convergence of such simulations. Additionally, through correlations with experiment, we evaluated the capability of our previously developed tuned interfacial force field to predict the protein adsorption behavior compared with the standard CHARMM force field. Various methods of analysis of conformation and orientation of the adsorbed protein are also presented.

A. TIGER2A simulations versus regular MD

The results from the cluster analyses of the trajectories obtained in the regular MD simulations of HEWL adsorption on the HDPE surface show that the protein starting with two different orientations over the surface resulted in the protein in each case settling into an adsorbed position that was very close to its initial orientation, and essentially staying in that state for the entire 100-ns simulation. As shown in Fig. 3(a), the top five clusters from these simulations identify conformations and orientations that are extremely similar to each other. However, the apparent convergence due to the appearance of a final “stable” state is purely artefactual. These results demonstrate the inherent problem with regular MD in that simulations that start with different orientations of the protein on the surface will result in different final structures without any means of assessing which is the more likely result. A TIGER2A simulation overcomes this problem by starting from a broad range of initial configurational states, and by using a broad range of elevated temperatures to more efficiently cross large energy barriers that separate different states of the system. As shown in Fig. 3(b), TIGER2A sampling is thus able to sample a wide distribution of states with Boltzmann weighting between them, with cluster analysis identifying several distinctly different conformations and orientations and then providing a means of assessing their probability of occurrence and for the calculation of the difference in free energy between them.

Fig. 3.

Representative states from the top five most populated clusters obtained in 100 ns of sampling (for each simulation) of HEWL on HDPE (a) using standard MD starting from two distinct orientations of the protein on the surface, and (b) using TIGER2A advanced sampling using eight replicas, each starting with a different orientation of the protein on the surface.

B. Comparison with experimental results

One parameter that can be readily calculated from the simulation and correlated with the experimental results is the secondary structure content of the adsorbed protein, which is a way to assess adsorption-induced changes in protein conformation. The results of the secondary structure content of the adsorbed HEWL protein from simulation and experiment87 are provided in Table I. The results of the simulations of the protein in aqueous solution are also presented as a control. Naturally, the protein in solution at room temperature without the influence of any material surface should remain in its native state with only minor deviations from the original PDB structure. These results show that experimentally HEWL decreased its helical content by 16% (38% → 22%) and increased its sheet content by 12% (16% → 28%) on HDPE. In the regular MD simulations with either the CHARMM FF or IFF, however, the helicity and sheet secondary structure content of the adsorbed protein relative to the simulation of the protein in aqueous solution changed by about 1% or less. This analysis indicates, again, that the MD simulation remains kinetically trapped in a local minimum for the duration of the simulations. The TIGER2A simulation with the CHARMM FF also resulted in changes in the helicity and sheet content by only about 1%. This stability can be attributed to the potential, rather than a lack of sampling, because the results are quite different when the tuned IFF is used with TIGER2A sampling. This is also consistent with the finding by Shaw et al. that the CHARMM FF tends to overly stabilize protein helical structure, compared to experiment.104,105 The TIGER2A simulations using the tuned IFF for the interfacial interactions58 resulted in changes more in the direction of the experimental results, with a decrease in helicity of 5.6% (40.1% → 34.5%) and an increase in sheet content by 5.3% (3.5% → 8.8%). While the relatively large standard deviations prevent these changes from being attaining statistical significance, these results do indicate that the trends exhibited by the TIGER2A IFF simulations were more consistent with the observed experimental behavior of this system than simulations using MD or the CHARMM FF. In addition, the larger standard deviations obtained from TIGER2A sampling compared to the regular MD simulations reflect the greater degree of sampling provided by this advanced sampling method compared to the much more limited degree of sampling provided by conventional MD sampling.

Table I.

Assessment of the secondary structure content of HEWL protein between simulation and experimental results (Ref. 87). The results of the simulations are ensemble averages. All values are given as average (standard deviation).

| System |

Secondary structure content (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Helices | Sheets | |

| Native (PDB ID: 1GXV) | 37.2 | 7.0 |

| Experiment | ||

| In solution | 38 (0.8) | 16 (0.8) |

| On HDPE surface | 22 (1.2) | 28 (1.2) |

| Regular MD simulations | ||

| In solution | 35.2 (3.2) | 10.6 (1.0) |

| On HDPE surface | ||

| CHARMM FF (both orientations) | 36.3 (3.1) | 10.7 (0.8) |

| Tuned IFF (both orientations) | 35.5 (2.7) | 10.5 (1.0) |

| TIGER2A simulations | ||

| In solution | 40.1 (6.0) | 3.5 (3.1) |

| On HDPE surface | ||

| CHARMM FF | 39.1 (4.3) | 4.8 (3.7) |

| Tuned IFF (both seeds) | 34.5 (6.3) | 8.8 (3.2) |

Another parameter that can be readily calculated in the simulation and compared with the experiment is the SASA profile of the protein residues (SASA in the adsorbed state of the protein relative to its solution state). Changes in SASA after adsorption are influenced by both the orientation and tertiary unfolding of the protein. As Fig. 4 shows, the solvent accessibility profiles for the CHARMM FF and the tuned IFF differ are quite similar overall but with some substantial differences. Comparison with experimental values indicate that the tuned IFF is able to more closely reproduce the experimental observations for a targeted set of amino-acid residues, as indicated by the substantial increase in the R correlation coefficient between simulation and experiment for the tuned IFF compared to the CHARMM FF. Some obvious increase or decrease in the solvent accessibility of residues in certain regions of the protein can be observed. Figure 4 also highlights the solvent accessibility profiles of the active site residues of HEWL. The behavior (conformation and orientation) of the active site residues in the adsorbed protein can be of high significance due to its potential influence on the bioactivity of the protein.

Fig. 4.

(a) Ensemble average SASA profiles for the entire sequence of the protein are shown. The SASA profiles of the active site residues, E35 and D52, are also highlighted. The correlation between simulation and experimental SASA profiles of selected amino-acid residues is displayed on the right-hand side. (b) The active site residues in the native state and in the adsorbed state of the protein are shown. The adsorbed states are representative conformations from the top cluster in the TIGER2A simulations for the CHARMM FF and the tuned IFF for interfacial interactions.

C. Cluster analysis

The ensembles of adsorbed protein states obtained in the TIGER2A simulations using the CHARMM FF and the tuned IFF for the interfacial interactions were subjected to cluster analysis following our previously developed methodology.85 In comparison with the regular MD simulations in which the protein is unable to escape one single metastable state to sample other conformations and orientations of the protein on the surface, TIGER2A provides a much broader sampling of the adsorbed states. Using this enhanced sampling algorithm we could assess a distribution of the sampled adsorbed states, the free energy differences between them based on the population of the different clusters, and eventually predict the lowest of the given protein-adsorption system. The number of sampled states and of the obtained clusters are provided in Fig. 5. In addition, the standard deviations of the number of states in each cluster are provided in Table S2 in supplementary material.

Fig. 5.

Number of sampled states in each cluster (dark gray columns and above numbers, left-hand axis) and the relative free energies of each cluster (light blue columns, right-hand axis) of the adsorbed protein states obtained in TIGER2A enhanced sampling simulations using the CHARMM FF and the tuned IFF for the interfacial interactions.

The representative adsorbed protein states from the two most populated clusters for each protein-surface system in the TIGER2A simulations are provided in Fig. 6. For these representative states, the amino-acid residues found within 5 Å from the surface, which can be considered to mediate the adsorption process, are indicated in Table II. These data show that the top two clusters for each simulation system provide distinctly different orientations of the protein on the surface, especially between the CHARMM and tuned the IFF simulations. Examination of these closely adsorbed residues shows that 0% of the residues from the CHARMM FF simulation were found in the tuned IFF seed 1 or 2 simulation results for cluster 1 and only 25% (5 out of 20 residues) for cluster 2. In contrast, comparison between the seed 1 and seed 2 results for the tuned IFF simulations show 29% agreement (4 out of 14 residues) for cluster 1 and 57% agreement (13 out of 23 residues) for cluster 2. These comparisons thus reflect the differences in the protein adsorption behavior predicted by these two different interfacial force fields and suggest a level of convergence for the two independent seeds for the tuned IFF TIGER2A simulations.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of the predicted adsorption behavior of HEWL protein on HDPE in TIGER2A simulations using the CHARMM FF and the tuned IFF (seed 1 and seed 2) for the interfacial force field. Representative states from the two most populated clusters are displayed. On the top of each figure the overall orientation of the protein is shown; followed with the images framed in black, which highlight the residues found within 5 Å from the surface (i.e., residues predicted to directly interact with the surface). The bottom images show the residues interacting with the surface, as viewed from below the surface.

Table II.

Protein residues found within 5 Å from the surface in the representative adsorbed protein states in the top two clusters as displayed in Fig. 6.

| Cluster number | CHARMM FF |

Tuned IFF |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Seed 1 | Seed 2 | ||

| Cluster 1 | K1, K13, R14, H15, R68, T69, P70, C76, I78, P79, A82, L83, S85, S86, D87, T89, A90, N93, K96, K97 | T47, D48, R61, W62, S72, R73, G102, N103, A107, W111, N106, R112, N113, K116 | T47, R112, N113, R114, K116, T118, Q121 |

| Cluster 2 | N65, D66, R68, T69, P70, R73, N74, L75, N77, P79, S81, K97, I78 | Y23, T47, D48, G49, S50, R61, W62, T69, P70, G71, S72, R73, N93, D101, G102, N103, G104, M105, N106, A107, W108, V109, A110 | R21, Y23, T47, D48, G49, R61, W62, W63, P70, S72, R73, G102, N103, N106, A107, R112, N113 |

By conducting two independent replica exchange simulations, we also provide a second quantitative means of assessing the degree of convergence that is obtained after a given length of simulation. This measure of convergence can be provided by first merging the data from the tuned-IFF seed 1 and seed 2 simulations together, and then clustering this combined pool of sampled states. In the resulting clusters we then calculate the percent of states from seed 1 and states from seed 2 (Fig. 7), with the assumption that if full convergence was reached in both the seed 1 and 2 simulations, then each of the resulting clusters would have approximately even contribution from each seed (i.e., 50% from seed 1 and 50% from seed 2). The percent convergence can then be estimated by the degree in which the contributions from seed 1 and 2 deviate from this theoretical even distribution [Eq. (1)]. Following this approach, the convergence percentages from cluster 1 to cluster 8 were determined to be 50.0%, 18.2%, 74.6%, 15.4%, 9.5%, 25.0%, 0%, and 0%, respectively. Although these convergence data indicate that longer simulations are needed in order to reach full convergence between the simulation seeds, the relatively good convergence of the first and third most populated clusters show that the simulations have begun to reach a moderate level of converge. Indeed, it is quite encouraging that the sampling from each of the independent simulations is broad enough to have found configurations that are among the six most populated states.

Fig. 7.

Assessment of the convergence between seed 1 and seed 2 in TIGER2A simulations of HEWL on HDPE using tuned IFF for the interfacial interactions. The simulation seeds were merged and cluster analysis was run on this merged ensemble of states, which identified eight clusters. The percent of states from each seed was then calculated for each cluster. The convergence percentages from cluster 1 to cluster 8 are 50.0%, 18.2%, 74.6%, 15.4%, 9.5%, 25.0%, 0%, and 0%, respectively.

D. Assessment of the adsorbed protein conformation and orientation

As a means of characterizing the conformation and orientation of HEWL on the HDPE surface, Table III presents the TIGER2A simulation results for the adsorbed protein conformation (secondary structure and RMSD) and the adsorbed protein orientation (average angle between the protein's position vector and the outer normal to the surface) for each of the top seven clusters for the CHARMM FF and the tuned IFF. As clearly evident from the values shown, the use of the tuned IFF parameter set results in substantially different results for both the adsorbed protein conformation and orientation on the surface compared to the CHARMM FF. And, as shown from Table I, the overall trends in the changes of secondary structure elements from the tuned IFF TIGER2A simulation align more closely to the experimental observed behavior than the results from the CHARMM FF.

Table III.

Assessment of protein conformation and its orientation on the surface for the top seven clusters of the adsorbed protein in TIGER2A simulations using the CHARMM FF and the tuned IFF (both seeds combined) for the interfacial interactions. All values are given as average (95% confidence interval).

| Cluster number |

CHARMM FF |

Tuned FF (both seeds) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Conformation of adsorbed protein |

Conformation of adsorbed protein |

|||||||

|

Secondary structure content (%) |

RMSD (Å) | Orientation of adsorbed protein Θ (deg) |

Secondary structure content (%) |

RMSD (Å) | Orientation of adsorbed protein Θ (deg) | |||

| Helices | Sheets | Helices | Sheets | |||||

| 1 | 38.5 (11.5) | 0.9 (4.4) | 13.1 (1.0) | 21.7 (25.3) | 37.2 (11.6) | 9.8 (4.0) | 2.5 (1.2) | 74.7 (22.0) |

| 2 | 42.6 (16.8) | 5.3 (0.4) | 12.6 (1.5) | 30.9 (60.8) | 35.7 (13.0) | 9.9 (8.9) | 2.1 (3.6) | 27.1 (28.9) |

| 3 | 37.9 (16.2) | 7.4 (0.5) | 12.2 (0.5) | 28.0 (29.3) | 36.8 (13.4) | 9.4 (7.4) | 12.5 (1.4) | 95.8 (86.1) |

| 4 | 34.3 (9.5) | 10.4 (0.6) | 12.3 (0.7) | 55.3 (24.3) | 33.3 (14.0) | 9.8 (9.7) | 3.0 (6.1) | 47.8 (56.2) |

| 5 | 35.0 (5.7) | 11.1 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.5) | 17.1 (12.2) | 27.2 (19.7) | 1.9 (5.4) | 14.2 (2.6) | 147.7 (119.7) |

| 6 | 39.1 (7.0) | 0 | 7.7 (1.2) | 106.0 (126.0) | 29.0 (27.5) | 4.8 (16.8) | 12.8 (2.9) | 33.7 (56.2) |

| 7 | 39.5 (5.0) | 0 | 11.4 (0.6) | 80.8 (22.1) | 18.0 (13.5) | 0 | 16.5 (1.2) | 16.6 (29.4) |

Figure 8 provides the distributions of RMSD and the orientation angles for the complete ensemble of states obtained with TIGER2A with the results from the standard MD simulations; both using the tuned IFF. As clearly shown here, the standard MD simulations provide quite narrow distributions compared to the TIGER2A distributions, thus further showing the much broader sampling and phase-space coverage that this provided by TIGER2A.

Fig. 8.

Probability densities of the adsorbed protein's Cα RMSD from the crystal structure characterizing the adsorption-induced change in conformation (top plots), and angle between the protein's position and the normal vector from the surface characterizing adsorbed orientation (bottom plot) in regular MD simulations and TIGER2A simulations, both using tuned IFF for the interfacial interactions. Regular MD simulations started from two distinct orientations of the protein on the surface, and TIGER2A simulation started from two seeds, and each seed had eight different orientations of the protein on the surface.

Finally, in addition to the assessment of the secondary structures and RMSD values per cluster provided in Table III, Fig. 9 presents the evolution of these parameters over the 100-ns sampling period. As indicated in Fig. 9, the helicity of HEWL in solution and on the HDPE surface with the tuned IFF were quite stable over the first about 80 ns, but then show substantial changes beginning to occur with no apparent plateau region thereafter. Similarly, the RMSD plots show a distinct increase around the same time. These features again indicate that new regions of phase space were just beginning to be sampled at this period of time and that longer simulations would result in better convergence.

Fig. 9.

Conformational assessment of the protein. Secondary structure content and Cα RMSD from the crystal structure of HEWL obtained over 100 ns of TIGER2A sampling are shown. The secondary structure contents were calculated for every 5 cycles, which is equivalent to 5 ns of TIGER2A.

IV. CONCLUSION

In this work we demonstrated the limited sampling of regular MD in the simulations of protein-surface interactions and its inability to compare probability of adsorbed protein states provided by differing starting orientations of the protein. In contrast, we showed that TIGER2A sampling allows for the broader coverage of the configuration space of the molecular system, with cluster analysis then enabling relative free energies to be calculated for different adsorbed protein states with their respective conformations and orientations on the surface. Additionally, it was shown that using the tuned IFF derived in our previously conducted parameterization studies provides trends that are in closer agreement with experimental results than using CHARMM FF for interfacial behavior. To understand whether the simulations had converged, we also present a method to quantitatively assess the degree of convergence, which indicates that even longer simulation times than 100 ns are needed before TIGER2A simulations for the system presented can be considered to have converged. Finally, we showcased a handful of ways in which the protein-adsorption simulation data can be analyzed to then be correlated with the experiment or to serve as supplemental molecular-level information not observed in experiment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project received support from the Defense Threat Reduction Agency-Joint Science and Technology Office for Chemical and Biological Defense (Grant No. HDTRA1-10-1-0028), NIH NIGMS IDeA grant P20GM103444, and Department of Bioengineering of Clemson University. Computing resources: Palmetto Linux Cluster, Clemson University. The authors would also like to acknowledge the computational cluster support received by Corey Ferrier and Marcin Ziolkowski.

References

- 1. Gray J. J., Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14 110 (2004). 10.1016/j.sbi.2003.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roach P., Farrar D., and Perry C. C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 8168 (2005). 10.1021/ja042898o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang Z., Zhang M., Chen S., Horbett T. A., Ratner B. D., and Jiang S., Biomaterials 29, 4285 (2008). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rabe M., Verdes D., and Seeger S., Adv. Colloid Interfaces 162, 87 (2011). 10.1016/j.cis.2010.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Latour R. A., Colloid Surf. B 124, 25 (2014). 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.06.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lutolf M. and Hubbell J., Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 47 (2005). 10.1038/nbt1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stevens M. M. and George J. H., Science 310, 1135 (2005). 10.1126/science.1106587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wilson C. J., Clegg R. E., Leavesley D. I., and Pearcy M. J., Tissue Eng. 11, 1 (2005). 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Salvador-Morales C., Flahaut E., Sim E., Sloan J., Green M. L. H., and Sim R. B., Mol. Immunol. 43, 193 (2006). 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Almeida A. J. and Souto E., Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 59, 478 (2007). 10.1016/j.addr.2007.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pinholt C., Hartvig R. A., Medlicott N. J., and Jorgensen L., Expert Opin. Drug Delivery 8, 949 (2011). 10.1517/17425247.2011.577062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Amanda A., Kulprathipanja A., Toennesen M., and Mallapragada S. K., J. Membr. Sci. 176, 87 (2000). 10.1016/S0376-7388(00)00433-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Przybycien T. M., Pujar N. S., and Steele L. M., Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 15, 469 (2004). 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Park H.-Y., Schadt M. J., Wang L., Lim I. I., Njoki P. N., Kim S. H., Jang M.-Y., Luo J., and Zhong C.-J., Langmuir 23, 9050 (2007). 10.1021/la701305f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen R. J., Choi H. C., Bangsaruntip S., Yenilmez E., Tang X., Wang Q., Chang Y.-L., and Dai H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 1563 (2004). 10.1021/ja038702m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ohno Y., Maehashi K., Yamashiro Y., and Matsumoto K., Nano Lett. 9, 3318 (2009). 10.1021/nl901596m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lazzara T. D., Mey I., Steinem C., and Janshoff A., Anal. Chem. 83, 5624 (2011). 10.1021/ac200725y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sapsford K. E., Bradburne C., Delehanty J. B., and Medintz I. L., Mater. Today 11, 38 (2008). 10.1016/S1369-7021(08)70018-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Feltis B., Sexton B., Glenn F., Best M., Wilkins M., and Davis T., Biosens. Bioelectron. 23, 1131 (2008). 10.1016/j.bios.2007.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Uttamchandani M., Neo J. L., Ong B. N. Z., and Moochhala S., Trends Biotechnol. 27, 53 (2009). 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Herr A., Microarrays, edited by Dill K., Liu R., and Grodzinski P. ( Springer, New York, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kalb S. R. and Barr J. R., Anal. Chem. 81, 2037 (2009). 10.1021/ac802769s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Periyakaruppan A., Arumugam P. U., Meyyappan M., and Koehne J. E., Biosens. Bioelectron. 28, 428 (2011). 10.1016/j.bios.2011.07.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Deighan M. and Pfaendtner J., J. Langmuir 29, 7999 (2013). 10.1021/la4010664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Latour R. A., Biointerphases 3, FC2 (2008). 10.1116/1.2965132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zoungrana T., Findenegg G. H., and Norde W. J., Colloid Interface Sci. 190, 437 (1997). 10.1006/jcis.1997.4895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fears K. P. and Latour R. A., Langmuir 25, 13926 (2009). 10.1021/la900799m [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sivaraman B., Fears K. P., and Latour R. A., Langmuir 25, 3050 (2009). 10.1021/la8036814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sivaraman B. and Latour R. A., Biomaterials 31, 832 (2010). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wei Y., Thyparambil A. A., and Latour R. A., Colloid Surf. B 110, 363 (2013). 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wei Y., Thyparambil A. A., and Latour R. A., BBA-Proteins Proteomics 1844, 2331 (2014). 10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mrksich M., Sigal G. B., and Whitesides G. M., Langmuir 11, 4383 (1995). 10.1021/la00011a034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Green R. J., Frazier R. A., Shakesheff K. M., Davies M. C., Roberts C. J., and Tendler S. J., Biomaterials 21, 1823 (2000). 10.1016/S0142-9612(00)00077-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wei Y. and Latour R. A., Langmuir 24, 6721 (2008). 10.1021/la8005772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wei Y. and Latour R. A., Langmuir 25, 5637 (2009). 10.1021/la8042186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fears K. P., Sivaraman B., Powell G. L., Wu Y., and Latour R. A., Langmuir 25, 9319 (2009). 10.1021/la901885d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thyparambil A. A., Wei Y., Wu Y., and Latour R. A., Acta Biomater. 10, 2404 (2014). 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wei Y., Thyparambil A. A., Wu Y., and Latour R. A., Langmuir 30, 14849 (2014). 10.1021/la503854a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim D. T., Blanch H. W., and Radke C. J., Langmuir 18, 5841 (2002). 10.1021/la0256331 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schön P., Görlich M., Coenen M. J. J., Heus H. A., and Speller S., Langmuir 23, 9921 (2007). 10.1021/la700236z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Foose L. L., Blanch H. W., and Radke C. J., J. Biotechnol. 132, 32 (2007). 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2007.07.954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tsapikouni T. S. and Missirlis Y. F., Mater. Sci. Eng. B 152, 2 (2008). 10.1016/j.mseb.2008.06.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Le Brun A., Holt S., Shah D., Majkrzak C., and Lakey J., Eur. Biophys. J. 37, 639 (2008). 10.1007/s00249-008-0291-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wei T., Kaewtathip S., and Shing K., J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 2053 (2009). 10.1021/jp806586n [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang M., Yuan J., Huang X., Cai X., Li L., and Shen J., Colloid Surf., B 103, 52 (2013). 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Choi H. S., Liu W., Misra P., Tanaka E., Zimmer J. P., Ipe B. I., Bawendi M. G., and Frangioni J. V., Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 1165 (2007). 10.1038/nbt1340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Röcker C., Pötzl M., Zhang F., Parak W. J., and Nienhaus G. U., Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 577 (2009). 10.1038/nnano.2009.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shang L., Brandholt S., Stockmar F., Trouillet V., Bruns M., and Nienhaus G. U., Small 8, 661 (2012). 10.1002/smll.201101353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chen S., Zheng J., Li L., and Jiang S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 14473 (2005). 10.1021/ja054169u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Seitz R., Brings R., and Geiger R., Appl. Surf. Sci. 252, 154 (2005). 10.1016/j.apsusc.2005.02.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rechendorff K., Hovgaard M. B., Foss M., Zhdanov V., and Besenbacher F., Langmuir 22, 10885 (2006). 10.1021/la0621923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bittrich E., Rodenhausen K. B., Eichhorn K.-J., Hofmann T., Schubert M., Stamm M., and Uhlmann P., Biointerphases 5, 159 (2010). 10.1116/1.3530841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wei T., Carignano M. A., and Szleifer I., Langmuir 27, 12074 (2011). 10.1021/la202622s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Abramyan T. et al. , ACS Symp. Ser. 1120, 197 (2012). 10.1021/bk-2012-1120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Biswas P. K., Vellore N. A., Yancey J. A., Kucukkal T. G., Collier G., Brooks B. R., Stuart S. J., and Latour R. A., J. Comput. Chem. 33, 1458 (2012). 10.1002/jcc.22979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brooks B. R. et al. , Comput. Chem. 30, 1545 (2009). 10.1002/jcc.21287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Plimpton S., J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1 (1995). 10.1006/jcph.1995.1039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Abramyan T. M., Snyder J. A., Yancey J. A., Thyparambil A. A., Wei Y., Stuart S. J., and Latour R. A., Biointerphases 10, 021002 (2015). 10.1116/1.4916361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Snyder J., Abramyan T., Yancey J., Thyparambil A., Wei Y., Stuart S., and Latour R., Biointerphases 7, 56 (2012). 10.1007/s13758-012-0056-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Thyparambil A. A., Wei Y., and Latour R. A., Langmuir 28, 5687 (2012). 10.1021/la300315r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sugita Y. and Okamoto Y., Chem. Phys. Lett. 314, 141 (1999). 10.1016/S0009-2614(99)01123-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Liu P., Kim B., Friesner R. A., and Berne B., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 13749 (2005). 10.1073/pnas.0506346102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Laio A. and Gervasio F. L., Rep. Prog. Phys. 71, 126601 (2008). 10.1088/0034-4885/71/12/126601 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wright L. B. and Walsh T. R., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 4715 (2013). 10.1039/c3cp42921k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Li X., O'Brien C. P., Collier G., Vellore N. A., Wang F., Latour R. A., Bruce D. A., and Stuart S. J., J. Chem. Phys. 127, 164116 (2007). 10.1063/1.2780152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zhou R. and Berne B. J., Chem. Phys. 107, 9185 (1997). 10.1063/1.475210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Li X. and Latour R. A., Polymer 50, 4139 (2009). 10.1016/j.polymer.2009.06.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Li X., Snyder J. A., Stuart S. J., and Latour R. A., J. Chem. Phys. 143, 144105 (2015). 10.1063/1.4932341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hoefling M., Iori F., Corni S., and Gottschalk K.-E., Langmuir 26, 8347 (2010). 10.1021/la904765u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Monti S. and Walsh T. R., J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 22197 (2010). 10.1021/jp107859q [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Collier G., Vellore N. A., Yancey J. A., Stuart S. J., and Latour R. A., Biointerphases 7, 24 (2012). 10.1007/s13758-012-0024-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Schneider J. and Colombi Ciacchi L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 2407 (2012). 10.1021/ja210744g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Akdim B., Pachter R., Kim S. S., Naik R. R., Walsh T. R., Trohalaki S., Hong G., Kuang Z., and Farmer B. L., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 7470 (2013). 10.1021/am401731c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Meißner R. H., Schneider J., Schiffels P., and Colombi Ciacchi L., Langmuir 30, 3487 (2014). 10.1021/la500285m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Meißner R. H., Wei G., and Ciacchi L. C., Soft Matter 11, 6254 (2015). 10.1039/C5SM01444A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Walsh T. R. and Tomasio S. M., Mol. Biosyst. 6, 1707 (2010). 10.1039/c003417g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Benassi E., Granucci G., Persico M., and Corni S., J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 5962 (2015). 10.1021/jp511269p [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Hughes Z. E. and Walsh T. R., J. Mater. Chem. B 3, 3211 (2015). 10.1039/C5TB00004A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Wright L. B., Palafox-Hernandez J. P., Rodger P. M., Corni S., and Walsh T. R., Chem. Sci. 6, 5204 (2015). 10.1039/C5SC00399G [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Sultan A. M., Westcott Z. C., Hughes Z. E., Palafox- Hernandez J. P., Giesa T., Puddu V., Buehler M. J., Perry C. C., and Walsh T. R., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 18620 (2016). 10.1021/acsami.6b05200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ravichandran S., Madura J. D., and Talbot J., J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 3610 (2001). 10.1021/jp010223r [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zheng J., Li L., Tsao H.-K., Sheng Y.-J., Chen S., and Jiang S., Biophys. J. 89, 158 (2005). 10.1529/biophysj.105.059428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Agashe M., Raut V., Stuart S. J., and Latour R. A., Langmuir 21, 1103 (2005). 10.1021/la0478346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Shen J.-W., Wu T., Wang Q., and Pan H.-H., Biomaterials 29, 513 (2008). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Abramyan T. M., Snyder J. A., Thyparambil A. A., Stuart S. J., and Latour R. A., J. Comput. Chem. 37, 1973 (2016). 10.1002/jcc.24416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Refaee M., Tezuka T., Akasaka K., and Williamson M. P., J. Mol. Biol. 327, 857 (2003). 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00209-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Thyparambil A. A., Wei Y., and Latour R. A., Biointerphases 10, 019002 (2015). 10.1116/1.4906485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Yancey J. A., Vellore N. A., Collier G., Stuart S. J., and Latour R. A., Biointerphases 5, 85 (2010). 10.1116/1.3493470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Humphrey W., Dalke A., and Schulten K., J. Mol. Graphics 14, 33 (1996). 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. MacKerell A. D. et al. , Phys. Chem. B 102, 3586 (1998). 10.1021/jp973084f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. MacKerell A. D., Feig M., and Brooks C. L., J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1400 (2004). 10.1002/jcc.20065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Nosé S., Mol. Phys. 52, 255 (1984). 10.1080/00268978400101201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Andersen H. C., J. Comput. Phys. 52, 24 (1983). 10.1016/0021-9991(83)90014-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Frishman D. and Argos P., Proteins: Struct., Funct. Bioinformatics 23, 566 (1995). 10.1002/prot.340230412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. McGibbon R. T. et al. , Biophys. J. 109, 1528 (2015). 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.See supplementary material at http://dx.doi.org/10.1116/1.4983274 E-BJIOBN-12-328702 for Cα height of each amino-acid residue of the protein adsorbed on the HDPE surface in TIGER2A sampling (Figure S1); the justification of the choice of the optimal number of clusters in the ensemble of states obtained in the TIGER2A sampling (Figure S2); the justification of the choice of the best clustering algorithm to analyze the results of the ensembles of states obtained in TIGER2A sampling (Table S1); and the standard deviations of the clusters (Table S2).

- 97. Gower J. C., Ross G., and Roy J., Stat. Soc. C. Appl. Stat. 18, 54 (1969). 10.2307/2346439 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Defays D., Comput. J. 20, 364 (1977). 10.1093/comjnl/20.4.364 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Sokal R. R., Univ. Kans. Sci. Bull. 38, 1409 (1958). [Google Scholar]

- 100. J. H. Ward, Jr. , J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 58, 236 (1963). 10.1080/01621459.1963.10500845 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Caliński T. and Harabasz J., Commun. Stat. Theory 3, 1 (1974). 10.1080/03610927408827101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Davies D. L. and Bouldin D. W., IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. 1, 224 (1979). 10.1109/TPAMI.1979.4766909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Rousseeuw P. J., J. Comput. Appl. Math. 20, 53 (1987). 10.1016/0377-0427(87)90125-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Lindorff-Larsen K., Maragakis P., Piana S., Eastwood M. P., Dror R. O., and Shaw D. E., PloS One 7, e32131 (2012). 10.1371/journal.pone.0032131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Piana S., Klepeis J. L., and Shaw D. E., Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 24, 98 (2014). 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- See supplementary material at http://dx.doi.org/10.1116/1.4983274 E-BJIOBN-12-328702 for Cα height of each amino-acid residue of the protein adsorbed on the HDPE surface in TIGER2A sampling (Figure S1); the justification of the choice of the optimal number of clusters in the ensemble of states obtained in the TIGER2A sampling (Figure S2); the justification of the choice of the best clustering algorithm to analyze the results of the ensembles of states obtained in TIGER2A sampling (Table S1); and the standard deviations of the clusters (Table S2).