Abstract

Objectives

Insomnia is a significant public health concern known to particularly impact women and the veteran population; however, rates of insomnia disorder among women veterans are not known.

Method

Women veterans who had received health care at VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System between 2008 and 2010 and resided within 25 miles of the facility were sent a postal survey assessing sleep, demographics, and other related patient characteristics.

Results

A total of 660 women (43.1% of potential responders) returned the postal survey and provided sufficient information for insomnia diagnosis. On average, women reported 6.2 hours of sleep per night. The prevalence of insomnia, determined according to diagnostic criteria from the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-2, was 52.3%. Women with insomnia reported more severely disturbed sleep, and more pain, menopausal symptoms, stress/worries, and nightmares compared with women without insomnia. There was a quadratic relationship between age and insomnia with women in their mid-40s, most likely to have insomnia.

Conclusions

This survey study found that insomnia symptoms were endorsed by more than one-half of the women veterans in this sample of VA users, highlighting the critical need for enhanced clinical identification and intervention. Further research is needed to establish national rates of insomnia among women veterans and to improve access to evidence-based treatment of insomnia disorder.

There are 2.2 million women veterans in the United States, a number that is expected to increase to 2.4 million by 2020, based on the number of women currently serving in the armed forces (National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, 2013). Women veterans are accessing health care through the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in rapidly growing numbers. From 2000 to 2010, the number of women veterans receiving care through VHA doubled (Whitehead et al., 2013). As a result, there is an increasing call to understand this growing segment of patients served by VHA. At present, little is known regarding the prevalence of insomnia and need for sleep disorder treatment among women veterans. Yano et al. (2011) included “sleep issues” as part of the “VA Women’s Health Research Agenda for the Future”; however, as of 2011, a systematic review of VA women’s health research did not identify published studies of sleep disorders among women veterans (Bean-Mayberry et al., 2011; Goldzweig, Balekian, Rolon, Yano, & Shekelle, 2006). Since 2011, Hughes, Jouldjian, Washington, Alessi, and Martin (2013) have reported that women veterans with insomnia have higher rates of posttraumatic stress disorder, and a recent publication based on the Women’s Health Initiative reported that women veterans had similar overall rates of insomnia compared with nonveteran women (30.5% vs. 30.8%, respectively), but women veterans had higher risk for insomnia co-occurring with sleep apnea risk factors (Rissling et al., 2016). Recently, changes in rates of diagnosed sleep disorders among more than 9,000,000 VA users was described by Alexander et al. (2016). Rates of diagnosed insomnia differed between men and women who receive VA care; however, these differences were not consistent across fiscal years. Women had the same or higher rates of insomnia through fiscal 2008, and lower rates thereafter. Because multiple factors impact documented diagnosis in medical records, it is not clear whether this represents a difference in actual prevalence rates. We were unable to identify additional studies focused on sleep disorders among women veterans, and this remains an area in which research is needed.

Insomnia (defined as sleep disturbance that is sufficiently severe to cause distress or impact functioning) is a significant public health concern that contributes to lost productivity, psychological distress, poor quality of life, poor health, medical morbidity, and mortality risk (Godet-Cayre et al., 2006; Katz & McHorney, 2002; Kripke, Garfinkel, Wingard, Klauber, & Marler, 2002; Zammit, Weiner, Damato, Sillup, & McMillan, 1999). A Canadian study showed that direct and indirect costs for individuals with insomnia exceeds costs for good sleepers by 10-fold (Daley, Morin, Leblanc, Gregoire, & Savard, 2009). Importantly, treatment of insomnia improves quality of life and may reduce depression and pain symptoms as well (Edinger, Wohlgemuth, Krystal, & Rice, 2005; Manber et al., 2008; Vitiello, Rybarczyk, VonKorff, & Stepanski, 2009). In fact, the VA has invested resources in training mental health providers in the treatment of insomnia disorder through a national dissemination of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (Manber et al., 2012; Trockel, Karlin, Taylor, & Manber, 2014).

Insomnia prevalence among women veterans has not been widely studied; however, there are reasons to suspect it will be more common among women veterans than among male veterans. Estimated rates of insomnia among male veterans vary from 24% to 54% (Hoge et al., 2008), but similar estimates are not available for women veterans. Among nonveterans, insomnia is more common among women than men, with a mean prevalence of 23% among U.S. civilian women compared with 17% among men (National Sleep Foundation, 2007; Zhang & Wing, 2006). A meta-analytic review found that women are 1.4 times more likely to have insomnia than men, worldwide (Zhang & Wing, 2006). In light of the sex and gender differences that may contribute to high risk for sleep difficulties among women, a recent report highlighted the need to examine women’s sleep health issues (Mallampalli & Carter, 2014).

Risk factors for insomnia include psychiatric disorders, medical conditions, psychosocial stressors, and sleep disorders (e.g., sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome; Martin, 2005). These conditions are not exclusive to women; however, women do suffer from higher rates of some psychiatric disorders known to contribute to insomnia (e.g., depression), and insomnia complaints increase significantly during pregnancy (Dorheim, Bjorvatn, & Eberhard-Gran, 2012), and as women enter menopause (Eichling & Sahni, 2005).

The objectives of the current study were to characterize patient-reported sleep, estimate the prevalence of insomnia, and identify common sleep-disruptive factors among women veterans who receive VA health care. A secondary objective was to identify differences between women with and without insomnia in terms of demographics and other characteristics assessed in the postal survey used in the study. Based on prior research, we hypothesized that the prevalence of insomnia would be at least as high among women veterans in this study as it is in the general population, and that women with insomnia would be older and would endorse more sleep-disruptive factors than women without insomnia.

Materials and Methods

Study Sample and Recruitment

The sample for the current study was drawn from the population of women veterans who received care at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System between 2008 and 2010 and resided within 25 miles of the VA Sepulveda Ambulatory Care Center, where the study was conducted (N = 1,632). The list of eligible women was put into random order, and approximately 500 surveys were mailed at 4-month intervals between August 2010 and August 2011 until all 1,632 women had been sent a survey. These steps were taken to reduce the risk of a “seasonal response bias” (Halbesleben & Whitman, 2012). If we did not receive a returned survey within 3 weeks, a second survey was mailed. This step was taken both to increase response rate and to reduce potential nonresponse bias (Halbesleben & Whitman, 2012). Of the 1,632 mailed surveys, 102 were not delivered (3 because the veteran was deceased, and 98 because the veteran did not reside at the address listed and no forwarding address was available). This formed a pool of 1,530 potential responders. Of these, 671 (43.9%) returned a survey, 499 (74.4%) after the first mailing and 172 (25.6%) after the second mailing. The 671 returned surveys were examined for completeness, and we attempted to contact respondents with missing or ambiguous responses, yielding 69 additional completed and corrected surveys. There was sufficient information to determine whether the veteran met criteria for insomnia disorder for a final sample of 660 women (43.1% of potential responders). The study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and a waiver of documentation of informed consent was obtained.

Survey Content

The survey was developed for the purpose of identifying women veterans with insomnia complaints who were likely to meet clinical diagnostic criteria for an insomnia disorder, according to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd Edition (ICSD-2; American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2005). The survey included cover material describing the survey as research and a total of 37 items, which are described in detail herein.

Demographics

Demographic, military-related, and health care use variables included in the current study were age, sex, race/ethnicity, employment status, marital status, period of military service, time since last medical visit (within 2 years), and distance from the medical center. Age, sex, time since last medical visit, and distance from the medical center were obtained from the administrative database so this information was not asked on the survey; however, a majority of individuals had missing information about race/ethnicity in the administrative database, so this demographic variable was included in the survey in addition to employment status and marital status (which were not available in the administrative dataset).

Insomnia

To identify women with insomnia, we applied an algorithm addressing each of the diagnostic criteria for insomnia disorder in the ICSD-2 (American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2005). The survey included multiple items targeting each criterion so one missing item would not prevent the survey from being useable (20 items total). Table 1 shows the diagnostic criteria (column 1) and how the criteria were operationalized within the survey (column 2). We also assessed duration of insomnia (listed as criteria D), focusing on individuals who had experienced insomnia for 3 months or more, consistent with the research diagnostic criteria for insomnia disorder (Edinger, Bonnet, & Bootzin, 2004).

Table 1.

Method for Identifying Individuals with an Insomnia Disorder Based on ICSD-2 Criteria

| ICSD-2 Insomnia Criteria | Operational Definition |

|---|---|

| Criterion A: Difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, waking too early in the morning, or sleep that is nonrestorative or poor in quality | Met if respondent reported >30 minutes to fall asleep or trouble falling asleep, staying asleep or waking too early or sleep efficiency (time asleep/time in bed) <80% or sleep quality was rated as fairly bad or very bad. |

| Criterion B: Sleep disturbance occurs despite adequate opportunity and circumstances | Reports a comfortable place to sleep and spends ≥5 hours in bed. |

| Criterion C: One or more daytime impairments related to sleep difficulty including: 1) fatigue or malaise, 2) attention, concentration or memory impairment, 3) social or vocational dysfunction, 4) mood disturbance or irritability, 5) daytime sleepiness, 6) motivation, energy or initiative reduction, 7) proneness to errors or accidents, 8) tension, headaches or gastrointestinal symptoms in response to sleep loss, 9) concerns or worries about sleep | Respondent endorses any of the following symptoms: 1) tired or fatigued, 2) trouble paying attention, 3) difficulty with work, 4) irritable, depressed, anxious, 5) sleepy during the day, 6) less motivation, energy, or drive, 7) making mistakes, 8) having accidents, 9) feeling achy, having headaches, or stomach problems, 10) worry about sleep, 11) taking a nap or dozing off during the daytime. |

| Criterion D*: Persistence of sleep problems. | Respondent had sleep problems for 3 months or longer. |

Abbreviation: ICSD,2, International Classification of Sleep Disorders–Revised.

Criterion D was derived from the research diagnostic criteria for insomnia (Edinger et al., 2004).

General view of sleep and attempts to address sleep problems

Women were asked, “In general, how would you describe your sleep during the past month?” rated on a 4-point scale (from very good to very bad) using the sleep quality item from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989). They were also asked whether they had made attempts to address sleep problems, including talking to a doctor, or taking prescription or over-the-counter sleep medications in the past month (all yes/no).

General health

Given the potential impact of insomnia on quality of life, the general health item from the Short Form-36 (i.e., “In general, how would you rate your current health?” with response options on a five-point scale from excellent to poor) was also included to describe respondents’ self-perceived overall health status (Leger, Scheuermaier, Philip, Paillard, & Guilleminault, 2001).

Sleep disruptive factors

In consideration of factors common to insomnia patients, seven items were used to assess conditions known to possess the potential for disrupting sleep in the past month. Items included pain, pregnancy, menopause symptoms, taking care of children/other household members at night, working at night, stress, and nightmares (all yes/no).

Data Analysis

Before analysis, the distribution of responses for each survey item was examined. There were low rates of missing responses per item (range, 0.2%–2.4% missing); therefore, we did not evaluate nonresponse bias at the item level. Response bias was evaluated only at the survey level (described below).

Hypothesis testing

For each analysis, two-sided testing was performed with an alpha of 0.05. Analyses were conducted using Stata/MP version 13.1 (StataCorp, 2013). Insomnia diagnoses were established using the criteria described above. Rates of insomnia were computed for the sample using the tabulate command and population estimates were computed using the sampling weight (i.e., pweight) in conjunction with the svy prefix and tabulate command. Other tabulations for the sample were also computed using the tabulate command, and summary statistics (e.g., means and standard deviations) for the sample were computed using the summarize command within the Stata software. Comparisons between women with and without insomnia were performed using t tests (for continuous outcomes) and Fisher’s exact tests (for binary and categorical outcomes). Analyses examining the relationship between age and the diagnosis of insomnia were computed using the logistic command combined with the svy prefix to provide estimates adjusted for the sample weights. A squared term for age was added to the model to test for (and account for) a quadratic relationship between age and the presence of insomnia.

Sensitivity analysis of insomnia prevalence

We investigated the degree to which insomnia rates were sensitive to more stringent application of criterion A (sleep disturbance) and criterion C (daytime consequences). Four variations were applied: 1) requiring two of the six components of poor sleep to be endorsed for criterion A; 2) requiring two daytime consequences to be endorsed for criterion C; 3) omitting each component of criterion A (one at a time), and 4) omitting each component of criterion C (one at a time). We also examined differences in rates of insomnia based on duration of symptoms (criterion D). This approach tested the potential impact of variations in the definition of insomnia on the observed rates of insomnia in this study.

Results

Survey responders (n = 660) had a mean age of 50.9 years (SD, 17.7; range, 22–98), 49.4% were White/Caucasian, 30.1% African American, 17.4% Hispanic/Latina, 6% Asian/Asian American, 3.5% American Indian/Alaskan Native, 0.8% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and 3.4% other. The largest percentage of respondents (n = 237, 36.2%) reported working for wages; however, a majority reported they did not work for wages (16.1% unable to work, 19.0% unemployed, 23.5% retired, 16.2% student, 5.5% homemaker). Regarding marital status, 22.9% said they were married or living as married, 32.7% reporting being divorced, 4.6% separated, 9.2% widowed, and 30.7% said they have never been married. Approximately 85% reported serving in the military during a time of war or conflict (i.e., World War II, Korean War, Vietnam War, Persian Gulf War, or Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom).

Survey Response Rate and Nonresponse Weighting

The overall response rate was 43.1% (n = 660 returned, completed surveys). Responders were significantly older than nonresponders (mean age = 50.9 vs. 48.3 years, respectively; t1528 = −2.84; p = .005) and their last VA visit was significantly more recent (mean months since last visit, 4.1 vs. 4.4, respectively; t1528 = 2.26; p = .024). There was no difference in distance from the medical center, which was the only other variable available for comparisons. Age and time since last visit were used to create nonresponse weights, which were included in computation of population prevalence estimates (Groves, Dillman, Eltinge, & Little, 2001).

Characteristics of Sleep among Women Veterans

Overall,13.7% of women reported sleep quality as “very good,” 44.2% as “fairly good,” 34.8% as “fairly bad” and 7.4% as “very bad.” On average, women went to bed at 11:02 PM (SD, 1.46 hours) and arose at 6:59 AM (SD, 2.06 hours), spending an average of 8.0 hours (SD, 1.8 hours) in bed. Women reported an average of 6.2 (SD, 1.8) hours of sleep per night, for a calculated sleep efficiency of 79.4% (SD, 18.1%). In terms of types of sleep difficulties, women most commonly reported difficulty staying asleep (67.5%). Complaints of trouble falling asleep (52.1%) and early morning awakenings (62.0%) were also common. There was overlap in these symptoms, with 38.5% (N = 252) reporting all three, 24.6% (N = 161) reporting two of the three, and 16.4 % (N = 107) reporting only one of these problems. Overall, 79.5% of women reported at least one sleep complaint.

In terms of duration of sleep problems, 57.1% reported having sleep problems lasting more than 12 months; 10.8% reported sleep problems lasting 3 to 12 months; 5.8% reported sleep problems lasting less than 3 months, and 26.2% reported not having sleep problems.

Prevalence of Insomnia among Women Veterans

Using the criteria described in Table 1 to identify insomnia, 84.8% (n = 560) reported sleep disturbance (criterion A), of whom 81.6% (n = 457) indicated adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep (criterion B). Among women meeting both criteria A and B, 95.0% (n = 434) reported one or more daytime consequences poor sleep. Among the 434 women who met criteria A, B and C, 79.5% (n = 345) indicated that their sleep difficulties had persisted for 3 months or longer. Thus, out of 660 survey respondents, 345 met our operational definition for insomnia disorder, yielding an unadjusted overall rate of 52.3% with insomnia. When we applied nonresponse weights (accounting for age and time since last visit), the adjusted rate was 52.6% (95% confidence interval [CI], 48.8%–56.4%) with insomnia.

Sensitivity analysis of insomnia prevalence

To evaluate the potential impact of variations in the definition of insomnia on observed rates of insomnia, we tested multiple more stringent definitions (described above). Requiring an individual to endorse two aspects of sleep disturbance under criterion A lowered the estimated prevalence of insomnia by the greatest degree, to 50.0% (95% CI, 46.2%–53.9%). Requiring endorsement of two (or more) daytime consequences (criterion C) yielded a trivial change in the estimated prevalence (52.2%; 95% CI, 48.3%–56.0%). The estimated prevalence was very consistent when removing one of each of the components of criterion A or criterion C, changing the estimates by less than 2%. When we examined insomnia complaints lasting at least 1 year, the insomnia prevalence was 44.0% (95% CI, 40.2%–47.8%), and there were an additional 4.4% (95% CI, 3.0%–6.3%) who reported acute insomnia for less than 3 months.

Comparison of Women with and without Insomnia

Table 2 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of women with and without insomnia according to the prespecified criteria described above. Women who met the criteria for insomnia were younger, but no differences were observed in race/ethnicity, employment status, or marital status between those who met criteria for insomnia and those who did not.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Women Veterans with and without Insomnia in One Veterans Administration Health Care System

| With Insomnia (n = 345) | Without Insomnia (n = 315) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years, M (SD) | 49.10 (15.8%) | 52.90 (19.3%) |

| Race/ethnicity (n = 654), n (%) | ||

| African American | 102 (29.7) | 95 (30.6) |

| Hispanic/Latina | 63 (18.4) | 51 (16.4) |

| White/Caucasian | 169 (49.3) | 154 (49.5) |

| Asian or Asian American | 20 (5.8) | 19 (6.1) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (.3) | 4 (1.3) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 13 (3.8) | 10 (3.2) |

| Other | 14 (4.1) | 8 (2.6) |

| Employment status (n = 654), n (%) | ||

| Employed for wages | 129 (37.4) | 108 (35.0) |

| Unable to work | 66 (19.1) | 39 (12.6) |

| Unemployed | 72 (20.9) | 52 (16.8) |

| Retired | 65 (18.8) | 89 (28.8) |

| Student | 55 (15.9) | 51 (16.5) |

| Homemaker | 20 (5.8) | 16 (5.2) |

| Marital status (n = 654), n (%) | ||

| Married or living as married | 83 (24.1) | 67 (21.6) |

| Divorced | 115 (33.4) | 99 (31.9) |

| Separated | 16 (4.7) | 14 (4.5) |

| Widowed | 27 (7.9) | 33 (10.7) |

| Never married | 104 (30.2) | 97 (31.3) |

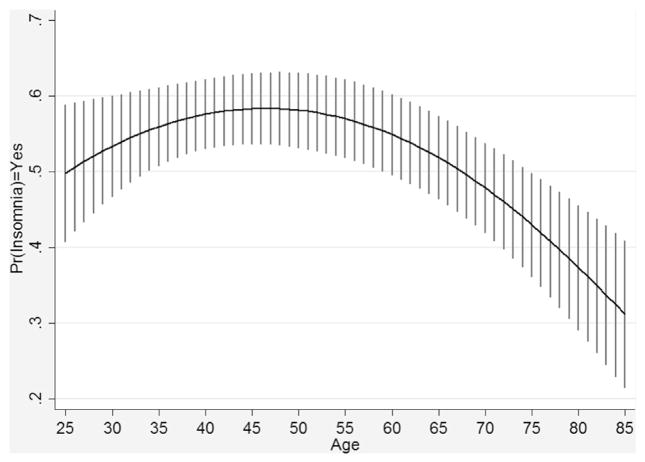

To further investigate our specific hypotheses about age and insomnia, we used a logistic regression analysis in which insomnia was predicted from age as well as age-squared (to account for a possible nonlinear quadratic relationship between age and probability of insomnia). The overall model was significant (N = 660; p < .001) as was the quadratic effect of age (p = .001; Figure 1). The estimated prevalence of insomnia at age 25 was 49.8% (95% CI, 40.7%–58.8%), a rate that increased until age 46, at which point the rate reached its maximum of 58.3% (95% CI, 53.6–63.0%), and then decreased across subsequent ages.

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of insomnia as a function of age (and age squared) with 95% confidence intervals. The peak probability of insomnia occurred at age 46 with the lowest rates among women in the later years of life.

Women with insomnia reported taking significantly longer to fall asleep, indicated higher rates of attempts to address sleep problems, and had higher rates of sleep disturbance from pain, menopause symptoms, stress or worries, and nightmares, and rated their sleep as significantly worse in quality compared with women without insomnia (Table 3). Compared with women without insomnia, women veterans with insomnia also reported higher rates of all daytime consequences of poor sleep queried in the survey.

Table 3.

Rating of General Health, Endorsement of Attempts to Address Sleep Problems and of the Occurrence of Common Sleep Disruptive Factors in the Past Month among Women Veterans in One VA Health Care System (n = 660)

| Survey Items, n (%) | With Insomnia (n = 345) | Without Insomnia (n = 315) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| General health | |||

| Poor | 18 (5.2) | 19 (6.1) | <.001 |

| Fair | 101 (29.4) | 57 (18.3) | |

| Good | 145 (42.2) | 107 (34.3) | |

| Very good | 68 (19.8) | 90 (28.9) | |

| Excellent | 12 (3.49) | 39 (12.5) | |

| Attempts to address sleep problems | |||

| Talked to a doctor about sleep problems | 230 (66.9) | 84 (26.7) | <.001 |

| Prescription med for sleep in past month | 133 (38.6) | 58 (18.5) | <.001 |

| Over-the-counter med for sleep in past month | 68 (19.7) | 29 (9.3) | <.001 |

| Causes of sleep problems in the past month | |||

| Pain | 215 (62.7) | 116 (36.9) | <.001 |

| Pregnancy | 6 (1.8) | 5 (1.6) | .999 |

| Menopause symptoms | 84 (24.6) | 41 (13.1) | <.001 |

| Taking care of kids/other people at night | 49 (14.4) | 32 (10.2) | .122 |

| Working at night | 24 (7.0) | 25 (8.0) | .659 |

| Stress or worries | 286 (83.1) | 165 (52.7) | <.001 |

| Nightmares | 160 (46.6) | 77 (24.6) | <.001 |

| Self-reported sleep quality | |||

| Very bad | 32 (9.3) | 17 (5.4) | <.001 |

| Fairly bad | 174 (50.4) | 55 (17.5) | |

| Fairly good | 137 (39.7) | 154 (49.0) | |

| Very good | 2 (0.6) | 88 (28.0) | |

| Type of sleep disturbance | |||

| Trouble falling asleep | 250 (72.5) | 92 (29.6) | <.001 |

| Trouble staying asleep | 312 (90.4) | 132 (42.2) | <.001 |

Discussion

This study provides an epidemiological glimpse at insomnia among women veterans who receive VA health care. Through a postal survey design to assess the presence of symptoms of a likely clinical insomnia disorder (based on ICSD-2 criteria), we found that insomnia is highly prevalent (53% adjusted rate), particularly compared with previous studies of insomnia in nonveteran women in the United States, which estimated rates of approximately 23% in the United States (Roth et al., 2011; Zhang & Wing, 2006). Epidemiological studies to evaluate insomnia prevalence among nonveteran U.S. women have used insomnia rating scales with clinical cutoffs (Alcantara et al., 2016) or other brief evaluation of symptoms (Ford, Cunningham, Giles, & Croft, 2015). We also found that women veterans with insomnia differed from those without insomnia in terms of age and other sleep disruptive factors including pain, menopause symptoms, stress or worries, and nightmares.

To confirm the validity of our estimate, we applied more stringent criteria for assessing insomnia, yet the prevalence of insomnia dropped by no more than 2%. Furthermore, we found that 44% of respondents meeting the other criteria for insomnia had sleep difficulties for more than 1 year, which is still higher than the rates of all insomnia (approximately 23%) in the general population of U.S. women (Roth et al., 2011; Zhang & Wing, 2006). These high rates of chronic insomnia are likely related to elevated rates of long-standing posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, chronic pain, and other comorbidities experienced by women veterans (Washington, Davis, Der-Martirosian, & Yano, 2013).

More generally, our findings confirm high rates of sleep disturbance among women veterans, with a significant number endorsing poor overall sleep quality, and two-thirds indicating difficulty maintaining sleep at night. A small but clinically significant portion of women without insomnia rated their sleep quality as “very bad” (5.4%) or “fairly bad” (17.5%). This may be accounted for by sleep disorders other than insomnia. Women reported an average nightly sleep duration of only 6 hours, echoing a previous epidemiologic study in which 45% of women veterans surveyed reported getting fewer than 7 hours of sleep per night (Seelig et al., 2012). A majority of women in our study reported trouble falling sleep, trouble staying asleep, and trouble with early awakenings, showing all types of sleep difficulties are likely to occur in women veterans treated within VA. Importantly, the recommended number of hours of sleep per night for adults is 7 or more hours (Consensus Conference Panel et al., 2015; Watson et al., 2015), and insufficient sleep, whether owing to insomnia or other sleep-related difficulties, is a significant problem worthy of further exploration.

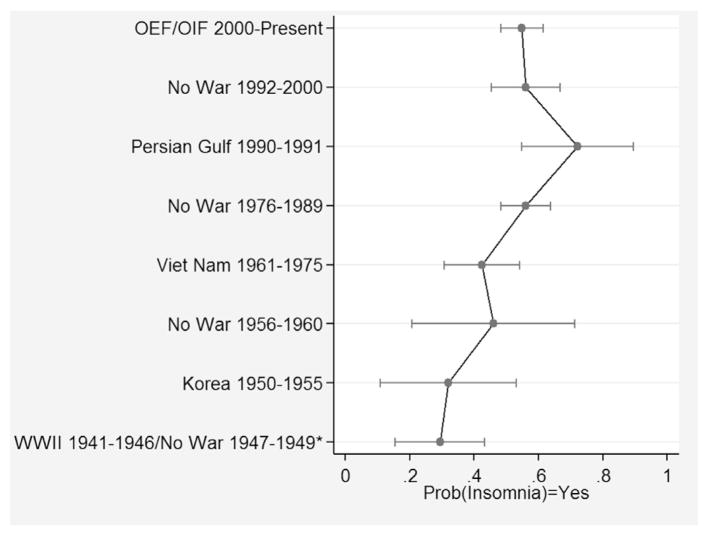

We were also interested in differences in insomnia rates across sociodemographic groups, particularly across age groups, which overlaps with the period of time women served in the armed forces (Washington, Bean-Mayberry, Hamilton, Cordasco, & Yano, 2013). Because there have not been periods of compulsory military service for women (i.e., women have never been “required” to serve owing to a draft), we expected less pronounced differences across periods of service compared with differences across age groups. We elected to explore age as a predictor of insomnia, rather than period of service, and interestingly, the relationship between age and insomnia rate was nonlinear. The youngest and oldest women were least likely to meet criteria for insomnia. Based on earlier studies suggested rates of insomnia increase with age (Mellinger, Balter, & Uhlenhuth, 1985), we tested nonlinear trends in insomnia rates by age; however, our findings are more consistent with recent studies showing that rates of sleep disruption are no longer highest in the oldest age groups (Grandner et al., 2012). Owing to the cross-sectional nature of our survey, it is not clear whether this pattern of insomnia prevalence across ages represents a cohort effect (i.e., women in this age cohort are more likely to complain of poor sleep), or whether other factors at midlife account for this effect. Such factors might include family and occupational stressors, caregiving responsibilities, onset of menopausal symptoms, and other unmeasured health conditions that emerge at midlife. Other demographic characteristics (race/ethnicity, marital status, and employment status) did not differ between women who endorsed insomnia symptoms and those who did not. To follow up on this finding, when period of service was used instead of age, we found that the patterns fully overlapped, and women who served during the Persian Gulf War (1990–1991) had the highest rates of insomnia (Figure 2). This finding may be potentially important because about one-quarter of veterans who served in the first Persian Gulf War suffer from “Gulf War Illness,” which consists of bodily pain, mood and cognitive disturbances, fatigue, poor sleep quality, and insomnia. Although we did not specifically inquire about Gulf War Illness symptomatology, increased rates of insomnia in this cohort may be partly explained by that condition (Smith et al., 2013).

Figure 2.

Predicted probability of insomnia as a function of period of service cohort. The peak probability of insomnia was among women who served during the Persian Gulf War, and the lowest rates were observed for women who served in World War II (WWI) or during peacetime before the Korean War. Abbreviation: OEF/OIF, Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Strengths and Limitations

A key strength of our study was the ability to distribute the postal survey to the entire population of women meeting the inclusion criteria. We used multiple methods to enhance survey response and reduce nonresponse bias (Halbesleben & Whitman, 2012). We also included cover materials designed to increase interest in the topic, noting that we were interested in learning from women who slept well in addition to those with insomnia. A limitation of our study is that the response rate obtained (43%) makes potential nonresponse bias a concern, and there were some small differences between responders and nonresponders that necessitated statistical adjustments for nonresponse, yet when we included nonresponse weights, the estimated prevalence of insomnia was minimally impacted. Studies show that response rates to postal surveys are declining nationwide. A 2001 study evaluating pregnancy had a response rate of 49% to 84% across states (Shulman, Gilbert, Msphbrenda, & Lansky, 2006), and a survey of eating disorders behavior had a response rate of 52.9% (Mond, Rodgers, Hay, Owen, & Beumont, 2004). These studies suggest that our survey response rate was not unexpectedly low. Another limitation of our study is generalizability; it is unclear whether findings from this study are specific to the geographic region in which the study was conducted. Future studies should consider multiple sources of data and assess a national sample of women veterans so the scope of this problem on a national level can be assessed and resources can be appropriately allocated. A final limitation of our survey methodology was that we could not assess the co-occurrence of other sleep disorders, such as sleep apnea, which is diagnosed with an overnight sleep recording such as home sleep apnea testing or in-laboratory polysomnography. Sleep apnea would suggest a different approach to treatment is required above and beyond what is needed to treat insomnia disorders (e.g., access to a sleep disorders clinic). Given findings that sleep apnea risk factors and insomnia co-occur more frequently in women veterans than in nonveteran women (Rissling et al., 2016), future studies should explore co-occurring sleep disorders, including sleep apnea, among women veterans. We also did not assess subtypes of insomnia such as insomnia owing to a medical disorder, idiopathic insomnia, or psychophysiological insomnia. It remains unclear whether this level of detail can be assessed with a postal survey alone.

Conclusions

We found that more than one-half of women who receive care at the VA Greater Los Angeles met criteria for insomnia disorder, with the highest rates among midlife women. We also found that these sleep complaints are complex, including trouble falling and staying asleep and short sleep duration, and that insomnia is often very chronic. Those with insomnia were older and experienced sleep disruption owing to pain, menopause symptoms, stress or worries, and nightmares. Given how common insomnia disorder seems to be, access to evidence-based insomnia treatments are needed.

Implications for Practice and/or Policy

Our study provides initial evidence that insomnia symptoms are a frequent concern among women veterans. Although estimates of the national prevalence of insomnia among women veterans, both VA and non-VA users, is needed, it is clear that treatment for insomnia is an ongoing and potentially growing concern, as women in active duty status end their military service and enter the veteran population. Efforts to disseminate evidence-based treatment of insomnia within VA (Karlin & Cross, 2014; Manber et al., 2012) may not be sufficient to address the scope of the problem among women veterans, and additional resources may be required. For example, specifically targeting mental health providers who work primarily with women veterans and providing additional support and consultation may be useful. Alternative delivery models, such as telehealth and brief behavioral approaches, may also increase access for women with milder forms of insomnia who do not necessarily require highly specialized and individualized care. At our VA facility, we have a comprehensive insomnia treatment program within our sleep disorders center; however, in 2010 when women represented 8% of the total number of patients served by our medical center, only 4% of the total number of patients referred for insomnia treatment were women (unpublished data). The current study suggests women currently in midlife, who represent the largest age group of women veteran VA users (Frayne et al., 2016), may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of sleep disturbance and in need of identification and treatment facilitation. Future studies also need to evaluate access barriers to women taking advantage of available insomnia treatment programs within VA and to identify possible facilitators to accessing available sleep-related services, including treatment for insomnia.

Acknowledgments

Research supported: VA Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D; PPO 09-282-1; PI: Martin), VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI; RRP 12–189; PI: Martin), and Research Services of the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. Dr. Schweizer was supported by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations through the VA Advanced Fellowship Program in Women’s Health.

Additional acknowledgments

The authors thank Julia Yosef, MA, RN, Simone Vukelich, and Sergio Martinez for their assistance with the study. We wish to posthumously thank Terry Vandenberg, MA, for her many contributions to this project as well.

Biographies

Jennifer L. Martin, PhD, is at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center and David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles. Her research interests are sleep disorders, aging, and women veteran’s health.

C. Amanda Schweizer, PhD, MPH, is at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, HSR&D Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation, Implementation & Policy. Her research interests are substance use disorders and women’s health.

Jaime M. Hughes, PhD, MPH, MSW, is at Durham VA Healthcare System, Center for Health Services Research in Primary Care, Durham, NC. Her research interests are aging and sleep.

Constance H. Fung, MD, MSHS, is at VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center and the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her research interests are aging and sleep.

Joseph M. Dzierzewski, PhD, is at Virginia Commonwealth University, Department of Psychology, Richmond VA. His research interests are aging, sleep and cognition.

Donna L. Washington, MD, MPH, is Professor of Medicine at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine. She is a general internist whose research focuses on health care access and quality for women and racial/ethnic minorities.

B. Josea Kramer, PhD, is at VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center and the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her research interests are veteran health care and aging.

Stella Jouldjian, MSW, MPH, is at VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center. Her research interests are aging, sleep and women veteran’s health.

Michael N. Mitchell, PhD, is at VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center. He is the study statistician.

Karen R. Josephson, MPH, is at VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center. Her research interests are aging and sleep.

Cathy A. Alessi, MD, is at VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center and the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her research interests are aging and sleep.

References

- Alcantara C, Biggs ML, Davidson KW, Delaney JA, Jackson CL, Zee PC, … Redline S. Sleep disturbances and depression in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Sleep. 2016;39:915–925. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander M, Ray MA, Hebert JR, Youngstedt SD, Zhang H, Steck SE, … Burch JB. The National Veteran Sleep Disorder Study: Descriptive epidemiology and secular trends, 2000–2010. Sleep. 2016;39:1399–1410. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The international classification of sleep disorders. 2. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. I. Insomnia; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bean-Mayberry B, Yano EM, Washington DL, Goldzweig C, Batuman F, Huang C, … Shekelle PG. Systematic review of women veterans’ health: Update on successes and gaps. Women’s Health Issues. 2011;21:S84–S97. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consensus Conference Panel. Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, Bliwise DL, Buxton OM, … Tasali E. Joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: Methodology and discussion. Sleep. 2015;38:1161–1183. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley M, Morin CM, Leblanc M, Gregoire JP, Savard J. The economic burden of insomnia: Direct and indirect costs for individuals with insomnia syndrome, insomnia symptoms, and good sleepers. Sleep. 2009;32:55–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorheim SK, Bjorvatn B, Eberhard-Gran M. Insomnia and depressive symptoms in late pregnancy: A population-based study. Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 2012;10:152–166. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2012.660588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edinger JD, Bonnet MH, Bootzin RR. Derivation of research diagnostic criteria for insomnia: Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine work group. Sleep. 2004;27:1567–1596. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edinger JD, Wohlgemuth WK, Krystal AD, Rice JR. Behavioral insomnia therapy for fibromyalgia patients: A randomized clinical trial. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165:2527–2535. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.21.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichling PS, Sahni J. Menopause related sleep disorders. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2005;1:291–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ES, Cunningham TJ, Giles WH, Croft JB. Trends in insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness among U.S. adults from 2002 to 2012. Sleep Medicine. 2015;16:372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frayne SM, Phibbs CS, Saechao F, Maisel NC, Friedman SA, Finlay A, … Iqbal S. Women Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Volume 3. Sociodemographics, Utilization, Costs of Care, and Health Profile. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Godet-Cayre V, Pelletier-Fleury N, Le Vaillant M, Dinet J, Massuel M, Leger D. Insomnia and absenteeism at work. Who pays the cost? Sleep. 2006:29. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldzweig CL, Balekian TM, Rolon C, Yano EM, Shekelle PG. The state of women veterans’ health research. Results of a systematic literature review. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:S82–S92. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00380.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandner MA, Martin JL, Patel NP, Jackson NJ, Gehrman PR, Pien GW, et al. Age and sleep disturbances among American men and women: Data from the U.S. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Sleep. 2012;35:395–406. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves RM, Dillman DA, Eltinge JL, Little RJA. Survey nonresponse. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben JRB, Whitman MV. Evaluating survey quality in health services research: a decision framework for assessing nonresponse bias. Health Services Research. 2012 doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, McGurk D, Thomas JL, Cox AL, Engel CC, Castro CA. Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. Soldiers returning from Iraq. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358:453–463. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JM, Jouldjian S, Washington DL, Alessi CA, Martin JL. Insomnia and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder among women Veterans. Journal of Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 2013;11:258–274. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2012.683903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin BE, Cross G. From the laboratory to the therapy room: National dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychotherapies in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care System. American Psychologist. 2014;69:19–33. doi: 10.1037/a0033888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz DA, McHorney CA. The relationship between insomnia and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic illness. Journal of Family Practice. 2002;51:229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, Klauber MR, Marler M. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:131–136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leger D, Scheuermaier K, Philip P, Paillard M, Guilleminault C. SF-36: evaluation of quality of life in severe and mild insomniacs compared with good sleepers. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2001;63:49–55. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200101000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallampalli MP, Carter CL. Exploring sex and gender differences in sleep health: A society for Women’s Health Research report. Journal of Women’s Health. 2014;23:553–562. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manber R, Carney C, Edinger J, Epstein D, Friedman L, Haynes PL, et al. Dissemination of CBTI to the non-sleep specialist: Protocol development and training issues. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2012;8:209–218. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manber R, Edinger JD, Gress JL, San Pedro-Salcedo MG, Kuo TF, Kalista T. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia enhances depression outcome in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and insomnia. Sleep. 2008;31:489–495. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JL. Insomnia: Diagnosis and treatment. Clinical Geriatrics. 2005;12:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mellinger GD, Balter MB, Uhlenhuth EH. Insomnia and its treatment. Prevalence and correlates. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985;42:225–232. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790260019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond JM, Rodgers B, Hay PJ, Owen C, Beumont PJ. Mode of delivery, but not questionnaire length, affected response in an epidemiological study of eating-disordered behavior. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2004;57:1167–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. [Accessed: May 13, 2013];National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics: Veteran Population. 2013 Available: www.va.gov/VETDATA/Veteran_Population.asp.

- National Sleep Foundation. National Sleep Foundation: Sleep in America poll 2007 (Rep. No. 06–897) Washington, DC: Author; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rissling MB, Gray KE, Ulmer CS, Martin JL, Zaslavsky O, Gray SL, … Weitlauf JC. Sleep disturbance, diabetes and cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal veteran women. Gerontologist. 2016;56:S54–S66. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth T, Coulouvrat C, Hajak G, Lakoma MD, Sampson NA, Shahly V, … Kessler RC. Prevalence and perceived health associated with insomnia based on DSM-IV-TR; International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision; and Research Diagnostic Criteria/International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Second Edition criteria: results from the American Insomnia Survey. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;69:592–600. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seelig AD, Jacobson IG, Smith B, Hooper TI, Gackstetter GD, Ryan MA, … Smith TC Millennium Cohort Study Team. Prospective evaluation of mental health and deployment experience among women in the US military. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2012;176:135–145. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman HB, Gilbert BC, Msphbrenda CG, Lansky A. The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): Current methods and evaluation of 2001 response rate. Public Health Reports. 2006;121:74–83. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BN, Wang JM, Vogt D, Vickers K, King DW, King LA. Gulf war illness: Symptomatology among veterans 10 years after deployment. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2013;55:104–110. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318270d709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata statistical software: Release 13.1 (version 13.1) [Computer software] College Station, TX: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Trockel M, Karlin BE, Taylor CB, Manber R. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for insomnia with veterans: Evaluation of effectiveness and correlates of treatment outcomes. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2014;53:46. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello MV, Rybarczyk B, VonKorff M, Stepanski EJ. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia improves sleep and decreases pain in older adults with co-morbid insomnia and osteoarthritis. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2009;5:355–362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington DL, Bean-Mayberry B, Hamilton AB, Cordasco KM, Yano EM. Health profiles of U.S. women veterans by war cohort: Findings from the National Survey of Women Veterans. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013;28:S571–S576. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2323-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington DL, Davis TD, Der-Martirosian C, Yano EM. PTSD risk and mental health care engagement in a multi-war era community sample of women veterans. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013;28:894–900. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2303-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, Bliwise DL, Buxton OM, Buysse DJ, … Tasali E. Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: A joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Sleep. 2015;38:843–844. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead AM, Davis MB, Duvernoy C, Safdar B, Nkonde-Price C, Iqbal S, … Haskell SG. The State of Cardiovascular Health in Women Veterans. Volume I: VA Outpatient Diagnoses and Procedures in Fiscal Year (FY) 2010. Washington, D.C: Women’s Health Evaluation Initiative, Women’s Health Services, Veterans Health Administration Department of Veterans Affairs; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yano EM, Bastian LA, Bean-Mayberry B, Eisen S, Frayne S, Hayes P, … Washington DL. Using research to transform care for women Veterans: Advancing the research agenda and enhancing research-clinical partnerships. Women’s Health Issues. 2011;21:S73–S83. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zammit GK, Weiner J, Damato N, Sillup GP, McMillan CA. Quality of life in people with insomnia. Sleep. 1999;22:S379–S385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Wing YK. Sex differences in insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep. 2006;29:85–93. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]